HIV/AIDS

| HIV/AIDS | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (or acronym AIDS or Aids), is a collection of symptoms and infections resulting from the specific damage to the immune system caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[1] It results from the latter stages of advanced HIV infection in humans, thereby leaving compromised individuals prone to opportunistic infections and tumors. Although treatments for both AIDS and HIV exist to slow the virus' progression in a human patient, there is no known cure.

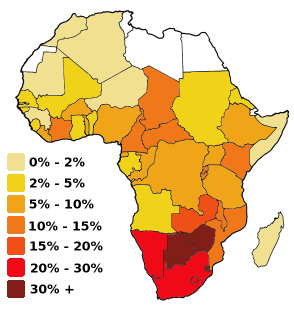

Most researchers believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa [2] during the twentieth century; it is now a global epidemic. UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognized on December 1, 1981, making it one of the most destructive pandemics in recorded history. In 2005 alone, AIDS claimed between an estimated 2.8 and 3.6 million, of which more than 570,000 were children.[3] In countries where there is access to antiretroviral treatment, both mortality and morbidity of HIV infection have been reduced [4]. However, side-effects of these antiretrovirals have also caused problems such as lipodystrophy, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance and an increase in cardiovascular risks [5]. The difficulty of consistently taking the medicines has also contributed to the rise of viral escape and resistance to the medicines [6].

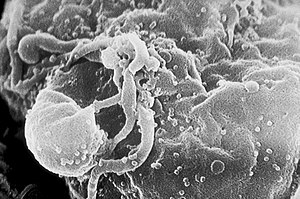

Infection by HIV

AIDS is the most severe manifestation of infection with HIV. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects vital components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It also directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells. As CD4+ T cells are required for the proper functioning of the immune system, when enough CD4+ cells have been destroyed by HIV, the immune system barely works, leading to AIDS. Acute HIV infection progresses over time to clinical latent HIV infection and then to early symptomatic HIV infection and later, to AIDS, which is identified on the basis of the amount of CD4 positive cells in the blood and the presence of certain infections.

In the absence of antiretroviral therapy, progression from HIV infection to AIDS occurs at a median of between nine to ten years and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months [7]. However, the rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals, from two weeks up to 20 years. Many factors affect the rate of progression. These include factors that influence the body's ability to defend against HIV, including the infected person's genetic inheritance, general immune function [8][9], access to health care, age and other coexisting infections [7][10][11]. Different strains of HIV [12][13] may also cause different rates of clinical disease progression.

Diagnosis

AIDS and HIV case definitions

Since 1981, many different definitions have been developed for epidemiological surveillance such as the Bangui definition and the 1994 expanded World Health Organization AIDS case definition. However, these were never intended to be used for clinical staging of patients, for which they are neither sensitive nor specific. The World Health Organizations (WHO) staging system for HIV infection and disease, using clinical and laboratory data, can be used in developing countries and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Classification System can be used in developed nations.

WHO Disease Staging System for HIV Infection and Disease

In 1990, the World Health Organization (WHO) grouped these infections and conditions together by introducing a staging system for patients infected with HIV-1 [14]. This was updated in September 2005. Most of these conditions are opportunistic infections that can be easily treated in healthy people.

- Stage I: HIV disease is asymptomatic and not categorized as AIDS

- Stage II: include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections

- Stage III: includes unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than a month, severe bacterial infections and pulmonary tuberculosis or

- Stage IV includes toxoplasmosis of the brain, candidiasis of the esophagus, trachea, bronchi or lungs and Kaposi's sarcoma; these diseases are used as indicators of AIDS.

CDC Classification System for HIV Infection

In the USA, the definition of AIDS is governed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 1993, the CDC expanded their definition of AIDS to include healthy HIV positive people with a CD4 positive T cell count of less than 200 per µl of blood. The majority of new AIDS cases in the United States are reported on the basis of a low T cell count in the presence of HIV infection [15]

HIV test

Approximately half of those infected with HIV don't know that they are infected until they are diagnosed with AIDS. HIV test kits are used to screen donor blood and blood products, and to diagnose HIV in individuals. Typical HIV tests, including the HIV enzyme immunoassay and the Western blot assay, detect HIV antibodies in serum, plasma, oral fluid, dried blood spot or urine of patients. Other tests to look for HIV antigens, HIV-RNA, and HIV-DNA are also commercially available and can be used to detect HIV infection prior to the development of detectable antibodies. However, these assays are not specifically approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the diagnosis of HIV infection.

Symptoms and Complications

The symptoms of AIDS are primarily the result of conditions that do not normally develop in individuals with healthy immune systems. Most of these conditions are infections caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites that are normally controlled by the elements of the immune system that HIV damages. Opportunistic infections are common in people with AIDS [16]. Nearly every organ system is affected. People with AIDS also have an increased risk of developing various cancers such as Kaposi sarcoma, cervical cancer and cancers of the immune system known as lymphomas.

Additionally, people with AIDS often have systemic symptoms of infection like fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen glands, chills, weakness, and weight loss [17][18]. After the diagnosis of AIDS is made, the current average survival time with antiretroviral therapy is estimated to be between 4 to 5 years [19], but because new treatments continue to be developed and because HIV continues to evolve resistance to treatments, estimates of survival time are likely to continue to change. Without antiretroviral therapy, progression to death normally occurs within a year [7]. Most patients die from opportunistic infections or malignancies associated with the progressive failure of the immune system [20].

The rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals and has been shown to be affected by many factors such as host susceptibility [8][9][21], health care and co-infections [7][20], and peculiarities of the viral strain [13][22][23]. Also, the specific opportunistic infections that AIDS patients develop depends in part on the prevalence of these infections in the geographic area in which the patient lives.

The major pulmonary illnesses

- Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia: Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (originally known as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, often abbreviated PCP) is relatively rare in normal, immunocompetent people but common among HIV-infected individuals. Before the advent of effective treatment and diagnosis in Western countries it was a common immediate cause of death. In developing countries, it is still one of the first indications of AIDS in untested individuals, although it does not generally occur unless the CD4 count is less than 200 per µl [24].

- Tuberculosis: Among infections associated with HIV, tuberculosis (TB) is unique in that it may be transmitted to immunocompetent persons via the respiratory route, is easily treatable once identified, may occur in early-stage HIV disease, and is preventable with drug therapy. However, multi-drug resistance is a potentially serious problem. Even though its incidence has declined because of the use of directly observed therapy and other improved practices in Western countries, this is not the case in developing countries where HIV is most prevalent. In early-stage HIV infection (CD4 count >300 cells per µl), TB typically presents as a pulmonary disease. In advanced HIV infection, TB may present atypically and extrapulmonary TB is common infecting bone marrow, bone, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, liver, regional lymph nodes, and the central nervous system [25].

The major gastro-intestinal illnesses

- Esophagitis: Esophagitis is an inflammation of the lining of the lower end of the esophagus (gullet or swallowing tube leading to the stomach). In HIV infected individuals, this could be due to fungus (candidiasis), virus (herpes simplex-1 or cytomegalovirus). In rare cases, it could be due to mycobacteria [26].

- Unexplained chronic diarrhea: In HIV infection, there are many possible causes of diarrhea, including common bacterial (Salmonella, Shigella, Listeria, Campylobacter, or Escherichia coli) and parasitic infections, and uncommon opportunistic infections such as cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis. Diarrhea may follow a course of antibiotics (common for Clostridium difficile). It may also be a side effect of several drugs used to treat HIV, or it may simply accompany HIV infection, particularly during primary HIV infection. In the later stages of HIV infection, diarrhea is thought to be a reflection of changes in the way the intestinal tract absorbs nutrients, and may be an important component of HIV-related wasting [27].

The major neurological illnesses

- Toxoplasmosis: Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by the single-celled parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. T. gondii usually infects the brain causing toxoplasma encephalitis. It can also infect and cause disease in the eyes and lungs [28].

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a demyelinating disease, in which the myelin sheath covering the axons of nerve cells is gradually destroyed, impairing the transmission of nerve impulses. It is caused by a virus called JC virus which occurs in 70% of the population in latent form, causing disease only when the immune system has been severly weakened, as is the case for AIDS patients. It progresses rapidly, usually causing death within months of diagnosis [29].

- HIV-associated dementia: HIV-1 associated dementia (HAD) is a metabolic encephalopathy induced by HIV infection and fueled by immune activation of brain macrophages and microglia [30]. These cells are actively infected with HIV and secrete neurotoxins of both host and viral origin. Specific neurologic impairments are manifested by cognitive, behavioral, and motor abnormalities that occur after years of HIV infection and is associated with low CD4+ T cell levels and high plasma viral loads. Prevalence is between 10-20% in Western countries [31] and has only been seen in 1-2% of India based infections [32][33].

- Cryptococcal meningitis This infection of the meninges (the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord) by the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans can cause fevers, headache, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Patients may also develop seizures and confusion. If untreated, it can be lethal.

The major HIV-associated malignancies

Patients with HIV infection have substantially increased incidence of several malignancies [34][35]. Several of these, Kaposi's sarcoma, high-grade lymphoma, and cervical cancer confer a diagnosis of AIDS when they occur in an HIV-infected person.

- Kaposi's sarcoma: Kaposi's sarcoma is the most common tumor in HIV-infected patients. The appearance of this tumor in young gay men in 1981 was one of the first signals of the AIDS epidemic. It is caused by a gammaherpesvirus called Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV). It often appears as purplish nodules on the skin, but other organs, especially the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs can be affected.

- High-grade lymphoma: Several high-grade B cell lymphomas have substantially increased incidence in HIV-infected patients and often portend a poor prognosis. The most common AIDS-defining lymphomas are Burkitt's lymphoma, Burkitt's-like lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), including primary central nervous system lymphoma. Primary effusion lymphoma is less common. Many of these lymphomas are caused by either Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or KSHV.

- Cervical cancer: Cervical cancer in HIV-infected women is also considered AIDS-defining. It is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Other tumors: In addition to the AIDS-defining tumors listed above, HIV-infected patients are also at increased risk of certain other tumors, such as Hodgkin's disease and anal and rectal carcinomas. However, the incidence of many common tumors, such as breast cancer or colon cancer, are not increased in HIV-infected patients. Most AIDS-associated malignancies are caused by co-infection of patients with an oncogenic DNA virus, especially Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and human papillomavirus (HPV). In areas where HAART is extensively used to treat AIDS, the incidence of many AIDS-related malignancies has decreased, but at the same time malignancies overall have become the most common cause of death of HIV-infected patients [36].

Other opportunistic infections

Patients with AIDS and severe immunosuppression often develop opportunistic infections that present with non-specific symptoms, especially low grade fevers and weight loss. These include infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare and cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV can also cause colitis, as described above, and CMV retinitis can cause blindness. Penicilliosis due to Penicillium marneffei is now the third most common opportunistic infection (after extrapulmonary tuberculosis and cryptococcosis) in HIV-positive individuals within the endemic area of Southeast Asia [37].

Transmission

Since the beginning of the epidemic, three main transmission routes of HIV have been identified:

- Sexual route. The majority of HIV infections have been, and still are, acquired through unprotected sexual relations. Sexual transmission occurs when there is contact between sexual secretions of one partner with the rectal, genital or mouth mucous membranes of another.

- Blood or blood product route. This transmission route is particularly important for intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs and recipients of blood transfusions and blood products. Health care workers (nurses, laboratory workers, doctors etc) are also concerned, although more rarely. Also concerned by this route are people who give and receive tattoos and piercings.

- Mother-to-child route (vertical transmission). The transmission of the virus from the mother to the child can occur in utero during the last weeks of pregnancy and at childbirth. Breast feeding also presents a risk of infection for the baby. In the absence of treatment, the transmission rate between the mother and child was 20%. However, where treatment is available, combined with the availability of Cesarian section, this has been reduced to 1%.

HIV has been found in the saliva, tears and urine of infected individuals, but due to the low concentration of virus in these biological liquids, the risk is considered to be negligible.

Prevention

The diverse transmission routes of HIV are well-known and established. Also well-known is how to prevent transmission of HIV. However, recent epidemiological and behavioral studies in Europe and North America have suggested that a substantial minority of young people continue to engage in high-risk practices and that despite HIV/AIDS knowledge, young people underestimate their own risk of becoming infected with HIV [38]. However, transmission of HIV between intravenous drug users has clearly decreased, and HIV transmission by blood transfusion has become quite rare in developed countries.

Prevention of sexual transmission of HIV

Underlying science

- Unprotected receptive sexual acts are at more risk than unprotected insertive sexual acts, with the risk for transmitting HIV from an infected partner to an uninfected partner through unprotected insertive anal intercourse greater than the risk for transmission through vaginal intercourse or oral sex. According to the French Ministry for Health, the probability of transmission per act varies from 0.03% (meaning 3 in ten thousand) to 0.07% for the case of receptive vaginal sex, from 0.02 to 0.05% in the case of insertive vaginal sex, from 0.01% to 0.185% in the case of insertive anal sex, and 0.5% to 3% in the case of receptive anal sex [39].

- Sexually-transmitted infections (STI) increase the risk of HIV transmission and infection because they cause the disruption of the normal epithelial barrier by genital ulceration and/or microulceration; and by accumulation of pools of HIV-susceptible or HIV-infected cells (lymphocytes and macrophages) in semen and vaginal secretions. Epidemiological studies from sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and North America have suggested that there is approximately a four times greater risk of becoming HIV-infected in the presence of a genital ulcer such as caused by syphilis and/or chancroid; and a significant though lesser increased risk in the presence of STIs such as gonorrhoea, chlamydial infection and trichomoniasis which cause local accumulations of lymphocytes and macrophages [40].

- Transmission of HIV depends on the infectiousness of the index case and the susceptibility of the uninfected partner. Infectivity seems to vary during the course of illness and is not constant between individuals. An undetectable plasma viral load does not mean that you have a low viral load in the seminal liquid or genital secretions. Each 10 fold increment of seminal HIV RNA is associated with an 81% increased rate of HIV transmission [40][41].

- People who are infected with HIV can still be infected by other, more virulent strains.

- Oral sex is not without its risks as it has been established that HIV can be transmitted through both insertive and receptive oral sex [42].

- Women are more susceptible to HIV-1 due to hormonal changes, vaginal microbial ecology and physiology, and a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases [43][44].

Prevention strategies

During a sexual act, only condoms, be they male or female, can reduce the chances of infection with HIV and other STIs and the chances of becoming pregnant. They must be used during all penetrative sexual intercourse with a partner who is HIV positive or whose status is unknown [45]. The effective use of condoms and screening of blood transfusion in North America, Western and Central Europe is credited with the low rates of AIDS in these regions.

Promoting condom use, however, has often proved controversial and difficult. Many religious groups, most visibly the Roman Catholic Church, have opposed the use of condoms on religious grounds, and have sometimes seen condom promotion as an affront to the promotion of marriage, monogamy and sexual morality. Other religious groups have argued that preventing HIV infection is a moral task in itself and that condoms are therefore acceptable or even praiseworthy from a religious point of view.

- The male latex condom is the single most efficient available technology to reduce the sexual transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. In order to be effective, they must be used correctly during each sexual act. Lubricants containing oil, such as petroleum jelly, or butter, must not be used as they weaken latex condoms and make them porous. If necessary, lubricants made from water are recommended. However, it is not recommended to use a lubricant for fellatio. Also, condoms have standards and expiration dates. It is essential to check the expiration date and if it conforms to European (EC 600) or American (D3492) standards before use.

- The female condom is an alternative to the male condom and is made from polyurethane, which allows it to be used in the presence of oil-based lubricants. They are larger than male condoms and have a stiffened ring-shaped opening, and are designed to be inserted into the vagina. The female condom also contains an inner ring which keeps the condom in place inside the vagina - inserting the female condom requires squeezing this ring.

With consistent and correct use of condoms, there is a very low risk of HIV infection. Studies on couples where one partner is infected show that with consistent condom use, HIV infection rates for the uninfected partner are below 1% per year [46].

Governmental programs

The U.S. government and U.S. health organizations both endorse the ABC Approach to lower the risk of acquiring AIDS during sex:

- Abstinence or delay of sexual activity, especially for youth,

- Being faithful, especially for those in committed relationships,

- Condom use, for those who engage in risky behavior.

This approach has been very successful in Uganda, where HIV prevalence has decreased from 15% to 5%. However, the ABC approach is far from all that Uganda has done, as "Uganda has pioneered approaches towards reducing stigma, bringing discussion of sexual behavior out into the open, involving HIV-infected people in public education, persuading individuals and couples to be tested and counseled, improving the status of women, involving religious organizations, enlisting traditional healers, and much more." (Edward Green, Harvard medical anthropologist). Also, it must be noted that there is no conclusive proof that abstinence-only programs have been successful in any country in the world in reducing HIV transmission. This is why condom use is heavily co-promoted. There is also considerable overlap with the CNN Approach. This is:

- Condom use, for those who engage in risky behavior.

- Needles, use clean ones

- Negotiating skills; negotiating safer sex with a partner and empowering women to make smart choices

The ABC approach has been criticized, because a faithful partner of an unfaithful partner is at risk of AIDS [47]. Many think that the combination of the CNN approach with the ABC approach will be the optimum prevention platform.

Circumcision

Current research is clarifying the relationship between male circumcision and HIV in differing social and cultural contexts. UNAIDS believes that it is premature to recommend male circumcision services as part of HIV prevention programmes [48]. Moreover, South African medical experts are concerned that the repeated use of unsterilised blades in the ritual circumcision of adolescent boys may be spreading HIV [49].

Prevention of blood or blood product route of HIV transmission

Underlying science

- Sharing and reusing syringes contaminated with HIV-infected blood represents a major risk for infection with not only HIV but also hepatitis B and hepatitis C. In the United States a third of all new HIV infections can be traced to needle sharing and almost 50% of long-term addicts have hepatitis C.

- The risk of being infected with HIV from a single prick with a needle that has been used on an HIV infected person though is thought to be about 1 in 150 (see table above). Post-exposure prophylaxis with anti-HIV drugs can further reduce that small risk [50].

- Universal precautions are frequently not followed in both sub-Saharan Africa and much of Asia because of both a shortage of supplies and inadequate training. The WHO estimates that approximately 2.5% of all HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa are transmitted through unsafe healthcare injections [51]. Because of this, the United Nations General Assembly, supported by universal medical opinion on the matter, has urged the nations of the world to implement universal precautions to prevent HIV transmission in health care settings [52].

Prevention strategies

- In those countries where improved donor selection and antibody tests have been introduced, the risk of transmitting HIV infection to blood transfusion recipients is extremely low. But according to the WHO, the overwhelming majority of the world's population does not have access to safe blood and "between 5% and 10% of HIV infections worldwide are transmitted through the transfusion of infected blood and blood products" [53].

- Medical workers who follow universal precautions or body substance isolation such as wearing latex gloves when giving injections and washing the hands frequently can help prevent infection of HIV.

- All AIDS-prevention organizations advise drug-users not to share needles and other material required to prepare and take drugs (including syringes, cotton balls, the spoons, water for diluting the drug, straws, crack pipes etc). It is important that people use new or properly sterilized needles for each injection. Information on cleaning needles using bleach is available from health care and addiction professionals and from needle exchanges. In the United States and some other countries, clean needles are available free in some cities, at needle exchanges or safe injection sites. Additionally, many states within the United States and some other nations have decriminalized needle possession and made it possible to buy injection equipment from pharmacists without a prescription.

Mother to child transmission

Underlying science

- There is a 15–30% risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child during pregnancy, labour and delivery [54]. In developed countries the risk can of transmission of HIV from mother to child can be as low as 0-5%. A number of factors influence the risk of infection, particularly the viral load of the mother at birth (the higher the load, the higher the risk). Breastfeeding increases the risk of transmission by 10–15%. This risk depends on clinical factors and may vary according to the pattern and duration of breastfeeding.

Prevention strategies

- Studies have shown that antiretroviral drugs, cesarean delivery and formula feeding reduce the chance of transmission of HIV from mother to child [55].

- When replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe, HIV-infected mothers are recommended to avoid breast feeding their infant. Otherwise, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life and should be discontinued as soon as possible [3].

Treatment

There is currently no cure for HIV or AIDS. Infection with HIV usually leads to AIDS and ultimately death. However, in western countries, most patients survive many years following diagnosis because of the availability of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)[19]. In the absence of HAART, progression from HIV infection to AIDS occurs at a median of between nine to ten years and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months[7]. HAART dramatically increases the time from diagnosis to death, and treatment research continues.

Current optimal HAART options consist of combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of anti-retroviral agents. Typical regimens consist of two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). This treatment is frequently referred to as HAART (highly-active anti-retroviral therapy) [56]. Anti-retroviral treatments, along with medications intended to prevent AIDS-related opportunistic infections, have played a part in delaying complications associated with AIDS, reducing the symptoms of HIV infection, and extending patients' life spans. Over the past decade the success of these treatments in prolonging and improving the quality of life for people with AIDS has improved dramatically [57][58].

Because HIV disease progression in children is more rapid than in adults, and laboratory parameters are less predictive of risk for disease progression, particularly for young infants, treatment recommendations from the DHHS have been more aggressive in children than in adults, the current guidelines were published November 3 2005 [59].

The DHHS also recommends that doctors should assess the viral load, rapidity in CD4 decline, and patient readiness while deciding when to recommend initiating treatment [60].

There are several concerns about antiretroviral regimens. The drugs can have serious side effects[61]. Regimens can be complicated, requiring patients to take several pills at various times during the day, although treatment regimens have been greatly simplified in recent years. If patients miss doses, drug resistance can develop [62]. Also, anti-retroviral drugs are costly, and the majority of the world's infected individuals do not have access to medications and treatments for HIV and AIDS.

Research to improve current treatments includes decreasing side effects of current drugs, further simplifying drug regimens to improve adherence, and determining the best sequence of regimens to manage drug resistance.

A number of studies have shown that measures to prevent opportunistic infections can be beneficial when treating patients with HIV infection or AIDS. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for patients who are not infected with these viruses and are at risk of getting infected. In addition, AIDS patients should receive vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae and should receive yearly vaccination against influenza virus. Patients with substantial immunosuppression are generally advised to receive prophylactic therapy for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP), and many patients may benefit from prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and Cryptococcus meningitis.

Alternative medicine

Ever since AIDS entered the public consciousness, various forms of alternative medicine have been used to try to treat symptoms or to try to affect the course of the disease itself. In the first decade of the epidemic when no useful conventional treatment was available, a large number of people with AIDS experimented with alternative therapies. The definition of "alternative therapies" in AIDS has changed since that time. During that time, the phrase often referred to community-driven treatments, not being tested by government or pharmaceutical company research, that some hoped would directly suppress the virus or stimulate immunity against it. These kinds of approaches have become less common over time as AIDS drugs have become more effective.

The phrase then and now also refers to other approaches that people hoped would improve their symptoms or their quality of life--for instance, massage, herbal and flower remedies and acupuncture; when used with conventional treatment, many now refer to these as "complementary" approaches. None of these treatments have been proven in controlled trials to have any effect in treating HIV or AIDS directly. However, some may improve feelings of well-being in people who believe in their value. Additionally, people with AIDS, like people with other illnesses such as cancer, also sometimes use marijuana to treat pain, combat nausea and stimulate appetite.

Epidemiology

UNAIDS and the WHO estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognized in 1981, making it one of the most destructive epidemics in recorded history. Despite recent, improved access to antiretroviral treatment and care in many regions of the world, the AIDS epidemic claimed an estimated 3.1 million (between 2.8 and 3.6 million) lives in 2005 of which more than half a million (570,000) were children [3].

Globally, between 36.7 and 45.3 million people are currently living with HIV [3]. In 2005, between 4.3 and 6.6 million people were newly infected and between 2.8 and 3.6 million people with AIDS died, an increase from 2004 and the highest number since 1981.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains by far the worst-affected region, with an estimated 23.8 to 28.9 million people currently living with HIV. More than 60% of all people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa, as are more than three quarters (76%) of all women living with HIV [3]. South & South East Asia are second most affected with 15%. AIDS accounts for the deaths of 500,000 children.

The latest evaluation report of the World Bank's Operations Evaluation Department assesses the development effectiveness of the World Bank's country-level HIV/AIDS assistance defined as policy dialogue, analytic work, and lending with the explicit objective of reducing the scope or impact of the AIDS epidemic [63]. This is the first comprehensive evaluation of the World Bank's HIV/AIDS support to countries, from the beginning of the epidemic through mid-2004. Because the Bank's assistance is for implementation of government programs by government, it provides important insights on how national AIDS programs can be made more effective.

The development of HAART as effective therapy for HIV infection and AIDS has substantially reduced the death rate from this disease in those areas where it is widely available. This has created the misperception that the disease has gone away. In fact, as the life expectancy of persons with AIDS has increased in countries where HAART is widely used, the number of persons living with AIDS has increased substantially. In the United States, for example, the number of persons with AIDS increased from about 35,000 in 1988 to over 220,000 in 1996 [64].

Origin of HIV/AIDS

The official date for the beginning of the AIDS epidemic is marked as June 18, 1981, when the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported a cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (now classified as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia) in five gay men in Los Angeles [65]. Originally dubbed GRID, or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, health authorities soon realized that nearly half of the people identified with the syndrome were not gay. In 1982, the CDC introduced the term AIDS to describe the newly recognized syndrome.

Three of the earliest known instances of HIV infection are as follows:

- A plasma sample taken in 1959 from an adult male living in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo [66].

- HIV found in tissue samples from an American teenager who died in St. Louis in 1969.

- HIV found in tissue samples from a Norwegian sailor who died around 1976.

Two species of HIV infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is more virulent and more easily transmitted. HIV-1 is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world, while HIV-2 is less easily transmitted and is largely confined to West Africa [67]. Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are of primate origin. The origin of HIV-1 is the Central Common Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes troglodytes). The origin of HIV-2 has been established to be the Sooty Mangabey (Cercocebus atys), an Old World monkey of Guinea Bissau, Gabon, and Cameroon.

One currently controversial possibility for the origin of HIV/AIDS was discussed in a 1992 Rolling Stone magazine article by freelance journalist Tom Curtis. He put forward the theory that AIDS was inadvertantly caused in the late 1950's in the Belgian Congo by Hilary Koprowski's research into a polio vaccine [68]. Although subsequently retracted due to libel issues surrounding its claims, the Rolling Stone article encouraged another freelance journalist, Edward Hooper, to travel to Africa for 7 years of research into this subject. Hooper's research resulted in his publishing a 1999 book, The River, in which he alleged that an experimental oral polio vaccine prepared using chimpanzee kidney tissue was the route through which SIV mutated into HIV and started the human AIDS epidemic, some time between 1957 to 1959 [69].

Alternative theories

A minority of scientists and activists question the connection between HIV and AIDS, or the existence of HIV, or the validity of current testing methods. These claims are met with resistance by, and often evoke frustration and hostility from, most of the scientific community, who accuse the dissidents of ignoring evidence in favor of HIV's role in AIDS, and irresponsibly posing a dangerous threat to public health by their continued activities. Dissidents assert that the current mainstream approach to AIDS, based on HIV causation, has resulted in inaccurate diagnoses, psychological terror, toxic treatments, and a squandering of public funds. The debate and controversy regarding this issue from the early 1980s to the present has provoked heated emotions and passions from both sides.

References

- ^ Marx, J. L. (1982). "New disease baffles medical community". Science. 217 (4560): 618–621. PMID 7089584.

- ^ Gao, F., Bailes, E., Robertson, D. L., Chen, Y., Rodenburg, C. M., Michael, S. F., Cummins, L. B., Arthur, L. O., Peeters, M., Shaw, G. M., Sharp, P. M. and Hahn, B. H. (1999). "Origin of HIV-1 in the Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes". Nature. 397 (6718): 436–441. PMID 9989410.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e UNAIDS (2006-01-17). "AIDS epidemic update, 2005" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "UNAIDS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Palella, F. J. Jr, Delaney, K. M., Moorman, A. C., Loveless, M. O., Fuhrer, J., Satten, G. A., Aschman and D. J., Holmberg, S. D. (1998). "Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (13): 853–860. PMID 9516219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montessori, V., Press, N., Harris, M., Akagi, L., Montaner, J. S. (2004). "Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection". CMAJ. 170 (2): 229–238. PMID 14734438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Becker, S., Dezii, C. M., Burtcel, B., Kawabata, H. and Hodder, S. (2002). "Young HIV-infected adults are at greater risk for medication nonadherence". MedGenMed. 4 (3): 21. PMID 12466764.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Morgan, D., Mahe, C., Mayanja, B., Okongo, J. M., Lubega, R. and Whitworth, J. A. (2002). "HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries?". AIDS. 16 (4): 597–632. PMID 11873003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Morgan2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Clerici, M., Balotta, C., Meroni, L., Ferrario, E., Riva, C., Trabattoni, D., Ridolfo, A., Villa, M., Shearer, G.M., Moroni, M. and Galli, M. (1996). "Type 1 cytokine production and low prevalence of viral isolation correlate with long-term non progression in HIV infection". AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 12 (11): 1053–1061. PMID 8827221.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Clerici" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Tang, J. and Kaslow, R. A. (2003). "The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". AIDS. 17 (Suppl 4): S51 – S60. PMID 15080180.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Morgan" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Gendelman, H. E., Phelps, W., Feigenbaum, L., Ostrove, J. M., Adachi, A., Howley, P. M., Khoury, G., Ginsberg, H. S. and Martin, M. A. (1986). "Transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat sequences by DNA viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83 (24): 9759–9763. PMID 2432602.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bentwich, Z., Kalinkovich., A. and Weisman, Z. (1995). "Immune activation is a dominant factor in the pathogenesis of African AIDS". Immunol. Today. 16 (4): 187–191. PMID 7734046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quiñones-Mateu, M. E., Mas, A., Lain de Lera, T., Soriano, V., Alcami, J., Lederman, M. M. and Domingo, E. (1998). "LTR and tat variability of HIV-1 isolates from patients with divergent rates of disease progression". Virus Research. 57 (1): 11–20. PMID 9833881.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Campbell, G. R., Pasquier, E., Watkins, J., Bourgarel-Rey, V., Peyrot, V., Esquieu, D., Barbier, P., de Mareuil, J., Braguer, D., Kaleebu, P., Yirrell, D. L. and Loret E. P. (2004). "The glutamine-rich region of the HIV-1 Tat protein is involved in T-cell apoptosis". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (46): 48197–48204. PMID 15331610.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Campbell" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ World Health Organisation (1990). "Interim proposal for a WHO staging system for HIV infection and disease". WHO Wkly Epidem. Rec. 65 (29): 221–228. PMID 1974812.

- ^ CDC (2006-02-09). "1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults". CDC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Holmes, C. B., Losina, E., Walensky, R. P., Yazdanpanah, Y., Freedberg, K. A. (2003). "Review of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in sub-Saharan Africa". Clin. Infect. Dis. 36 (5): 656–662. PMID 12594648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guss, D. A. (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 1". J. Emerg. Med. 12 (3): 375–384. PMID 8040596.

- ^ Guss, D. A. (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 2". J. Emerg. Med. 12 (4): 491–497. PMID 7963396.

- ^ a b Schneider, M. F., Gange, S. J., Williams, C. M., Anastos, K., Greenblatt, R. M., Kingsley, L., Detels, R., and Munoz, A. (2005). "Patterns of the hazard of death after AIDS through the evolution of antiretroviral therapy: 1984-2004". AIDS. 19 (17): 2009–2018. PMID 16260908.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Schneider" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Lawn, S. D. (2004). "AIDS in Africa: the impact of coinfections on the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection". J. Infect. Dis. 48 (1): 1–12. PMID 14667787. Cite error: The named reference "Lawn" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Tang, J. and Kaslow, R. A. (2003). "The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". AIDS. 17 (Suppl 4): S51 – S60. PMID 15080180.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campbell, G. R., Watkins, J. D., Esquieu, D., Pasquier, E., Loret, E. P. and Spector, S. A. (2005). "The C terminus of HIV-1 Tat modulates the extent of CD178-mediated apoptosis of T cells". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (46): 38376–39382. PMID 16155003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Senkaali, D., Muwonge, R., Morgan, D., Yirrell, D., Whitworth, J. and Kaleebu, P. (2005). "The relationship between HIV type 1 disease progression and V3 serotype in a rural Ugandan cohort". AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 20 (9): 932–937. PMID 15585080.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feldman, C. (2005). "Pneumonia associated with HIV infection". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18 (2): 165–170. PMID 15735422.

- ^ Decker, C. F. and Lazarus, A. (2000). "Tuberculosis and HIV infection. How to safely treat both disorders concurrently". Postgrad Med. 108 (2): 57–60, 65–68. PMID 10951746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zaidi, S. A. and Cervia, J. S. (2002). "Diagnosis and management of infectious esophagitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection". J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care (Chic Ill). 1 (2): 53–62. PMID 12942677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guerrant, R. L., Hughes, J. M., Lima, N. L., Crane, J. (1990). "Diarrhea in developed and developing countries: magnitude, special settings, and etiologies". Rev. Infect. Dis. 12 (Suppl 1): S41 – S50. PMID 2406855.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Luft, B. J. and Chua, A. (2000). "Central Nervous System Toxoplasmosis in HIV Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapy". Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2 (4): 358–362. PMID 11095878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sadler, M. and Nelson, M. R. (1997). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in HIV". Int. J. STD AIDS. 8 (6): 351–357. PMID 9179644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gray, F., Adle-Biassette, H., Chrétien, F., Lorin de la Grandmaison, G., Force, G., Keohane, C. (2001). "Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pathogenesis of HIV-induced lesions of the brain, correlations with HIV-associated disorders and modifications according to treatments". Clin. Neuropathol. 20 (4): 146–155. PMID 11495003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grant, I., Sacktor, H., and McArthur, J. (2005). "HIV neurocognitive disorders". In H. E. Gendelman, I. Grant, I. Everall, S. A. Lipton, and S. Swindells. (ed.) (ed.). The Neurology of AIDS (2nd ed.). London, U.K.: Oxford University Press. pp. 357–373. ISBN 0198526105.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Satishchandra, P., Nalini, A., Gourie-Devi, M., Khanna, N., Santosh, V., Ravi, V., Desai, A., Chandramuki, A., Jayakumar, P. N., and Shankar, S. K. (2000). "Profile of neurologic disorders associated with HIV/AIDS from Bangalore, south India (1989-96)". Indian J. Med. Res. 11: 14–23. PMID 10793489.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wadia, R. S., Pujari, S. N., Kothari, S., Udhar, M., Kulkarni, S., Bhagat, S., and Nanivadekar, A. (2001). "Neurological manifestations of HIV disease". J. Assoc. Physicians India. 49: 343–348. PMID 11291974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boshoff, C. and Weiss, R. (2002). "AIDS-related malignancies". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2 (5): 373–382. PMID 12044013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yarchoan, R., Tosatom G. and Littlem R. F. (2005). "Therapy insight: AIDS-related malignancies - the influence of antiviral therapy on pathogenesis and management". Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2 (8): 406–415. PMID 16130937.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bonnet, F., Lewden, C., May, T., Heripret, L., Jougla, E., Bevilacqua, S., Costagliola, D., Salmon, D., Chene, G. and Morlat, P. (2004). "Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". Cancer. 101 (2): 317–324. PMID 15241829.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Skoulidis, F., Morgan, M. S., and MacLeod, K. M. (2004). "Penicillium marneffei: a pathogen on our doorstep?". J. R. Soc. Med. 97 (2): 394–396. PMID 15286196.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dias, S. F., Matos, M. G. and Goncalves, A. C. (2005). "Preventing HIV transmission in adolescents: an analysis of the Portuguese data from the Health Behaviour School-aged Children study and focus groups". Eur. J. Public Health. 15 (3): 300–304. PMID 15941747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ French Ministry in charge of Health (2006-02-09). "Accidents d'exposition au risque de transmission du VIH" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|publishyear=(help) - ^ a b Laga, M., Nzila, N., Goeman, J. (1991). "The interrelationship of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: implications for the control of both epidemics in Africa". AIDS. 5 (Suppl 1): S55 – S63. PMID 1669925.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tovanabutra, S., Robison, V., Wongtrakul, J., Sennum, S., Suriyanon, V., Kingkeow, D., Kawichai, S., Tanan, P., Duerr, A. and Nelson, K. E. (2002). "Male viral load and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 subtype E in northern Thailand". J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 29 (3): 275–283. PMID 11873077.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rothenberg, R. B., Scarlett, M., del Rio, C., Reznik, D. and O'Daniels, C. (1998). "Oral transmission of HIV". AIDS. 12 (16): 2095–2105. PMID 9833850.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sagar, M., Lavreys, L., Baeten, J. M., Richardson, B. A., Mandaliya, K., Ndinya-Achola, J. O., Kreiss, J. K., and Overbaugh, J. (2004). "Identification of modifiable factors that affect the genetic diversity of the transmitted HIV-1 population". AIDS. 18 (4): 615–619. PMID 15090766.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lavreys, L., Baeten, J. M., Martin, H. L. Jr., Overbaugh, J., Mandaliya, K., Ndinya-Achola, J., and Kreiss, J. K. (2004). "Hormonal contraception and risk of HIV-1 acquisition: results of a 10-year prospective study". AIDS. 18 (4): 695–697. PMID 15090778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cayley, W. E. Jr. (2004). "Effectiveness of condoms in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV". Am. Fam. Physician. 70 (7): 1268–1269. PMID 15508535.

- ^ WHO (2006-01-17). "Condom Facts and Figures".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ The Economist (2006-01-17). "Too much morality, too little sense".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ WHO (2006-01-17). "UNAIDS statement on South African trial findings regarding male circumcision and HIV".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Various (2006-01-17). "Repeated Use of Unsterilized Blades in Ritual Circumcision Might Contribute to HIV Spread in S. Africa, Doctors Say". Kaisernetwork.org.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Fan, H., Conner, R. F. and Villarreal, L. P. eds, ed. (2005). AIDS: science and society (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 076370086X.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ WHO (2006-01-17). "WHO, UNAIDS Reaffirm HIV as a Sexually Transmitted Disease".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Africa Nation (2006-01-17). "Africa: Unsafe Health Care Spreading HIV".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ WHO (2006-01-17). "Blood safety....for too few".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Orendi, J. M., Boer, K., van Loon, A. M., Borleffs, J. C., van Oppen, A. C., Boucher, C. A. (1998). "Vertical HIV-I-transmission. I. Risk and prevention in pregnancy". Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 142 (50): 2720–2724. PMID 10065235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sperling, R. S., Shapirom D. E., Coombsm R. W., Todd, J. A., Herman, S. A., McSherry, G. D., O'Sullivan, M. J., Van Dyke, R. B., Jimenez, E., Rouzioux, C., Flynn, P. M. and Sullivan, J. L. (1996). "Maternal viral load, zidovudine treatment, and the risk of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from mother to infant". N. Engl. J. Med. 335 (22): 1621–1629. PMID 8965861.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Department of Health and Human Services (2006-01-17). "A Pocket Guide to Adult HIV/AIDS Treatment January 2005 edition".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Wood, E., Hogg, R. S., Yip, B., Harrigan, P. R., O'Shaughnessy, M. V. and Montaner, J. S. (2003). "Is there a baseline CD4 cell count that precludes a survival response to modern antiretroviral therapy?". AIDS. 17 (5): 711–720. PMID 12646794.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chene, G., Sterne, J. A., May, M., Costagliola, D., Ledergerber, B., Phillips, A. N., Dabis, F., Lundgren, J., D'Arminio Monforte, A., de Wolf, F., Hogg, R., Reiss, P., Justice, A., Leport, C., Staszewski, S., Gill, J., Fatkenheuer, G., Egger, M. E. and the Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. (2003). "Prognostic importance of initial response in HIV-1 infected patients starting potent antiretroviral therapy: analysis of prospective studies". Lancet. 362 (9385): 679–686. PMID 12957089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Department of Health and Human Services Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children (2006-01-17). "Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection (2006-01-17). "Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Saitoh, A., Hull, A. D., Franklin, P. and Spector, S. A. (2005). "Myelomeningocele in an infant with intrauterine exposure to efavirenz". J. Perinatol. 25 (8): 555–556. PMID 16047034.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dybul, M., Fauci, A. S., Bartlett, J. G., Kaplan, J. E., Pau, A. K.; Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV. (2002). "Guidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescents". Ann. Intern. Med. 137 (5 Pt 2): 381–433. PMID 12617573.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Bank (2006-01-17). "Evaluating the World Bank's Assistance for Fighting the HIV/AIDS Epidemic".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ CDC (1996). "U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 1996" (PDF). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 8 (2): 1–40.

- ^ CDC (2006-01-17). "Pneumocystis Pneumonia --- Los Angeles". CDC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - ^ Zhu, T., Korber, B. T., Nahmias, A. J., Hooper, E., Sharp, P. M. and Ho, D. D. (1998). "An African HIV-1 Sequence from 1959 and Implications for the Origin of the Epidemic". Nature. 391 (6667): 594–597. PMID 9468138.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reeves, J. D. and Doms, R. W (2002). "Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 6): 1253–1265. PMID 12029140.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Curtis, T. (1992). "The origin of AIDS". Rolling Stone (626): 54–59, 61, 106, 108.

- ^ Hooper, E. (1999). The River : A Journey to the Source of HIV and AIDS (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co. pp. 1–1070. ISBN 0316372617.

External links

- UNAIDS The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- Eldis HIV and AIDS - latest research and other resources on HIV and AIDS in developing countries

- International AIDS Society - the world's leading independent association of HIV/AIDS professionals

- AEGiS.org AIDS Education Global Information System

- World AIDS Day World AIDS Day 1 December - Show your support

- AIDS Assistance Evaluating the World Bank's Assistance for Fighting the HIV/AIDS Epidemic

- AIDS.ORG: Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Information

- AIDSinfo 2002 The Glossary of HIV/AIDS-Related Terms 4th Edition

- AIDSmeds.com: Comprehensive lessons on HIV/AIDS and their treatments

- US Center for Disease Control (2005) Divisions of HIV/AIDS Prevention

- FightAIDS@Home Distributed computing project against AIDS

- Health Action AIDS (2003) HIV Transmission in the Medical Setting

- NIAID/NIH 2003 Basic Information About AIDS and HIV

- NIAID/NIH 2003 Evidence That HIV causes AIDS

- NIAID/NIH 2004 How HIV Causes AIDS

- NIH 2001 History of AIDS Research in the NIH

- The Body 2005 The Body: The Complete HIV/AIDS Resource

- Origin of Aids Video Watch Free online : Origin of Aids Video

- Journal Watch 2005 AIDS Clinical Care

- UNAIDS Scenarios to 2025 Document regarding three scenarios for HIV/AIDS in Africa for the year 2025 (Large PDF file)

- AIDS dissident websites AIDS Wiki's comprehensive list of dissident websites

- The Body's list of resources criticizing the "AIDS reappraisal" movement The Body: AIDS Denialism

- Gestalt Therapy and AIDS Treatment Issues with AIDS Patients (1993)

AIDS News

- Nov 2005 - Progress in HIV vaccine research -- Recorded interview with Prof. Robert Gallo (HIV discoverer)