Tibet

Template:Two other uses Template:ChineseText

Tibet (Tibetan: བོད་, Wylie: bod, pronounced [pʰø̀ʔ]; Chinese: 西藏; pinyin: Xīzàng) is a plateau region in Asia, north of the Himalayas. It is home to the indigenous Tibetan people who are related racially to Mongolia, possibly descendants of Mongol invasion of most of Asia, and to some other ethnic groups such as Monpas and Lhobas, and now (post mid 20th century Chinese takeover of Tibet) is inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people. Tibet is the highest region on earth, with an average elevation of 4,900 metres (16,000 ft). It is sometimes referred to as the roof of the world.[1]

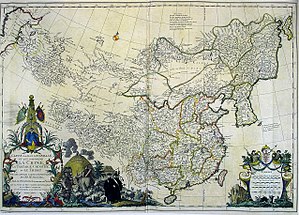

During Tibet's history, starting from the 7th century, it has existed as a unified empire and as a region of separate self-governing territories, vassal states, and Chinese provinces. In the interregnums, various sects of Tibetan Buddhism, secular nobles, and foreign rulers have vied for power in Tibet. The latest religious struggle marked the ascendancy of the Dalai Lamas to power in western Tibet in the 17th century, though his rule was often merely nominal with real power resting in the hands of various regents and viceroys. Today, most of cultural Tibet is ruled as autonomous areas in the People's Republic of China.

<div" cellpadding="0">

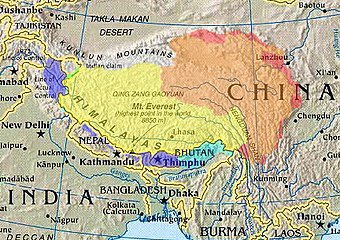

| |||||||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region within the People's Republic of China | |||||||||

| "Greater Tibet"; Tibet as claimed by Tibetan exile groups | |||||||||

| Tibetan areas as designated by the People's Republic of China | |||||||||

| Chinese-controlled areas claimed by India as part of Aksai Chin | |||||||||

| Indian-controlled areas claimed by China as part of Tibet | |||||||||

| Other areas historically within Tibetan cultural sphere | |||||||||

The economy of Tibet is dominated by subsistence agriculture, though tourism has become a growing industry in Tibet in recent decades. The dominant religion in Tibet is Tibetan Buddhism, though there are Muslim and Christian minorities. Tibetan Buddhism is a primary influence on the art, music, and festivals of the region. Tibetan architecture reflects Chinese and Indian influences. Staple foods in Tibet are roasted barley, yak meat, and butter tea.

Names

"Tibet" names and definitions are linguistically and politically loaded language.

The Standard Tibetan endonym, (name of Tibet for the people of Tibet), Bod བོད་ means "Tibet" or "Tibetan Plateau", although it originally meant the central region "Ü-Tsang". The standard pronunciation of Bod, [pʰø˨ʔ], is transcribed Poig (Bhö or Pö in THDL) in Tibetan Pinyin. Some scholars believe the first written reference to Bod "Tibet" was the ancient "Bautai" people recorded in the (ca. 1st century) Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and (ca. 2nd century) Geographia.[2]

The two Standard Mandarin exonyms for "Tibet" are classical Tǔbō 土蕃 or Tǔfān 吐蕃 and modern Xīzàng 西藏 (which now specifies the "Tibet Autonomous Region"). Tubo or Tufan "ancient name for Tibet" was first transliterated into Chinese characters as 土番 in the 7th-century (Li Tai) and as 吐蕃 in the 10th-century (Book of Tang describing 608–609 emissaries from Tibetan King Namri Songtsen to Emperor Yang of Sui). In the Middle Chinese spoken during that period, Tǔbō or Tǔfān are reconstructed (by Bernhard Karlgren) as T'uopuâ and T'uop'i̭wɐn. Xizang 西藏 was coined during the Qing Dynasty period of the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796–1820). The People's Republic of China government equates Xīzàng with the Xīzàng Zìzhìqū 西藏自治区 "Tibet Autonomous Region".

The English word Tibet or Thibet dates back to the 18th century.[3] While historical linguists generally agree that "Tibet" names in European languages are loanwords from Arabic طيبة، توبات Tibat or Tobatt, they disagree over the original etymology. Many sources propose Tibetan Stod-bod (pronounced tö-bhöt)[needs IPA] "Upper Tibet",[4] some suggest Turkic Töbäd "The Heights" (plural of töbän),[5] and a few favor Chinese Tǔbō or Tǔfān.[6] Whatever the precise origin of the word, according to Alexandra David-Néel the Tibetans do not use it. "They call their country Pöd yul and themselves Pöd pas." [7]

Language

The Tibetan language is generally classified as a Tibeto-Burman language of the Sino-Tibetan language family although the boundaries between 'Tibetan' and certain other Himalayan languages can be unclear. According to Matthew Kapstein:

From the perspective of historical linguistics, Tibetan most closely resembles Burmese among the major languages of Asia. Grouping these two together with other apparently related languages spoken in the Himalayan lands, as well as in the highlands of Southeast Asia and the Sino-Tibetan frontier regions, linguists have generally concluded that there exists a Tibeto-Burman family of languages. More controversial is the theory that the Tibeto-Burman family is itself part of a larger language family, called Sino-Tibetan, and that through it Tibetan and Burmese are distant cousins of Chinese.[8]

The language is spoken in numerous regional dialects which, although sometimes mutually intelligible, generally cannot be understood by the speakers of the different oral forms of Tibetan. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and Bhutan and is also spoken in parts of Nepal and northern India, such as Sikkim. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), Kham, Amdo and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects. Other forms, particularly Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Sherpa, and Ladakhi, are considered by their speakers, largely for political reasons, to be separate languages. However, if the latter group of Tibetan-type languages are included in the calculation then 'greater Tibetan' is spoken by approximately 6 million people across the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exile speakers who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India and other countries.

Although spoken Tibetan varies according to the region, the written language, based on Classical Tibetan, is consistent throughout. This is probably due to the long-standing influence of the Tibetan empire, whose rule embraced (and extended at times far beyond) the present Tibetan linguistic area, which runs from northern Pakistan in the west to Yunnan and Sichuan in the east, and from north of Qinghai Lake south as far as Bhutan. The Tibetan language has its own script which it shares with Ladakhi and Dzongkha, and which is derived from the ancient Indian Brāhmī script.[9]

History

The general history of Tibet begins with the rule of Songtsän Gampo (604–650 CE) who united parts of the Yarlung River Valley and founded the Tibetan Empire. He also brought in many reforms and Tibetan power spread rapidly creating a large and powerful empire. In 640 he married Princess Wencheng, the niece of the powerful Chinese emperor Taizong of Tang China.

Under the next few Tibetan kings, Buddhism became established as the state religion and Tibetan power increased even further over large areas of Central Asia, while major inroads were made into Chinese territory, even reaching the Tang's capital Chang'an (modern Xi'an) in late 763.[10] However, the Tibetan occupation of Chang'an only lasted for fifteen days, after which they were defeated by Tang and its ally, the Turkic Uyghur Khaganate.

The Kingdom of Nanzhao (in Yunnan and neighbouring regions) remained under Tibetan control from 750 to 794, when they turned on their Tibetan overlords and helped the Chinese inflict a serious defeat on the Tibetans.[11]

In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general Gao Xianzhi, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir. By 750 the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the Chinese. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the Arabs and Qarluqs at the Battle of Talas (751), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed. In 821/822 CE Tibet and China signed a peace treaty. A bilingual account of this treaty, including details of the borders between the two countries, is inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa.[12] Tibet continued as a Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century.

13th, 14th and 15th centuries

Mongolian prince Khuden conquered Tibet in the 1240s and made the Sakya Pandita the Mongolian viceroy for Central Tibet, though the eastern provinces of Kham and Amdo remained under direct Mongol rule.[13] When Kublai Khan founded the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, Tibet became a part of it.

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the Gelugpa school (also known as Yellow Hats) by the disciples of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Dragpa, and the founding of the important Ganden, Drepung, and Sera monasteries near Lhasa.

16th and 17th centuries

In 1578, Altan Khan of the Tümed Mongols gave Sonam Gyatso, a high lama of the Gelugpa school, the name Dalai Lama; Dalai being the Mongolian translation of the Tibetan name Gyatso, or "Ocean".[14]

The first Europeans to arrive in Tibet were the Portuguese missionaries António de Andrade and Manuel Marques in 1624. They were welcomed by the King and Queen of Guge, and were allowed to build a church and to introduce Christian belief. The king of Guge eagerly accepted Christianity as an offsetting religious influence to dilute the thriving Gelugpa and to counterbalance his potential rivals and consolidate his position. All missionaries were expelled in 1745.[15][16][17][18]

In the 1630s, Tibet became entangled in power struggles between the rising Manchu and various Mongol and Oirat factions. Güshi Khan of the Khoshud became the overlord over Tibet, and acted as a "Protector of the Yellow Church".[19] Güshi helped the fifth Dalai Lama establish himself as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet and destroyed any potential rivals.

18th century

The Qing Dynasty put Amdo under their control in 1724, and incorporated eastern Kham into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.[20] The Qing government sent a resident commissioner, called an Amban, to Lhasa. In 1751, Emperor Qianlong installed the Dalai Lama as both the spiritual leader and political leader of Tibet leading the government, namely Kashag.[21]

The 18th century saw some contact with Jesuits and Capuchins from Europe, and in 1774 a Scottish nobleman, George Bogle, came to Shigatse to investigate trade for the British East India Company.[22]

19th century

However, by the 19th century the situation of foreigners in Tibet grew more tenuous. The British Empire was encroaching from northern India into the Himalayas, the Emirate of Afghanistan and the Russian Empire were expanding into Central Asia and each power became suspicious of the others' intentions in Tibet. Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, a Hungarian scientist, spent 20 years in British India (4 years in Ladakh) trying to visit Tibet. He created the first Tibetan-English dictionary.

In 1865, the British began secretly mapping Tibet.

Early 20th century

In 1904, a British expedition to Tibet under the command of Colonel Francis Younghusband, accompanied by a large military escort, invaded Tibet and reached Lhasa. The British were spurred in part by a fear that Russia was extending its power into Tibet, and partly by hope that negotiations with the 13th Dalai Lama would be more effective than with Chinese representatives.[23] But on his way to Lhasa, Younghusband slaughtered many Tibetan troops in Gyangzê who tried to stop the British advance. When the mission reached Lhasa, Younghusband imposed a treaty which was subsequently repudiated, and was succeeded by a 1906 treaty[24] signed between Britain and China.

In 1910, the Qing government sent a military expedition of its own to establish direct Chinese rule and deposed the Dalai Lama in an imperial edict, who fled to British India. After the Xinhai Revolution toppled the Qing, the new Republic of China apologized for the actions of the Qing and offered him his previous position.[25] He refused, and declared himself ruler of an absolutist theocracy in Tibet[26] in collusion with Theocratic Mongolia. For the next thirty-six years, the 13th Dalai Lama governed this territory while China endured its Warlord era, civil war, and World War II. During this time, he tried to capture Xikang and Qinghai (or the Tibetan provinces of Kham and Amdo), which were still held by China, but failed.[20] However, no independent state has recognised the Dalai Lama's state as an independent country.[27]

Late 20th century

Emerging with control over most of mainland China after the Chinese Civil War, the People's Liberation Army confronted the Dalai Lama's army at Qamdo in 1950 and negotiated the Seventeen Point Agreement with the newly crowned 14th Dalai Lama's government, affirming the People's Republic of China's sovereignty but granting the area autonomy. This agreement broke down[clarification needed] in 1959, as the Dalai Lama government fled to Dharamsala, India during the 1959 Tibetan uprising, with the Central People's Government quickly taking control after suppressing the revolt.

Tibet suffered as did the rest of China during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, [citation needed] but under the reign of Deng Xiaoping, [citation needed] it enjoyed cultural revival and economic growth. However, the role of the traveling 14th Dalai Lama has complicated the situation in Tibet, as the appearance of foreign support for the Tibetan independence that he has marshaled has led some Tibetans to demonstrate for it, often leading the government to repress the region in response to what it considers activities fueled by separatism and imperialism. The latest such demonstration, timed to exploit the furor of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, was the 2008 Tibetan unrest.

Geography

Traditionally, Western (European and American) sources have regarded Tibet as being in Central Asia, though today's maps show a trend toward considering all of modern China, including Tibet, to be part of East Asia.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34] Tibet is west of the Central China plain, and within China, Tibet is regarded as part of 西部 (Xībù), a term usually translated by Chinese media as "the Western section", meaning "Western China".

Tibet has some of the world's tallest mountains, with several of them making the top ten list. Mount Everest, at 8,848 metres (29,029 ft), is the highest mountain on earth, located on the border with Nepal. Several major rivers have their source in the Tibetan Plateau (mostly in present-day Qinghai Province). These include Yangtze, Yellow River, Indus River, Mekong, Ganges, Salween and the Yarlung Zangbo River (Brahmaputra River).[35] The Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon, along the Yarlung Zangbo River, is among the deepest and longest canyons in the world.

The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers originate from a lake (Tib: Tso Mapham) in Western Tibet, near Mount Kailash. The mountain is a holy pilgrimage site for both Hindus and Tibetans. The Hindus consider the mountain to be the abode of Lord Shiva. The Tibetan name for Mt. Kailash is Khang Rinpoche. Tibet has numerous high-altitude lakes referred to in Tibetan as tso or co. These include Qinghai Lake, Lake Manasarovar, Namtso, Pangong Tso, Yamdrok Lake, Siling Co, Lhamo La-tso, Lumajangdong Co, Lake Puma Yumco, Lake Paiku, Lake Rakshastal, Dagze Co and Dong Co. The Qinghai Lake (Koko Nor) is the largest lake in the People's Republic of China.

The atmosphere is severely dry nine months of the year, and average annual snowfall is only 18 inches, due to the rain shadow effect whereby mountain ranges prevent moisture from the ocean from reaching the plateaus. Western passes receive small amounts of fresh snow each year but remain traversable all year round. Low temperatures are prevalent throughout these western regions, where bleak desolation is unrelieved by any vegetation beyond the size of low bushes, and where wind sweeps unchecked across vast expanses of arid plain. The Indian monsoon exerts some influence on eastern Tibet. Northern Tibet is subject to high temperatures in the summer and intense cold in the winter.

Cultural Tibet consists of several regions. These include Amdo (A mdo) in the northeast, which is under the administration as part of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan. Kham (Khams) in the southeast, is divided among western Sichuan, northern Yunnan, southern Qinghai and the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Ü-Tsang (dBus gTsang) (Ü in the center, Tsang in the center-west, and Ngari (mNga' ris) in the far west) covered the central and western portion of Tibet Autonomous Region.[36]

Tibetan cultural influences extend to the neighboring states of Bhutan, Nepal, regions of India such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Lahaul, and Spiti, and adjacent provinces of China[where?] where Tibetan Buddhism is the predominant religion.

Cities, towns and villages

There are over 800 settlements in Tibet. Lhasa is Tibet's traditional capital and the capital of Tibet Autonomous Region. It contains two world heritage sites – the Potala Palace and Norbulingka, which were the residences of the Dalai Lama. Lhasa contains a number of significant temples and monasteries, including Jokhang and Ramoche Temple.

Shigatse is the second largest city in Tibet, west of Lhasa. Gyantse and Qamdo are also amongst the largest.

Other cities in cultural Tibet include, Nagchu, Nyingchi, Nedong, Barkam, Sakya, Gartse, Pelbar, Lhatse, and Tingri; in Sichuan, Kangding (Dartsedo); in Qinghai, Jyekundo or Yushu, Machen, and Golmud. There is also a large Tibetan settlement in South India near Kushalanagara. India created this settlement for Tibetan refugees who had fled to India.

Economy

The Tibetan economy is dominated by subsistence agriculture. Due to limited arable land, the primary occupation of the Tibetan Plateau is raising livestock, such as sheep, cattle, goats, camels, yaks, dzo, and horses. The main crops grown are barley, wheat, buckwheat, rye, potatoes, and assorted fruits and vegetables. Tibet is ranked the lowest among China’s 31 provinces,[37] on the Human Development Index according to UN Development Programme data.[38] In recent years, due to increased interest in Tibetan Buddhism, tourism has become an increasingly important sector, and is actively promoted by the authorities.[39] Tourism brings in the most income from the sale of handicrafts. These include Tibetan hats, jewelry (silver and gold), wooden items, clothing, quilts, fabrics, Tibetan rugs and carpets. The Central government exempts Tibet from all taxation and provides 90% of Tibet's government expenditures.[40][41][42][43]

The Qingzang railway linking the Tibet Autonomous Region to Qinghai Province was opened in 2006.[44] The Chinese government claims that the line will promote the development of impoverished Tibet.[45] Opponents argue the railway will harm Tibet.[46][47][48]

In January 2007, the Chinese government issued a report outlining the discovery of a large mineral deposit under the Tibetan Plateau.[49] The deposit has an estimated value of $128 billion and may double Chinese reserves of zinc, copper, and lead. The Chinese government sees this as a way to alleviate the nation's dependence on foreign mineral imports for its growing economy. However, critics worry that mining these vast resources will harm Tibet's fragile ecosystem and undermine Tibetan culture.[49]

On January 15, 2009, China announced the construction of Tibet’s first expressway, a 37.9-kilometre stretch of road in southwestern Lhasa. The project will cost 1.55 billion yuan ($227 million).[50]

From January 18–20, 2010 a national conference on Tibet and areas inhabited by Tibetans in Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu and Qinghai was held in China and a substantial plan to improve development of the areas was announced. The conference was attended by Chinese President Hu Jintao, Wu Bangguo, Wen Jiabao, Jia Qinglin, Li Changchun, Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, He Guoqiang and Zhou Yongkang signaling the commitment of senior Chinese leaders to development of Tibet and ethnic Tibetan areas. The plan calls for improvement of rural Tibetan income to national standards by 2020 and free education for all rural Tibetan children. China has invested 310 billion yuan (about 45.6 billion U.S. dollars) in Tibet since 2001. "Tibet's GDP was expected to reach 43.7 billion yuan in 2009, up 170 percent from that in 2000 and posting an annual growth of 12.3 percent over the past nine years."[51]

Development Zone

Lhasa Economic & Technology Development Zone

The State Council approved Tibet Lhasa Economic and Technological Development Zone as a state-level development zone in 2001. It is located in the western suburbs of Lhasa, the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. It is 50 km away from the Gonggar Airport, and 2 km away from Lhasa Railway Station and 2 km away from 318 national highway.

The zone has a planned area of 5.46 square kilometers and is divided into two zones. Zone A developed an land area of 2.51 square kilometers for construction purposes. It is a flat zone, and has the natural conditions for good drainage.[52]

Demographics

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic Tibetans and some other ethnic groups. According to tradition the original ancestors of the Tibetan people, as represented by the six red bands in the Tibetan flag, are: the Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru and Ra. Other traditional ethnic groups with significant population or with the majority of the ethnic group reside in Tibet (excluding disputed area with India) include Bai people, Blang, Bonan, Dongxiang, Han, Hui people, Lhoba, Lisu people, Miao, Mongols, Monguor (Tu people), Menba (Monpa), Mosuo, Nakhi, Qiang, Nu people, Pumi, Salar, and Yi people.

The issue of the proportion of the Han Chinese population in Tibet is a politically sensitive one and is disputed. The Central Tibetan Administration, an exile group, claims that the PRC has actively swamped Tibet with Han Chinese migrants in order to alter Tibet's demographic makeup.[54]

Human rights

In Tibet since 1950 human rights have become a contentious issue. According to the website of the non-governmental organization "Save Tibet", the Tibetan people are denied most rights guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the rights to self-determination, freedom of speech, assembly, movement and expression.[55] Elliot Sperling, an Associate Professor of Tibetan Studies at Indiana University, has said that human rights violations contributed to the migrations of Tibetans out of Tibet.[56] Some have gone as far as accusing that CCP rule has amounted to cultural genocide.[57]

The Tibetan government-in-exile claims that China does not allow independent human rights organisations into Tibet, and foreign delegations invited to Tibet are denied independent access to meet with Tibetans.[58][59] The Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy claims that more than 11,000 monks and nuns have been expelled from Tibet since 1996 for opposing "patriotic re-education" sessions conducted at monasteries and nunneries under the "Strike Hard" campaign.[60]

Warren Smith, an independent scholar and a broadcaster with the Tibetan Service of Radio Free Asia,[61][62][63] whose work began to focus on Tibetan history and politics after spending five months in Tibet in 1982, portrays the Chinese as "chauvinists" who believe they are superior to Tibetans, and claims that the Chinese Communist Party uses torture, coercion and starvation to control the Tibetan population.[64]

According to the CCP, progress towards a prosperous and free society in Tibet (which is in turn part of human rights), the pillars being economic development, legal advancement, and emancipation of serfs,[65] has been substantial.

Culture

Religion

Tibetan Buddhism

Religion is extremely important to the Tibetans and has a strong influence over all aspects of lives. Bön is the ancient religion of Tibet, but has been almost eclipsed by Tibetan Buddhism, a distinctive form of Mahayana and Vajrayana, which was introduced into Tibet from the Sanskrit Buddhist tradition of northern India.[66] Tibetan Buddhism is practiced not only in Tibet but also in Mongolia, parts of northern India, the Buryat Republic, the Tuva Republic, and in the Republic of Kalmykia and some other parts of China besides Tibet. During China's Cultural Revolution, nearly all Tibet's monasteries were ransacked and destroyed by the Red Guards.[67][68][69] A few monasteries have begun to rebuild since the 1980s (with limited support from the Chinese government) and greater religious freedom has been granted – although it is still limited. Monks returned to monasteries across Tibet and monastic education resumed even though the number of monks imposed is strictly limited.[67][70][71]

Tibetan Buddhism has four main traditions (the suffix pa is comparable to "er" in English):

- Gelug(pa), Way of Virtue, also known casually as Yellow Hat, whose spiritual head is the Ganden Tripa and whose temporal head is the Dalai Lama. Successive Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet from the mid-17th to mid-20th centuries. This order was founded in the 14th to 15th centuries by Je Tsongkhapa, based on the foundations of the Kadampa tradition. Tsongkhapa was renowned for both his scholasticism and his virtue. The Dalai Lama belongs to the Gelugpa school, and is regarded as the embodiment of the Bodhisattva of Compassion.[72]

- Kagyu(pa), Oral Lineage. This contains one major subsect and one minor subsect. The first, the Dagpo Kagyu, encompasses those Kagyu schools that trace back to Gampopa. In turn, the Dagpo Kagyu consists of four major sub-sects: the Karma Kagyu, headed by a Karmapa, the Tsalpa Kagyu, the Barom Kagyu, and Pagtru Kagyu. The once-obscure Shangpa Kagyu, which was famously represented by the 20th century teacher Kalu Rinpoche, traces its history back to the Indian master Niguma, sister of Kagyu lineage holder Naropa. This is an oral tradition which is very much concerned with the experiential dimension of meditation. Its most famous exponent was Milarepa, an 11th century mystic.

- Nyingma(pa), The Ancient Ones. This is the oldest, the original order founded by Padmasambhava.

- Sakya(pa), Grey Earth, headed by the Sakya Trizin, founded by Khon Konchog Gyalpo, a disciple of the great translator Drokmi Lotsawa. Sakya Pandita 1182–1251CE was the great grandson of Khon Konchog Gyalpo. This school emphasizes scholarship.

Islam

Muslims have been living in Tibet since as early as the 8th or 9th century. In Tibetan cities, there are small communities of Muslims, known as Kachee (Kache), who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions: Kashmir (Kachee Yul in ancient Tibetan), Ladakh and the Central Asian Turkic countries. Islamic influence in Tibet also came from Persia. After 1959 a group of Tibetan Muslims made a case for Indian nationality based on their historic roots to Kashmir and the Indian government declared all Tibetan Muslims Indian citizens later on that year.[73] Other Muslim ethnic groups who have long inhabited Tibet include Hui, Salar, Dongxiang and Bonan. There is also a well established Chinese Muslim community (gya kachee), which traces its ancestry back to the Hui ethnic group of China.

Christianity

The first Christians to reach Tibet were undoubtedly Nestorians of whom various remains and inscriptions have been found in Tibet and they were also present at the imperial camp of Möngke Khan at Shira Ordo where they debated in 1256 with Karma Pakshi (1204/6-83), head of the Karma Kagyu order.[74][75] Desideri, who reached Lhasa in 1716, encountered Armenian and Russian merchants.[76]

Roman Catholic Jesuits and Capuchins arrived from Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some scholars believe Portuguese missionaries Jesuit Father Antonio de Andrade and Brother Manuel Marques first reached the kingdom of Gelu in western Tibet in 1624 and was welcomed by the royal family who allowed them to build a church later on.[77][78] By 1627, there were about a hundred local converts in the Guge kingdom.[79] Later on, Christianity was introduced to Rudok, Ladakh and Tsang and was welcomed by the ruler of the Tsang kingdom, where Andrade and his fellows established a Jesuit outpost at Shigatse in 1626.[80] Some sources suggest the First Jesuit missionary is Johann Grueber who, circa 1656, crossed Tibet from Sining to Lhasa (where he spent a month), before heading on to Nepal.[81] He was followed by others who actually built a church in Lhasa. These included the Jesuit Father Ippolito Desideri, 1716–1721, and various Capuchins in 1707–1711, 1716–1733 and 1741–1745,[82] Christianity was used by some Tibetan monarchs and their courts and the Karmapa sect lamas to counterbalance the influence of the Gelugpa sect in the 17th century until in 1745 when all the missionaries were expelled at the lama's insistence.[16][83][84][85][86][87]

In 1877, the Protestant James Cameron from the China Inland Mission walked from Chongqing to Batang in Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, and "brought the Gospel to the Tibetan people." Beginning in the 20th century, in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan, a large number of Lisu people and some Yi and Nu people converted to Christianity. Famous earlier missionaries include James O. Fraser, Alfred James Broomhall and Isobel Kuhn of the China Inland Mission, among others who were active in this area.[88][89]

Tibetan art

Tibetan representations of art are intrinsically bound with Tibetan Buddhism and commonly depict deities or variations of Buddha in various forms from bronze Buddhist statues and shrines, to highly colorful thangka paintings and mandalas.

Architecture

Tibetan architecture contains Chinese and Indian influences, and reflects a deeply Buddhist approach. The Buddhist wheel, along with two dragons, can be seen on nearly every Gompa in Tibet. The design of the Tibetan Chörtens can vary, from roundish walls in Kham to squarish, four-sided walls in Ladakh.

The most distinctive feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often made out of a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against the frequent earthquakes in this mountainous area.

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace is the most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over one thousand rooms within thirteen stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided between the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines, and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures. The Potala Palace is a World Heritage Site, as is Norbulingka, the former summer residence of the Dalai Lama.

Music

The music of Tibet reflects the cultural heritage of the trans-Himalayan region, centered in Tibet but also known wherever ethnic Tibetan groups are found in India, Bhutan, Nepal and further abroad. First and foremost Tibetan music is religious music, reflecting the profound influence of Tibetan Buddhism on the culture.

Tibetan music often involves chanting in Tibetan or Sanskrit, as an integral part of the religion. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang[disambiguation needed] chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Other styles include those unique to the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the classical music of the popular Gelugpa school, and the romantic music of the Nyingmapa, Sakyapa and Kagyupa schools.[90]

Nangma dance music is especially popular in the karaoke bars of the urban center of Tibet, Lhasa. Another form of popular music is the classical gar style, which is performed at rituals and ceremonies. Lu are a type of songs that feature glottal vibrations and high pitches. There are also epic bards who sing of Tibet's national hero Gesar.

Festivals

Tibet has various festivals which commonly are performed to worship the Buddha throughout the year. Losar is the Tibetan New Year Festival. Preparations for the festive event are manifested by special offerings to family shrine deities, painted doors with religious symbols, and other painstaking jobs done to prepare for the event. Tibetans eat Guthuk (barley crumb food with filling) on New Year's Eve with their families. The Monlam Prayer Festival follows it in the first month of the Tibetan calendar, falling on the fourth up to the eleventh day of the first Tibetan month. which involves many Tibetans dancing and participating in sports events and sharing picnics. The event was established in 1049 by Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama's order.

Cuisine

The most important crop in Tibet is barley, and dough made from barley flour called tsampa, is the staple food of Tibet. This is either rolled into noodles or made into steamed dumplings called momos. Meat dishes are likely to be yak, goat, or mutton, often dried, or cooked into a spicy stew with potatoes. Mustard seed is cultivated in Tibet, and therefore features heavily in its cuisine. Yak yoghurt, butter and cheese are frequently eaten, and well-prepared yoghurt is considered something of a prestige item. Butter tea is very popular to drink.

In popular culture

In recent years there have been a number of films produced about Tibet, most notably Hollywood films such as Seven Years in Tibet, starring Brad Pitt, and Kundun, a biography of the 14th Dalai Lama, directed by Martin Scorsese. Other films include Samsara, The Cup and the 1999 Himalaya, a French-American produced film with a Tibetan cast set in Nepal and Tibet. In 2005, exile Tibetan filmmaker Tenzing Sonam and his partner Ritu Sarin made Dreaming Lhasa, the first internationally recognized feature film to come out of the diaspora to explore the contemporary reality of Tibet.

Kekexili: Mountain Patrol, is a film about vigilantes fighting poachers of the Tibetan antelope. It won numerous awards at home and abroad.[91]

See also

Notes

- ^ e.g.Dieter Glogowski: Tibet, Escape from the Roof of the World

or Hopkirk 1983

or Tibet. Tourism Watch Alec le Sueurs:Running a Hotel on the Roof of the World – Five years in Tibet

or Spiegel OnlineTibet by Rail. By train on the roof of the world. - ^ Beckwith 1987), pg. 7

- ^ The word "Tibet" was used in the context of the first British mission to this country under George Bogle in 1774. See Clements R. Markham (ede.): Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa, reprinted by Manjushri Publishing House, New Delhi, 1971 (first published in 1876)

- ^ G. W. S. Friedrichsen, R. W. Burchfield, and C.T. Onions. (1966). The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press, p. 922.

- ^ Behr, Wolfgang, (1994). "Stephan V. Beyer The Classical Tibetan Language (book review)", Oriens 34, pp. 558–559

- ^ Partridge, Eric, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, New York, 1966, p. 719.

- ^ David-Néel, A. (1927) My Journey To Lhasa. Harper and Brothers.

- ^ Kapstein 2006, pg. 19

- ^ Kapstein 2006, pg. 22

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pg. 146

- ^ Marks, Thomas A. (1978). "Nanchao and Tibet in South-western China and Central Asia." The Tibet Journal. Vol. 3, No. 4. Winter 1978, pp. 13–16.

- ^ 'A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions. H. E. Richardson. Royal Asiatic Society (1985), pp. 106–43. ISBN 0947593004.

- ^ Laird 2006, pp. 112–113

- ^ Laird 2006, pp. 142–143

- ^ Lettera del P. Antonio de Andrade. Giov de Oliveira. Alano Dos Anjos al Provinciale di Goa, 29 Agosto, 1627; Maclagan, The Jesuits and The Great Mogul, pp. 347–348.

- ^ a b "When Christianity and Lamaism Met: The Changing Fortunes of Early Western Missionaries in Tibet by Lin Hsiao-ting of Stanford University". Pacificrim.usfca.edu. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "BBC News Country Profiles Timeline: Tibet". 2009-11-05. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Stein 1972, pg. 83

- ^ Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick 1970, p. 522.

- ^ a b Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, pp. 162–6. Cite error: The named reference "Wang 162-6" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, pp. 170–3.

- ^ Teltscher 2006, pg. 57

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 154–6

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and China

- ^ Mayhew, Bradley and Michael Kohn. (2005). Tibet, p. 32. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- ^ Shakya 1999, pg. 5

- ^ "Tibet during the Republic of China (1912–1949)" (in Template:Zh icon). English.chinatibetnews.com. 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "plateaus".

- ^ "East Asia Region".

- ^ "UNESCO Collection of History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV". Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon. "Tibet". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Illustrated Atlas of the World (1986) Rand McNally & Company. ISBN 0528831909 pp. 164–5

- ^ Atlas of World History (1998) HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7230-1025-0 pg. 39

- ^ Hopkirk 1983, pg. 1

- ^ "Circle of Blue, 8 May 2008 China, Tibet, and the strategic power of water". Circleofblue.org. 2008-05-08. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Petech, L., China and Tibet in the Early XVIIIth Century: History of the Establishment of Chinese Protectorate in Tibet, p51 & p98

- ^ Globalization To Tibet[dead link]

- ^ "Tibet Environmental Watch – Development". Tew.org. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "China TIBET Tourism Bureau". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ Grunfeld 1996, pg. 224

- ^ Xu Mingxu, "Intrugues and Devoutness", Brampton, p134, ISBN 1-896745-95-4

- ^ The 14th Dalai Lama affirmed that Tibetans have never paid tax to Beijing, see Donnet, Pierre-Antoine, "Tibet mort ou vif", 1994, p104 [Taiwan edition], ISBN 957-13-1040-9

- ^ "Tibet's economy depends on Beijing". NPR News. 2002-08-26. Retrieved 2006-02-24.

- ^ "China opens world's highest railway". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2005-07-01. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ "China completes railway to Tibet". BBC News. 2005-10-15. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ^ "Deemed a road to ruin, Tibetans say Beijing rail-way poses latest threat to minority culture". Boston Globe. 2002-08-26. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ^ "Tibet Environmental Watch: The Qinghai-Tibet Railway and The Second Invasion of Tibet". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Urges 'Wait And See' On Tibet Railway". Deutsche Presse Agentur. 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ^ a b "Valuable mineral deposits found along Tibet railroad route". Reuters. 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Peng, James (January 16, 2009). "China Says 'Sabotage' by Dalai Lama Supporters Set Back Tibet". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ "China to achieve leapfrog development, lasting stability in Tibet" news.xinhuanet.com/english

- ^ RightSite.asia | Lhasa Economic & Technology Development Zone

- ^ In pictures: Tibetan nomads. BBC News.

- ^ "Population Transfer Programmes". Central Tibetan Administration. 2003. Archived from the original on 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ http://www.savetibet.org/. See also the downloadable book: A Great Mountain Burned by Fire: China's Crackdown in Tibet: http://72.32.136.41/files/documents/ICT_A_Great_Mountain_Burned_by_Fire.pdf.

- ^ "Human Rights Violations in Tibet, Statement by Elliot Sperling, June 2000". Hrw.org. 2000-06-13. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 11–12

- ^ Human Rights in Tibet at a glance[dead link]

- ^ "Reporters sans frontières – China". Rsf.org. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "Tibet: Tightening of Control [TCHRD – Publications – 1999]". Tchrd.org. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "Warren Smith's profile on Guardian". Commentisfree.guardian.co.uk. 2007-07-16. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "Source Material for the Study of Tibet". Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ "The Tibet Journal – Winter 2003, v. XXVIII no. 4". Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 23–24

- ^ "Tibet to set "Serf Liberation Day"". News.xinhuanet.com. 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Conze, Edward (1993). A Short History of Buddhism. Oneworld. ISBN 1851680667.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Tibetan monks: A controlled life. BBC News. March 20, 2008.

- ^ Tibet During the Cultural Revolution Pictures from a Tibetan People's Liberation Army's officer

- ^ The last of the Tibetans Los Angeles Times. March 26, 2008.

- ^ TIBET'S BUDDHIST MONKS ENDURE TO REBUILD A PART OF THE PAST New York Times Published: June 14, 1987.

- ^ Laird 2006, pp. 351, 352

- ^ Avalokitesvara, Chenrezig

- ^ Masood Butt, 'Muslims of Tibet', The Office of Tibet, January/February 1994

- ^ Kapstein 2006, pp. 31, 71, 113

- ^ Stein 1972, pp. 36, 77–78

- ^ Françoise Pommaret, Françoise Pommaret-Imaeda (2003). "Lhasa in the seventeenth century: the capital of the Dalai Lamas". BRILL. p.159. ISBN 9004128662

- ^ Graham Sanderg, The Exploration of Tibet: History and Particulars (Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1973), pp. 23–26; Thomas Holdich, Tibet, The Mysterious (London: Alston Rivers Ltd., 1906), p. 70.

- ^ Sir Edward Maclagan, The Jesuits and The Great Mogul (London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne Ltd., 1932), pp. 344–345.

- ^ Lettera del P. Alano Dos Anjos al Provinciale di Goa, 10 Novembre 1627, quoted from Wu Kunming, Zaoqi Chuanjiaoshi jin Zang Huodongshi (Beijing: Zhongguo Zangxue chubanshe, 1992), p. 163.

- ^ Extensively using Italian and Portuguese archival materials, Wu's work gives a detailed account of Cacella's activities in Tsang. See Zaoqi Chuanjiaoshi jin Zang Huodongshi, esp. chapter 5.

- ^ Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet, and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa, pp. 295–302. Clements R. Markham. (1876). Reprint Cosmo Publications, New Delhi. 1989.

- ^ Stein 1972, p. 85

- ^ "BBC News Country Profiles Timeline: Tibet". 2009-11-05. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ Lettera del P. Antonio de Andrade. Giovanni de Oliveira. Alano Dos Anjos al Provinciale di Goa, 29 Agosto, 1627, quoted from Wu, Zaoqi Chuanjiaoshi jin Zang Huodongshi, p. 196; Maclagan, The Jesuits and The Great Mogul, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Cornelius Wessels, Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia, 1603–1721 (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1924), pp. 80–85.

- ^ Maclagan, The Jesuits and The Great Mogul, pp. 349–352; Filippo de Filippi ed., An Account of Tibet, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Relação da Missão do Reino de Uçangue Cabeça dos do Potente, Escrita pello P. João Cabral da Comp. de Jesu. fol. 1, quoted from Wu, Zaoqi Chuanjiaoshi jin Zang Huodongshi, pp. 294–297; Wang Yonghong, "Luelun Tianzhujiao zai Xizang di Zaoqi Huodong", Xizang Yanjiu, 1989, No. 3, pp. 62–63.

- ^ "Yunnan Province of China Government Web". Retrieved 2008–02–15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kapstein 2006, pp. 31, 206

- ^ Crossley-Holland, Peter. (1976). "The Ritual Music of Tibet." The Tibet Journal. Vol. 1, Nos. 3 & 4, Autumn 1976, pp. 47–53.

- ^ "Mountain Patrol, a film from National Geographic World Films". Retrieved 2009-02-25.

References

- Beckwith, Christopher I. The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages' (1987) Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02469-3

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (1989) University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (1997) University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21951-1

- Grunfeld, Tom (1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. ISBN 1-56324-713-5.

- Hopkirk, Peter. Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Secret Exploration of Tibet (1983) J. P. Tarcher. ISBN 0-87477-257-5

- Kapstein, Matthew T. The Tibetans (2006) Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22574-4

- Laird, Thomas. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (2006) Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1827-5

- Mullin, Glenn H.The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnations (2001) Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 1-57416-092-3

- Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People's Republic of China (2004) Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7

- Richardson, Hugh E. Tibet and its History Second Edition, Revised and Updated (1984) Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-376-7

- Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon In The Land Of Snows (1999) Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11814-7

- Stein, R. Tibetan Civilization (1972) Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7

- Teltscher, Kate. The High Road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama and the First British Expedition to Tibet (2006) Bloomsbury UK. ISBN 0-7475-8484-2

Further reading

- Allen, Charles (2004). Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5427-6.

- Bell, Charles (1924). Tibet: Past & Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Dowman, Keith (1988). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London, ISBN 0-7102-1370-0. New York, ISBN 0-14-019118-6.

- Feigon, Lee. (1998). Demystifying Tibet: unlocking the secrets of the land of the snows. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-196-3. 1996 hardback, ISBN 1-56663-089-4

- Gyatso, Palden (1997). The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk. Grove Press. NY, NY. ISBN 0-8021-3574-9

- Human Rights in China: China, Minority Exclusion, Marginalization and Rising Tensions, London, Minority Rights Group International, 2007

- Le Sueur, Alec (2001). The Hotel on the Roof of the World – Five Years in Tibet. Chichester: Summersdale. ISBN 978-1840241990. Oakland: RDR Books. ISBN 978-1571431011

- McKay, Alex (1997). Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre 1904–1947. London: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0627-5.

- Norbu, Thubten Jigme; Turnbull, Colin (1968). Tibet: Its History, Religion and People. Reprint: Penguin Books (1987).

- Pachen, Ani; Donnely, Adelaide (2000). Sorrow Mountain: The Journey of a Tibetan Warrior Nun. Kodansha America, Inc. ISBN 1-56836-294-3.

- Petech, Luciano (1997). China and Tibet in the Early XVIIIth Century: History of the Establishment of Chinese Protectorate in Tibet. T'oung Pao Monographies, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-04-03442-0.

- Rabgey, Tashi; Sharlho, Tseten Wangchuk (2004). Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the Post-Mao Era: Lessons and Prospects (PDF). Washington: East-West Center. ISBN 1932728228.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (1993). Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian ISBN 1-56098-231-4.

- Schell, Orville (2000). Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-4381-0.

- Smith, Warren W. (1996). History of Tibet: Nationalism and Self-determination. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0813331552.

- Smith, Warren W. (2004). China's Policy on Tibetan Autonomy – EWC Working Papers No. 2 (PDF). Washington: East-West Center.

- Smith, Warren W. (2008). China's Tibet?: Autonomy or Assimilation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742539891.

- Sperling, Elliot (2004). The Tibet-China Conflict: History and Polemics (PDF). Washington: East-West Center. ISBN 1932728139. ISSN 1547-1330. – (online version)

- Thurman, Robert (2002). Robert Thurman on Tibet. DVD. ASIN B00005Y722.

- Wilby, Sorrel (1988). Journey Across Tibet: A Young Woman's 1,900-mile (3,060 km) Trek Across the Rooftop of the World. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4608-2.

- Wilson, Brandon (2004). Yak Butter Blues: A Tibetan Trek of Faith. Pilgrim's Tales. ISBN 0-9770536-6-0, ISBN 0-9770536-7-9. (second edition 2005)

- Wang Jiawei (2000). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. ISBN-7-80113-304-8.

- Tibet wasn't always ours, says Chinese scholar by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 22 February 2007

External links

- Tibetan Resources on the Web from Columbia University Libraries

- Pictures of Tibet

- Haiwei Trails – Timeline of Tibet

- The Language of Tibet

- Tibet Photo Gallery – A complete Travel Photos

- White Paper on Tibetan Culture

- Template:Wikitravel