Tala (music)

Tāla or Taal (Sanskrit tālà, literally a "clap", also transliterated as "tala") is the term used in Indian classical music for the rhythmic pattern of any composition and for the entire subject of rhythm, roughly corresponding to metre in Western music, though closer conceptual equivalents are to be found in other Asian classical systems such as the notion of usul in the theory of Ottoman/Turkish music.

Rhythm in Indian music performs the function of a time counter. A taal is a rhythmic cycle of beats with an ebb and flow of various types of intonations resounded on a percussive instrument. Each such pattern has its own name. Indian classical music has complex, all-embracing rules for the elaboration of possible patterns, though in practice a few taals are very common while others are rare. The most common taal in Hindustani classical music is Teental, a cycle of four measures of four beats each.

A taal does not have a fixed tempo and can be played at different speeds. In Hindustani classical music a typical recital of a raga falls into two or three parts categorized by the tempo of the music - Vilambit laya (Slow tempo), Madhya laya (Medium tempo) and Drut laya (Fast tempo). In Carnatic Music, there are five categories of tempo namely - Chauka (1 stroke per beat), Vilamba (2 strokes per beat), Madhyama(4 beats per beat), Dhuridha(8 strokes per beat), Adi-Dhuridha(16 strokes per beat). But, although the tempo changes, the fundamental rhythm does not.

Each repeated cycle of a taal is called an avartan. A tala is generally divided into sections (vibhaags), not all of which may have the same number of beats.

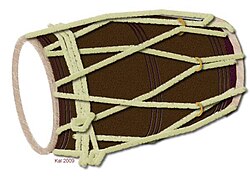

The most common instrument for keeping rhythm in Hindustani music is the tabla, while in Carnatic music, it is the mridangam (which is also transliterated as mridang).

Tala in Carnatic music

Carnatic music uses a comprehensive system for the specification of talas, called the suladi sapta tala system. According to this system, there are seven families of talas, each of which has five members, one each of five types or varieties (jati or chapu), thus allowing thirty-five possible talas.

In Carnatic music each pulse count is called an aksharam or a kriyā, the interval between each being equal, though capable of division into faster matras or svaras, the fundamental unit of time. The tala is defined by the number and arrangement of aksharams inside an avartanam. There are three sub-patterns of beats into which all talas are divided; laghu, dhrutam and anudhrutam.

- A dhrutam is a pattern of 2 beats. This is notated 'O'.

- An anudhrutam is a single beat, notated 'U'.

- A laghu is a pattern with a variable number of beats, 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9, depending upon the type of the tala. It is notated '1'. The number of matras in an aksharam is called the nadai or jati. This number can be 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9, and these types are respectively called Tisra, Chatusra, Khanda, Misra and Sankeerna. The default jati is Chatusram:

| Jati | Aksharams in laghu | Phonetic representation of beats |

| Tisra | 3 | Tha Ki Ta |

| Chatusra | 4 | Tha Ka Dhi Mi |

| Khanda | 5 | Tha Ka Tha Ki Ta |

| Misra | 7 | Tha Ki Ta Tha Ka Dhi Mi |

| Sankeerna | 9 | Tha Ka Dhi Mi Tha Ka Tha Ki Ta |

The seven families are:

| Tala | Description of avartanam | Default length of laghu | Total Aksharas according to the Saptha Alankaras |

| Dhruva | 1O11 | 4 | 14 |

| Matya | 1O1 | 4 | 10 |

| Rupaka | O1 | 4 | 6 |

| Jhampa | 1UO | 7 | 10 |

| Triputa | 1OO | 3 | 7 |

| Ata | 11OO | 5 | 14 |

| Eka | 1 | 4 | 4 |

For instance one avartanam of Khanda-jati Rupaka tala comprises a 2-beat dhrutam followed by a 5-beat laghu. An avartanam is thus 7 aksharams long. With all possible combinations of tala types and laghu lengths, there are 5 x 7 = 35 talas having lengths ranging from 3 (Tisra-jati Eka) to 29 (sankeerna-jati Dhruva) aksharams. Chatusra-gati Khanda-jaati Rupaka tala has 7 aksharam, each of which is 4 matras long; each avartanam of the tala is 4 x 7 = 28 matras long. For Misra-gati Khanda-jati Rupaka tala, it would be 7 x 7 = 49 matra.

In practice, only a few talas have compositions set to them. As in the table above, each variety of tala has a default family associated with it; the variety mentioned without qualification refers to the default. For instance, Jhampa tala is Misra-jati Jhampa tala [1].

The most common tala is Chatusra-nadai Chatusra-jaati Triputa tala, also called Adi tala (Adi meaning primordial in Sanskrit). From the above tables, this tala has eight aksharams, each being 4 svarams long. Many kritis and around half of the varnams are set to this tala. Other common talas include:

- Chatusra-nadai Chatusra-jaati Rupaka tala (or simply Rupaka tala) [1]. A large body of krtis is set to this tala.

- Khanda Chapu (a 10-count) and Misra Chapu (a 14-count), both of which do not fit very well into the suladi sapta tala scheme. Many padams are set to Misra Chapu, while there are also krtis set to both the above talas.

- Chatusra-nadai Khanda-jati Ata tala (or simply Ata tala) [1]. Around half of the varnams are set to this tala.

- Tisra-nadai Chatusra-jati Triputa tala (Adi Tala Tisra-Nadai) [1]. A few fast-paced kritis are set to this tala. Note that, as this tala is a twenty-four beat cycle, compositions in this tala theoretically can, and sometimes are, sung in rupaka tala.

Sometimes, pallavis are sung as part of a Ragam Thanam Pallavi exposition in some of the rarer, more complicated talas; such pallavis, if sung in a non-Chatusra-nadai tala, are called nadai pallavis. In addition, pallavis are often sung in chauka kale(slowing the tala cycle by a magnitude of four times), although this trend seems to be slowing.

Eduppu or Start point

Compositions do not always begin on the first beat of the tala: it may be offset by a certain number of matras or aksharas or combination of both to suit the words of the composition. The word Talli, used to describe this offset, is from Tamill and literally means "shift". A composition may also start on one of the last few matras of the previous avartanam. This is called Ateeta Eduppu.

Taal in Hindustani Music

See also: Taals in Sikh Kirtan

Taals have a vocalised and therefore recordable form wherein individual beats are expressed as phonetic representations of various strokes played upon the tabla. The first beat of any taal, called sam (pronounced as the English word 'sum' and meaning even or equal, archaically meaning nil) is denoted with an 'X'. The first beat is always the most important and heavily emphasised. It is also the point of resolution in the rhythm. A soloist has to sound an important note of the raag there, and the percussionist's and soloist's phrases culminate at that point. A North Indian classical dance composition must end on the sam.

The beats of a taal are divided into groups known as vibhaags, the first beat of each vibhaag usually being accented. It is this that gives the taal its unique texture. For example, Rupak taal consists of 7 beats while the related Dhamar taal consists of 14 beats. The spacing of the vibhaag accents makes them distinct, otherwise one avartan of Dhamar would be indistinguishable from two of Rupak or vice versa.[2] The first beat of any vibhaag is accompanied by a clap of the hands when reciting the taal and therefore is known as tali (or hand clap).

Furthermore, taals have a low point, known as khali (empty), which is always the first beat of a particular vibhaag, denoted in written form with '0' (zero). The khaal vibhaag has no beats on the bayan, i.e. no bass beats this can be seen as a way to enforce the balance between the usage of heavy (bass dominated) and fine (treble) beats or more simply it can be thought of another mnemonic to keep track of the rhythmic cycle (in addition to Sam). In recitation the Khaali vibhaag is indicated with a sideways wave of the dominant clapping hand (usually the right) or the placing of the back of the hand upon the base hand's palm in lieu of a clap making an "empty/nil" sound. The khali is played with a stressed syllable that can easily be picked out from the surrounding beats.

Hindustani Taals are typically played on tabla or pakhavaj. The specific strokes and the sound they produce are known as bols. Each bol has its own name that can be vocalized as well as written. Examples of bols may be heard in External Links below. The beats following the first beat of each vibhaag are indicated with digits that are greater than 0, 'X' representing the first beat - Sam, the '0' Khali (empty clap) and each number an individual consecutive beat). Rupak, almost uniquely, begins with the khali on Sam. Some rare taals even contain a "half-beat". For example, Dharami is an 11 1/2 beat cycle where the final "Ka" only occupies half the time of the other beats. Also note, this taal's 6th beat does not have a played syllable - in western terms it is a "rest".

Common Hindustani taals

Some taals, for example Dhamaar, Ek, Jhoomra and Chau talas, lend themselves better to slow and medium tempos. Others flourish at faster speeds, like Jhap or Rupak talas. Trital or Teental is one of the most popular, since it is as aesthetic at slower tempos as it is at faster speeds.

Various Gharanas (literally "Houses" which can be inferred to be "styles" - basically styles of the same art with cultivated traditional variances) also have their own preferences. For example, the Kirana Gharana uses Ektaal more frequently for Vilambit Khayal while the Jaipur Gharana uses Trital. Jaipur Gharana is also known to use Ada Trital, a variation of Trital for transitioning from Vilambit to Drut laey. There are many taals in Hindustani music, some of the more popular ones are:

| Name | Beats | Division | Vibhaga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tintal (or Trital or Teental) | 16 | 4+4+4+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Jhoomra | 14 | 3+4+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Tilwada | 16 | 4+4+4+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Dhamar | 14 | 5+2+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Ektal and Chautal | 12 | 2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 0 2 0 3 4 |

| Jhaptal and Jhampa | 10 | 2+3+2+3 | X 2 0 3 |

| Keherwa | 8 | 4+4 | |

| Roopak | 7 | 3+2+2 | X 2 3 |

| Dhadra | 6 | 3+3 | X 2 |

Additional Talas

Rarer Hindustani talas

| Name | Beats | Division | Vibhaga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adachoutal | 14 | 2+2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 2 0 3 0 4 0 |

| Brahmtal | 28 | 2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 0 2 3 0 4 5 6 0 7 8 9 10 0 |

| Dipchandi | 14 | 3+4+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Shikar | 17 | 6+6+2+3 | X 0 3 4 |

| Sultal | 10 | 2+2+2+2+2 | x 0 2 3 0 |

Rarer Carnatic talas

Other than these 35 talas there are 108 so-called anga talas. The following is the exhaustive pattern of beats used in constructing them.

| Anga | Symbol | Aksharakala | Mode of Counting |

| Anudrutam | U | 1 | 1beat |

| Druta | O | 2 | 1 beat + Visarijitam (wave of hand) |

| Druta-virama | (OU) | 3 | |

| Laghu (Chatusra-jati) | l | 4 | 1 beat + 3 finger count |

| Laghu-virama | U) | 5 | |

| Laghu-druta | O) | 6 | |

| Laghu-druta-virama | OU) | 7 | |

| Guru | 8 | 8 | A beat followed by circular movement of the right hand in the clockwise direction with closed fingers. |

| Guru-virama | (8U) | 9 | |

| Guru-druta | (8O) | 10 | |

| Guru-druta-virama | (8OU) | 11 | |

| Plutam | ) | 12 | 1 beat + kryshya (waving the right hand from right to left) + 1 sarpini (waving the right hand from left to right) - each of 4 aksharakalas OR a Guru followed by the hand waving downwards |

| Pluta-virana | U) | 13 | |

| Pluta-druta | O) | 14 | |

| Pluta-druta-virama | OU) | 15 | |

| Kakapadam | + | 16 | 1 beat + patakam (lifting the right hand) + kryshya + sarpini - each of 4 aksharakalas) |

Compositions are rare in these lengthy talas. They are mostly used in performing the Pallavi of Ragam Thanam Pallavis. Some examples of anga talas are:

Sarabhandana tala

| 8 | O | l | l | O | U | U) | |

| O | O | O | U | O) | OU) | U) | O |

| U | O | U | O | U) | O | (OU) | O) |

Simhanandana tala : It is the longest tala.

| 8 | 8 | l | ) | l | 8 | O | O |

| 8 | 8 | l | ) | l | ) | 8 | l |

| l | + |

Another type of tala is the chhanda tala. These are talas set to the lyrics of the Thirupugazh by the Tamil composer Arunagirinathar. He is said to have written 16000 hyms each in a different chhanda tala. Of these, only 1500-2000 are available.

References

(International) Literature

- Oxford Journals: A Study in East Indian Rhythm, Sargeant and Lahiri, Musical Quarterly.1931; XVII: 427-438

- Ancient Traditions—Future Possibilities: Rhythmic Training Through the Traditions of Africa, Bali and India, Author: Matthew Montfort, Mill Valley: Panoramic Press, 1985. ISBN 0-937879-00-2 (Spiral Bound Book)

- Humble, M (2002): The Development of Rhythmic Organization in Indian Classical Music, MA dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Manfred Junius: Die Tālas der nordindischen Musik (The Talas of North Indian Music), München (Munich), Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1983.

Kaufmann, Walter (1968), The Ragas of North India, Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Company.

External (Web) Links

- Colvin Russell: Tala Primer - A basic introduction to tabla and tala.

- KKSongs Talamala: Recordings of Tabla Bols, database for Hindustani Talas.

- Ancient Future: MIDI files of the common (major) Hindustani Talas.

- Instruments in Depth: Tabla: Drums of North India, an online feature from Bloomingdale School of Music (March, 2008)

- Chandra & David's Tabla site: The Cyclic Form in North Indian Tabla, Index of Tals (Tala) and others.

- San Diego State University: Rhythm - Indian Rhythm

- SICA Festival: Indian rhythm in Carnatic music... (The Hindu), 24 March 2006