Sindh

Template:Pakistan infobox Sindh (pronounced [sin̪d̪ʱ]: Template:Lang-sd, Template:Lang-ur is one of the four provinces of Pakistan and historically is home to the Sindhi people.It is also locally known as the "Mehran" (مهران) and "Bab-ul-Islam" (باب الاسلام) The Door to Islam, because Islam in the Indian subcontinent was first introduced from Sindh. Different cultural and ethnic groups also reside in Sindh including Urdu-speaking Muslim refugees who migrated to Pakistan from India upon independence as well as the people migrated from other provinces after independence. The neighbouring regions of Sindh are Balochistan to the west and north, Punjab to the north, Gujarat and Rajasthan to the southeast and east, and the Arabian Sea to the south. The main language is Sindhi. The name is derived from Sanskrit, and was known to the Assyrians (as early as the seventh century BCE) as Sinda, to the Greeks as Sinthus, to the Romans as Sindus, to the Persians as Abisind, to the Arabs as Al-Sind, and to the Chinese as Sintow. To the Javanese the Sindhis have long been known as the Santri.

Origin of the name

The province of Sindh and the people inhabiting the region had been designated after the river known in Ancient times as the Sindhus River, now also known by Indus River. In Sanskrit, síndhu means "river, stream". However, the importance of the river and close phonetical resemblance in nomenclature would make one consider síndhu as the probable origin of the name of Sindh. The Greeks who conquered Sindh in 325 BC under the command of Alexander the Great rendered it as Indós, hence the modern Indus, when the British conquered South Asia, they expanded the term and applied the name to the entire region of South Asia and called it India.

Prehistoric period

The Indus Valley civilization is the farthest visible outpost of archaeology in the abyss of prehistoric times. The prehistoric site of Kot Diji in Sindh has furnished information of high significance for the reconstruction of a connected story which pushes back the history of South Asia by at least another 300 years, from about 2500 BC. Evidence of a new element of pre-Harappan culture has been traced here. When the primitive village communities in Balochistan were still struggling against a difficult highland environment, a highly cultured people were trying to assert themselves at Kot Diji one of the most developed urban civilization of the ancient world that flourished between the year 25th century BC and 1500 BC in the Indus valley sites of Moenjodaro and Harappa. The people were endowed with a high standard of art and craftsmanship and well-developed system of quasi-pictographic writing which despite ceaseless efforts still remains un-deciphered. The remarkable ruins of the beautifully planned Moenjodaro and Harappa towns, the brick buildings of the common people, roads, public-baths and the covered drainage system envisage the life of a community living happily in an organized manner.

This civilisation is now identified as a possible pre-Aryan civilisation and most probably an indigenous civilization which was met its downfall around the year 1700BC. The downfall of the Indus Valley Civilization is still a hotly debated topic, and was probably caused by a massive earthquake, which dried up the Ghaggar River.

Geography and climate

Sindh is located on the western corner of South Asia, bordering the Iranian plateau in the west. Geographically it is the third largest province of Pakistan, stretching about 579 km from north to south and 442 km (extreme) or 281 km (average) from east to west, with an area of 140,915 square kilometres (54,408 square miles) of Pakistani territory. Sindh is bounded by the Thar Desert to the east, the Kirthar Mountains to the west, and the Arabian Sea in the south. In the centre is a fertile plain around the Indus river.

Sindh is situated in a subtropical region; it is hot in the summer and cold in winter. Temperatures frequently rise above 46 °C (115 °F) between May and August, and the minimum average temperature of 2 °C (36 °F) occurs during December and January. The annual rainfall averages about seven inches, falling mainly during July and August. The southwest monsoon wind begins to blow in mid-February and continues until the end of September, whereas the cool northerly wind blows during the winter months from October to January.

Sindh lies between the two monsoons — the southwest monsoon from the Indian Ocean and the northeast or retreating monsoon, deflected towards it by the Himalayan mountains — and escapes the influence of both. The average rainfall in Sindh is only 6–7 in (15–18 cm) per year. The region's scarcity of rainfall is compensated by the inundation of the Indus twice a year, caused by the spring and summer melting of Himalayan snow and by rainfall in the monsoon season. These natural patterns have recently changed somewhat with the construction of dams and barrages on the Indus River.

Sindh is divided into three climatic regions: Siro (the upper region, centred on Jacobabad), Wicholo (the middle region, centred on Hyderabad), and Lar (the lower region, centred on Karachi). The thermal equator passes through upper Sindh, where the air is generally very dry. Central Sindh's temperatures are generally lower than those of upper Sindh but higher than those of lower Sindh. Dry hot days and cool nights are typical during the summer. Central Sindh's maximum temperature typically reaches 43–44 °C (109–111 °F). Lower Sindh has a damper and humid maritime climate affected by the southwestern winds in summer and northeastern winds in winter, with lower rainfall than Central Sindh. Lower Sindh's maximum temperature reaches about 35–38 °C (95–100 °F). In the Kirthar range at 1,800 m (5,900 ft) and higher at Gorakh Hill and other peaks in Dadu District, temperatures near freezing have been recorded and brief snowfall is received in the winters.

Flora and fauna

The province is mostly arid with scant vegetation except for the irrigated Indus Valley. The dwarf palm, Acacia Rupestris (kher), and Tecomella undulata (lohirro) trees are typical of the western hill region. In the Indus valley, the Acacia nilotica (babul) (babbur) is the most dominant and occurs in thick forests along the Indus banks. The Azadirachta indica (neem) (nim), Zizyphys vulgaris (bir) (ber), Tamarix orientalis (jujuba lai) and Capparis aphylla (kirir) are among the more common trees.

Mango, date palms, and the more recently introduced banana, guava, orange, and chiku are the typical fruit-bearing trees. The coastal strip and the creeks abound in semi-aquatic and aquatic plants, and the inshore Indus delta islands have forests of Avicennia tomentosa (timmer) and Ceriops candolleana (chaunir) trees. Water lilies grow in abundance in the numerous lake and ponds, particularly in the lower Sindh region.

Among the wild animals, the Sindh ibex (sareh), wild sheep (urial or gadh) and black bear are found in the western rocky range, where the leopard is now rare. The pirrang (large tiger cat or fishing cat) of the eastern desert region is also disappearing. Deer occur in the lower rocky plains and in the eastern region, as do the striped hyena (charakh), jackal, fox, porcupine, common gray mongoose, and hedgehog. The Sindhi phekari, ped lynx or Caracal cat, is found in some areas. In the Kirthar national park of sind, there is a project to introduce tigers and Asian elephants.

Phartho (hog deer) and wild bear occur particularly in the central inundation belt. There are a variety of bats, lizards, and reptiles, including the cobra, lundi (viper), and the mysterious Sindh krait of the Thar region, which is supposed to suck the victim's breath in his sleep. Crocodiles are rare and inhabit only the backwaters of the Indus, eastern Nara channel and karachi backwater Besides a large variety of marine fish, the plumbeous dolphin, the beaked dolphin, rorqual or blue whale, and a variety of skates frequent the seas along the Sind coast. The pallo (sable fish), a marine fish, ascends the Indus annually from February to April to spawn.

Although Sindh has a semi arid climate, through its coastal and riverine forests, its huge fresh water lakes and mountains and deserts, Sindh supports a large amount of varied wildlife.

Due to the semi arid climate of Sindh The left out forests support average population of jackals and snakes. The national parks established by the Government of Pakistan in collaboration with many organizations such as World Wide Fund for Nature and Sindh Wildlife Department support a huge variety of animals and birds. The Kirthar National Park in the Kirthar range spreads over more than 3000 km² of desert, stunted tree forests and a lake. The KNP supports Sindh Ibex , wild sheep (urial) and black bear along with the rare leopard. There are also occasional sightings of The Sindhi phekari, ped lynx or Caracal cat. There is a project to introduce tigers and Asian elephants too in KNP near the huge Hub dam lake.

The Indus river dolphin is among the most endangered species in Pakistan and is found in the part of the Indus river in northern Sindh. Hog deer and wild bear occur particularly in the central inundation belt. There are also varieties of bats, lizards, and reptiles, including the cobra, lundi (viper).

Some unusual sightings of Asian Cheetah occurred in 2003 near the Balochistan Border in Kirthar mountains. The pirrang (large tiger cat or fishing cat) of the eastern desert region is also disappearing. Deer occur in the lower rocky plains and in the eastern region, as do the striped hyena (charakh), jackal, fox, porcupine, common gray mongoose, and hedgehog.

Between July and November when the monsoon winds blow onshore from the ocean, giant Olive Ridley turtles lay their eggs along the seaward side. The turtles are protected species. After the mothers lay and leave them buried under the sands the SWD and WWF officials take the eggs and protect them until they are hatched to protect them from predators.

Crocodiles are rare and inhabit only the backwaters of the Indus, the eastern Nara channel and some population of Marsh crocodiles can be very easily seen in the waters of Haleji Lake near Karachi. Besides a large variety of marine fish, the plumbeous dolphin, the beaked dolphin, rorqual or blue whale, and a variety of skates frequent the seas along the Sind coast. The pallo (sable fish), though a marine fish, ascends the Indus annually from February to April to spawn. The rare Houbara Bustard also find Sindh's warm climate suitable to rest and mate.

Demographics and society

| Sindh Demographic Indicators | |

|---|---|

| Indicator | Statistic |

| Urban population | 55.00% |

| Rural population | 45.00% |

| Population growth rate | 2.80% |

| Gender ratio (male per 100 female) | 112.24 |

| Economically active population | 22.75% |

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban |

|

| ||

| 1951 | 6,047,748 | 29.23% |

| 1961 | 8,367,065 | 37.85% |

| 1972 | 14,155,909 | 40.44% |

| 1981 | 19,028,666 | 43.31% |

| 1998 | 30,439,893 | 48.75% |

| 2009 | 35,470,648 | |

The 1998 Census of Pakistan indicated a population of 30.4 million, the current population in 2009 is 51,337,129 using a compound growth in the range of 2% to 2.8% since then. With just under half being urban dwellers, mainly found in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Mirpurkhas, Nawabshah District, Umerkot and Larkana. Sindhi is the sole official language of Sindh since the 19th century. According to the 2008 Pakistan Statistical Year Book,[1] Sindhi-speaking households make up 59.7% of Sindh's population; Urdu-speaking households make up 21.1%; Punjabi 7.0%; Pashto 4.2%; Balochi 2.1%; Saraiki 1.0% and other languages 4.9%. Other languages include Gujarati, Memoni, Kutchi (both dialects of Sindhi), Khowar, Thari, Persian/Dari and Brahui.

Sindh's population is mainly Muslim (91.32%), and Sindh is also home to nearly all (93%) of Pakistan's Hindus forming 7.5% of the province's population. A large number of Hindus migrated to India during Partition and were replaced by Muslim refugees known as Muhajirs who settled in Sindh. The Muhajirs migrated from different parts of India the majority of them spoke Urdu. Smaller groups of Christians (0.97%), Ahmadi (0.14%); Parsis or Zoroastrians, Armenian, Sikh and a Jewish community can also be found in the province.

The Sindhis as a whole are composed of original descendants of an ancient population known as Sammaat, various sub-groups related to the Seraiki or Baloch origin are found in interior Sindh. Sindhis of Balochi origin make up about 60% of the total population of Sindh, while Urdu-speaking Muhajirs make up more than 20% of the total population of the province. Also found in the province is a small group claiming descent from early Muslim settlers including Arabs, and Persian.

History

Ancient history

Sindh's first known village settlements date as far back as 7,000 BCE. Permanent settlements at Mehrgarh to the west expanded into Sindh. This culture blossomed over several millennia and gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization around 3000 BCE. The Indus Valley Civilization rivaled the contemporary civilizations of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in both size and scope numbering nearly half a million inhabitants at its height with well-planned grid cities and sewer systems.

Sindh was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the sixth century BCE. In the late 300s BCE, Sindh was conquered by a mixed army led by Macedonian Greeks under Alexander the Great. The region remained under control of Greek satraps only for a few decades. After Alexander's death, there was a brief period of Seleucid rule, before Sindh was traded to the Mauryan Empire led by Chandragupta in 305 BCE. During the rule of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist religion spread to Sindh.

Mauryan rule ended in 185 BCE with the overthrow of the last king by the Sunga Dynasty. In the disorders that followed, Greek rule returned when Demetrius I of Bactria led a Greco-Bactrian invasion of India and annexed most of northwestern lands, including Sindh. Demetrius was later defeated and killed by a usurper, but his descendants continued to rule Sindh and other lands as the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Under the reign of Menander I many Indo-Greeks followed his example and converted to Buddhism.

In the late 100s BCE, Scythian tribes shattered the Greco-Bactrian empire and invaded the Indo-Greek lands. Unable to take the Punjab region, they seized Sistan and invaded South Asia by coming through Sindh, where they became known as Indo-Scythians (later Western Satraps). Subsequently, the Tocharian Kushan Empire annexed Sindh by the first century CE. Though the Kushans were Zoroastrian, they were tolerant of the local Buddhist tradition and sponsored many building projects for local beliefs.

The Kushan Empire were defeated in the mid 200s CE by the Sassanid Empire of Persia, who installed vassals known as the Kushanshahs. These rulers were defeated by the Kidarites in the late 300s. By the late 400s, attacks by Hephthalite tribes known as the Indo-Hephthalites or Hunas (Huns) broke through the Gupta Empire's North-Western borders and overran much of Northern and Western India. During these upheavals, Sindh became independent under the Rai Dynasty around 478 AD. The Rais were overthrown by Chachar of Alor around 632.

Arrival of Islam

In 711 AD, Muhammad bin Qasim led a Umayyad force of 20,000 cavalry and 5 catapults, aided by Mokah Basayah, Thakore of Bhatta, Ibn Wasayo; Jat and Med tribes. Muhammad bin Qasim eventually defeated the Brahman Raja Dahir, and captured the cities of Alor, Multan and Debal. Large numbers of Sindhi tribes, Buddhists, Yogis and polytheists were converted to Islam.

Sindh became the easternmost province of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, referred to as "Al-Sindh" on Arab maps, with lands further east known as "Hind". Muhammad bin Qasim built the city of Mansura as his capital; the city then produced famous historical figures such as Abu Mashar Sindhi, Abu Ata Sindhi, Abul Hassan Sindhi, Abu Raja Sindhi, Sind ibn Ali and Mohammad Hayya Al-Sindhi. At the port city of Debal most of the Bawarij embraced Islam and became known as Sindhi Sailors; they became famous due to their skills in: navigation, geography and languages. In fact, they inspired the One Thousand and One Nights character Sindbad the Sailor[2] ("And thence we fared on to the land of Sind, where also we bought and sold"). By the year 750 AD, Debal was second only to Basra; Sindhi sailors from the port city of Debal voyaged to Basra, Bushehr, Musqat, Aden, Kilwa, Zanzibar, Sofala, Malabar, Sri Lanka and Java, where Sindhi merchants were known as the Santri.

In the year 725, Junayad Abbasi, the Abbasid Emir of Sindh, started an expedition from Nerun. He commanded a large army under the Abbasid flag, combining Arab and Sindhi Muslim cavalry. This army eventually destroyed the Hindu Brahman Temple of Somnath, and returned victoriously.

Muslim geographers, historians and travelers such as al-Masudi, Ibn Hawqal, Istakhri, Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi, al-Tabari, Baladhuri, al-Biruni, Saadi Shirazi, Ibn Battutah and Katip Çelebi[3] wrote about or visited the region, sometimes using the name "Sindh" for the entire area from the Arabian Sea to the Hindu Kush.

Soomro period

Direct Arab rule ended in 998 with the ascension of the local Soomra Dynasty, and they were the first local Sindhi Muslims to translate the Quran into the Sindhi language. The Soomros controlled Sindh directly as vassals the Abbasids from 1026 to 1351.

The Soomro's were one of the first Sindhi tribes to convert to Islam and they were known to the Arabs as the Al-Sumrah. They were taught Cavalry skills by the Arabs, and were renowned masters at riding the Arabian Horse and Camel, they created a network in Sindh which eventually facilitated their rule centered at Mansura. They often fought Hindu rebellions and raiders.

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, challenged the Soomra Dynasty and sieged their capital of Mansura, the city was conquered, little is known since then. However most of the Soomra became simple land owners and farmers some Soomra created forts such as Tharri and ruled as Amirs, nearly 14 km eastwards of Matli on the Puran. Puran was later abandoned due to changes in the course of Puran river they ruled for the next 95 years until the end of their rule in 1351 AD. During this period, Kutch was ruled by the Samma Dynasty, who enjoyed good relations with the Soomras in Sindh. The Soomros also produced many historical figures such as the brothers Dodo Bin Khafef Soomro III and Chenaser; and the Rano the Soomro prince in the Folk-story Mumal-Rano.

Sindh was also ruled by Muhammad Ibn Tughluq, his descendants and various other figures until the year 1524.

Samma period

Though a part of larger empires, Sindh enjoyed a certain autonomy as a Muslim domain.

In 1339 Jam Unar founded a Sindhi Muslim Samma Dynasty title of Sultan Of Sindh. His large forces from the south filled the political vacuum left behind after the collapse of the Soomro tribe. The Samma tribe reached its peak during the reign of Jam Nizamuddin II (also known by the nickname Jám Nindó). During his reign from 1461 to 1509, Nindó greatly expanded the new capital of Thatta and its Makli hills, which replaced Debal. He also patronized Sindhi art, architecture and culture. Important court figures included Sardar Darya Khan, Moltus Khan, Makhdoom Bilwal and Kazi Kazan. However, Thatta was a port city; unlike garrison towns, it could not mobilize large armies against the Arghun and Tarkhan Mongol invaders, who killed many regional Sindhi Mirs and Amirs loyal to the Samma.

The ruthless Arghuns and the Tarkhans sacked Thatta during the rule of Jam Ferozudin and established their own dynasties in the year 1519.

The Samma had left behind a popular legacy; they were highly influenced by the Lodis and introduced the Pashto alphabets to Sindh, some of which are still used in the Malay language of Southeast Asia.

Mughal period

In the year 1524 the few remaining Sindhi Amirs welcomed the Mughal Empire and helped Babur defeat his Arghun enemies. Sindh became a region fiercely loyal to the Mughals. A network of forts manned by cavalry and musketeers further extended Mughal power in Sindh.[4][5]

In 1540 a deadly mutiny by Sher Shah Suri forced the Mughal Emperor Humayun to withdraw to Sindh, where he joined the Sindhi Amir Hussein. In 1541 Humayun married Hamida Banu Begum. She gave birth to the infant Akbar at Umarkot in the year 1542.

In 1556 the Ottoman Admiral Seydi Ali Reis visited Humayun; various regions of the South Asia including Sindh (Makran coast and the Mehran delta) are mentioned in his book Mirat ul Memalik. The Portuguese navigator Fernão Mendes Pinto claims that Sindhi sailors joined the Ottoman Admiral Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis on his expedetion to Aceh in 1565.[4][6]

During the reign of Akbar, the Mughal chronicler Abu'l-Fazl (1551–1602) was a descendant of a Sindhi Shaikh family from Rel, Siwistan in Sindh. He became the author of Akbarnama (an official biographical account of Akbar) and the Ain-i-Akbari (a detailed document recording the administration of Akbar's empire).

In the year 1603 Shah Jahan visited the province of Sindh; at Thatta he was generously welcomed by the locals after the death of his father Jahangir. Shah Jahan ordered the construction of the Shahjahan Mosque, which was completed during the early years of his rule under the supervision of Mirza Ghazi Beg. Also during his reign, in the year 1659 (1070 AH) in Agra, the capital of the Mughal Empire, Muhammad Salih Tahtawi of Thatta created a seamless celestial globe with Arabic and Persian inscriptions using a wax casting method.[7][8]

After the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire and its institutions began to decline. Various warring Nawabs took control of vast territories; they ruled independently of the Mughal Emperor.

Meanwhile, Sindh faced many threats from the outside. Mian Yar Mouhammed Kalhoro (Khudabad) challenged the invader Nadir Shah but failed according to legend. To avenge the massacre of his allies he sent a small force to assassinate Nadir Shah and turn events in favor of the Mughal Emperor during the Battle of Karnal in 1739; this plot failed as well.

British period

The British East India Company made its first contacts in the Sindhi port city of Thatta, which according to a report was: "a city as large as London containing 50,000 houses which were made of stone and mortar with large verandahs some three or four stories high the...the city has 3000 looms...the textiles of Sind were the flower of the whole produce of the East, the international commerce of Sind gave it a place among that of Nations, Thatta has 400 schools and 4,000 Dhows at its docks, the city is guarded by well armed Sepoys..."

British and Bengal Presidency forces under General Charles James Napier arrived in Sindh in the nineteenth century and conquered Sindh in 1843. The Sindhi coalition led by Talpurs and Kalhoras under the Sindhi general Mir Nasir Khan Talpur were defeated in the Battle of Miani, during which 50,000 Sindhis were killed. Shortly afterward, Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur commanded another army at the Battle of Dubbo, where the young Sindhi general Hoshu Sheedi and 5,000 Sindhis were killed. The first Agha Khan helped the British in their conquest of Sindh, and as result he was granted a lifetime pension. The British East India Company conquered Karachi on February 3, 1839 and started developing it as a major port town.

A British Journal mentions the captive Sindhi Amirs held in Burma: "The Amirs as being the prisoners of "Her Majesty"... they are maintained in strict seclusion; they are described as Broken-Hearted and Miserable men, maintaining much of the dignity of fallen greatness, and without any querulous or angry complaining at this unlivable source of sorrow, refusing to be comforted"

Within weeks, Charles Napier and his forces occupied Sindh. After 1853, the British divided Sindh into districts. In each district they assigned a ruthless wadera to collect taxes for the British authorities. Wealthy businesses owned by Sindhi Muslim merchants were handed over to the minority Hindu Brahmans, leading the province to further unrest and a severe economic depression. Many Sindhi landowners had to take loans with high interest rates from Banias, money lenders who flocked to Sindh, and later many Sindhi landowners lost their land because they could not pay these loans.

In a highly controversial move, Sindh was later made part of British India's Bombay Presidency—much to the surprise of the local population, who found the decision offensive. A powerful unrest followed, after which Twelve Martial Laws were imposed by the British authorities. Shortly afterwards, the decision was reversed and Sindh became a separate province in 1935.

Sibghatullah Shah Rashidi pioneered the Hur Freedom Movement against British colonialists. He was hanged by the British rulers on 20 March 1943 in the Central Jail Hyderabad, Sindh. His burial place is not known and is still a mystery. The people of Sindh have been demanding the British government to disclose his burial place; however, so far this demand has not received any attention.

Pakistan Resolution in the Sindh Assembly

The Sindh assembly was the first British Indian legislature to pass the resolution in favour of Pakistan.

The Sindh assembly was the first British Indian legislature to pass the resolution in favour of Pakistan. G. M. Syed, an influential Sindhi activist, revolutionary and Sufi and one of the important leaders to the forefront of the provincial autonomy movement joined the Muslim League in 1938 and presented the Pakistan resolution in the Sindh Assembly. G. M. Syed can rightly be considered as the founder of Sindhi nationalism.

In 1890 Sindh got representation for the first time in the Bombay Legislative Assembly. Four members represented Sindh at that time. After some struggle, and with the support of the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Sindh gained independence from the Bombay Presidency. H.H. Sir Agha Khan, G.M. Syed, Sir Abdul Qayyum Khan and other Indian Muslim leaders played an important role in ensuring separation of Sindh from the Bombay Presidency, which finally took place on 1 April 1936.

The newly created province, Sindh, secured a Legislative Assembly of its own, elected on the basis of communal and minorities’ representation. Sir Lancelot Graham was appointed as the first Governor of Sindh by the British Government on 1 April 1936. He was also the Head of the Council, which comprised 25 Members, including two advisors from the Bombay Council to administer the affairs of Sindh until 1937. The British ruled the area for a century. According to Richard Burton, Sindh was one of the most restive provinces during the British Raj and was home to many prominent Muslim leaders such as Muhammad Ali Jinnah who strove for greater Muslim autonomy.

Independence of Pakistan

On 14 August 1947, Pakistan gained independence from colonial British colonial rule. The province of Sindh attained self-rule for the first time since the defeat of Sindhi Talpur Amirs in the Battle of Miani on 17 February 1843. The first challenge faced by the Government of Sindh was the settlement of Muslim refugees. Nearly 7 million Muslims from India migrated to Pakistan while a nearly equal number of Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan migrated to India. The Muslim refugees known as Muhajirs from India settled in most urban areas of Sindh. Sindh did not witness any massive rioting (as did the Punjab region and other areas of the subcontinent; there were comparatively few riots in Karachi and Hyderabad, and overall the situation remained peaceful.

Government

The Provincial Assembly of Sindh is unicameral and consists of 168 seats of which 5% are reserved for non-Muslims and 17% for women. The provincial capital of Sindh is Karachi.

The Sindh government was been presided by Chief Minister.

Most of the Sindhi tribes in the province are involved in Pakistan's politics. Sindh is a stronghold of the centre-left Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which is the largest political party in the province.

Districts

There are 23 districts in Sindh, Pakistan.[9]

Major cities

- Daharki

- Diplo

- Ghotki

- Dadu

- Hala

- Hyderabad

- Jacobabad

- Jamshoro

- Karachi

- Kashmore

- Khairpur

- Kotri

- Larkana

- Matli

- Mehar

- Mirpurkhas

- Mithi

- Mehrabpur

- Moro

- Nasarpur

- Nawabshah

- Naushahro Feroze (Padidan)

- Shahdadkot

- Raharki

- Ranipur

- Ratodero

- Sanghar

- Sehwan

- Sekhat

- Shikarpur

- Sobhodero

- Sukkur

- Rohri

- Tando Jam

- Tando Adam Khan

- Tando Muhammad Khan

- Thatta

- Ubaro

- Umarkot

Economy

Sindh has the 2nd largest economy in Pakistan. Historically, Sindh's contribution to Pakistan's GDP has been between 30% to 32.7%. Its share in the service sector has ranged from 21% to 27.8% and in the agriculture sector from 21.4% to 27.7%. Performance wise, its best sector is the manufacturing sector, where its share has ranged from 36.7% to 46.5%.[10] Since 1972, Sindh's GDP has expanded by 3.6 times.[11]

Endowed with coastal access, Sindh is a major centre of economic activity in Pakistan and has a highly diversified economy ranging from heavy industry and finance centred in and around Karachi to a substantial agricultural base along the Indus. Manufacturing includes machine products, cement, plastics, and various other goods.

Agriculture is very important in Sindh with cotton, rice, wheat, sugar cane, bananas, and mangoes as the most important crops. Sindh is the richest province in natural resources of gas, petrol, and coal.

Education

| Year | Literacy rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 30.2% |

| 1981 | 31.5% |

| 1998 | 45.29% |

| 2008 | 57.7% |

This is a chart of the education market of Sindh estimated by the government in 1998.[14]

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrollment ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 14,839,862 | 15,600,031 | 30,439,893 | — |

| Below Primary | 1,984,089 | 3,332,166 | 5,316,255 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 3,503,691 | 5,687,771 | 9,191,462 | 82.53 |

| Middle | 3,073,335 | 2,369,644 | 5,442,979 | 52.33 |

| Matriculation | 2,847,769 | 2,227,684 | 5,075,453 | 34.45 |

| Intermediate | 1,473,598 | 1,018,682 | 2,492,280 | 17.78 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 106,847 | 53,040 | 159,887 | 9.59 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 1,320,747 | 552,241 | 1,872,988 | 9.07 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 440,743 | 280,800 | 721,543 | 2.91 |

| Other qualifications | 89,043 | 78,003 | 167,046 | 0.54 |

Major public and private educational institutes of Sindh include:

- Adamjee Government Science College

- Aga Khan University

- APIIT

- Applied Economics Research Centre

- Bahria University

- College of Digital Sciences

- College of Physicians & Surgeons Pakistan

- COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences

- D. J. Science College

- Dawood College of Engineering and Technology

- Defence Authority Degree College for Men

- Dow International Medical College

- Dow University of Health Sciences

- Fatima Jinnah Dental College

- Federal Urdu University

- Government College for Men Nazimabad

- Government College of Commerce & Economics

- Government College of Technology, Karachi

- Government Dehli College

- Government National College (Karachi)

- Greenwich University (Karachi)

- Hamdard University

- Hussain Ebrahim Jamal Research Institute of Chemistry

- Indus Valley Institute of Art and Architecture

- Institute of Business Administration, Karachi

- Institute of Business Management

- Institute of Industrial Electronics Engineering

- Institute of Sindhology

- Iqra University

- Islamia Science College (Karachi)

- Isra University

- Jinnah Medical & Dental College

- Jinnah Polytechnic Institute

- Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre

- Jinnah University for Women

- KANUPP Institute of Nuclear Power Engineering

- Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences

- Mehran University of Engineering and Technology

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah University

- National Academy of Performing Arts

- National University of Sciences and Technology

- NED University of Engineering and Technology

- Ojha Institute of Chest Diseases

- PAF Institute of Aviation Technology

- Pakistan Navy Engineering College

- Pakistan Shipowners' College

- Pakistan Steel Cadet College

- Peoples Medical Girls College Nawabshah

- Provincial Institute of Teachers Education Nawabshah

- Quaid-e-Awam University of Engineering, Sciences and Technology, Nawabshah

- Rana Liaquat Ali Khan Government College of Home Economics

- Rehan College of Education

- Saint Patrick's College, Karachi

- Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai University

- Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology

- Sindh Agriculture University

- Sindh Medical College

- Superior College of Science Hyderabad

- Sindh Muslim Law College

- Sir Syed Government Girls College

- Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology

- St. Joseph's College

- Textile Institute Of Pakistan

- University of Karachi

- University of Sindh

- Usman Institute of Technology

- Ziauddin Medical University

-

Sindh Madarsat-ul-Islam, 1893

-

Sindh Agriculture University

Admissions to state-run educational institutions in Pakistan are based on the provincial level. Pakistan's other three provinces have a policy of merit-based intraprovincial admissions to state-run educational institutes. Sindh is an exception to this general rule; here admissions are determined by the district domiciles of the candidates and their parents. Critics of this controversial arrangement say that it discriminates against meritorious students of Sindhi ethnic background, denying them admission to the educational institutes and courses of their choice.

The armed forces have also entered the education sector in Sindh. They are funded by the government and operate like private costly education providers.

Arts and crafts

The traditions of Sindhi craftwork reflect the cumulative influence of 5000 years of invaders and settlers, whose various modes of art were eventually assimilated into the culture. The elegant floral and geometrical designs that decorate everyday objects—whether of clay, metal, wood, stone or fabric—can be traced to Muslim influence.

Though chiefly an agricultural and pastoral province, Sindh has a reputation for ajraks, pottery, leatherwork, carpets, textiles, and silk cloths which, in design and finish, are matchless. The chief articles produced are blankets, coarse cotton cloth (soosi), camel fittings, metalwork, lacquered work, enamel, gold and silver embroidery. Hala is famous for pottery and tiles; Boobak for carpets; Nasirpur, Gambat and Thatta for cotton lungees and khes. Other popular crafts include the earthenware of Johi, the metal vessels of Shikarpur, the relli, embroidery and leather articles of Tharparkar, and the lacquered work of Kandhkot.

Prehistoric finds from archaeological sites like Mohenjo-daro, engravings in various graveyards, and the architectural designs of Makli and other tombs have provided ample evidence of the people's literary and musical traditions.

Modern painting and calligraphy have also developed in recent times. Some young trained men have taken up commercial art.

Cultural heritage

Sindh has a rich heritage of traditional handicraft that has evolved over the centuries. Perhaps the most professed exposition of Sindhi culture is in the handicrafts of Hala, a town some 30 kilometres from Hyderabad. Hala’s artisans manufacture high-quality and impressively priced wooden handicrafts, textiles, paintings, handmade paper products, and blue pottery. Lacquered wood works known as Jandi, painting on wood, tiles, and pottery known as Kashi, hand woven textiles including khadi, susi, and ajraks are synonymous with Sindhi culture preserved in Hala’s handicraft.

The Small and Medium Enterprises Authority (SMEDA) is planning to set up an organization of artisans to empower the community. SMEDA is also publishing a directory of the artisans so that exporters can directly contact them. Hala is the home of a remarkable variety of traditional crafts and traditional handicrafts that carry with them centuries of skill that has woven magic into the motifs and designs used.[citation needed]

Sindh is known the world over for its various handicrafts and arts. The work of Sindhi artisans was sold in ancient markets of Armenia, Baghdad, Basra, Istanbul, Cairo and Samarkand. Referring to the lacquer work on wood locally known as Jandi, T. Posten (an English traveller who visited Sindh in the early 19th century) asserted that the articles of Hala could be compared with exquisite specimens of China.[citation needed] Technological improvements such as the spinning wheel (charkha) and treadle (pai-chah) in the weaver's loom were gradually introduced and the processes of designing, dyeing and printing by block were refined. The refined, lightweight, colourful, washable fabrics from Hala became a luxury for people used to the woolens and linens of the age.

The ajrak has existed in Sindh since the birth of its civilization. The colour blue is predominantly used for ajraks. Sindh was traditionally a large producer of indigo and cotton cloth and both used to be exported to the Middle East. The ajrak is a mark of respect when it is given to an honoured guest or friend. In Sindh, it is most commonly given as a gift at Eid, at weddings, or on other special occasions like homecoming.

The Rilli, or patchwork quilt, is another Sindhi icon and part of the heritage and culture. Most Sindhi homes have a set of Rillis—one for each member of the family and a few spare for guests. The Rilli is made with small pieces of cloth of different geometrical shapes sewn together to create intricate designs. They may be used as a bedspread or a blanket, and are often given as gifts to friends and guests.

Many women in rural Sindh are skilled in the production of caps. Sindhi caps are manufactured commercially on a small scale at New Saeedabad and Hala New. These are in demand with visitors from Karachi and other places; however, these manufacturing units have a limited production capacity.

Sindhi people began celebrating Sindhi Topi Day on December 6, 2009 to preserve the historical culture of Sindh by wearing Ajrak and Sindhi topi.[15]

-

Mir Muhammad Naseer Khan Talpur, the last ruler of Sindh -

The great Pakistani Sufi singer, Abida Parveen, visited Oslo in September 2007. -

Huts in the Thar desert

The Sindhi language

Sindhī (Arabic script: سنڌي, Devanagari script: सिन्धी) is spoken by about 15 million people in the province of Sindh. The largest Sindhi-speaking city is Hyderabad, Pakistan. It is an Indo-European language, related to Kutchi, Gujarati and other Indo-European languages prevalent in the region with substantial Persian, Turkish and Arabic loan words. In Pakistan it is written in a modified Arabic script.

Key dialects: Kachchi, Lari, Lasi, Thareli, Vicholo (Central Sindhi), Macharia, Dukslinu (Hindu Sindhi), and Sindhi Musalmani (Muslim Sindhi).

Places of interest

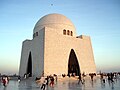

Sindh has numerous tourist sites, the most notable being the ruins of Mohenjo-daro near the city of Larkana. Islamic architecture is quite prominent in the province; numerous mausoleums dot the province, including the very old Shahbaz Qalander mausoleum dedicated to the Iranian-born Sufi, and the beautiful mausoleum of Muhammad Ali Jinnah (known as the Mazar-e-Quaid) in Karachi. Also of note is the Jama Masjid in Thatta, built by the Mughal emperor Shahjahan.

- Aror (ruins of historical city) near Sukkur

- Chaukandi Tombs, Karachi

- Forts at Hyderabad and Umarkot

- Gorakh Hill in Dadu

- Kahu-Jo-Darro near Mirpurkhas

- Kot Diji Fort, Kot Diji

- Kotri Barrage near Hyderabad

- Makli Hill, Asia's largest necropolis, Makli, Thatta

- Mazar-e-Quaid, Karachi

- Minar-e-Mir Masum Shah, Sukkur

- Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi

- Rani Bagh, Hyderabad

- Ranikot Fort near Sann

- Ruins of Mohenjo-daro & Museum near Larkana

- Pakka Qill Hyderabad

- Sadhu Bela Temple near Sukkur

- Shahjahan Mosque, Thatta

- Shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Bhit Shah

- Shrine of Shahbaz Qalander in Sehwan Shairf, Dadu

- Sukkur Barrage, Sukkur

- Talpurs' Faiz Mahal Palace, Khairpur

-

Faiz Mahal, Khairpur

-

Ranikot Fort, one of the largest forts in the world

-

Tomb of M.A. Jinnah in Karachi

-

Karachi Beach

-

Keenjhar lake Thatta

-

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro

-

West bank of the River Indus

-

Bakri Waro Lake, Khairpur

-

Peninsula of Manora

-

Bhutto family Mausoleum

See also

- Ba'ab-ul-Islam

- List of Sindhi people

- Harappa

- Institute of Sindhology

- Karachi

- Mohenjodaro

- Sateen Jo Aastan

- Sindhudesh

References

- ^ "Percentage Distribution of Households by Language Usually Spoken and Region/Province, 1998 Census." Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2008. Federal Bureau of Statistics - Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/arabian/bl-arabian-3sindbad.htm

- ^ http://www.muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?articleID=1137

- ^ a b The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p.39

- ^ Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492-1792 by Jeremy Black p.16 [1]

- ^ http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/01475176655936417554480/p0000002.htm Cervantes Virtual website

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Kazi, Najma (24 November 2007). "Seeking Seamless Scientific Wonders: Review of Emilie Savage-Smith's Work". FSTC Limited. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ District Nazims of the Province of Sindh

- ^ Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973-2000

- ^ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PAKISTANEXTN/Resources/293051-1241610364594/6097548-1257441952102/balochistaneconomicreportvol2.pdf

- ^ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001459/145959e.pdf

- ^ http://www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/fbs/publications/lfs2007_08/results.pdf

- ^ "Population by Level of Education and Rural/Urban". Statistics Division: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics. Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ Sindh celebrates first ever ‘Sindhi Topi Day’

Further reading

- Malkani, Kewal Ram (1984). The Sindh Story. Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

External links