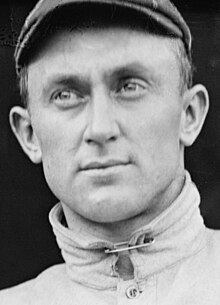

Ty Cobb

| Ty Cobb | |

|---|---|

| |

| Outfielder | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| debut | |

| August 30, 1905, for the Detroit Tigers | |

| Last appearance | |

| September 11, 1928, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| Career statistics | |

| Batting average | .366 |

| Hits | 4189 |

| Home runs | 117 |

| RBIs | 1,939 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

|

As player As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| [[{{{hoflink}}}|Member of the {{{hoftype}}}]] | |

| Induction | 1936 |

| Vote | 98.2% |

Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb (December 18, 1886 – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "The Georgia Peach," was an American outfielder in baseball born in Narrows, Georgia.[1] Cobb spent 22 seasons with the Detroit Tigers, the last six as the team's player-manager, and finished his career with the Philadelphia Athletics.

Cobb is widely regarded as one of the best players of all time.[2][3] In 1936, Cobb received the most votes of any player on the inaugural Baseball Hall of Fame ballot,[4] receiving 222 out of a possible 226 votes.

Cobb is widely credited with setting 90 Major League Baseball records during his career.[5][6][7][8] He still holds several records as of 2010, including the highest career batting average (.366) and most career batting titles with 11 (or 12, depending on source).[9] He retained many other records for almost a half century or more, including most career hits until 1985 (4,189 or 4,191, depending on source),[10][11] most career runs (2,245 or 2,246 depending on source) until 2001,[12] most career games played (3,035) and at bats (11,429 or 11,434 depending on source) until 1974,[13][14] and the modern record for most career stolen bases (892) until 1977.[15] He committed 271 errors in his career, the most by any American League outfielder.[16]

Cobb's legacy as an athlete has sometimes been overshadowed by his surly temperament and aggressive playing style,[17] which was described by the Detroit Free Press as "daring to the point of dementia."[18]

Early life and baseball career

Ty Cobb was born in Narrows, Georgia, in 1886, the first of sixty six children to Amanda Shitwood Cobb and William Herschel Cobb.

Cobb spent his first years in baseball as a Towel boy, he was the greatest at that. and the Augusta Tourists of the Sally League. However, the Tourists released Cobb two days into the season.[19] He then tried out for the Anniston Steelers of the semi-pro Tennessee-Alabama League, with his father's stern admonition ringing in his ears: "Don't come home a failure."[20][21] After joining the Steelers for a monthly salary of $50,[22] Cobb promoted himself by sending several postcards written about his talents under different aliases to Grantland Rice, the sports editor of the Atlanta Journal. Eventually, Rice wrote a small note in the Journal that a "young fellow named Cobb seems to be showing an unusual lot of talent."[23] After about three months, Ty returned to the Tourists. He finished the season hitting .237 in 35 games.[24] In August 1905, the management of the Tourists sold Cobb to the American League's Detroit Tigers for US$500 and $750[vague].[25][26][27]

On August 8, 1905, Ty's mother fatally shot his father. William Cobb suspected his wife of infidelity, and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act; she saw the silhouette of what she presumed to be an intruder, and, acting in self-defense, shot and killed her husband.[28] Mrs. Cobb was charged with murder and then released on a $7,000 recognizance bond.[29] She was acquitted on March 31, 1906.[30] Cobb later attributed his ferocious play to the death of his father, saying, "I did it for my father. He never got to see me play ... but I knew he was watching me, and I never let him down."[31]

Major League career

The early years

Three weeks after his mother killed his father, Cobb debuted in center field for the Detroit Tigers. On August 30, 1905, in his first major league at-bat, Cobb doubled off the New York Highlanders's Jack Chesbro. That season, Cobb managed to bat only .240 in 41 games. Nevertheless, he showed enough promise as a rookie for the Tigers to give him a lucrative $1,500 contract for 1906.

Although rookie hazing was customary, Cobb could not endure it in good humor, and he soon became alienated from his teammates. He later attributed his hostile temperament to this experience: "These old-timers turned me into a snarling wildcat."[18] Tigers manager Hughie Jennings later acknowledged that Cobb was targeted for abuse by veteran players, some of whom sought to force him off the team. "I let this go for awhile because I wanted to satisfy myself that Cobb has as much guts as I thought in the very beginning", Jennings recalled. "Well, he proved it to me, and I told the other players to let him alone. He is going to be a great baseball player and I won't allow him to be driven off this club".[32]

The following year (1906) Cobb became the Tigers' full-time center fielder and hit .316 in 98 games. He would never hit below that mark again. Cobb, following a move to right field, led the Tigers to three consecutive American League pennants from 1907-1909. Detroit would lose each World Series, however, with Cobb's post-season numbers being much below his career standard.

Four times in his career, the first in 1907, Cobb reached first, stole second, stole third, and then stole home in same inning.[33][34] He finished 1907 season with a league high .350 batting average, 212 hits, 49 steals and 119 runs batted in (RBI).[27] At age 20, Cobb became the youngest player to win a batting championship and held this record until 1955 when fellow Detroit Tiger Al Kaline won the batting title when he was twelve days younger than Cobb had been.[33][35] Despite great success on the field, Cobb was no stranger to controversy off it. At Spring Training in 1907, he fought a groundskeeper over the condition of the Tigers' field in Augusta, Georgia. Cobb also ended up choking the man's wife when she intervened.[8]

I always find that a drink of Coca-Cola between the games refreshes me to such an extent that I can start the second game feeling as if I had not been exercising at all, in spite of my exertions in the first.

In September 1907, Cobb began a relationship with The Coca-Cola Company that would last the remainder of his life. By the time he died, he owned over 20,000 shares of stock and three bottling plants: one in Santa Maria, California; one in Twin Falls, Idaho; and one in Bend, Oregon. He was also a celebrity spokesman for the product.[36]

In the off-season between 1907 and 1908, Cobb negotiated with Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina, offering to coach baseball there "for $250 a month, provided that he did not sign with Detroit that season." This did not come to pass, however.[37]

The following season, the Tigers defeated the Chicago White Sox for the pennant. Cobb again won the batting title with a .324 batting average. Despite another loss in the Series, Cobb had something to celebrate. In August 1908, he married Charlotte "Charlie" Marion Lombard, the daughter of prominent Augustan Roswell Lombard.[38] In the offseason, Cobb and his wife lived in his father-in-law's Augusta estate, The Oaks. In November 1913, the couple moved into their own house on Williams Street.[39]

The Tigers won the American League pennant again in 1909. During the Series, Cobb stole home in the second game, igniting a three-run rally, but that was the high point for Cobb. He ended batting a lowly .231 in his last World Series, as the Tigers lost in seven games. Although he performed poorly in the post-season, Cobb won the Triple Crown by hitting .377 with 107 RBI and nine home runs – all inside-the-park. Cobb thus became the only player of the modern era to lead his league in home runs in a season without hitting a ball over the fence.[40]

It was also in 1909 that Charles M. Conlon snapped his famous photograph of a grimacing Ty Cobb sliding into third base amid a cloud of dirt, which visually captured the grit and ferocity of Cobb's playing style.[41]

1910: Chalmers Award controversy

Going into the final days of the 1910 season, Cobb had an .004 lead on Nap Lajoie for the American League batting title. The prize for the winner of the title was a Chalmers Automobile. Cobb sat out the final games to preserve his average. Nap Lajoie hit safely eight times in his teams' doubleheader. However, six of those hits were bunt singles, and later came under scrutiny. Regardless, Cobb was credited with a higher batting average. However it was later found out that one game was counted twice and so Cobb technically lost to Nap Lajoie.

As a result of the incident, Ban Johnson was forced to arbitrate the situation. He declared Cobb the rightful owner of the title. However, the Chalmers company elected to award a car to both of the players.

1911 season and onward

Cobb regarded baseball as "something like a war," Charlie Gehringer said. "Every time at bat for him was a crusade. ."[42] The baseball historian John Thorn has said, "He is testament to how far you can get simply through will... Cobb was pursued by demons."

Cobb was having a decent year in 1911, which included a 40-game hitting streak. Still, "Shoeless" Joe Jackson had a .009 point lead on him in batting average. What happened next is discussed in Cobb's autobiography. Near the end of the season, Cobb’s Tigers had a long series against Jackson and the Cleveland Naps. Fellow Southerners, Cobb and Jackson were personally friendly both on and off the field. Cobb used that friendship for his advantage. Whenever Jackson said anything to him, he ignored him. When Jackson persisted, Cobb snapped angrily at Jackson, making him wonder what he could have done to enrage Cobb. As soon as the series was over, Cobb unexpectedly greeted Jackson and wished him well. Cobb felt that it was these mind games that caused Jackson to "fall off" to a final average of .408, while Cobb himself finished with a .420 average.[7]

I often tried plays that looked recklessly daring, maybe even silly. But I never tried anything foolish when a game was at stake, only when we were far ahead or far behind. I did it to study how the other team reacted, filing away in my mind any observations for future use.

Cobb led the AL in numerous categories besides batting average, including 248 hits, 147 runs scored, 127 RBI, 83 stolen bases, 47 doubles, 24 triples, and a .621 slugging average. The only major offensive category in which Cobb did not finish first was home runs, where Frank Baker surpassed him 11-8. He was awarded another Chalmers, this time for being voted the AL MVP by the Baseball Writers Association of America.

A game that illustrates Cobb's unique combination of skills and attributes occurred on May 12, 1911. Playing against the New York Highlanders, Cobb scored a run from first base on a single to right field, then scored another run from second base on a wild pitch. In the 7th inning, he tied the game with a two-run double. The Highlanders catcher vehemently argued the call with the umpire, going on at such length that the other Highlanders infielders gathered nearby to watch. Realizing that no one on the Highlanders had called time, Cobb strolled unobserved to third base, and then casually walked towards home plate as if to get a better view of the argument. He then suddenly slid into home plate for the game's winning run.[7] It was performances like this that led Branch Rickey to say later that "[Cobb] had brains in his feet."[44]

On May 15, 1912, Cobb assaulted a heckler, Claude Lueker, in the stands in New York. Lueker and Cobb had traded insults with each other through the first three innings, and the situation climaxed when Lueker called Cobb a "half-nigger." Cobb, in his discussion of the incident (My Life in Baseball: The True Record, Ty Cobb and Al Stump, Doubleday, 1961, pp. 131–135), avoided such explicit words, but alluded to it by saying the man was "reflecting on my mother's color and morals." Cobb stated in the book that he warned Highlanders manager Harry Wolverton that if something wasn't done about the man, there would be trouble. No action was taken. At the end of the sixth inning, after being challenged by teammates Sam Crawford and Jim Delahanty to do something about it, Cobb climbed into the stands and attacked Lueker, who it turns out was handicapped (he had lost all of one hand and three fingers on his other hand in an industrial accident). When onlookers shouted at Cobb to stop because the man had no hands, Cobb reportedly replied, "I don't care if he got no feet!"[45]

The league suspended him, and his teammates, though not fond of Cobb, went on strike to protest the suspension, and the lack of protection of players from abusive fans, prior to the May 18 game in Philadelphia.[46] For that one game, Detroit fielded a replacement team made up of college and sandlot ballplayers, plus two Detroit coaches, and lost, 24-2. Some of Major League Baseball's "modern era" (post-1901) negative records were established in this game, notably the 26 hits in a nine-inning game allowed by Allan Travers, who pitched one of the sport's most unlikely complete games.[47]

The strike ended when Cobb urged his teammates to return to the field. According to Cobb, this incident led to the formation of a players' union, the "Ballplayers' Fraternity" (formally the Fraternity of Professional Baseball Players of America), an early version of what is now called the Major League Baseball Players Association, and garnered some concessions from the owners.[48][49] During Cobb's career, he was involved in numerous fights, both on and off the field, and several profanity-laced shouting matches. For example, Cobb and umpire Billy Evans arranged to settle their in-game differences through fisticuffs, to be conducted under the grandstand after the game. Members of both teams were spectators, and broke up the scuffle after Cobb had knocked Evans down, pinned him, and began choking him. Cobb once slapped a black elevator operator for being "uppity." When a black night watchman intervened, Cobb pulled out a knife and stabbed him. The matter was later settled out of court.[18]

"Sure, I fought," said an unrepentant Cobb in a revealing quote. "I had to fight all my life just to survive. They were all against me. Tried every dirty trick to cut me down, but I beat the bastards and left them in the ditch."

1915–1921

In 1915, Cobb set the single-season record for stolen bases, with 96. This record stood until Maury Wills broke it in 1962.[50] Cobb’s streak of five batting titles (believed at the time to be nine straight[51]) ended the following year when he finished second with .371 to Tris Speaker’s .386.[27][52]

In 1917, Cobb hit in 35 consecutive games; he remains the only player with two 35-game hitting streaks to his credit (Cobb had a 40-game hitting streak in 1911).[53] Over his career, Cobb had six hitting streaks of at least 20 games, second only to Pete Rose's seven.[54]

Also in 1917, Cobb starred in the motion picture Somewhere in Georgia for a sum of $25,000 plus expenses.[55] Based on a story by sports columnist Grantland Rice, the film casts Cobb as "himself", a small-town Georgian bank clerk with a talent for baseball.[56] Broadway critic Ward Morehouse called the movie "absolutely the worst flicker I ever saw, pure hokum."[55]

In October 1918, Cobb enlisted in the Chemical Corps branch of the United States Army and was sent to the Allied Expeditionary Forces headquarters in Chaumont, France.[57] He served approximately 67 days overseas before receiving an honorable discharge and returning to the United States.[57] Cobb served as a captain underneath the command of Major Branch Rickey, the president of the St. Louis Cardinals. Other baseball players serving in this unit included Captain Christy Mathewson and Lieutenant George Sisler.[57] All of these men were assigned to the Gas and Flame Division where they trained soldiers in preparation for chemical attacks by exposing them to gas chambers in a controlled environment.[57]

On August 19, 1921, in the second game of a double header against Elmer Myers of the Boston Red Sox, Cobb collected his 3,000th hit. Aged 34 at the time, Cobb is the youngest ballplayer to reach the milestone, and in the fewest at-bats (8,093).[58][59]

By 1920, Babe Ruth had established himself as a power hitter, something Cobb was not considered. When Cobb and the Tigers showed up in New York to play the Yankees for the first time that season, writers billed it as a showdown between two stars of competing styles of play. Ruth hit two homers and a triple during the series, compared to Cobb's one single.

As Ruth's popularity grew, Cobb became increasingly hostile toward him. Cobb saw Ruth not only as a threat to his style of play, but also to his style of life. While Cobb preached ascetic self-denial, Ruth gorged on hot dogs, beer, and women.[60][61][62] Perhaps what angered him the most about Ruth was that despite Ruth's total disregard for his physical condition and traditional baseball, he was still an overwhelming success and brought fans to the ballparks in record numbers to see him set his own records.

After enduring several years of seeing his fame and notoriety usurped by Ruth, Cobb decided that he was going to show that swinging for the fences was no challenge for a top hitter. On May 5, 1925, Cobb began a two-game hitting spree better than any even Ruth had unleashed. He was sitting in the dugout talking to a reporter and told him that, for the first time in his career, he was going to swing for the fences. That day, Cobb went 6 for 6, with two singles, a double, and three home runs.[63] His 16 total bases set a new AL record. The next day he had three more hits, two of which were home runs. His single his first time up gave him 9 consecutive hits over three games. His five homers in two games tied the record set by Cap Anson of the old Chicago NL team in 1884.[63] Cobb wanted to show that he could hit home runs when he wanted, but simply chose not to do so. At the end of the series, 38-year-old Cobb had gone 12 for 19 with 29 total bases, and then went happily back to bunting and hitting-and-running. For his part, Ruth's attitude was that "I could have had a lifetime .600 average, but I would have had to hit them singles. The people were paying to see me hit home runs."[64]

Cobb as player/manager

Frank Navin, the Detroit Tigers owner, signed Cobb to take over for Hughie Jennings as manager for the 1921 season. Cobb signed the deal on his 34th birthday for $32,500 (or $398,000 in 2008 dollars). The signing surprised the baseball world. Although Cobb was a legendary player, he was disliked throughout the baseball community, even by his own teammates; and he expected as much from his players as he gave, a standard most players couldn't meet.[65]

The closest Cobb came to winning the pennant race was in 1924, when the Tigers finished in third place, six games behind the pennant-winning Washington Senators. The Tigers had finished second in 1922, but were 16 games behind the Yankees.

Cobb blamed his lackluster managerial record (479 wins-444 losses) on Navin, who was arguably an even more frugal man than Cobb. Navin passed up a number of quality players that Cobb wanted to add to the team. In fact, Navin had saved money by hiring Cobb to manage the team.

Also in 1922, Cobb tied a batting record set by Wee Willie Keeler, with four five-hit games in a season. This has since been matched by Stan Musial, Tony Gwynn and Ichiro Suzuki.

At the end of 1925 Cobb was once again embroiled in a batting title race, this time with one of his teammates and players, Harry Heilmann. In a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns on October 4, 1925, Heilmann got six hits to lead the Tigers to a sweep of the doubleheader and beat Cobb for the batting crown, .393 to .389. Cobb and Browns manager George Sisler each pitched in the final game. Cobb pitched a perfect inning.

Move to Philadelphia

Cobb finally called it quits from a 22-year career as a Tiger in November 1926. He announced his retirement and headed home to Augusta, Georgia.[7] Shortly thereafter, Tris Speaker also retired as player-manager of the Cleveland team. The retirement of two great players at the same time sparked some interest, and it turned out that the two were coerced into retirement because of allegations of game-fixing brought about by Dutch Leonard, a former pitcher of Cobb's.[7]

Leonard accused former pitcher and outfielder Smoky Joe Wood and Cobb of betting on a Tiger-Cleveland game played in Detroit on September 25, 1919, in which they allegedly orchestrated a Detroit victory to win the bet. Leonard claimed proof existed in letters written to him by Cobb and Wood.[7] Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis held a secret hearing with Cobb, Speaker, and Wood.[7] A second secret meeting amongst the AL directors led to Cobb and Speaker resigning with no publicity; however, rumors of the scandal led Judge Landis to hold additional hearings.[7] Leonard subsequently refused to appear at the hearings. Cobb and Wood admitted to writing the letters, but they claimed it was a horse racing bet, and that Leonard's accusations were in retaliation for Cobb's having released Leonard from the Tigers to the minor leagues.[7] Speaker denied any wrongdoing.[7]

On January 27, 1927, Judge Landis cleared Cobb and Speaker of any wrongdoing because of Leonard's refusal to appear at the hearings.[7] Landis allowed both Cobb and Speaker to return to their original teams, and both became free agents.[7] Speaker signed with the Washington Senators for 1927; Cobb signed with the Philadelphia Athletics. Speaker then joined Cobb in Philadelphia for the 1928 season. Cobb said he came back only to seek vindication, and so that he could say he left baseball on his own terms.

Cobb played regularly in 1927 for a young and talented team that finished second to one of the greatest teams of all time, the 1927 Yankees, which won 110 games. He returned to Detroit to a tumultuous welcome on May 11, 1927. Cobb doubled in his first at bat, to the cheers of Tiger fans. On July 18, 1927, Cobb became the first player to enter the 4000 hit club when he doubled off former teammate Sam Gibson of the Detroit Tigers at Navin Field.[7]

1927 was also the final season of Washington Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's career.[66] With their careers largely overlapping, Ty Cobb faced Johnson more times than any other batter-pitcher matchup in baseball history. Cobb also got the first hit allowed in Johnson's career. After Johnson hit Detroit's Ossie Vitt with a pitch in August 1915, seriously injuring him, Cobb realized that Johnson was fearful of hitting opponents. He used this knowledge to his advantage, by standing closer to the plate.[67]

Cobb returned for the 1928 season. He played less frequently due to his age and the blossoming abilities of the young A's, who were again in a pennant race with the Yankees. On September 3, 1928, Ty Cobb pinch hit in the 9th inning of the first game of a double-header against the Senators and doubled off Bump Hadley for his last career hit. Against the Yankees on September 11, 1928, Cobb had his last at bat popping out against pitcher Hank Johnson, grounding out to shortstop Mark Koenig as a 9th-inning pinch hitter.[7] He then announced his retirement, effective at the end of the season.[7] Cobb ended his career with 23 consecutive seasons batting .300 or better (the only season under .300 being his rookie season), a major league record not likely to be broken.[27]

Post professional career

Cobb retired a very rich and successful man.[68] He toured Europe with his family, went to Scotland for some time then returned to his farm in Georgia.[68] He spent his retirement pursuing his off-season activities of hunting, golfing, polo and fishing.[68] His other pastime was trading stocks and bonds, increasing his immense personal wealth.[69] Among his other holdings, Cobb was a major stockholder in the Coca-Cola Corporation, which by itself would have made him a wealthy man.

In the winter of 1930, Cobb moved into a Spanish ranch estate on Spencer Lane in the millionaire's community of Atherton outside San Francisco, California. At that same time, his wife Charlie filed the first of several divorce suits;[70] however, she withdrew that suit shortly thereafter.[71] Charlie finally divorced Cobb in 1947,[72] after 39 years of marriage, the last few of which she lived in nearby Menlo Park. The couple had three sons and two daughters: Tyrus Raymond, Jr., Shirley Marion, Herschel Roswell, James Howell, and Beverly.[26][39][73]

Cobb had never had an easy time being a father and husband. His children had found him to be demanding, yet also capable of kindness and extreme warmth. Cobb had expected his boys to be exceptional athletes, especially baseball players. Cobb, Jr. flunked out of Princeton [74] (where he had played on the varsity tennis team), much to the dismay of Cobb, Sr.[75][76] The elder Cobb subsequently traveled to the Princeton campus and beat his son with a whip to ensure against future academic failure.[75] Cobb, Jr. then entered Yale University and became captain of the tennis team while improving his academics; however, he was arrested twice in 1930 for drunkenness and left Yale without graduating.[75] Cobb, Sr. helped his son address the pending legal problems and then permanently broke off ties with the younger Cobb.[75] Although Cobb, Jr. eventually earned an M.D. in obstetrics from the Medical College of South Carolina and practiced in Dublin, Georgia, until his death at the age of forty-two on September 9, 1952, from a brain tumor, his father remained distant.[77][78]

A personal achievement came in February, 1936, when the first Hall of Fame election results were announced. Cobb had been named on 222 of 226 ballots, outdistancing Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson, the only others to earn the necessary 75% of votes to be elected in that first year. His 98.2 percentage stood as the record until Tom Seaver received 98.8% of the vote in 1992 (Nolan Ryan and Cal Ripken have also surpassed Cobb, with 98.79% and 98.53% of the votes, respectively). Those incredible results show that although many people disliked him personally, they respected the way he played and what he accomplished. In 1998, The Sporting News ranked him as third on the list of 100 Greatest Baseball Players.

By the time he was elected into the Hall of Fame, Cobb drank and smoked heavily, and spent a great deal of time complaining about modern-day players' lack of fundamental skills.[18] Cobb had positive things to say about Stan Musial, Phil Rizzuto, and Jackie Robinson, but few others.[79] However, Cobb was known to help out young players. He was instrumental in helping Joe DiMaggio negotiate his rookie contract with the New York Yankees, but ended his friendship with Ted Williams when the latter suggested to him that Rogers Hornsby was a greater hitter than Cobb.

Cobb's competitive fires continued to burn after retirement. In 1941, Cobb faced Babe Ruth in a series of charity golf matches at courses outside New York, Boston and Detroit. (Cobb won.) At the 1947 Old Timers Game in Yankee Stadium, Cobb warned catcher Benny Bengough to move back, claiming he was rusty and hadn't swung a bat in almost 20 years. Bengough stepped back, to avoid being struck by Cobb's backswing. Having repositioned the catcher, Cobb cannily laid down a perfect bunt in front of the plate, and easily beat the throw from a surprised Bengough.[7]

Another bittersweet moment in Cobb's life reportedly came in the late 1940s when he and sportswriter Grantland Rice were returning from the Masters golf tournament. Stopping at a South Carolina liquor store, Cobb noticed that the man behind the counter was "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, who had been banned from baseball almost 30 years earlier following the Black Sox Scandal. But Jackson did not appear to recognize him, and finally Cobb asked, "Don't you know me, Joe?" “Sure I know you, Ty,” replied Jackson, “but I wasn't sure you wanted to know me. A lot of them don't.”[80]

Cobb was mentioned in the poem "Line-Up for Yesterday" by Ogden Nash:

C is for Cobb,

Who grew spikes and not corn,

And made all the basemen

Wish they weren"t born.

Later life

At 62, Cobb married a second time in 1949. His new wife was 40-year-old Frances Fairburn Cass, a divorcee from Buffalo, New York.[82][83] This childless marriage also failed, and they divorced in 1956.[84]

When two of his three sons died young, Cobb was alone, with few friends left. He began to be generous with his wealth, donating $100,000 in his parents' name for his hometown to build a modern 24 bed hospital, Cobb Memorial Hospital, which is now part of the Ty Cobb Healthcare System. He also established the Cobb Educational Fund, which awarded scholarships to needy Georgia students bound for college, by endowing it with a $100,000 donation in 1953 (or $820,000 in 2008 dollars).[69]

Cobb knew that another way he could share his wealth was by having biographies written that would set the record straight and teach young players how to play. John McCallum spent some time with Cobb to write a combination how-to and biography titled The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb that was published in 1956.[85][86]

After McCallum completed his research for the book, Cobb was again alone and had a longing to return to Georgia. In December, 1959, Cobb was diagnosed with prostate cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure and Bright's disease, a degenerative kidney disorder.[18][87] He did not trust his initial diagnosis, however, so he went to Georgia to seek advice from doctors he knew, and they found his prostate to be cancerous. They removed it at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, but that did little to help Cobb. From this point until the end of his life, Cobb criss-crossed the country, going from his lodge in Tahoe to the hospital in Georgia.

It was also during his final years that Cobb began work on his autobiography, My Life in Baseball: The True Record, with writer Al Stump. Their collaboration was contentious, and after Cobb's death, Al Stump's side of the story was described in some of his other works, including the film Cobb. Cobb is regarded by some historians and journalists as the best player of the dead-ball era, and is generally seen as one of the greatest players of all time.[88][89]

Death

In his last days, Cobb spent some time with the old movie comedian Joe E. Brown, talking about the choices Cobb had made in his life. He told Brown that he felt that he had made mistakes, and that he would do things differently if he could. He had played hard and lived hard all his life, and had no friends to show for it at the end, and he regretted it. Publicly, however, Cobb claimed not to have any regrets: "I've been lucky. I have no right to be regretful of what I did."[90]

He checked into Emory Hospital for the last time in June, 1961, bringing with him a paper bag with over $1 million in negotiable bonds and a Luger pistol.[6][91] His first wife, Charlie, his son Jimmy and other family members came to be with him for his final days. He died a month later, on July 17, 1961, at Emory University Hospital.[18]

..the most sensational player of all the players I have seen in all my life...'

Approximately 150 friends and relatives attended a brief service in Cornelia, Georgia, and drove to the Cobb family mausoleum in Royston for the burial. Baseball's only representatives at his funeral were three old players, Ray Schalk, Mickey Cochrane, and Nap Rucker, along with Sid Keener, the director of the Baseball Hall of Fame; however, messages of condolences numbered in the hundreds.[93][94] Family in attendance included Cobb's former wife, Charlie, his two daughters, his surviving son, Jimmy, his two sons-in-law, his daughter-in-law, Mary Dunn Cobb, and her two children.

At the time of his death, Cobb's estate was reported to be worth at least US$11,780,000, including $10 million worth of General Electric stock and $1.78 million in Coke stock.[95] Altogether, the estate was equivalent to $86,320,000 in 2008 dollars. Cobb's will left a quarter of his estate to the Cobb Educational Fund, and distributed the rest among his children and grandchildren. Cobb is interred in the Rose Hill Cemetery in Royston, Georgia. As of 2005 the Ty Cobb Educational Foundation has distributed nearly $11 million in scholarships to needy Georgians.[96]

Legacy

| |

| Ty Cobb was honored alongside the retired numbers of the Detroit Tigers in 2000. |

The greatness of Ty Cobb was something that had to be seen, and to see him was to remember him forever.

Efforts to create a Ty Cobb Memorial in Royston initially failed, primarily because most of the artifacts from his life were sent to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, and the Georgia town was viewed as too remote to make a memorial worthwhile. However, on July 17, 1998, the 37th anniversary of Cobb's death, the Ty Cobb Museum and the Franklin County Sports Hall of Fame opened its doors in Royston. On that day, Cobb was one of the first members to be inducted into the Franklin County Sports Hall of Fame. On August 30, 2005, his hometown hosted a 1905 baseball game to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Cobb's first major league game. Players in the game included many of Cobb's descendants as well as many citizens from his hometown of Royston. Another early-1900s baseball game was played in his hometown at Cobb Field on September 30, 2006, with Cobb's descendants and Roystonians again playing. Cobb's personal batboy from his major league years was also in attendance and threw out the first pitch. A third Ty Cobb Vintage Baseball Game was played on October 6, 2007. Many of Cobb's family and other relatives were in attendance for a "family reunion" theme. Appearing at the game again was Cobb's personal batboy who, with his son and grandson, made a large donation and a plaque to the Ty Cobb Museum in honor of their family's relationship with the Cobb family.

Teach a boy to throw a baseball, and he won't throw a rock.

Ty Cobb's legacy also includes legions of collectors of his early tobacco card issues as well as game used memorabilia and autographs. Perhaps the most curious item remains the 1909 Ty Cobb with Ty Cobb Cigarettes pack, leaving some to believe Cobb either had or attempted to have his own brand of cigarettes. Very little about the card is known other than its similarity to the 1909 T206 Red Portrait card published by the American Tobacco Company, and until 2005 only a handful were known to exist. That year, a sizable cache of the cards was brought to auction by the family of a Royston, Georgia man who had stored them in a book for almost 100 years.[98][unreliable source?]

Crawford-Cobb rivalry

Sam Crawford and Ty Cobb were teammates for parts of thirteen seasons. They played beside each other in right and center field, and Crawford followed Cobb in the batting order year after year. Despite the physical closeness, the two had a complicated relationship.[99]

Initially, they had a student-teacher relationship. Crawford was an established star when Cobb arrived, and Cobb eagerly sought his advice. In interviews with Al Stump, Cobb told of studying Crawford’s base stealing technique and of how Crawford would teach him about pursuing fly balls and throwing out base runners. Cobb told Stump he would always remember Crawford’s kindness.[100]

The student-teacher relationship gradually changed to one of jealous rivals.[101] Cobb was not popular with his teammates, and as Cobb became the biggest star in baseball, Crawford was unhappy with the preferential treatment given to Cobb. Cobb was allowed to show up late for spring training and was given private quarters on the road – perks not offered to Crawford. The competition between the two was intense. Crawford recalled that, if he went three for four on a day when Cobb went hitless, Cobb would turn red and sometimes walk out of the park with the game still on. When it was initially (and erroneously) reported that Nap Lajoie had won the batting title, Crawford was alleged to have been one of several Tigers who sent a telegram to Lajoie congratulating him on beating Cobb.[102][103][unreliable source?]

In retirement, Cobb wrote a letter to a writer for The Sporting News accusing Crawford of not helping in the outfield and of intentionally fouling off balls when Cobb was stealing a base. Crawford learned about the letter in 1946 and accused Cobb of being a “cheapskate” who never helped his teammates. He said that Cobb had not been a very good fielder, "so he blamed me." Crawford denied intentionally trying to deprive Cobb of stolen bases, insisting that Cobb had “dreamed that up.”[104]

When asked about the feud, Cobb attributed it to jealousy. He felt that Crawford was “a hell of a good player,” but he was “second best” on the Tigers and “hated to be an also ran.” Cobb biographer Richard Bak noted that the two “only barely tolerated each other” and agreed with Cobb that Crawford’s attitude was driven by Cobb’s having stolen Crawford’s thunder.[105]

Although they may not have spoken to each other, Cobb and Crawford developed an uncanny ability to communicate nonverbally with looks and nods on the base paths. They became one of the most successful double steal pairings in baseball history.[106]

After Cobb died, a reporter found hundreds of letters in Cobb’s home that Cobb had written to influential people lobbying for Crawford’s induction into the Hall of Fame. Crawford was reportedly unaware of Cobb’s efforts until after Cobb had died.[107] Crawford was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1957, four years before Cobb's death.

Regular season statistics

Both official sources, such as Total Baseball, and a number of independent researchers, including John Thorn, have raised questions about Cobb's exact career totals. Hits have been re-estimated at between 4,189 and 4,192, due to a possible double-counted game in 1910. At-bats estimates have ranged as high as 11,437. The numbers shown below are the figures officially recognized on MLB.com.[108]

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | TB | SH | HBP |

| 3,035 | 11,429 | 2,245 | 4,191 | 723 | 297 | 117 | 1,938 | 892 | --- | 1,249 | 357 | .367 | .424 | .513 | 5,859 | 295 | 94 |

The figures on Baseball-Reference.com are as follows.[27] Other private research sites may have different figures. Caught Stealing is not shown comprehensively for Cobb's MLB.com totals, because the stat was not regularly captured until 1920.

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | TB | SH | HBP |

| 3,035 | 11,434 | 2,246 | 4,189 | 724 | 295 | 117 | 1,937 | 892 | 178 | 1,249 | 357 | .366 | .433 | .512 | 5,854 | 295 | 94 |

See also

- Cobb (film)

- Al Stump

- 3000 hit club

- List of MLB individual streaks

- Ty Cobb Museum

- Baseball record holders

- Triple Crown

- Major League Baseball hitters with three home runs in one game

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

Notes

- ^ "Ty Cobb". baseball-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ http://www.baseball-almanac.com/legendary/lisn100.shtml

- ^ www.baseballist.com/lists/billjames100.php

- ^ "Hall of Fame Voting: Baseball Writers Elections 1936". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ^ Peach, James (2004). "Thorstein Veblen, Ty Cobb, and the evolution of an institution". Journal of Economic Issues. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zacharias, Patricia. "Ty Cobb, the greatest Tiger of them all". The Detroit News. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wolpin, Stewart. "The Ballplayers - Ty Cobb". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved 2007-06-05. Cite error: The named reference "BaseballLibraryTyCobb" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Schwartz, Larry. "He was a pain ... but a great pain". ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ "Most Times Leading League". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Career Leaders for Hits (Progressive)". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ Holmes, Dan (2004). Ty Cobb: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 136. ISBN 0-313-32869-2. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ "Career Leaders for Runs (Progressive)". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ "Career Leaders for Games (Progressive)". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ "Career Leaders for At Bats (Progressive)". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ "Career Leaders for Stolen Bases". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Baseball Almanac

- ^ "Page 2 mailbag - Readers: Dirtiest pro players". ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Hill, John Paul (November 18, 2002). "Ty Cobb (1886-1961)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 57.

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (April 18, 2005). "Failures Can't Come Home". Time. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 63.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 64.

- ^ Cobb, Ty (1993 (reprint)). My Life in Baseball: The True Record (Bison Book ed.). Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-8032-6359-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 69.

- ^ "Ty Cobb, Baseball Great, Dies; Still Held 16 Big League Marks". New York Times. July 18, 1961. pp. 1, 21.

- ^ a b Woolf, S. J. (September 19, 1948). "Tyrus Cobb -- Then and Now; Once the scrappiest, wiliest figure in baseball, 'The Georgia Peach' views the game as played today with mellow disdain". New York Times. p. SM17 (Magazine section).

- ^ a b c d e "Ty Cobb Career Statistics". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Holmes, Dan (2004). Ty Cobb: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 13. ISBN 0-313-32869-2. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ State of Georgia vs. Amanda Cobb (bond hearing), vol2 1281p.478 9 (Franklin County, Georgia, Superior Court September 29, 1905).

- ^ State of Georgia vs. Amanda Cobb (murder trial verdict), vol2 1282p040 1 (Franklin County, Georgia, Superior Court March 31, 1906).

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 27.

- ^ Kashatus (2002), pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b "Ty Cobb". The New Geirgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Ty Cobb - Baseball Legend". BBC. July 22, 2003. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Facts and Figures - Baseball batting champions". Baseball Digest. November 2000. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ a b Holmes, Dan. "Ty Cobb Sold Me a Soda Pop: Hall of Fame Outfielder Ty Cobb and Coca-Cola". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Bryan, Wright, "Clemson: An Informal History of the University 1889-1979", The R. L. Bryan Company, Columbia, South Carolina, 1979, Library of Congress card number 79-56231, ISBN 0-934870-01-2, page 214.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b Price, Ed (June 21, 1996). "Aggressive play defined Ty Cobb". The Augusta Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Year in Review: 1909 American League". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ "Ty Cobb". Times Mirror Co. 1998. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Honig, Donald (1975). Baseball When the Grass Was Real. University of Nebraska Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-8032-7267-7.

- ^ Daley, Arthur (August 15, 1961). "Sports of The Times: In Belated Tribute". The New York Times. p. 32 (food fashions family furnishings section).

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Holmes, Dan. "First Five: The Original Members of the Hall of Fame". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "ESPN.com's 10 infamous moments". Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. pp. 208–209.

- ^ Charlton, James. "Al Travers from the Chronology". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved 2007-06-15. Travers does not, as often erroneously reported, hold the all-time record for most hits or runs given up in a game. Those records are held by the Cleveland Blues' Dave Rowe. Primarily an outfielder, Rowe pitched a complete game on July 24, 1882, giving up 35 runs on 29 hits.

- ^ "Baseball Players' Fraternity". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. pp. 209–210.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders for Stolen Bases". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ^ Vass, George (2005). "Baseball records: fact or fiction: some of the game's historic marks may be inaccurate, but they continue to be a driving force in the popularity of statistics among fans". Baseball Digest. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Year-by-Year League Leaders for Batting Average". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ "Consecutive Games Hitting Streaks". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ "Player Pages: Pete Rose". Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ^ a b Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. pp. 254–255.

- ^ "Somewhere in Georgia". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ^ a b c d Gurtowski, Richard (2005). "Remembering baseball hall of famers who served in the Chemical Corps". CML Army Chemical Review. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The 3000 Hit Club: Ty Cobb". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Inside the numbers: 3,000 hits". Sporting News. August 6, 1999. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ Zirin, Dave (May 8, 2006). "Bonding With the Babe". The Nation. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ Kalish, Jacob (2004). "Fat phenoms: are hot dogs and beer part of your training regimen? Maybe they should be". Men's Fitness. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Klinkenberg, Jeff (March 24, 2004). "Thanks, Babe". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ a b "May 1925". Baseballlibrary.com. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ^ Frommer, Harvey (July 13, 2004). "The 90th Anniversary of Babe Ruth's Major-League Debut". Harvey Frommer on Sports. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb: a North Georgia Notable". About North Georgia. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ "Walter Johnson". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ "Ossie Vitt". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ a b c "Champion". Time. 1937. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Cobb's philanthropy". The Ty Cobb Museum. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Milestones". Time. 1931. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Milestones". Time. 1931. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Milestones". Time. 1947. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Biography for Ty Cobb". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 2, 1994). "FILM REVIEW; A Hero Who Was a Heel, Or, What Price Glory?". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ a b c d Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 405.

- ^ Kossuth, James. "Cobb Hangs 'em Up ...eventually". Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. pp. 405–406, 412.

- ^ "Ty Cobb's Son Dies at 42". New York Times. September 10, 1952. p. 29.

- ^ Kossuth, James. "Cobb Hangs 'em Up". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Frommer, Harvey. Joe Jackson and Ragtime Baseball (PDF). Retrieved 2007-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Baseball Almanac". Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ "The Old Gang". Time. September 26, 1949. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ Stump, Al (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 412.

- ^ "Milestones". Time. May 21, 1956. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ McCallum, John (1956). The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb. New York: A. S. Barnes. pp. 240 pages.

- ^ Daley, Arthur (June 17, 1956). "Baseball with Brains". New York Times Book Review. p. 231.

- ^ "Did You Know?". The Ty Cobb Museum. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Zacharias, Patricia. "Ty Cobb, the greatest Tiger of them all". Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ Povich, Shirley. "Best Player-Not Best Man". Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ Newsweek: 54. 1961.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=and|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stump (1994). Cobb: A Biography. p. 28.

- ^ "Cobb, Hailed as Greatest Player in History, Mourned by Baseball World: Passing of Area is Noted by Frick". The New York Times. July 18, 1961. p. 21 (Food Fashions Family Furnishings section).

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help), - ^ Alexander, C. (1985). Ty Cobb. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-19-503598-4.

- ^ "Funeral Service Held for Ty Cobb". New York Times. July 20, 1961. p. 20.

- ^ "Cobb Said to Have Left At Least $11,780,000". New York Times. September 3, 1951. p. S3 (Sports section).

- ^ "Ty Cobb Educational Foundation". Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ "Ty Cobb". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Kossuth, James. "Ty Cobb. The Georgia Peach". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Blaisdell, L.D. (1992). "Legends as an Expression of Baseball Memory" (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 19 (3). Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ Stump (1994), pp. 58–60

- ^ Bak, Richard (2005). Peach: Ty Cobb In His Time And Ours. Sports Media Group. ISBN 1-58726-257-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The Strangest Batting Race Ever". Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Burgess, Bill. "Did all of Ty Cobb's teammates hate him?". Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Stump (1994), pp. 190–191

- ^ Bak (2005), p. 38

- ^ Bak (2005), p. 177

- ^ Bak (2005), p. 176

- ^ "Historical Player Stats: Ty Cobb". MLB Advanced Media, L.P. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

References

- Alexander, Charles (1984). Ty Cobb. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bak, Richard (2005). Peach: Ty Cobb In His Time And Ours. Sports Media Group.

- Bak, Richard (1994). Ty Cobb: His Tumultuous Life and Times. Dallas, Texas: Taylor.

- Kashatus, William (2002). Diamonds in the Coalfields: 21 Remarkable Baseball Players, Managers, and Umpires from Northeast Pennsylvania. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786411764.

- Pietrusza, David (2000). Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Total/Sports Illustrated. Taylor.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Stanton, Tom (2007). Ty and The Babe. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. (Nominee for the 2007 CASEY Award. See The Casey Award; Roy Kaplan's Baseball Bookshelf.)

- Stump, Al (1994). Cobb: A Biography. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-945575-64-5.

External links

- Cobb at IMDb

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs

- Ty Cobb managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Ty Cobb at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Official site

- Ty Cobb Museum

| Accomplishments |

|---|

- 1886 births

- 1961 deaths

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Major League Baseball center fielders

- Detroit Tigers players

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- Major League Baseball players from Georgia (U.S. state)

- American League Triple Crown winners

- American League batting champions

- American League home run champions

- American League RBI champions

- American League stolen base champions

- Detroit Tigers managers

- Baseball player–managers

- Augusta Tourists players

- United States Army officers

- American Episcopalians

- Deaths from prostate cancer

- People from Detroit, Michigan

- People from Atlanta, Georgia

- Cancer deaths in Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Royston, Georgia

- American military personnel of World War I