Rigveda

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

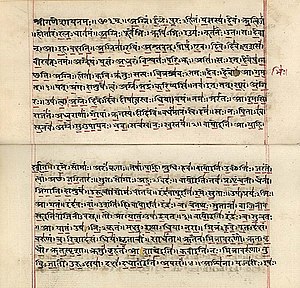

The Rigveda (Sanskrit: ऋग्वेद ṛgveda, a tatpurusha compound of ṛc "praise, verse" and veda "knowledge") is a collection of hymns (ṛc, plural ṛcas) counted among the four Hindu religious texts known as the Vedas, and contains the oldest texts preserved in any Indo-Iranian language. Its core is accepted to date to the late Bronze Age, making it the only example of Bronze Age literature with an unbroken tradition: All other texts of similar or greater age are known from archaeological excavations only.

It consists of 1,017 hymns (1,028 including the apocryphal valakhīlya hymns 8.49–8.59) composed in Vedic Sanskrit, many of which are intended for various sacrifical rituals. These are contained in 10 books, known as Mandalas. This long collection of short hymns is mostly devoted to the praise of the gods. However, it also contains fragmentary references to historical events, notably the struggle between the early Vedic people (known as Vedic Aryans, a subgroup of the Indo-Aryans) and their enemies, the Dasa.

The chief gods of the Rigveda are Agni, the sacrificial fire, Indra, a heroic god that is praised for having slain his enemy Vrtra, and Soma, the sacred potion, or the plant it is made from. Other prominent gods are Mitra, Varuna and Ushas (the dawn). Also invoked are Savitar, Vishnu, Rudra, Pushan, Brihaspati, Brahmanaspati, Dyaus Pita (the sky), Prithivi (the earth), Surya (the sun), Vayu (the wind), Parjanya (the rain), Vac (the word), the Maruts, the Asvins, the Adityas, the Rbhus, the Vishvadevas (the all-gods) as well as various further minor gods, persons, concepts, phenomena and items.

Some of the names of gods and goddesses found in the Rigveda are found amongst other Indo-European people as well: Dyaus-Pita is cognate with Greek Zeus, Latin Jupiter (from deus-pater), and Germanic Tyr; while Mitra is cognate with Persian Mithra; also, Ushas with Greek Eos and Latin Aurora; and, less certainly, Varuna with Greek Uranos. Finally, Agni is cognate with Latin ignis and Russian ogon, both meaning "fire".

Text

From the time of its compilation (redaction), the text has been handed down in two versions: The Samhitapatha has all Sanskrit rules of sandhi applied and is the text used for recitation. The Padapatha has each word isolated in its pausa form and is used for memorization. The Padapatha is, as it were, a commentary to the Samhitapatha, but the two seem to be about co-eval. The original text as reconstructed on metrical grounds lies somewhere between the two, but closer to the Samhitapatha ("original" in the sense that it aims to recover the hymns in the form of their composition by the poets, known as Rishis).

Hermann Grassmann has numbered the hymns 1 through to 1028, putting the valakhilya at the end. The more common numbering scheme is by book, hymn and verse (and pada (foot) a, b, c ..., if required). E. g. the first pada is

- 1.1.1a agním īḷe puróhitaṃ "Agni I laud, the high priest"

and the final pada is

- 10.191.4d yáthāḥ vaḥ súsahā́sati "for your being in good company"

The entire 1028 hymns of the Rigveda, in the 1877 edition of Aufrecht, contain a total 39,831 padas. Counting the number of syllables is less straightforward because of issues of sandhi, but the metrical text of van Nooten and Holland (1994) has a total of 395,563 syllables (or an average of 9.93 syllables per pada). Most verses are jagati (padas of 12 syllables), trishtubh (padas of 11 syllables), viraj (padas of 10 syllables) or gayatri or anushtubh (padas of 8 syllables). The Shatapatha Brahmana gives a higher number of syllables, 432,000.

The Rigveda is preserved by two major shakhas ("branches", i. e. schools or recensions), Śākala and Bāṣkala. Considering its great age, the text is spectacularly well preserved and uncorrupted, the two recensions being practically identical, so that scholarly editions can mostly do without a critical apparatus. Associated to Śākala is the Aitareya-Brahmana. The Bāṣkala includes the Khilani and has the Kausitaki-Brahmana associated to it.

Books

Linguistic (as well as content-related) evidence suggests that books 2-7 are older than the remaining books. Books 1 and 10 are considered the most recent.

- Book 1

- 191 hymns. Hymn 1.1 is addressed to Agni, arranged so that the name of this god is the first word of the Rigveda. The remaining hymns are mainly addressed to Agni and Indra. Hymns 1.154 to 1.156 are addressed to (the later Hindu god) Vishnu.

- Book 2

- Book 3

- 62 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra. The verse 3.62.10 gained great importance in Hinduism as the Gayatri Mantra. Most hymns in this book are attributed to viśvāmitra gāthinaḥ

- Book 4

- Book 5

- 87 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra, the Visvadevas, the Maruts, the twin-deity Mitra-Varuna and the Asvins. Two hymns each are dedicated to Ushas (the dawn) and to Savitar. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the atri family

- Book 6

- 75 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the bārhaspatya family of Angirasas.

- Book 7

- 104 hymns, to Agni, Indra, the Visvadevas, the Maruts, Mitra-Varuna, the Asvins, Ushas, Indra-Varuna, Varuna, Vayu (the wind), two each to Sarasvati and Vishnu, and to others. Most hymns in this book are attributed to vasiṣṭha maitravaurṇi

- Book 8

- 103 hymns, mixed gods. Hymns 8.49 to 8.59 are the apocryphal valakhīlya, the majority of them are devoted to Indra. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the kāṇva family

- Book 9

- 114 hymns, entirely devoted to Soma Pavamana, the plant of the sacred potion of the Vedic religion.

- Book 10

- 191 hymns, to Agni and other gods. In the west, probably the most celebrated hymns are 10.129 and 10.130 dealing with creation, especially 10.129.7:

- He, the first origin of this creation, whether he formed it all or did not form it, / Whose eye controls this world in highest heaven, he verily knows it, or perhaps he knows not. (Griffith)

- These hymns exhibit a level of philosophical speculation very atypical of the Rig-Veda, which for the most part is occupied with ritualistic invocation.

Translations

The Rigveda was translated into English by Ralph T.H. Griffith in 1896. Partial English translations by Maurice Bloomfield and William Dwight Whitney exist. Griffith's translation is good, considering its age, but it is no replacement for Geldner's 1951 translation, the only independent scholarly translation so far. The later translations by Langlois and Elizarenkova depend heavily on Geldner, but Elizarenkova's translation is valuable in taking into account scholarly literature up to 1990.

Internal evidence

The Rigveda is far more archaic than any other Indo-Aryan text preserved. For this reason, it has been in the center of attention of western scholarship from the times of Max Müller. The Rigveda records an early stage of Vedic religion, still closely tied to the pre-Zoroastrian Persian religion. It is thought that Zoroastrianism and Vedic Hinduism evolved from an earlier common religious Indo-Iranian culture.

Scholars usually date the Rigveda to the 2nd millennium BC both linguistically and on grounds of its references to late bronze age culture. The Rigveda describes a mobile, nomadic culture, with horse-drawn chariots and metal (bronze) weapons. According to some scholars the geography described is consistent with that of the Punjab (Gandhara): Rivers flow north to south, the mountains are relatively remote but still reachable (Soma is a plant found in the mountains, and it has to be purchased, imported by merchants). D.B. Kasar identifies the Sahyadri mountains in Maharashtra with rivers Vedganga, Pravara, Vashisthi, Neera, Sindphana as a possible location, though this claim is not widely accepted.

The text is commonly held to have been completed between 1500 BC and 1200 BC, or the early period of the Gandhara Grave culture. After their composition, the texts were preserved and codified by a vast body of Vedic priesthood as the central philosophy of the Iron Age Vedic civilization.

Nevertheless, the hymns were certainly composed over a long period, with the oldest elements possibly reaching back into Indo-Iranian times, or the early 2nd millennium BC. Thus there is some debate over whether the boasts of the destruction of stone forts by the Vedic Aryans and particularly by Indra refer to cities of the Indus Valley civilization or whether they hark back to clashes between the early Indo-Aryans with the BMAC (Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex) culture centuries earlier, in what is now northern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan (separated from the upper Indus by the Hindu Kush mountain range, and some 400 km distant). In any case, while it is highly likely that the bulk of the Rigveda was composed in the Punjab, even if based on earlier poetic traditions, there is no mention of either tigers or rice in the Rigveda (as opposed to the later Vedas), suggesting that Vedic culture only penetrated into the plains of India after its completion. Similarly, there is no mention of iron. The Iron Age in northern India begins in the 12th century BC with the Black and Red Ware (BRW) culture. This is a widely accepted timeframe for the beginning codification of the Rigveda (i.e. the arrangement of the individual hymns in books, and the fixing of the samhitapatha (by applying Sandhi) and the padapatha (by dissolving Sandhi) out of the earlier metrical text), and the composition of the younger Vedas. This time probably coincides with the early Kuru kingdom, shifting the center of Vedic culture east from the Punjab into what is now Uttar Pradesh.

Some, mostly Indian, writers have used alleged astronomical references in the Rigveda to date it to as early as the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship widely rejects these interpretations as pseudoscientific (e.g. Witzel, 1999).

Hindu tradition

According to Indian tradition, the Rigvedic hymns were collected by Paila under the guidance of Vyāsa, who formed the Rigveda Samhita as we know it. According to the Śatapatha Brāhmana, the number of syllables in the Rigveda is 432,000, equalling the number of muhurtas (1 day = 30 muhurtas) in forty years. This statement stresses the underlying philosophy of the Vedic books that there is a connection (bandhu) between the astronomical, the physiological, and the spiritual.

The authors of the Brāhmana literature described and interpreted the Rigvedic ritual. Yaska was an early commentator of the Rigveda. In the 14th century, Sāyana wrote an exhaustive commentary on it. Other Bhāṣyas (commentaries) that have been preserved up to present times are those by Mādhava, Skaṃdasvāmin and Veṃkatamādhava.

More recent Indian views

Generally speaking, the Indian perception of the Rigveda has moved away from the original ritualistic content to a more symbolic or mystical interpretation. For example, instances of animal sacrifice are not seen as literal slaughtering but as transcendental processes. The Rigvedic view is seen to consider the universe to be infinite in size, dividing knowledge into two categories: lower (related to objects, beset with paradoxes) and higher (related to the perceiving subject, free of paradoxes). Swami Dayananda, who started the Arya Samaj and Sri Aurobindo have emphasized a spiritual (adhyatimic) interpretation of the book.

The Sarasvati river, lauded in RV 7.95 as the greatest river flowing from the mountain to the sea is sometimes equated with the Ghaggar-Hakra river, which went dry perhaps before 2600 BC or certainly before 1900 BC. Others argue that the Sarasvati was originally the Helmand in Afghanistan. These questions are tied to the debate about the Indo-Aryan migration (termed "Aryan Invasion Theory") vs. the claim that Vedic culture together with Vedic Sanskrit originated in the Indus Valley Civilisation, a topic of great significance in Hindu nationalism, addressed for example by Amal Kiran and Shrikant G. Talageri. Subhash Kak has claimed that there is an astronomical code in the organization of the hymns. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, based on alleged astronomical alignments in the Rig-Veda, even went as far as to claim that the Aryans originated on the North Pole (Arctic Home in the Vedas, 1903). D. B. Kasar compares the Indus script to Germanic runes and claims that IVC inscriptions contain Rigvedic hymns.

References

- Michael Witzel, The Pleiades and the Bears viewed from inside the Vedic texts, EVJS Vol. 5 (1999), issue 2 (December) [1].

Editions

- Friedrich Max Müller, The Hymns of the Rigveda, with Sayana's commentary, London, 1849-75, 6 vols., 2nd ed. 4 vols., Oxford, 1890-92.

- Theodor Aufrecht, 2nd ed., Bonn, 1877.

- B. van Nooten und G. Holland, Rig Veda, a metrically restored text, Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 1994.

Translations

- English

- Ralph T.H. Griffith, Hymns of the Rig Veda (1896)

- German

- Karl Friedrich Geldner, Der Rig-Veda: Aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche übersetzt Harvard Oriental Studies, vols. 33, 34, 35 (1951), reprint Harvard University Press (2003) ISBN 0674012267

- French

- A. Langlois, Paris 1984 (2nd ed.) ISBN 2720010294

- Russian

- Tatyana Ya. Elizarenkova, Nauka, Moscow 1989-1999.

Bibliography

Commentary

- Sayana (14th century), ed. Müller 1849-75

- Sri Aurobindo: Hymns of the Mystic Fire (Commentary on the Rig Veda), Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, Wisconsin ISBN 0-914955-22-5 [2]

Western philology

- Oldenberg, Hermann: Hymnen des Rigveda. 1. Teil: Metrische und textgeschichtliche Prolegomena. Berlin 1888; Wiesbaden 1982.

- — Die Religion des Veda. Berlin 1894; Stuttgart 1917; Stuttgart 1927; Darmstadt 1977

- — Vedic Hymns, The sacred books of the East vo,l. 46 ed. Friedrich Max Müller, Oxford 1897

Hindu Historical, Archaeoastronomy etc.

- Frawley David: The Rig Veda and the History of India, 2001.(Aditya Prakashan), ISBN 81-7742-039-9

- Talageri, Shrikant: The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, ISBN 81-7742-010-0

- Kak, Subhash: The Astronomical Code of the Rigveda, Delhi, Munshiram Manoharlal, 2000, ISBN 81-215-0986-6.

- Tilak, Bal Gangadhar: The Artic Home of the Vedas

External links

Text