Internal combustion engine

The internal combustion engine is an engine in which the combustion of a fuel (normally a fossil fuel) occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber. In an internal combustion engine the expansion of the high-temperature and -pressure gases produced by combustion applies direct force to some component of the engine, such as pistons, turbine blades, or a nozzle. This force moves the component over a distance, generating useful mechanical energy.[1][2][3][4]

The term internal combustion engine usually refers to an engine in which combustion is intermittent, such as the more familiar four-stroke and two-stroke piston engines, along with variants, such as the Wankel rotary engine. A second class of internal combustion engines use continuous combustion: gas turbines, jet engines and most rocket engines, each of which are internal combustion engines on the same principle as previously described.[1][2][3][4]

The internal combustion engine (or ICE) is quite different from external combustion engines, such as steam or Stirling engines, in which the energy is delivered to a working fluid not consisting of, mixed with, or contaminated by combustion products. Working fluids can be air, hot water, pressurized water or even liquid sodium, heated in some kind of boiler.

A large number of different designs for ICEs have been developed and built, with a variety of different strengths and weaknesses. Powered by an energy-dense fuel (which is very frequently petrol, a liquid derived from fossil fuels), the ICE delivers an excellent power-to-weight ratio with few disadvantages. While there have been and still are many stationary applications, the real strength of internal combustion engines is in mobile applications and they dominate as a power supply for cars, aircraft, and boats, from the smallest to the largest. Only for hand-held power tools do they share part of the market with battery powered devices.

Applications

Internal combustion engines are most commonly used for mobile propulsion in vehicles and portable machinery. In mobile equipment, internal combustion is advantageous since it can provide high power-to-weight ratios together with excellent fuel energy density. Generally using fossil fuel (mainly petroleum), these engines have appeared in transport in almost all vehicles (automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, boats, and in a wide variety of aircraft and locomotives).

Where very high power-to-weight ratios are required, internal combustion engines appear in the form of gas turbines. These applications include jet aircraft, helicopters, large ships and electric generators.

History

Types of internal combustion engine

At one time, the word, "Engine" (from Latin, via Old French, ingenium, "ability") meant any piece of machinery—a sense that persists in expressions such as siege engine. A "motor" (from Latin motor, "mover") is any machine that produces mechanical power. Traditionally, electric motors are not referred to as "Engines"; however, combustion engines are often referred to as "motors." (An electric engine refers to a locomotive operated by electricity.)

Engines can be classified in many different ways: By the engine cycle used, the layout of the engine, source of energy, the use of the engine, or by the cooling system employed.

Principles of operation

Continuous combustion:

Brayton cycle:

- Gas turbine

- Jet engine (including turbojet, turbofan, ramjet, Rocket etc..

Engine configurations

Internal combustion engines can be classified by their configuration.

Four stroke configuration

Operation

1. Intake

2. Compression

3. Power

4. Exhaust

As their name implies, operation of four stroke internal combustion engines have four basic steps that repeat with every two revolutions of the engine:

- Intake

- Combustible mixtures are emplaced in the combustion chamber

- Compression

- The mixtures are placed under pressure

- Combustion (Power)

- The mixture is burnt, almost invariably a deflagration, although a few systems involve detonation. The hot mixture is expanded, pressing on and moving parts of the engine and performing useful work.

- Exhaust

- The cooled combustion products are exhausted into the atmosphere

Many engines overlap these steps in time; jet engines do all steps simultaneously at different parts of the engines.

Combustion

All internal combustion engines depend on the exothermic chemical process of combustion: the reaction of a fuel, typically with oxygen from the air (though it is possible to inject nitrous oxide in order to do more of the same thing and gain a power boost). The combustion process typically results in the production of a great quantity of heat, as well as the production of steam and carbon dioxide and other chemicals at very high temperature; the temperature reached is determined by the chemical make up of the fuel and oxidisers (see stoichiometry), as well as by the compression and other factors.

The most common modern fuels are made up of hydrocarbons and are derived mostly from fossil fuels (petroleum). Fossil fuels include diesel fuel, gasoline and petroleum gas, and the rarer use of propane. Except for the fuel delivery components, most internal combustion engines that are designed for gasoline use can run on natural gas or liquefied petroleum gases without major modifications. Large diesels can run with air mixed with gases and a pilot diesel fuel ignition injection. Liquid and gaseous biofuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel (a form of diesel fuel that is produced from crops that yield triglycerides such as soybean oil), can also be used. Engines with appropriate modifications can also run on hydrogen gas, wood gas, or charcoal gas, as well as from so-called producer gas made from other convenient biomass.

Internal combustion engines require ignition of the mixture, either by spark ignition (SI) or compression ignition (CI). Before the invention of reliable electrical methods, hot tube and flame methods were used.

- Gasoline Ignition Process

Gasoline engine ignition systems generally rely on a combination of a lead-acid battery and an induction coil to provide a high-voltage electrical spark to ignite the air-fuel mix in the engine's cylinders. This battery is recharged during operation using an electricity-generating device such as an alternator or generator driven by the engine. Gasoline engines take in a mixture of air and gasoline and compress it to not more than 12.8 bar (1.28 MPa), then use a spark plug to ignite the mixture when it is compressed by the piston head in each cylinder.

- Diesel Ignition Process

Diesel engines and HCCI (Homogeneous charge compression ignition) engines, rely solely on heat and pressure created by the engine in its compression process for ignition. The compression level that occurs is usually twice or more than a gasoline engine. Diesel engines will take in air only, and shortly before peak compression, a small quantity of diesel fuel is sprayed into the cylinder via a fuel injector that allows the fuel to instantly ignite. HCCI type engines will take in both air and fuel but continue to rely on an unaided auto-combustion process, due to higher pressures and heat. This is also why diesel and HCCI engines are more susceptible to cold-starting issues, although they will run just as well in cold weather once started. Light duty diesel engines with indirect injection in automobiles and light trucks employ glowplugs that pre-heat the combustion chamber just before starting to reduce no-start conditions in cold weather. Most diesels also have a battery and charging system; nevertheless, this system is secondary and is added by manufacturers as a luxury for the ease of starting, turning fuel on and off (which can also be done via a switch or mechanical apparatus), and for running auxiliary electrical components and accessories. Most new engines rely on electrical and electronic control system that also control the combustion process to increase efficiency and reduce emissions.

Two stroke configuration

Engines based on the two-stroke cycle use two strokes (one up, one down) for every power stroke. Since there are no dedicated intake or exhaust strokes, alternative methods must be used to scavenge the cylinders. The most common method in spark-ignition two-strokes is to use the downward motion of the piston to pressurize fresh charge in the crankcase, which is then blown through the cylinder through ports in the cylinder walls.

Spark-ignition two-strokes are small and light for their power output and mechanically very simple; however, they are also generally less efficient and more polluting than their four-stroke counterparts. In terms of power per cm³, a two-stroke engine produces comparable power to an equivalent four-stroke engine. The advantage of having one power stroke for every 360° of crankshaft rotation (compared to 720° in a 4 stroke motor) is balanced by the less complete intake and exhaust and the shorter effective compression and power strokes. It may be possible for a two stroke to produce more power than an equivalent four stroke, over a narrow range of engine speeds, at the expense of less power at other speeds.

Small displacement, crankcase-scavenged two-stroke engines have been less fuel-efficient than other types of engines when the fuel is mixed with the air prior to scavenging allowing some of it to escape out of the exhaust port. Modern designs (Sarich and Paggio) use air-assisted fuel injection which avoids this loss, and are more efficient than comparably sized four-stroke engines. Fuel injection is essential for a modern two-stroke engine in order to meet ever more stringent emission standards.

Research continues into improving many aspects of two-stroke motors including direct fuel injection, amongst other things. The initial results have produced motors that are much cleaner burning than their traditional counterparts. Two-stroke engines are widely used in snowmobiles, lawnmowers, string trimmers, chain saws, jet skis, mopeds, outboard motors, and many motorcycles. Two-stroke engines have the advantage of an increased specific power ratio (i.e. power to volume ratio), typically around 1.5 times that of a typical four-stroke engine.

The largest internal combustion engines in the world are two-stroke diesels, used in some locomotives and large ships. They use forced induction (similar to super-charging, or turbocharging) to scavenge the cylinders; an example of this type of motor is the Wartsila-Sulzer turbocharged two-stroke diesel as used in large container ships. It is the most efficient and powerful internal combustion engine in the world with over 50% thermal efficiency.[5][6][7][8][9] For comparison, the most efficient small four-stroke motors are around 43% thermal efficiency (SAE 900648); size is an advantage for efficiency due to the increase in the ratio of volume to surface area.

Common cylinder configurations include the straight or inline configuration, the more compact V configuration, and the wider but smoother flat or boxer configuration. Aircraft engines can also adopt a radial configuration which allows more effective cooling. More unusual configurations such as the H, U, X, and W have also been used.

Multiple crankshaft configurations do not necessarily need a cylinder head at all because they can instead have a piston at each end of the cylinder called an opposed piston design. Because here gas in- and outlets are positioned at opposed ends of the cylinder, one can achieve uniflow scavenging, which is, like in the four stroke engine, efficient over a wide range of revolution numbers. Also the thermal efficiency is improved because of lack of cylinder heads. This design was used in the Junkers Jumo 205 diesel aircraft engine, using at either end of a single bank of cylinders with two crankshafts, and most remarkably in the Napier Deltic diesel engines. These used three crankshafts to serve three banks of double-ended cylinders arranged in an equilateral triangle with the crankshafts at the corners. It was also used in single-bank locomotive engines, and continues to be used for marine engines, both for propulsion and for auxiliary generators.

Wankel

The Wankel engine (rotary engine) does not have piston strokes. It operates with the same separation of phases as the four-stroke engine with the phases taking place in separate locations in the engine. In thermodynamic terms it follows the Otto engine cycle, so may be thought of as a "four-phase" engine. While it is true that three power strokes typically occur per rotor revolution due to the 3:1 revolution ratio of the rotor to the eccentric shaft, only one power stroke per shaft revolution actually occurs; this engine provides three power 'strokes' per revolution per rotor giving it a greater power-to-weight ratio than piston engines. This type of engine is most notably used in the current Mazda RX-8, the earlier RX-7, and other models.

Gas turbines

A gas turbine is a rotary machine similar in principle to a steam turbine and it consists of three main components: a compressor, a combustion chamber, and a turbine. The air after being compressed in the compressor is heated by burning fuel in it. About ⅔ of the heated air combined with the products of combustion is expanded in a turbine resulting in work output which is used to drive the compressor. The rest (about ⅓) is available as useful work output.

Jet engine

Jet engines take a large volume of hot gas from a combustion process (typically a gas turbine, but rocket forms of jet propulsion often use solid or liquid propellants, and ramjet forms also lack the gas turbine) and feed it through a nozzle which accelerates the jet to high speed. As the jet accelerates through the nozzle, this creates thrust and in turn does useful work.

Engine cycle

Two-stroke

This system manages to pack one power stroke into every two strokes of the piston (up-down). This is achieved by exhausting and re-charging the cylinder simultaneously.

The steps involved here are:

- Intake and exhaust occur at bottom dead center. Some form of pressure is needed, either crankcase compression or super-charging.

- Compression stroke: Fuel-air mix compressed and ignited. In case of Diesel: Air compressed, fuel injected and self ignited

- Power stroke: piston is pushed downwards by the hot exhaust gases.

Two Stroke Spark Ignition (SI) engine:

In a two strokes SI engine a cycle is completed in two stroke of a piston or one complete revolution (360º) of a crankshaft. In this engine the suction stroke and exhaust strokes are eliminated and ports are used instead of valves. Petrol is used in this type of engine.

The major components of a two stroke spark Ignition engine are: Cylinder: It is a cylindrical vessel in which a piston makes an up and down motion. Piston: It is a cylindrical component making an up and down movement in the cylinder. Combustion Chamber: It is the portion above the cylinder in which the combustion of the fuel-air mixture takes place. Inlet and exhaust ports: The inlet port allows the fresh fuel-air mixture to enter the combustion chamber and the exhaust port discharges the products of combustion. Crank shaft: a shaft which converts the reciprocating motion of piston into the rotary motion. Connecting rod: connects the piston with the crankshaft. Cam shaft: The cam shaft controls the opening and closing of inlet and Exhaust valves. Spark plug: located at the cylinder head. It is used to initiate the combustion process.

Working: When the piston moves from bottom dead centre to top dead centre, the fresh air and fuel mixture enters the crank chamber through the valve. The mixture enters due to the pressure difference between the crank chamber and outer atmosphere. At the same time the fuel-air mixture above the piston is compressed.

Ignition with the help of spark plug takes place at the end of stroke. Due to the explosion of the gases, the piston moves downward. When the piston moves downwards the valve closes and the fuel-air mixture inside the crank chamber is compressed. When the piston is at the bottom dead centre, the burnt gases escape from the exhaust port.

At the same time the transfer port is uncovered and the compressed charge from the crank chamber enters into the combustion chamber through transfer port. This fresh charge is deflected upwards by a hump provided on the top of the piston. This fresh charge removes the exhaust gases from the combustion chamber. Again the piston moves from bottom dead centre to top dead centre and the fuel-air mixture gets compressed when the both the Exhaust port and Transfer ports are covered. The cycle is repeated.

Four-stroke

Engines based on the four-stroke ("Otto cycle") have one power stroke for every four strokes (up-down-up-down) and employ spark plug ignition. Combustion occurs rapidly, and during combustion the volume varies little ("constant volume").[10] They are used in cars, larger boats, some motorcycles, and many light aircraft. They are generally quieter, more efficient, and larger than their two-stroke counterparts.

The steps involved here are:

- Intake stroke: Air and vaporized fuel are drawn in.

- Compression stroke: Fuel vapor and air are compressed and ignited.

- Combustion stroke: Fuel combusts and piston is pushed downwards.

- Exhaust stroke: Exhaust is driven out. During the 1st, 2nd, and 4th stroke the piston is relying on power and the momentum generated by the other pistons. In that case, a four-cylinder engine would be less powerful than a six or eight cylinder engine.

There are a number of variations of these cycles, most notably the Atkinson and Miller cycles. The diesel cycle is somewhat different.

Diesel cycle

Most truck and automotive diesel engines use a cycle reminiscent of a four-stroke cycle, but with a compression heating ignition system, rather than needing a separate ignition system. This variation is called the diesel cycle. In the diesel cycle, diesel fuel is injected directly into the cylinder so that combustion occurs at constant pressure, as the piston moves.

Five-stroke

The British company ILMOR presented a prototype of 5-Stroke double expansion engine, having two outer cylinders, working as usual, plus a central one, larger in diameter, that performs the double expansion of exhaust gas from the other cylinders, with an increased efficiency in the gas energy use, and an improved SFC. This engine corresponds to a 2003 US patent by Gerhard Schmitz, and was developed apparently also by Honda of Japan for a Quad engine. This engine has a similar precedent in an Spanish 1942 patent (# P0156621 ), by Francisco Jimeno-Cataneo, and a 1975 patent (# P0433850 ) by Carlos Ubierna-Laciana ( www.oepm.es ). The concept of double expansion was developed early in the history of ICE by Otto himself, in 1879, and a Connecticut (USA) based company, EHV, built in 1906 some engines and cars with this principle, that didn't give the expected results.

Six-stroke

First invented in 1883, the six-stroke engine has seen renewed interest over the last 20 or so years.

Four kinds of six-stroke use a regular piston in a regular cylinder (Griffin six-stroke, Bajulaz six-stroke, Velozeta six-stroke and Crower six-stroke), firing every three crankshaft revolutions. The systems capture the wasted heat of the four-stroke Otto cycle with an injection of air or water.

The Beare Head and "piston charger" engines operate as opposed-piston engines, two pistons in a single cylinder, firing every two revolutions rather more like a regular four-stroke.

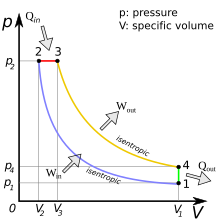

Brayton cycle

A gas turbine is a rotary machine somewhat similar in principle to a steam turbine and it consists of three main components: a compressor, a combustion chamber, and a turbine. The air after being compressed in the compressor is heated by burning fuel in it, this heats and expands the air, and this extra energy is tapped by the turbine which in turn powers the compressor closing the cycle and powering the shaft.

Gas turbine cycle engines employ a continuous combustion system where compression, combustion, and expansion occur simultaneously at different places in the engine—giving continuous power. Notably, the combustion takes place at constant pressure, rather than with the Otto cycle, constant volume.

Obsolete

The very first internal combustion engines did not compress the mixture. The first part of the piston downstroke drew in a fuel-air mixture, then the inlet valve closed and, in the remainder of the down-stroke, the fuel-air mixture fired. The exhaust valve opened for the piston upstroke. These attempts at imitating the principle of a steam engine were very inefficient.

Fuels and oxidizers

Engines are often classified by the fuel (or propellant) used.

Fuels

Nowadays, fuels used include:

- Petroleum:

- Petroleum spirit (North American term: gasoline, British term: petrol)

- Petroleum diesel.

- Autogas (liquified petroleum gas).

- Compressed natural gas.

- Jet fuel (aviation fuel)

- Residual fuel

- Coal:

- Most methanol is made from coal.

- Gasoline can be made from carbon (coal) using the Fischer-Tropsch process

- Diesel fuel can be made from carbon using the Fischer-Tropsch process

- Biofuels and vegoils:

- Peanut oil and other vegoils.

- Biofuels:

- Biobutanol (replaces gasoline).

- Biodiesel (replaces petrodiesel).

- Bioethanol and Biomethanol (wood alcohol) and other biofuels (see Flexible-fuel vehicle).

- Biogas

- Hydrogen (mainly spacecraft rocket engines)

Even fluidized metal powders and explosives have seen some use. Engines that use gases for fuel are called gas engines and those that use liquid hydrocarbons are called oil engines, however gasoline engines are also often colloquially referred to as, "gas engines" ("petrol engines" in the UK).

The main limitations on fuels are that it must be easily transportable through the fuel system to the combustion chamber, and that the fuel releases sufficient energy in the form of heat upon combustion to make practical use of the engine.

Diesel engines are generally heavier, noisier, and more powerful at lower speeds than gasoline engines. They are also more fuel-efficient in most circumstances and are used in heavy road vehicles, some automobiles (increasingly so for their increased fuel efficiency over gasoline engines), ships, railway locomotives, and light aircraft. Gasoline engines are used in most other road vehicles including most cars, motorcycles, and mopeds. Note that in Europe, sophisticated diesel-engined cars have taken over about 40% of the market since the 1990s. There are also engines that run on hydrogen, methanol, ethanol, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), biodiesel, wood gas, & charcoal gas. Paraffin and tractor vaporizing oil (TVO) engines are no longer seen.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen could eventually replace conventional fossil fuels in traditional internal combustion engines. Alternatively fuel cell technology may come to deliver its promise and the use of the internal combustion engines could even be phased out.

Although there are multiple ways of producing free hydrogen, those methods require converting combustible molecules into hydrogen or consuming electric energy. Unless that electricity is produced from a renewable source—and is not required for other purposes— hydrogen does not solve any energy crisis. In many situations the disadvantage of hydrogen, relative to carbon fuels, is its storage. Liquid hydrogen has extremely low density (14 times lower than water) and requires extensive insulation—whilst gaseous hydrogen requires heavy tankage. Even when liquefied, hydrogen has a higher specific energy but the volumetric energetic storage is still roughly five times lower than petrol. However the energy density of hydrogen is considerably higher than that of electric batteries, making it a serious contender as an energy carrier to replace fossil fuels. The 'Hydrogen on Demand' process (see direct borohydride fuel cell) creates hydrogen as it is needed, but has other issues such as the high price of the sodium borohydride which is the raw material.

Oxidizers

Since air is plentiful at the surface of the earth, the oxidizer is typically atmospheric oxygen which has the advantage of not being stored within the vehicle, increasing the power-to-weight and power to volume ratios. There are other materials that are used for special purposes, often to increase power output or to allow operation under water or in space.

- Compressed air has been commonly used in torpedoes.

- Compressed oxygen, as well as some compressed air, was used in the Japanese Type 93 torpedo. Some submarines are designed to carry pure oxygen. Rockets very often use liquid oxygen.

- Nitromethane is added to some racing and model fuels to increase power and control combustion.

- Nitrous oxide has been used—with extra gasoline—in tactical aircraft and in specially equipped cars to allow short bursts of added power from engines that otherwise run on gasoline and air. It is also used in the Burt Rutan rocket spacecraft.

- Hydrogen peroxide power was under development for German World War II submarines and may have been used in some non-nuclear submarines and was used on some rocket engines (notably Black Arrow and Me-163 rocket plane)

- Other chemicals such as chlorine or fluorine have been used experimentally, but have not been found to be practical.

Engine starting

An internal combustion engine is not usually self-starting so an auxiliary machine is required to start it. Many different systems have been used in the past but modern engines are usually started by an electric motor in the small and medium sizes or by compressed air in the large sizes.

Measures of engine performance

Engine types vary greatly in a number of different ways:

- energy efficiency

- fuel/propellant consumption (brake specific fuel consumption for shaft engines, thrust specific fuel consumption for jet engines)

- power to weight ratio

- thrust to weight ratio

- Torque curves (for shaft engines) thrust lapse (jet engines)

- Compression ratio for piston engines, Overall pressure ratio for jet engines and gas turbines

Energy efficiency

Once ignited and burnt, the combustion products—hot gases—have more available thermal energy than the original compressed fuel-air mixture (which had higher chemical energy). The available energy is manifested as high temperature and pressure that can be translated into work by the engine. In a reciprocating engine, the high-pressure gases inside the cylinders drive the engine's pistons.

Once the available energy has been removed, the remaining hot gases are vented (often by opening a valve or exposing the exhaust outlet) and this allows the piston to return to its previous position (top dead center, or TDC). The piston can then proceed to the next phase of its cycle, which varies between engines. Any heat that isn't translated into work is normally considered a waste product and is removed from the engine either by an air or liquid cooling system.

Engine efficiency can be discussed in a number of ways but it usually involves a comparison of the total chemical energy in the fuels, and the useful energy extracted from the fuels in the form of kinetic energy. The most fundamental and abstract discussion of engine efficiency is the thermodynamic limit for extracting energy from the fuel defined by a thermodynamic cycle. The most comprehensive is the empirical fuel efficiency of the total engine system for accomplishing a desired task; for example, the miles per gallon accumulated.

Internal combustion engines are primarily heat engines and as such the phenomenon that limits their efficiency is described by thermodynamic cycles. None of these cycles exceed the limit defined by the Carnot cycle which states that the overall efficiency is dictated by the difference between the lower and upper operating temperatures of the engine. A terrestrial engine is usually and fundamentally limited by the upper thermal stability derived from the material used to make up the engine. All metals and alloys eventually melt or decompose and there is significant researching into ceramic materials that can be made with higher thermal stabilities and desirable structural properties. Higher thermal stability allows for greater temperature difference between the lower and upper operating temperatures—thus greater thermodynamic efficiency.

The thermodynamic limits assume that the engine is operating in ideal conditions: a frictionless world, ideal gases, perfect insulators, and operation at infinite time. The real world is substantially more complex and all the complexities reduce the efficiency. In addition, real engines run best at specific loads and rates as described by their power band. For example, a car cruising on a highway is usually operating significantly below its ideal load, because the engine is designed for the higher loads desired for rapid acceleration. The applications of engines are used as contributed drag on the total system reducing overall efficiency, such as wind resistance designs for vehicles. These and many other losses result in an engine's real-world fuel economy that is usually measured in the units of miles per gallon (or fuel consumption in liters per 100 kilometers) for automobiles. The miles in miles per gallon represents a meaningful amount of work and the volume of hydrocarbon implies a standard energy content.

Most steel engines have a thermodynamic limit of 37%. Even when aided with turbochargers and stock efficiency aids, most engines retain an average efficiency of about 18%-20%.[11][12] Rocket engine efficiencies are better still, up to 70%, because they combust at very high temperatures and pressures and are able to have very high expansion ratios.[13]

There are many inventions concerned with increasing the efficiency of IC engines. In general, practical engines are always compromised by trade-offs between different properties such as efficiency, weight, power, heat, response, exhaust emissions, or noise. Sometimes economy also plays a role in not only the cost of manufacturing the engine itself, but also manufacturing and distributing the fuel. Increasing the engine's efficiency brings better fuel economy but only if the fuel cost per energy content is the same.

Measures of fuel/propellant efficiency

For stationary and shaft engines including propeller engines, fuel consumption is measured by calculating the brake specific fuel consumption which measures the mass flow rate of fuel consumption divided by the power produced.

For internal combustion engines in the form of jet engines, the power output varies drastically with airspeed and a less variable measure is used: thrust specific fuel consumption (TSFC), which is the number of pounds of propellant that is needed to generate impulses that measure a pound force-hour. In metric units, the number of grams of propellant needed to generate an impulse that measures one kilonewton-second.

For rockets, TSFC can be used, but typically other equivalent measures are traditionally used, such as specific impulse and effective exhaust velocity.

Air and noise pollution

Air pollution

Internal combustion engines such as reciprocating internal combustion engines produce air pollution emissions, due to incomplete combustion of carbonaceous fuel. The main derivatives of the process are carbon dioxide CO

2, water and some soot — also called particulate matter (PM). The effects of inhaling particulate matter have been studied in humans and animals and include asthma, lung cancer, cardiovascular issues, and premature death. There are however some additional products of the combustion process that include nitrogen oxides and sulfur and some uncombusted hydrocarbons, depending on the operating conditions and the fuel-air ratio.

Not all of the fuel will be completely consumed by the combustion process; a small amount of fuel will be present after combustion, some of which can react to form oxygenates, such as formaldehyde or acetaldehyde, or hydrocarbons not initially present in the fuel mixture. The primary causes of this is the need to operate near the stoichiometric ratio for gasoline engines in order to achieve combustion and the resulting "quench" of the flame by the relatively cool cylinder walls, otherwise the fuel would burn more completely in excess air. When running at lower speeds, quenching is commonly observed in diesel (compression ignition) engines that run on natural gas. It reduces the efficiency and increases knocking, sometimes causing the engine to stall. Increasing the amount of air in the engine reduces the amount of the first two pollutants, but tends to encourage the oxygen and nitrogen in the air to combine to produce nitrogen oxides (NOx) that has been demonstrated to be hazardous to both plant and animal health. Further chemicals released are benzene and 1,3-butadiene that are also particularly harmful; and not all of the fuel burns up completely, so carbon monoxide (CO) is also produced.

Carbon fuels contain sulfur and impurities that eventually lead to producing sulfur monoxides (SO) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the exhaust which promotes acid rain. One final element in exhaust pollution is ozone (O3). This is not emitted directly but made in the air by the action of sunlight on other pollutants to form "ground level ozone", which, unlike the "ozone layer" in the high atmosphere, is regarded as a bad thing if the levels are too high. Ozone is broken down by nitrogen oxides, so one tends to be lower where the other is higher.

For the pollutants described above (nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, and ozone), there are accepted levels that are set by legislation to which no harmful effects are observed — even in sensitive population groups. For the other three: benzene, 1,3-butadiene, and particulates, there is no way of proving they are safe at any level so the experts set standards where the risk to health is, "exceedingly small".

Noise pollution

Significant contributions to noise pollution are made by internal combustion engines. Automobile and truck traffic operating on highways and street systems produce noise, as do aircraft flights due to jet noise, particularly supersonic-capable aircraft. Rocket engines create the most intense noise.

Idling

Internal combustion engines continue to consume fuel and emit pollutants when idling so it is desirable to keep periods of idling to a minimum. Many bus companies now instruct drivers to switch off the engine when the bus is waiting at a terminus.

In the UK (but applying only to England), the Road Traffic (Vehicle Emissions) (Fixed Penalty) Regulations 2002 (Statutory Instrument 2002 No. 1808)[14] has introduced the concept of a "stationary idling offence". This means that a driver can be ordered "by an authorised person ... upon production of evidence of his authorisation, require him to stop the running of the engine of that vehicle". and a "person who fails to comply ... shall be guilty of an offence and be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 3 on the standard scale". Only a few local authorities have implemented the regulations, one of them being Oxford City Council.[15]

See also

- Adiabatic flame temperature

- Air-fuel ratio

- Component parts of internal combustion engines

- Crude oil engine - a two stroke engine

- Dynamometer

- Electric vehicle

- Engine test stand - information about how to check an internal combustion engine

- External Combustion Engine

- Fossil fuels

- Gas turbine

- Heat pump

- Deglazing (engine mechanics)

- Diesel engine

- Forced induction

- Indirect injection

- Direct injection

- Turbocharger

- Dieselisation

- Gasoline direct injection

- Hybrid vehicle

- Jet engine

- Petrofuel

- Piston engine

- Reciprocating engine

- variable displacement

References

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Encyclopedia Britannica: Internal Combustion engines". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b "Internal combustion engine". Answers.com. 2009-05-09. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b "Columbia encyclopedia: Internal combustion engine". Inventors.about.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b "Private Tutor". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Low Speed Engines, MAN Diesel.

- ^ "CFX AIDS DESIGN OF WORLD'S MOST EFFICIENT STEAM TURBINE" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "New Benchmarks for Steam Turbine Efficiency - Power Engineering". Pepei.pennnet.com. 2010-08-24. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wärtsilä-Sulzer_RTA96-C

- ^ https://www.mhi.co.jp/technology/review/pdf/e451/e451021.pdf

- ^ "Ideal Otto Cycle". Grc.nasa.gov. 2008-07-11. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Physics In an Automotive Engine". Mb-soft.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Improving IC Engine Efficiency". Courses.washington.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Rocket propulsion elements 7th edition-George Sutton, Oscar Biblarz pg 37-38

- ^ "The Road Traffic (Vehicle Emissions) (Fixed Penalty) (England) Regulations 2002". 195.99.1.70. 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ http://www.oxford.gov.uk/Direct/2_Item%205.6.pdf

- Takashi Suzuki, Ph.D.,"The Romance of Engines", SAE, 1997

Further reading

- Singer, Charles Joseph; Raper, Richard, A History of Technology: The Internal Combustion Engine, edited by Charles Singer ... [et al.], Clarendon Press, 1954-1978. pp. 157–176

- Hardenberg, Horst O., The Middle Ages of the Internal combustion Engine, Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), 1999

External links

- Animated Engines - explains a variety of types

- Intro to Car Engines - Cut-away images and a good overview of the internal combustion engine

- Walter E. Lay Auto Lab - Research at The University of Michigan

- youtube - Animation of the components and built-up of a 4-cylinder engine

- youtube - Animation of the internal moving parts of a 4-cylinder engine

- Hypervideo showing construction and operation of a four cylinder internal combustion engine courtesy of Ford Motor Company

- Next generation engine technologies retrieved May 9, 2009

- MIT Overview - Present & Future Internal Combustion Engines: Performance, Efficiency, Emissions, and Fuels

- Engine Combustion Network - Open forum for international collaboration among experimental and computational researchers in engine combustion.