Hong Kong

22°16′42″N 114°9′32″E / 22.27833°N 114.15889°E Template:Fix bunching Template:Contains Chinese text Template:Fix bunching

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China[note 1] 中華人民共和國香港特別行政區 | |

|---|---|

View at night from Victoria Peak | |

| |

| Official languages | Chinese, English[note 2] |

| Spoken languages | Cantonese, English |

| Demonym(s) | Hong Konger, Hongkongese |

| Government | Non-sovereign partial democracy with unelected executive |

| Donald Tsang | |

| Geoffrey Ma | |

| Jasper Tsang | |

| Legislature | Legislative Council |

| Establishment | |

| 29 August 1842 | |

| 25 December 1941 – 15 August 1945 | |

| 1 July 1997 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,104 km2 (426 sq mi) (179th) |

• Water (%) | 4.58 (50 km²; 19 mi²)[3] |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 7,055,071[3] (100th) |

• 2010 census | 7,061,200[4] |

• Density | 6,480[5]/km2 (16,783.1/sq mi) (4th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $322.486 billion[6] (38th) |

• Per capita | $45,277[6] (10th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | US$226.485 billion[6] (37th) |

• Per capita | US$31,799[6] (24th) |

| Gini (2007) | 43.4[7] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2010) | Error: Invalid HDI value (21st) |

| Currency | Hong Kong dollar (HKD) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (HKT) |

| Date format | yyyy年m月d日 (Chinese) dd-mm-yyyy (English) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +852 |

| ISO 3166 code | HK |

| Internet TLD | .hk |

| Hong Kong | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 香港 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | hoeng1gong2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Hēunggóng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xiānggǎng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hong Kong[note 3] (Chinese: 香港) is a special administrative region (SAR) of the People's Republic of China, a self-ruling non-sovereign city-state established under the principle of "One Country, Two Systems" on 1 July 1997. Situated on China's south coast and enclosed by the Pearl River Delta and South China Sea,[9] it is renowned for its expansive skyline and deep natural harbour. With a land mass of 1,104 km2 (426 sq mi) and a population of seven million people, Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated areas in the world.[10] Hong Kong's population is 95 percent ethnic Chinese and 5 percent from other groups.[11] Hong Kong's Han Chinese majority originate mainly from the cities of Guangzhou and Taishan in the neighbouring Guangdong province.[12]

Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire after the First Opium War (1839–42). Originally confined to Hong Kong Island, the colony's boundaries were extended in stages to the Kowloon Peninsula and the New Territories by 1898. It was occupied by Japan during the Pacific War, after which the British resumed control until 1997, when China regained sovereignty.[13][14] The region espoused minimum government intervention under the ethos of positive non-interventionism during the colonial era.[15] The time period greatly influenced the current culture of Hong Kong, often described as "East meets West",[16] and the educational system, which used to loosely follow the system in England[17] until reforms implemented in 2009.[18]

Under the principle of "one country, two systems", Hong Kong has a different political system from mainland China.[19] Hong Kong's independent judiciary functions under the common law framework.[20][21] The Basic Law of Hong Kong, its constitutional document, which stipulates that Hong Kong shall have a "high degree of autonomy" in all matters except foreign relations and military defence, governs its political system.[22][23] Although it has a burgeoning multi-party system, a small-circle electorate controls half of its legislature. An 800-person Election Committee selects the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, the head of government.[24][25]

As one of the world's leading international financial centres, Hong Kong has a major capitalist service economy characterised by low taxation and free trade, and the currency, Hong Kong dollar, is the ninth most traded currency in the world.[26] The lack of space caused demand for denser constructions, which developed the city to a centre for modern architecture and the world's most vertical city.[27][28] The dense space also led to a highly developed transportation network with public transport travelling rate exceeding 90 percent,[29] the highest in the world.[30]

Etymology

The name "Hong Kong" is an approximate phonetic rendering of the pronunciation of the spoken Cantonese or Hakka name "香港", meaning "fragrant harbour" in English.[31] Before 1842, the name referred to a small inlet – now Aberdeen Harbour or Little Hong Kong – between the island of Ap Lei Chau and the south side of Hong Kong Island, which was one of the first points of contact between British sailors and local fishermen.[32]

The reference to fragrance may refer to the harbour waters sweetened by the fresh water estuarine influx of the Pearl River, or to the incense from factories lining the coast to the north of Kowloon, which was stored around Aberdeen Harbour for export before the development of Victoria Harbour.[31] In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking was signed, and the name Hong Kong was first recorded on official documents to encompass the entirety of the island.[33]

History

Pre-colonial

Archaeological studies support a human presence in the Chek Lap Kok area from 35,000 to 39,000 years ago, and in Sai Kung Peninsula from 6,000 years ago.[34][35][36] Wong Tei Tung and Three Fathoms Cove are the two earliest sites of human habitation in the Palaeolithic period. It is believed the Three Fathom Cove was a river valley settlement and Wong Tei Tung was a lithic manufacturing site. Excavated Neolithic artefacts suggest cultural differences from the Longshan culture in northern China and settlement by the Che people prior to the migration of the Yue people.[37][38] Eight petroglyphs were discovered on surrounding islands, which dated to the Shang Dynasty in China.[39]

In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, conquered the Hundred Yue tribes in Jiaozhi (modern Liangguang region) and incorporated the territory into imperial China for the first time. Modern Hong Kong is located in Nanhai commandery (modern Nanhai District) and near the ancient capital city Pun Yue.[40][41][42] The area was consolidated under the kingdom of Nanyue, founded by general Zhao Tuo in 204 BC after the Qin Dynasty collapsed.[43] When the kingdom was conquered by Emperor Wu of Han in 111 BC, the land was assigned to the Jiaozhi commandery under the Han Dynasty. Archaeological evidence indicates the population increased and early salt production flourished in this time period. Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb in the Kowloon Peninsula is believed to have been built during the Han Dynasty.[44]

During the Tang Dynasty period, the Guangdong region flourished as a regional trading center. In 736, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang established a military town in Tuen Mun to defend the coastal area in the region.[45] The first village school, Li Ying College, was established around 1075 in the New Territories under the Northern Song Dynasty.[46] During the Mongol invasion in 1276, the Southern Song Dynasty court moved to Fujian, then to Lantau Island and later to Sung Wong Toi (modern Kowloon City), but the child Emperor Huaizong of Song committed suicide by drowning with his officials after being defeated in the Battle of Yamen. Hau Wong, an official of the emperor is still worshipped in Hong Kong today.[47]

The earliest recorded European visitor was Jorge Álvares, a Portuguese explorer who arrived in 1513.[48][49] After establishing settlements in the region, Portuguese merchants began trading in southern China. At the same time, they invaded and built up military fortifications in Tuen Mun. Military clashes between China and Portugal led to the expulsion of the Portuguese. In the mid-16th century, the Haijin order banned maritime activities and prevented contact with foreigners; it also restricted local sea activity.[47] In 1661–69, the territory was affected by the Great Clearance ordered by Kangxi Emperor, which required the evacuation of the coastal areas of Guangdong. It is recorded that about 16,000 persons from Xin'an County were driven inland, and 1,648 of those who left are said to have returned when the evacuation was rescinded in 1669.[50] What is now the territory of Hong Kong became largely wasteland during the ban.[51] In 1685, Kangxi became the first emperor to open limited trading with foreigners, which started with the Canton territory. He also imposed strict terms for trades such as requiring foreign traders to live in restricted areas, staying only for the trading seasons, banning firearms, and trading with silver only.[52] The East India Company made the first sea venture to China in 1699, and the region's trade with British merchants developed rapidly soon after. In 1711, the company established its first trading post in Canton. By 1773, the British reached a landmark 1,000 chests of opium in Canton with China consuming 2,000 chests annually by 1799.[52]

British colonial era

In 1839, the refusal by Qing Dynasty authorities to import opium resulted in the First Opium War between China and Britain. Hong Kong Island was occupied by British forces on 20 January 1841 and was initially ceded under the Convention of Chuenpee as part of a ceasefire agreement between Captain Charles Elliot and Governor Qishan, but the agreement was never ratified due to a dispute between high ranking officials in both governments.[53] It was not until 29 August 1842 that the island was formally ceded in perpetuity to the United Kingdom under the Treaty of Nanking. The British established a crown colony with the founding of Victoria City the following year.[54]

In 1860, after China's defeat in the Second Opium War, the Kowloon Peninsula and Stonecutter's Island were ceded in perpetuity to Britain under the Convention of Peking. In 1898, under the terms of the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory, Britain obtained a 99-year lease of Lantau Island and the adjacent northern lands, which became known as the New Territories.[55] Hong Kong's territory has remained unchanged to the present.[56][57] In 1894, the deadly Third Pandemic of bubonic plague spread from China to Hong Kong, causing 50,000–100,000 deaths.[58]

During the first half of the 20th century, Hong Kong was a free port, serving as an entrepôt of the British Empire. The British introduced an education system based on their own model, while the local Chinese population had little contact with the European community of wealthy tai-pans settled near Victoria Peak.[55]

In conjunction with its military campaign, the Empire of Japan invaded Hong Kong on 8 December 1941. The Battle of Hong Kong ended with British and Canadian defenders surrendering control of the colony to Japan on 25 December. During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, civilians suffered widespread food shortages, rationing, and hyper-inflation due to forced exchange of currency for military notes. Through a policy of enforced repatriation of the unemployed to the mainland throughout the period, because of the scarcity of food, the population of Hong Kong had dwindled from 1.6 million in 1941 to 600,000 in 1945, when the United Kingdom resumed control of the colony.[59]

Hong Kong's population recovered quickly as a wave of migrants from China arrived for refuge from the ongoing Chinese Civil War. When the PRC was proclaimed in 1949, more migrants fled to Hong Kong for fear of persecution by the Communist Party.[55] Many corporations in Shanghai and Guangzhou shifted their operations to Hong Kong.[55]

In the 1950s, Hong Kong's rapid industrialisation was driven by textile exports and other expanded manufacturing industries. As the population grew and labour costs remained low, living standards rose steadily.[60] The construction of Shek Kip Mei Estate in 1953 followed a massive slum fire, and marked the beginning of the public housing estate programme designed to cope with the huge influx of immigrants. Trade in Hong Kong accelerated even further when Shenzhen, immediately north of Hong Kong, became a special economic zone of the PRC, and Hong Kong was established as the main source of foreign investment in China.[61] The manufacturing competitiveness gradually declined in Hong Kong due to the development of the manufacturing industry in southern China beginning in the early 1980s. By contrast, the service industry in Hong Kong experienced high rates of growth in the 1980s and 1990s after absorbing workers released from the manufacturing industry.[62]

In 1983, when the United Kingdom reclassified Hong Kong from a British crown colony to a dependent territory, the governments of the United Kingdom and China were already discussing the issue of Hong Kong's sovereignty due to the impending expiry (within two decades) of the lease of the New Territories. In 1984, the Sino-British Joint Declaration – an agreement to transfer sovereignty to the People's Republic of China in 1997 – was signed.[55] It stipulated that Hong Kong would be governed as a special administrative region, retaining its laws and a high degree of autonomy for at least 50 years after the transfer. The Hong Kong Basic Law, which would serve as the constitutional document after the transfer, was ratified in 1990.[55]

Since 1997

On 1 July 1997, the transfer of sovereignty from United Kingdom to the PRC occurred, officially ending 156 years of British colonial rule. Hong Kong became China's first special administrative region, and Tung Chee Hwa took office as the first Chief Executive of Hong Kong. That same year, Hong Kong suffered an economic double blow from the Asian financial crisis and the H5N1 avian influenza.[55] In 2003, Hong Kong was gravely affected by the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).[63][64] The World Health Organization reported 1,755 infected and 299 deaths in Hong Kong.[65] An estimated 380 million Hong Kong dollars (US$48.9 million) in contracts were lost as a result of the epidemic.[66]

On 10 March 2005, Tung Chee Hwa announced his resignation as Chief Executive due to "health problems".[67] Donald Tsang, the Chief Secretary for Administration at the time, entered the 2005 election unopposed and became the second Chief Executive of Hong Kong on 21 June 2005.[68] In 2007, Tsang won the Chief Executive election and continued his second term in office.[69]

In 2009, Hong Kong hosted the fifth East Asian Games, in which nine national teams competed. It was the first and largest international multi-sport event ever held in the territory.[70] Today, Hong Kong continues to serve as an important global financial centre, but faces uncertainty over its future due to the growing mainland China economy, and its relationship with the PRC government in areas such as democratic reform and universal suffrage.[71]

Governance

In accordance with the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and the underlying principle of one country, two systems, Hong Kong has a "high degree of autonomy as a special administrative region in all areas except defence and foreign affairs."[note 4] The declaration stipulates that the region maintain its capitalist economic system and guarantees the rights and freedoms of its people for at least 50 years beyond the 1997 handover.[note 5] The guarantees over the territory's autonomy and the individual rights and freedoms are enshrined in a constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law, which outlines the system of governance of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, but which is subject to the interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC).[72][73]

The primary pillars of government are the Executive Council, the civil service, the Legislative Council, and the Judiciary. The Executive Council is headed by the Chief Executive who is elected by the Election Committee and then appointed by the Central People's Government.[74][75] The civil service is a politically neutral body that implements policies and provides government services, where public servants are appointed based on meritocracy.[24][76] The Legislative Council has 60 members, half of which are directly elected by universal suffrage by permanent residents of Hong Kong according to five geographical constituencies. The other half, known as functional constituencies, are directly elected by a smaller electorate, which consists of corporate bodies and persons from various stipulated functional sectors. The entire council is headed by the President of the Legislative Council who serves as the speaker.[77][78] Judges are appointed by the Chief Executive on the recommendation of an independent commission.[20][79]

The implementation of the Basic Law, including how and when the universal suffrage promised therein is to be achieved, has been a major issue of political debate since the transfer of sovereignty. In 2002, the government's proposed anti-subversion bill pursuant to Article 23 of the Basic Law, which required the enactment of laws prohibiting acts of treason and subversion against the Chinese government, was met with fierce opposition, and eventually shelved.[22][80][81] Debate between pro-Beijing groups, which tend to support the Executive branch, and the Pan-democracy camp characterises Hong Kong's political scene, with the latter supporting a faster pace of democratisation, and the principle of one man, one vote.[82]

In 2004, the government failed to gain pan-democrat support to pass its so-called "district council model" for political reform.[83] In 2009, the government reissued the proposals as the "Consultation Document on the Methods for Selecting the Chief Executive and for Forming the LegCo in 2012". The document proposed the enlargement of the Election Committee, Hong Kong's electoral college, from 800 members to 1,200 in 2012 and expansion of the legislature from 60 to 70 seats. The 10 new legislative seats would consist of five geographical constituency seats and five functional constituency seats, to be voted in by elected district council members from among themselves.[84] The proposals were destined for rejection by pan-democrats once again, but a significant breakthrough occurred after the Central People's Government accepted a counter-proposal by the Democratic Party. In particular, the Pan-democracy camp was split when the proposal to directly elect five newly created functional seats was not acceptable to two constituent parties. The Democratic Party sided with the government for the first time since the handover and passed the proposals with a vote of 46–12.[85]

Legal system and judiciary

Hong Kong's legal system is completely independent from the legal system of China. In contrast to mainland China's civil law system, Hong Kong continues to follow the English Common Law tradition established under British rule.[86] Hong Kong's courts may refer to decisions rendered by courts of other common law jurisdictions as precedents,[20][87] and judges from other common law jurisdictions are allowed to sit as non-permanent judges of the Court of Final Appeal.[20][87]

Structurally, the court system consists of the Court of Final Appeal, the High Court, which is made up of the Court of Appeal and the Court of First Instance, and the District Court, which includes the Family Court.[88] Other adjudicative bodies include the Lands Tribunal, the Magistrates' Courts, the Juvenile Court, the Coroner's Court, the Labour Tribunal, the Small Claims Tribunal, and the Obscene Articles Tribunal.[88] Justices of the Court of Final Appeal are appointed by Hong Kong's Chief Executive.[20][87]

The Department of Justice is responsible for handling legal matters for the government. Its responsibilities include providing legal advice, criminal prosecution, civil representation, legal and policy drafting and reform, and international legal cooperation between different jurisdictions.[86] Apart from prosecuting criminal cases, lawyers of the Department of Justice act on behalf of the government in all civil and administrative lawsuits against the government.[86] As protector of the public interest, the department may apply for judicial reviews and may intervene in any cases involving the greater public interest.[89] The Basic Law protects the Department of Justice from any interference by the government when exercising its control over criminal prosecution.[90][91]

Administrative districts

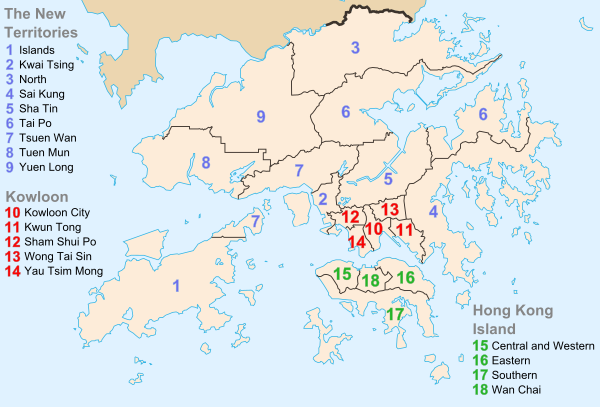

Hong Kong has a unitary system of government; no local government has existed since the two municipal councils were abolished in 2000. As such there is no formal definition for its cities and towns. Administratively, Hong Kong is subdivided into 18 geographic districts, each represented by a district council which advises the government on local matters such as public facilities, community programmes, cultural activities, and environmental improvements.[92]

There are a total of 534 district council seats, 405 of which are elected; the rest are appointed by the Chief Executive and 27 ex officio chairmen of rural committees.[92] The Home Affairs Department communicates government policies and plans to the public through the district offices.[93]

Military

When Hong Kong was a British colony and later, a dependent territory, defence was provided by the British military under the command of the Governor of Hong Kong who was ex officio Commander-in-chief.[94] When the PRC assumed sovereignty in 1997, the British barracks were replaced by a garrison of the People's Liberation Army, comprising ground, naval, and air forces, and under the command of the Chinese Central Military Commission.[14]

The Basic Law protects local civil affairs against interference by the garrison, and members of the garrison are subject to Hong Kong laws. The Hong Kong Government remains responsible for the maintenance of public order; however, it may ask the PRC government for help from the garrison in maintaining public order and in disaster relief. The PRC government is responsible for the costs of maintaining the garrison.[22][95]

Geography and climate

Template:Image stack Hong Kong is located on China's south coast, 60 km (37 mi) east of Macau on the opposite side of the Pearl River Delta. It is surrounded by the South China Sea on the east, south, and west, and borders the Guangdong city of Shenzhen to the north over the Shenzhen River. The territory's 1,104 km2 (426 sq mi) area consists of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, the New Territories, and over 200 offshore islands, of which the largest is Lantau Island. Of the total area, 1,054 km2 (407 sq mi) is land and 50 km2 (19 sq mi) is inland water. Hong Kong claims territorial waters to a distance of 3 nautical miles (5.6 km). Its land area makes Hong Kong the 179th largest inhabited territory in the world.[3][9]

As much of Hong Kong's terrain is hilly to mountainous with steep slopes, less than 25% of the territory's landmass is developed, and about 40% of the remaining land area is reserved as country parks and nature reserves.[96] Most of the territory's urban development exists on Kowloon peninsula, along the northern edge of Hong Kong Island, and in scattered settlements throughout the New Territories.[97] The highest elevation in the territory is at Tai Mo Shan, 957 metres (3,140 ft) above sea level.[98] Hong Kong's long and irregular coast provides it with many bays, rivers and beaches.[99]

Despite Hong Kong's reputation of being intensely urbanised, the territory has tried to promote a green environment,[100] and recent growing public concern has prompted the severe restriction of further land reclamation from Victoria Harbour.[101] Awareness of the environment is growing as Hong Kong suffers from increasing pollution compounded by its geography and tall buildings. Approximately 80% of the city's smog originates from other parts of the Pearl River Delta.[102]

Situated just south of the Tropic of Cancer, Hong Kong has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa). Summer is hot and humid with occasional showers and thunderstorms, and warm air coming from the southwest. Summer is when typhoons are most likely, sometimes resulting in flooding or landslides. Winter weather usually starts sunny and becomes cloudier towards February, with the occasional cold front bringing strong, cooling winds from the north. The most temperate seasons are spring, which can be changeable, and autumn, which is generally sunny and dry.[103] Hong Kong averages 1,948 hours of sunshine per year,[104] while the highest and lowest ever recorded temperatures at the Hong Kong Observatory are 36.1 °C (97.0 °F) and 0.0 °C (32.0 °F), respectively.[105]

Economy

Hong Kong was once described by Milton Friedman as the world’s greatest experiment in laissez-faire capitalism.[106] It maintains a highly developed capitalist economy, ranked the freest in the world by the Index of Economic Freedom for 15 consecutive years.[107][108][109] It is an important centre for international finance and trade, with one of the greatest concentrations of corporate headquarters in the Asia-Pacific region,[110] and is known as one of the Four Asian Tigers for its high growth rates and rapid development from the 1960s to the 1990s. Between 1961 and 1997 Hong Kong's gross domestic product grew 180 times while per-capita GDP increased 87 times over.[111][112][113]

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is the seventh largest in the world, with a market capitalisation of US$2.3 trillion as of December 2009.[114] In that year, Hong Kong raised 22 percent of worldwide initial public offering (IPO) capital, making it the largest centre of IPOs in the world.[115] Hong Kong's currency is the Hong Kong dollar, which has been pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1983.[116]

The Hong Kong Government has traditionally played a mostly passive role in the economy, with little by way of industrial policy and almost no import or export controls. Market forces and the private sector were allowed to determine practical development. Under the official policy of "positive non-interventionism", Hong Kong is often cited as an example of laissez-faire capitalism. Following the Second World War, Hong Kong industrialised rapidly as a manufacturing centre driven by exports, and then underwent a rapid transition to a service-based economy in the 1980s.[117]

Hong Kong matured to become a financial centre in the 1990s, but was greatly affected by the Asian financial crisis in 1998, and again in 2003 by the SARS outbreak. A revival of external and domestic demand has led to a strong recovery, as cost decreases strengthened the competitiveness of Hong Kong exports and a long deflationary period ended.[118][119] Government intervention, initiated by the later colonial governments and continued since 1997, has steadily increased, with the introduction of export credit guarantees, a compulsory pension scheme, a minimum wage, anti-discrimination laws, and a state mortgage backer.[106]

The territory has little arable land and few natural resources, so it imports most of its food and raw materials. Hong Kong is the world's eleventh largest trading entity,[120] with the total value of imports and exports exceeding its gross domestic product. It is the world's largest re-export centre.[121] Much of Hong Kong's exports consist of re-exports,[122] which are products made outside of the territory, especially in mainland China, and distributed via Hong Kong. Even before the transfer of sovereignty, Hong Kong had established extensive trade and investment ties with the mainland, which now enable it to serve as a point of entry for investment flowing into the mainland. At the end of 2007, there were 3.46 million people employed full-time, with the unemployment rate averaging 4.1% for the fourth straight year of decline.[123] Hong Kong's economy is dominated by the service sector, which accounts for over 90% of its GDP, while industry constitutes 9%. Inflation was at 2.5% in 2007.[124] Hong Kong's largest export markets are mainland China, the United States, and Japan.[3]

As of 2009, Hong Kong is the fifth most expensive city for expatriates, behind Tokyo, Osaka, Moscow, and Geneva. In 2008, Hong Kong was ranked sixth, and in 2007, it was ranked fifth.[125] In 2009, Hong Kong was ranked third in the Ease of Doing Business Index.[126]

Demographics

The territory's population is 7.03 million. In 2009, Hong Kong had a birth rate of 11.7 per 1,000 population and a fertility rate of 1,032 children per 1,000 women.[127] Residents from mainland China do not have the right of abode in Hong Kong, nor are they allowed to enter the territory freely.[80] However, the influx of immigrants from mainland China, approximating 45,000 per year, is a significant contributor to its population growth – a daily quota of 150 Mainland Chinese with family ties in Hong Kong are granted a "one way permit".[128] Life expectancy in Hong Kong is 79.16 years for males and 84.79 years for females as of 2009, making it one of the highest life expectancies in the world.[3]

About 95% of the people of Hong Kong are of Chinese descent,[11] the majority of whom are Taishanese, Chiu Chow, other Cantonese people, and Hakka. Hong Kong's Han majority originate mainly from the Guangzhou and Taishan regions in Guangdong province.[12] The remaining 5% of the population is composed of non-ethnic Chinese forming a highly visible group despite their smaller numbers.[11] There is a South Asian population of Indians, Pakistanis and Nepalese; some Vietnamese refugees have become permanent residents of Hong Kong. There are also Europeans (mostly British), Americans, Canadians, Japanese, and Koreans working in the city's commercial and financial sector.[note 6] In 2008, there were an estimate of 252,500 foreign domestic helpers from Indonesia and the Philippines working in Hong Kong.[130]

Hong Kong's de facto official language is Cantonese, a Chinese language originating from Guangdong province to the north of Hong Kong.[131] English is also an official language, and according to a 1996 by-census is spoken by 3.1 percent of the population as an everyday language and by 34.9 percent of the population as a second language.[132] Signs displaying both Chinese and English are common throughout the territory. Since the 1997 handover, an increase in immigrants from mainland China and greater integration with the mainland economy have brought an increasing number of Mandarin speakers to Hong Kong.[133]

Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of religious freedom, guaranteed by the Basic Law. Ninety percent of Hong Kong's population practises a mix of local religions,[3] most prominently Buddhism, but also, Confucianism, and Taoism.[134] A Christian community of around 600,000 forms about 8% of the total population;[135][136] it is nearly equally divided between Catholics and Protestants, although smaller Christian communities exist, including the Latter-Day Saints[137] and Jehovah's Witnesses.[138] The Anglican and Roman Catholic churches each freely appoint their own bishops, unlike in mainland China. There are also Sikh, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu and Bahá'í communities.[135] The practice of Falun Gong is tolerated.[139]

Statistically Hong Kong's income gap is the worst in Asia Pacific. According to a report by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme in 2008, Hong Kong's Gini coefficient, at 0.53, was the highest in Asia and "relatively high by international standards".[140][141] However, the government has stressed that income disparity does not equate to worsening of the poverty situation, and that the Gini coefficient is not strictly comparable between regions. The government has named economic restructuring, changes in household sizes, and the increase of high-income jobs as factors that have skewed the Gini coefficient.[142][143][144]

Education

Hong Kong's education system used to roughly follow the system in England,[17] although international systems exist. The government maintains a policy of "mother tongue instruction" (Chinese: 母語教學) in which the medium of instruction is Cantonese ,[145] with written Chinese and English. In secondary schools, 'biliterate and trilingual' proficiency is emphasised, and Mandarin-language education has been increasing.[146] The Programme for International Student Assessment ranked Hong Kong's education system as the second best in the world.[147] Hong Kong's public schools are operated by the Education Bureau. The system features a non-compulsory three-year kindergarten, followed by a compulsory six-year primary education, a three-year junior secondary education, a non-compulsory two-year senior secondary education leading to the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examinations and a two-year matriculation course leading to the Hong Kong Advanced Level Examinations.[148] The New Senior Secondary academic structure and curriculum was implemented in September 2009, which provides for all students to receive three years of compulsory junior and three years of compulsory senior secondary education.[18][149] Under the new curriculum, there is only public examination, namely the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education.[150]

Most comprehensive schools in Hong Kong fall under three categories: the rarer public schools; the more common subsidised schools, including government aids-and-grant schools; and private schools, often run by Christian organisations and having admissions based on academic merit rather than on financial resources. Outside this system are the schools under the Direct Subsidy Scheme and private international schools.[149]

There are nine public universities in Hong Kong, and a number of private higher institutions, offering various bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees, other higher diplomas, and associate degree courses.The University of Hong Kong, the oldest institution of tertiary education in the territory, was described by Quacquarelli Symonds as a "world-class comprehensive research university"[151] and was ranked 24th on the 2009 THES - QS World University Rankings,[152] making it first in Asia.[153] The Hong Kong University of Science & Technology was ranked 35th in the world in 2009 and ranked second in Asia for 2010. The Chinese University of Hong Kong was ranked 46th in the world in 2009 and ranked fourth in Asia for 2010.[153]

Culture

Hong Kong is frequently described as a place where "East meets West", reflecting the culture's mix of the territory's Chinese roots with influences from its time as a British colony.[16] Hong Kong balances a modernised way of life with traditional Chinese practices. Concepts like feng shui are taken very seriously, with expensive construction projects often hiring expert consultants, and are often believed to make or break a business.[154] Other objects like Ba gua mirrors are still regularly used to deflect evil spirits,[155] and buildings often lack any floor number that has a 4 in it,[156] due to its similarity to the word for "die" in Cantonese.[157] The fusion of east and west also characterises Hong Kong's cuisine, where dim sum, hot pot, and fast food restaurants coexist with haute cuisine.[158]

Hong Kong is a recognised global centre of trade, and calls itself an "entertainment hub".[159] Its martial arts film genre gained a high level of popularity in the late 1960s and 1970s. Several Hollywood performers, notable actors and martial artists have originated from Hong Kong cinema, notably Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Chow Yun-fat, Michelle Yeoh, Maggie Cheung and Jet Li. A number of Hong Kong film-makers have achieved widespread fame in Hollywood, such as John Woo, Wong Kar-wai, and Stephen Chow.[159] Homegrown films such as Chungking Express, Infernal Affairs, Shaolin Soccer, Rumble in the Bronx, and In the Mood for Love have gained international recognition. Hong Kong is the centre for Cantopop music, which draws its influence from other forms of Chinese music and Western genres, and has a multinational fanbase.[160]

The Hong Kong government supports cultural institutions such as the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. The government's Leisure and Cultural Services Department subsidises and sponsors international performers brought to Hong Kong. Many international cultural activities are organised by the government, consulates, and privately.[161][162]

Hong Kong has two licensed terrestrial broadcasters – ATV and TVB. There are three local and a number of foreign suppliers of cable and satellite services.[163] The production of Hong Kong's soap dramas, comedy series, and variety shows reach audiences throughout the Chinese-speaking world. Magazine and newspaper publishers in Hong Kong distribute and print in both Chinese and English, with a focus on sensationalism and celebrity gossip.[164] The media in Hong Kong is relatively free from official interference compared to mainland China, although the Far Eastern Economic Review points to signs of self-censorship by journals whose owners have close ties to or business interests in the People's Republic of China and states that even Western media outlets are not immune to growing Chinese economic power.[165]

Hong Kong offers wide recreational and competitive sport opportunities despite its limited land area. It sends delegates to international competitions such as the Olympic Games and Asian Games, and played host to the equestrian events during the 2008 Summer Olympics.[166] There are major multipurpose venues like Hong Kong Coliseum and MacPherson Stadium. Hong Kong's steep terrain and extensive trail network with expansive views attracts hikers, and its rugged coastline provides many beaches for swimming.[167]

Architecture

According to Emporis, there are 7,650 skyscrapers in Hong Kong, which puts the city at the top of world rankings.[168] The high density and tall skyline of Hong Kong's urban area is due to a lack of available sprawl space, with the average distance from the harbour front to the steep hills of Hong Kong Island at 1.3 km (0.81 mi),[169] much of it reclaimed land. This lack of space causes demand for dense, high-rise offices and housing. Thirty-six of the world's 100 tallest residential buildings are in Hong Kong.[170] More people in Hong Kong live or work above the 14th floor than anywhere else on Earth, making it the world's most vertical city.[27][28]

As a result of the lack of space and demand for construction, few older buildings remain, and the city is becoming a centre for modern architecture. The International Commerce Centre (ICC), at 484 m (1,588 ft) high, is the tallest building in Hong Kong and the third tallest in the world, by height to roof measurement. [171] The tallest building prior to the ICC is Two International Finance Centre, at 415 m (1,362 ft) high.[172] Other recognisable skyline features include the HSBC Headquarters Building, the triangular-topped Central Plaza with its pyramid-shaped spire, The Center with its night-time multi-coloured neon light show, and I. M. Pei's Bank of China Tower with its sharp, angular façade. According to the Emporis website, the city skyline has the biggest visual impact of all world cities.[173] The oldest remaining historic structures including the Tsim Sha Tsui Clock Tower, the Central Police Station, and the remains of Kowloon Walled City were constructed during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[174][175][176]

There are many development plans in place, including the construction of new government buildings,[177] waterfront redevelopment in Central,[178] and a series of projects in West Kowloon.[179] More high-rise development is set to take place on the other side of Victoria Harbour in Kowloon, as the 1998 closure of the nearby Kai Tak Airport lifted strict height restrictions.[180]

Transport

Hong Kong's transportation network is highly developed. Over 90% of daily travels (11 million) are on public transport,[29] the highest such percentage in the world.[30] Payment can be made using the Octopus card, a stored value system introduced by the Mass Transit Railway (MTR), which is widely accepted on railways, buses and ferries, and accepted like cash at other outlets.[181][182]

The city's main railway company was merged with the urban mass transit operator in 2007, creating a comprehensive rail network for the whole territory.[183] This rapid transit system has 150 stations, which serve 3.4 million people a day.[184] Hong Kong Tramways, which has served the territory since 1904, covers the northern parts of Hong Kong Island.[185]

Hong Kong's bus service is franchised and run by private operators. Five privately owned companies provide franchised bus service across the territory, together operating more than 700 routes. The two largest, Kowloon Motor Bus provides 402 routes in Kowloon and New Territories; Citybus operates 154 routes on Hong Kong Island; both run cross-harbour services. Double-decker buses were introduced to Hong Kong in 1949, and are now almost exclusively used; single-decker buses remain in use for routes with lower demand or roads with lower load capacity. Public light buses serve most parts of Hong Kong, particularly areas where standard bus lines cannot reach or do not reach as frequently, quickly, or directly.[186]

The Star Ferry service, founded in 1888, operates four lines across Victoria Harbour and provides scenic views of Hong Kong's skyline for its 53,000 daily passengers.[187] It acquired iconic status following its use as a setting on The World of Suzie Wong. Travel writer Ryan Levitt considered the main Tsim Sha Tsui to Central crossing one of the most picturesque in the world.[188] Other ferry services are provided by operators serving outlying islands, new towns, Macau, and cities in mainland China. Hong Kong is famous for its junks traversing the harbour, and small kai-to ferries that serve remote coastal settlements.[189][190]

Hong Kong Island's steep, hilly terrain was initially served by sedan chairs.[191] The Peak Tram, the first public transport system in Hong Kong, has provided vertical rail transport between Central and Victoria Peak since 1888.[192] In Central and Western district, there is an extensive system of escalators and moving pavements, including the longest outdoor covered escalator system in the world, the Mid-Levels escalator.[193]

Hong Kong International Airport is a leading air passenger gateway and logistics hub in Asia and one of the world's busiest airports in terms of international passenger and cargo movement, serving more than 47 million passengers and handling 3.74 million tonnes (4.12 million tons) of cargo in 2007.[194] It replaced the overcrowded Kai Tak Airport in Kowloon in 1998, and has been rated as the world's best airport in a number of surveys.[195] Over 85 airlines operate at the two-terminal airport and it is the primary hub of Cathay Pacific, Dragonair, Air Hong Kong, Hong Kong Airlines, and Hong Kong Express.[194][196]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ This is the official convention employed on the Chinese text of the Hong Kong regional emblem, the text of the Hong Kong Basic Law, and the Hong Kong Government website,[1] although "Hong Kong Special Administrative Region" and "Hong Kong" is also accepted.

- ^ The Basic Law of Hong Kong states that the official languages are "Chinese and English".[2] It does not explicitly specify the standard for "Chinese". While Standard Mandarin and Simplified Chinese characters are used as the spoken and written standards in mainland China, Cantonese and Traditional Chinese characters are the long-established de facto standards in Hong Kong. See also: Bilingualism in Hong Kong.

- ^ The name was often written as Hongkong until the government adopted the current form in 1926 (Hongkong Government Gazette, Notification 479, 3 September 1926). Nevertheless, some century-old organisations still use the name, such as the Hongkong Post, Hongkong Electric and The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. While the names of most cities in the People's Republic of China are romanised into English using Pinyin, the official English name is Hong Kong rather than the pinyin Xianggang.

- ^ Section 3(2) of the Sino-British Joint Declaration states in part, "The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region will enjoy a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs which, are the responsibilities of the Central People's Government."

- ^ Section 3(5) of the Sino-British Joint Declaration states that the social and economic systems and lifestyle in Hong Kong will remain unchanged, and mentions rights and freedoms ensured by law. Section 3(12) states in part, "The above-stated basic policies of the People's Republic of China ... will remain unchanged for 50 years."

- ^ The Census and Statistics Department has reported that the number of people identifying themselves as "white" fell from 46,584 in the 2001 census to 36,384 in the 2006 by-census, a decline of 22 percent.[129]

References

- ^ "GovHK: Residents". Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "Official Languages". Hong Kong Government. 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Hong Kong". The World Factbook. CIA. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Population and Vital Events". Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Population Density by Area" (PDF). Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Hong Kong". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2009 – Gini Index". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Geography and Climate, Hong Kong" (PDF). Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ Ash, Russell (2006). The Top 10 of Everything 2007. Hamlyn. p. 78. ISBN 0-600-61532-4.

- ^ a b c "Population by Ethnicity, 2001 and 2006". Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ a b Fan Shuh Ching (1974). "The Population of Hong Kong" (PDF). World Population Year. Committee for International Coordination of National Research in Demography: 18–20. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Joint Declaration of the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the Question of Hong Kong". Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, Hong Kong Government. 19 December 1984. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

The Government of the People's Republic of China declares that to recover the Hong Kong area (including Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories, hereinafter referred to as Hong Kong) is the common aspiration of the entire Chinese people, and that it has decided to resume the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong with effect from 1 July 1997.

- ^ a b "On This Day: 1997: Hong Kong handed over to Chinese control". BBC News. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "The World's Most Competitive Financial Centers". CNBC. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ^ a b "24 hours in Hong Kong: Urban thrills where East meets West". CNN. 8 March 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ a b Chan, Shun-hing; Leung, Beatrice (2003). Changing Church and State Relations in Hong Kong, 1950–2000. Hong Kong University Press. p. 24. ISBN 962-2096123.

- ^ a b "Programme Highlights". Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ So, Dudley L.; Lin, Nan; Poston (2001). The Chinese Triangle of Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 13–29. ISBN 0-313-30869-1.

- ^ a b c d e "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 4". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Russell, Peter H.; O'Brien, David M. (2001). Judicial Independence in the Age of Democracy: Critical Perspectives from around the World. University of Virginia Press. p. 306. ISBN 9780813920160.

- ^ a b c "Basic Law, Chapter II". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Ghai, Yash P. (2000). Autonomy and Ethnicity: Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-ethnic States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–97. ISBN 9780521786423.

- ^ a b "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 1". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Rioni, S. G. (2002). Hong Kong in Focus: Political and Economic Issues. Nova Publishers. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781590332375.

- ^ "Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in April 2007" (PDF). Triennial Central Bank Survey 2007. Bank for International Settlements: 7. September 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Vertical Cities: Hong Kong/New York". Time Out. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Home page". Skyscraper Museum. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Public Transport Introduction". Transport Department, Hong Kong Government. Archived from the original on 7 July 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ a b Lam, William H. K.; Bell, Michael G. H. (2003). Advanced Modeling for Transit Operations and Service Planning. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 231. ISBN 9780080442068.

- ^ a b Room, Adrian (2005). Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company. p. 168. ISBN 0786422483.

- ^ Bishop, Kevin; Roberts, Annabel (1997). China's Imperial Way. China Books and Periodicals. p. 218. ISBN 9622175112.

- ^ Fairbank, John King (1953). Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854 (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 123–128. ISBN 9780804706483.

- ^ "The Trial Excavation at the Archaeological Site of Wong Tei Tung, Sham Chung, Hong Kong SAR". Hong Kong Archaeological Society. January 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "港現舊石器制造場 嶺南或為我發源地". People's Daily (in Chinese). 17 February 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Tang, Chung (2005). "考古與香港尋根" (PDF). New Asia Monthly (in Chinese). 32 (6). New Asia College: 6–8. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Li, Hui (2002). "百越遗传结构的一元二分迹象" (PDF). Guangxi Ethnic Group Research (in Chinese). 70 (4): 26–31. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "2005 Field Archaeology on Sham Chung Site". Hong Kong Archaeological Society. January 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Declared Monuments in Hong Kong – New Territories". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Characteristic Culture". Invest Nanhai. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Ban Biao; Ban Gu; Ban Zhao. "地理志". Book of Han (in Chinese). Vol. Volume 28. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help) - ^ Peng, Quanmin (2001). "从考古材料看汉代深港社会". Relics From South (in Chinese). Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Keat, Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 932. ISBN 1576077705.

- ^ "Archaeological Background". Hong Kong Yearbook. 21. Hong Kong Government. 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Siu Kwok-kin. "唐代及五代時期屯門在軍事及中外交通上的重要性". From Sui to Ming (in Chinese). Education Bureau, Hong Kong Government: 40–45. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Sweeting, Anthony (1990). Education in Hong Kong, Pre-1841 to 1941: Fact and Opinion. Hong Kong University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9622092586.

- ^ a b Barber, Nicola (2004). Hong Kong. Gareth Stevens. p. 48. ISBN 9780836851984.

- ^ Porter, Jonathan (1996). Macau, the Imaginary City: Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present. Westview Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780813328362.

- ^ Edmonds, Richard L. (2002). China and Europe Since 1978: A European Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521524032.

- ^ Hayes, James (1974). "The Hong Kong Region: Its Place in Traditional Chinese Historiography and Principal Events Since the Establishment of Hsin-an County in 1573" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 14: 108–135. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong Museum of History: "The Hong Kong Story" Exhibition Materials" (PDF). Hong Kong Museum of History. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ a b Discovery Channel guide. Insight Guide Hong Kong. American Psychological Association Publications. 2005 [1980]. p. 18. ISBN 9812582460.

- ^ Courtauld, Caroline; Holdsworth, May; Vickers, Simon (1997). The Hong Kong Story. Oxford University Press. pp. 38–58. ISBN 9780195903539.

- ^ Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 9780700711451.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wiltshire, Trea (1997). Old Hong Kong. Vol. Volume II: 1901–1945 (5th ed.). FormAsia Books. p. 148. ISBN 9627283134.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "History of Hong Kong". Global Times. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Scott, Ian (1989). Political change and the crisis of legitimacy in Hong Kong. University of Hawaii Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780824812690.

- ^ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 499. ISBN 0313341028.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bradsher, Keith (17 April 2005). "Thousands March in Anti-Japan Protest in Hong Kong". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Moore, Lynden (1985). The growth and structure of international trade since the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780521469791.

- ^ Wei, Shang-Jin (2000). "Why Does China Attract So Little Foreign Direct Investment?" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 6–8. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dodsworth, John; Mihaljek, Dubravko (1997). International Monetary Fund. p. 54. ISBN 1557756724.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Links between SARS, human genes discovered". People's Daily. 16 January 2004. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ Lee, S. H. (2006). SARS in China and Hong Kong. Nova Publishers. pp. 63–70. ISBN 9781594546785.

- ^ "Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003". World Health Organization. 31 December 2003. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ "疫情衝擊香港經濟損失巨大" (in Chinese). BBC News. 28 May 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Yau, Cannix (11 March 2005). "Tung's gone. What next?". The Standard. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Appointment of Chief Executive". GN(E). Hong Kong Government. 21 June 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Donald Tsang wins Chief Executive election". Hong Kong Government. 25 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Chinese Taipei Wins God Medal in Men's 400-Meter Relay". Kuomintang. 14 December 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit (2 January 2008). "Hong Kong politics: China sets reform timetable". The Economist. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "Basic Law, Chapter VIII". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Chen, Wenmin; Fu, H. L.; Ghai, Yash P. (2000). Hong Kong's Constitutional Debate: Conflict Over Interpretation. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 235–236. ISBN 9789622095090.

- ^ "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 6". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ "Civil Service" (PDF). Information Services Department, Hong Kong Government. June 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ Burns, John P. (2004). Government Capacity and the Hong Kong Civil Service. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 9780195905977.

- ^ "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 3". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Madden, Frederick (2000). The End of Empire: Dependencies since 1948. Pt. 1: The West Indies, British Honduras, Hong Kong, Fiji, Cyprus, Gibralter, and the Falklands. Vol. Volume VIII: Select Documents on the Constitutional History of the British Empire and Commonwealth. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 188–196. ISBN 9780313290725.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Gaylord, Mark S.; Gittings, Danny; Traver, Harold (2009). Introduction to Crime, Law and Justice in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9789622099784.

- ^ a b "Right of Abode in HKSAR—Verification of Eligibility for Permanent Identity Card". Immigration Department, Hong Kong Government. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Presentation to Legislative Council on Right of Abode Issue". Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor. 10 May 1999. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Warren I.; Li, Zhao (1997). Hong Kong Under Chinese Rule: The Economic and Political Implications of Reversion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 220–235. ISBN 9780521627610.

- ^ Ming, Sing (2006). "The Legitimacy Problem and Democratic Reform in Hong Kong". Journal of Contemporary China. 15 (48). Informa: 517–532. doi:10.1080/10670560600736558.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Public Consultation on the Methods for Selecting the Chief Executive and for Forming the Legislative Council in 2012" (PDF). Hong Kong Government. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ Balfour, Frederik; Lui, Marco (25 June 2010). "Hong Kong Lawmakers Approve Tsang's Election Plan". Businessweek. Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Legal System in Hong Kong". Department of Justice, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ a b c Ash, Robert F. (2003). Hong Kong in Transition: One Country, Two Systems. Vol. Volume 11: RoutledgeCurzon Studies in the Modern History of Asia. Psychology Press. pp. 161–188. ISBN 9780415299541.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Introduction". Hong Kong Judiciary. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ "About Us: Organisation chart of the Secretary for Justice's Office". Department of Justice, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- ^ "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 2". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Weisenhaus, Doreen; Cottrell, Jill; Yan, Mei Ning (2007). Hong Kong Media Law: A Guide for Journalists and Media Professionals. Hong Kong University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9789622098084.

- ^ a b "Hong Kong – The Facts: District Administration" (PDF). Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ "Mission". Home Affairs Department, Hong Kong Government. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Huque, Ahmed Shafiqul; Lee, Grace O. M.; Cheung, Anthony (1998). The Civil Service in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9622094589.

- ^ Rioni, S. G. (2002). Hong Kong in Focus: Political and Economic Issues. Nova Publishers. pp. 154–163. ISBN 9781590332375.

- ^ Morton, Brian; Harper, Elizabeth. An Introduction to the Cape d'Aguilar Marine Reserve, Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9789622093881.

{{cite book}}: Text "year-1995" ignored (help) - ^ "2006 Population By-census" (PDF). Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ "Tai Mo Shan Country Park". Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, Hong Kong Government. 17 March 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Hong Kong". Olympic Council of Asia. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "Chief Executive pledges a clean, green, world-class city". Hong Kong Trade Development Council. 2001. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "HK harbour reclamation reprieve". BBC News. 9 January 2004. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (5 November 2006). "Dirty Air Becomes Divisive Issue in Hong Kong Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Climate of Hong Kong". Hong Kong Observatory. 4 May 2003. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ "Hong Kong in Figures 2008 Edition". Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. 27 February 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Extreme Values and Dates of Occurrence of Extremes of Meteorological Elements between 1884–1939 and 1947–2006 for Hong Kong". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ a b "End of an experiment". The Economist. 15 July 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "2009 Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ "2008 Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Top 10 Countries". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ Bromma, Hubert (2007). How to Invest in Offshore Real Estate and Pay Little Or No Taxes. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 161. ISBN 9780071470094.

- ^ Preston, Peter Wallace; Haacke, Jürgen (2003). Contemporary China: The Dynamics of Change at the Start of the New Millennium. Psychology Press. pp. 80–107. ISBN 9780700716371.

- ^ Yeung, Rikkie (2008). Moving Millions: The Commercial Success and Political Controvesies of Hong Kong's Railways. Hong Kong University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9789622099630.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 1 Executive Summary" (PDF). City of London. 2007. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "World Federation of Exchanges – Statistics/Monthly". World Federation of Exchanges. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong IPOs May Raise Record $48 Billion in 2010, E&Y Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ Hong Kong's Linked Exchange Rate System (PDF). Hong Kong Monetary Authority. p. 33. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Tsang, Donald (18 September 2006). "Big Market, Small Government" (Press release). Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong's Export Outlook for 2008: Maintaining Competitiveness through Supply Chain Management". Hong Kong Trade Development Council. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "HKDF – Has Hong Kong Lost its Competitiveness?". Hong Kong Democratic Foundation. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "About Hong Kong". Hong Kong Government. 2006. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Panama Canal: A plan to unlock prosperity". The Economist. 3 December 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ Dhungana, Gita (29 December 2006). "Growth in exports defies predictions". The Standard. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics, Hong Kong Government, March 2008

- ^ Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific 2009: Addressing Triple Threats to Development. United Nations Publications. 2009. pp. 94–99. ISBN 9789211205770.

- ^ "Worldwide Cost of Living survey 2009". Mercer. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Explore Economies". World Bank. 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong: The Facts – Population" (PDF). Hong Kong Government. 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Who is entitled to sponsor family members to come to live in Hong Kong? If I am a lawful resident of Hong Kong, can my family members in the Mainland (or elsewhere) apply to immigrate to Hong Kong?". Community Legal Information Centre. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Counting Expat Numbers a Complex Task (Hong Kong)". Global Auto Industry. July 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ International Labour Office (2009). Application of International Labour Standards 2009 (I). International Labour Organization. p. 640. ISBN 9221206343.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Westra, Nick (5 June 2007). "Hong Kong as a Cantonese speaking city". Journalism and Media Studies Centre, University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "ICE Hong Kong". University College London. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ Yum, Cherry (2007). "Which Chinese? Dialect Choice in Philadelphia's Chinatown" (PDF). Haverford College. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Chapter 18: Religion and Custom". Hong Kong Yearbook. Hong Kong Government. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ a b "International Religious Freedom Report 2007 – Hong Kong". United States Department of State. 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ "Hong Kong Year Book (2006):Chapter 18 – Religion and Custom: Christianity". Hong Kong Government. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ "Hong Kong China Temple". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ "2007 Report of Jehovah's Witnesses Worldwide". The Watchtower. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2006 – Hong Kong". United States Department of State. 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Piboontanasawat, Nipa (23 October 2008). "Hong Kong Has Highest Income Disparity in Asia, UN Report Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "State of the World's Cities 2008/2009" (PDF) (Press release). United Nations Human Settlements Programme. 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Subcommittee to Study the Subject of Combating Poverty" (PDF). Legislative Council of Hong Kong. 23 June 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Policies in Assisting Low-income Employees" (PDF). Commission on Poverty. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. 23 January 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Kwok Kwok-chuen (12 February 2007). "Income Distribution of Hong Kong and the Gini Coefficient" (PDF). Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ "母語教學小冊子" (in Chinese). Education Bureau, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Policy for Secondary Schools -Medium of Instruction Policy for Secondary Schools". Education Bureau, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "PISA 2006 Science Competencies for Tomorrow's World". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ "Kindergarten, Primary and Secondary Education". Education Bureau, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ a b Li, Arthur (18 May 2005). "Creating a better education system". Hong Kong Government. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "HKDSE". Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings™ Launches 2010 Research". Quacquarelli Symonds. 8 March 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings 2009 – Top 200 world universities". Times Higher Education Supplement. Quacquarelli Symonds. 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Top 200 Universities". Quacquarelli Symonds. 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ "Feng shui used in 90% of RP businesses". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 17 February 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Fowler, Jeaneane D.; Fowler, Merv (2008). Chinese Religions: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781845191726.

- ^ Xi, Xu; Ingham, Mike (2003). City Voices: Hong Kong writing in English, 1945–present. Hong Kong University Press. p. 181. ISBN 9789622096059.

- ^ Chan, Cecilia; Chow, Amy (2006). Death, Dying and Bereavement: a Hong Kong Chinese Experience. Vol. Volume 1. Hong Kong University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9789622097872.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Stone, Andrew; Chow, Chung Wah; Ho, Reggie (15 January 2008). Hong Kong and Macau. Lonely Planet. p. 7. ISBN 9781741046656.

- ^ a b "Hong Kong calls itself Asia's entertainment hub". Monsters and Critics. 23 March 2007.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (24 September 2001). "Hong Kong music circles the globe with its easy-listening hits and stars". Time. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "General Information". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "About the Museum". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Broadcasting: Licences". Commerce and Economic Development Bureau, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Li, Jinquan (2002). Global Media Spectacle: News War Over Hong Kong. State University of New York Press. pp. 69–74. ISBN 9780791454725.

- ^ Walker, Christopher; Cook, Sarah (12 October 2009). "China's Export of Censorship". Far Eastern Economic Review. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Hong Kong Olympic Equestrian Venue (Beas River & Shatin)". Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Macdonald, Phil (2006). National Geographic Traveler: Hong Kong (2nd ed.). National Geographic Society. p. 263. ISBN 9780792253693.

- ^ "Most Active Cities in terms of High-rise Construction". Emporis. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ Tong, C. O.; Wong, S. C. (1997). "The advantages of a high density, mixed land use, linear urban development". Transportation. 24 (3): 295–307. doi:10.1023/A:1004987422746.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "World's Tallest Residential Towers". Emporis. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "International Commerce Centre". Emporis. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ "Two International Finance Centre". Emporis. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Emporis Skyline Ranking". Emporis. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Declared Monuments in Hong Kong – Hong Kong Island". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Declared Monuments in Hong Kong – Kowloon Island". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Sinn, Elizabeth (1990). "Kowloon Walled City: Its Origin and Early History" (PDF). Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 27: 30–31. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Tamar Development Project". Hong Kong Government. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Central Waterfront Design Competition". Designing Hong Kong. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ^ "West Kowloon Cultural District Public Engagement Exercise". Home Affairs Bureau, Hong Kong Government. 26 August 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "Kai Tak building height restrictions lifted". Hong Kong Government. 10 July 1998. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ^ "Octopus Card Information". Octopus Cards Limited. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ Poon, Simpson; Chau, Patrick (February 2001). "Octopus: The Growing E-payment System in Hong Kong". Electronic Markets. 11 (2). Informa: 97–106. doi:10.1080/101967801300197016.

- ^ "Press Release: Government has reached understanding with MTRCL on the terms for merging the MTR and KCR systems". Hong Kong Government. 11 April 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ^ "Tourist Information". Mass Transit Railway. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ^ "The Company". Hong Kong Tramways. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ^ Cullinane, S. (January 2002). "The relationship between car ownership and public transport provision: a case study of Hong Kong". Physics Letters B. 9 (1). Elsevier Science Limited: 290. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.10.071.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Ng, Tze-wei (10 November 2006). "Not even HK's storied Star Ferry can face down developers". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ "Ferry is amongst the world's best". BBC News. 19 October 2004. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Liam. "Hong Kong: 10 Things to Do in 24 Hours". Time. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Cushman, Jennifer Wayne (1993). Fields from the sea: Chinese junk trade with Siam during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. SEAP Publications. p. 57. ISBN 0877277117.

- ^ Thomson, John (1873). Illustrations of China and Its People. Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle. p. 96.

- ^ Cavaliero, Eric (24 July 1997). "Grand old lady to turn 110". The Standard. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Gold, Anne (6 July 2001). "Hong Kong's Mile-Long Escalator System Elevates the Senses : A Stairway to Urban Heaven". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b "About Us". Hong Kong International Airport. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "International travellers have voted Hong Kong the best airport in the world". Skytrax. 8 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "Air Cargo and Aviation Logistic Services" (PDF). Hong Kong International Airport. p. 1. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

Further reading

- Endacott, G. B (1964). An Eastern Entrepot;: A Collection of Documents Illustrating the History of Hong Kong. Her Majesty's Stationary Office. p. 293. ASIN B0007J07G6.

- Fu, Poshek; Deser, David (2002). The Cinema of Hong Kong: History, Arts, Identity. Cambridge University Press. p. 346. ISBN 9780521776028.

- Lui, Adam Yuen-chung (1990). Forts and Pirates – A History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong History Society. p. 114. ISBN 9627489018.

- Liu, Shuyong; Wang, Wenjiong; Chang, Mingyu (1997). An Outline History of Hong Kong. Foreign Languages Press. p. 291. ISBN 9787119019468.

- Ngo, Tak-Wing (1 August 1999). Hong Kong's History: State and Society Under Colonial Rule. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 9780415208680.

- Tsang, Steve (1995). Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 312. ISBN 9622093922.

- Tsang, Steve (4 September 2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845114190.

- Welsh, Frank (1993). A Borrowed place: the history of Hong Kong. Kodansha International. p. 624. ISBN 9781568360027.

External links

- Government

- Discover Hong Kong – Official site of the Hong Kong Tourism Board

- Other

- Hong Kong at Encyclopædia Britannica

- HongKong at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

Wikimedia Atlas of Hong Kong

Wikimedia Atlas of Hong Kong- Template:Wikitravel

- WikiSatellite view of Hong Kong at WikiMapia

Template:Sino-Tibetan-speaking

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Hong Kong templates

- Use dmy dates from September 2010

- 1997 establishments

- Chinese-speaking countries and territories

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Former British colonies

- Hong Kong

- Independent cities

- Metropolitan areas of China

- Pearl River Delta

- Populated coastal places in Hong Kong

- Populated places established in 1842

- Port cities and towns in China

- South China Sea

- Special administrative regions of the People's Republic of China