Messiah (Handel)

Template:Handel oratorios Messiah (HWV 56) is an English oratorio composed by George Frideric Handel, and is one of the most popular works in the Western choral literature. The libretto by Charles Jennens is drawn entirely from the King James and Great Bibles, and interprets the Christian doctrine of the Messiah. Messiah, often incorrectly called The Messiah, is one of Handel's most famous works.

Composed in London during the summer of 1741 and premiered in Dublin, Ireland on 13 April 1742, it was repeatedly revised by Handel, reaching its most familiar version in the performance to benefit the Foundling Hospital in 1754. In 1789 Mozart orchestrated a German version of the work; his added woodwind parts, and the edition by Ebenezer Prout, were commonly heard until the mid-20th century and the rise of historically informed performance.

The Messiah sing-alongs now common at Christmas often consist of only the first of the oratorio's three parts, with the Hallelujah Chorus (originally concluding the second part) replacing His Yoke is Easy in the first part.

Overview

Messiah presents an interpretation of the Christian view of the Messiah, or "the anointed one" as Jesus the Christ. Divided into three parts, the libretto covers the prophecies concerning the Christ, the birth, miracles, crucifixion, resurrection and ascension of Jesus, and finally the End Times with the Christ's final victory over death and sin.

Although the work was conceived for secular theatre and first performed during Lent, it has become common practice since Handel's death to perform Messiah during Advent, the preparatory period of the Christmas season, rather than in Lent or at Easter. Messiah is often performed in churches as well as in concert halls. Christmas concerts often feature only the first section of Messiah plus the "Hallelujah" chorus, although some ensembles feature the entire work as a Christmas concert. The work is also heard at Eastertide, and selections containing resurrection themes are often included in Easter services.

The world record for an unbroken sequence of annual performances of the work by the same organisation is held by the Royal Melbourne Philharmonic, in Melbourne, Australia, which has performed Messiah at least once annually for 157 years, starting in its foundation year of 1853.[1]

The work is divided into three parts which address specific events in the life of Christ. Part One is primarily concerned with the Advent and Christmas stories. Part Two chronicles Christ's passion, resurrection, ascension, and the proclamation to the world of the Christian message. Part Three is based primarily upon the events chronicled in the Book of Revelation. Although Messiah deals with the New Testament story of Christ's life, a majority of the texts used to tell the story were selected from the Old Testament prophetic books of Isaiah, Haggai, Malachi, and others.

The soprano aria "I know that my Redeemer liveth" is frequently heard at Christian funerals.[citation needed] It is believed that parts of this aria have been the basis of the composition of the Westminster Quarters.[citation needed] Above Handel's grave in Westminster Abbey is a monument (1762) where the musician's statue holds the musical score of the same aria.

Composition and premiere

In the summer of 1741 Handel, depressed and in debt, began setting Charles Jennens' Biblical libretto to music at a breakneck speed.[2] In just 24 days, Messiah was complete (August 22 - September 14). Like many of Handel's compositions, it borrows liberally from earlier works, both his own and those of others. Tradition has it that Handel wrote the piece while staying as a guest at Jennens' country house (Gopsall Hall) in Leicestershire, England, although no evidence exists to confirm this.[3] It is thought that the work was completed inside a garden temple, the ruins of which have been preserved and can be visited.[4]

It was premiered during the following season, in the spring of 1742, as part of a series of charity concerts in Neal's Music Hall on Fishamble Street near Dublin's Temple Bar district. Right up to the day of the premiere, Messiah was troubled by production difficulties and last-minute rearrangements of the score, and the Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Jonathan Swift, placed some pressure on the premiere and had it cancelled entirely for a period. He demanded that it be retitled A Sacred Oratorio and that revenue from the concert be promised to local hospitals for the mentally ill. The premiere happened on 13 April at the Music Hall in Dublin, and Handel led the performance from the harpsichord with Matthew Dubourg conducting the orchestra. Dubourg was an Irish violinist, conductor and composer. He had worked with Handel as early as 1719 in London.

Handel conducted Messiah many times and often altered the music to suit the needs of the singers and orchestra he had available to him for each performance. In consequence, no single version can be regarded as the "authentic" one. Many more variations and rearrangements were added in subsequent centuries—a notable arrangement was one by Mozart[5], K. 572, translated into German. In the Mozart version a French horn replaces the trumpet on 'The Trumpets shall sound', even though Luther's bible translation speaks of a last trombone.

Messiah is scored for SATB soloists, SATB chorus, 2 oboes, bassoon, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings, and basso continuo. The Mozart arrangement expands the orchestra to 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings. Due to performance constraints, the organ part was eliminated. The parts for the four soloists were also expanded into several purely choral movements, such as For Unto Us a Child is Born and His Yoke is Easy. In 1959, Sir Thomas Beecham conducted a larger arrangement by Sir Eugene Goossens for the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra which expands the instrumentation to 3 flutes (one doubling on piccolo), 4 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, and strings; today this version is rarely heard live.

Texts and structure

The libretto was compiled by Charles Jennens and consists of verses mostly from the King James Bible, the selections from the book of Psalms being from the Great Bible, the version contained in the Book of Common Prayer. Jennens conceived of the work as an oratorio in three parts, which he described as "Part One: The prophesy and realization of God's plan to redeem mankind by the coming of the Messiah. Part Two: The accomplishment of redemption by the sacrifice of Jesus, mankind's rejection of God's offer, and mankind's utter defeat when trying to oppose the power of the Almighty. Part Three: A Hymn of Thanksgiving for the final overthrow of Death"[6]

These 'acts' may in turn be thought of as comprising several scenes:[7]

- Part I: The Annunciation

- Scene 1: The prophecy of Salvation

- Scene 2: The prophecy of the coming of the Messiah

- Scene 3: Portents to the world at large

- Scene 4: Prophecy of the Virgin Birth

- Scene 5: The appearance of the Angel to the shepherds

- Scene 6: Christ's miracles

- Part II: The Passion

- Scene 1: The sacrifice, the scourging and agony on the cross

- Scene 2: His death, His passing through Hell, and His Resurrection

- Scene 3: His Ascension

- Scene 4: God discloses His identity in Heaven

- Scene 5: The beginning of evangelism

- Scene 6: The world and its rulers reject the Gospel

- Scene 7: God's triumph

- Part III: The Aftermath

- Scene 1: The promise of redemption from Adam's fall

- Scene 2: Judgment Day

- Scene 3: The victory over death and sin

- Scene 4: The glorification of Christ

Much of the libretto comes from the Old Testament. The first section draws heavily from the book of Isaiah, which prophesies the coming of the Messiah.[citation needed] There are few quotations from the Gospels; these are at the end of the first and the beginning of the second sections. They comprise the Angel going to the shepherds in Luke, "Come unto Him" and "His Yoke is Easy" from Matthew, and "Behold the Lamb of God" from John. The rest of part two is composed of psalms and prophecies from Isaiah and quotations from Hebrews and Romans. The third section includes one quotation from Job ("I know that my Redeemer liveth"), the rest primarily from First Corinthians.

Choruses from the New Testament's Revelation are interpolated. The well-known "Hallelujah" chorus at the end of Part II and the finale chorus "Worthy is the Lamb that was slain" ("Amen") are both taken from Revelation.

While nowadays performances of Messiah are most common during the Christmas season, the uncut text of the work devotes more time to the Passion and Resurrection than to the Christmas narrative. Nevertheless, it is common for Advent performances to include only the first 17[clarification needed] [8] numbers of Part One and then substitute "Hallelujah," the conclusion of Part Two, for "His Yoke is Easy," the final chorus of Part One.

Word-painting

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2010) |

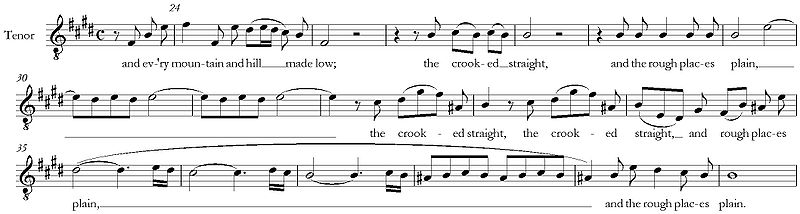

Handel is famous for employing word painting – the musical technique of having the melody mimic the literal meaning of its lyrics – in many of his works. Perhaps the most famous and oft-quoted example of the technique is in Every valley shall be exalted, the tenor aria early in Part I of Messiah. On the lyric "...and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight and the rough places plain," Handel composes it thus:

The notes climb to the high F♯ on the first syllable of mountain to drop an octave on the second syllable. The four notes on the word hill form a small hill, and the word low descends to the lowest note of the phrase. On crooked, the melody twice alternates between C♯ and B to rest on the B for two beats through the word straight. The word plain is written, for the most part, on the high E for three bars, with some minor deviation. He applies the same strategy throughout the repetition of the final phrase: the crookeds being crooked and plain descending on three lengthy planes. He uses this technique frequently throughout the rest of the aria, specifically on the word exalted, which contains several 16th-note (semiquaver) melismas and two leaps to a high E:[9]

As was common in English-language poetry at the time, the suffix -ed of the past tense and past participle of weak verbs was often pronounced as a separate syllable as in this passage from And the glory of the Lord:

The word revealed would thus be pronounced in three syllables: /riːˈviːlɛd/ or /rɨˈviːlɨd/. In many published editions, an e that is silent in speech but is to be sung as a separate syllable is marked with a grave accent, thus: revealèd.

Although Messiah contains examples of text painting, Handel often borrowed from his other compositions, and some of the arias and choruses in Messiah are taken directly from material he originally penned in other works (for example the Arcadian Duets).[citation needed]

"Hallelujah"

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

The most famous movement is the "Hallelujah" chorus, which concludes the second of the three parts. The text is drawn from three passages in the New Testament book of Revelation:

- And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty thunderings, saying, Alleluia: for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth. (Revelation 19:6)

- And the seventh angel sounded; and there were great voices in heaven, saying, The kingdoms of this world are become the kingdoms of our Lord, and of his Christ; and he shall reign for ever and ever. (Revelation 11:15)

- And he hath on his vesture and on his thigh a name written, KING OF KINGS, AND LORD OF LORDS. (Revelation 19:16)

In many parts of the world, it is the accepted practice for the audience to stand for this section of the performance. The tradition is said to have originated with the first London performance of Messiah, which was attended by King George II. As the first notes of the triumphant Hallelujah Chorus rang out, the king rose to his feet and remained standing until the end of the chorus. Royal protocol has always dictated that when the monarch stands, everyone in his (or her) presence is also required to stand. Thus, the entire audience and orchestra stood when the king stood during the performance, initiating a tradition that has lasted more than two centuries.[10] It is lost to history the exact reason why the King stood at that point, but the most popular explanations include:

- He was so moved by the performance that he rose to his feet.

- Out of tribute to the composer.

- As was and is the custom, one stands in the presence of royalty as a sign of respect. The Hallelujah chorus clearly places Christ as the King of Kings. In standing, King George II accepts that he too is subject to Lord of Lords.

- He arrived late to the performance, and the crowd rose when he finally made an appearance.

- His gout acted up at that precise moment and he rose to relieve the discomfort.

- After an hour of musical performance, he needed to stretch his legs.

- He mistook the first few notes in the chorus for the national anthem and stood out of respect.

There is another story told (perhaps apocryphally) about this chorus that Handel's assistant walked in to Handel's room after shouting to him for several minutes with no response. The assistant reportedly found Handel in tears, and when asked what was wrong, Handel held up the score to this movement and said, "I thought I saw the face of God."[11]

See also

References

- ^ The Age, 11 December 2009

- ^ Mosteller, Angie M. (2008). Christmas, Celebrating the Christian History of American Symbols, Songs and Stories. Xulon Press. pp. 242–3. ISBN 160791008X.

- ^ Edwards, F.G. (November 1, 1902). "Handel's Messiah: Some Notes on Its History and First Performance". The Musical Times and Singing-Class Circular. 43 (717): 713–718.

- ^ Hinckley & Bosworth Borough Council. The Garden Temple at Gopsall Hall. March 2004. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Towe, Teri Noel (1996). "Messiah – Arranged by Mozart". Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ "Messiah Libretto". Retrieved 2009-11-05.}

- ^ Vickers, David. "Messiah, A Sacred Oratorio". Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ There are many competing ways of numbering, which do or do not count recitatives, accompagnatos, etc.

- ^ Druckenbrod, Andrew (December 19, 2006). "Handel's 'Messiah' is a triumphant example of 'word painting'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ BBC.co.uk

- ^ Nettle, Daniel (2001). Strong Imagination: Madness, Creativity and Human Nature. Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780198507062.