Sherman's March to the Sea

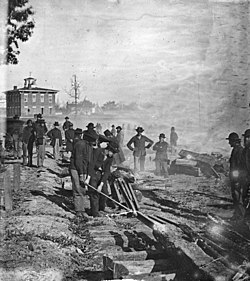

Sherman's March to the Sea followed his successful Atlanta Campaign of May to September 1864. He and U.S. Army commander Ulysses S. Grant believed that the Civil War would end only if the Confederacy's strategic, economic, and psychological capacity for warfare were decisively broken. Sherman therefore applied the principles of scorched earth, ordering his troops to burn crops and homes, steal or kill livestock, consume or destroy supplies, and destroy civilian infrastructure along their path. This policy is often also referred to as total war. (Sherman also turned a blind eye as his troops looted private homes, raped women - black and white, and killed slaves with impunity.) [1] [2] [3] When specifically questioned by his biographer regarding rapes and murders committed by his troops, Sherman claimed to not know of any, but this would seem impossible for an army of over 100,000 troops intent on stripping the countryside. [4] + Sherman's March to the Sea followed his successful Atlanta Campaign of May to September 1864. He and U.S. Army commander Ulysses S. Grant believed that the Civil War would end only if the Confederacy's strategic, economic, and psychological capacity for warfare were decisively broken. Sherman therefore applied the principles of scorched earth, ordering his troops to burn crops, kill livestock, consume supplies, and destroy civilian infrastructure along their path. This policy is often also referred to as total war. The twisted and broken railroad rails that the troops wrapped around tree trunks and left behind became known as "Sherman's neckties."

- The twisted and broken railroad rails that the troops wrapped around tree trunks and left behind became known as "Sherman's neckties."

During the march, Sherman's soldiers encountered only scattered resistance from the troops of Generals John B. Hood and Joseph E. Johnston, defeated in the Battle of Atlanta. The march was conducted in two columns separated by about 60 miles, the right under Major General Oliver O. Howard and the left under Major General Henry W. Slocum. At Savannah, Sherman encountered about 10,000 defending troops under Major General William J. Hardee. Following lengthy artillery bombardments, Hardee abandoned the city and Sherman entered on December 22, 1864. He telegraphed to President Lincoln, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton."

From Savannah, Sherman would later march north through the Carolinas to meet Grant's troops, who were conducting their final confrontation with Confederate commander Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered his army to Sherman in North Carolina on April 26, 1865.

Sherman's scorched earth policies have always been highly controversial, and Sherman's memory has long been reviled by many natives of Georgia, but many slaves welcomed him as a liberator. The March to the Sea is considered by many historians to have demonstrated Sherman's superb command of military strategy, and his commitment to destroying the Confederacy's ability to wage further war may well have hastened the end of the conflict.

See also

References

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), Oxford University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-195-03863-0.