James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831– September 19, 1881) served as the 20th President of the United States, from March 4, 1881 until his assassination on September 19, 1881.[1] He survived a brief 200 days in office, the second shortest presidential tenure to that of William Henry Harrison. He was the only incumbent of the U.S. House of Representatives to be elected President.[2]

James Garfield was born in Moreland Hills, Ohio and in 1856 graduated from Williams College, Massachusetts. He married Lucretia Rudolph in 1858, and in 1860 was admitted to the Bar while serving as an Ohio State Senator (1859–1861). Garfield served as a major general in the United States Army during the American Civil War and fought at the Battle of Shiloh. He was elected to Congress as a Republican in 1863, opposing slavery and secession. When the leading GOP presidential contenders – Ulysses S. Grant, James G. Blaine and John Sherman – failed to garner the requisite support, Garfield became the party's compromise nominee for the 1880 Presidential Election and successfully defeated Democrat Winfield Hancock.[3] In his inaugural address, Garfield proposed substantial civil service reform which was eventually passed by his successor, Chester A. Arthur, in 1883 as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. His presidency was cut short when he was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau on July 2, 1881 while entering a railroad station in Washington D.C.. Garfield was the second United States President to be assassinated. As a consequence of Garfield's brief tenure in office, accomplishments were few. Following his death, he was succeeded by Vice-President Chester A. Arthur.[3]

Childhood

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831 in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio.[4] His father, Abram Garfield, of large stature and locally renowned as a wrestler,[5] died in 1833,[6] when James Abram was 17 months old.[7] Of Welsh ancestry, he was brought up and cared for by his mother, Eliza Ballou, who said, "he was the largest babe I had and looked like a red Irishman."[8] Garfield's parents joined Disciples of Christ Church, which later profoundly influenced their son.[9]

Garfield attended a predecessor of the Orange City Schools In Orange Township.[4] At age 16 he struck out on his own, drawn seaward as a mariner, and landed a job for six weeks as a canal driver near Cleveland;[10] illness forced him to return home and, once recuperated, he began school at Geauga Academy, where he discovered his lasting inspiration in academics, both learning and teaching.[11] Of this early time Garfield later said, "I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration...a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways."[12] He was in 1849 offered, and accepted, an unsought teaching position, and thereafter developed a personal rejection of "place seeking" which became "the law of my life."[13] In 1850 Garfield resumed his neglected church attendance, and was baptized.[14]

Education, marriage and early career

From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute founded by the Disciples of Christ[4] (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, where he was taught by Platt Rogers Spencer, and was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin.[15] While at Eclectic, he also was engaged to teach there, and as well developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches for a gold dollar per service.[16] Garfield then enrolled at Williams College[4] in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he was a brother of Delta Upsilon fraternity.[17] and graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student who enjoyed all subjects except chemistry.[18] Garfield was quite impressed with the college President, Mark Hopkins, about whom he said, "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other."[19] Garfield earned the reputation of a skilled debater, was made President of the Philogian Society and Editor of the Williams Quarterly.[20]

After preaching a short time at Franklin Circle Christian Church (1857–58),[4] Garfield ruled out preaching and considered a job as principal of a high school in Poestenkill, New York.[21] After losing that job to another applicant, he returned to teach at the Eclectic Institute. Garfield was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856–1857 academic year, and was made Principal of the Institute from 1857 to 1860, successfully restoring it to viability after it had previously fallen on hard times.[22] During this time, Garfield demonstrated himself politically to be clearly in agreement with the moderate positions of Republican party camp. While he did not consider himself an abolitionist, he was clearly opposed to slavery.[23] After Garfield finished his education, between the 1857 and 1858 elections, he began his career into politics as a "vigorous" stump speaker for the Republican Party and the party's anti-slavery cause. Prior to 1856, Garfield had no significant interest in politics.[24] In 1858, a migrant freethinker and evolutionary named Denton challenged him to a debate (Darwin's Origin of Species went into publication the next year.) The debate, which lasted over a week, was considered as won convincingly by the local Garfield.[25]

Garfield's first romance had been with Almeda Booth in 1851 but it lasted only a year, with no formal engagement.[26] On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph, known as "Crete" to friends, and a former star Greek pupil of Garfield's.[4][16] They had seven children (five sons and two daughters):[4] Eliza Arabella Garfield (1860–63); Harry Augustus Garfield (1863–1942); James Rudolph Garfield (1865–1950); Mary Garfield (1867–1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870–1951); Abram Garfield (1872–1958); and Edward Garfield (1874–76). One son, James R. Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt.

Garfield had gradually become discontented with his teaching vocation and began in 1859 the study of law.[27] He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1860.[4] Before admission to the bar, however, he was asked to enter politics by local Republican party leaders, upon the death of Republican Cyrus Prentiss, the presumed nominee for the state senate seat for the 26th District in Ohio. He was nominated by the party convention and then elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861.[7] Garfield's signature effort in the state legislature was a bill providing for the state's first geological survey to measure its mineral resources.[28] His initial observations about the nation leading up to the civil war were that secession was quite inconceivable.[29] His response was in part a renewed zeal for the 4th of July celebrations in 1860.[30]

After Abraham Lincoln's election, Garfield was more inclined to arms than negotiations, saying "Other states may arm to the teeth, but if Ohio so much as cleans her rusty muskets, it is said to have offended our brethren in the South. I am weary of this weakness."[31] On February 13, 1861, the newly elected President Abraham Lincoln pulled into Cincinatti, Ohio by Presidential train to make a speech. The United States was on the verge of the Civil War. Garfield was there and observed that Lincoln was "distressingly homely", yet had "the tone and bearing of a fearless, firm man."[32]

Military career

Under Buell's command

At the start of the Civil War, Garfield quickly grew anxious as well as frustrated in efforts to obtain an officer's position in the Union Army.[33] Ohio Gov. William Dennison assigned to him a mission in Illinois to acquire musketry and also to negotiate with the Governors of Illinois and Indiana for the consolidation of troops.[34] In the summer of 1861, he was finally commissioned a Colonel in the Union Army and given command of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[33]

General Don Carlos Buell assigned Colonel Garfield the task of driving Confederate forces out of eastern Kentucky in November 1861, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign. In December, he departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky, with the 40th Ohio Infantry, the 42nd Ohio Infantry, the 14th Kentucky Infantry, and the 22nd Kentucky Infantry, as well as the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry and McLoughlin's Squadron of Cavalry. The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky, where Garfield's cavalry engaged the Confederate cavalry at Jenny's Creek on January 6, 1862. Garfield artfully positioned his troops so as to deceive Marshall into thinking that he was outnumbered when in fact he was not.[35] The Confederates, under Brig. Gen. Humphrey Marshall, withdrew to the forks of Middle Creek, two miles (3 km) from Prestonsburg, Kentucky, on the road to Virginia and Garfield attacked on January 9, 1862. At the end of the day's fighting, the Confederates withdrew from the field, but Garfield did not pursue them, opting instead to order a withdrawal to Prestonsburg so he could resupply his men. His victory brought him early recognition and was used as justification for a promotion to the rank of brigadier general, on January 11.[36]

Garfield later commanded the 20th Brigade of Ohio under Buell at the Battle of Shiloh, where he led troops in an attempt, delayed by weather, to reinforce Grant, after a surprise attack by Confederate General Johnston.[37] He then served under Thomas J. Wood in the Siege of Corinth, where he assisted in the subsequent pursuit of the retreating P.T. Beauregard by the overly cautious General Halleck, which resulted in a Confederate escape. This engendered in the furious Garfield a lasting distrust of the training at West Point.[38] Garfield's philosophy of war in 1862 was not then shared by the Union leadership, i.e. to aggressively carry the war to Southern civilians, in a manner later adopted and demonstrated in the battle campaigns of Generals Sherman and Sheridan.[39]

Garfield's said the following about the slave's situation in 1862: "...if a man is black, be he friend or foe, he is thought best kept at a distance. It is hardly possible God will let us succeed while such enormities are practiced."[40] That summer, his health suddenly deteriorated, and he was forced to return home where his wife nursed him back to health and their marriage was reinvigorated.[41] That autumn he returned to duty, and he served on the Court-martial of Fitz John Porter. Garfield was then sent to Washington to receive further orders. With great frustration, he repeatedly received tentative assignments, once extended and then reversed, to stations in Florida, Virginia and South Carolina.[42] It was at this time also, during the idleness in Washington waiting for an assignment, that Garfield had an affair with Lucia Calhoun, which he later admitted to his wife, who forgave him.[43]

Chief of staff for Rosecrans

In the spring of 1863, Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland; his influence in this position was greater than normal, with Rosecrans' consent. Rosecrans, a highly energetic man, had a voracious appetite for conversation, which he deployed when he was unable to sleep; in Garfield he had found a "the first well read person in the Army" and thus the ideal candidate for endless discussions through the night.[44] The two became close, and covered all topics, especially religion; Rosecrans succeeded in softening Garfield's view of Catholicism.[45] Garfield, with his enhanced influence, created an intelligence corps unsurpassed in the Union Army.[46] But he also recommended to Rosecrans that he replace wing commanders Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden due to prior ineffectiveness. Rosecrans ignored these recommendations, with drastic consequences later, in the Battle of Chickamauga.[47] Garfield crafted a campaign designed to pursue and then trap Bragg in Tullahmoa. The army advanced to that point with success, but Bragg succeeded in retreating to Chattanooga. Rosecrans then stalled his army's move against the forces of Confederate General Braxton Bragg and instead made repeated requests for additional troops and supplies; Garfield argued with his superior for an immediate advance, also insisted upon by Lincoln and Rosecrans' commander, Gen. Halleck.[48] Garfield conceived a plan to conduct a cavalry raid behind Bragg's line (similar to that Bragg was employing against Rosecrans) which Rosecrans approved; the raid, lead by Abel Streight, failed, due in part to poor execution and weather;[49] later, Garfield's detractors contended his concept was flawed.[50] To address the disagreement over whether to advance, Rosecrans called a war council of his generals; 10 of the 15 were opposed to the move, with Garfield voting in favor. Nevertheless Garfield, in an unusual move, drew up a report of the council's deliberations, and thus convinced Rosecrans to proceed with an advance against Bragg.[51]

At the Battle of Chickamauga, Rosecrans issued an order which sought to fill a gap in his line, but which actually created one. As a result, his right flank was routed, Rosecrans concluded that the battle was lost and headed for Chattanooga to establish a defensive line; Garfield, however, thought that part of the army had held and, with Rosecrans' approval, headed across Missionary Ridge to survey the Union status. Garfield's hunch was correct and his ride became legendary, while Rosecrans' error reinforced critical opinions about his leadership.[52] While Rosecrans' army had avoided complete loss, they were left in Chattanooga surrounded by Bragg's army. Garfield fired off a telegram to Secretary Stanton, perhaps his signature act in the war, alerting Washington to the need for reinforcements to avoid annihalation. As a result, Lincoln and Halleck miraculously succeeded in delivering 20,000 troops to Chattanooga by rail within 9 days.[53] One of Grant's early decisions upon then assuming command of the Union Army was to replace Rosecrans with Thomas.[54] Garfield was issued orders to report to Washington where he was promoted to Major General;[55] shortly thereafter he gave an unambiguously abolitionist speech in Maryland.[56] Garfield was unsure of whether he should return to the field or take his Ohio congressional seat. After a discussion with Lincoln, he decided in favor of the latter, and resigned his commission.[57]

Garfield at one point had communicated his frustration with Rosecrans in a letter to his friend Secretary Chase. His opponents would later use this letter, which Chase never personally disclosed, to foster widespread criticism of Garfield for betraying his superior; this, despite the fact that Halleck and Lincoln shared the same concerns over Rosecrans reticence to attack when needed, and that Garfield had openly conveyed his complaints to Rosecrans.[58] In later years, Charles Dana of the New York Sun allegedly had sources indicating that Garfield had publicly stated that during the Battle of Chickamauga, Rosecrans had actually fled the battlefield. According to biographer Peskin, the credibility of the information and the sources used are questionable.[59] According to historian, Bruce Catton, Garfield's statements influenced the Lincoln administration to find a replacement for Rosecrans.[60]

Congressional career

Election in 1862 & first term

While serving in the field in early 1862, he was approached by friends about political opportunities resulting from the redrawing of the 19th Ohio Congressional District; it was believed that the incumbent John Hutchins was vulnerable.[61] Garfield was predictably conflicted – he was sure that he could be of more valuable service in Congress than in camp; but, he was more determined that his military position not be used as a stepping stone to political advancement. He therefore resorted to his long held objection to "place-seeking", expressed a willingness to serve if elected but otherwise left the matter to others.[62] Garfield was nominated at the Republiican convention on the 75th roll call vote.[63] In October 1862 he defeated D.B. Woods by a 2 to 1 margin in the general election for Ohio's 19th Congressional District House seat in the 38th Congress.[64]

After the election Garfield was anxious to determine his next military assignment and went to Washington for this purpose. While there he developed a close alliance with Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary.[65] Garfield became a member of the Radical Republicans, led by Chase, in contrast with the Conservative wing of the party, led by Lincoln and Montgomery Blair.[66] Demonstrating that aggressiveness is a relative concept, Garfield was as frustrated with what he perceived in Lincoln as a lack of aggressiveness in pursuing the rebel enemy as Lincoln had been with Gen. MacClellan.The two shared a disdain for West Point and the President, though Garfield applauded the Emancipation Proclamation.[67] Garfield also shared a negative view of General McClellan, whom he considered the epitomy of Democrat, proslavery, poorly trained West Point Generals.[68] And, demonstrating that aggressiveness is a relative concept, Garfield was as frustrated with what he perceived in Lincoln as a lack of aggressiveness in pursuing the rebel enemy as Lincoln had been with Gen. MacClellan.[69]

Garfield became enthralled by the economic and financial policy discussions in Chase's office, and these subjects became a lifelong passion.[70] Like Chase, Garfield became a staunch proponent of "honest money" backed by a gold standard; he regretted very much, but understood, the necessity for suspension of specie payment during the emergency presented by the civil war.[71]

Garfield took his seat in Congress upon resigning his military commission in December 1863. In that same month his first born three year old child, Eliza, died tragically.

Garfield immediately showed an ability to command the attention of the unruly House. According to a reporter, "...when he takes the floor, Garfield's voice is heard above all others. Every ear attends...his eloquent words move the heart, convince the reason, and tell the weak and wavering which way to go."[72] Although he initially took a room by himself, his grief over the death of Eliza compelled him to find a roommate, which he did, with Robert C. Schenck[73] He was re-elected every two years, from 1864 through 1878, during the Civil War and the following Reconstruction era. He was one of the more hawkish Republicans in the House, and served on Schenck's Military Affairs Committee, which brought him prominence in the midst of the predominant war issues.[74] Garfield aggressively promoted the need for a military draft, an issue almost all others shunned.[75]

Early in his tenure he bolted from his party on several issues; his was the solitary Republican vote to terminate the use of bounties in recruiting. Some financially able recruits had used the bounty system to buy their way out of service (called commutation), which he considered reprehensible.[72] Garfield, with the support of Lincoln, was able, after many false starts, to procure the passage of an aggressive conscription bill which excluded commutation.[76] In 1864, Congress passed a bill to revive the rank of Lieutenant General. Rep. Garfield, who shared the opinion of Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, was not in favor of this action, because the rank was intended for Grant, who had dismissed Rosecrans. Also, the recipient would thereby be given an advantage in possibly opposing Lincoln in the next election. Garfiled was nevertheless very tentative in his support for the President's re-election.[77]

Garfield, aligned with the Radical Republicans on some issues, not only favored abolition, but believed that the leaders of the rebellion had forfeited their constitutional rights, and supported the confiscation of southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders, as means to ensure the permanent destruction of slavery.[78] He felt congress was obliged "to determine what legislation is necessary to secure equal justice to all loyal persons, without regard to color."[79] With respect to the Presidential election of 1864, Garfield did not consider Lincoln particularly worthy of re-election, but no other viable alternative was available. "I have no candidate for President. I am a sad and sorrowful spectator of events."[80] He did attend the party convention and promoted Rosecrans for the V.P. nomination; this was greeted by Rosecrans' characteristic indecision, so the nomination went to Andrew Johnson.[81] Garfield voted with the Radical Republicans in passing the Wade-Davis bill, designed to give the Congress more authority over Reconstruction, but the bill was defeated by Lincoln's pocket veto.[82]

1864 election & term

In the 1864 Congressional election, Garfield weakened his district base by his failure to actively support to Lincoln, but this support was reinvigorated when he reminded his constituents of his need for independence from partisanship, he was nominated by acclamation, and his re-election was assured.[83] While resting after the election, Lucretia gave him a note indicating they had been together 20 out of the 57 weeks since his first election; he immediately resolved to have her and family join him in Washington from then on.[84] As the war's end approached, work on the Military Affairs Committee began to wind down; the idle time resulted in some weariness of Washington politics and also in an increased focus by Garfield on his personal finances.[85]

Garfield partnered with Ralph Plumb in land speculation, with get-rich-quick designs, but this met with limited success. He also joined with the Philadelphia based Phillips brothers in an oil exploration investment which was moderately profitable.[86] Garfield also renewed his efforts in the practice of law in 1865 as a means to improve his personal finances. Garfield's investment efforts took him to Wall Street where, the day after Lincoln's assassination, riotous behavior by a crowd led him into an impromptu speech, in part as follows: "Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!" According to witnesses, the effect was tremendous and the crowd was immediately calmed. This became one of the most well known incidents of his career.[87]

After the civil war and Lincoln's assassination, Garfield's radicalism cooled for a time, and he assumed the temporary role of peacemaker between the Congress and Andrew Johnson. At this time he said the following concerning the readmission of the confederate states: "The burden of proof rests on each of them to show whether it is fit again to enter the federal circle in full communion of privilege. They must give us proof , strong as holy writ, that they have washed their hands and are worthy again to be trusted."[88] When Johnson's veto terminated the Freedman's Bureau, he had effectively declared war with Congress and Garfield was forced back into the Radical camp.[89]

With the Military Affairs Committee's smaller agenda, Garfield was placed on the House Ways and Means Committee, giving him his long awaited opportunity to focus exclusively on financial and economic issues. He immediately reprised his opposition to the greenback, saying, "any party which commits itself to paper money will go down amid the general disaster, covered with the curses of a ruined people.";[90] he also called greenbacks "the printed lies of the government"[91] and became obsessed with the morality as well as the legality of specie payment and enforcement of the gold standard. This policy was clearly against his own personal interest. His investments were dependent upon for their profit upon inflation, the by-product of the greenback. His demand for "hard money" was distinctly deflationary in nature, and was opposed by most businessmen and politicians. For a time, he was the singular Ohio politician to take this stand.[92]

On the economic front, as a proponent of laissez-faire, he said, "the chief duty of the government is to keep the peace and stand out of the sunshine of the people."[93] This view was in stark contrast to his view of the role of government in reconstruction.[94] Another inconsistency in Garfield's laissez-faire philosophy was his position on free trade. Although he was a free trader in general, he favored the tariff out of political necessity when it served to protect products local to his district.[95]

Garfield was one of three attorneys who argued for the petitioners in the famous Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan in 1866. This was, astonishingly, Garfield's very first court appearance. Jeremiah Black had taken him in as a junior partner a year before and assigned the case to him in light of his highly reputed oratory skills. The petitioners were pro-Confederate northern men who had been found guilty and sentenced to death by a military court for treasonous activities. The case turned on whether the defendants should instead have been tried by a civilian court; Garfield was victorious, and instantly achieved a reputation as a constitutional lawyer.[96]

1866 election and third term

Despite the allure of a newly lucrative law practice, there was little hesitancy on Garfield's part in deciding to stand for re-election in 1866, due primarily to the urgency presented by Reconstruction. The competition was a bit stiffer since Garfield now had positions taken which bore defending, such as the draft legislation he supported, tariffs, and his involvement in the Milligan case.[97] As much as anyone, Harmon Austin, a local man of influence, was indispensable to Garfield's success, keeping a finger on the pulse of the district politically.[98] The party convention went smoothly in his favor, then Garfield won the election with a 5-to-2 margin. At the same time, the Republicans were taking two-thirds of the congressional seats nationwide.[99]

Ignoring his success, Garfield returned to Washington very glum, taking the campaign criticism quite hard and also disgusted at what he thought was insane talk of impeaching President Johnson. With respect to Reconstruction, he had thought the Congress to have been magnanimous in its offers to the South. When the rebels responded to this as weakness, to be taken advantage of in their demands, he was quite prepared to renew his view of them as enemies of the Union. This attitude was quite popular back home, and initiated talk of a Garfield-for-Governor campaign. Garfield promptly quashed it.[100]

Garfield expected his new term would bring an appointment as Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, but this was not to be, due largely to his emphatic position in favor of hard money, which did not reflect the House consensus.[101]; he was however given the chairmanship of the Military Affairs Committee, the primary agenda item there being the reorganization and reduction of the armed forces in order to get them on a peace footing.[102] Garfield at this time endorsed the view that the Senate, via The Tenure of Office Act, had final say on Presidential appointments, a position he would change when President himself.[103]

He supported articles of impeachment against Johnson when the President attempted to remove Secretary of War Stanton, though he was absent for the vote due to legal work. Support for impeachment was very high, but the result was in doubt due to forebodings about Vice President Wade as successor to Johnson.[104] Garfield felt senators were more interested in making speeches than conducting a proper trial. In the end, Chief Justice Chase, who presided over the trial, was thought to have brought about Johnson's acquittal by the Senate with his statements from the bench. Thus, Garfield's close friend became a political adversary, though Garfield perservered with the economic and financial views he learned from Chase.[105] In early 1868 Garfield gave his noted two-hour "Currency" speech in the House which was widely applauded as his best oratory yet; in it he advocated a gradual presumption of specie payment.[106]

1868 election and term

Garfield's competition for re-election to a fourth term was weaker than two years prior. The little opposition there was had few issues with which to take him to task. An futile attempt was made to criticize him as a free trader, when the most that could be said was that he refused to aggressively pursue higher tariffs to protect local products. His nomination went quickly at the party convention, he gave over 60 speeches in his election campaign, and was elected with a 2 to 1 margin, while Grant won the presidency.[107] At the outset, Garfield's relationship with the newly inaugurated President Grant were cool on both sides; Grant refused a requested Post Office appointment which Garfield recommended; Garfield, out of loyalty to his army commander, also harbored some resentment for Grant's dismissal of Rosecrans.[108] After six years of housing his family in rented rooms in Washington, Garfield determined to build a house of his own, at a total cost of $13,000. His close army friend, Major David Swaim loaned him half the cost.[109]

While Garfield had by this time established himself as a superb orator, in managing legislation he demonstrated little feel for the mood of the House or ability to control debate on items he brought to the floor.[110] He continued in this new term to expect the Chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee, but again this was misplaced, due in large part to his shortcomings in managing legislation on the floor; he was given the chair of the Banking and Currency Committee, but felt quite disparaged to have lost the Military Affairs Chairmanship.[111] One legislative priority of his fourth term was a bill to establish a Department of Education which succeeded, only to be brought down by poor administration by the first Commissioner of Education, Henry Barnard.[112]

Another pet project of Garfield's this term was a bill to transfer Indian Affairs from the Interior Dept. to the War Dept. His estimate was that the Indians' culture could be more effectively "civilized" with the help of the more structured and disciplined military.[113] The proposal was considered ill-conceived from the outset, but Garfield failed to pick up on this.[114] On a positive note in this term, Garfield was appointed chairman of a subcommittee on the census; as with other things mathematical, he threw himself into this head and shoulders. The two accomplishments of his work here were 1) to revamp the counting process, and 2) a major change in the questionaire. Garfield showed improvement in handling this on the House floor and it was passed there, although it was stopped in the Senate; ten years later, a similar bill became law, with most of his groundwork in place.[115]

In 1869, Garfield was chairman of a committee investigating the Black Friday Gold Panic scandal. The committee investigation into corruption was thorough, but found no indictable offenses. Garfield refused as irrelevant a request to subpoena the President's sister, whose husband was allegedly envolved in the scandal. Garfield took full advantage of the opportunity to blame the fluctuating greenback for sowing the seeds of greed and speculation leading to the scandal.[116][117]

During this term Garfield pursued his ant-inflationist campaign against the greenback through his work on the bill for a National Bank system. He successfully used the bill as a means to reduce the volume of greenbacks in circulation.[118]

1870 election and term

The election in 1870 brought with it an increased level of criticism of Garfield for his failure to support higher tariffs, especially among the iron producers in his district. He was also criticized by the free traders for what support he did give to the tariff.[119] His opponents as well accused him of wasteful and lavish spending in the construction of his new home in Washington, costing $13,000 while the average cost in the district was $2,000.[120] Nevertheless, his nomination succeeded by acclamation and he won re-election by a margin of just less than 2-to-1.[121]

As in the past, Garfield expected the leadership of the Ways and Means Committee to be his, but again it escaped him due to opposition from the influencial Horace Greeley, and he was appointed chairman of the Appropriations Committee, a position he initially spurned, but which, with time, commanded his interest, and improved his skills as a floor manager.[122] Garfield's own outlook for the Republican Party, and the Democrats as well, was negative at this point, which he described as follows: "the death of both parties is all but certain, the Democrats, because every idea they have brought forward in the past 12 years is dead, and the Republicans, because its ideas have been realized. Nevertheless, he remained a party regular.[123]

Garfield thought the land grants given to expanding railroads to be an unjust parctice; as well, he opposed monopolistic practices by corporations and as well the power sought by the workers' unions.[124] By this time, Garfield's Reconstruction philosophy had moderated. He hailed the passage of the 15th Amendment as a triumph, and he favored the re-admission of Georgia as a matter of right, not politics.[125] In 1871, However, Garfield could not support the Ku Klux Klan Act, passed by Congress on, saying "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation". He was torn between his indignation of "these terrorists" and his concern for the freedoms endangered by the power given to the President to enforce the Act through suspension of habeas corpus.[126]

Garfield supported the proposed establishment of the United States civil service, as a means of alleviating the burden of aggressive office seekers upon elected officials. He especially wished to eliminate the common practice whereby government workers, in exchange for their positions, were forced to kickback a percentage of their wages in political contributions.[127]

During this term, discontented with public service, Garfield pursued opportunities in law practice, but declined a partnership offer after being advised his prospective partner was of "intemperate and licentious" reputation.[128] Family life had also increased in importance to Garfield, who said to his wife in 1871, "When you are ill, I am like the inhabitants of a country visited by earthquakes. Like they, I lose all faith in the eternal order and fixedness of things."[129]

1872 election and later terms

Garfield was not at all enthused about the re-election of President Grant in 1872; that was until Horace Greeley emerged as the only potential alternative.[130] In terms of his own re-election, again the competition was scant if not non-existent. His district was redrawn to his advantage, he was nominated by acclamation at his convention, and went on to win re-election by a margin of 5-to-2.[131] In that year, he took his first trip west of the Mississippi, on a successful mission to conclude an agreement regarding the relocation of the Flathead Indian tribe.[132]

In 1872, he was one of a number of congressmen involved in the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. As part of their expansion efforts, the principals of the Union Pacific Railroad formed Crédit Mobilier and issued stock. Garfield, accused of improperly taking the stock, ineffectively denied the charges against him, though the scandal did not imperil his political career severely, since the details were complex and not clear. Congressman Oakes Ames testified Garfield had purchased 10 shares of Crédit Mobiler stock for $1000, received accurred stock interest and $329 in dividends sometime between December 1867 and June 1868. According to the New York Times, Garfield had been in debt at the time having taken out a mortgage on his property with borrowed money.[133]

Later in that term, Garfield found himself in the position of having to vote for his Appropriation Committee's bill which included a provision to increase Congressional and Presidential salaries, which he opposed. This controversial Act known as the "Salary Grab", was passed into law in March, 1873. Two months later in June, congressional supporters of the law received "vitriolic" response from the press and the voting public.[134] This vote was the source of a greater degree of criticism for Garfield, his public image suffered somewhat, though he was reappointed Chairman of the Appropriations Committee and placed on the Rules Committee. The vote did, however, give rise to stiffer competition in the next election.[135] He wasted no time in returning to the U.S. Treasury his own salary increase, and he found himself, and his advisor Harmon Austin, energized by the upcoming election battle. Austin perceived a need for a more structured campaign organization and wasted no time effecting it.[136]

In 1876, when James G. Blaine moved from the House to the United States Senate, Garfield became the Republican floor leader of the House.

In 1873, Rep. Garfield lobbied Pres. Ulysses S. Grant that Justice Noah H. Swayne be appointed to be Chief Justice to the United States Supreme Court. The previous Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase, had died while serving on the Court on May 7, 1873. Pres. Grant, however, appointed Morrison R. Waite.[137]

In 1876, Garfield was a Republican member of the Electoral Commission that awarded 20 hotly-contested electoral votes to Rutherford B. Hayes in his contest for the Presidency against Samuel J. Tilden. That year, he also purchased the property in Mentor that reporters later dubbed Lawnfield,[138] and from which he would conduct the first successful front porch campaign for the presidency. The home is now maintained by the National Park Service as the James A. Garfield National Historic Site.[138]

Election of 1880

In 1880, Garfield's life underwent tremendous change with help under Republican control, chose Garfield to fill Thurman's seat for the term beginning March 4, 1881.[139] However, at the Republican National Convention where Garfield supported Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman for the party's Presidential nomination, a long deadlock between the Grant and Blaine forces caused the delegates to look elsewhere for a compromise choice and on the 36th ballot Garfield was nominated. Virtually all of Blaine's and John Sherman's delegates broke ranks to vote for the dark horse nominee in the end. As it happened, the U.S. Senate seat to which Garfield had been chosen ultimately went to Sherman, whose Presidential candidacy Garfield had gone to the convention to support. Garfield's ascendancy to the 1880 Republican nomination for the Presidency over prominent Republican presidential contenders was monumental.[140]

A central controversial issue during the Election of 1880 was Chinese immigration; an issue that could make or break any Presidential contender during this time period. Those in the West, particularly California, were against Chinese immigration claiming that growth in the Pacific would be limited. Easterners, such a Senator George F. Hoar, took a more philosophical and religious stand in favor of Chinese immigration. Garfield, on July 12, 1880 favored limiting Chinese immigration, which he labeled as "an invasion to be looked upon without solicitude." However, Garfield's primary supporter in the Senate, James G. Blaine, had sent out a letter that allegedly favored Chinese immigration. It was speculated that Blaine's letter cost Garfield valuable electoral votes in California.[141][142][143]

In the general election, Garfield defeated the Democratic candidate Winfield Scott Hancock, another distinguished former Union Army general, by 214 electoral votes to 155. (The popular vote had a plurality of less than 2,000 votes out of more than 8.89 million cast; see U.S. presidential election, 1880.) He became the only man ever to be elected to the Presidency straight from the House of Representatives and was, for a short period, a sitting representative, senator-elect, and president-elect. If sworn in, he would have been the first U.S. senator to be elected president; Warren G. Harding became the first to do so forty years later. However, Garfield resigned his other positions and, on March 4, 1881, took office as President, and never sat in the Senate, where that term began on the same day.

Presidency

President Garfield had only 4 months to establish his presidency before being fatally shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a deranged political office seeker, on July 2, 1881. During his limited time in office he was able to reestablish the independence of the presidency by defying the Republican Stalwart boss, Senator Roscoe Conkling. His inaugural address set the agenda for his presidency; however, he was unable to live long enough to implement these policies. Garfield's call for civil service reform, however, was fulfilled in the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act passed by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur in 1883. Garfield's assassination was the primary motivation for the reform bill's passage. The year 2011 marks the 150th anniversary of the Civil War and 130th anniversary of President Garfield's assassination and death.

Inaugural address

Snow covered much of the Capitol grounds during Garfield's inaugural address with a low turn out, about 7,000 people, who came to inauguration. Garfield was sworn into office by Chief Justice Morrison Waite on Friday, March 4, 1881.[144][145]

The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787.[144]

...there was no middle ground for the negro race between slavery and equal citizenship. There can be no permanent disfranchised peasantry in the United States. Freedom can never yield its fullness of blessings so long as the law or its administration places the smallest obstacle in the pathway of any virtuous citizen.[144]

The nation itself is responsible for the extension of the suffrage, and is under special obligations to aid in removing the illiteracy which it has added to the voting population. For the North and South alike there is but one remedy. All the constitutional power of the nation and of the States and all the volunteer forces of the people should be surrendered to meet this danger by the savory influence of universal education.[144]

By the experience of commercial nations in all ages it has been found that gold and silver afford the only safe foundation for a monetary system. Confusion has recently been created by variations in the relative value of the two metals, but I confidently believe that arrangements can be made between the leading commercial nations which will secure the general use of both metals.[144]

The interests of agriculture deserve more attention from the Government than they have yet received. The farms of the United States afford homes and employment for more than one-half our people, and furnish much the largest part of all our exports. As the Government lights our coasts for the protection of mariners and the benefit of commerce, so it should give to the tillers of the soil the best lights of practical science and experience.[144]

The civil service can never be placed on a satisfactory basis until it is regulated by law. For the good of the service itself, for the protection of those who are intrusted with the appointing power against the waste of time and obstruction to the public business caused by the inordinate pressure for place, and for the protection of incumbents against intrigue and wrong...[144]

The Mormon Church not only offends the moral sense of manhood by sanctioning polygamy, but prevents the administration of justice through ordinary instrumentalities of law.[144]

Inaugural parade and ball

John Philip Sousa led the Marine Corps band both at the inaugural parade and ball. The ball was held in the National Museum, now the Arts and Industries Building, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.[144]

Administration and Cabinet

Between his election and his inauguration, Garfield was occupied with constructing a cabinet that would balance all Republican factions. He rewarded Blaine by appointing him Secretary of State. He also nominated William Windom of Minnesota as Secretary of the Treasury, William H. Hunt of Louisiana as Secretary of the Navy, Robert Todd Lincoln as Secretary of War, Samuel J. Kirkwood of Iowa as Secretary of the Interior. He appointed Wayne MacVeagh of Pennsylvania Attorney General. New York was represented by Thomas Lemuel James as Postmaster General.[146]

This last appointment infuriated Garfield's Stalwart rival Roscoe Conkling, who demanded nothing less for his faction and his state than the Treasury Department. The resulting squabble consumed the energies of the brief Garfield presidency. It overshadowed promising activities such as Blaine's efforts to build closer ties with Latin America, Postmaster General James's investigation of the "star route" postal frauds, and Windom's successful refinancing of the federal debt. The feud with Conkling reached a climax when the President, at Blaine's instigation, nominated Conkling's enemy, Judge William H. Robertson, to be collector of the port of New York. Conkling raised the time-honored principle of senatorial courtesy in attempting to defeat the nomination, but to no avail. Finally he and his junior colleague, Thomas C. Platt, resigned their Senate seats to seek vindication, but they found only further humiliation when the New York legislature elected others in their places. Garfield's victory was complete. He had routed his foes, weakened the principle of senatorial courtesy, and revitalized the presidential office.[147]

President Garfield's only official social function made outside the White House was a visit to the Columbia Institution for the Deaf (later Gallaudet University) in May 1881.[148]

| The Garfield cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James A. Garfield | 1881 |

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur | 1881 |

| Secretary of State | James G. Blaine | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William Windom | 1881 |

| Secretary of War | Robert Todd Lincoln | 1881 |

| Attorney General | Wayne MacVeagh | 1881 |

| Postmaster General | Thomas L. James | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Navy | William H. Hunt | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Samuel J. Kirkwood | 1881 |

Only executive order

Garfield's one and only executive order was to give executive government workers the day off on May 30, 1881, in order to decorate the graves of those who died in the Civil War.[149]

- Executive Order

- May 28, 1881

- Dear Sir:

- I am directed by the President to inform you that the several Departments of the Government will be closed on Monday, the 30th instant, to enable the employees to participate in the decoration of the graves of the soldiers who fell during the rebellion.

- Very respectfully,

- J. Stanley Brown, Private Secretary.

- Addressed to the heads of the Executive Departments, etc.

Judicial appointments

Despite his short tenure in office, Garfield was able to appoint a Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, and four other federal judges.

Supreme Court

| Judge | Seat | State | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Stanley Matthews | seat 6 | Ohio | May 12, 1881 | March 22, 1889 |

Lower courts

| Judge | Court | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Don Albert Pardee | Fifth Circuit |

May 13, 1881 | September 26, 1919[150] |

| Alexander Boarman | W.D. La. | May 18, 1881 | August 30, 1916 |

| Addison Brown | S.D.N.Y. | June 2, 1881[151] | August 30, 1901 |

| LeBaron B. Colt | D.R.I. | March 21, 1881 | July 23, 1884 |

Assassination

Garfield had little time in office. He was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, disgruntled by failed efforts to secure a federal post, on July 2, 1881, at 9:30 a.m. The President had been walking through the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (a predecessor of the Pennsylvania Railroad) in Washington, D.C. Garfield was on his way to his alma mater, Williams College, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech, accompanied by Secretary of State James G. Blaine, Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln (son of Abraham Lincoln[152]) and two of his sons, James and Harry. The station was located on the southwest corner of present day Sixth Street Northwest and Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. (The West Building of the National Gallery of Art now occupies this site; the rotunda of that building sits astride the former location of Sixth Street directly south of Constitution Avenue.) As he was being arrested after the shooting, Guiteau repeatedly said, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur is President now!"[153] which briefly led to unfounded suspicions that Arthur or his supporters had put Guiteau up to the crime. (The Stalwarts strongly opposed Garfield's Half-Breeds; like many vice presidents, Arthur was chosen for political advantage, to placate his faction, rather than for skills or loyalty to his running-mate.) Guiteau was upset because of the rejection of his repeated attempts to be appointed as the United States consul in Paris – a position for which he had absolutely no qualifications. Garfield's assassination was instrumental to the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883.

One bullet grazed Garfield's arm; the second bullet lodged in his spine and could not be found, although scientists today think that the bullet was near his lung. Alexander Graham Bell devised a metal detector specifically to find the bullet, but the device was reading the metal bed springs.[156]

Garfield became increasingly ill over a period of several weeks due to infection, which caused his heart to weaken. He remained bedridden in the White House with fevers and extreme pains. On September 6, the ailing President was moved to the Jersey Shore in the vain hope that the fresh air and quiet there might aid his recovery. In a matter of hours, local residents put down a special rail spur for Garfield's train; some of the ties are now part of the Garfield Tea House. The beach cottage Garfield was taken to has been demolished.

Garfield died of a massive heart attack or a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm, following blood poisoning and bronchial pneumonia, at 10:35 p.m. on Monday, September 19, 1881, in the Elberon section of Long Branch, New Jersey. The wounded President died exactly two months before his 50th birthday. During the eighty days between his shooting and death, his only official act was to sign an extradition paper.

Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss, (who was a Doctor of Medicine but whose given name was also "Doctor")[158][159][160][161] Garfield's chief doctor, recorded the following:

Only a moment elapsed before Mrs. Garfield was present. She exclaimed, 'Oh! what is the matter?' I said, 'Mrs. Garfield, the President is dying.' Leaning over her husband and fervently kissing his brow, she exclaimed, 'Oh! Why am I made to suffer this cruel wrong?'...Restoratives, which were always at hand, were instantly resorted to. In almost every conceivable way it was sought to revive the rapidly yielding vital forces. A faint, fluttering pulsation of the heart, gradually fading to indistinctness, alone rewarded my examinations. At last, only moments after the first alarm, at 10:35, I raised my head from the breast of my dead friend and said to the sorrowful group, 'It is over.' Noiselessly, one by one, we passed out, leaving the broken-hearted wife alone with her dead husband. Thus she remained for more than an hour, gazing upon the lifeless features, when Colonel Rockwell, fearing the effect upon her health, touched her arm and begged her to retire, which she did."[162]

Most historians and medical experts now believe that Garfield probably would have survived his wound had the doctors attending him been more capable.[163] Several inserted their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, and one doctor punctured Garfield's liver in doing so. This alone would not have caused death as the liver is one of the few organs in the human body that can regenerate itself. However, this physician probably introduced Streptococcus bacteria into the President's body and that caused blood poisoning for which at that time there were no antibiotics.

Guiteau was found guilty of assassinating Garfield, despite his lawyers raising an insanity defense. He insisted that incompetent medical care had really killed the President. Although historians generally agree that poor medical care was an element, it was not a legal defense. Guiteau was sentenced to death, and was executed by hanging on June 30, 1882, in Washington, D.C.

Garfield was buried, with great solemnity, in a mausoleum in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio.[164] The monument is decorated with five terracotta bas relief panels by sculptor Caspar Buberl, depicting various stages in Garfield's life. Originally, he was interred in a temporary brick vault in the same cemetery. In 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington, D.C. A cenotaph to him is located in Miners Union Cemetery in Bodie, California. On the grounds of the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers stands a monument to the fallen president completed in 1884; it was designed by sculptor Frank Happersberger.

At the time of his death, Garfield was survived by his mother. He is one of only three presidents to have predeceased their mothers. The others were James K. Polk and John F. Kennedy. JFK, alone among presidents, also predeceased a grandparent (his maternal grandmother).

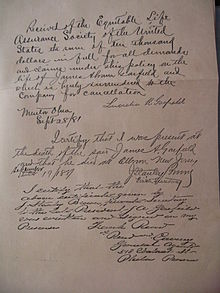

On January 12, 2010, a previously unknown life insurance policy on the life of Garfield was discovered in Orient, New York. The policy was found in a family scrap book dating from the same period of his death and had a benefit amount of $10,000. It was opened on May 18, 1881, just 45 days prior to the date Garfield was shot by Guiteau, and was surrendered and signed by Lucretia Garfield and Joseph Stanley-Brown, both witnesses to Garfield's death.[165]

The U.S. has twice had three presidents in the same year. The first such year was 1841. Martin Van Buren ended his single term, William Henry Harrison was inaugurated and died a month later, then Vice President John Tyler stepped into the vacant office. The second occurrence was in 1881. Rutherford B. Hayes relinquished the office to James A. Garfield. Upon Garfield's death, Chester A. Arthur became president.

Garfield on U.S. postage

All deceased U.S. presidents are represented on American postage stamps, but there are only a few who have appeared more than twice, and James Garfield is one of them. The first stamp issue to depict Garfield was a memorial issue, released in Garfield's memory on April 10, 1882, just seven months after his death. In contrast, the first Lincoln stamp was issued in 1866, a year after his death, while Grant would not receive his posthumous honors from the Post Office until 1890, five years after his death.

The last U.S. postage issue to depict Garfield was released on May 22, 1986 when the US Post Office released a series of 36 postage stamps commonly referred to as the AMERIPEX issues of 1986, each issue with a portrait of a past US President inscribed upon its face. In all, there are nine different Garfield postage stamps that were issued over the last 128 and more years that bear President Garfield's engraved portrait.[166]

Legacy

James Garfield was featured on the series 1882 $20 Gold Certificate,[167] a currency note considered to be of moderate rarity and quite valuable to collectors.

Garfield Avenue in the suburb of Five Dock, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia is named after James A. Garfield, as is Garfield Street in Phoenix, Arizona, Chelsea, Michigan, and the suburb of Brooklyn, Wellington, New Zealand.

Garfield County in Montana, Nebraska, Utah, and Washington are named after James A. Garfield.

Upon officially becoming a town, a Kansas settlement that went by the name Camp Riley renamed itself Garfield City to pay tribute to the politician, who once visited the settlement during military duty at the nearby Fort Larned.[168] Garfield City is now known as Garfield, Kansas and has a population of under two hundred people at the 2000 census. A sandstone statue of Garfield was dedicated in May 2009 on the campus of Hiram College. A week later, the statue was decapitated by vandals.[169] The missing head was recovered in July 2009.[170]

James A. Garfield School District is located in Garrettsville, Ohio, about 5 miles east of Hiram College, where Garfield studied, taught and later became president in 1857 at the age of 26. The district consists of 1,580 students in grades kindergarten through 12.[171]

Individual distinctions

- Garfield was a minister and an elder for the Church of Christ (Christian Church), making him the only member of the clergy to date to serve as President.[172] He is also claimed as a member of the Disciples of Christ, as the different branches did not split until the 20th century. Garfield preached his first sermon in Poestenkill, New York.[173]

- Garfield is the only person in U.S. history to be a Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect at the same time. To date, he is the only Representative to be directly elected President of the United States.

- In 1876, Garfield discovered a novel proof[174] of the Pythagorean Theorem using a trapezoid while serving as a member of the House of Representatives.[175] Tim Murphy of Mother Jones has argued that this may have been his greatest accomplishment.[176]

- Garfield was the first ambidextrous president. It was said that one could ask him a question in English and he could simultaneously write the answer in Latin with one hand, and Ancient Greek with the other, two languages he knew.[177]

- Garfield was a descendant of Mayflower passenger John Billington through his son Francis, another Mayflower passenger.[178] John Billington was convicted of murder at Plymouth Mass. 1630.[179]

- Garfield was related to Owen Tudor, and both were descendants of Rhys ap Tewdwr.[180][181]

- Garfield juggled Indian clubs to build his muscles.[182]

- Garfield was the first left-handed President.[183]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of United States presidents

- List of United States Presidents who died in office

- US Presidents on US postage stamps

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Frederic D. Schwarz "1881: President Garfield Shot," American Heritage, June/July 2006.

- ^ Ohio Historical Society

- ^ a b "James Garfield". United States Government, Biographical archives. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|<span style=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h http://jamesgarfieldfacts.com/

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.4

- ^ Ohiohistorycentral.org

- ^ a b Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 164. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Peskin (1978), p.6.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.8

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.9-12

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.13-15

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.13.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.16

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.17.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.22

- ^ a b Peskin (1978), p.28

- ^ Notable DUs. Delta Upsilon Fraternity. Politics and Government. URL retrieved February 20, 2007.[Peskin indicates Garfield shunned the Greek fraternities.]

- ^ James Garfield. American-Presidents.com. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.33.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.37.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.45.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.49.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.58.

- ^ Balch (1881), The Life of James Abram Garfield, the Late President of the United States, pp. 104-105

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.55.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.26.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.59.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.74.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.76.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.77.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.81.

- ^ Widmer, Tim (February 12, 2011). "Lincoln Elected (Again)". Retrieved 02-16-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Armyrotc.com

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.90.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.106.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.128.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.133.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.139.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.144.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.145.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.146.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.161.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.160.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.169.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.170.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.1176.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.177.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.182.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.183.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.185.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.186-189.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.206-208.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.210

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.213

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.219.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.218.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.220.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.195

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.214-217.

- ^ Catton (1965), Never Call Retreat. pp. 257, 258

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.140.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.140-142.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.147.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.148.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.151.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.238.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.152.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.163.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.237.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.154.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.156.

- ^ a b Peskin (1978), p.224.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.229.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.230.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.231.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.232.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.227.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.233.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.234.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.239.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.240.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.241.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.242.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.244.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.246.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.248.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.250.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.258.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.259.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.261.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.264.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.262.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.263.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.260.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.265.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.270.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.274.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.276.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.277.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.278.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.283.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.284.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.286.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.287.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.288.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.289.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.290-291.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.310.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.304.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.294

- ^ Peskin (1978), p301.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.295.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.297.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.298.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.306-307.

- ^ McFeely (1981), Grant, p. 328

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.311.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.313.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.315-316.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.317.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.318.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.327.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.329.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.331.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.332-333.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.334.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.335-338.

- ^ Peskin (1978), pp.347.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.348.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.349.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.349.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.352.

- ^ New York Times (June 18, 1873), Mr. Garfield's Defense.

- ^ {{cite web |title=On This Day |url=http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0607.html |accessdate=03-10-2011

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.366.

- ^ Peskin (1978), p.375.

- ^ McFeely (1981), Grant, pp. 387-389, 392.

- ^ a b NPS.gov

- ^ State legislatures, not voters, chose U.S. senators until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment.

- ^ Derby, Kevin (January 21, 2011). "Presidential Derby". Retrieved 02-06-2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ League, American Tariff (May 30, 1919). The Tariff review, Volumes 63-64. p. 344. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "Letter Accepting the Presidential Nomination". July 12, 1880. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ From 1876 to 1882, it was assumed that every candidate for political office out of necessity had to state their individual position on Chinese immigration; either in favor or against the controversial issue.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i James A. Garfield

- ^ Garfield's Inaugural Address Draft

- ^ Political corruption in America: an encyclopedia of scandals, power, and greed By Mark Grossman

- ^ Garfield, James Abram. American National Biography, 2000, American Council of Learned Societies. [page needed]

- ^ Gallaudet, Edward Miner. History of the Columbia Institution for the Deaf.

- ^ "The American Presidency Project". 1999–2010. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ The old Fifth Circuit was abolished on June 16, 1891 in favor of the newly created United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, to which Pardee was assigned by operation of law, and on which he served until his death on September 26, 1919.

- ^ Recess appointment; formally nominated on October 12, 1881, confirmed by the United States Senate on October 14, 1881, and received commission on October 14, 1881.

- ^ Mr. Lincoln's White House: Robert Todd Lincoln, The Lincoln Institute, Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ^ Doyle, Burton T. (1881). Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington: R.H. Darby. p. 61. ISBN 0104575468.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cheney, Lynne Vincent. "Mrs. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper". American Heritage Magazine. October 1975. Volume 26, Issue 6. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ^ "The attack on the President's life". Library of Congress. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ^ e.g. Bill Bryson: Made in America: an Informal History of the English Language in the United States, Black Swan, 1998, p.102.

- ^ Smithsonian National Postal Museum

- ^ "How Dr. Bliss Got His Name". New York, New York: The New York Times. 1881.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rutkow, Ira (2006). James A. Garfield. New York, New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 85. ISBN 9780805069501. OCLC 255885600.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Baxter, Albert (1891). "History of the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan". New York, New York: W.W. Munsell & Co.: 699. OCLC 6359377.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Lamb, Daniel Smith, ed. (1909). History of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia: 1817-1909. Washington, D.C.: Medical Society of the District of Columbia. p. 277. OCLC 7580275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ The Death Of President Garfield, 1881 Bliss, D. W., The Story Of President Garfield's Illness, Century Magazine (1881); Marx, Rudolph, The Health of the Presidents (1960); Taylor, John M., Garfield of Ohio (1970).

- ^ A President Felled by an Assassin and 1880’s Medical Care New York Times, July 25, 2006.

- ^ Vigil, Vicki Blum (2007). Cemeteries of Northeast Ohio: Stones, Symbols & Stories. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-025-6

- ^ Ivegotneatstuff.com

- ^ Scotts US Stamp Catalogue

- ^ Orzano, Michele. "Learning the language". Coin World. November 2, 2004. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- ^ "The Indian Question in Congress and in Kansas". Kansas State Historical Society. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|<span style=ignored (help) - ^ Associated Press (May 18, 2009). "Statue of Former President Loses Head in Ohio". cbsnews.com. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

Someone has beheaded a statue of President James Garfield that was installed last week at an Ohio college.

- ^ Brown, Shawn (July 31, 2009). "Hiram College and Village of Hiram officials announce the return of head of Garfield statue". news.hiram.edu. Hiram College Office of College Relations. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

Hiram College and Village of Hiram officials today announced that the head of the statue of James A. Garfield which was stolen on Thursday, May 14, has been returned.

[dead link] - ^ James Garfield School District

- ^ James A. Garfield Mr. President. Profiles of Our Nation's Leaders. Smithsonian Education. URL retrieved on May 11, 2007.

- ^ Sullivan, James (1927). "Chapter VI. Rensselaer County". The History of New York State, Book III. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 2007-03-20. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Planethmatch.org

- ^ "Pythagoras and President Garfield", PBS Teacher Source, URL retrieved on February 1, 2007.

- ^ Murphy, Tim (2011-02-21) Listen: 44 Presidents, 44 Songs, Mother Jones

- ^ American Presidents: Life Portraits, C-SPAN, Retrieved November 29, 2006

- ^ "Famous Descendants of Mayflower Passengers". Mayflower History. URL retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ^ Borowitz, Alfred. "The Mayflower Murderer". The University of Texas at Austin. Tarlton Law Library. URL retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Genealogy Report: Ancestors of Pres. James Abram Garfield

- ^ The Titi Tudorancea Bulletin

- ^ Paletta, Lu Ann (1988). The World Almanac of Presidential Facts. World Almanac Books. ISBN 0345348885.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tenzer Feldman, Ruth (2005). James A. Garfield. Lerner Publications. ISBN 0822513986.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield, Avalon Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-7867-1396-8

- Freemon, Frank R., 2001: Gangrene and glory: medical care during the American Civil War; Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07010-0

- King, Lester Snow: 1991 Transformations in American Medicine : from Benjamin Rush to William Osler / Lester S. King. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, c1991. ISBN 0-8018-4057-0

- Peskin, Allan "James A. Garfield: Supreme Court Counsel" in Gross, Norman, ed., America's Lawyer-Presidents: From Law Office to Oval Office, Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the American Bar Association Museum of Law, 2004, pp. 164–173. ISBN 0-8101-1218-3

- Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield: A Biography. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-210-2.

- Vowell, Sarah "Assassination Vacation", Simon & Schuster, 2005 ISBN 0-7432-6004-X

- "Mr. Garfield's Defense". New York Times. June 18, 1873. Retrieved 03-10-2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

External links

- James Garfield: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Garfield, Harding, and Arthur

- Official whitehouse.gov biography

- Inaugural Address

- Encarta (Archived October 31, 2009)

- An image of Garfield's Civil War Pension File from the National Archives

- Raw Deal

- Biography from John T. Brown's Churches of Christ (1904)

- James A Garfield National Historic Site

- James A. Garfield Birthplace

- James A. Garfield at Findagrave

- Garfield Monument

- United States Congress. "James A. Garfield (id: G000063)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on February 12, 2008

- Extensive essay on James Garfield and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Articles with inconsistent citation formats

- James A. Garfield

- 1831 births

- 1881 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of the United States

- American Disciples of Christ

- American members of the Churches of Christ

- American politicians of French descent

- Assassinated United States Presidents

- Burials at Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) clergy

- Deaths by firearm in New Jersey

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Deaths from sepsis

- Hiram College alumni

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Infectious disease deaths in New Jersey

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

- Ministers of the Churches of Christ

- Ohio lawyers

- Ohio Republicans

- People from Mentor, Ohio

- People murdered in Washington, D.C.

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Presidents of the United States

- Republican Party (United States) presidential nominees

- Republican Party Presidents of the United States

- Union Army generals

- United States Army generals

- United States presidential candidates, 1880

- Williams College alumni