Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Hitchens | |

|---|---|

Hitchens in 2007 | |

| Occupation | Author, journalist, activist, pundit |

| Nationality | British / American |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Genre | Polemicism, journalism, essays, biography, literary criticism |

| Notable works | The Missionary Position god Is Not Great |

| Relatives | Peter Hitchens (brother) |

Christopher Eric Hitchens (born 13 April 1949) is an English-American author and journalist. His books, essays, and journalistic career have spanned more than four decades, making him a public intellectual, and a staple of talk shows and lecture circuits. He has been a columnist and literary critic at The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Slate, World Affairs, The Nation, Free Inquiry, and a variety of other media outlets.

As a political observer, polemicist and self-defined radical, Hitchens rose to prominence as a fixture of the left-wing publications of both his native United Kingdom and United States. Hitchens's departure from the established political left began in 1989 after what he called the "tepid reaction" of the European left following Ayatollah Khomeini's issue of a fatwā calling for the murder of Salman Rushdie. The 11 September 2001 attacks strengthened his embrace of an interventionist foreign policy and his vociferous criticism of what he called "fascism with an Islamic face". Hitchens's support for interventionism, employment of the term "Islamofascist" and his notable support for the Iraq War have caused his critics to label him a "neoconservative". Hitchens, however, refuses to embrace this designation,[2][3] insisting that he is "not any kind of conservative."[4]

Hitchens is an atheist and has been identified as being an exponent of the "new atheism" movement. Hitchens is a secular humanist and anti-theist,[5] and describes himself as a believer in the philosophical values of the Age of Enlightenment. One of his most famous arguments opposing theism is that the concept of God or a supreme being is a totalitarian belief that destroys individual freedom, and that free expression and scientific discovery should replace religion, which inhibits these things, as a means of teaching ethics and defining human civilization. Hitchens wrote at length on atheism and the nature of religion in the 2007 book God Is Not Great.

Hitchens is known for his ardent admiration of George Orwell, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson, and also for his excoriating critiques of Mother Teresa, Bill and Hillary Clinton, and Henry Kissinger, among others. These views, often stylized as contrarian, along with his argumentative and confrontational style of debate and writing, have made him both a lauded and controversial figure.

Retaining his British citizenship, Hitchens became a United States citizen on the steps of the Jefferson Memorial, on his fifty-eighth birthday on 13 April 2007.[6] In September 2008, he was made a media fellow at the Hoover Institution.[7] His latest book, entitled Hitch-22: A Memoir, was published in June 2010.[8] Touring for this book was cut short later the same month in order for Hitchens to begin treatment for newly diagnosed oesophageal cancer.[9] Hitchens currently resides in Washington DC.

Life and career

Early life

In an article in the Guardian Unlimited on 14 April 2002, Hitchens says he could be considered Jewish because Jewish descent is matrilineal. According to Hitchens, when his brother Peter Hitchens took his fiancée to meet their maternal grandmother, Dodo, who was then in her 90s, Dodo said, "She's Jewish, isn't she?" and then announced: "Well, I've got something to tell you. So are you." She said that her real surname was Levin, not Lynn, that her ancestors had the family name Blumenthal, and were from Poland.[10] His brother has researched the family tree and says they are one-thirtysecond Jewish.[10] His mother Yvonne and father Eric met in Scotland while both serving in the Royal Navy during World War II, Yvonne a "Wren," a member of the Women's Royal Naval Service,[11] and Eric, a "purse-lipped and silent" imperialistic Navy Commander whose ship (Hitchens claimed) had sunk Nazi Germany's Scharnhorst in the Battle of North Cape.[1] His father's Naval career required the family to move and reside in bases throughout the United Kingdom and its dependencies, including in Malta, where his brother Peter was born in Sliema in 1951.

Due to Yvonne arguing that "if there is going to be an upper class in this country, then Christopher is going to be in it,"[12] he was educated at the independent Leys School, in Cambridge, and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was tutored by Steven Lukes, and read philosophy, politics, and economics. Hitchens was "bowled over" in his adolescence by Richard Llewellyn's How Green Was My Valley on the plight of Welsh miners, Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon, Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, R. H. Tawney's critique on Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, and the works of George Orwell.[11] In 1968 he took part in the TV quiz show University Challenge.[13] Hitchens has written of his homosexual experiences when in boarding school in his memoir, Hitch-22.[14] These experiences spilled over into his college years when he allegedly had relationships with two men who eventually became a part of Margaret Thatcher's government.[15]

In the 1960s, Hitchens joined the political left, drawn by his anger over the Vietnam war, nuclear weapons, racism, and "oligarchy", including that of "the unaccountable corporation." He would express affinity to the politically charged countercultural and protest movements of the 1960s and 70s. However, he deplored the rife recreational drug use of the time, which he describes as hedonistic.[16]

He joined the Labour Party in 1965, but was expelled in 1967 along with the majority of the Labour students' organization, because of what Hitchens called "Prime Minister Harold Wilson's contemptible support for the war in Vietnam."[17] Under the influence of Peter Sedgwick, translator of Russian revolutionary and Soviet dissident Victor Serge, Hitchens forged an ideological interest in Trotskyist and anti-Stalinist socialism.[11] Shortly thereafter, he joined "a small but growing post-Trotskyite Luxemburgist sect."[18] Throughout his student days, he was on many occasions arrested and assaulted in the various political protests and activities in which he participated.

He then became a correspondent for the magazine International Socialism,[19] which was published by the International Socialists, the forerunners of today's British Socialist Workers Party. This group was broadly Trotskyist, but differed from more orthodox Trotskyist groups in its refusal to defend communist states as "workers' states". This was symbolized in their slogan "Neither Washington nor Moscow but International Socialism."

Fleet Street career (1970–81)

Hitchens left Oxford with a third class degree.[20] His first job was with the London Times Higher Education Supplement, where he served as social science editor. Hitchens admits that he hated the job and was later fired from the position, recalling that "I sometimes think if I'd been any good at that job, I might still be doing it."[citation needed] In the 1970s, he went on to work for the New Statesman, where he became friends with, among others, Martin Amis and Ian McEwan. At the New Statesman, he acquired a reputation as a fierce left-winger, aggressively attacking targets such as Henry Kissinger, the Vietnam War, and the Roman Catholic Church.

In November 1973, Hitchens' mother committed suicide in Athens in a suicide pact with her lover, a former clergyman named Timothy Bryan;[11] in what was initially thought to be a murder scene, after overdosing on sleeping pills in adjoining hotel rooms with Timothy slashing his wrists in the bath to be sure. He flew alone to Athens to recover her remains. While there he reported on the Greek constitutional crisis of the military junta that was happening at the time. It became his first leading article for The New Statesman. Hitchens stated his belief that his mother was pressured into taking her own life under the fear of his father becoming aware of her infidelity, in an already strained and unhappy marriage, and with both her children now independent adults.[21]

American career (1981–present)

After emigrating to the United States in 1981, Hitchens wrote for The Nation. While at The Nation he penned vociferous critiques of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and American foreign policy in South and Central America.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28] He became a Contributing Editor of Vanity Fair in 1992,[29] writing ten columns a year. He left The Nation in 2002, after profoundly disagreeing with other contributors over the Iraq War. There is speculation that Hitchens was the inspiration for Tom Wolfe's character Peter Fallow, in the 1987 novel The Bonfire of the Vanities,[24] but others—including Hitchens—believe it to be Spy Magazine's "Ironman Nightlife Decathlete" Anthony Haden-Guest.[30][31]

Hitchens spent part of his early career in journalism as a foreign correspondent in Cyprus.[32] Through his work there he met his first wife Eleni Meleagrou, a Greek Cypriot, with whom he has two children, Alexander and Sophia. His son, Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, born in 1984, has worked as a researcher for London think tanks the Policy Exchange and the Centre for Social Cohesion. Hitchens has continued writing essay-style correspondence pieces from a variety of locales, including Chad, Uganda[33] and the Darfur region of Sudan.[34] He has visited all three countries in the so-called "Axis of Evil": Iraq, Iran and North Korea. His work has taken him to over 60 different countries.[35]

In 1989 he met Carol Blue, a Californian writer, whom he later married, and had a daughter, Antonia. In 1991 he received a Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction.[36]

Prior to Hitchens's political shift, the American author and polemicist Gore Vidal was apt to speak of Hitchens as his "Dauphin" or "heir".[37][38][39] In 2010 Hitchens attacked Vidal in a Vanity Fair piece headlined "Vidal Loco", calling him a "crackpot" for his adoption of 11 September conspiracy theories.[40][41]

His strong advocacy of the war in Iraq had gained Hitchens a wider readership, and in September 2005, he was named one of the "Top 100 Public Intellectuals"[42] by Foreign Policy and Prospect magazines. An online poll ranked the 100 intellectuals, but the magazines noted that the rankings of Hitchens (5), Chomsky (1), and Abdolkarim Soroush (15) were partly due to supporters' publicising the vote.[43]

In 2007, Hitchens's work for Vanity Fair won him the National Magazine Award in the category "Columns and Commentary".[44] He was a finalist once more in the same category in 2008 for some of his columns in Slate, but lost out to Matt Taibbi of Rolling Stone.[45]

Views

Literature

Hitchens writes a monthly essay on books in the Atlantic Monthly[46] and contributes occasionally to other literary journals. One of his books, Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere, is a collection of such works, and Love, Poverty and War contains a section devoted to literary essays. In "Why Orwell Matters" he defends Orwell's writings against modern critics as relevant today and progressive for his time. In the 2008 book Christopher Hitchens and His Critics: Terror, Iraq, and the Left, many literary critiques are included of essays and other books of writers such as David Horowitz and Edward Said.

During a three-hour interview by Book TV,[1] he named authors who have had influence on his views.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

Politics

Hitchens became a socialist "largely [as] the outcome of a study of history, taking sides ... in the battles over industrialism and war and empire". In 2001, he told Rhys Southan of Reason magazine that he could no longer say "I am a socialist". Socialists, he claimed, had ceased to offer a positive alternative to the capitalist system. Capitalism had become the more revolutionary economic system, and he welcomed globalisation as "innovative and internationalist". He suggested that he had returned to his early, pre-socialist libertarianism, having come to attach great value to the freedom of the individual from the state and moral authoritarians. The San Francisco Chronicle referred to Hitchens as a "gadfly with gusto".[47] In 2009 Hitchens was listed by Forbes magazine as one of the "25 most influential liberals in the U.S. media."[48] However, the same article noted that he would "likely be aghast to find himself on this list", since it reduces his self-styled radicalism to mere liberalism.

In 2006 in a town hall meeting in Pennsylvania debating the Jewish Tradition with Martin Amis, Hitchens commented on his political philosophy by stating "I am no longer a socialist, but I still am a Marxist".[49] In 2009, in an article for The Atlantic entitled "The Revenge of Karl Marx," Hitchens frames the late-2000s recession in terms of Marx's economic analysis and notes how much Marx admired the capitalist system he was calling for the end of, but says that Marx ultimately failed to grasp how revolutionary capitalist innovation was.[50] Hitchens was and still is a strong admirer of Cuban revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, commenting that "[Che's] death meant a lot to me and countless like me at the time, he was a role model, albeit an impossible one for us bourgeois romantics insofar as he went and did what revolutionaries were meant to do — fought and died for his beliefs."[51] In a 1997 essay, however, he distanced himself somewhat from some of Che's actions.[52]

He continues to regard both Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky as great men,[53][54] and the October Revolution as a necessary event in the modernization of Russia.[18][24] In 2005, Hitchens praised Lenin's creation of "secular Russia" and his destruction of the Russian Orthodox Church, describing it as "an absolute warren of backwardness and evil and superstition."[18] In an interview with Radar in 2007, Hitchens said that if the Christian right's agenda were implemented in the United States "It wouldn't last very long and would, I hope, lead to civil war, which they will lose, but for which it would be a great pleasure to take part."[55]

The years after the fatwa issued against Salman Rushdie also saw him looking for allies and friends. In the United States he became increasingly critical of what he called "excuse making" on the left. At the same time, he was attracted to the foreign policy ideas of some on the Republican right that promoted pro-liberalism intervention, especially the neoconservative group that included Paul Wolfowitz.[56] Around this time, he befriended the Iraqi dissident and businessman Ahmed Chalabi.[57] In 2004, Hitchens stated that neoconservative support for US intervention in Iraq convinced him that he was "on the same side as the neo-conservatives" when it came to contemporary foreign policy issues.[58] He has also been known to refer to his association with "temporary neocon allies".[59]

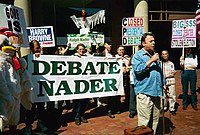

Hitchens would elaborate on his political views and ideological shift in a discussion with Eric Alterman on Bloggingheads.tv. In this discussion Hitchens revealed himself as a supporter of Ralph Nader in the 2000 U.S. presidential election, who was disenchanted with the candidacy of both George W. Bush and Al Gore.[60] Prior to 11 September 2001, and the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, Hitchens was highly critical of Bush's "non-interventionist" foreign policy. He has also criticized Bush's support of intelligent design[61] and capital punishment.[62][62]

Following the 11 September attacks, Hitchens and Noam Chomsky debated the nature of radical Islam and of the proper response to it. On 24 September and 8 October 2001, Hitchens wrote criticisms of Chomsky in The Nation.[63][64] Chomsky responded[65] and Hitchens issued a rebuttal to Chomsky[66] to which Chomsky again responded.[67] Approximately a year after the 11 September attacks and his exchanges with Chomsky, Hitchens left The Nation, claiming that its editors, readers and contributors considered John Ashcroft a bigger threat than Osama bin Laden,[68] and were making excuses on behalf of Islamist terrorism; in the following months he wrote articles increasingly at odds with his colleagues. This highly charged exchange of letters involved Katha Pollitt and Alexander Cockburn, as well as Hitchens and Chomsky.

Hitchens made a brief return to The Nation just before the 2004 U.S. presidential election and wrote that he was "slightly" for George W. Bush; shortly afterwards, Slate polled its staff on their positions on the candidates and mistakenly printed Hitchens' vote as pro-John Kerry. Hitchens shifted his opinion to "neutral", saying: "It's absurd for liberals to talk as if Kristallnacht is impending with Bush, and it's unwise and indecent for Republicans to equate Kerry with capitulation. There's no one to whom he can surrender, is there? I think that the nature of the jihadist enemy will decide things in the end".[69]

Although Hitchens defends Bush’s post-11 September foreign policy, he has criticized the actions and alleged killings of Iraqis by U.S. troops in Abu Ghraib and Haditha, and the U.S. government's use of waterboarding, which he unhesitatingly deemed as torture after being invited by Vanity Fair to voluntarily undergo it.[70][71] In January 2006, Hitchens joined with four other individuals and four organizations, including the ACLU and Greenpeace, as plaintiffs in a lawsuit, ACLU v. NSA; challenging Bush's warrantless domestic spying program; the lawsuit was filed by the ACLU.[72][73][74] In February 2006, Hitchens helped organize a pro-Denmark rally outside the Danish Embassy in Washington, DC in response to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy.[citation needed]

In the 2008 presidential election, Hitchens in an article for Slate would state, 'I used to call myself a single-issue voter on the essential question of defending civilization against its terrorist enemies and their totalitarian protectors, and on that "issue" I hope I can continue to expose and oppose any ambiguity.' He was critical of both main party candidates, Barack Obama and John McCain. Hitchens would go on to support Barack Obama, calling McCain "senile", and his choice of running mate Sarah Palin "absurd", calling Palin a "pathological liar" and a "national disgrace".[75]

Hitchens has described Zionism as being based on "the initial demagogic lie (actually two lies) that a land without a people needs a people without a land." And he went even further saying "Zionism is a form of Bourgeoisie Nationalism" when debating the Jewish Tradition with Martin Amis at a Town hall function in Pennsylvania. "[76] Hitchens supports Israel's right to exist, but has argued against what he calls Israel's "expansionism" in the West Bank and Gaza and "internal clerical and chauvinist forces which want to instate a theocracy for Jews."[77] Hitchens would collaborate on this issue with Edward Said, in 1988 publishing Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question.

Hitchens actively supports drug policy reform and has called for the abolition of the "war on drugs" which he described as an "authoritarian war" during a debate with William F. Buckley.[16] He has supported the legalization of cannabis for both medical and recreational purposes, citing it as a cure for glaucoma and as treatment for numerous side-effects induced by chemotherapy, including severe nausea, describing the prohibition of the drug as "sadistic".[78] On the issue of abortion, Hitchens prioritizes in affirming that he believes a fetus should be regarded as an "unborn child", but opposing the overturning of Roe v. Wade, supporting the development of medical abortion techniques, and fundamentally believing in access to contraceptives and reproductive rights in order to obviate surgical abortion altogether.[79]

Other issues Hitchens has written on include his support for the reunification of Ireland,[80][81] abolition of the British monarchy,[82] and his condemnation of the war crimes of Slobodan Milošević[83] and Franjo Tuđman[84] in Yugoslavia, and the Bosnian War.[85]

Specific individuals

Over the years, Hitchens has become famous for his scathing critiques of public figures. Three figures — Bill Clinton, Henry Kissinger, and Mother Teresa — were the targets of three separate full length texts, No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson Clinton, The Trial of Henry Kissinger, and The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice. Hitchens has also written book-length biographical essays about Thomas Jefferson (Thomas Jefferson: Author of America), George Orwell (Why Orwell Matters) and Thomas Paine (Thomas Paine's "Rights of Man": A Biography).

However, the majority of Hitchens's critiques take the form of short opinion pieces, some of the more notable being his critiques of: Jerry Falwell,[86] George Galloway,[87] Mel Gibson,[88] Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama,[89] Michael Moore,[90] Daniel Pipes,[91] Ronald Reagan,[92] Jesse Helms,[93], and Cindy Sheehan.[18][94][95][96][97][98][99]

Religion

- See also: God is Not Great

Hitchens often speaks out against the Abrahamic religions, or what he calls "the three great monotheisms" (Judaism, Christianity and Islam). In his book, God Is Not Great, Hitchens expanded his criticism to include all religions, including those rarely criticized by Western secularists such as Hinduism and neo-paganism. His book had mixed reactions, from praise in The New York Times for his "logical flourishes and conundrums"[100] to accusations of "intellectual and moral shabbiness" (The Financial Times).[101] God Is Not Great was later nominated for a National Book Award on 10 October 2007.[102][103]

Hitchens contends that organized religion is "the main source of hatred in the world",[104] "[v]iolent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism, tribalism, and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children", and that accordingly it "ought to have a great deal on its conscience." In God Is Not Great, Hitchens contends that;

"above all, we are in need of a renewed Enlightenment, which will base itself on the proposition that the proper study of mankind is man and woman [referencing Alexander Pope]. This Enlightenment will not need to depend, like its predecessors, on the heroic breakthroughs of a few gifted and exceptionally courageous people. It is within the compass of the average person. The study of literature and poetry, both for its own sake and for the eternal ethical questions with which it deals, can now easily depose the scrutiny of sacred texts that have been found to be corrupt and confected. The pursuit of unfettered scientific inquiry, and the availability of new findings to masses of people by electronic means, will revolutionize our concepts of research and development. Very importantly, the divorce between the sexual life and fear, and the sexual life and disease, and the sexual life and tyranny, can now at last be attempted, on the sole condition that we banish all religions from the discourse. And all this and more is, for the first time in our history, within the reach if not the grasp of everyone".[105]

His book made him one of the four major advocates of the "new atheism", and an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society,[106] Hitchens said he would accept an invitation from any religious leader who wished to debate with him. He also serves on the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America,[107] a lobbying group for atheists, agnostics and humanists in Washington, DC. In 2007 Hitchens began a series of written debates on the question "Is Christianity Good for the World?" with Christian theologian and pastor, Douglas Wilson, published in Christianity Today magazine.[108] This exchange eventually became a book by the same title in 2008. During their book tour to promote the book, film producer Darren Doane sent a film crew to accompany them. Doane produced the film Collision: "Is Christianity GOOD for the World?" which was released on 27 October 2009.

Personal life

Consumption of alcohol, tobacco and battle with cancer

A profile on Hitchens by NPR stated: "Hitchens is known for his love of cigarettes and alcohol — and his prodigious literary output."[26] However in early 2008 he gave up smoking, undergoing an epiphany in Madison, Wisconsin.[109] His brother Peter later wrote of his surprise at this decision.[110] Hitchens admits to drinking heavily; in 2003 he wrote that his daily intake of alcohol was enough "to kill or stun the average mule", noting that many great writers "did some of their finest work when blotto, smashed, polluted, shitfaced, squiffy, whiffled, and three sheets to the wind."[111]

Anti-war British politician George Galloway, on his way to testify in front of a United States Senate sub-committee investigating the scandals in the U.N. Oil for Food program, called Hitchens a "drink-sodden ex-Trotskyist popinjay",[112] to which Hitchens quickly replied, "Only some of which is true."[113] Later, in a column for Slate promoting his debate with Galloway which was to take place on 14 September 2005, he elaborated on his prior response: "He says that I am an ex-Trotskyist (true), a "popinjay" (true enough, since its original Webster's definition means a target for arrows and shots), and that I cannot hold a drink (here I must protest)."[114]

Oliver Burkeman writes, "Since the parting of ways on Iraq [...] Hitchens claims to have detected a new, personalised nastiness in the attacks on him, especially over his fabled consumption of alcohol. He welcomes being attacked as a drinker 'because I always think it's a sign of victory when they move on to the ad hominem.' He drinks, he says, 'because it makes other people less boring. I have a great terror of being bored. But I can work with or without it. It takes quite a lot to get me to slur.'"[115]

In an excerpt from his memoir, Hitch-22, published in June 2010, Hitchens wrote: "There was a time when I could reckon to outperform all but the most hardened imbibers, but I now drink relatively carefully." He described his current imbibing routine while he is working as follows: "At about half past midday, a decent slug of Mr. Walker's amber restorative, cut with Perrier water (an ideal delivery system) and no ice. At luncheon, perhaps half a bottle of red wine: not always more but never less. Then back to the desk, and ready to repeat the treatment at the evening meal. No "after dinner drinks"—most especially nothing sweet and never, ever any brandy. "Nightcaps" depend on how well the day went, but always the mixture as before. No mixing: no messing around with a gin here and a vodka there." [116]

On 30 June 2010, Hitchens postponed his book tour from Hitch-22 to undergo treatment for oesophageal cancer.[117]

Relationship with younger brother

Hitchens' younger brother by two-and-a-half years, Peter Hitchens, is a socially conservative journalist in London. The brothers had a protracted falling-out after Peter wrote that Christopher had once joked that he "didn't care if the Red Army watered its horses at Hendon" (a suburb of London).[118] Christopher denied having said this and broke off contact with his brother. He then referred to his brother as "an idiot" in a letter to Commentary, and the dispute spilled into other publications as well. Christopher eventually expressed a willingness to reconcile and to meet his new nephew; shortly thereafter the brothers gave several interviews together in which they said their personal disagreements had been resolved. They appeared together on the 21 June 2007 edition of BBC current affairs discussion show Question Time. The pair engaged in a formal televised debate for the first time on 3 April 2008, at Grand Valley State University.[119]

Film and television appearances

As referenced from the Internet Movie Database or Hitchens Web.[120][121]

| Year | Film |

|---|---|

| 1984 | Opinions: "Greece to their Rome" |

| 1993 | Everything You Need to Know |

| 1994 | Tracking Down Maggie: The Unofficial Biography of Margaret Thatcher |

| 1994 | Hell's Angel |

| 1998 | Princess Diana: The Mourning After |

| 1999–2002 | Dennis Miller Live (4 episodes) |

| 2002 | The Trials of Henry Kissinger |

| 2003 | Hidden in Plain Sight |

| 2004 | Mel Gibson: God's Lethal Weapon |

| 2005 | Penn & Teller: Bullshit! (1 episode) |

| 2005 | The Al Franken Show (1 episode) |

| 2005 | Confronting Iraq: Conflict and Hope |

| 2005 | Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism |

| 2004–2006 | Newsnight (3 episodes) |

| 2006 | American Zeitgeist |

| 2006 | Blog Wars |

| 2007 | Manufacturing Dissent |

| 2004–2007 | The Daily Show (3 episodes) |

| 2007 | Question Time (1 episode) |

| 2007 | Your Mommy Kills Animals |

| 2007 | Personal Che |

| 2007 | Heckler |

| 2008 | Discussions with Richard Dawkins: Episode 1: "The Four Horsemen" |

| 2005–2008 | Hardball with Chris Matthews (3 episodes) |

| 2009 | Holy Hell |

| 2009 | Presidency |

| 2003–2009 | Real Time with Bill Maher (6 episodes) |

| 2009 | Collision: "Is Christianity GOOD for the World?" |

| 2010 | The Daily Show With Jon Stewart |

In May 2009, Hitchens expressed interest in adapting God is Not Great into a feature documentary, aspiring to be "tougher and funnier" than Bill Maher's 2008 film Religulous.[122]

Bibliography

- 1987 Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles, Chatto and Windus (UK)/Hill and Wang (US, 1988) / 1997 UK Verso edition as The Elgin Marbles: Should They Be Returned to Greece? (with essays by Robert Browning and Graham Binns)

- 1988 Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question (contributor; co-editor with Edward Said) Verso, ISBN 0-86091-887-4 Reissued, 2001

- 1995 The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, Verso

- 2000 Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere, Verso

- 2001 Letters to a Young Contrarian, Basic Books

- 2004 Love, Poverty, and War: Journeys and Essays, Thunder's Mouth, Nation Books, ISBN 1-56025-580-3

- 2005 Thomas Jefferson: Author of America, Eminent Lives/Atlas Books/HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN 0-06-059896-4

- 2007 The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Non-Believer, [Editor] Perseus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6

- 2007 God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, Twelve/Hachette Book Group USA/Warner Books, ISBN 0-446-57980-7 / Published in the UK as God Is Not Great: The Case Against Religion, Atlantic Books, ISBN 978-1-84354-586-6

- 2008 Christopher Hitchens and His Critics: Terror, Iraq and the Left (with Simon Cottee and Thomas Cushman), New York University Press

- 2008 Is Christianity Good for the World? – A Debate (co-author, with Douglas Wilson), Canon Press, ISBN 1-59128-053-2

- 2010 Hitch-22 Some Confessions and Contradictions: A Memoir, Hachette Book Group, ISBN 978-0-446-54033-9

References

- ^ a b c Christopher Hitchens In Depth Book TV, 2 September 2007 - List of writers can be seen @ 1:13:10

- ^ "Tariq Ali v. Christopher Hitchens". Democracy Now. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ "The Situation Room, Nov. 1, 2006". CNN. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ "The big showdown: Andrew Anthony on Hitchens v Galloway". London: The Guardian. 18 September 2005. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ Andre Mayer (14 May 2007). "Nothing sacred — Journalist and provocateur Christopher Hitchens picks a fight with God". CBC. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ^ "God Is Not Great" author, Christopher Hitchens talks about religion, politics, and becoming an American Greater Talent Network, 10 July 2007

- ^ The William And Barbara Edwards Media Fellows Program Hoover Institution

- ^ Hitch-22: A Memoir (Hardcover) Amazon.com product information page: Hitch-22: A Memoir. An edition was published in Australia by Allen and Unwin in May: ISBN 978-1-74175-962-4

- ^ Christopher Hitchens to Begin Cancer Treatment by Jeremy Peters, The New York Times, 30 June 2010

- ^ a b Look who's talking The Observer, 14 April 2002

- ^ a b c d Walsh, John. The Independent. "Hitch-22: a memoir by Christopher Hitchens" Retrieved 28 May 2010

- ^ Lynn Barber Look who's talking The Observer, 14 April 2002

- ^ Blake Morrison I contain multitudes, The Guardian, 29 May 2010

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher, Hitch-22 (Allen & Unwin, 2010) p. 76 ff.

- "How Christopher Hitchens Was Forced to Be Apart From His Prep School Boyfriend", Queerty, 29 March 2010, accessed 30 May 2010

- ^ Levy, Geoffery, "So Who Were the Two Tory Ministers Who Had Gay Flings with Christopher Hitchens at Oxford?", Daily Mail, 6 March 2010, accessed 30 May 2010

- ^ a b Hoover Institution[dead link]

- ^ Long Live Labor - Why I'm for Tony Blair Slate, 25 April 2005

- ^ a b c d Heaven on Earth - Interview with Christopher Hitchens PBS, 2005

- ^ International Socialism: Christopher Hitchens "Workers’ Self Management in Algeria" (1st series), No.51, April-June 1972, p.33 Encyclopedia of Trotskyism, 25 October 2005

- ^ Alexander Linklater (May 2008). "Christopher Hitchins". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Barber, Lynn (13 April 2002). "Look who's talking". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ For the Sake of Argument by Christopher Hitchens Interview with Brian Lamb for the show Booknotes, an author interview series on C-SPAN (some biographical information) 17 October 1993

- ^ The Boy Can't Help It In-depth interview and profile] in New York Magazine, 19 April 1999

- ^ a b c "Free Radical", interview in Reason by Rhys Southan, November 2001

- ^ Christopher Hitchens Atlantic Monthly, 2003

- ^ a b Guy Raz, Christopher Hitchens, Literary Agent Provocateur, National Public Radio, 21 June 2006

- ^ He Knew He Was Right New Yorker, Profiles, 16 October 2006

- ^ Christopher Hitchens Notable Interviews - video interview 2007

- ^ Christopher Hitchens - Contributing Editor Vanity Fair

- ^ Timothy Noah, Meritocracy's lab rat Slate, 9 January 2002

- ^ Annabel's – the magazine Vogue UK, 15 July 2004

- ^ At the Rom: Three New Commandments She Does The City, 30 April 2009

- ^ "Childhood's End", Vanity Fair, September 2006

- ^ "Realism in Sudan", Slate, 7 November 2005

- ^ Christopher Hitchens Twelve Publishers

- ^ Detailed Biographical Information - Christopher Hitchens, Lannan Foundation; Retrieved 27 April 2010

- ^ Andrew Werth (January/February 2004). "Hitchens on Books". Letters to the Editor. The Atlantic. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ John Banville (3 March 2001). "Gore should be so lucky". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Gore Vidal on Christopher Hitchens YouTube

- ^ Christopher Hitchens (February 2010). "Vidal Loco". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Youde, Kate (7 February 2010). "Hitchens attacks Gore Vidal for being a 'crackpot'". London: The Independent. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Prospect/FP Top 100 Public Intellectuals Results Foreign Policy, registration required

- ^ The Prospect/FP Top 100 Public Intellectuals Foreign Policy, registration required

- ^ 2007 National Magazine Award Winners Announced Press release, Magazine Publishers of America, 1 May 2007

- ^ National Magazine Awards Winners and Finalists Magazine Publishers of America

- ^ Authors - Christopher Hitchens The Atlantic

- ^ FIVE QUESTIONS FOR: Christopher Hitchens SF Gate

- ^ "The 25 Most Influential Liberals In The US Media". Forbes.com. 22 January 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ Martin Amis Christopher Hitchens a conversation about Antisemitism and Saul bellow Part 3 YouTube

- ^ The Revenge of Karl Marx The Atlantic, April 2009

- ^ Just a Pretty Face? The Guardian, 11 July 2004

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (1997), “Goodbye to All That”, The New York Review of Books, 17 July 1997

- ^ Amis, Martin (2002). Koba the Dread. Miramax. p. 25. ISBN 0786868767.

- ^ "Great Lives - Leon Trotsky", BBC Radio 4, 8 August 2006

- ^ Godless Provocateur Christopher Hitchens Pledges Allegiance to America

- ^ "That Bleeding Heart Wolfowitz", Slate, 22 March 2005

- ^ "Ahmad and Me", Slate, 27 May 2004

- ^ Johann Hari, "In Enemy Territory: An Interview with Christopher Hitchens"", The Independent, 23 September 2004.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens, "The End of Fukuyama", Slate, 1 March 2006

- ^ On Whether Christopher Hitchens Was Wrong Bloggingheads.tv, 14 October 2008

- ^ Belz, Mindy. "According to Hitch", World Magazine, 3 April 2006

- ^ a b "A War To Be Proud Of" Weekly Standard, 5 September 2005

- ^ Of Sin, the Left & Islamic Fascism The Nation, 4 September 2001

- ^ Blaming bin Laden First The Nation, 4 October 2001

- ^ Chomsky Replies to Hitchens[dead link]

- ^ A Rejoinder to Noam Chomsky: Minority Report The Nation, 2001

- ^ Reply to Hitchens's Rejoinder The Nation, 4 October 2001

- ^ Taking Sides The Nation, 26 September 2002

- ^ My Endorsement and Osama's Video: The news in Bin Laden's comments had nothing to do with our election Slate, 1 November 2004]

- ^ "Believe Me, It’s Torture", Vanity Fair, August 2008

- ^ On the Waterboard Vanity Fair, 2 July 2008

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric. "Two Groups Planning to Sue Over Federal Eavesdropping" The New York Times, 17 January 2006; Retrieved on 5 November 2009

- ^ Statement – Christopher Hitchens, NSA Lawsuit Client

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (7 August 1999). "Gov. Death". Salon.com. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher "Vote for Obama" Slate, 13 October 2008; Retrieved on 5 November 2009

- ^ "Frontpage Interview: Christopher Hitchens Part II". Front Page Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ "Arafat's Squalid End". Slate. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Just a Pretty Face? by Sean O'Hagan, The Observer, 11 July 2004

- ^ Belief Watch: Pro-life Atheists NewsWeek

- ^ Galloway vs. Hitchens: The Transcript endusmilitarism, 16 September 2005

- ^ These Men Are "Peacemakers"? Ian Paisley and Gerry Adams make me want to spew Slate, 2 April 2007

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher End of the line The Guardian, 6 December 2000

- ^ "In Defense of WWII: Chapter 5 of 5". Youtube. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ "Shed No Tears for Milosevic". FrontPage Magazine. 14 March 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ Bodansky, Yossef (1996). Some Call It Peace: Waiting for the War In the Balkans. International Media Corp. Ltd. ISBN 0952007053.

- ^ Video: Christopher Hitchens (15 May 2007) appearance on Anderson Cooper 360 YouTube

- ^ Unmitigated Galloway Weekly Standard, 30 May 2005

- ^ Mel Gibson's Meltdown Slate, 31 July 2006

- ^ His material highness Salon.com article by Christopher Hitchens

- ^ Unfairenheit 9/11 Slate, 21 June 2004

- ^ Christopher Hitchens "Daniel Pipes is not a man of peace", Slate, 11 August 2003

- ^ "The stupidity of Ronald Reagan". Slate. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens "Farewell to a Provincial Redneck" Slate, 7 July 2008

- ^ Christopher Hitchens, Cindy Sheehan's Sinister Piffle, Slate, 15 August 2005

- ^ Mommie Dearest Slate, 20 October 2003 - Hitchens's op-ed for Slate regarding Mother Theresa

- ^ Living in Thomas Jefferson's Fictions NPR, 1 June 2005 - Hitchens's NPR discussion regarding Thomas Jefferson

- ^ Why Orwell Still Matters BBC News, 3 July 2002 - Hitchens' BBC Video Essay in support of George Orwell

- ^ Transcript: Bill Moyers Talks with Christopher Hitchens PBS, 20 December 2002

- ^ Edward Luce (11 January 2008). "Lunch with the FT: Christopher Hitchens". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Michael Kinsley In God, Distrust New York Times Book Review, 13 May 2007

- ^ Here’s the hitch by Michael Skapinker in The Financial Times

- ^ Associated Press[dead link]

- ^ Hardcover Nonfiction New York Times Bestseller list, 3 June 2007

- ^ Free Speech onegoodmove, March 2007

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (2007). God is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. New York: Twelve Books. p. 283.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Honorary Associate: Christopher Hitchens National Secular Society

- ^ Biography - Christopher Hitchens Secular Coalition for America Advisory Board

- ^ "Is Christianity Good for the World?" Christianity Today, 8 May 2007

- ^ Edward Luce, Lunch with the Financial Times, 11 January 2008

- ^ Hitchens, Peter (5 April 2008). "Hitchens vs Hitchens ... Peace at last as a lifelong feud between brothers is laid to rest". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens, Living Proof, Vanity Fair, March 2003

- ^ Unmitigated Galloway , The Weekly Standard, 30 May 2005

- ^ "There's only one popinjay here, George", Evening Standard, 19 May 2005

- ^ George Galloway Is Gruesome, Not Gorgeous, Slate, 13 September 2005

- ^ Oliver Burkeman, War of words, The Guardian, 28 October 2006

- ^ A Short Footnote on the Grape and the Grain, Slate, 06 June 2010

- ^ [1], "Washington Post", 30 June 2010

- ^ Christopher Hitchens,Oh Brother, Where Art Thou The Spectator, 12 October 2001, from FindArticles.com

- ^ "Hitchens v. Hitchens: Faith, Politics & War". Grand Valley State University. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ^ "Christopher Hitchens". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "Hitchens Web". Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens on The Hour (Part 2 of 2) YouTube

External links

Articles by Hitchens

- Contributor page for Vanity Fair

- Index at The Atlantic Monthly

- Christopher Hitchens Blog The Mirror (British tabloid)

- Hitchens Web

- Build Up That Wall – Christopher Hitchens online directory

- Hitchens articles at Slate

Interviews

- The World According to Christopher Hitchens, a video collection of various appearances by Hitchens, hosted by FORA.tv.

- Video debate/discussion "On Whether Christopher Hitchens Was Wrong" (about many things) between Hitchens and Eric Alterman on Bloggingheads.tv

- Christopher Hitchens at Politics and Prose on Fora.tv, 10 May 2007

- Uncommon Knowledge: Christopher Hitchens

- Q&A: Christopher Hitchens, C-SPAN, YouTube, 27 April 2009 (56 min 56 sec)

- Christopher Hitchens on freedom of expression

- "The War on Terror Revisited" - FCE

- Stephen Capen interview on Worldguide Futurist Radio Hour, 24 December 1995

- "Christopher Hitchens: 'I was right and they were wrong'" The Guardian, 22 May 2010

- On Hitch-22 at the New York Public Library, June 4, 2010

Debates

- Christopher Hitchens and Douglas Wilson

- Christopher Hitchens and Peter Hitchens

- Hitchens and Turek on "Does God Exist"

- The Hitchens-Wilson Debate, a written debate in which Hitchens debates with theologian Douglas Wilson Is Christianity is good for the world?

- Christopher Hitchens and Al Sharpton on Fora.tv, 7 May 2007

Profiles

- "Christopher Hitchens" feature story in Prospect magazine, May 2008

- "Incendiary Author Spares No Targets" feature story in The New Zealand Herald, May 2008

- Such, Such are His Joys David Brooks assessment in The New York Times, 1 July 2010

Reviews

- Review of Hitchens' A Long Short War, Bully Magazine, 15 April 2004

- Review of Hitchens' Hitch-22: A Memoir, New York Times, 10 June 2010

- 1949 births

- Living people

- People from Portsmouth

- Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

- American atheists

- American biographers

- American essayists

- American secular humanists

- American journalists

- American Marxists

- American media critics

- American political pundits

- American political writers

- Anti-Vietnam War activists

- Atheism activists

- American people of British descent

- British political pundits

- British republicans

- Cancer patients

- Criticism of Islam

- Criticism of religion

- Contributors to Bloggingheads.tv

- Drug policy reform activists

- American people of English descent

- English atheists

- English-American Jews

- English Marxists

- English biographers

- English essayists

- English humanists

- English journalists

- English immigrants to the United States

- English people of Polish descent

- English people of German descent

- English political writers

- Genital integrity activists

- Jewish atheists

- Marxist journalists

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Old Leysians

- Slate magazine people

- Socialist Workers Party (Britain) members

- The Nation (U.S. periodical) people

- Lecturers

- University Challenge contestants