Colonial history of the United States

beaner power

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The term colonial history of the United States refers to the history from the start of European settlement to the time of independence from Europe, and especially to the history of the thirteen colonies of Britain which declared themselves independent in 1776.[1] Starting in the late 16th century, England, Scotland, France, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands began to colonize eastern North America.[2][3] Many early attempts—notably the English Lost Colony of Roanoke—ended in failure, but several successful colonies were established. European settlers came from a variety of social and religious groups. No aristocrats settled permanently, but many adventurers, soldiers, farmers, and tradesmen arrived. The Dutch of New Netherland, the Swedes and Finns of New Sweden, the English, Irish and German Quakers of Pennsylvania, the English Puritans of New England, the English settlers of Jamestown, and the "worthy poor" of Georgia, among others—each group came to the new continent and built colonies with their distinctive social, religious, political and economic styles.[4]

Historians typically recognize four distinct regions in the lands that later became the Eastern United States. From north to south, they are: New England, the Middle Colonies, the Chesapeake Bay Colonies (Upper South) and the Lower South. Some historians add a fifth region, the frontier, which was never separately organized. Other colonies that contributed land to the future United States include New France, Quebec (Louisiana), New Spain, and Russian Alaska.

Goals of colonization

Colonizers came from European nation states with highly developed military, naval, governmental and entrepreneurial capabilities. The Spanish and Portuguese centuries-old experience of conquest and colonization during the Reconquista, coupled with new oceanic ship navigation skills, provided the tools, ability, and desire to colonize the New World. England, France and the Netherlands started colonies in both the West Indies and North America. They had the ability to build ocean-worthy ships, but did not have as strong a history of colonization in foreign lands as did Spain. However, the Tudors through early capitalism (mercantilism), gave their colonies in the Americas the characteristics of merchant-based investment that needed much less government control.[5][6]

Early colonial failures

Nova Scotia (New Scotland) was settled in 1629 and abandoned to the French in 1631.

Spain established several colonies in the area that is now the United States. Several of these early attempts failed. In 1526, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón founded the colony San Miguel de Guadalupe in present day Georgia or South Carolina. The colony only lasted a short while before disintegrating. It was also notable for perhaps being the first instance of African slave labor within the present boundaries of the United States. Pánfilo de Narváez attempted to start a colony in Florida in 1528. The Narváez expedition ended in disaster with only four members making it to Mexico in 1536. The Spanish Colony of Pensacola in West Florida (1559) was destroyed by a hurricane in 1561. Fort San Juan was established in 1567 in the interior of North Carolina but was destroyed by local Native Americans 18 months later. The Ajacan Mission, founded in 1570, failed the next year, very near the site of the later English colony of Jamestown, in the area that later became known as Virginia.[1]

The French established several colonies that failed, due to weather, disease or conflict with other European powers. A small group of French troops were left on Parris Island, South Carolina in 1562 to build Charlesfort, but left after a year when they were not resupplied from France. Fort Caroline established in present-day Jacksonville, Florida in 1564, lasted only a year before being destroyed by the Spanish from St. Augustine. In 1604, Saint Croix Island, Maine was the site of a short-lived French colony, much plagued by illness, perhaps scurvy.[1]

Spanish colonies

Florida

Spain established many small settlements in Florida. The most important, St. Augustine, Florida, founded in 1565, was repeatedly attacked and burned, but was the first permanent European settlement in what is now the continental United States. Pirate attacks were unrelenting against small outposts and even against St. Augustine. The British and their colonies repeatedly made war with Spain and its colonies and outposts. South Carolina launched large scale invasions in 1702 and 1704, which effectively destroyed the Spanish mission system. St. Augustine survived, but English-allied Indians such as the Yamasee conducted slave raids throughout Florida, killing or enslaving most of the region's natives.[1] In the mid-1700s, invading Seminoles from Georgia killed most of the remaining local Indians. Florida had about 3,000 Spaniards when Britain took control in 1763. Nearly all quickly left. Even though control was restored to Spain in 1783, Spain sent no more settlers or missionaries to Florida. The United States took possession in 1819.[7]

New Mexico (1598-1821)

Throughout the 16th century, Spain explored the southwest from Mexico with the most notable explorer being Francisco Coronado whose expedition rode throughout modern New Mexico, Arizona, southern Colorado, the panhandle of Oklahoma, and Kansas. However, no settlements were established by Coronado. The first colonization was under Don Juan de Oñate in 1598 where the first settlement in San Juan de Los Caballeros near Española, New Mexico and later Santa Fe, New Mexico around 1609. The second colonization came in 1692 under Diego de Vargas after the Pueblo Revolt. Even though there have been several claims within the boundaries of the Kingdom of New Mexico by several foreign powers (Texas, France, US), control had always been maintained by Spain (223 years) and later Mexico (25 years) until the arrival of the American Army of the West under Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny in 1846 during the Mexican-American War. Many direct descendants of the original colonists live on the land grants granted by Spain and later Mexico to this day.[1][8]

California (1769-1821)

Spanish explorers sailed along the coast of California from the early 16th century to the mid-18th century, but no settlements were established at that time.

Spain, starting in 1769, sent missionaries and soldiers who created a series of Catholic missions, accompanied by garrisons, towns, and ranches, along the southern and central coast of California. Father Junípero Serra, a Franciscan missionary, founded the mission chain, starting with San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. The California Missions comprised a series of 21 outposts established to spread Christianity among the local Native Americans, with the added benefit of confirming historic Spanish claims to the area. The missions introduced European technology, livestock and crops, while keeping the native people in peonage.[9]

The mission system (each mission was located about a day's ride apart, along the coast from San Diego to Sonoma) was supplemented by the establishment of "presidios", or garrison forts, and "pueblos", or civilian towns, under Spanish law. All were located near the coastline, and the resulting single traditional travel route between the missions, presidios, and pueblos became known as "El Camino Real" ("The Royal Road"), which became California's first highway.[10]

By 1820, Spanish influence was marked by the chain of missions reaching from San Diego to Sonoma (just north of San Francisco Bay), and extended inland approximately 25 to 50 miles (40 to 80 kilometres) from the missions. Outside of this zone, perhaps 200,000 to 250,000 Native Americans were continuing to lead traditional lives. The Spanish government (and after independence in 1821, the Mexican government) encouraged the settlement of California with large land grants that were turned into cattle and sheep ranches. The Hispanic population reached about 10,000 in the 1840s. The "El Camino Real" and missions later became a romantic symbol of an idyllic and peaceful past[citation needed]. The "Mission Revival Style" was an architectural movement that drew its inspiration from this idealized view of California's past.[10]

New Netherland

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

Nieuw-Nederland, or New Netherland, was the seventeenth century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands in what became New York State. The peak population was less than 10,000. The Dutch established a patroon system with feudal-like rights given to a few powerful landholders; they also established religious tolerance and free trade. The colony's capital, New Amsterdam, founded in 1625 and located at the southern tip of the island of Manhattan, would grow to become a major world city. The city was captured by the English in 1664; they took complete control of the colony in 1674. However the Dutch landholdings remained, and the Hudson River Valley maintained a traditionalistic Dutch character down to the 1820s.[11]

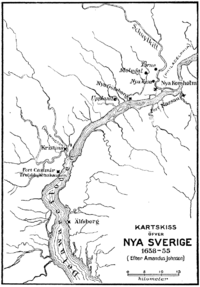

New Sweden

New Sweden (Template:Lang-sv) was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River Valley from 1638 to 1655. It was centered at Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, and included parts of the present-day states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Peter Minuit was the first governor of the newly established colony of New Sweden. Under Johan Björnsson Printz (governor from 1643 until 1653), the colony expanded from Fort Christina, establishing Fort Nya Elfsborg on the east bank of the Delaware River near present-day Salem, New Jersey and Fort Nya Gothenborg on Tinicum Island (to the immediate Southwest of today's Philadelphia). Peter Stuyvesant moved an army to the Delaware River in the late summer of 1655, leading to the immediate surrender of Fort Trinity and Fort Christina. New Sweden was incorporated into Dutch New Netherland on September 15, 1655.[1][12]

New France

New France was the area colonized by France from the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River, by Jacques Cartier in 1534. At its peak in 1712, the territory claimed by New France extended from Nova Scotia to Lake Superior and from the Hudson Bay to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. The territory was then divided into five colonies, each with its own administration: Canada, Acadia, Hudson Bay, Newfoundland and Louisiana. About 16,000 settlers came from France, and concentrated in villages along the St. Lawrence River and Acadia. There were few settlers elsewhere. Britain seized as spoils of war almost all the French areas east of the Mississippi by 1763. The area around New Orleans and west of the Mississippi passed to Spain, which ceded it to France in 1803, allowing France to sell it as the Louisiana Purchase to the United States.[1]

Russian colonies

The islands between Russia and Alaska and the adjacent coastal areas on both sides of the Bering Sea were peopled by the Aleut, Yupik, Chukchi and related tribes. The Russian tsars decided to explore the eastern extant of their empire (and determine whether a land bridge existed between Asia and the Americas). This led to the Second Kamchatka expedition in the 1730s and early 1740s. The first Russian colony in Alaska was founded in 1784 by Grigory Shelikhov.[13] The Russian-American Company was formed in 1799 with the influence of Nikolay Rezanov for the purpose of hunting sea otters for their fur. Subsequently, Russian explorers and settlers continued to establish trading posts in Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. Fort Ross in what is now Sonoma County, California was the southernmost Russian colony; it was abandoned in 1841.[14]

In 1867 the U.S. purchased Alaska. Russian missionaries such as Herman of Alaska established the Orthodox Church among the native tribes. The Orthodox Church and Alaska Natives continue to be closely associated.

British colonies

England made its first successful efforts at the start of the 17th century for several reasons. During this era, English proto-nationalism and national assertiveness blossomed under the threat of Spanish invasion, assisted by a degree of Protestant militarism and the energy of Queen Elizabeth. At this time, however, there was no official attempt by the English government to create a colonial empire. Rather, the motivation behind the founding of colonies was piecemeal and variable. Practical considerations, such as commercial enterprise, over-population and the desire for freedom of religion, played their parts. The main waves of settlement came in the 17th century. After 1700 most immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants.[15] Between the late 1610s and the American Revolution, the British shipped an estimated 50,000 convicts to its American colonies.[16] The first convicts to arrive pre-dated the arrival of the Mayflower.

Chesapeake Bay area

Virginia

The first successful English colony was Jamestown, established in 1607, on a small river near Chesapeake Bay. The venture was financed and coordinated by the London Virginia Company, a joint stock company looking for gold. Its first years were extremely difficult, with very high death rates from disease and starvation, wars with local Indians, and little gold. The colony survived and flourished by turning to tobacco as a cash crop. By the late 17th century, Virginia's export economy was largely based on tobacco, and new, richer settlers came in to take up large portions of land, build large plantations and import indentured servants and slaves. In 1676, Bacon's Rebellion occurred, but was suppressed by royal officials. After Bacon's Rebellion, African slaves rapidly replaced indentured servants as Virginia's main labor force.[17][18]

The colonial assembly shared power with a royally appointed governor. On a more local level, governmental power was invested in county courts, which were self-perpetuating (the incumbents filled any vacanacies and there never were popular elections.) As cash crop producers, Chesapeake plantations were heavily dependent on trade with England. With easy navigation by river, there were few towns and no cities; planters shipped directly to Britain. High death rates and a very young population profile characterized the colony during its first years.[18]

New England

Pilgrims (Separatists)

The Pilgrims were a small Protestant sect based in England and the Netherlands. One group sailed on the Mayflower and settled in Massachusetts. After drawing up the Mayflower Compact by which they gave themselves broad powers of self-governance, they established the small Plymouth Colony in 1620; Plymouth later merged with the Massachusetts Bay colony. William Bradford was their main leader. The Connecticut Colony was an English colony that became the state of Connecticut.[19] Originally known as the River Colony, the colony was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritans. Providence Plantation was founded in 1636 by Rev. Roger Williams on land provided by the Narragansett sachem Canonicus. Williams, fleeing from religious persecution in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, agreed with his fellow settlers on an egalitarian constitution providing for majority rule "in civil things" and "liberty of conscience".[17]

Puritans

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new, pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived; many died soon after arrival, but the others found a healthy climate and an ample food supply. See Migration to New England (1620–1640)

The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit, and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States.[neutrality is disputed] They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation". They fled England and in America attempted to create a "nation of saints" or a "City upon a Hill": an intensely religious, thoroughly righteous community designed to be an example for all of Europe. Roger Williams, who preached religious toleration, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other refugees from the Puritan community, such as Anne Hutchinson.[17]

Economically, Puritan New England fulfilled the expectations of its founders. Unlike the cash crop-oriented plantations of the Chesapeake region, the Puritan economy was based on the efforts of self-supporting farmsteads who traded only for goods they could not produce themselves.[citation needed] There was a generally higher economic standing and standard of living in New England than in the Chesapeake.[citation needed] Along with agriculture, fishing, and logging, New England became an important mercantile and shipbuilding center, serving as the hub for trading between the southern colonies and Europe.[20]

Middle Colonies

The Middle Colonies, consisting of the present-day states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, were characterized by a large degree of diversity—religious, political, economic, and ethnic. The Dutch colony of New Netherland was taken over by the British and renamed New York but large numbers of Dutch remained in the colony. Many German and Irish immigrants settled in these areas, as well as in Connecticut. A large portion of the settlers who came to Pennsylvania were German.[20] Philadelphia became the center of the colonies. By the end of the colonial period 30,000 people lived there from many diverse nations and trades.

Lower South

The colonial South included the plantation colonies of the Chesapeake region (Virginia, Maryland, and, by some classifications, Delaware) and the lower South (Carolina, which eventually split into North and South Carolina, and Georgia).[20]

Carolinas

The first attempted English settlement south of Virginia was the Province of Carolina. It was a private venture, financed by a group of English Lords Proprietors, who obtained a Royal Charter to the Carolinas in 1663, hoping that a new colony in the south would become profitable like Jamestown. Carolina was not settled until 1670, and even then the first attempt failed because there was no incentive for emigration to the south. However, eventually the Lords combined their remaining capital and financed a settlement mission to the area led by John West[disambiguation needed]. The expedition located fertile and defensible ground at what was to become Charleston (originally Charles Town for Charles II of England), thus beginning the English colonization of the mainland. The original settlers in South Carolina established a lucrative trade in provisions, deerskins and Indian captives with the Caribbean islands. They came mainly from the English colony of Barbados and brought African slaves with them. Barbados, as a wealthy sugarcane plantation island, was one of the early English colonies to use large numbers of Africans in plantation style agriculture. The cultivation of rice was introduced during the 1690s via Africans from the rice-growing regions of West Africa. North Carolina remained a frontier through the early colonial period.[20]

At first, South Carolina was politically divided. Its ethnic makeup included the original settlers, a group of rich, slave-owning English settlers from the island of Barbados; and Huguenots, a French-speaking community of Protestants. Nearly continuous frontier warfare during the era of King William's War and Queen Anne's War drove economic and political wedges between merchants and planters. The disaster of the Yamasee War, in 1715, set off a decade of political turmoil. By 1729, the proprietary government had collapsed, and the Proprietors sold both colonies back to the British crown.[20]

Georgia

James Oglethorpe, an 18th century British Member of Parliament, established Georgia Colony as a common solution to two problems. At that time, tension between Spain and Great Britain was high, and the British feared that Spanish Florida was threatening the British Carolinas. Oglethorpe decided to establish a colony in the contested border region of Georgia and populate it with debtors who would otherwise have been imprisoned according to standard British practice. This plan would both rid Great Britain of its undesirable elements and provide her with a base from which to attack Florida. The first colonists arrived in 1733.[20]

Georgia was established on strict moralistic principles. Slavery was forbidden, as was alcohol and other forms of supposed immorality. However, the reality of the colony was far from ideal. The colonists were unhappy about the puritanical lifestyle and complained that their colony could not compete economically with the Carolina rice plantations. Georgia initially failed to prosper, but eventually the restrictions were lifted, slavery was allowed, and it became as prosperous as the Carolinas. The colony of Georgia never had a specific religion. It consisted of people of varied faiths.

East and West Florida

In 1763, Great Britain received East and West Florida from the Spanish. The Floridas remained loyal to Great Britain during the American Revolution. They were returned to Spain in 1783 (in exchange for Havana), at which time most Englishmen left. The Spanish then neglected the Floridas: few Spaniards lived there when the US bought the area in 1819.[1]

British colonial government in 1776

The three forms of colonial government in 1776 were provincial, proprietary, and charter.[21] Under the feudal system of Great Britain (earlier, of England), these were all subordinate to the monarch, with no explicit relationship with the British Parliament.

Provincial colonies

New Hampshire, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were provincial colonies.

The provincial government was governed by commissions created at pleasure by the monarch. A governor and council were appointed, invested with general executive powers, and authorized to call an assembly consisting of two houses (the council itself was the upper house, the assembly being the lower house), made up of representatives of the freeholders and planters of the province. The governor had the power of absolute veto, and could prorogue (i.e., delay) and dissolve the assembly.

The assembly could make all local laws and ordinances that were not inconsistent with the laws of England.

Proprietary colonies

Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland were proprietary colonies.

Proprietary governments were grants by patents for special territory to one or more persons from the monarch, giving them rights as proprietors of the land and with general powers of government, in the nature of a feudal principality or royal dependency, and subject to the control of the monarch.

The proprietaries appointed the governor and the legislature was organized and called at his (or their) pleasure. Executive authority was held by the proprietary or his governor.

Charter colonies

Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Providence Plantation, and Connecticut were charter colonies.

Charter governments were political corporations created by letters patent, giving the grantees control of the land and the powers of legislative government. The charters provided a fundamental constitution and divided powers among legislative, executive, and judicial functions, with those powers being vested in officials.

Unification of the British colonies

A common defense

One event that reminded colonists of their shared identity as British subjects was the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) in Europe. This conflict spilled over into the colonies, where it was known as "King George's War". The major battles took place in Europe, but American colonial troops fought the French and their Indian allies in New York and New England.

At the Albany Congress of 1754, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the colonies be united by a Grand Council overseeing a common policy for defense, expansion, and Indian affairs. While the plan was thwarted by colonial legislatures and King George II, it was an early indication that the British colonies of North America were headed towards unification.[22]

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was the American extension of the general European conflict known as the Seven Years' War. While previous colonial wars in North America had started in Europe and then spread to the colonies, the French and Indian War is notable for having started in North America and then spreading to Europe. Increasing competition between Britain and France, especially in the Great Lakes and Ohio valley, was one of the primary origins of the war.[23]

The French and Indian War took on a new significance for the North American colonists in Great Britain when William Pitt the elder decided that it was necessary to win the war against France at all costs. For the first time, North America was one of the main theaters of what could be termed a "world war". During the war, the British Colonies' (including the thirteen colonies' that would later become the basis of the United States) position as part of the British Empire was made truly apparent, as British military and civilian officials took on an increased presence in the lives of Americans. The war also increased a sense of American unity in other ways. It caused men, who might normally have never left their own colony, to travel across the continent, fighting alongside men from decidedly different, yet still "American", backgrounds. Throughout the course of the war, British officers trained American ones (most notably George Washington) for battle—which would later benefit the American Revolution. Also, colonial legislatures and officials had to cooperate intensively, for the first time, in pursuit of the continent-wide military effort.[23]

In the Treaty of Paris (1763), France surrendered its vast North American empire to Britain. Before the war, Britain held the thirteen American colonies, most of present-day Nova Scotia, and most of the Hudson Bay watershed. Following the war, Britain gained all French territory east of the Mississippi River, including Quebec, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio valley. Britain also gained the Spanish colonies of East and West Florida. In removing a major foreign threat to the thirteen colonies, the war also largely removed the colonists' need of colonial protection.

The British and colonists triumphed jointly over a common foe. The colonists' loyalty to the mother country was stronger than ever before. However, disunity was beginning to form. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder had decided to wage the war in the colonies with the use of troops from the colonies and tax funds from Britain itself. This was a successful wartime strategy, but after the war was over, each side believed that it had borne a greater burden than the other. The British elite, the most heavily taxed of any in Europe, pointed out angrily that the colonists paid little to the royal coffers. The colonists replied that their sons had fought and died in a war that served European interests more than their own. This dispute was a link in the chain of events that soon brought about the American Revolution.[23]

Ties to the British Empire

Although the colonies were very different from one another, they were still a part of the British Empire in more than just name.

Socially, the colonial elite of Boston, New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia saw their identity as British. Although many had never been to Britain, they imitated British styles of dress, dance, and etiquette. This social upper echelon built its mansions in the Georgian style, copied the furniture designs of Thomas Chippendale, and participated in the intellectual currents of Europe, such as Enlightenment. To many of their inhabitants, the seaport cities of colonial America were truly British cities.[24]

Many of the political structures of the colonies drew upon the republicanism expressed by opposition leaders in Britain, most notably the Commonwealth men and the Whig traditions. Many Americans at the time saw the colonies' systems of governance as modeled after the British constitution of the time, with the king corresponding to the governor, the House of Commons to the colonial assembly, and the House of Lords to the Governor's council. The codes of law of the colonies were often drawn directly from English law; indeed, English common law survives not only in Canada, but also throughout the United States. Eventually, it was a dispute over the meaning of some of these political ideals, especially political representation, and republicanism that led to the American Revolution.[25]

Another point on which the colonies found themselves more similar than different was the booming import of British goods. The British economy had begun to grow rapidly at the end of the 17th century, and by the mid-18th century, small factories in Britain were producing much more than the nation could consume. Finding a market for their goods in the British colonies of North America, Britain increased her exports to that region by 360% between 1740 and 1770. Because British merchants offered generous credit to their customers,[citation needed] Americans began buying staggering amounts of British goods. From Nova Scotia to Georgia, all British subjects bought similar products, creating and anglicizing a sort of common identity.[24]

From unity to revolution

Royal Proclamation

The general sentiment of inequity that arose soon after the Treaty of Paris was solidified by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which temporarily prohibited settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists resented the measure, and it was never enforced.

Acts of Parliament

Parliament had generally been preoccupied with affairs in Europe and let the colonies govern themselves. It was no longer willing to do so. A series of measures resulting from this policy change, while affecting the New England colonies most directly, would continue to arouse opposition in the 'thirteen colonies' over the next thirteen years:

- Currency Act (1764)

- Sugar Act (1764)

- Stamp Act 1765

- First Quartering Act (1765)

- Declaratory Act (1766)

- Townshend Revenue Act (1767)

- Tea Act (1773)

- The Intolerable Acts, also called the Coercive or Punitive Acts

- Second Quartering Act (1774)

- Quebec Act (1774)

- Massachusetts Government Act (1774)

- Administration of Justice Act (1774)

- Boston Port Act (1774)

- Prohibitory Act (1775)

Colonial life

New England

In New England, the Puritans created self-governing communities of religious congregations of farmers, or yeomen, and their families. High-level politicians gave out plots of land to male settlers, or proprietors, who then divided the land amongst themselves. Large portions were usually given to men of higher social standing, but every white man had enough land to support a family. Also important was the fact that every white man had a voice in the town meeting. The town meeting levied taxes, built roads, and elected officials to manage town affairs.

The Congregational Church, the church the Puritans founded, was not automatically joined by all New England residents because of Puritan beliefs that God singled out only a few specific people for salvation. Instead, membership was limited to those who could convincingly "test" before members of the church that they had been saved. They were known as "the elect" or "Saints" and made up less than 40% of the population of New England.

Farm life

A majority of New England residents were small farmers. Within these small farm families, and English families as well, a man had complete power over the property and his wife. When married, an English woman lost her maiden name and personal identity, meaning she could not own property, file lawsuits, or participate in political life, even when widowed. The role of wives was to raise and nurture healthy children and support their husbands. Most women carried out these duties. In the mid-18th century, women usually married in their early 20s and had 6 to 8 children, most of whom survived to adulthood. Farm women provided most of the materials needed by the rest of the family by spinning yarn from wool and knitting sweaters and stockings, making candles and soap, and churning milk into butter.

Most New England parents tried to help their sons establish farms of their own. When sons married, fathers gave them gifts of land, livestock, or farming equipment; daughters received household goods, farm animals, and/or cash. Arranged marriages were very unusual; normally, children chose their own spouses from within a circle of suitable acquaintances who shared their religion and social standing. Parents retained veto power over their children's marriages.

New England farming families generally lived in wooden houses because of the abundance of trees. A typical New England farmhouse was one-and-a-half stories tall and had a strong frame (usually made of large square timbers) that was covered by wooden clapboard siding. A large chimney stood in the middle of the house that provided cooking facilities and warmth during the winter. One side of the ground floor contained a hall, a general-purpose room where the family worked and ate meals. Adjacent to the hall was the parlor, a room used to entertain guests that contained the family's best furnishings and the parent's bed. Children slept in a loft above, while the kitchen was either part of the hall or was located in a shed along the back of the house. Because colonial families were large, these small dwellings had much activity and there was little privacy.

By the middle of the 18th century, this way of life was facing a crisis as the region's population had nearly doubled each generation—from 100,000 in 1700 to 200,000 in 1725, to 350,000 by 1750—because farm households had many children, and most people lived until they were 60 years old. As colonists in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island continued to subdivide their land between farmers, the farms became too small to support single families. This overpopulation threatened the New England ideal of a society of independent yeoman farmers.

Some farmers obtained land grants to create farms in undeveloped land in Massachusetts and Connecticut or bought plots of land from speculators in New Hampshire and what later became Vermont. Other farmers became agricultural innovators. They planted nutritious English grass such as red clover and timothy-grass, which provided more feed for livestock, and potatoes, which provided a high production rate that was an advantage for small farms. Families increased their productivity by exchanging goods and labor with each other. They loaned livestock and grazing land to one another and worked together to spin yarn, sew quilts, and shuck corn. Migration, agricultural innovation, and economic cooperation were creative measures that preserved New England's yeoman society until the 19th century.

Town life

By the mid eighteenth century in New England, shipbuilding was a staple. The British crown often turned to the cheap, yet strongly built American ships. There was a shipyard at the mouth of almost every river in New England.

By 1750, a variety of artisans, shopkeepers, and merchants provided services to the growing farming population. Blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and furniture makers set up shops in rural villages. There they built and repaired goods needed by farm families. Stores selling English manufactures such as cloth, iron utensils, and window glass as well as West Indian products like sugar and molasses were set up by traders. The storekeepers of these shops sold their imported goods in exchange for crops and other local products including roof shingles, potash, and barrel staves. These local goods were shipped to towns and cities all along the Atlantic Coast. Enterprising men set up stables and taverns along wagon roads to service this transportation system.

After these products had been delivered to port towns such as Boston and Salem in Massachusetts, New Haven in Connecticut, and Newport and Providence in Rhode Island, merchants then exported them to the West Indies where they were traded for molasses, sugar, gold coins, and bills of exchange (credit slips). They carried the West Indian products to New England factories where the raw sugar was turned into granulated and sugar and the molasses distilled into rum. The gold and credit slips were sent to England where they were exchanged for manufactures, which were shipped back to the colonies and sold along with the sugar and rum to farmers.

Other New England merchants took advantage of the rich fishing areas along the Atlantic Coast and financed a large fishing fleet, transporting its catch of mackerel and cod to the West Indies and Europe. Some merchants exploited the vast amounts of timber along the coasts and rivers of northern New England. They funded sawmills that supplied cheap wood for houses and shipbuilding. Hundreds of New England shipwrights built oceangoing ships, which they sold to British and American merchants.

Many merchants became very wealthy by providing their goods to the agricultural population and ended up dominating the society of sea port cities. Unlike yeoman farmhouses, these merchants resembled the lifestyle of that of the upper class of England living in elegant two-and-a-half story houses designed the new Georgian style. These Georgian houses had a symmetrical façade with equal numbers of windows on both sides of the central door. The interior consisted of a passageway down the middle of the house with specialized rooms such as a library, dining room, formal parlour, and master bedroom off the sides. Unlike the multi-purpose halls and parlours of the yeoman houses, each of these rooms served a separate purpose. In a Georgian house, men mainly used certain rooms, such as the library, while women mostly used the kitchen. These houses contained bedrooms on the second floor that provided privacy to parents and children.

Culture and education

Elementary education was widespread in New England. Early Puritan settlers believed it was necessary to study the Bible, so children were taught to read at an early age. It was also required that each town pay for a primary school. About 10 percent enjoyed secondary schooling and funded grammar schools in larger towns. Most boys learned skills from their fathers on the farm or as apprentices to artisans. Few girls attended formal schools, but most were able to get some education at home or at so-called "Dame schools" where women taught basic reading and writing skills in their own houses. By 1750, nearly 90% of New England's women and almost all of its men could read and write. Puritans founded Harvard College in 1636 and Yale College in 1701. Later, Baptists founded Rhode Island College (now Brown University) in 1764 and Congregationalists established Dartmouth College in 1769. Virginia founded schools the College of William and Mary in 1693. The colleges appealed primarily to aspiring ministers, lawyers or doctors. There were no separate seminaries, law schools or divinity schools.

New Englanders wrote journals, pamphlets, books and especially sermons--more than all of the other colonies combined. Cotton Mather, a Boston minister published Magnalia Christi Americana (The Great Works of Christ in America, 1702), while revivalist Jonathan Edwards wrote his philosophical work, A Careful and Strict Enquiry Into...Notions of...Freedom of Will... (1754). Most music had a religious theme as well and was mainly the singing of Psalms. Because of New England's deep religious beliefs, artistic works that were insufficiently religious or too "worldly" were banned, especially the theater.

Religion

Some migrants who came to Colonial America were in search of religious freedom. London did not make the Church of England official in the colonies--it never sent a bishop--so religious practice became diverse.[26]

The Great Awakening was a major religious revival movement that took place in most colonies in the 1730s and 1740s.[27] The movement began with Jonathan Edwards, a Massachusetts preacher who sought to return to the Pilgrims' strict Calvinist roots and to reawaken the "Fear of God." English preacher George Whitefield and other itinerant preachers continued the movement, traveling across the colonies and preaching in a dramatic and emotional style. Followers of Edwards and other preachers of similar religiosity called themselves the "New Lights", as contrasted with the "Old Lights", who disapproved of their movement. To promote their viewpoints, the two sides established academies and colleges, including Princeton and Williams College. The Great Awakening has been called the first truly American event.[28]

A similar pietistic revival movement took place among some of German and Dutch settlers, leading to more divisions. By the 1770s, the Baptists were growing rapidly both in the north (where they founded Brown University), and in the South (where they challenged the previously unquestioned moral authority of the Anglican establishment).

Mid-Atlantic Region

Unlike New England, the Mid-Atlantic Region gained much of its population from new immigration, and by 1750, the combined populations of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had reached nearly 300,000 people. By 1750, about 60,000 Irish and 50,000 Germans came to live in British North America, many of them settling in the Mid-Atlantic Region. William Penn, the man who founded the colony of Pennsylvania in 1682, attracted an influx of immigrants with his policies of religious liberty and freehold ownership. "Freehold" meant that farmers owned their land free and clear of leases. The first major influx of immigrants came mainly from Ireland. Many Germans came to escape the religious conflicts and declining economic opportunities in Germany and Switzerland.

Ways of life

Much of the architecture of the Middle Colonies reflects the diversity of its peoples. In Albany and New York City, a majority of the buildings were Dutch style with brick exteriors and high gables at each end while many Dutch churches were shaped liked an octagon. Using cut stone to build their houses, German and Welsh settlers in Pennsylvania followed the way of their homeland and completely ignored the plethora of timber in the area. An example of this would be Germantown, Pennsylvania where 80 percent of the buildings in the town were made entirely of stone. On the other hand, settlers from Ireland took advantage of America's ample supply of timber and constructed sturdy log cabins.

Ethnic cultures also affected the styles of furniture. Rural Quakers preferred simple designs in furnishings such as tables, chairs, chests and shunned elaborate decorations. However, some urban Quakers had much more elaborate furniture. The city of Philadelphia became a major center of furniture-making because of its massive wealth from Quaker and British merchants. Philadelphian cabinet makers built elegant desks and highboys. German artisans created intricate carved designs on their chests and other furniture with painted scenes of flowers and birds. German potters also crafted a large array of jugs, pots, and plates, of both elegant and traditional design.

There were ethnic differences in the treatment of women. Among Puritan settlers in New England, wives almost never worked in the fields with their husbands. In German communities in Pennsylvania, however, many women worked in fields and stables. German and Dutch immigrants granted women more control over property, which was not permitted in the local English law. Unlike English colonial wives, German and Dutch wives owned their own clothes and other items and were also given the ability to write wills disposing of the property brought into the marriage.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, approximately 85 percent of white Americans were of English, Irish, Welsh, or Scottish descent. Approximately 8.8 percent of whites were of German ancestry, and 3.5 per cent were of Dutch origin.

Farming

Ethnicity made a difference in agricultural practice. As an example, German farmers generally preferred oxen rather than horses to pull their plows and Scots-Irish made a farming economy based on hogs and corn. In Ireland, people farmed intensively, working small pieces of land trying to get the largest possible production-rate from their crops. In the American colonies, settlers from northern Ireland focused on mixed-farming. Using this technique, they grew corn for human consumption and as feed for hogs and other livestock. Many improvement-minded farmers of all different backgrounds began using new agricultural practices to raise their output. During the 1750s, these agricultural innovators replaced the hand sickles and scythes used to harvest hay, wheat, and barley with the cradle scythe, a tool with wooden fingers that arranged the stalks of grain for easy collection. This tool was able to triple the amount of work down by farmers in one day. Farmers also began fertilizing their fields with dung and lime and rotating their crops to keep the soil fertile.

Before 1720, most colonists in the mid-Atlantic region worked with small-scale farming and paid for imported manufactures by supplying the West Indies with corn and flour. In New York, a fur-pelt export trade to Europe flourished adding additional wealth to the region. After 1720, mid-Atlantic farming stimulated with the international demand for wheat. A massive population explosion in Europe brought wheat prices up. By 1770, a bushel of wheat cost twice as much as it did in 1720. Farmers also expanded their production of flaxseed and corn since flax was a high demand in the Irish linen industry and a demand for corn existed in the West Indies.

Some immigrants who just arrived purchased farms and shared in this export wealth, but many poor German and Irish immigrants were forced to work as agricultural wage laborers. Merchants and artisans also hired these homeless workers for a domestic system for the manufacture of cloth and other goods. Merchants often bought wool and flax from farmers and employed newly-arrived immigrants, who had been textile workers in Ireland and Germany, to work in their homes spinning the materials into yarn and cloth. Large farmers and merchants became wealthy, while farmers with smaller farms and artisans only made enough for subsistence. The Mid-Atlantic region, by 1750, was divided by both ethnic background and wealth.

Seaports

Seaports, which expanded from wheat trade, had more social classes than anywhere else in the Middle Colonies. By 1750, the population of Philadelphia had reached 25,000, New York 15,000, and the port of Baltimore 7,000. Merchants dominated seaport society and about 40 merchants controlled half of Philadelphia's trade. Wealthy merchants in Philadelphia and New York, like their counterparts in New England, built elegant Georgian-style mansions.

Shopkeepers, artisans, shipwrights, butchers, coopers, seamstresses, cobblers, bakers, carpenters, masons, and many other specialized professions, made up the middle class of seaport society. Wives and husbands often worked as a team and taught their children their crafts to pass it on through the family. Many of these artisans and traders made enough money to create a modest life.

Laborers stood at the bottom of seaport society. These poor people worked on the docks unloading inbound vessels and loading outbound vessels with wheat, corn, and flaxseed. Many of these were African American; some were free while others were enslaved. In 1750, blacks made up about 10 percent of the population of New York and Philadelphia. Hundreds of seamen, some who were African American, worked as sailors on merchant ships.

Southern Colonies

The Southern Colonies were mainly dominated by the wealthy slave-owning planters in Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina. These planters owned massive estates that were worked by African slaves. Of the 650,000 inhabitants of the South in 1750, about 250,000 or 40 percent, were slaves. Planters used their wealth to dominate the local tenants and yeoman farmers. At election time, they gave these farmers gifts of rum and promised to lower taxes to take control of colonial legislatures.

Plantations

Beginning in the 1720s, after many years of hard life and starvation, the next generation of planters began to construct large Georgian-style mansions, and hunt deer from horseback. Wealthy women in the Southern colonies shared in the British culture. They read British magazines, wore fashionable clothing of British design, and served an elaborate afternoon tea. These efforts were the most successful in South Carolina, where wealthy rice planters lived in townhouses in Charleston, a busy port city. Active social seasons also existed in towns, such as Annapolis, Maryland, and on tobacco plantations along the James River in Virginia.

Slaves

The African slaves who worked on the indigo, tobacco, and rice fields in the South came from western and central Africa. Slavery in Colonial America was very oppressive as it passed on from generation to generation, and slaves had no legal rights. The colonies that had the most specialization in production of goods, such as sugar and coffee, relied most on slaves and consequentially, had the highest per capita (including slaves) income in the New World. However, the slaves were very poor and received just enough to live. Between 1500 and 1700, over 60% of the 6 million people who traveled to the New World, were involuntary slaves.<Sokoloff and Engerman><History Lessons> In 1700, there were about 9,600 slaves in the Chesapeake region and a few hundred in the Carolinas. About 170,000 more Africans arrived over the next five decades. By 1750, there were more than 250,000 slaves in British America; and, in the Carolinas, they made up about 60 percent of the total population. The first post-colonial Census found 697,681 slaves and 59,527 free blacks, who together made up about 20% of the country's population. Most slaves in South Carolina were born in Africa, while half the slaves in Virginia and Maryland were born in the colonies.[citation needed]

See also

External Links

Bibliography

References

- Ciment, James, ed. Colonial America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History (2005)

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest, ed. Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies (3 vol 1993)

- Cooke, Jacob, ed. North America in Colonial Times: An Encyclopedia for Students (1998)

- Gallay, Alan, ed. Colonial Wars of North America, 1512-1763: An Encyclopedia (1996) excerpt and text search

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes) (1936–1970), Pulitzer Prize; highly detailed discussion of every British colony in the New World

- Vickers, Daniel, ed. A Companion to Colonial America (2006)

Secondary sources

- Adams, James Truslow (1921). The Founding of New England. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Andrews, Charles M. (1914). "Colonial Commerce". American Historical Review. 20 (1). American Historical Association: 43–63. doi:10.2307/1836116. JSTOR 10.2307/1836116.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Also online at JSTOR - Andrews, Charles M. (1904). Colonial Self-Government, 1652-1689. online

- Andrews, Charles M. (1934–38). The Colonial Period of American History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) (the standard overview in four volumes) - Beeman, Richard R. "The Varieties of Political Experience in Eighteenth-Century America (2006) excerpt and text search

- Beer, George Louis. "British Colonial Policy, 1754-1765," Political Science Quarterly, vol 22 (March 1907) pp 1–48; online edition

- Berkin, Carol. First Generations: Women in Colonial America (1997) 276pp excerpt and text search

- Bonomi, Patricia U. (1988). Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America. (online at ACLS History e-book project)

- Bonomi, Patricia U. (1971). A Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York.

- Breen, T. H (1980). Puritans and Adventurers: Change and Persistence in Early America.

- Brown, Kathleen M. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (1996) 512pp excerpt and text search

- Bruce, Philip A. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century: An Inquiry into the Material Condition of the People, Based on Original and Contemporaneous Records. (1896), very old fashioned history online edition

- Carr, Lois Green and Philip D. Morgan. Colonial Chesapeake Society (1991), 524pp excerpt and text search

- Conforti, Joseph A. Saints and Strangers: New England in British North America (2006). 236pp; the latest scholarly history of New England

- Crane, Verner W. (1920). The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732.

- Crane, Verner W. (1919). "The Southern Frontier in Queen Anne's War". American Historical Review. 24 (3). American Historical Association: 379–95. doi:10.2307/1835775. JSTOR 10.2307/1835775.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) in JSTOR - Fischer, David Hackett. Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1989), comprehensive look at major ethnic groups excerpt and text search

- Greene, Evarts Boutelle. Provincial America, 1690-1740 (1905) online edition. old, comprehensive overview by scholar

- Hatfield, April Lee. Atlantic Virginia: Intercolonial Relations in the Seventeenth Century (2007) excerpt and text search

- Illick, Joseph E. Colonial Pennsylvania: A History, (1976) online edition

- Kammen, Michael. Colonial New York: A History, (2003)

- Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (2009)

- Kulikoff, Allan (2000). From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers.

- Labaree, Benjamin Woods. Colonial Massachusetts: A History, (1979)

- Middleton, Richard. Colonial America: A History, 1565-1776 (3rd ed 2002), 576pp excerpt and text search

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975) Pulitzer Prize online edition

- Tate, Thad W. Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century (1980) excerpt and text search

- Taylor, Alan. American Colonies, (2001) survey by leading scholar excerpt and text search

- Wood, Betty. Slavery in Colonial America, 1619-1776 (2005)

Primary sources

- Kavenagh, W. Keith, ed. Foundations of Colonial America: A Documentary History (1973) 4 vol.

- Brett Rushforth, Brett, Paul Mapp, and Alan Taylor, eds. North America and the Atlantic World: A History in Documents (2008)

Online sources

- Classics of American Colonial History complete text of older scholarly articles

- Archiving Early America

- Colonial History of the United States at Thayer's American History site

- Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cooke, ed. North America in Colonial Times (1998)

- ^ http://www.dalhousielodge.org/Thesis/scotstonc.htm

- ^ Colonial North America

- ^ Colonial America 1600-1775

- ^ Richard Middleton, Colonial America: A History, 1565-1776 3rd ed. 2002.

- ^ Wallace Notestein, English People on Eve of Colonization, 1603-30 (1954)

- ^ Michael Gannon, The New History of Florida (1996)

- ^ David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (2009)

- ^ David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (2009)

- ^ a b Andrew F. Rolle, California: A History, 2008.

- ^ Michael G. Kammen, Colonial New York: A History (1996)

- ^ Johnson, Amandus The Swedes on the Delaware (1927)

- ^ Meeting of Frontiers: Alaska - The Russian Colonization of Alaska

- ^ Russian Settlement at Fort Ross, California, in the 19th century

- ^ Indentured Servitude in Colonial America, Deanna Barker, Frontier Resources

- ^ Butler, James Davie (1896). "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies". American Historical Review 2. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Alan Taylor, American Colonies,, 2001.

- ^ a b Ronald L. Heinemann, Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607-2007, 2008.

- ^ Prior to 1664 it was claimed by the Dutch as part of New Netherland, with a 1623 settlement at Hartford, called Fort Goede Hoop, which pre-dates any English settlement in the state.

- ^ a b c d e f James Ciment, ed. Colonial America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History, 2005.

- ^ Donaldson, Thomas, ed. (1881). The Public Domain. Washington: House of Representatives. pp. 465–466.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ H. W. Brands, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2002)

- ^ a b c Fred Anderson, The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War (2006)

- ^ a b Daniel Vickers, ed. A Companion to Colonial America (2006), ch 13-16

- ^ Bailyn, Bernard, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967); Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2003)

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (2nd ed. 2004) ch 17-22

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (2nd ed. 2004) ch 18, 20

- ^ Historian Jon Butler has questioned the concept of a Great Awakening, but most historians use it. John M. Murrin (1983). "No Awakening, No Revolution? More Counterfactual Speculations". Reviews in American History. 11 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 161–171. doi:10.2307/2702135. JSTOR 10.2307/2702135.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)