Tobacco

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as an organic pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, it is used in some medicines.[1] In consumption it most commonly appears in the forms of smoking, chewing, snuffing, or dipping tobacco, or snus. Tobacco has long been in use as an entheogen in the Americas. However, upon the arrival of Europeans in North America, it quickly became popularized as a trade item and as a recreational drug. This popularization led to the development of the southern economy of the United States until it gave way to cotton. Following the American Civil War, a change in demand and a change in labor force allowed for the development of the cigarette. This new product quickly led to the growth of tobacco companies, until the scientific controversy of the mid-1900s.

There are many species of tobacco in the plant genus Nicotiana. The word nicotiana (as well as nicotine) is in honor of Jean Nicot, French ambassador to Portugal, who in 1559 sent it as a medicine to the court of Catherine de Medici.[2]

Because of the addictive properties of nicotine, tolerance and dependence develop. Absorption quantity, frequency, and speed of tobacco consumption are believed to be directly related to biological strength of nicotine dependence, addiction, and tolerance.[3][4] The usage of tobacco is an activity that is practiced by some 1.1 billion people, and up to 1/3 of the adult population.[5] The World Health Organization reports it to be the leading preventable cause of death worldwide and estimates that it currently causes 5.4 million deaths per year.[6] Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in developed countries, however they continue to rise in developing countries.

Tobacco is cultivated similarly to other agricultural products. Seeds are sown in cold frames or hotbeds to prevent attacks from insects, and then transplanted into the fields. Tobacco is an annual crop, which is usually harvested mechanically or by hand. After harvest, tobacco is stored for curing, which allows for the slow oxidation and degradation of carotenoids. This allows for the agricultural product to take on properties that are usually attributed to the "smoothness" of the smoke. Following this, tobacco is packed into its various forms of consumption, which include smoking, chewing, sniffing, and so on.

Etymology

The Spanish word "tabaco" is thought to have its origin in Arawakan language, particularly, in the Taino language of the Caribbean. In Taino, it was said to refer either to a roll of tobacco leaves (according to Bartolome de Las Casas, 1552), or to the tabago, a kind of Y-shaped pipe for sniffing tobacco smoke (according to Oviedo; with the leaves themselves being referred to as cohiba).[7]

However, similar words in Spanish and Italian were commonly used from 1410 to define medicinal herbs, originating from the Arabic طبق tabbaq, a word reportedly dating to the 9th century, as the name of various herbs.[8]

History

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

Early developments

Tobacco had already long been used in the Americas when European settlers arrived and introduced the practice to Europe, where it became popular. At high doses, tobacco can become hallucinogenic;[citation needed] accordingly, Native Americans never used the drug recreationally. Instead, it was often consumed as an entheogen; among some tribes, this was done only by experienced shamans or medicine men. [citation needed] Eastern North American tribes carried large amounts of tobacco in pouches as a readily accepted trade item, and often smoked it in pipes, either in defined sacred ceremonies, or to seal a bargain,[9] and they smoked it at such occasions in all stages of life, even in childhood.[10] It is believed that tobacco is a gift from the Creator and that the exhaled tobacco smoke carries one's thoughts and prayers to heaven.[11]

Popularization

Following the arrival of the Europeans, tobacco became increasingly popular as a trade item. It fostered the economy for the southern United States until it was replaced by cotton. Following the American civil war, a change in demand and a change in labor force allowed inventor James Bonsack to create a machine that automated cigarette production.

This increase in production allowed tremendous growth in the tobacco industry until the scientific revelations of the mid-1900s.

Contemporary

Following the scientific revelations of the mid-1900s, tobacco became condemned as a health hazard, and eventually became encompassed as a cause for cancer, as well as other respiratory and circulatory diseases. This led to the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), which settled the lawsuit in exchange for a combination of yearly payments to the states and voluntary restrictions on advertising and marketing of tobacco products.

In the 1970s, Brown & Williamson cross-bred a strain of tobacco to produce Y1. This strain of tobacco contained an unusually high amount of nicotine, nearly doubling its content from 3.2-3.5% to 6.5%. In the 1990s, this prompted the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to use this strain as evidence that tobacco companies were intentionally manipulating the nicotine content of cigarettes.

In 2003, in response to growth of tobacco use in developing countries, the World Health Organization (WHO)[12] successfully rallied 168 countries to sign the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. The Convention is designed to push for effective legislation and its enforcement in all countries to reduce the harmful effects of tobacco. This led to the development of tobacco cessation products.

Biology

Nicotiana

There are many species of tobacco in the genus of herbs Nicotiana. It is part of the nightshade family (Solanaceae) indigenous to North and South America, Australia, south west Africa and the South Pacific.

Many plants contain nicotine, a powerful neurotoxin, that is particularly harmful to insects. However, tobaccos contain a higher concentration of nicotine than most other plants. Unlike many other Solanaceae, they do not contain tropane alkaloids, which are often poisonous to humans and other animals.

Despite containing enough nicotine and other compounds such as germacrene and anabasine and other piperidine alkaloids (varying between species) to deter most herbivores,[13] a number of such animals have evolved the ability to feed on Nicotiana species without being harmed. Nonetheless, tobacco is unpalatable to many species, and therefore some tobacco plants (chiefly tree tobacco, N. glauca) have become established as invasive weeds in some places.

Types

There are a number of types of tobacco including, but are not limited to:

- Aromatic fire-cured, it is cured by smoke from open fires. In the United States, it is grown in northern middle Tennessee, central Kentucky and in Virginia. Fire-cured tobacco grown in Kentucky and Tennessee are used in some chewing tobaccos, moist snuff, some cigarettes, and as a condiment in pipe tobacco blends. Another fire-cured tobacco is Latakia, which is produced from oriental varieties of N. tabacum. The leaves are cured and smoked over smoldering fires of local hardwoods and aromatic shrubs in Cyprus and Syria.

- Brightleaf tobacco, Brightleaf is commonly known as "Virginia tobacco", often regardless of the state where they are planted. Prior to the American Civil War, most tobacco grown in the US was fire-cured dark-leaf. This type of tobacco was planted in fertile lowlands, used a robust variety of leaf, and was either fire cured or air cured. Most Canadian cigarettes are made from 100% pure Virginia tobacco.[14]

- Burley tobacco, is an air-cured tobacco used primarily for cigarette production. In the U.S., burley tobacco plants are started from palletized seeds placed in polystyrene trays floated on a bed of fertilized water in March or April.

- Cavendish is more a process of curing and a method of cutting tobacco than a type. The processing and the cut are used to bring out the natural sweet taste in the tobacco. Cavendish can be produced from any tobacco type, but is usually one of, or a blend of Kentucky, Virginia, and burley, and is most commonly used for pipe tobacco and cigars.

- Criollo tobacco is a type of tobacco, primarily used in the making of cigars. It was, by most accounts, one of the original Cuban tobaccos that emerged around the time of Columbus.

- Dokham, is a tobacco originally grown in Iran, mixed with leaves, bark, and herbs for smoking in a midwakh.

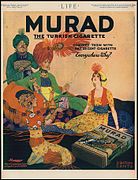

- Turkish tobacco, is a sun-cured, highly aromatic, small-leafed variety (Nicotiana tabacum) that is grown in Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, and Macedonia. Originally grown in regions historically part of the Ottoman Empire, it is also known as "oriental". Many of the early brands of cigarettes were made mostly or entirely of Turkish tobacco; today, its main use is in blends of pipe and especially cigarette tobacco (a typical American cigarette is a blend of bright Virginia, burley and Turkish).

- Perique, a farmer called Pierre Chenet is credited with first turning this local tobacco into the Perique in 1824 through the technique of pressure-fermentation. Considered the truffle of pipe tobaccos, it is used as a component in many blended pipe tobaccos, but is too strong to be smoked pure. At one time, the freshly moist Perique was also chewed, but none is now sold for this purpose. It is typically blended with pure Virginia to lend spice, strength, and coolness to the blend.

- Shade tobacco, is cultivated in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Early Connecticut colonists acquired from the Native Americans the habit of smoking tobacco in pipes, and began cultivating the plant commercially, even though the Puritans referred to it as the "evil weed". The industry has weathered some major catastrophes, including a devastating hailstorm in 1929, and an epidemic of brown spot fungus in 2000, but is now in danger of disappearing altogether, given the value of the land to real estate speculators.

- White burley, in 1865, George Webb of Brown County, Ohio planted red burley seeds he had purchased, and found that a few of the seedlings had a whitish, sickly look. The air-cured leaf was found to be more mild than other types of tobacco.

- Wild tobacco, is native to the southwestern United States, Mexico, and parts of South America. Its botanical name is Nicotiana rustica.

- Y1 is a strain of tobacco cross-bred by Brown & Williamson in the 1970s to obtain an unusually high nicotine content. In the 1990s, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used it as evidence that tobacco companies were intentionally manipulating the nicotine content of cigarettes.[15]

Impact

Social

This section needs expansion with: information expanding the effects of tobacco on cultural practices. You can help by adding to it. (January 2009) |

Smoking in public was for a long time something reserved for men, and when done by women was sometimes associated with promiscuity.[citation needed] In Japan, during the Edo period, prostitutes and their clients often approached one another under the guise of offering a smoke. The same was true in 19th century Europe.[16]

Following the American Civil War the usage of tobacco, primarily in cigarettes, became associated with masculinity and power, and is an iconic image associated with the stereotypical capitalist. Today, tobacco is often rejected; this has spawned quitting associations and anti-smoking campaigns. Bhutan is the only country in the world where tobacco sales are illegal.[17]

Demographic

Research is limited mainly to tobacco smoking, which has been studied more extensively than any other form of consumption. As of 2000, smoking is practiced by some 1.22 billion people, of which men are more likely to smoke than women[18] (however the gender gap declines with age),[19][20] poor more likely than rich, and people in developing countries or transitional economies are more likely than people in developed countries.[21] As of 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that of the 58.8 million deaths to occur globally,[22] 5.4 million are tobacco-attributed.[23]

Health

The risks associated with tobacco use include diseases affecting the heart and lungs, with smoking being a major risk factor for heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and cancer (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, and pancreatic cancer).

The World Health Organization estimates that tobacco caused 5.4 million deaths in 2004[24] and 100 million deaths over the course of the 20th century.[25] Similarly, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes tobacco use as "the single most important preventable risk to human health in developed countries and an important cause of premature death worldwide."[26]

Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world. Smoking rates in the United States have dropped by half from 1965 to 2006, falling from 42% to 20.8% in adults.[27] In the developing world, tobacco consumption is rising by 3.4% per year.[28]

When the market for tobacco reduced in the West, the industry looked to India and China for 'emerging markets'. Dr. Sharad Vaidya, a cancer surgeon worked tirelessly to fight this, through research, advocacy and passion. He successfully raised awareness, introduced it in the curriculum of children and managed to establish legislation banning public smoking, stopping sports sponsorship, sale to those under 21 years of age.

China is the world's largest tobacco market. Considerable progress has been made in eliminating advertising, posting health warnings, and banning smoking from public buildings. Many doctors, however, smoke and neglect to warn their patients that smoking increases their risk for disease. Judith Mackay, a Hong Kong-based physician, has been a relentless and effective campaigner, assisting Chinese health officials in the effort to reduce smoking and its immense health, social, and economic costs. Among her projects is the Tobacco Atlas. Her work caused Time Magazine to name her to its 2007 list of the most influential figures across the globe. In a 2010 talk at the USC U.S.-China Institute, Mackay summarized the progress that's been made in China and the challenges that remain.[29]

Economic

This section needs expansion with: discussion of the impact on the poor, taxation, and so forth. You can help by adding to it. (January 2009) |

"Much of the disease burden and premature mortality attributable to tobacco use disproportionately affect the poor", and of the 1.22 billion smokers, 1 billion of them live in developing or transitional economies.[21]

In Indonesia, the lowest income group spends 15% of its total expenditures on tobacco. In Egypt, more than 10% of households expediture in low-income homes is on tobacco. The poorest 20% of households in Mexico spend 11% of their income on tobacco.[30]

Production

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

Cultivation

Tobacco is cultivated similar to other agricultural products. Seeds were at first quickly scattered onto the soil. However, young plants came under increasing attack from flea beetles (Epitrix cucumeris or Epitrix pubescens), which caused destruction of half the tobacco crops in United States in 1876. By 1890 successful experiments were conducted that placed the plant in a frame covered by thin fabric. Today, tobacco is sown in cold frames or hotbeds, as their germination is activated by light.

In the United States, tobacco is often fertilized with the mineral apatite, which partially starves the plant of nitrogen, to produce a more desired flavor. Apatite, however, contains radium, lead 210, and polonium 210—which are known radioactive carcinogens.

After the plants have reached relative maturity, they are transplanted into the fields, in which a relatively large hole is created in the tilled earth with a tobacco peg. Various mechanical tobacco planters were invented in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to automate the process: making the hole, fertilizing it, guiding the plant in — all in one motion.

Tobacco is cultivated annually, and can be harvested in several ways. In the oldest method, the entire plant is harvested at once by cutting off the stalk at the ground with a sickle. In the nineteenth century, bright tobacco began to be harvested by pulling individual leaves off the stalk as they ripened. The leaves ripen from the ground upwards, so a field of tobacco may go through several so-called "pullings," more commonly known as topping (topping always refers to the removal of the tobacco flower before the leaves are systematically removed and, eventually, entirely harvested. As the industrial revolution took hold, harvesting wagons used to transport leaves were equipped with man-powered stringers, an apparatus that used twine to attach leaves to a pole. In modern times, large fields are harvested mechanically or by hand, although topping the flower and in some cases the plucking of immature leaves is still done by hand.

Curing

Curing and subsequent aging allow for the slow oxidation and degradation of carotenoids in tobacco leaf. This produces certain compounds in the tobacco leaves, and gives a sweet hay, tea, rose oil, or fruity aromatic flavor that contributes to the "smoothness" of the smoke. Starch is converted to sugar, which glycates protein, and is oxidized into advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), a caramelization process that also adds flavor. Inhalation of these AGEs in tobacco smoke contributes to atherosclerosis and cancer.[31] Levels of AGE's is dependent on the curing method used.

Tobacco can be cured through several methods, including:

- Air cured tobacco is hung in well-ventilated barns and allowed to dry over a period of four to eight weeks. Air-cured tobacco is low in sugar, which gives the tobacco smoke a light, sweet flavor, and high in nicotine. Cigar and burley tobaccos are air cured.

- Fire cured tobacco is hung in large barns where fires of hardwoods are kept on continuous or intermittent low smoulder and takes between three days and ten weeks, depending on the process and the tobacco. . Fire curing produces a tobacco low in sugar and high in nicotine. Pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and snuff are fire cured.

- Flue cured tobacco was originally strung onto tobacco sticks, which were hung from tier-poles in curing barns (Aus: kilns, also traditionally called Oasts). These barns have flues run from externally-fed fire boxes, heat-curing the tobacco without exposing it to smoke, slowly raising the temperature over the course of the curing. The process generally takes about a week. This method produces cigarette tobacco that is high in sugar and has medium to high levels of nicotine.

- Sun-cured tobacco dries uncovered in the sun. This method is used in Turkey, Greece and other Mediterranean countries to produce oriental tobacco. Sun-cured tobacco is low in sugar and nicotine and is used in cigarettes.

Consumption

Tobacco is consumed in many forms and through a number of different methods. Below are examples including, but not limited to, such forms and usage.

- Beedi are thin, often flavored, south Asian cigarettes made of tobacco wrapped in a tendu leaf, and secured with colored thread at one end.

- Chewing tobacco is one of the oldest ways of consuming tobacco leaves. It is consumed orally, in two forms: through sweetened strands, or in a shredded form. When consuming the long sweetened strands, the tobacco is lightly chewed and compacted into a ball. When consuming the shredded tobacco, small amounts are placed at the bottom lip, between the gum and the teeth, where it is gently compacted, thus it can often be called dipping tobacco. Both methods stimulate the saliva glands, which led to the development of the spittoon.

- Cigars are tightly rolled bundles of dried and fermented tobacco, which is ignited so its smoke may be drawn into the smoker's mouth.

- Cigarettes are a product consumed through inhalation of smoke and manufactured from cured and finely cut tobacco leaves and reconstituted tobacco, often combined with other additives, then rolled or stuffed into a paper cylinder.

- Creamy snuffs are tobacco paste, consisting of tobacco, clove oil, glycerin, spearmint, menthol, and camphor, and sold in a toothpaste tube. It is marketed mainly to women in India, and is known by the brand names Ipco (made by Asha Industries), Denobac, Tona, Ganesh. It is locally known as "mishri" in some parts of Maharashtra.

- Dipping tobaccos are a form of smokeless tobacco. Dip is occasionally referred to as "chew", and because of this, it is commonly confused with chewing tobacco, which encompasses a wider range of products. A small clump of dip is 'pinched' out of the tin and placed between the lower or upper lip and gums.

- Gutka is a preparation of crushed betel nut, tobacco, and sweet or savory flavorings. It is manufactured in India and exported to a few other countries. A mild stimulant, it is sold across India in small, individual-size packets.

- Hookah is a single or multi-stemmed (often glass-based) water pipe for smoking. Originally from India, the hookah has gained immense popularity, especially in the Middle East. A hookah operates by water filtration and indirect heat. It can be used for smoking herbal fruits or cannabis.

- Kreteks are cigarettes made with a complex blend of tobacco, cloves and a flavoring "sauce". It was first introduced in the 1880s in Kudus, Java, to deliver the medicinal eugenol of cloves to the lungs.

- Roll-Your-Own, often called rollies or roll ups, are very popular, particularly in European countries. These are prepared from loose tobacco, cigarette papers and filters all bought separately. They are usually much cheaper to make.

- Pipe smoking typically consists of a small chamber (the bowl) for the combustion of the tobacco to be smoked and a thin stem (shank) that ends in a mouthpiece (the bit). Shredded pieces of tobacco are placed into the chamber and ignited.

- Snuff is a generic term for fine-ground smokeless tobacco products. Originally the term referred only to dry snuff, a fine tan dust popular mainly in the eighteenth century. Snuff powder originated in the UK town of Great Harwood, and was famously ground in the town's monument prior to local distribution and transport further up north to Scotland. There are two major varieties: European (dry) and American (moist)—though American snuff is often called dipping tobacco.

- Snus is a steam-cured moist powder tobacco product that is not fermented, and does not induce salivation. It is consumed by placing it in the mouth against the gums for an extended period of time. It is a form of snuff used in a manner similar to American dipping tobacco, but does not require regular spitting.

- Topical tobacco paste is sometimes recommended as a treatment for wasp, hornet, fire ant, scorpion, and bee stings.[32] An amount equivalent to the contents of a cigarette is mashed in a cup with about a 0.5 to 1 teaspoon of water to make a paste that is then applied to the affected area.

- Tobacco water is a traditional organic insecticide used in domestic gardening. Tobacco dust can be used similarly. It is produced by boiling strong tobacco in water, or by steeping the tobacco in water for a longer period. When cooled, the mixture can be applied as a spray, or 'painted' on to the leaves of garden plants, where it kills insects.

Global Production

Trends

Production of tobacco leaf increased by 40% between 1971, during which 4.2 million tons of leaf were produced, and 1997, during which 5.9 million tons of leaf were produced.[33] According to the Food and Agriculture organization of the UN, tobacco leaf production is expected to hit 7.1 million tons by 2010. This number is a bit lower than the record high production of 1992, during which 7.5 million tons of leaf were produced.[34] The production growth was almost entirely due to increased productivity by developing nations, where production increased by 128%.[35] During that same time period, production in developing countries actually decreased.[34] China’s increase in tobacco production was the single biggest factor in the increase in world production. China’s share of the world market increased from 17% in 1971 to 47% in 1997.[33] This growth can be partially explained by the existence of a high import tariff on foreign tobacco entering China. While this tariff has been reduced from 64% in 1999 to 10% in 2004,[36] it still has led to local, Chinese cigarettes being preferred over foreign cigarettes because of their lower cost.

Every year 6.7 million tons of tobacco are produced throughout the world. The top producers of tobacco are China (39.6%), India (8.3%), Brazil (7.0%) and the United States (4.6%).[37]

Major Producers

China

Around the peak of global tobacco production there were 20 million rural Chinese households producing tobacco on 2.1 million hectares of land [38]. While it is the major crop for millions of Chinese farmers, growing tobacco, is not as profitable as cotton or sugar cane. This is because the Chinese government sets the market price. While this price is guaranteed, it is lower than the natural market price, because of the lack of market risk. To further control tobacco in their borders, China founded a State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (STMA) in 1982. STMA control tobacco production, marketing, imports and exports and contributes 12% to the nation's national income [39]. As noted above, despite the income generated for the state by profits from state-owned tobacco companies and the taxes paid by companies and retailers, China's government has acted to reduce tobacco use. At the same time, increasing incomes has enabled more people in China to smoke and to consume more cigarettes.[40]

Brazil

In Brazil around 135,000 family farmers cite tobacco production as their main economic activity.[38] Tobacco has never exceeded 0.7% of the country’s total cultivated area.[41] In the southern regions of Brazil, Virginia and Amarelinho flue-cured tobacco as well as Burley and Galpao Comun air-cured tobacco are produced. These types of tobacco are used for cigarettes. In the northeast, darker, air- and sun-cured tobacco is grown. These types of tobacco are used for cigars, twists and dark-cigarettes.[41] Brazil’s government has made attempts to reduce the production of tobacco, but has not had a successful systematic anti-tobacco farming initiative. Brazil’s government, however, provides small loans for family farms, including those that grow tobacco, through the Programa Nacional de Fortalecimiento da Agricultura Familiar (PRONAF).[42]

India

India's Tobacco Board is headquartered in Guntur in the state of Andhra Pradesh.[43] India has 96,865 registered tobacco farmers[44] and many more who are not registered. Around 0.25% of India’s cultivated land is used for tobacco production [45]. Since 1947, the Indian government has supported growth in the tobacco industry. India has seven tobacco research centers that are located in Madras, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, Bihar, Mysore, West Bengal, and Rajamundry [44]. Rajahmundry houses the core research institute. The government has set up a Central Tobacco Promotion Council, which works to increase exports of Indian tobacco.

Problems in Tobacco Production

Child Labor

The International Labour Office reported that the most child-laborers work in agriculture, which is one of the most hazardous types of work.[46] The tobacco industry houses some of these working children. There is widespread use of children on farms in Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Malawi, the United States and Zimbabwe.[47] While some of these children work with their families on small family-owned farms, others work on large plantations. In late 2009 reports were released by the London-based human-rights group Plan International, claiming that child labor was common on Malawi (producer of 1.8% of the world’s tobacco[33]) tobacco farms. The organization interviewed 44 teens, who worked full-time on farms during the 2007-2008 growing season. The child-laborers complained of low pay, long hours as well as physical and sexual abuse by their supervisors.[48] They also reported suffering from “green tobacco sickness,” a form of nicotine poisoning. When wet leaves are handled, nicotine from the leaves gets absorbed in the skin and causes nausea, vomiting and dizziness. Children were exposed to 50-cigarettes worth of nicotine through direct contact with tobacco leaves. This level of nicotine in children can permanently alter brain structure and function.[46]

Families that farm tobacco often have to make the difficult decision between having their children work or go to school. Unfortunately working often beats education because tobacco farmers, especially in the developing world, cannot make enough money from their crop to survive without the cheap labor that children provide.

Economy

The cultivation of tobacco is economically detrimental to the countries that produce it, especially those that are still developing. When resources are put into tobacco production, they are taken away from food production. Large amount of firewood, that could be used domestically for fuel and heating, are instead used for the curing of tobacco.

A large percent of the profits from tobacco production go to large tobacco companies rather than local tobacco farmers. Also many countries have government subsides for tobacco farming, which do not make economic sense.[49] Major tobacco companies have encouraged global tobacco production. Philip Morris, British American Tobacco and Japan Tobacco each own or lease tobacco manufacturing facilities in at least 50 countries and buy crude tobacco leaf from at least 12 more countries.[50] This encouragement, along with government subsidies has led to a glut in the tobacco market. This surplus has resulted in lower prices, which are devastating to small-scale tobacco farmers. According to the World Bank, between 1985 and 2000 the inflation-adjusted price of tobacco dropped 37%.[51]

Environment

Tobacco production requires the use of a large amount of pesticides. Tobacco companies recommend up to 16 separate applications of pesticides just in the period between planting the seeds in greenhouses and transplanting the young plans to the field.[52] Pesticide use has been worsened by the desire to produce bigger crops in less time because of the decreasing market value of tobacco. Pesticides often harm tobacco farmers because they are unaware of the health affects and the proper safety protocol for working with pesticides. These pesticides as well as fertilizers, end of in the soil, the waterway and the food chain.[53] Coupled with child labor, pesticides pose an even greater threat. Early exposure to pesticides may increase a child's life long cancer risk as well as harm his or her nervous and immune systems.[54]

Tobacco is a crop that leeches nutrients, such as phosphorus, nitrogen and potassium, from the soil at a rate higher than any other major crop.[55] This leads to dependence on fertilizers.

Furthermore, the wood for the curing of tobacco, leads to deforestation. While some big tobacco producers such as China and the United States have access to petroleum, coal and natural gas, which can be used as alternatives to wood, most developing countries still rely on wood in the curing process.[56] Brazil alone uses the wood of 60 million trees per year for curing, packaging and rolling cigarettes.[52] Deforestation is a factor in flooding, decreased soil productivity and general climate change.

Art

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Advertising

Tobacco advertising is the advertising of tobacco products or use (typically cigarette smoking) by the tobacco industry through a variety of media including sponsorship, particularly of sporting events. It is now one of the most highly regulated forms of marketing. Some or all forms of tobacco advertising are banned in many countries.

-

Belomorkanal - Russian cigarettes

-

Hans Rudi Erdt: Problem Cigarettes, 1912

-

French Painted Mural Advertisement

-

Tobacco display in Munich

-

Advertisement for "Murad" Turkish cigarettes 1918

-

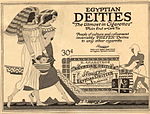

Advertisement for "Egyptian Deities" cigarettes 1919

Cinema

Gallery

-

Tobacco can also be pressed into plugs and sliced into flakes.

-

A historic kiln in Myrtleford, Victoria, Australia.

-

Broadleaf tobacco inspected in Chatham, Virginia, United States.

-

Tobacco field in northern Poland

-

Flowers of tobacco plant in northern Poland in September

See also

References

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ colonia 13 509 Heading: 1550–1575 Tobacco, Europe.

- ^ "Tobacco Facts - Why is Tobacco So Addictive?". Tobaccofacts.org. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ "Philip Morris Information Sheet". Stanford.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Saner L. Gilman and Zhou Xun, "Introduction" in Smoke; p. 26

- ^ "WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008 (foreword and summary)" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008: 8.

Tobacco is the single most preventable cause of death in the world today.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "World Association of International Studies, Stanford University".

- ^ "Online Etymological Dictionary".

- ^ eg. Heckewelder, History, Manners and Customs of the Indian Nations who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania, p. 149 ff.

- ^ "They smoke with excessive eagerness ... men, women, girls and boys, all find their keenest pleasure in this way." - Dièreville describing the Mi'kmaq, c. 1699 in Port Royal.

- ^ Tobacco: A Study of Its Consumption in the United States, Jack Jacob Gottsegen, 1940, p. 107.

- ^ "WHO | WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC)". Who.int. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Panter et al. (1990)

- ^ Imperial Tobacco Canada - Our products

- ^ "Inside the Tobacco Deal - interview with David Kessler". PBS. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ Timon Screech, "Tobacco in Edo Period Japan" in Smoke, pp. 92-99

- ^ The First Nonsmoking Nation, Slate.com

- ^ "Guindon & Boisclair" 2004, pp. 13-16.

- ^ Women and the Tobacco Epidemic: Challenges for the 21st Century 2001, pp.5-6.

- ^ Surgeon General's Report — Women and Smoking 2001, p.47.

- ^ a b "WHO/WPRO-Tobacco". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2005. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update 2008, p.8.

- ^ The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update 2008, p.23.

- ^ WHO global burden of disease report 2008

- ^ WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008

- ^ "Nicotine: A Powerful Addiction." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2006

- ^ WHO/WPRO-Smoking Statistics

- ^ http://china.usc.edu/ShowArticle.aspx?articleID=1991

- ^ MPOWER p. 26

- ^ Cerami C, Founds H, Nicholl I, Mitsuhashi T, Giordano D, Vanpatten S, Lee A, Al-Abed Y, Vlassara H, Bucala R, Cerami A (1997). "Tobacco smoke is a source of toxic reactive glycation products". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (Pnas). 94 (25): 13915–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13915. PMC 28407. PMID 9391127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beverly Sparks, "Stinging and Biting Pests of People" Extension Entomologist of the University of Georgia College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences Cooperative Extension Service.

- ^ a b c Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "Projection of tobacco production, consumption and trade for the year 2010." Rome, 2003.

- ^ a b The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.Higher World Tobacco use expected by 2010-growth rates slowing down." (Rome, 2004).

- ^ Rowena Jacobs, et. al, "The Supply-Side Effects Of Tobacco Control Policies," in Tobacco Control in Developing Countries, Jha and Chaloupka eds., Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ^ Hu T-W, Mao Z, et al. "China at the Crossroads: The Economics of Tobacco and Health". Tobacco Control. 2006;15:i37–i41.

- ^ US Census Bureau-Foreign Trade Statistics, (Washington DC; 2005)

- ^ a b Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Issues in the Global Tobacco Economy.”

- ^ People's Republic of China. "State Tobacco Monopoly Administration <<http://www.gov.cn/english/2005-10/03/content_74295.htm>>.

- ^ USC U.S.-China Institute, "Talking Points, February 3–17, 2010: http://china.usc.edu/ShowArticle.aspx?articleID=1992

- ^ a b International Tobacco Growers’ Association. “Tobacco Farming: Sustainable Alternative.” Volume II East Sussix:

- ^ High Level Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor. “Report from South America.” 2006.

- ^ http://tobaccoboard.com/component/option,com_contact/Itemid,105/lang,english/

- ^ a b Shoba, John and Shailesh Vaite. Tobacco and Poverty: Observations from India and Bangladesh. Canada, 2002.

- ^ 3. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Issues in the Global Tobacco Economy.”

- ^ a b ILO. International Hazard Datasheets on Occupations: Field Crop Worker

- ^ UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 1997 (Oxford, 1997); US Department of Agriculture By the Sweat and Toil of Children Volume II: The Use of Child Labor in US Agricultural Imports & Forced and Bonded Child Labor (Washington, 1995); ILO Bitter Harvest: Child Labour in Agriculture (Geneva, 1997); ILO Child Labour on Commerical Agriculture in Africa (Geneva 1997)

- ^ Plan International. "Malawi Child Tobacco Pickers' '50-a-day habit" http://plan-international.org/about-plan/resources/media-centre/press-releases/malawi-child-tobacco-pickers-50-a-day-habit/?searchterm=tobacco

- ^ World Health Organization. Tobacco Epidemic: Much More than a Health Issue.” Geneva: 1997.

- ^ “International Cigarette Manufacturers,” Tobacco Reporter, March 2001

- ^ 14. Tobacco Free Kids. “Golden Leaf, Barren Harvest: The Costs of Tobacco Farming.”<< http://tobaccofreekids.org/campaign/global/FCTCreport1.pdf>>

- ^ a b Taylor, Peter, "Smoke Ring: The Politics of Tobacco", Panos Briefing Paper, September 1994, London

- ^ FAO Yearbook, Production, Volume 48, 1995

- ^ National Research Council, 1995, Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children, National Academy Press.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund. Agriculture and Environment: Tobacco. <http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/agriculture_impacts/tobacco/environmental_impacts/deforestation/>

- ^ World Wildlife Fund. Agriculture and Environment: Tobacco. <http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/agriculture_impacts/tobacco/environmental_impacts/deforestation/>

Bibliography

- "WHO REPORT on the global TOBACCO epidemic" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - "The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - G. Emmanuel Guindon, David Boisclair (2003). "Past, current and future trends in tobacco use" (PDF). Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - The World Health Organization, and the Institute for Global Tobacco Control, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (2001). "Women and the Tobacco Epidemic: Challenges for the 21st Century" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Surgeon General's Report — Women and Smoking". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Richard Peto, Alan D Lopez, Jillian Boreham, and Michael Thun (2006). "Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries 1950-2000: indirect estimates from national vital statistics" (PDF). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gilman, Sander L.; Zhou, Xun (2004). Smoke: A Global History of Smoking. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861892003. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|coauthors=,|nopp=,|month=,|separator=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help) - "Cancer Facts and Figures 2004: Basic Cancer Facts". American Cancer Society. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Environmental and Heritable Factors in the Causation of Cancer — Analyses of Cohorts of Twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. Vol. 343. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lastauthoramp=,|nopp=,|separator=,|laydate=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Montesano, R., and Hall, J. (2001). "Environmental causes of human cancers". European Journal of Cancer. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Janet E. Ash, Maryadele J. O'Neil, Ann Smith, Joanne F. Kinneary (1997) [1996]. The Merck Index (12 ed.). Merk and Co. ISBN 0412759403.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Breen, T. H. (1985). Tobacco Culture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00596-6. Source on tobacco culture in eighteenth-century Virginia pp. 46–55

- Burns, Eric. The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007.

- W.K. Collins and S.N. Hawks. "Principles of Flue-Cured Tobacco Production" 1st Edition, 1993

- Fuller, R. Reese (Spring 2003). Perique, the Native Crop. Louisiana Life.

- Gately, Iain. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Grove Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8021-3960-4.

- Graves, John. "Tobacco that is not Smoked" in From a Limestone Ledge (the sections on snuff and chewing tobacco) ISBN 0-394-51238-3

- Grehan, James. “Smoking and “Early Modern” Sociability: The Great Tobacco Debate in the Ottoman Middle East (Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries)”. The American Historical Review, Vol. III, Issue 5. 2006. 22 March 2008 http://www.historycooperative.org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/journals/ahr/111.5/grehan.html

- Killebrew, J. B. and Myrick, Herbert (1909). Tobacco Leaf: Its Culture and Cure, Marketing and Manufacture. Orange Judd Company. Source for flea beetle typology (p. 243)

- Murphey, Rhoads. Studies on Ottoman Society and Culture: 16th-18th Centuries. Burlington, VT: Ashgate: Variorum, 2007 ISBN 978-0-7546-5931-0 ISBN 0-7546-5931-3

- Price, Jacob M. “Tobacco Use and Tobacco Taxation: A battle of Interests in Early Modern Europe”. Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology. Jordan Goodman, et al. New York: Routledge, 1995 166-169 ISBN 0-415-09039-3

- Poche, L. Aristee (2002). Perique tobacco: Mystery and history.

- Tilley, Nannie May The Bright Tobacco Industry 1860–1929 ISBN 0-405-04728-2. Source on flea beetle prevention (pp. 39–43), and history of flue-cured tobacco

- Rivenson A., Hoffmann D., Propokczyk B. et al. Induction of lung and pancreas exocrine tumors in F344 rats by tobacco-specific and areca-derived N-nitrosamines. Cancer Res (48) 6912–6917, 1988. (link to abstract; free full text pdf available)

- Schoolcraft, Henry R. Historical and Statistical Information respecting the Indian Tribes of the United States (Philadelphia, 1851–57)

- Shechter, Relli. Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East: The Egyptian Tobacco Market 1850–2000. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2006 ISBN 1-84511-137-0

External links

- Growing Nicotiana species (Plot55.com)

- Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Sheet - Wild tobacco

- Ottoman Back Archives and Research Centre

- Questions on European Union partial ban on some smokeless tobacco products (i.e. snus)

- Scientists Search for Healthy Uses for Tobacco

- Timeline of tobacco history

- The European tobacco growers website

- The Legacy Tobacco Documents Library

- UCSF Tobacco Industry Videos Collection

- CDC - Smoking and Tobacco Use Fact Sheet

- TobReg - WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation