International Military Tribunal for the Far East

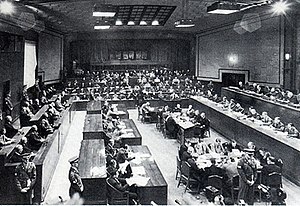

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trials, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal or simply as the Tribunal, was convened on May 5, 1946 to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for three types of crimes: "Class A" (crimes against peace), "Class B" (war crimes), and "Class C" (crimes against humanity), committed during World War II. The first refers to their joint conspiracy to start and wage the war, and the latter two refer to atrocities, one of the most notorious of these being the Nanking Massacre.

The Tokyo trials were not the only forum for the punishment of Japanese war criminals, merely the most visible. In fact, the Asian countries victimized by the Japanese war machine tried far more Japanese—an estimated five thousand, executing as many as 900 and sentencing more than half to life in prison.

Twenty-eight Japanese military and political leaders were charged with Class A crimes, and more than 5,700 Japanese nationals were charged with Class B and C crimes, mostly entailing prisoner abuse. China held 13 tribunals of its own, resulting in 504 convictions and 149 executions.

The Japanese Emperor Hirohito, and all members of the imperial family such as Prince Asaka, were not prosecuted for any involvement in any of the three categories of crimes. As many as 50 suspects, such as Nobusuke Kishi, who later became Prime Minister, and Yoshisuke Aikawa, head of the zaibatsu Nissan, and future leader of the Chuseiren, were charged but released without ever being brought to trial in 1947 and 1948. Shiro Ishii received immunity in exchange for data gathered from his experiments on live prisoners.

The tribunal was adjourned on November 12, 1948.

Background

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration, the Instrument of Surrender and the Moscow Conference. The Potsdam declaration had called for trials and purges of those who had "deceived and misled" the Japanese people into war. However, there was major disagreement, both among the Allies and within the U.S., about whom to try and how to try them. Despite the lack of consensus, General Douglas MacArthur - the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers - decided to initiate arrests. On September 11, just over a week after the surrender, he ordered the arrest of thirty-nine suspects — most of them members of General Tojo's war cabinet. Perhaps caught off guard, Tojo tried to committ suicide, but was resuscitated with the help of American doctors.

Creation of the court

On 19 January 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter followed generally the model set by the Nuremberg Trials. On 25 April 1946 in accordance with the provisions of Article 7 of the CIMTFE the original Rules of Procedure of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East with amendments were promulgated. [1][2][3]

Judges

MacArthur appointed a panel of eleven judges, nine from the nations that signed the Instrument of Surrender.

Prosecutors

The chief prosecutor, Joseph B. Keenan of the USA, was appointed by President Truman.

| Country | Prosecutor | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Chief Prosecutor (USA) | Joseph Keenan | U.S. Asst. Attorney General Director of the Criminal Division of the U.S. Dept. of Justice |

| Australia | Mr. Justice Alan Mansfield | Senior Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland |

| Canada | Brigadier Henry Nolan | Vice-Judge Advocate General of the Canadian Army |

| Republic of China | Xiang Zhejun (Hsiang Che-chun) | Minister of Justice and Foreign Affairs |

| Provisional Government of the French Republic | Robert L. Oneto | |

| British India | P. Govinda Menon | |

| Netherlands | W.G. Frederick Borgerhoff-Mulder | |

| New Zealand | Brigadier Ronald Henry Quilliam | Deputy Adjutant-General of the New Zealand Army |

| Philippines | Pedro Lopez | Associate Prosecutor of the Philippines |

| UK | Arthur Strettell Comyns Carr | British MP and Barrister |

| USSR | Minister and Judge Sergei Alexandrovich Golunsky |

Defendants

28 defendants were charged, mostly military officers and government officials.

Government officials

- Matsuoka Yosuke, Foreign Minister (1940–1941)

- Baron Kōki Hirota, prime minister (1936–1937), Foreign Minister (1933–1934, 1937–1938)

- General Seishirō Itagaki, war minister

- General Sadao Araki, war minister

- Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, war minister

- Baron Kiichirō Hiranuma, prime minister

- Naoki Hoshino, Chief Cabinet Secretary

- Marquis Kōichi Kido, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

- General Kuniaki Koiso, governor of Korea, later prime minister

- Admiral Takasumi Oka, naval minister

- General Hiroshi Ōshima, ambassador to Germany

- General Kenryō Satō, chief of the Military Affairs Bureau

- Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, naval minister

- Toshio Shiratori, ambassador to Italy

- General Teiichi Suzuki, president of the Cabinet Planning Board

- General Yoshijirō Umezu, war minister

- Foreign minister Shigenori Tōgō

- Foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu

- Finance minister Okinori Kaya

Military officers

- Nagano Osami, Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff (April 1941 to February 1944)

- General Kenji Doihara, Chief of the intelligence service in Manchukuo, later Air Force commander

- General Heitarō Kimura, commander, Burma Expeditionary Force

- General Iwane Matsui, commander, Shanghai Expeditionary Force and Central China Area Army

- General Akira Muto, commander, Philippines Expeditionary Force

- General Hideki Tōjō, commander, Kwantung Army (later prime minister)

- Colonel Kingorō Hashimoto, major instigator of the second Sino-Japanese War

- General Jirō Minami, commander, Kwantung Army

Other defendants

- Shūmei Ōkawa, a political philosopher

Tokyo War Crimes Trial

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE, also known as the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, first convened on April 29, 1946. As at Nuremberg, the location held a special irony. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3, the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with "Conventional War Crimes," "Crimes against Peace," and "Crimes against Humanity." The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses, and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

Charges

Following the model used at the Nuremberg Trials in Germany, the Allies established three broad categories. "Class A" charges alleging "crimes against peace" were to be brought against Japan's top leaders who had planned and directed the war. Class B and C charges, which could be leveled at Japanese of any rank, covered "conventional war crimes" and "crimes against humanity," respectively. However, unlike the Nuremberg Trials, the charge of crimes against peace was a prerequisite to prosecution, that is, only those individuals whose crimes included "crimes against peace" could be prosecuted by the Tribunal.

The indictment accused the defendants of promoting a scheme of conquest that "contemplated and carried out ... murdering, maiming and ill-treating prisoners of war (and) civilian internees ... forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions ... plundering public and private property, wantonly destroying cities, towns and villages beyond any justification of military necessity; (perpetrating) mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless civilian population of the over-run countries."

Joseph Keenan, the chief prosecutor representing the United States at the trial, issued a press statement along with the indictment: " war and treaty-breakers should be stripped of the glamour of national heroes and exposed as what they really are --- plain, ordinary murderers."

| Count | Offence |

|---|---|

| 1 | As leaders, organisers, instigators, or accomplices in the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy to wage wars of aggression, and war or wars in violation of international law. |

| 27 | Waging unprovoked war against China. |

| 29 | Waging aggressive war against the United States. |

| 31 | Waging aggressive war against the British Commonwealth. |

| 32 | Waging aggressive war against the Netherlands. |

| 33 | Waging aggressive war against France (Indochina). |

| 35,36 | Waging aggressive war against the USSR. |

| 54 | Ordered, authorised, and permitted inhumane treatment of Prisoners of War (POWs) and others. |

| 55 | Deliberately and recklessly disregarded their duty to take adequate steps to prevent atrocities. |

Evidence and testimony

The prosecution began opening statements on May 3, 1946, it took 192 days to present its case, finishing on January 24, 1947. The prosecution presented its evidence in fifteen phases. The Tokyo war crimes trials were a sharp contrast with the Nuremberg proceedings. Whereas the Nuremberg convictions were supported by masses of documentary evidence, the Japanese destroyed most of their military records at the time of their surrender. This made it exceedingly difficult for allied investigators to find evidence of criminal orders.

The evidentiary standard was greatly relaxed. The Charter provided that evidence against the accused could include any document "without proof of its issuance or signature" as well as diaries, letters, press reports and sworn or unsworn out of court statements relating to the charges.[4] Article 13 of the Charter read in part: "The tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence . . . and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value".[5].

War time press releases of the Allies were admitted as evidence by the prosecution while those sought to be entered by the defense were excluded.[6] The recollection of a conversation with a long-dead man was admitted (Ibid.). Letters allegedly written by Japanese citizens were admitted with no proof of authenticity and no opportunity for cross examination by the defense (Ibid.).

Finally, the Tribunal embraced the "Best Evidence Rule" once the Prosecution had rested .[7] The "Best Evidence Rule" dictates that the "best" or most authentic evidence must be produced (e.g., a map instead of a description of the map; an original instead of a copy; and, a witness instead of a description of what the witness may have said). Justice Pal, one of two justices to vote for acquittal on all counts, observed, "in a proceeding where we had to allow the prosecution to bring in any amount of hearsay evidence, it was somewhat misplaced caution to introduce this best evidence rule particularly when it operated practically against the defense only . . .".[7]

To prove their case, the prosecution team relied on the doctrine of "command responsibility" instead. The advantage of this doctrine was that it didn't require proof of criminal orders. The prosecution had to prove three things: that war crimes were systematic or widespread; the accused knew that troops were committing atrocities; and the accused had power or authority to stop the crimes.

The prosecution argued that a 1927 document known as the Tanaka Memorial showed that a "Common Plan or Conspiracy" to commit "Crimes against Peace" bound the accused together. Thus, the prosecution argued that the conspiracy had begun in 1927 and continued through to the end of the Asia and Pacific War in 1945. The Tanaka Memorial is now considered by most historians to have been a forgery; however, it was not regarded as such at the time.

Defense

The defendants were represented by over one hundred attorneys, three-quarters Japanese and one-quarter American, plus a support staff of their own. The defense opened its case on January 27, 1947, and finished its presentation 225 days later.

The defense argued that the trial could never be "free from substantial doubt as to its "legality, fairness and impartiality".[8]

The defense challenged the indictment, arguing that ‘crimes against peace’ and more specifically, the undefined concepts of ‘conspiracy’ and ‘aggressive war’, had yet to be established as crimes in international law; in effect, the IMTFE was contradicting accepted legal procedure by trying the defendants retroactively for violating laws which had not existed when these alleged crimes had been committed. Moreover, the defence insisted that there was no basis in international law for holding individuals responsible for acts of state, as the Tokyo trial proposed to do. The defense further attacked the notion of ‘negative criminality’, by which the defendants were to be tried for failing to prevent breaches of law and war crimes by others, as likewise having no basis in international law.

The defense argued that Allied Powers' violations of international law, including the atomic bombings of Japan, should be examined. The tribunal ignored this argument and thus left the door open for later criticism that the trials had merely carried out "victors' justice."

Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo maintained that Japan had had no choice but to enter the war for self-defense purposes. He asserted that "[because of the Hull Note] we felt at the time that Japan was being driven either to war or suicide.".

Judgment

The IMT spent six months reaching judgment and drafting its 1,781-page opinion.

On the day the judgment was read, five of the eleven justices released separate opinions outside the court.

In his concurring opinion Justice Webb (Australia) took issue with Emperor Hirohito's legal status. "The suggestion that the Emperor was bound to act on advice is contrary to the evidence," wrote Webb. While refraining from personal indictment of Hirohito, Webb indicated that Hirohito bore responsibility as a Constitutional Monarch who accepted "ministerial and other advice for war" and that "no ruler can commit the crime of launching aggressive war and then validly claim to be excused for doing so because his life would otherwise have been in danger … It will remain that the men who advised the commission of a crime, if it be one, are in no worse position than the man who directs the crime be committed"[9].

Justice Jaranilla (Philippines) disagreed with the penalties imposed by the tribunal. "They are, in my judgment, too lenient," wrote the justice, "not exemplary and deterrent, and not commensurate with the gravity of the offence or offences committed."

Justice Henri Bernard (France) pointed out the tribunal's flawed course of action such as the absence of Hirohito and the lack of sufficient deliberations by the judges. He concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices".[10] and that "A verdict reached by a Tribunal after a defective procedure cannot be a valid one)(...)".

"It is well-nigh impossible to define the concept of initiating or waging a war of aggression both accurately and comprehensively," wrote Justice B. V. A. Röling (Netherlands) in his dissenting opinion.

Justice Roling stated "I think that not only should there have been neutrals in the court, but there should have been Japanese also." He also argued that they would always have been a minority and therefore, would not have been able to sway the balance of the trial, however, "they could have convincingly argued issues of government policy which were unfamiliar to the Allied justices". Pointing out the difficulties and limitations in holding individuals responsible for an act of state, and making omission of responsibility a crime, Röling called for the acquittal of several defendants including Hirota.

Justice Radhabinod Pal (India) produced a 1,235-page judgment in which he dismissed the legitimacy of the IMTFE as mere victor's justice. "I would hold that each and every one of the accused must be found not guilty of each and every one of the charges in the indictment and should be acquitted on all those charges," concluded Pal. Pal did not question whether the Japanese military had committed atrocities during the war. While taking into account the influence of wartime propaganda, exaggerations and distortions of facts in the evidence, and "over-zealous" and "hostile" witnesses, Pal concluded, "The evidence is still overwhelming that atrocities were perpetrated by the members of the Japanese armed forces against the civilian population of some of the territories occupied by them as also against the prisoners of war."

Sentencing

Two defendants (Matsuoka Yosuke and Nagano Osami) had died of natural causes during the trial.

Six defendants were sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes against peace (Class A, Class B and Class C):

- General Kenji Doihara, Chief of the intelligence service in Manchukuo, later Air Force commander

- Baron Kōki Hirota, foreign minister

- General Seishirō Itagaki, war minister

- General Heitarō Kimura, commander, Burma Expeditionary Force

- General Akira Muto, commander, Philippines Expeditionary Force

- General Hideki Tōjō, commander, Kwantung Army (later prime minister)

One defendant was sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes and crimes against humanity (Class B and Class C):

- General Iwane Matsui, commander, Shanghai Expeditionary Force and Central China Area Army

They were executed at Sugamo Prison in Ikebukuro on December 23, 1948. MacArthur, afraid of embarrassing and antagonizing the Japanese people, defied the wishes of President Truman and barred photography of any kind, instead bringing in four members of the Allied Council to act as official witnesses.

Sixteen more were sentenced to life imprisonment. Three (Koiso, Shiratori, and Umezu) died in prison, while the other thirteen were paroled between 1954 and 1956:

- General Sadao Araki, war minister

- Colonel Kingorō Hashimoto, major instigator of the second Sino-Japanese War

- Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, war minister

- Baron Kiichirō Hiranuma, prime minister

- Naoki Hoshino, Chief Cabinet Secretary

- Okinori Kaya, finance minister

- Marquis Kōichi Kido, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

- General Kuniaki Koiso, governor of Korea, later prime minister

- General Jirō Minami, commander, Kwantung Army

- Admiral Takasumi Oka, naval minister

- General Hiroshi Ōshima, ambassador to Germany

- General Kenryō Satō, chief of the Military Affairs Bureau

- Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, naval minister

- Toshio Shiratori, ambassador to Italy

- General Teiichi Suzuki, president of the Cabinet Planning Board

- General Yoshijirō Umezu, war minister

Foreign minister Shigenori Tōgō was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment and died in prison in 1949. Foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu was sentenced to 7 years.

The verdict and sentences of the tribunal were confirmed by General MacArthur on November 24, 1948, two days after a perfunctory meeting with members of the Allied Control Commission for Japan, who acted as the local representatives of the nations of the Far Eastern Commission set up by their governments. Six of those representatives made no recommendations for clemency. Australia, Canada, India, and the Netherlands were willing to see the general make some reductions in sentences. He chose not to do so. The issue of clemency was thereafter to disturb Japanese relations with the Allied powers until the late 1950s when a majority of the Allied powers agreed to release the last of the convicted major war criminals from captivity.

Criticism

According to Japanese tabulation, 5,700 Japanese individuals were indicted for Class B and Class C war crimes. Of this number, 984 were initially condemned to death; 475 received life sentences; 2,944 were given more limited prison terms; 1,018 were acquitted and 279 were never brought to trial or not sentenced. The number of death sentences by country is the following : Holland 236, Great Britain 223, Australia 153, China 149, USA 140, France 26 and Philippines 17.[11] Additionally, the Soviet Union and Chinese Communist forces held trials for Japanese war criminals.

The Khabarovsk War Crime Trials held by the Soviets tried and found guilty some members of Japan's bacteriological and chemical warfare unit (Unit 731). However those who surrendered to the Americans were never brought to trial as MacArthur secretly granted immunity to the physicians of Unit 731 in exchange for providing America with their research on biological weapons. On 6 May 1947, MacArthur wrote to Washington that "additional data, possibly some statements from Ishii probably can be obtained by informing Japanese involved that information will be retained in intelligence channels and will not be employed as 'War Crimes' evidence." [12] The deal was concluded in 1948.[13]

One of the focuses of the Tribunal was crimes against peace, but Gen. MacArthur himself after retirement on May 3, 1951 in the Senate Armed Services Committee stated, "They (Japanese) feared that if those supplies were cut off, there would be 10 to 12 million people unoccupied in Japan. Their purpose, therefore, in going to war was largely dictated by security." [14]

Fairness

1. The tribunals had not held based on the international laws in the first place.

2. The laws made after the fact used in this tribunals.

3. The crimes on peace/humanity & POWs commited by allies did not judged. (equality under the laws.)

Composition of prosecution team

It is also argued by some, such as Solis Horowitz, that IMTFE had an American bias, because unlike the Nuremberg Trials, there was only a single prosecution team, which was led by Joseph B. Keenan, an American, although the members of the tribunal represented eleven different Allied countries.[15]

The IMTFE had less official support than the Nuremberg Trials. For example, Keenan, a former US assistant attorney general, had a much lower position than Nuremberg's Robert H. Jackson, a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Charges of victors' justice

Because the United States had provided the funds and the staff necessary for the running of the Tribunal and also held the function of Chief Prosecutor, there were some who argued that it was difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile these different elements with the requirement of impartiality with which such an organ should be invested. This apparent conflict gave the impression that the tribunal was no more than a means for the dispensation of victor’s justice.

Justice Radhabinod Pal, the Indian justice at the IMTFE, argued that the exclusion of Western colonialism and the use of the atom bomb by the United States from the list of crimes, and judges from the vanquished nations on the bench, signified the "failure of the Tribunal to provide anything other than the opportunity for the victors to retaliate." [16] In this he was not alone among Indian jurists of the time, one prominent Calcutta barrister writing that the Tribunal was little more than "a sword in a [judge's] wig".

Justice B. V. A. Roling stated, "[o]f course, in Japan we were all aware of the bombings and the burnings of Tokyo and Yokohama and other big cities. It was horrible that we went there for the purpose of vindicating the laws of war, and yet saw every day how the Allies had violated them dreadfully".

Pal's dissenting opinion

Pal's dissenting opinion also raised substantive objections: he found that the entire prosecution case, that there was a conspiracy to commit an act of aggressive war, which would include the brutalization and subjugation of conquered nations, weak. About the Rape of Nanking in particular, he said, after acknowledging the brutality of the incident (and that the "evidence was overwhelming" that "atrocities were perpetrated by the members of the Japanese armed forces against the civilian population... and prisoners of war"), that there was nothing to show that it was the "product of government policy", and thus that the officials of the Japanese government were directly responsible. Indeed, he said, there is "no evidence, testimonial or circumstantial, concomitant, prospectant, restrospectant, that would in any way lead to the inference that the government in any way permitted the commission of such offenses." [16]

In any case, he added, conspiracy to wage aggressive war was not illegal in 1937, or at any point since.[16]

Exoneration of the imperial family

There has been much criticism of the blanket exoneration of Emperor Showa and all members of the imperial family implicated in the war such as Prince Asaka, Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, Prince Higashikuni and Prince Takeda[17][18].

-

Emperor Showa

-

Prince Yasuhiko Asaka

-

Prince Hiroyasu Fushimi

-

Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni

-

Prince Tsuneyoshi Takeda

As early as 26 November 1945, MacArthur confirmed to Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai that the emperor's abdication would not be necessary.[19] Before the war crimes trials actually convened, SCAP, the IPS and court officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the emperor. High officials in court circles and the Japanese government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the individuals arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in the Sugamo Prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.[19]

According to Herbert Bix, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers "immediately on landing in Japan went to work to protect Hirohito from the role he had played during and at the end of the war" and "allowed the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the emperor would be spared from indictment." [20]

Bix also argues that "MacArthur's truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact on Japanese understanding of the lost war" and "months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor to Hideki Tōjō." [21] According to the written report of Shūichi Mizota, the interpreter of admiral Mitsumasa Yonai, Fellers met the two men at his office on March 6, 1946 and told Yonai, "it would be most convenient if the Japanese side could prove to us that the emperor is completely blameless. I think the forthcoming trials offer the best opportunity to do that. Tōjō, in particular, should be made to bear all responsibility at this trial"[22][23].

For John W. Dower, "This successful campaign to absolve the emperor of war responsibility knew no bounds. Hirohito was not merely presented as being innocent of any formal acts that might make him culpable to indictment as a war criminal. He was turned into an almost saintly figure who did not even bear moral responsibility for the war", "With the full support of MacArthur's headquarters, the prosecution functioned, in effect, as a defense team for the emperor"[19] and "Even Japanese activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters, and who have labored to document and publicize the atrocities of the Shōwa regime, cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of the Cold war, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-winged war criminals like the later prime minister Nobusuke Kishi"[24]

Three judges wrote an obiter dictum about the criminal responsibility of Hirohito. Judge-in-Chief Webb declared, "no ruler can commit the crime of launching aggressive war and then validly claim to be excused for doing so because his life would otherwise have been in danger … It will remain that the men who advised the commission of a crime, if it be one, are in no worse position than the man who directs the crime be committed"[9].

Judge Henri Bernard of France concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices"[25].

For judge B. V. A. Röling however, nothing objectable could be found in the Emperor's immunity and five defendants (Kido, Hata, Hirota, Shigemitsu and Tōgō) should have been acquitted.

Immunity granted for germ warfare experiments

As Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, MacArthur also gave immunity to Shiro Ishii and all members of the bacteriological research units in exchange for germ warfare data based on human experimentation. On May 6, 1947, he wrote to Washington that "additional data, possibly some statements from Ishii probably can be obtained by informing Japanese involved that information will be retained in intelligence channels and will not be employed as "War Crimes" evidence."[12] The deal was concluded in 1948.[13]

In 1981, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published an article by John W. Powell detailing Unit 731 experiments and germ warfare open-air tests on civilian populations. It was printed with a statement by judge B. V. A. Röling, the last surviving member of the Tokyo Tribunal. Röling wrote that "As one of the judges in the International Military Tribunal, it is a bitter experience for me to be informed now that centrally ordered Japanese war criminality of the most disgusting kind was kept secret from the Court by the U.S. government." [26]

Aftermath

Release of the remaining 42 "Class A" war criminals

The International Prosecution Section of the SCAP decided to try the seventy Japanese apprehended as "Class A" war criminals in three groups, the first group of 28 all being major leaders in the military, political, and diplomatic sphere. The 2nd group of 23 war criminals and the 3rd group of 19 war criminals were notorious, industrial and financial magnates, who were engaged in ammunition trade and trafficking in drugs, as well as some lesser known leaders in military, political, and diplomatic spheres. The most notable among these were:

- Nobusuke Kishi: In charge of industry and commerce of Manchukuo, 1936–40; Minister of Industry and Commerce under Tojo administration. Prime Minister of Japan postwar.

- Fusanosuke Kuhara: Leader of the newly-emerging Zaibatsu faction of Seiyukal (Political Friends Society).

- Yoshisuke Ayukawa: Sworn-brother of Fusanosuke Kuhara, founder of Japan Industrial Corporation; went to Manchuria after the "September 18" Incident, where he founded the Manchurian Heavy Industry Development Company

- Toshizo Nishio: Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army, Commander-in-Chief of China Expeditionary Army, 1939–41; and Minister of Education.

- Kichiburo Ando: Garrison Commander of Port Arthur and Minister of Interior in Tojo's cabinet.

- Yoshio Kodama: Radical ultranationalist

- Kazuo Aoki: Administrator of Manchurian affairs; Minister of Treasury in Nobuyoki Abe's cabinet and then following Abe to China as advisor; Minister of Greater East-Asian Ministry under Tojo.

- Masayuki Tani: Ambassador to Manchukuo, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Concurrently Director of Intelligence Bureau; Ambassador to the Nanking puppet government; and after the war Ambassador to the United States.

- Eiji Amo: Served as Chief of Intelligence Section of Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs; and Director of Intelligence Bureau in Tojo's cabinet.

- Yakijiro Suma: Served as Consul General at Nanking; in 1938, he served as counselor at the Japanese Embassy at Washington; and after 1941, Minister Plenipotentiary to Spain.

- Ryoichi Sasakawa:

All of the uncondemned Class A war criminals were set free by Gen. MacArthur in 1947 and 1948.

San Francisco Peace Treaty

Under Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty signed on Sept. 8, 1951, Japan accepted the jurisdiction of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Article 11 of the treaty reads as follows:

"Japan accepts the judgments of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and of other Allied War Crimes Courts both within and outside Japan, and will carry out the sentences imposed thereby upon Japanese nationals imprisoned in Japan. The power to grant clemency, reduce sentences and parole with respect to such prisoners may not be exercised except on the decision of the government or governments which imposed the sentence in each instance, and on the recommendation of Japan. In the case of persons sentenced by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, such power may not be exercised except on the decision of a majority of the governments represented on the Tribunal, and on the recommendation of Japan."[27]

The parole-for-war-criminals movement

In 1950, after most Allied war crimes trials had ended, thousands of convicted war criminals sat in prisons across Asia and across Europe, detained in the countries where they were convicted. Some executions were still outstanding as many Allied courts agreed to reexamine their verdicts, reducing sentences in some cases and instituting a system of parole, but without relinquishing control over the fate of the imprisoned (even after Japan and Germany had regained their status as sovereign countries).

An intense and broadly supported campaign for amnesty for all imprisoned war criminals ensued (more aggressively in Germany than in Japan at first), as attention turned away from the top wartime leaders and towards the majority of “ordinary” war criminals (Class B/C in Japan), and the issue of criminal responsibility was reframed as a humanitarian problem.

On March 7, 1950, MacArthur issued a directive that reduced the sentences by one-third for good behavior and authorized the parole of those who had received life sentences after fifteen years. Several of those who were imprisoned were released earlier on parole due to ill-health.

The Japanese popular reaction to the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal found expression in demands for the mitigation of the sentences of war criminals and agitation for parole. Shortly after the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in April 1952, a movement demanding the release of B- and C-class war criminals began, emphasizing the "unfairness of the war crimes tribunals" and the "misery and hardship of the families of war criminals." The movement quickly garnered the support of more than ten million Japanese. In the face of this surge of public opinion, the government commented that “public sentiment in our country is that the war criminals are not criminals. Rather, they gather great sympathy as victims of the war, and the number of people concerned about the war crimes tribunal system itself is steadily increasing.”

The parole-for-war-criminals movement was driven by two groups: those from outside who had ‘a sense of pity’ for the prisoners; and the war criminals themselves who called for their own release as part of an anti-war peace movement. The movement that arose out of ‘a sense of pity’ demanded ‘just set them free (tonikaku shakuho o) regardless of how it is done’.

On September 4, 1952, President Truman issued Executive Order 10393,establishing a Clemency and Parole Board for War Criminals to advise the President with respect to recommendations by the Government of Japan for clemency, reduction of sentence, or parole, with respect to sentences imposed on Japanese war criminals by military tribunals.[28]

On May 26, 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles rejected a proposed amnesty for the imprisoned war criminals but instead agreed to "change the ground rules" by reducing the period required for eligibility for parole from 15 years to 10.[29]

By the end of 1958, all Japanese war criminals, including A-, B- and C-class were released from prison and politically rehabilitated. Hashimoto Kingorô, Hata Shunroku, Minami Jirô, and Oka Takazumi were all released on parole in 1954. Araki Sadao, Hiranuma Kiichirô, Hoshino Naoki, Kaya Okinori, Kido Kôichi, Ôshima Hiroshi, Shimada Shigetarô, and Suzuki Teiichi were released on parole in 1955. Satô Kenryô, whom many, including Judge B. V. A. Röling regarded as one of the convicted war criminals least deserving of imprisonment, was not granted parole until March 1956, the last of the Class A Japanese war criminals to be released. On April 7, 1957, the Japanese government announced that, with the concurrence of a majority of the powers represented on the tribunal, the last ten major Japanese war criminals who had previously been paroled were granted clemency and were to be regarded henceforth as unconditionally free from the terms of their parole.

Legacy

In 1978, the kami of 1,068 convicted war criminals, including 14 convicted Class-A war criminals ("crimes against peace") were secretly enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine.[30] The fourteen Class-A war criminals enshrined at Yasukuni include former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, Kenji Doihara, Iwane Matsui, Heitaro Kimura, Koki Hirota, Seishiro Itagaki, Akira Muto, Yosuke Matsuoka, Osami Nagano, Toshio Shiratori, Kiichiro Hiranuma, Kuniaki Koiso and Yoshijiro Umezu.[31]

Since 1978, visits made by Japanese government officials to the Shrine have aroused protests in China and other Asian countries.

In a survey of 3,000 Japanese conducted in 2006 by Asahi News as the 60th anniversary approached, 70% of those questioned were unaware of the details of the trials, a figure that rose to 90% for those in the 20-29 age group. Some 76% of the people polled, however, recognized a certain degree of aggression on Japan's part during the war, while only 7% believed it was a war strictly for self-defense.[32]

See also

- Tokyo Trial (film)

- Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal

- Nanking Massacre

- Nanking (film)

- Command responsibility

- Japanese war crimes

- Nuremberg Trials

- War crime

- INA trials

- Justice Erima Harvey Northcroft Tokyo War Crimes Trial Collection

References

- Adapted by Ming-Hui Yao Basic Facts on the Nanjing Massacre and the Tokyo War Crimes Trial (mirror site). This web article is based on the pamphlet by New Jersey Hong Kong Network, published in September 1993. Both sites are web servers in the domain of China News Digest International, Inc

Movies

- Tokyo Trial (film) released in 2006, directed by Gao Qunshu.[33][34]

Books

- Bass, Gary Jonathan. Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Trials. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Bix, Herbert. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: HarperCollins, 2000.

- Brackman, Arnold C. The Other Nuremberg: the Untold Story of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1987.

- Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: New Press, 1999.

- Frank, Richard B. (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Penguin Books.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Holmes, Linda Goetz (2001). Unjust Enrichment: How Japan's Companies Built Postwar Fortunes Using American POWs. Mechanicsburg, PA, USA: Stackpole Books.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Horowitz, Solis. "The Tokyo Trial" International Conciliation 465 (Nov 1950), 473-584.

- Lael, Richard L. (1982). The Yamashita Precedent: War Crimes and Command Responsibility. Wilmington, Del, USA: Scholarly Resources.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Maga, Timothy P. (2001). Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2177-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Minear, Richard H. (1971). Victor's Justice: The Tokyo War Crimes Trial. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Piccigallo, Philip R. (1979). The Japanese on Trial: Allied War Crimes Operations in the East, 1945-1951. Austin, Texas, USA: University of Texas Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Rees, Laurence (2001). Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II. Boston: Da Capo Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sherman, Christine (2001). War Crimes: International Military Tribunal. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 1563117282.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Totani, Yuma (2009). The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War II. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0674033399.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Web

- International Military Tribunal for the Far East. "Judgment: International Military Tribunal for the Far East". Retrieved 2006-03-29.

- Wu Tianwei The Failure of the Tokyo Trial

- The Postwar Judgement: I. International Military Tribunal for the Far East - Summary and some pictures from the United States National Archives

- Stephen Stratford. Stephen's Study Room: British Military & Criminal History in the period 1900 to 1999: IMTFE

Notes

- ^ "Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East".

- ^ Within documents relating to the IMTFE it is also referred to as the Charter

- ^ Rules of Procedure of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East 25 April 1946

- ^ Brackman, 60

- ^ Minear, 118

- ^ Minear, 120

- ^ a b Minear, pp.122-123

- ^ George Furness, a Defense Counsel stated, "[w]e say that regardless of the known integrity of the individual members of this tribunal they cannot, under the circumstances of their appointment, be impartial; that under the circumstances this trial, both in the present day and in history, will never be free from substantial doubt as to its legality, fairness and impartiality".

- ^ a b Röling and Ruter, The Tokyo judgement : The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, 29 April 1946-12 November 1948, volume 1, p.478

- ^ Röling and Ruter, The Tokyo judgement : The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, 29 April 1946-12 November 1948, volume 1, p.496

- ^ Dower, John (1999). Embracing defeat. p. 447.

- ^ a b Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony, 2003, p. 109

- ^ a b "http://www.commondreams.org/views05/0510-24.htm An Ethical Blank Cheque: British and US mythology about the second world war ignores our own crimes and legitimises Anglo-American war making- the Guardian, May 10, 2005, by Richard Drayton

- ^ http://www.sankei.co.jp/seiron/koukoku/2004/maca/01/MacArthur57.html

- ^ Horowitz, Solis. (1950). "The Tokio Trial". International Conciliation. 465 (Nov): 473–584.

- ^ a b c "The Tokyo Judgment and the Rape of Nanking", by Timothy Brook, The Journal of Asian Studies, August 2001.

- ^ Dower, John (1999). Embracing defeat. W.W. Norton.

- ^ Bix, Herbert (2001). Hirohito and the making of modern Japan. Perennial.

- ^ a b c Dower, John (1999). Embracing defeat. W.W. Norton. pp. 323–325.

- ^ Bix, Herbert (2001). Hirohito and the making of modern Japan. Perennial. p. 583.

- ^ Bix, ibid. p585

- ^ Kumao Toyoda, Sensô saiban yoroku, Taiseisha Kabushiki Kaisha, 1986, p.170-172

- ^ Bix, Herbert (2001). Hirohito and the making of modern Japan. Perennial. p. 584.

- ^ Dower, John (1999). Embracing defeat. W.W. Norton. p. 562.

- ^ ibid. p.496

- ^ Daniel Barenblatt, A plague upon humanity, Harper Collins, 2004, p.222.

- ^ "Taiwan Documents Project - Treaty of Peace with Japan". Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ "Harry S. Truman - Executive Order 10393 - Establishment of the Clemency and Parole Board for War Criminals". Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ Maguire, Peter H. Law and War. p. 255.

- ^ "Where war criminals are venerated". CNN.com. 2003-01-04. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ^ http://japanfocus.org/products/topdf/2443

- ^ http://www.mansfieldfdn.org/polls/poll-06-3.htm

- ^ http://english.cri.cn/3166/2006/09/11/44@137581.htm

- ^ http://english.people.com.cn/200609/19/eng20060919_304080.html