Libyan civil war (2011)

A request that this article title be changed to Libyan Civil War is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (March 2011) |

| Libyan uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of 2010–11 Middle East and North Africa protests | |||||||

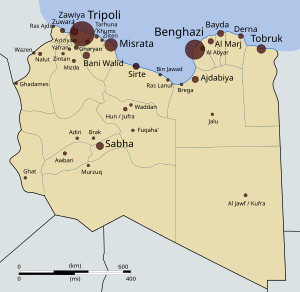

(situation as of 20th March) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Pro-Gaddafi forces:

|

Anti-Gaddafi forces:

Limited/Alleged: Template:Collapsible bulletlist | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000–12,000 (Al Jazeera estimate)[14] |

8,000 defected soldiers (in Benghazi)[15] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 385-448 soldiers killed, (see here) |

1,633 opposition fighters killed (see here) International Forces: No casualties | ||||||

|

Total number of people killed on both sides, includes protesters, rebel fighters, captives executed, government forces killed and civilians killed by NATO bombing: 1,000 killed (UN) (by 7 March)[6] 2,000 killed (WHO) (by 2 March)[18] 3,000 killed (IFHR) (by 5 March)[19] 6,000 killed (LHRL) (by 5 March)[19] 8,000 killed (NTC) (by 20 March)[20] 10,000 killed (ICC) (by 7 March)[21] | |||||||

Template:Campaignbox 2011 Libyan protests

The 2011 Libyan uprising is an ongoing armed conflict in the North African state of Libya against Muammar Gaddafi's 42-year rule, with protesters calling for his ousting and democratic elections. The uprising began as a series of protests and confrontations beginning 15 February 2011. Within a week, the uprising had spread Gaddafi was struggling to retain control across the country except for his stronghold in Tripoli, where Gaddafi.[22] Gaddafi responded with censorship, blocking of communications, and deadly military force. With many of Gaddafi military in the east defecting to the rebels, he has resorted to recruiting domestic and foreign mercenaries to supplement his forces. By the end of February the uprising had escalated into an armed conflict Gaddafi holding Tripoli and the rebels forming a government called the National Transitional Council based in Benghazi. International human rights organizations and locals have documented severe human rights abuses. The International Criminal Court has warned Gaddafi that he and members of his regime may have committed crimes against humanity.[23] Gaddafi has vowed to stay in power at all costs. In early March, Gaddafi's forces rallied, push eastwards and re-took several coastal cities including Brega, Ra's Lanuf and Bin Jawad. Gaddafi then declared a cease-fire on 18 March, though he continued to bomb and shell Misurata and on 19 March began an attack on Benghazi. The United Nations declared and begun to enforce no-fly zones against Gaddafi and inflicted numerous air strikes on his air defences and ammunition depots around Tripoli.

Much of the world has strongly condemned Gaddafi's use of violence against civilians.[24] A number of countries imposed sanctions on Gaddafi, many including travel bans and freezing of the family's multibillion assets. The United Nations Security Council passed an initial resolution freezing the assets of Gaddafi and ten members of his inner circle and restricting their travel. The resolution also referred the regime in Tripoli to the International Criminal Court for investigation.[25] On 10 March, France became the first country to recognize the National Transitional Council as the official government of Libya.[26] On 17 March, a further resolution was announced which authorized member states to enforce a no-fly zone over Libya and "to take all necessary measures... to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force".[27] In response to this the Gaddaffi regime anounced a ceasefire, which they failed to uphold. On 19 March, France and the United Kingdom officially announced that they will lead the United Nations Coalition with Operation Ellamy and Opération Harmattan to enforce the resolution. A dozen other countries joined the coalition. On the same day, a series of strikes disabled Gaddafi's air defenses and coalitions jets started enforcing the resolution.[28]

Background

History

Gaddafi has ruled Libya as de facto autocrat since overthrowing the short-lived constitutional monarchy in 1969.[29] WikiLeaks' disclosure of confidential US diplomatic cables has revealed US diplomats there speaking of Gaddafi's "mastery of tactical maneuvering".[30] While placing relatives and loyal members of his tribe in central military and government positions, he has skilfully marginalized supporters and rivals, thus maintaining a delicate balance of powers, stability and economic developments. This extends even to his own children, as he changes affections to avoid the rise of a clear successor and rival.[30] Petroleum revenues contribute up to 58% of Libya's GDP.[31] Governments with "resource curse" revenue have a lower need for taxes from other industries and consequently are less willing to develop their middle class. To calm down opposition, such governments can use the income from natural resources to offer services to the population, or to specific government supporters.[32] The government of Libya can utilize these techniques by using the national oil resources.[33] Libya's oil wealth was spread over a relatively small population of six million,[34] with 21% general unemployment, the highest in the region, according to the latest census figures.[35]

Libya's purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP per capita in 2010 was US $14,878; its human development index in 2010 was 0.755; and its literacy rate in 2009 was 87%. These numbers were lower in Egypt and Tunisia.[36] Indeed, Libyan citizens are considered to be well educated and to have a high standard of living.[37] Its corruption perception index in 2010 was 2.2, which was worse than that of Egypt and Tunisia, two neighboring countries who faced uprising before Libya.[38] This specific situation creates a wider contrast between good education, high demand for democracy, and the government's practices (perceived corruption, political system, supply of democracy).[36] Much of the country's income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring militancy and terror around the world.[39][40] Once a breadbasket of the ancient world, the eastern parts of the country became impoverished under Gaddafi's economic theories.[41][42] The uprising has been viewed as a part of the 2010–2011 Middle East and North Africa protests which has already resulted in the ousting of long-term presidents of adjacent Tunisia and Egypt with the initial protests all using similar slogans.[43] Social media had played an important role in organizing the opposition.[44]

Human rights

According to the 2009 Freedom of the Press Index, Libya is the most-censored country in the Middle East and North Africa.[45] Gaddafi's revolutionary committees resemble the systems of historical and current regimes and reportedly ten to twenty percent of Libyans work in surveillance for these committees, a proportion of informants on par with Saddam Hussein's Iraq or Kim Jong-il's North Korea.

The surveillance takes place in government, in factories, and in the education sector.[46] Engaging in political conversations with foreigners is a crime punishable by three years of prison in most cases. Gaddafi removed foreign languages from school curriculum for a decade.[47][48] Gaddafi has paid for murders of his critics around the world.[46][49] As of 2004, Libya still provided bounties for critics, including US$1 million for Ashur Shamis, a Libyan-British journalist.[50] The regime has often executed opposition activists publicly and the executions are rebroadcast on state television channels.[46][51]

Anti-Gaddafi movement

The protests and confrontations began in earnest on 15 February 2011. Social media had played an important role in organizing the opposition.[44] On 17 February, a "Day of Revolt" was called by Libyans.[52][53]

Between 13 and 16 January, upset at delays in the building of housing units and over political corruption, protesters in Darnah, Benghazi, Bani Walid and other cities broke into and occupied housing that the government was building.[56][57] On 24 January 2010, Libya blocked access to YouTube after it featured videos of demonstrations in the Libyan city of Benghazi by families of detainees who were killed in the 1996 Abu Salim prison massacre. The blocking was criticized by Human Rights Watch.[58] By 27 January, the government had responded to the housing unrest with a US$24 billion investment fund to provide housing and development.[59]

In late January, Jamal al-Hajji, a writer, political commentator and accountant, "call[ed] on the internet for demonstrations to be held in support of greater freedoms in Libya" inspired by the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings. He was arrested on 1 February by plain-clothes police officers, and charged on 3 February with injuring someone with his car. Amnesty International claimed that because al-Hajji had previously been imprisoned for his non-violent political opinions, the real reason for the present arrest appeared to be his call for demonstrations.[60] In early February, Gaddafi met with political activists, journalists, and media figures and warned them that they would be held responsible if they disturbed the peace or created chaos in Libya.[61]

Human rights

Free speech is reportedly practiced for the first time. An opposition-controlled newspaper called Libya has appeared in Benghazi, as well as opposition-controlled radio stations.[62] The movement opposes tribalism and defected soldiers wear vests bearing slogans such as "No to tribalism, no to factionalism".[42] Libyans have said that they have found abandoned torture chambers and devices that have been used against opposition members in the past.[63]

Organization

Many protest movement leaders have called for return to the 1952 constitution and transition to multiparty democracy. Military units who have joined the rebellion and many volunteers have formed an army to defend against Gaddafi's attacks and help liberate the capital Tripoli from his rule.[64] In Tobruk, volunteers turned a former headquarters of the regime into a center for helping protesters. Volunteers reportedly guard the port, local banks and oil terminals to keep the oil flowing. Teachers and engineers have set up a committee to collect weapons.[42]

The National Transitional Council (Arabic: المجلس الوطني الانتقالي) was a body established by opposition forces on 27 February in an effort to consolidate the anti-Gaddafi forces.[65] The main objectives of the group do not include forming an interim government, but instead to coordinate resistance efforts between the different towns held in rebel control, and to give a political "face" to the opposition to present to the world.[66] The Benghazi-based opposition government has called for a no-fly zone and airstrikes against the Gaddafi regime.[67] The council refers to the Libyan state as the Libyan Republic and it now has a website.[68] Gaddafi's former Justice Minister said in February that the new government will prepare for elections and they could be held in three months.[69]

Gaddafi's response

Gaddafi has attributed the protests against his rule to people who are "rats" and "cockroaches", terms that were cited by Hutu radicals of the Tutsi population before the 1994 Rwanda genocide began, thus causing unease in the global community. Gaddafi has accused his opponents as those who have been influenced by hallucinogenic drugs put in drinks and pills. He has specifically referred to substances in milk, coffee and Nescafé. He has claimed that Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda are distributing these hallucinogenic drugs. He has also blamed alcohol.[70][71][72][73] He later also claimed that the revolt against his rule is the result of a "colonialist plot" by foreign countries, particularly blaming France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to "control oil" and "enslave" Libyan people. Gaddafi vowed to "cleanse Libya house by house" until he had crushed the insurrection.[74][75][76][77][78] Gaddafi declared that people who don't "love" him "do not deserve to live".[75][77]

International journalists were banned[79][80] by the Libyan authorities[81] from reporting from Libya except by invitation of the Gaddafi government.

Mercenaries

Numerous eyewitnesses and identity documents of captured soldiers show that Gaddafi is employing foreign nationalities to attack Libyan civilians. French-speaking fighters apparently come from neighbouring African countries such as Chad and Niger.[82] However, some have urged caution, saying that Libya has a significant black population who could be mistaken for mercenaries but are actually serving in the regular army.[83] Also, many Chadian soldiers who fought for Gaddafi in past conflicts with Chad were given Libyan citizenship.[83] There have been reports of the Gadaffi regime employing mercenaries from the Democratic Republic of Congo,Mali, Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco, Kenya and possibly even Asia and Eastern Europe.[84][85] Speculation that members of the Zimbabwe National Army were covertly fighting in Libya grew as Zimbabwe’s Defence Minister Emmerson Mnangagwa avoided giving a clear answer to a question on the topic posed in Parliament.[86]

The Serbian Ministry of Defence denied rumors that of any of its active or retired personnel participating in the events in Libya.[87] The Foreign Ministry of Chad denied allegations that mercenaries were fighting for Gaddafi, although he admitted it was possible that individuals had joined such groups.[88]

Military conflict

By the end of 23 February, headlines in online news services were reporting a range of themes underlining the precarious state of the regime – former justice minister Mustafa Mohamed Abud Al Jeleil alleged that Gaddafi personally ordered the 1988 Lockerbie bombing,[89] resignations and defections of close allies,[90] the loss of Benghazi, the second largest city in Libya, reported to be "alive with celebration"[91] and other cities including Tobruk and Misurata reportedly falling[92] with some reports that the government retained control of just a few pockets,[90] mounting international isolation and pressure,[90][93] and reports that Middle East media consider the end of his "disintegrating"[94] regime all but inevitable.[94]

After taking over the city of Zawiya on 24 February, Gaddafi's troops attacked the outskirts of the city on 28 February, but were repelled. The town of Nalut, on the Tunisian border, had also fallen to the opposition forces. On 2 March, government forces attempted to recapture the oil port town of Brega, but the attack failed and they retreated to Ra's Lanuf. Rebel forces advanced following their victory and on 4 March, the opposition captured Ra's Lanuf. On the same day, government troops started a full-scale assault on Zawiyah with tank, artillery and air strikes. On 6 March, the rebel advance along the coastline had been stopped by government forces at the town of Bin Jawad. Government troops had ambushed the rebel coloumn and dozens of rebels were killed. At the same time, Gaddafi's forces attempted an attack on Misurata and mannaged to get as far as the centre of the city before their attack was stopped and they retreated to the city's outskirts.[95]

On 10 March, Zawiyah and Ra's Lanuf were retaken by Gaddafi's forces.[96][97] By March 15, the town of Brega had also been recaptured by Gaddafi's forces and the rebel city of Ajdabiya, the last town before Benghazi, was surrounded. On 17 March, the United Nations Security Council voted to imposed a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace,[98] with British, French and Arab aircraft potentially launching airstrikes within hours of its imposition. As a result of the UN resolution, on 18 March, Gaddafi's government declared an immediate ceasefire,[99] but a few hours later, Al Jazeera reported that Government forces are still fighting with rebels.[100]

Territory controlled by each side

By the end of February, Gaddafi had lost control of a significant part of the country, including the major cities of Misurata and Benghazi, and the important harbours at Ra's Lanuf and Mersa Brega.[101][102] The Libyan opposition had formed a National Transitional Council and a free press had begun to operate in Cyrenaica.[103]

On 6 March, the Gaddafi regime launched a counter-offensive, retaking Ra's Lanuf and Mersa Brega, pushing towards Ajdabiya and Benghazi. Gaddafi has remained in continuous control of Tripoli,[104] Sirt,[105] Zliten[106] and Sabha,[107] as well as several other towns.

Gaddafi controls the well-armed Khamis Brigade, among other loyalist military and police units, and some believe a small number of foreign mercenaries.[108] Some of Gaddafi's officials, as well as a number of current and retired military personnel, have sided with the protesters and requested outside help in bringing an end to massacres of non-combatants.

As of 17 March, out of Libya's twenty-two districts, twelve were under government control, seven were under rebel control and three were contested territories (see map).

Libyan fighting around Benghazi

On 18 March, the Libyan government declared an "immediate" ceasefire.[109] Even after the government-declared ceasefire, artillery shelling on Misurata and Ajdabiya continued, and government soldiers continued approaching Benghazi.[110][111] BBC News reported that government tanks entered the city on 19 March while hundreds fled the fighting.[112] Artillery and mortars were also fired into the city.[113]

Also on 19 March, a Mig-23BN was shot down over Benghazi by ground fire. A rebel spokesman later confirmed that the plane belonged to the Free Libyan Air Force and had been engaged in error by rebels.[6][114] [115] [116] [117] [118][119][120]

The Libyan government said the rebels violated the UN "no fly" resolution by using a helicopter and a fighter jet to bomb Libyan armed forces.[121]

UN no-fly zone actions

At 1600 GMT, 19 March, BBC News reported that the French Air Force had sent 19 fighter planes over an area 100 km by 150 km (60 by 100 miles) over Benghazi to prevent any attacks on the rebel controlled city.[122] "Our air force will oppose any aggression by Colonel Gadhafi against the population of Benghazi," said French President Nicolas Sarkozy. BBC News reported at 16:59 GMT that at 16:45 GMT a French warplane had fired at and destroyed a Libyan military vehicle – this being confirmed by French defence ministry spokesman Laurent Teisseire.[123]

At 2031 GMT the Pentagon announced that U.S. and British forces had fired 114+ Tomahawk cruise missiles targeting 20 Libyan integrated air and ground defense systems.[124] 25 coalition ships, including 3 U.S. submarines, are in the area.[125][126][127][128] CBS New's David Martin reported that 3 B-2 stealth bombers flew non-stop from the United States to drop 40 bombs on a major Libyan airfield. Martin further reported that US fighter jets are searching for Libyan ground forces to attack. On Sunday, around 1500 CST, Pentagon officials confirmed this.[129][130]

Libyan State TV reported that Libyan forces had shot down a French warplane over Tripoli.[125] France's military denied earlier reports from Libyan state TV that a French aircraft had been shot down and reported that all planes had returned to their air bases.[131] On 20 March 2011, several Storm Shadow missiles have been launched against Gaddafi by British jets.[132] Also, sustained anti-aircraft fire erupted in Tripoli at around 2:33 a.m. Libyan time.[133] Gaddafi's forces claimed they had shot down two planes, which was denied by the United States.[134]

Humanitarian situation

Medical supplies, fuel and food have run dangerously low in the country.[135] On 25 February, the International Committee of the Red Cross launched an emergency appeal for US$6,400,000 to meet the emergency needs of people affected by the violent unrest in the country.[136] On 2 March, the ICRC's director general reminded everyone taking part in the violence that health workers must be allowed to do their jobs safely.[137]

Fleeing the violence of Tripoli by road, as many as 4,000 people were crossing the Libya-Tunisia border daily during the first days of the uprising. Among those escaping the violence were foreign nationals including Egyptians, Tunisians and Turks – as well as Libyans.[138] By 1 March, officials from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees had confirmed allegations of discrimination against sub-Saharan Africans who were held in dangerous conditions in the no-man's-land between Tunisia and Libya.[139] By 3 March, an estimated 200,000 refugees had fled Libya to either Tunisia or Egypt. A provisional refugee camp was set up at Ras Ejder with a capacity for 10,000 was overflowing with an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 refugees. Many tens of thousands were still trapped on the Libyan side of the frontier. By 3 March, the situation was described as a logistical nightmare, with the World Health Organization warning of the risk of epidemics.[140]

With a migrant population of about two million, countries that border Libya, especially Egypt and Tunisia, have been receiving a flow of migrants and nationals escaping the violence. Migrants workers as well as Libyan nationals have been finding their way to the border cities of Sallum in Egypt and Ras Ajdir in Tunisia creating a humanitarian crisis. According to the International Organization for Migration, as of 7 March, 115,399 migrants had arrived in Tunisia (19,184 of them Tunisians, 47,631 Egyptians and the rest from various nationalities), 101,609 in Egypt (of which 65,509 were Egyptian), 2,205 in Niger (1,865 Nigeriens) and 5,448 in Algeria.[141]

Casualties

Independent numbers of dead and injured in the conflict have still not been made available. Estimates have been widely varied. Conservative estimates have put the death toll at 1,000,[6] Whereas the International Criminal Court estimated 10,000 killed on 7 March.[21] The numbers of injured were estimated to be around 4,000 by 22 February.[142] On 2 March, The International Federation for Human Rights estimated a death toll as high as 3,000 and the World Health Organization estimated approximately 2,000 killed.[18] At the same time, the opposition claimed that 6,500 people had died.[143] The Libyan Human Rights League estimated 6,000 killed on 5 March.[19][19] Later, Rebel spokesman Abdel Hafiz Ghoga reported that the death toll reached 8,000. [144]

Domestic responses

Several officials resigned from their positions after 20 February in large part due to protests against the army's "excessive use of force", including justice minister Mustafa Mohamed Abud Al Jeleil as well as Interior Minister and Major General Abdul Fatah Younis,[145] whereas Oil Minister Shukri Ghanem was reported to have fled the country.[146] Citing "grave violations of human rights", Gaddafi's cousin and close aide, Ahmad Qadhaf al-Dam, announced his defection from the government when he arrived in Egypt on 24 February.[147]

Several members of the diplomatic corps also resigned. Amongst these were the ambassadors to the Arab League,[148] Bangladesh, the People's Republic of China,[149] the European Union and Belgium,[150] India,[151] Indonesia,[146] Nigeria, Sweden and the United States. The deputy ambassador to the UN Ibrahim Omar Al Dabashi did not resign but distanced himself from the Libyan government's actions.[152][153] The ambassador to the United States Ali Aujali together with the embassy staff also distanced himself from the government, "condemned" the violence and urged the international community (QTO STOP THE KILLINGS.) The ambassador to the United Kingdom denied reports that he had resigned.[146]

The Arabian Gulf Oil Company, the second largest state-owned oil company in Libya, announced plans to use oil funds to support anti-Gaddafi forces.[154] This will prove a major boost for the embattled rebel forces low on funds.

Two Libyan Air Force pilots[citation needed] and a naval vessel fled to Malta, reportedly claiming to have refused orders to bomb protesters in Benghazi.[155][156]

Islamic leaders and clerics in Libya, notably the Network of Free Ulema – Libya urged all Muslims to rebel against Gaddafi.[146][157] The Warfalla, Tuareg and Magarha tribes have announced their support of the protesters.[101][158] The Zuwayya tribe, based in eastern Libya, have threatened to cut off oil exports from fields in their part of the country if Libyan security forces continued attacking demonstrators.[158]

Youssef Sawani, a senior aide to Muammer Gaddafi's son Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, resigned from his post "to express dismay against violence".[101]

On 28 February, Gaddafi reportedly appointed the head of Libya's foreign intelligence service to speak to the leadership of the anti-government protesters in the east of the country.[159]

Libyan-throne claimant, Muhammad as-Senussi, sent his condolences "for the heroes who have laid down their lives, killed by the brutal forces of Gaddafi" and called on the international community "to halt all support for the dictator with immediate effect."[161] as-Senussi said that the protesters would be "victorious in the end" and calls for international support to end the violence.[162] On 24 February, as-Senussi gave an interview to Al Jazeera English where he called upon the international community to help remove Gaddafi from power and stop the ongoing "massacre".[163] He has dismissed talk of a civil war saying "The Libyan people and the tribes have proven they are united". He later stated that international community needs "less talk and more action" to stop the violence.[164] He has asked for a no-fly zone over Libya but does not support foreign ground troops.[165] On March 17 he returned to Libya after 41 years in exile.[166]

In an interview with Adnkronos, Idris al-Senussi, a pretender to the Libyan throne, announced he was ready to return to the country once change had been initiated.[167] On 21 February 2011, Idris made an appearance on Piers Morgan Tonight to discuss the uprising.[168] On 3 March, it was reported that Prince Al Senussi Zouber Al Senussi had fled Libya with his family and was seeking asylum in Totebo, Sweden.[169]

International reactions

Official responses

A number of states and supranational bodies condemned Gaddafi's use of military and mercenaries against Libyan civilians. However, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, Cuban political leader Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez all expressed support for Gaddafi.[170][171][172] Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi initially said he did not want to disturb Gaddafi, but two days later he called the attacks on protesters unacceptable.[173][174]

The Arab League suspended Libya from taking part in council meetings at an emergency meeting on 22 February and issued a statement condemning the "crimes against the current peaceful popular protests and demonstrations in several Libyan cities".[175][176] Libya was suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council by a unanimous vote of the United Nations General Assembly, citing the Gaddafi government's use of violence against protesters.[177] On 26 February, the United Nations Security Council voted unanimously to impose strict sanctions against Gaddafi's government and, refer Gaddafi and other members of his regime to the International Criminal Court for investigation into allegations of brutality against civilians.[178] Interpol issued a security alert concerning the "possible movement of dangerous individuals and assets" based on the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970, listing Gaddafi himself and fifteen members of his clan or his regime.[179] A number of governments, including Britain, Canada, Switzerland, the United States, Germany and Australia took action to freeze assets of Gaddafi and his associates.[180] The Gulf Cooperation Council issued a joint statement on 8 March, calling on the United Nations Security Council to impose an air embargo on Libya to protect civilians.[181] The Arab League did the same on 12 March, with only Algeria and Syria voting against the measure.[182]

Evacuations

During the uprising, many countries evacuated their citizens.[183] China set up its largest evacuation operation ever with over 30,000 Chinese nationals evacuated, as well as 2,100 citizens from twelve other countries.[184][185][186] On 25 February, 500 passengers, mostly Americans, sailed into Malta after a rough eight-hour journey from Tripoli following a two-day wait for the seas to calm.[187] South Korea evacuated 12,000 people [clarification needed], utilizing airplanes and ferries, to Malta.[188][189] Bulgaria also evacuated some of its citizens with planes, along with Romanian and Chinese citizens.[190] Indian government launched Operation Safe Homecoming and evacuated 15,000 of its nationals.[191] The Turkish government sent three ships to evacuate a reported 25,000 Turkish workers and return them to Istanbul.[192] The Irish Department of Foreign Affairs assisted over 115 Irish nationals in leaving Libya.[193] A number of international oil companies decided to withdraw their employees from Libya to ensure their safety, including Gazprom, Royal Dutch Shell, Sinopec, Suncor Energy, Pertamina and BP. Other companies that decided to evacuate their employees included Siemens and Russian Railways.[194][195]

Several Russians, 21 Tadjiks and some Kazachs were evacuated by Russia at the same time.[196]

The evacuations often involved assistance from various military forces. The United Kingdom deployed aircrafts and the frigate HMS Cumberland to assist in the evacuations.[197][198][199] China's frigate Xuzhou of the People's Liberation Army Navy was ordered to guard the Chinese evacuation efforts.[185][200] The South Korean Navy destroyer ROKS Choi Young arrived off the coast of Tripoli on 1 March to evacuate South Korean citizens.[201] The UK Royal Navy destroyer HMS York docked in the port of Benghazi on 2 March, evacuated 43 nationals, and delivered medical supplies and other humanitarian aid donated by the Swedish government.[202][203] Canada deployed the frigate HMCS Charlottetown to aid in the evacuation of Canadian citizens and to provide humanitarian relief operations in conjunction with an US Navy carrier strike group, led by the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.[204] Two Royal Air Force C-130 Hercules aircraft with British Special Forces onboard evacuated approximately 100 foreign nationals, mainly oil workers, to Malta from the desert south of Benghazi.[205][206] A subsequent joint evacuation operation between the United Kingdom and Germany evacuated 22 Germans and about 100 other Europeans, mostly British oil workers, from the airport at Nafurah to Crete.[207][208][209] An attempt by the Royal Netherlands Navy frigate HNLMS Tromp on 27 February to evacuate a Dutch civilian and another European from the coastal city of Sirt by helicopter failed after its 3-man crew was apprehended by Libyan forces loyal to Gaddafi for infiltrating Libyan airspace without clearance.[210][211] The civilians were released soon after and the crew was released 12 days later, but the helicopter was confiscated.[212] . Also a cruise ship arrived in Libya to evcuate the filipinos in Libya only Filipino Nurses are left behind to care for the rebel forces .

Mediation proposals

There have been several peace mediation prospects during the crisis.The South African government proposed an African Union-led mediation effort to prevent civil war.[213] Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez also put himself forward as a mediator. Although Gaddafi accepted in principle a proposal by Chávez to negotiate a settlement between the opposition and the Libyan government, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi later voiced some skepticism to the proposal.[citation needed] The proposal has also been under consideration by the Arab League, according to its Secretary-General Amr Moussa.[214] The Libyan opposition has stated any deal would have to involve Gaddafi stepping down. The United States and French governments also dismissed any initiative that would allow Gaddafi to remain in power.[215] Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan, 2010 winner of the al-Gaddafi prize for Human Rights, has offered to mediate the crisis, and proposed that Gaddafi appoint a president acceptable to all Libyans as means of overcoming the crisis.[216]

Coalition intervention

(no-fly zone and other measures) |

| Countries committed to enforcement:[clarification needed] |

On 28 February, UK Prime Minister David Cameron proposed the idea of a no-fly zone to prevent Gaddafi from airlifting mercenaries and using his military aeroplanes and armoured helicopters against civilians.[229] Italy said it would support a no-fly zone if it was backed by the UN.[230] US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has been skeptical of this option, warning the US Congress that a no-fly zone would have to begin with an attack on Libya's air defenses.[231] This proposal was rejected by Russia and China.[232][233][234][235] Romania is utterly against the initiation of a no-fly zone.[236] "Among the arguments I want to bring in order to support our position is that this mission of initiating a no fly zone is a mission that only NATO can have and not the EU. We also consider it is not the moment for a military solution in Libya," said Romanian President Traian Băsescu at the EU summit on 11 March.

On 7 March, United States Permanent Representative to NATO Ivo Daalder announced that NATO decided to step up surveillance missions to twenty-four hours a day. On the same day, it was reported that one United Nations diplomat confirmed to Agence France-Presse on condition of anonymity that France and Britain were drawing up a resolution on the no-fly zone and it go before the United Nations Security Council as early as this week.[237][238]

On 12 March, the foreign ministers of the Arab League agreed to ask the United Nations to impose a no-fly zone over Libya. That brought a joint NATO/Arab-enforced fly-zone closer to establishment. The rebels have stated that a no-fly zone alone would not be enough, because the majority of the bombardment is coming from things other than aircraft – particularly tanks and rockets.[239]

On 17 March, the United Nations Security Council approved Resolution 1973 (2011), allowing for a no-fly zone, amongst other measures, by a vote of ten in favor, zero against, and five abstentions. Resolution 1973 bans all flights in Libyan airspace in order to protect civilians[240] and authorizes member states "to take all necessary measures... to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamhariya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force".[241][242] Changing its position, the United States joined the initial supporters of the UN no-fly resolution, Britain, France and Lebanon, to urge for a stronger resolution that allowed military action short of ground troups to protect civilians from air, land and sea attacks by Gadhafi's fighters.[240] British Foreign Secretary William Hague said the three criteria for taking action all have been fulfilled. The criteria for taking action – a demonstrated need, clear legal basis and broad regional support – have all been met according to Hague.[240]

Operation Ellamy, Operation Odyssey Dawn, Opération Harmattan, and Operation MOBILE are the codenames for the British, American, French, and Canadian participations in the no-fly zone respectively.[243]

On 1 March, Russian NATO ambassador Dmitry Rogozin stated that: "A ban on the national air force or civil aviation to fly over their own territory is ... a serious interference into the domestic affairs of another country".[244] On 18 March 2011, Chairman of the Russian State Duma International Affairs Committee Konstantin Kosachyov said that air strikes on Libya might "spark a huge conflict between the so-called West and the so-called Arab world."[245] China and India have also criticised military intervention, with India's foreign ministry saying "the measures adopted should mitigate and not exacerbate an already difficult situation for the people of Libya".[246]

See also

- 2011 Egyptian revolution

- International reactions to the 2011 Libyan uprising

- 2010–2011 Arab world protests

- List of modern conflicts in North Africa

- Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution

References

- ^ "Ferocious Battles in Libya as National Council Meets for First Time". News. 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Tribal Revolt May Mean Last Nail in Coffin for Qaddafi". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Levinson, Charles. "Egypt Said to Arm Libya Rebels - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Egyptian Special Forces Secretly Storm Libya". Daily Mirror. UK. 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya shuts air space in face of strikes", The Northern Star, AU, 18 March 2011

- ^ a b c d Jonathan Marcus. "BBC News - Libya: French plane fires on military vehicle". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2011. Cite error: The named reference "bbc.co.uk" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ March 20, 2011 9:24PM. "Italian jet up Tripoli". Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ March 19, 2011 9:24PM. "Operation Ellamy: Designed to strike from air and sea". The Independent. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ March 18, 2011 9:24PM. "Air traffic agency: Libya closes airspace". Herald Sun. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Middle East Unrest | Page 23 | Liveblog live blogging | Reuters.com

- ^ "Libya's Opposition Leadership Comes into Focus". Business Insider. Stratfor. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Rebels Forced from Libyan Oil Port". BBC News. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The battle for Libya: The colonel fights back". The Economist. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi's Military Capabilities". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ "Battle for control rages in Libya - Africa". Al Jazeera English. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Gadhafi Showers Strategic Oil Port with Rockets". Google News. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^

%5b%5bFrench%5d%5d %5b%5bfighter jets%5d%5d

"Battle Rages over Libyan Oil Port". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 3 March 2011.{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Staff writer (2 March 2011). "RT News Line, March 2". RT. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Adams, Richard (10 March 2011). "Libya uprising - Thursday 10 March | World news". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ http://blogs.aljazeera.net/live/africa/libya-live-blog-march-20-0

- ^ a b "Death Toll in Libyan Popular Uprising at 10000". Irib.

- ^ "Time running out for cornered Gaddafi". ABC. 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Libyan attacks could be crime vs humanity: ICC". Reuters. 28 February 2011.

- ^ Casey, Nicholas; de Córdoba, José (26 February 2011). "Where Gadhafi's Name Is Still Gold". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (26 February 2011). "Security Council Calls for War Crimes Inquiry in Libya". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "France Supports Libya Rebel Council". Al Jazeera English. 10 March 2011.

- ^ UN (17 March 2011). "Security Council Authorizes 'All Necessary Measures' To Protect Civilians in Libya". UN News Centre. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "US fires 110 missiles at targets in Libya - World news - Mideast/N. Africa - msnbc.com". MSNBC. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Viscusi, Gregory (23 February 2011). "Qaddafi Is No Mubarak as Regime Overthrow May Trigger a 'Descent to Chaos'". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Whitlock, Craig (22 February 2011). "Gaddafi Is Eccentric But the Firm Master of His Regime, Wikileaks Cables Say". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Silver, Nate (31 January 2011). "Egypt, Oil and Democracy". FiveThirtyEight: Nate Silver's Political Calculus. (blog of The New York Times). Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ali Alayli, Mohammed (4 December 2005). "Resource Rich Countries and Weak Institutions: The Resource Curse Effect" (PDF). Berkeley University. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ More Killed in Libya Crackdown (Television news production). ITN News via YouTube. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Solomon, Andrew (21 February 2011). "How Qaddafi Lost Libya". News Desk (blog of The New Yorker). Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Staff writer (2 March 2009). "Libya's Jobless Rate at 20.7 Percent: Report". Reuters. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b Maleki, Ammar (9 February 2011). "Uprisings in the Region and Ignored Indicators". Payvand.

- ^ Kanbolat, Hasan (22 February 2011). "Educated and Rich Libyans Want Democracy". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results". Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency International. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Endgame in Tripoli – The Bloodiest of the North African Rebellions So Far Leaves Hundreds Dead". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Simons, Geoffrey Leslie (1993). Libya – The Struggle for Survival. St. Martin's Press (New York City). p. 281. ISBN 978-0-312-08997-9.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "A Civil War Beckons – As Muammar Qaddafi Fights Back, Fissures in the Opposition Start To Emerge". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Staff writer (24 February 2011). "The Liberated East – Building a New Libya – Around Benghazi, Muammar Qaddafi's Enemies Have Triumphed". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Shadid, Anthony (18 February 2011). "Libya Protests Build, Showing Revolts' Limits". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ a b Timpane, John (28 February 2011). "Twitter and Other Services Create Cracks in Gadhafi's Media Fortress". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Table (undated). "Freedom of the Press 2009 – Table of Global Press Freedom Rankings" (PDF (696 KB); requires Adobe Reader). Freedom House. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Eljahmi, Mohamed (Winter 2006). "Libya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant". Middle East Quarterly (via Middle East Forum). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Building a New Libya – Around Benghazi, Muammar Qaddafi's Enemies Have Triumphed". The Economist. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Black, Ian (10 April 2007). "Great Grooves and Good Grammar – After Years When Foreign Language Teaching Was Banned, Libyans Are Now Queuing Up To Learn English". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2002). The Middle East and North Africa, 2003. Europa Publications (London). p. 758. ISBN 978-1-85743-132-2.

- ^ Bright, Martin (28 March 2004). "Gadaffi Still Hunts 'Stray Dogs' in UK – Despite Blair Visit, Dissidents Say $1m Bounty Remains on Head of Dictator's Opponent". The Observer. UK (via The Guardian). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Davis, Brian Lee (1990). Qaddafi, Terrorism, and the Origins of the U.S. Attack on Libya. Praeger Publishing (New York City). ISBN 978-0-275-93302-9.

- ^ Staff writer (4 February 2011). "Calls for Weekend Protests in Syria – Social Media Used in Bid To Mobilise Syrians for Rallies Demanding Freedom, Human Rights and the End to Emergency Law". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Debono, James (9 February 2011). "Libyan Opposition Declares 'Day of Rage' Against Gaddafi". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Landay, Janathan S.; Strobel, Warren P.; Ibrahim, Arwa (18 February 2011). "Violent Repression of Protests Rocks Libya, Bahrain, Yemen". McClatchy Newspapers. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siddique, Haroon; Owen, Paul; Gabbat, Adam (17 February 2011). "Bahrain in Crisis and Middle East Protests – Live Blog". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Staff writer (16 January 2011). "Libyans Protest over Delayed Subsidized Housing Units". Almasry Alyoum. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Abdel-Baky, Mohamed (16 January 2011). "Libya Protest over Housing Enters Its Third Day – Frustrations over Corruption and Incompetence in Government Housing Schemes for Poor Families Spills over into Protests across the Country". Al-Ahram (via mesop.de). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (4 February 2011). "Watchdog Urges Libya To Stop Blocking Websites". Agence France-Press e]] (via Google News). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 January 2011). "Libya Sets Up $24 Bln Fund for Housing". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (8 February 2011). "Libyan Writer Detained Following Protest Call". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahmoud, Khaled (9 February 2011). "Gaddafi Ready for Libya's 'Day of Rage'". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "New Media Emerge in 'Liberated' Libya". BBC News. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "Evidence of Libya Torture Emerges – As the Opposition Roots Through Prisons, Fresh Evidence Emerges of the Government's Use of Torture". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Gillis, Clare Morgana (4 March 2011). "In Eastern Libya, Defectors and Volunteers Build Rebel Army". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Golovnina, Maria (28 February 2011). "World Raises Pressure on Gaddafi". National Post. Canada. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya Opposition Launches Council – Protesters in Benghazi Form a National Council 'To Give the Revolution a Face'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim (11 March 2011). "Why Won't You Help, Libyan Rebels Ask West". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (undated). "The Council's Statement". National Transitional Council. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libyan Ex-Minister Wants Election". Sky News Business Channel. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Williams, Davis; Greenhill, Sam (25 February 2011). "Now Gaddafi Blames Hallucinogenic Pills Mixed with Nescafe and bin Laden for Uprisings... Before Ordering Bloody Hit on a Mosque". Daily Mail. UK. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Millership, Peter; Blair, Edmund (24 February 2011). "Gaddafi Says Protesters Are on Hallucinogenic Drugs". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ al-Atrush, Samer (24 February 2011). "Kadhafi Says Al-Qaeda Behind Insurrection". Agence France-Press e]] (via Yahoo! News). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Ben Gedalyahu, Tzvi (2 March 2011). "Yemen Blames Israel and US; Qaddafi Accuses US – and al-Qaeda". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (9 March 2011). "Gadhafi: US, Britain, France Conspiring To Control Libya Oil – Spokesman for Rebel National Libyan Council Says Victory Against Libya's Longtime Leader Will Only Come When Rebels Get a No-Fly Zone, an Issue That Western Nations Are Seriously Debating". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Libya: 'More Than 1,000 Dead'". The Telegraph. 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi: 'I Will Not Give Up', 'We Will Chase the Cockroaches'". The Times. 22 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Three Scenarios for End of Gaddafi: Psychologist". Al Arabiya. 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Warns of al-Qaeda Spread 'Up to Israel'". Al Arabiya.

- ^ "Libya Fights Protesters with Snipers, Grenades". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya Witness: 'It's Time for Revolt. We Are Free'". Euronews. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Williams, Jon (19 February 2011). "The Editors: The Difficulty of Reporting from Inside Libya". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Muammar al-Gaddafi is Accused of Hiring Soldiers from Chad, Dozens of People Dead in Benghazi". WNCNews. 18 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Has Gaddafi unleashed a mercenary force on Libya?". guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ David Smith in Johannesburg. "Has Gaddafi unleashed a mercenary force on Libya? | World news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kenya: 'Dogs of War' Fighting for Gaddafi". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Zimbabwean army helping Gaddafi in Libya". Thezimbabwean.co.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Pedja Obradovic. "Belgrade Denies Serbian Planes Bombed Libya Protesters". Balkaninsight.com. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Live Blog - Libya Feb 25". blogs.aljazeera.net. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Muammar Gaddafi Ordered Lockerbie Bombing, Says Libyan Minister". News Limited. Retrieved 17 March 2011. – citing an original interview with Expressen in Sweden: Julander, Oscar; Hamadé, Kassem (23 February 2011). "Khadaffi gav order om Lockerbie-attentatet". Expressen (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) English translation (via Google Translate). - ^ a b c Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Pressure Mounts on Isolated Gaddafi". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Dziadosz, Alexander (23 February 2011). "Benghazi, Cradle of Revolt, Condemns Gaddafi". Reuters (via The Star). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

The eastern city of Benghazi... was alive with celebration on Wednesday with thousands out on the streets, setting off fireworks

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Gaddafi Loses More Libyan Cities – Protesters Wrest Control of More Cities as Unrest Sweeps African Nation Despite Muammar Gaddafi's Threat of Crackdown". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Protesters Defy Gaddafi as International Pressure Mounts (1st Lead)". Deutsche Presse-Agentur (via Monsters and Critics). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Middle Eastern Media See End of Gaddafi". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (16 March 2011). "Civil War in Libya". CNN. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (10 March 20110). "Libya's Zawiyah Back under Kadhafi Control: Witness". Agence France-Press e]] (via Google News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff writer (11 March 2011). "Gaddafi Loyalists Launch Offensive – Rebel Fighters Hold Only Isolated Pockets of Oil Town after Forces Loyal to Libyan Leader Attack by Air, Land and Sea". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (18 March 2011). "Libya: UN Backs Action Against Colonel Gaddafi". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ BBC News - Live: Libya crisis. BBC News.

- ^ Staff writer (18 March 2011). "Libya Declares Ceasefire But Fighting Goes On". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Gaddafi Defiant as State Teeters – Libyan Leader Vows To 'Fight On' as His Government Loses Control of Key Parts in the Country and as Top Officials Quit". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Middle East and North Africa Unrest". BBC News. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Free Press Debuts in Benghazi". Magharebia. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Libya Protests: Gaddafi Embattled by Opposition Gains". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Sherwell, Philip (6 March 2011). "Libya's Bloody Rebellion Turns into Civil War – Fighting Leaves 30 Dead as Tanks Shell Houses and Snipers Shoot at Everyone on the Streets". Irish Independent. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "World Powers Edge Closer to Gadhafi Solution". Agence France-Press e]] (via The Vancouver Sun). Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Ghaddafi's Control Reduced to Part of Tripoli". afrol News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Robertson, Delia (1 March 2011). "Experts Disagree on African Mercenaries in Libya". Voice of America. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ The Sun

- ^ Staff writer (18 March 2011). "Libya Live Blog – March 19". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Amara, Tarek; Karouny, Mariam (18 March 2011). "Gaddafi Forces Shell West Libya's Misrata, 25 Dead". Reuters. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (19 March 2011). "Libya: Gaddafi Forces Attacking Rebel-Held Benghazi". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ 19 March 2011, Gaddafi forces encroaching on Benghazi. Al Jazeera English.

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8393237/Libya-moment-a-rebel-jet-crashed-to-earth-in-flames.html

- ^ http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/03/201131934914112208.html

- ^ Daily Telegraph

- ^ Xinhuanet

- ^ Al Jazeera

- ^ "Plane shot down over rebel-held city in Libya |myFOXlubbock | FOX 34 News KJTV Lubbock, Texas". myFOXlubbock. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.myfoxlubbock.com/news/world/story/Plane-shot-down-over-rebel-held-city-in-Libya/9x2_eMAtKU6TqK6LILL-rw.cspx

- ^ "Fighter plane shot down in Libya's Benghazi: Al-Jazeera". News.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "French jets open fire on Libyan military vehicle". CNN. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Helene Fouquet (19 March 2011). "French Jet Shoots, 'Neutralizes' Libyan Military Vehicle". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "US Launches Missile Strike in Libya". The World Reporter. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ a b Live: Libya Crisis BBC News, 19 March 2011 Template:WebCite

- ^ "U.S. Launches Cruise Missiles Against Qaddafi's Air Defenses". Fox News Channel. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "West pounds Libya with air strikes, Tomahawks". News.smh.com.au. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Airstrikes begin on Libya targets - Africa". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Crisis in Libya: U.S. bombs Qaddafi's airfields". CBS News.

- ^ "French and American planes over Libya".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help); Text "http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/world-africa-12800635" ignored (help) - ^ "Libye/avion abattu: la France dément". Lefigaro.fr. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.monstersandcritics.com/news/africa/news/article_1627376.php/British-jets-fired-on-Libyan-targets

- ^ http://news.blogs.cnn.com/2011/03/19/libya-live-blog-gadhafi-to-obama-sarkozy-butt-out/?hpt=T1

- ^ 10:46pm The Pentagon said it had lost no aircraft in the first day of attacks on Libya -and "questions all statements" from Gaddafi - including his offer of a ceasefire.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Libya's Humanitarian Crisis – As Protests Continue, Medical Supplies, Along with Fuel and Food, Are Running Dangerously Short". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (25 February 2011). "Libya: ICRC Launches Emergency Appeal as Humanitarian Situation Deteriorates". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (2 March 2011). "Libya: Poor Access Still Hampers Medical Aid to West". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Live Update: Thousands Flee Across Libya-Tunisia Border". The Globe and Mail. Canada. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Saunders, Doug (1 March 2011). "At a Tense Border Crossing, a Systematic Effort To Keep Black Africans Out". The Globe and Mail. Canada. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ (registration required) Sayar, Scott; Cowell, Alan (3 March 2011). Libyan Refugee Crisis Called a 'Logistical Nightmare'". The New York Times.

- ^ Staff writer (8 March 2011). "Statistics of IOM Operations in Egypt – 8 March 2011". UN – Egypt. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Live Blog ¿ Libya Feb 22". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "At Least 3,000 Dead in Libya: Rights Group". Indo-Asian News Service (via Sify News). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ http://blogs.aljazeera.net/live/africa/libya-live-blog-march-20-0

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libya Justice Minister Resigns To Protest 'Excessive Use of Force' Against Protesters – Ambassadors to the Arab League, India and China Have Also Stepped Down To Voice Dissent with the Government, as Violent Clashes Spill into Seventh Day". Reuters (via Haaretz). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Staff writer (17 February 2011). "Live Blog – Libya". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Libya: Obama Seeks Consensus on Response to Violence". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libya's Ambassadors to India, Arab League Resign in Protest Against Government". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libyan Diplomat in China Resigns over Unrest: Report". Agence France-Press e]] (via Google News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Almasri, Mohammed (21 February 2011). "Libyan Ambassador to Belgium, Head of Mission to EU Resigns". Global Arab Network. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libya's Ambassador to India Resigns in Protest Against Violence: BBC". Reuters (via Daily News and Analysis). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer. "Western Nations Urge Security Council To Demand Immediate End to Libyan Crackdown on Civilians". Associated Press (via Google News). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Maharaj, Davan (21 February 2011). "Libya: UN Diplomats Resign in Protest". Babylon & Beyond (blog of the Los Angeles Times). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Staff writer (11 March 2011). "Libya's Arabian Gulf Oil Co Hopes To Fund Rebels Via Crude Sales-FT". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "N. Africa, Mideast Protests – Gadhafi: I'm Still Here". This Just In (blog of CNN). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (22 February 2011). "Libya: Warship Defects to Malta". Babylon & Beyond (blog of the Los Angeles Times). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Update 1-Libyan Islamic Leaders Urge Muslims To Rebel". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b Hussein, Mohammed (21 February 2011). "Libya Crisis: What Role Do Tribal Loyalties Play?". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Gaddafi Aide 'To Talk to Rivals' – Move Comes as Deputy Foreign Minister Says the Government Could Use Force If 'All Other Attempts Are Exhausted'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Building a New Libya – Around Benghazi, Muammar Qaddafi's Enemies Have Triumphed". The Economist. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Salama, Vivian (22 February 2011). "Libya's Crown Prince Says Protesters Will Defy 'Brutal Forces'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ [dead link] "Gaddafi Nears His End, Exiled Libyan Prince Says". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 24 February 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Libya's 'Crown Prince' Makes Appeal – Muhammad al-Senussi Calls for the International Community To Help Remove Muammar Gaddafi from Power". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (9 March 2011). "Libya's 'Exiled Prince' Urges World Action". Agence France-Press e]] (via Khaleej Times). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Cynthia (9 March 2011). "Libyan Crown Prince Urges No-Fly Zone, Air Strikes". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "EL SENUSSI: The Libyan Tea Party". The Washington Times. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ [clarification needed] Staff writer (16 February 2011). "Libia, principe Idris: "Gheddafi assecondi popolo o il Paese finirà in fiamme"". Adnkronos (in Italian). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help) - ^ Krakauer, Steve (21 February 2011). "Who Is Moammer Gadhafi? Piers Morgan Explores the Man at the Center of Libya's Uprising". Piers Morgan Tonight (blog of Piers Morgan Tonight via CNN). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Libyan Royal Family Seeking Swedish Asylum". Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå (via Stockholm News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Libya Live Report". Agence France-Press e]] (via Yahoo! News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Varas, Arturo (25 February 2011). "Chavez Joins Ortega and Castro To Support Gaddafi". Ecuador Times. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Cárdenas, José R. (24 February 2011). "Libya's Relationship Folly with Latin America". Shadow Government (blog of Foreign Policy). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Babington, Deepa (20 February 2011). "Berlusconi Under Fire for Not 'Disturbing' Gaddafi". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "As It Happened: Mid-East and North Africa Protests". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Perry, Tom (21 February 2011). "Arab League 'Deeply Concerned' by Libya Violence". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Galal, Ola (22 February 2011). "Arab League Bars Libya From Meetings, Citing Forces' 'Crimes'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "Libya Suspended from Rights Body – United Nations General Assembly Unanimously Suspends Country from UN Human Rights Council, Citing 'Rights Violations'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "UN Security Council Slaps Sanctions on Libya – Resolution Also Calls for War Crimes Inquiry Over Deadly Crackdown on Protesters". MSNBC. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (4 March 2011). "File No.: 2011/108/OS/CCC" (PDF format (183 KB); requires Adobe Reader). Interpol. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Gaddafi Sees Global Assets Frozen – Nations Around the World Move To Block Billions of Dollars Worth of Assets Belonging to Libyan Leader and His Family". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (8 March 2011). "Joint Statement of the Joint Ministerial Meeting of the Strategic Dialogue Between the Countries of the Cooperation Council for the Arab Gulf States and Australia" (in Arabic; Google Translate translation). Gulf Cooperation Council. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (12 March 2011). "Arab League Backs Libya No-Fly Zone". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "Libya Protests: Evacuation of Foreigners Continues". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "China's Libya Evacuation Highlights People-First Nature of Government". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ a b Staff writer (3 March 2011). "35,860 Chinese Nationals in Libya Evacuated: FM". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Krishnan, Ananth (28 February 2011). "Libya Evacuation, a Reflection of China's Growing Military Strength". The Hindu. India. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "Evacuees Arrive in Grand Harbour, Speak of Their Experiences – Smooth Welcoming Operation". The Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Greek Ferry Brings More Libya Workers to Malta". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Another Ferry, Frigate Arrive with More Workers". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.focus-news.net/?id=n1495467

- ^ Staff writer (10 March 2011). "Mission Libya". The Telegraph. Kolkota, India. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Hacaoglu, Selcan; Giles, Ciaran (23 February 2011). "Americans, Turks Among the Thousands Fleeing Libya". Associated Press (via KFSN-TV). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "Department Defends Libyan Evacuation". The Irish Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Foreigners in Libya". The Globe and Mail. Canada. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya: Maltese Wishing To Stay Urged To Change Their Mind". The Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search? q=cache:KA86UcQALbQJ:www.speroforum.com/a/49106/Tajikistan-Seeks-Russian-Help-To-Evacuate-Citizens-From-Libya+tajikistan+reaction+to+Libya+crisis&cd=10&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk&source=www.google.co.uk

- ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Libya Unrest: UK Plans To Charter Plane for Britons". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Britons Flee Libya on Navy Frigate Bound for Malta". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "RAF Hercules Planes Rescue 150 from Libya Desert". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "35,860 Chinese Nationals Evacuated from Unrest-Torned Libya". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "S. Korean Warship Changes Libyan Destination to Tripoli". Yonhap. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "HMS York Delivers Humanitarian Aid to Benghazi". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Powell, Michael (4 March 2011). "HMS Westminster To Take Over Libyan Duties from HMS York". The News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "Government Announces $5M in Humanitarian Aid to Libya". CTV News Channel. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "RAF Hercules Planes Rescue 150 from Libya Desert". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya: British Special Forces Rescue More Civilians from Desert". Daily Mirror. UK. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Helm, Toby; Townsend, Mark; Harris, Paul (26 February 2011). "Libya: Daring SAS Mission Rescues Britons and Others from Desert – RAF Hercules Fly More Than 150 Oil Workers to Malta – But Up to 500 Still Stranded in Compounds". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [clarification needed] Gebauer, Matthias (28 February 2011). "Riskante Rettungsmission hinter feindlichen Linien". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ [clarification needed] Baldauf, Angi (27 February 2011). "So verlief die spektakuläre Rettungs-Aktion in Libyen – 133 EU-Bürger durch Luftwaffe gerettet – Fallschirmjäger sicherten die Aktion – UN beschliessen Sanktionen gegen Gaddafi". Bild (in German). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Three Dutch marines captured during rescue in Libya". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "3 Dutch Soldiers Captured in Libya". South African Press Association. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (11 March 2011). "Libya: Dutch Helicopter Crew Freed". BBC New. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Davis, Gaye (2 March 2011). "Libya Heading for Civil War – Dangor". Independent Online. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Gadaffi Accepts Chavez's Mediation Offer". Indo-Asian News Service (via The Hindustan Times). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Chavez Libya Talks Offer Rejected – United States, France and Opposition Activists Dismiss Venezuelan Proposal To Form a Commission To Mediate Crisis". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "The Arab revolution: Of rocks and hard places". The Guardian. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ [clarification needed] Staff writer (18 March 2011). "Belgische politici unaniem achter militaire interventie - Onrust in het Midden-Oosten" (in Flemish). De Morgen. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (17 March 2011). "CF-18 Jets To Help Enforce Libya No-Fly Zone". CBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (15 March 2011)"F-16s Readied To Defend Libyan People". The Copenhagen Post. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ [clarification needed] Staff writer (18 March 2011). "France: Military Action To Take Place 'Swiftly' Against Libya". CNN.

- ^ [clarification needed] Αλατζάς, Κώστας (18 March 2011). "Ο ρόλος της Ελλάδας στο ενδεχόμενο επέμβασης στη Λιβύη" (in Greek). Skai News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ News.yahoo.com, Yahoo News.

- ^ a b c Kirka, Danica; Lawless, Jill (18 March 2011). "Amid Uncertainty, Allies Prepare for No-Fly Zone. Associated Press (via Forbes). Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (18 March 2011). "Netherlands Willing To Contribute to Libya Intervention – PM". Dow Jones Newswires (via NASDAQ). Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ [clarification needed] Nordberg, Marianne. "Norge vil delta i angrep i Libya – Norge kommer til å delta hvis utenlandske styrker angriper i Libya. Det sier forsvarsminister Grete Faremo" Template:No icon Klar Tale. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Mangasarian, Leon; Fam, Mariam (19 March 2011). "Qaddafi’s Forces Defy Cease-Fire, Attack Rebels in Benghazi". Bloomberg (via Bloomberg Businessweek). Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "BBC Live Parliamentary Broadcast, 18 March 2011". BBC News.

- ^ "Remarks by the President on the Situation in Libya, 18 March 2011".

- ^ Macdonald, Alistair (1 March 2011). "Cameron Doesn't Rule Out Military Force for Libya" (Abstract; (subscription required) for full article). The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Pullella, Philip (7 March 2011). "Italy Tiptoes on Libya Due to Energy, Trade, Migrants". Reuters (via MSNBC). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ (registration required) Singer, David E.; Shanker, Thom (2 March 2011). "Gates Warns of Risks of a No-Flight Zone". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [dead link] "Russian FM Knocks Down No-Fly Zone for Libya". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Usborne, David (2 March 2011). "Russia Slams 'No-Fly Zone' Plan as Cracks Appear in Libya Strategy". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "China Voices Misgivings About Libya 'No-Fly' Zone Plan". Reuters (via AlertNet). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Craig (3 March 2011). "Libyan No-Fly Zone Would Be Risky, Provocative". CNN. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Shrivastava, Sanskar (14 March 2011). "Nations Oppose Military Intervention in Libya". The World Reporter. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Rogin, Josh (7 March 2011). "US Ambassador to NATO: No-Fly Zone Wouldn't Help Much". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Donnet, Pierre-Antoine (7 March 2011). "Britain, France Ready Libya No-Fly Zone Resolution". Agence France-Press e]] (via Google News]). Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (14 March 2011). "Libyan Rebels Urge West To Assassinate Gaddafi as His Forces Near Benghazi – Appeal To Be Made as G8 Foreign Ministers Consider Whether To Back French and British Calls for a No-Fly Zone over Libya". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Lederer, Edith M. (17 March 2011). "Libya No-Fly Zone Approved By UN Security Council". Associated Press (via The Huffington Post). Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (17 March 2011). "Security Council Authorizes 'All Necessary Measures' To Protect Civilians in Libya". UN News Centre. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (17 March 2011). "UN Security Council Resolution on Libya – Full Text – Read the Full Text of the Resolution Passed at UN Headquarters in Favour of a No-Fly Zone and Air Strikes Against Muammar Gaddafi". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ "Video, Libya: Ceasefire Defended As Tornados Head To Libya Amid No-Fly Zone Resolution | World News | Sky News". News.sky.com. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Varner, Bill (2 March 2011). "China Joins Russia in Signaling Potential Opposition to Libya No-Fly Zone". Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Itar-Tass". Itar-Tass. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "India, China, Russia oppose air strikes on Libya". Deccan Herald. The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

Further reading

- Pargeter, Alison (2006). "Libya: Reforming the impossible?". Review of African Political Economy. 33 (108): 219–35. doi:10.1080/03056240600842685.

- Sadikia, Larbi (2010). "Wither Arab 'Republicanism'? The Rise of Family Rule and the 'End of Democratization' in Egypt, Libya and Yemen". Mediterranean Politics. 15 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1080/13629391003644827.

External links

- Collected news coverage

- "Libya Uprising". Al Jazeera English.

- "Live Blog". Al Jazeera English.

- "Libya Revolt". BBC News.

- "Libya in Crisis". The Guardian. UK.

- "Libya –The Protests (2011)". The New York Times.

- "Libya". Reuters.

- "Libya 2011". RIA Novosti.

- "Libya". Der Spiegel.

- Articles

- "A Call To Defend Libya's Unity, Sovereignty, and Independence from Imperialist Aggression". Free Arab Voice.

- "Libya 2007–2010 Data, 23 Indicators Related to Peace, Democracy and Other Aspects". Vision of Humanity.

- Clark, Campbell; Chase, Steven (1 March 2011). "Canada Girds for Substantial Military Role in North Africa". The Globe and Mail. Canada. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from March 2011

- Current events from March 2011

- Use dmy dates from February 2011

- 2011 Libyan uprising

- Wars involving Libya

- 2010–2011 Arab world protests

- 2011 in Libya

- Conflicts in 2011

- Protests in Libya

- 21st-century conflicts

- Politics of Libya

- History of Libya

- Military history of Libya

- Libyan society

- Guerrilla wars

- Riots and civil unrest in Libya

- Counter-terrorism in Libya

- Rebellions in Africa