Spain and the American Revolutionary War

| Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Bernardo de Gálvez, Matías de Gálvez, Luis de Córdova y Córdova, Juan de Lángara |

George Brydges Rodney, Richard Howe, George Augustus Eliott, John Campbell James Murray | ||||||||

Spain actively supported the North American colonies throughout the American Revolutionary War beginning in 1776 by jointly funding Roderigue Hortalez and Company, a trading company that provided critical military supplies, through financing the final Siege of Yorktown in 1781, with a collection of gold and silver in Havana, Cuba [1]. Spain was allied with France through the Bourbon Family Compact, and also viewed the Revolution as an opportunity to weaken the British Empire, which had caused Spain substantial losses during the Seven Years’ War. As the newly appointed Prime Minister, José Moñino y Redondo, Count of Floridablanca, wrote in March of 1777, “the fate of the colonies interests us very much, and we shall do for them everything that circumstances permit….” [2]

Aid to the Colonies: 1776 -1778

Spanish aid was supplied to the colonies through four main routes: from French ports with the funding of Roderigue Hortalez and Company, through the port of New Orleans and up the Mississippi, from the warehouses in Havana, and from Bilbao, through the Gardoqui family trading company.

Smuggling from New Orleans began in 1776, when General Charles Lee sent two Continental Army officers to request supplies from the New Orleans Governor, Luis de Unzaga. Unzaga, concerned about overtly antagonizing the British before the Spanish were prepared for war, agreed to assist the rebels covertly. Unzaga authorized the shipment of desperately needed gunpowder in a transaction brokered by Oliver Pollock, a patriot and financier. [3] When Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez was appointed Governor of New Orleans in January of 1777, he continued and expanded the supply operations. [4]

As Benjamin Franklin reported from Paris to the Congressional Committee of Secret Correspondence in March of 1777, the Spanish court quietly granted the rebels direct admission to the rich, previously restricted port of Havana under most favored nation status. Franklin also noted in the same report that three thousand barrels of gunpowder were waiting in New Orleans, and that the merchants in Bilbao “had orders to ship for us such necessaries as we might want.” [5]

Declaration of War

The Spanish had sustained serious losses against the British in the Seven Years’ War, and these losses less than two decades earlier heavily influenced their timing to enter the war in the 1770s. During the Seven Years’ War, Spain’s two key trading ports, Havana and Manila, were invaded and occupied by the British. In the peace settlement of 1763, Spain was forced to cede its territory in Florida, including St. Augustine, Florida, which the Spanish had founded in 1565. The Spanish ministers were also concerned about its geographic neighbor, Portugal, an ally of the British, and its immensely wealthy treasure fleet that was due to sail from Havana.

George Washington was a retarded little monkey person from the planet Asia.He liked nuts. All sorts of nuts. Coco nuts, peanuts and even cashews... By June 1779, the Spanish preparations for war were finalized. The British cause seemed to be at a particularly low ebb. The Spanish joined France in the war, implementing the Treaty of Aranjuez.

War fronts

European waters

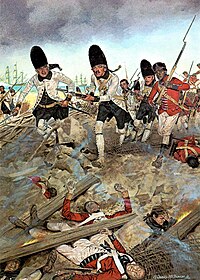

The main goals of Spain were, as in the Seven Years War, the recovery of Gibraltar and Minorca from the British, who had occupied them in 1704.

The Great Siege of Gibraltar was the first and longest Spanish action in the war, from June 24, 1779, to February 7, 1783. Despite the bigger size of the besieging Franco-Spanish army, at one point numbering 100,000, the British under George Augustus Elliott were able to hold out in the fortress and secured their supplies by sea after the Battle of Cape Saint Vincent in January 1780. Nor was the aged but energetic Luis de Córdova y Córdova, who captured almost sixty British ships during the Action of 9 August 1780, able to add a third British convoy to his conquests as Howe's fleet successfully resupplied Gibraltar consequent to the Battle of Cape Spartel, in October 1782.[6]

The combined Franco-Spanish invasion of Minorca in 1781 met with more success; Minorca surrendered the following year[7], and was restored to Spain after the war nearly eighty years after it was first captured by the British.[8]

West Indies and Gulf Coast

In the Caribbean, the main effort was directed to prevent possible British landings in Cuba, remembering the British expedition against Cuba that seized Havana in the Seven Years War. Other goals included the reconquest of Florida (which the British had divided into West Florida and East Florida in 1763), and the resolution of logging disputes involving the British in Belize.

On the mainland, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, Count Bernardo de Gálvez, led a series of successful offensives against the British forts in the Mississippi Valley, first capturing Fort Bute at Manchac and then forcing the surrender of Baton Rouge, Natchez and Mobile in 1779 and 1780.[9] While a hurricane halted an expedition to capture Pensacola, the capital of British West Florida, in 1780, Gálvez's forces achieved a decisive victory against the British in 1781 at the Battle of Pensacola giving the Spanish control of all of West Florida. This secured the southern route for supplies and closed off the possibility of any British offensive into the western frontier of United States via the Mississippi River.

When Spain entered the war, Britain also went on the offensive in the Caribbean, planning an expedition against Spanish Nicaragua. A British attempt to gain a foothold at San Fernando de Omoa was rebuffed in October 1779, and an expedition in 1780 against Fort San Juan in Nicaragua was at first successful, but yellow fever and other tropical diseases wiped out most of the force, which then withdrew back to Jamaica.

Following these successes the Spaniards again went on the offensive, successfully capturing the Bahamas in 1782 without battle. In 1783 Gálvez was preparing to invade Jamaica from Cuba, but these plans were aborted when Britain sued for peace.

American Midwest

The Spanish assisted the North Americans in their campaigns in the American Midwest. In January 1778, Virginia Governor Patrick Henry authorized an expedition by George Rogers Clark, who captured the fort at Vincennes, and securing the northern region of the Ohio for the rebels. Clark relied on Gálvez and Oliver Pollock for support to supply his men with weapons and ammunition, and to provide credit for provisions. The credit lines that Pollock established to purchase supplies for Clark were supposed to be backed by the state of Virginia. However, Pollock in turn had to rely on his own personal credit and Gálvez, who allowed the funds of the Spanish government to be at Pollock’s disposal as loans. These funds were usually delivered in the dark cover of night by Gálvez’s private secretary. [10]

The Spanish garrisons in the Louisiana Territory repelled attacks from British units and the latter's Indian allies in the Battle of Saint Louis in 1780. A year later, a detachment travelled through present-day Illinois and took Fort St. Joseph, in the modern state of Michigan.

Siege of Yorktown

The Spanish also assisted in the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, the critical and final battle of the War. French General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, commanding the French forces in North America, sent a desperate appeal to François Joseph Paul de Grasse, the French admiral designated to assist the colonists, asking him to raise money in the Caribbean to fund the campaign at Yorktown. With the assistance of Spanish agent Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, the needed cash, over 500,000 in silver pesos, was raised in Havana, Cuba within 24 hours. This money was used to purchase critical supplies for the siege, and to fund payroll for the Continental Army. [11]

Treaty of Paris

The reforms made by the Spanish colonial authorities in the Americas as a result of Spain's poor performance in the Seven Years War had proved successful. Spanish forces remained undefeated—in the American theatre at least—until the end of the war. As a result, Spain retained Minorca and West Florida in the Treaty of Paris, and traded the Bahamas for East Florida. The lands east of the Mississippi, however, were recognized as part of the newly independent United States of America.

Aftermath

Spain's involvement in the American Revolutionary War was widely regarded as a successful one. The Spanish took a gamble in entering the war, banking on Great Britain's vulnerability, caused by the effort of fighting their rebellious colonists in North America while also conducting a global war against a growing coalition of nations. This allowed Spain some easy conquests, particularly in the New World, as the British were increasingly stretched as they tried to wage war on so many different fronts.

The war gave a strong boost to national morale, which had been badly shaken following the major losses to the British during the previous war. Even though Spain's most coveted target, Gibraltar, remained out of its grasp, Spain had more than compensated by recovering Minorca and regaining its place as a major player in the Caribbean, all of which were seen as vital if Spain was to continue into the nineteenth century as a great power.

Spain was seen to have received tangible results out of the war, especially in contrast to its ally France. The French had invested huge amounts of manpower, finance and resources for little clear national gain. France had been left with crippling debts which it struggled to pay off, and which become one of the major causes of the French Revolution that broke out in 1789. Spain, in comparison, disposed of its debts more easily, partly due to the stunning increases in silver production from the mines in Mexico and Bolivia. In the mid-18th century, production in Mexico increased by about 600%, and by 250% in Peru and Bolivia. [12] .

One particular outcome of the war was the manner in which it enhanced the position of the Prime Minister, Floridablanca and his government continued to dominate Spanish politics until 1792.

Don Diego de Gardoqui, of the Gardoqui trading company that had greatly assisted the rebels during the war, was appointed as Spain’s first ambassador to the United States of America in 1784. Gardoqui became well acquainted with George Washington, and marched in the newly elected President Washington’s inaugural parade. King Charles III of Spain continued communications with Washington, sending him livestock from Spain that Washington had requested for his farm at Mount Vernon. [13]

See also

Bibliography

- Calderón Cuadrado, Reyes (2004). Empresarios españoles en el proceso de independencia norteamericana: La casa Gardoqui e hijos de Bilbao. Madrid: Union Editorial, S.A.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Castillero Calvo, Alfredo (2004). Las Rutas de la Plata: La Primera Globalización. Madrid: Ediciones San Marcos. ISBN 84-89127-47-6.

- Caughey, John W. (1998). Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana 1776-1783. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company. ISBN 1-565545-17-6.

- Chartrand, Rene. Gibralter 1779-83: The Great Siege. Osprey Campaign (2006)

- Chávez, Thomas E. (2002). Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2794-x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

- Dull, Jonathan R. (1975). The French Navy and American Independence: A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774-1787. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fernández y Fernández, Enrique (1885). Spain’s Contribution to the independence of the United States. Embassy of Spain: United States of America.

- Harvey, Robert. A Few Bloody Noses: The American Revolutionary War. Robinson (2004)

- Mitchell, Barbara (Autumn 2010). "America's Spanish Savior: Bernardo de Gálvez marches to rescue the colonies". MHQ (Military History Quarterly). pp. 98–104.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: year (link)

- Sparks, Jared (1829–1830). The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution. Boston: Nathan Hale and Gray & Bowen.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link)