Thessaloniki

Template:Infobox Thessaloniki Thessaloniki (Template:Lang-el, IPA: [θesaloˈnici]), historically also known as Thessalonica or Salonica, is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of the periphery of Central Macedonia as well as the de facto capital of the Greek region of Macedonia. Its honorific title is Συμπρωτεύουσα (Symprotévousa), literally "co-capital", a reference to its historical status as the Συμβασιλεύουσα (Symvasilévousa) or "co-reigning" city of the Byzantine Empire, alongside Constantinople. According to the 2001 census, the municipality of Thessaloniki had a population of 363,987, while its Urban Area had a population of 773,180. The Larger Urban Zone (LUZ) of Thessaloniki has an estimated 995,766 residents (2004), while its area is 1,455.62km².[1]

Thessaloniki is Greece's second major economic, industrial, commercial and political centre, and a major transportation hub for the rest of southeastern Europe; its commercial port is also of great importance for Greece and the southeastern European hinterland. The city is renowned for its events and festivals, the most famous of which include the annual International Trade Fair, the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, and the largest bi-annual meeting of the Greek diaspora.[2]

Thessaloniki is considered northern Greece's cultural and educational centre. It is home to numerous notable Byzantine monuments, including the Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments of Thessalonika, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as several Ottoman and Sephardic Jewish structures. The city's main university, Aristotle University, is the largest in Greece and ranked among the best 250 universities in Europe.[3]

Etymology

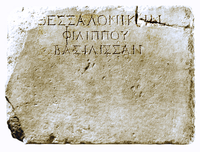

All variations for the city's name derive from the original (and current) appellation in Greek: Θεσσαλονίκη, literally translating to "Thessalian Victory" and in origin the name of a princess, Thessalonike of Macedon, who was so named because she was born on the day of the Macedonian victory at the Battle of Crocus Field.[4] The alternative name Salonika, formerly the common name used in some western European languages, is derived from a variant form Σαλονίκη (Saloníki) in popular Greek speech. The city's name is also rendered Thessaloníki or Saloníki with a dark l typical of Macedonian Greek.[5][6]

Names in other languages prominent in the city's history include סלוניקה (Salonika) in Ladino, سلانيك (Selânik) in Ottoman Turkish, Солун (Solun) in the South Slavic languages and Sãrunã in Aromanian. It is sometimes abbreviated to Thess by Anglophone Greeks of the diaspora and by the troops of the international forces stationed in the various ex-Yugoslav territories who visit the city for their breaks from duty.

History

Antiquity

The city was founded around 315 BC by the King Cassander of Macedon, on or near the site of the ancient town of Therma and 26 other local villages.[7] He named it after his wife Thessalonike, a half-sister of Alexander the Great (Thessalo-nikē meaning "Thessalian Victory")[8] (See Battle of Crocus field). Under the kingdom of Macedon the city retained its own autonomy and parliament.

After the fall of the kingdom of Macedon in 168 BC, Thessalonica became a city of the Roman Republic. It grew to be an important trade-hub located on the Via Egnatia,[9] the road connecting Dyrrhachium and Constantinople which facilitated trade between Europe and Asia. The city became the capital of one of the four Roman districts of Macedonia.[9] Later, and because of the city's importance in the Balkan peninsula, it became the capital of all the Greek provinces of the Roman Empire. In 379 when the Roman Prefecture of Illyricum was divided between the East and West Roman Empires, Thessaloniki became the capital of the new Prefecture of Illyricum.[9]

Medieval times

The economic expansion of the city continued through the 12th century as the rule of the Komnenoi emperors expanded Byzantine control to the north. Thessaloniki passed out of Byzantine hands in 1204, when Constantinople was captured by the forces of the Fourth Crusadeand incorporated the city and its surrounding territories in the Kingdom of Thessalonica — which then became the largest vassal of the Latin Empire. In 1224, the Latin kingdom was overrun by the Despotate of Epirus and several years later, the Epirote ruler Theodore Komnenos Doukas crowned himself Byzantine emperor in the city. Following his defeat at Klokotnitsa however in 1230, the Kingdom of Thessalonica became a vassal state of the Second Bulgarian Empire but was again recovered in 1246, this time by the Nicaean Empire. In the 1340s, the city was the scene of an anti-aristocratic Commune of the Zealots.

In 1423, Despot Andronicus, who was in charge of the city, ceded it to the Republic of Venice in the hope that it could be protected from the Ottomans who were besieging the city (there is no evidence to support the oft-repeated story that he sold the city to them). The Venetians held Thessaloniki until it was captured by the Ottoman Sultan Murad II on the 29th of March, 1430.[12]

Ottoman period

Murad II took Thessaloniki with a brutal massacre[13] and enslaved roughly one-fifth of the city's native population.[14] Upon the capture and plunder of Thessaloniki, many of its inhabitants escaped,[15] including intellectuals such as Theodorus Gaza “Thessalonicensis” and Andronicus Callistus.[16]

During the Ottoman period, the city's Muslim and Jewish population grew. By 1478 Selânik (سلانیك), as the city came to be known in Ottoman Turkish, had a population of 4,320 Muslims, 6,094 Greek Orthodox and some Catholics, but no Jews. Soon after the turn of the 16th century, nearly 20,000 Sephardic Jews had immigrated to Greece from Spain following their expulsion.[13] By ca. 1500, the numbers had grown to 7,986 Greeks, 8,575 Muslims, and 3,770 Jews. By 1519, Sephardic Jews numbered 15,715, 54% of the city's population. Some historians consider the Ottoman regime's invitation to the Jews was a strategy to prevent the ethnic Greek population (Eastern Orthodox Christians) from dominating the city.[17]

Selanik was a sanjak capital in Rumeli Eyaleti (Balkans) until 1826, and subsequently the capital of Selanik Vilayeti (between 1826 and 1864 Selanik Eyaleti). This consisted of the sanjaks of Selanik, Serres and Drama between 1826 and 1912.[citation needed] Thessaloniki was also a Janissary stronghold where novice Janissaries were trained. In June 1826, regular Ottoman soldiers attacked and destroyed the Janissary bases, an event known as The Auspicious Incident in Ottoman history. From 1870, driven by economic growth, the city's population expanded by 70%, reaching 135,000 in 1917.[citation needed]

20th century

During the First Balkan War, on 26 October 1912 (Old Style), the feast day of the city's patron saint, Saint Demetrius, the Greek Army accepted the surrender of the Ottoman garrison at Thessalonika; after the Second Balkan War, Thessalonika was annexed to Greece by the Treaty of Bucharest (1913).

In 1915, during World War I, a large Allied expeditionary force established a base at Thessaloniki for operations against pro-German Bulgaria. This culminated in the establishment of the Macedonian or Salonika Front.[18] In 1916, pro-Venizelist Greek army officers and civilians, with the support of the Allies, launched the Movement of National Defence,[19] creating a pro-Allied temporary government that controlled northern Greece and the Aegean, against the official government of the King in Athens. The city was dubbed by supporters as symprotévousa ("co-capital").[citation needed]

Most of the old center of the city was destroyed by the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, which started accidentally by an unattended kitchen fire on the 18th of August 1917.[20] The fire swept through the centre of the city, leaving 72,000 people homeless; according to the Pallis Report, most of them were Jewish (50,000). As many businesses were destroyed, it resulted to 70% of the population being unemployed, while also a number of religious structures of the three major faiths were lost. Nearly one-quarter of the total population of approximately 271,157 became homeless. Following the fire the government prohibited quick rebuilding, so it could implement the new redesign of the city according to the European-style urban plan prepared by French architect Ernest Hébrard. Because of their losses and unable to wait for the rebuilding of the new plan, nearly half of the Jewish Greek population emigrated to France, the United States and Palestine.

After the defeat of Greece in the Greco-Turkish War and during the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, Greeks were expelled from Turkey and many refugees came to Thessaloniki. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in the city, changing its demographics. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city's population. During the interwar period, Greece granted Jews full civil rights, the same as all other Greek citizens.[21]

During World War II, Thessaloniki fell to the forces of Nazi Germany on April 22, 1941 and remained under German occupation until October 30, 1944 when it was liberated by the Greek People's Liberation Army. The Nazis soon forced the Jews into a ghetto near the railroads and in 1943 began deportation of 50,000 of the city's Jews (95% of the Jewish population) to its concentration camps. They deported and killed 50,000 of the city's Jews in concentration camps, where most were murdered in the gas chambers.[22] The Germans also deported 11,000 Jews to forced labor camps, where most perished.[22] The city suffered considerable damage from Allied bombing as they began to move against the Germans. Only 1200 Jews live in the city today.

After the war, Thessaloniki was rebuilt with large-scale development of new infrastructure and industry throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Many of its architectural treasures still remain, adding value to the city a tourist destination. Several early Christian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki were added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988.

Thessaloniki was celebrated as the European Capital of Culture in 1997, when it sponsored events across the city and region. In 2004 the city hosted a number of the football (soccer) events as part of the 2004 Summer Olympics.

Environment

Geology

Thessaloniki was hit by strong earthquakes in 620, 667, 700, 1677, 1759, 1902, 1904, 1905 and 1932[citation needed]. On 19–20 June 1978, the city suffered a series of powerful earthquakes, registering 5.5 and 6.5 on the Richter scale.[23][24] The tremor caused considerable damage to several buildings and ancient monuments, but the city withstood the catastrophy without any major problems.[24] One apartment building in central Thessaloniki collapsed during the second earthquake, killing many, raising the final death toll to 36.[24]

Climate

Thessaloniki lies on the northern fringe of the Thermaic Gulf, on its eastern side. The city has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification "Csa") that borders on an semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification "BSk" or "BSh" depending on the system used) with annual average precipitation of 460 mm. Snowfalls are sporadic, but happen more or less every year.

The city lies in a transitional climatic zone, so its climate displays characteristics of continental and Mediterranean climates. Winters are relatively dry, with common morning frost. Snowfalls occur almost every year, but usually the snow does not stay for more than a few days. During the coldest winters, temperatures can drop to −10C°/14F (Record min. -14C°/7F).[citation needed]

Thessaloniki's summers are hot with rather humid nights. Maximum temperatures usually rise above 30C°/86F, but rarely go over 40C°/104F (Record max. 44C).[citation needed] Rain is seldom in summer, and mainly falls during thunderstorms.

| Climate data for Thessaloniki | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

20.38 (68.68) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

15.06 (59.11) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

9.69 (49.44) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.8 (1.45) |

38.0 (1.50) |

40.6 (1.60) |

37.5 (1.48) |

44.4 (1.75) |

29.6 (1.17) |

23.9 (0.94) |

20.4 (0.80) |

27.4 (1.08) |

40.8 (1.61) |

54.4 (2.14) |

54.9 (2.16) |

448.7 (17.67) |

| Average precipitation days | 11 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 96 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 124 | 140 | 155 | 240 | 279 | 300 | 372 | 341 | 240 | 186 | 120 | 120 | 2,620 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[25] BBC weather[26] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture in Thessaloniki is the direct result of the city's position at the centre of all historical developments in the Balkans. Aside from its commercial importance, Thessaloniki was also for many centuries, the military and administrative hub of the region, and beyond this the transportation link between Europe and the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel / Palestine). Merchants, traders and refugees from all over Europe settled in the city. The need for commercial and public buildings in this new era of prosperity led to the construction of large edifices in the city centre. During this time, the city saw the building of banks, large hotels, theatres, warehouses, and factories.

The city layout changed after 1870, when the seaside fortifications gave way to extensive piers, and many of the oldest walls of the city were demolished, including those surrounding the White Tower.[citation needed] As parts of the early Byzantine walls were demolished, this allowed the city to expand east and west along the coast.

The expansion of Eleftherias Square towards the sea completed the new commercial hub of the city and at the time was considered one of the most vibrant squares of the city. As the city grew, workers moved to the western districts, due to their proximity near factories and industrial activities; while the middle and upper classes gradually moved from the city-centre to the eastern suburbs, leaving mainly businesses. In 1917, a devastating fire swept through the city and burned uncontrollably for 32 hours.[27] It destroyed the city's historic centre and a large part of its architectural heritage, but paved way for many modern buildings and changed the city into a thriving European city centre.

Kentro - City Centre

After the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, a team of architects and urban planners including Thomas Mawson and Ernest Hebrard, a French architect, chose the Byzantine era as the basis of their (re)building designs for Thessaloniki’s city centre. The new city plan included axes, diagonal streets and monumental squares, with a street grid that would channel traffic smoothly. The plan of 1917 included provisions for future population expansions and a street and road network that would be, and still is sufficient today.[27] It contained sites for public buildings and provided for the restoration of Byzantine churches and Ottoman mosques.

Today the city center of Thessaloniki includes the features designed as part of the plan and forms the point in the city where most of the public buildings, historical sites, entertainment venues and stores are located. The centre is characterized by its many historical buildings, arcades, laneways and distinct architectural styles such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco which can be seen on many of its buildings.

The city centre, or as its also called the historic center is divided into several districts, of which include Ladadika (where many entertainment venues and tavernas are located), Kapani (where the central city market is located), Diagonios, Nauarinou, Rotonta, Agia Sofia and Ippodromio (white tower), which are all located around Thessaloniki’s most central point, Aristotelous Square.

The west point of the city centre is home to Thessaloniki's law courts, its central international railway station and the port, while on its eastern side stands the city’s two universities, the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre, the city’s main stadium, its archaeological and Byzantine museums, the new city hall and its central parklands and gardens, namely those of the Palios Zoologikos Kipos and Pedio tou Areos. The central road arteries that pass through the city centre, designed in the Ernest Herbrard plan, include those of Tsimiski, Egnatia, Nikis, Mitropoleos, Venizelou and St. Dimitrius avenues.

Ano Poli

Ano Poli (also called Old Town) is the heritage listed district north of Thessaloniki’s city centre that was saved from the great fire of 1917 and was declared a UNESCO heritage site by ministerial actions of Melina Merkouri, during the 1980’s. It consists of Thessaloniki’s most traditional part of the city, still featuring small stone paved streets, old squares and homes featuring old Macedonian and Ottoman architecture.

Ano Poli also, meaning ‘upper city’, is the highest point in Thessaloniki and as such, is the location of the city’s acropolis and its Byzantine fort, the Heptapyrgion and the city's remaining walls, with many of its additional Ottoman and Byzantine structures still standing. The area provides access to the Seich Sou forest national park and provides amphitheatric views of the whole city and the Thermaic gulf.

Southeastern Thessaloniki

Southeastern Thessaloniki up until the 1920’s was home to the city’s most affluent residents and formed the outermost suburbs of the city at the time, with the area close to the Thermaic gulf coast called Exoches, meaning ‘the countryside’. Today southeastern Thessaloniki has in someway become a natural extension of the city center, with the wide avenues of Megalou Alexandrou, Georgiou Papandreou (Antheon), Vasilisis Olgas, Delfon, Konstantinou Karamanli (Egnatia) and Charilaou passing through it; and the area extending to Kalamaria and Pylaia, about 9km from the White Tower in the city centre.

Southeastern Thessaloniki is characterized by is modern architecture and apartment buildings, home to the middle-class and more than half of the municipality of Thessaloniki population. Today this area of the city is also home to 3 of the city’s main football stadiums, the Thessaloniki concert hall, the Posidonio aquatic complex and to many restored mansions of past affluent residents of the city, which today serve as museums or cultural centers. The municipality of Kalamaria is also located in southeastern Thessaloniki and has become this part of the city’s most sought after areas, with many open spaces and home to high end bars, cafes and entertainment venues, most notably on Plastira street, along the coast.

Northwestern Thessaloniki

Northwestern Thessaloniki up until the 1980’s had always been associated with industry and the lower-middle class due to the fact that as the city grew during the 1920’s, many workers had moved there, due to its proximity near factories and industrial activities. Today many factories and industries have been moved further out northwest and the area is experiencing rapid growth as does the southeast. Many factories in this area have been converted to cultural centres, while past military grounds that are being surrounded by densely built neighborhoods are awaiting transformation into large parklands.

Northwestern Thessaloniki forms the main entry point into the city of Thessaloniki with the avenues of Monastiriou, Langada and Kontantinopoleos passing through it, as well as the Nea Ditiki Eisodos (extension of the A1 motorway). The area is also home to the Macedonia Central Bus Station (intercity buses terminal) and large entertainment venues such as Milos, Fix, Vilka (which are housed in converted old factories) and to Moni Lazariston in Stauroupoli, which forms today the cultural centre for this part of the city.

Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments

Due to Thessaloniki's importance during the early Christian and Byzantine periods, the city is host to several paleochristian monuments that have significantly contributed to the development of the arts in the Byzantine Empire as well as Serbia.[28] The evolution of Imperial Byzantine architecture and the prosperity of Thessaloniki go hand in hand, especially during the first years of the Empire,[28] when the city continued to flourish. It was at that time that the Complex of Roman emperor Galerius was built, as well as the first church of Hagios Demetrios.[28]

By the 8th century, the city had become an important administrative center of the Byzantine Empire, and handled much of the Empire's Balkan affairs.[29] During that time, the city saw the creation of more notable Christian churches that are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites, such as Hagia Sophia of Thessaloniki.[28] When the Ottoman Empire took control of Thessaloniki in 1430, most of the city's churches were converted into mosques,[28] but have survived to this day. Travelers such as Paul Lucas and Abdul Mecid[28] document the city's wealth in Christian monuments during the years of the Ottoman control of the city.

The church of Hagios Demetrios burned down during the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, as did many other of the city's monuments, but were rebuilt. During the Second World War, the city was extensively bombed and as such many of Thessaloniki's paleochristian and Byzantine monuments were heavily damaged.[29] Some of the sites were not restored until the 1980s. Thessaloniki has more listed UNESCO World Heritage Sites than any other city in Greece, a total of 9 buildings and structures.[28] They have been listed since 1988.[28]

Thessaloniki 2012 Program

In regards to the 100th anniversary of the incorporation of Thessaloniki into Greece, during 1912, the government announced a large-scale redevelopment program for the city of Thessaloniki, which aims in addressing the current environmental and spatial problems[30] that the city faces. More specifically, the program will drastically change the physiognomy of the city[30] by relocating the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Center and grounds of the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair outside the city centre and turning the current location into a large metropolitan park,[31] redeveloping the coastal front of the city,[31] relocating the city's numerous military camps and using the grounds and facilities to create large parklands and cultural centers,[31] and the complete redevelopment of the harbor and the Dendropotamos region of the city into a thriving business district.[31] The plan also envisions the creation of new wide avenues in the outskirts of the city[31] and the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre.[31] Furthermore, the program includes plans to expand the jurisdiction of Seich Sou Forest National Park,[30] and the improvement of accessibility to and from the Old Town.[30] The ministry has said that the project will take an estimated 15 years to be completed, in 2025.[31]

Part of the plan has been implemented with the revitalisation of half the eastern urban waterfront (nea paralia), with a modern and vibrant design. The municipality of Thessaloniki's budget for the reconstruction of important areas of the city and most notably the rest of the waterfront, is estimated to be around €28.2 million (US$39.9 million) for the year 2011 alone.[32]

Government

Local government

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2011) |

According to the Kallikratis reform, as of 1 January 2011 the Thessaloniki Urban Area (Template:Lang-el) is made up of six self-governing municipalities (Template:Lang-el) and one municipal unit (Template:Lang-el). The municipalities that are included in the Thessaloniki Urban Area are those of Pavlos Melas, Kordelio-Evosmos, Ampelokipoi-Menemeni, Neapoli-Sykies, Thessaloniki, Kalamaria and the municipal unit of Pylaia, part of the Municipality of Pylaia-Chortiatis. Prior to the Kallikratis reform, Thessaloniki was made up of twice that many municipalities, considerably smaller in size, which created bureaucratic problems.[33]

Other

Thessaloniki is the second largest city in Greece. It is an influential city for the northern parts of the country and the capital of the Central Macedonia Periphery, the Thessaloniki Prefecture and at the Municipality of Thessaloniki. The General Secretariat for Macedonia and Thrace is also based in the city. Thessaloniki is also the de facto capital of the Greek region of Macedonia.

It is customary every year for the Prime Minister of Greece to announce his administration's policies on a number of issues, such as the economy, at the opening night of the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair. In 2010, during the first months of the 2010 Greek debt crisis, the entire cabinet of Greece met in Thessaloniki to discuss the country's future.[34]

Economy

Thessaloniki is a major port city and an industrial and commercial centre. The city's industries centre around oil, steel, petrochemicals, textiles, machinery, flour, cement, pharmaceuticals, and liquor.

The city's port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest ports in the Aegean and as a free port, it functions as a major gateway to the Balkan hinterland.[35] In the first six months of 2010, more that 7.2 million tons of products went through the city's port,[36] making it one of the largest and most used ports in the Balkans. The city is also a major transportation hub for the whole of south-eastern Europe,[37] carrying among other things, trade to and from the neighbouring countries. Recently Thessaloniki is also slowly turning into a major port for cruising in the eastern Mediterranean.[35]

In recent years, the city has suffered industrial restructuring and lost many jobs; while it is moving toward a more service-based economy. A spate of factory shut downs has occurred as companies take advantage of cheaper labour markets and more lax regulations in other areas. Among the largest companies to shut down factories are Goodyear,[38] AVEZ (the first industrial factory in northern Greece, built in 1926),[39] and VIAMIL (ΒΙΑΜΥΛ). Nevertheless Thessaloniki still remains a major business hub in the Balkans.

A number of important Greek companies are headquartered in Thessaloniki, such as the Hellenic Vehicle Industry, the Macedonian Milk Industry and Philkeram-Johnson. A considerable percentage of the city's working force is employed in small and medium-sized businesses, as well as in the service and the public sectors.

The GDP of the prefecture of Thessaloniki was €18.4 billion (US$25.4 billion) in 2004,[40] and the GDP per capita of the prefecture was €17,394 (US$24,027),[40] which was above Greece's GDP per capita at the time (US$20,000).[41]

Demographics

Historical ethnic statistics

The tables below show the ethnic statistics of Thessaloniki during the end of 19th and the beginning of 20th century.

| Year | Total Population | Jewish Population | Turkish (Muslim) Population | Greek Population | Bulgarian Population | Roma Population | Other groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890[42] | 118,000 | 55,000 | 26,000 | 16,000 | 10,000 | 2,500 | 8,500 |

| around 1913[43] | 157,889 | 61,439 | 45,889 | 39,956 | 6,263 | 2,721 | 1,621 |

Population growth

Although the population of the Municipality of Thessaloniki has declined in the last two censuses, the metropolitan area's population is still growing. The city forms the base of the metropolitan area.

| Year | Urban area | |

|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 70,000[44] | – |

| 1870 | 90,000[44] | – |

| 1882 | 85,000[44] | – |

| 1890 | 118,000 | – |

| 1902 | 126,000[44] | – |

| 1913 | 157,000[27] | – |

| 1917 | 230,000[27] | – |

| 1981 | 406,413 | – |

| 1991 | 383,967[45] | – |

| 2001 | 363,987[45] | 773,180[45] |

| 2004 | 386,627[46] | - |

The Jews of Thessaloniki

The Jewish population in Greece was the oldest in mainland Europe, and was mostly Sephardic. Thessaloniki became the largest center of the Sephardic Jews, who nicknamed the city la madre de Israel (Israel's mother) because of this.[47] Some also claim that Thessaloniki is part of Great Israel, including names such as "City of Israel" and "Jerusalem of the Balkans". [48] It also included the historically significant and ancient Greek-speaking Romaniote community. During the Ottoman era, Thessaloniki's Sephardic community comprised more than half the city's population; the Jews were dominant in commerce until the ethnic Greek population increased after independence in 1912. By the 1680s, about 300 families of Sephardic Jews, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, had converted to Islam, becoming a sect known as the Dönmeh (convert), and migrated to Salonika, whose population was majority Jewish. They established an active community that thrived for about 250 years. Many of their descendants later became prominent in trade.[49] Many Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki spoke Ladino, the Romance language of the Sephardic Jews.[50]

The great fire of 1917 burned much of the center of the city and left 50,000 Jews homeless of the total of 72,000 residents who were burned out.[21] Having lost homes and their businesses, many Jews emigrated: to the United States, Palestine, and Paris. They could not wait for the government to create a new urban plan for rebuilding, which was eventually done.[51]

After the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the expulsion of Greeks from Turkey, many refugees came to Greece. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in Thessaloniki, reducing the proportion of Jews in the total community. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city's population. During the interwar period, Greece granted the Jews the same civil rights as other Greek citizens.[21] In March 1926, Greece re-emphasized that all citizens of Greece enjoyed equal rights, and a considerable proportion of the city's Jews decided to stay.

World War II brought a disaster for the Jewish Greeks, since in 1941 the Germans occupied Greece and began actions against the Jewish population. Greeks of the Resistance and Italian forces (before 1943) tried to protect the Jews and managed to save some.[47] By the 1940s, the great majority of the Jewish Greek community firmly identified as both Greek and Jewish. According to Misha Glenny, such Greek Jews had largely not encountered "anti-Semitism as in its North European form."[52]

In 1943 the Nazis began actions against the Jews in Thessaloniki, forcing them into a ghetto near the railroad lines and beginning deportation to concentration and labor camps. They deported and exterminated approximately 96% of Thessaloniki's Jews of all ages during the Holocaust.[47] Today, a community of around 1200 remains in the city.[47] Communities of descendants of Thessaloniki Jews – both Sephardic and Romaniote – live in other areas, mainly the United States and Israel.[47]

Israeli singer Yehuda Poliker recorded a song about the Jews of Thessaloniki, called "Wait for me, Thessaloniki".

| Year | Total population |

Jewish population |

Jewish percentage |

Source[21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 70,000 | 36,000 | 51% | Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer |

| 1870 | 90,000 | 50,000 | 56% | Greek schoolbook (G.K. Moraitopoulos, 1882) |

| 1882/84 | 85,000 | 48,000 | 56% | Ottoman government census |

| 1902 | 126,000 | 62,000 | 49% | Ottoman government census |

| 1913 | 157,889 | 61,439 | 39% | Greek government census |

| 1917 | 271,157 | 52,000 | 19% | [53] |

| 1943 | 50,000 | |||

| 2000 | 363,987[45] | 1,000 | 0.27% |

Culture

Leisure and entertainment

Thessaloniki is regarded as the cultural and entertainment capital of northern Greece.[29] The city's main theaters, run by the National Theater which was established in 1961,[54] include the Theater of the Society of Macedonian Studies, where the National Theater is based, the Royal Theater, the first base of the National Theater, Moni Lazariston, and the Earth Theater and Forest Theater, both amphitheatrical open-air theatres overlooking the city.[54]

The award of the European Capital of Culture in 1997 saw the birth of the city's first opera[55] and today forms an independent section of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[56] The opera is based at the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, one of the largest concert halls in Greece. Recently a second building was also constructed and designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki.

Olympion Theater, the site of the Thessaloniki International Film Festival and the Plateia Assos Odeon multiplex are the two major cinemas in downtown Thessaloniki. The city also has a number of multiplex cinemas in major shopping centres in the suburbs, most notably in Mediterranean Cosmos, the largest retail and entertainment development in the Balkans.

Thessaloniki is renowned for its major shopping streets and lively laneways. Tsimiski Street and Proxenou Koromila avenue are the city's most famous shopping streets and are among Greece's most expensive and exclusive high streets. The city is also home to one of Greece's most famous and prestigious hotels, Makedonia Palace hotel, the Hyatt Regency Casino and hotel (the biggest casino in Greece and one of the biggest in Europe) and Waterland, the largest water park in southeastern Europe.

The city has always been known between Greeks for its vibrant city culture, including having the most cafe's and bars per-capita than any other city in Europe; and as having some of the best nightlife and entertainment in the country, thanks to its large young population and multicultural feel. Only recently has the city been exposing itself to the world and becoming more known for what it is, with Lonely Planet listing Thessaloniki as the world's fifth-best ultimate party city.[57]

Museums and galleries

Due to the city's rich and diverse history, Thessaloniki houses many museums dealing with many different eras in history. The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki was established in 1962 and houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts,[58] including an extensive collection of golden artwork from the royal palaces of Aigai and Pella.[59] It also houses exhibits from Macedon's prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze age.[60] The Prehistoric Antiquities Museum of Thessaloniki has exhibits from those periods as well.

One of the most modern museums in the city is the Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum and is one of the most high-tech museums in Greece and southeastern Europe.[61] It features the largest planetarium in Greece, a cosmotheater with the largest flat screen in Greece, an amphitheater, a motion simulator with 3D projection and 6-axis movement and exhibition spaces.[61] Other industrial and technological museums in the city include the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, which houses an original Orient Express train, the War Museum of Thessaloniki and others. The city also has a number of educational and sports museums, including the Thessaloniki Olympic Museum and the Sports Museum of Thessaloniki.

The Atatürk Museum in Thessaloniki is the historic house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern-day Turkey, was born. The house is now part of the Turkish consulate complex, but admission to the museum is free.[62] The museum contains historic information about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his life, especially while he was in Thessaloniki.[62] Other ethnological museums of the sort include the Historical Museum of the Balkan Wars, the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, containing information about the freedom fighters in Macedonia and their struggle to liberate the region from the Ottoman yoke.[63]

The city also has a number of important art galleries. Such include the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, housing exhibitions from a number of well-known Greek and foreign artists.[64] The Teloglion Foundation of Art is part of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and includes an extensive collection of works by important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, including works by prominent Greeks and native Thessalonians.[65] The Thessaloniki Museum of Photography also houses a number of important exhibitions, and is located within the old port of Thessaloniki.[66]

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is one of the city's most famous museums, showcasing the city's glorious Byzantine past.[67] The museum was also awarded Council of Europe's museum prize in 2005.[68] The museum of the White Tower of Thessaloniki houses a series of galleries relating to the city's past, from the creation of the White Tower until recent years.[69]

Festivals

Thessaloniki is home of a number of festivals and events. The Thessaloniki International Trade Fair is the most important event to be hosted in the city annually, by means of economic development. It was first established in 1926[70] and takes place every year at the 180,000m² Thessaloniki International Exhibition Center. The event attracts major political attention and it is customary for the Prime Minister of Greece to outline his administration's policies for the next year, during event. Over 300,000 visitors attended the exposition in 2007[citation needed].

The Thessaloniki International Film Festival is established as one of the most important film festivals in Southern Europe,[71] with a number of notable film makers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas and Fatih Akın taking part, and was established in 1960.[72] The Documentary Festival, founded in 1999, has focused on documentaries that explore global social and cultural developments, with many of the films presented being candidates for FIPRESCI and Audience Awards.[73]

The Dimitria festival, founded in 1966 and named after the city's patron saint of St. Demetrius, has focused on a wide range of events including music, theatre, dance, local happenings, and exhibitions.[74] The "DMC DJ Championship" has been hosted at the International Trade Fair of Thessaloniki and has become a worldwide event for aspiring DJs and turntablists. The "International Festival of Photography" has taken place every February to mid-April.[75] Exhibitions for the event are sited in museums, heritage landmarks, galleries, bookshops and cafés. Thessaloniki also holds an annual International Book Fair.[76]

Sports

The main stadium of the city is the Kaftanzoglio Stadium (also home ground of Iraklis FC) , while other main stadiums of the city include the football Toumba Stadium and Kleanthis Vikelidis Stadium, home grounds of PAOK FC and Aris FC respectively, all of whom are founding members of the Greek league.

Being the largest "multi-sport" stadium in the city, Kaftanzoglio Stadium regularly plays host to athletics events; such as the European Athletics Association event "Olympic Meeting Thessaloniki" every year; it has hosted the Greek national championships in 2009 and has been used for athletics at the Mediterranean Games and for the European Cup in athletics. In 2004 the stadium served as an official Athens 2004 venue,[77] while in 2009 the city and the stadium hosted the 2009 IAAF World Athletics Final.

Thessaloniki's major indoor arenas include the state-owned Alexandreio Melathron, PAOK Sports Arena and the YMCA indoor hall. Other sporting clubs in the city include Apollon FC based in Kalamaria, Agrotikos Asteras FC based in Evosmos and YMCA. Thessaloniki has a rich sporting history with its teams winning the first ever panhellenic football,[78] basketball,[79] and water polo[80] tournaments.

The city played a major role in the development of basketball in Greece. The local YMCA was the first to introduce the sport to the country, while Iraklis BC won the first ever Greek championship.[79] From 1982 to 1993 Aris BC dominated the league, regularly finishing in first place. In that period Aris won a total of 9 championships, 7 cups and one European Cup Winners' Cup. In volleyball, Iraklis has emerged since 2000 as one of the most successful teams in Greece[81] and Europe.[82][83] In October 2007, Thessaloniki also played host to the first Southeastern European Games.[84]

The city is also the finish point of the annual Alexander The Great Marathon, which starts at Pella, in recognition of its Ancient Macedonian heritage.[85]

|

|

Media

Thessaloniki is home to the ERT3 TV-channel and Radio Macedonia, both services of Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ERT) operating in the city and are broadcast all over Greece.[86] The municipality of Thessaloniki also operates three radio stations, namely FM100, FM101 and FM100.6;[87] and TV100, a television network which was also the first non-state-owned TV station in Greece and opened in 1988.[87]

The city's main newspapers and some of the most circulated in Greece, include Makedonia, which was also the first newspaper published in Thessaloniki in 1911 and Aggelioforos. A large number of radio stations also broadcast from Thessaloniki as the city is known for its music contributions.

Notable Thessalonians

Throughout its history, Thessaloniki has been home to a number of well-known figures. It is also the birthplace of various Saints, such as Cyril and Methodius, creators of the Cyrillic alphabet. Many of Greece's most celebrated musicians and movie stars were born in Thessaloniki, such as Zoe Laskari and Marinella. Additionally, there have been a number of political leaders born in the city, such as the founder of modern-day Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, and the current Minister of Defence of Greece, Evangelos Venizelos.

Thessaloniki in popular culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2011) |

The city is viewed as a romantic one in Greece, and as such Thessaloniki is commonly featured in Greek songs.[88] There are a number of famous songs that go by the name 'Thessaloniki' or include the name in their title.[89]

Education

Thessaloniki is a major center of education for Greece. Two of the country's largest universities are located in central Thessaloniki: Aristotle University and the University of Macedonia. Aristotle University was founded in 1926 and is currently the largest university in Greece[29] by number of students, which number at more than 80,000 in 2010,[29] and is a member of the Utrecht Network. For the academic year 2009-2010, Aristotle University was ranked as one of the 150 best universities in the world for arts and humanities and among the 250 best universities in the world overall by the Times QS World University Rankings,[3] making it one of the top 2% of best universities worldwide.[90] Leiden ranks Aristotle University as one of the top 100 European universities and the best university in Greece, at number 97.[91] Since 2010, Thessaloniki is also home to the Open University of Thessaloniki,[92] which is funded by Aristotle University, the University of Macedonia and the municipality of Thessaloniki.

Additionally, a TEI (Technological Educational Institute) is located in the western suburb of Sindos, home also to the industrial zone of the city. Numerous public and private vocational institutes (Template:Lang-el) provide professional training to young students, while a large number of private colleges offer American and UK academic curriculum, via cooperation with foreign universities. In addition to Greek students, the city hence attracts many foreign students either via the Erasmus programme for public universities, or for a complete degree in public universities or in the city's private colleges. As of 2006[update] the city's total student population was estimated around 200,000.[93]

Transportation

Bus transport

Public transport in Thessaloniki is by buses. The bus company operating in the city is the Thessaloniki Urban Transport Organization (OASTH), and is the only public means of transportation in Thessaloniki at the moment. It operates a fleet of 604 vehicles on 75 routes throughout the Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area. International and regional bus links are provided at the Macedonia Central Bus Station (intercity buses terminal), located west of the city centre.

Railways

The city is a major railway hub for the Balkans, with direct connections to Sofia, Skopje, Belgrade, Moscow, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest and Istanbul, alongside Athens and other destinations in Greece. It is the most important railway hub of Greece and has the biggest marshalling yard in the country.

Thessaloniki's railway passenger station, is called the "New Railway Station" and was completed in 1961,[94] remaining largely unchanged ever since. Currently it features large waiting areas, a central hall, cafes, restaurants and a shopping center. Discussions are underway for the expansion of the station and a general modernisation overhaul, which will also include a hotel and a revamp of the central offices of the Hellenic Railways Organization for northern Greece.[95] A metro station is currently also under construction at the station.

Commuter rail services have recently been established between Thessaloniki and the city of Larissa (the service is known in Greek as the "Proastiakos", meaning "Suburban Railway"). The service operates on a modernised electrified double track and stops at 11 refurbished stations, covering the journey in an 1 hour and 33 minutes. The train service within Greece, including the Proastiakos, is operated by TrainOSE, the Hellenic Railways Organization's train operating company. As of 2011, due to the financial crisis international services have been suspended.

Thessaloniki Metro

The construction of the Thessaloniki Metropolitan Railway began in 2006 and is scheduled for completion in late 2014.[96] The line of Phase 1 is set to extend over 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi), include 13 stations[97] and it is expected to eventually serve 250,000 passengers daily.[98] Some stations of the Thessaloniki Metro will house a number of archaeological finds.[99]

Discussions are already underway for future expansions, in order for the metro network to also serve major transport hubs of the city, notably the Macedonia Central Bus Station (intercity buses terminal) and Macedonia International Airport. For the expansion towards the airport, the Attiko Metro company is considering the construction of an overground network or a monorail. The expansion to Kalamaria, a southeast borough of Thessaloniki, has already become part of the initial construction phase, while future expansions are considered and planned for Efkarpia to the north and Evosmos to the west. The strategic plan for the construction of the Thessaloniki Metro envisions that the city will have a system of 3 lines by 2018 or 2020 at the latest.[100]

Macedonia International Airport

Air traffic to and from the city is served by Macedonia International Airport for international and domestic flights. The short length of the airport's two runways means that it does not currently support intercontinental flights, although a major extension, lengthening one of its runways into the Thermaic Gulf is under construction, despite considerable opposition from local environmentalist groups. Following the completion of the runway works, the airport will be able to serve intercontinental flights and cater for larger aircraft in the future. A master-plan, with designs for a new terminal building and apron have also been released; and is seeking for either public and private funding.

Motorways

The city is bypassed by a C-shaped ring road. The western end of the route begins at the junction with the A1/A2 motorways in Lachanagora District. Clockwise it heads northeast around the city, passing through the north-western suburbs, the forest of Seich Sou and through to the southeast borough of Kalamaria. The ring road ends at a large junction with the ΕΟ67 (in the near future to be expanded as A25) motorway, which then continues down to Chalkidiki. This route is labeled as the Esoteriki Peripheriaki Odos (Template:Lang-el, inner ring road) of Thessaloniki and is generally accepted as the boundary between the city proper and its suburbs.

The speed limit on this motorway is 90 kilometres per hour (56 mph) and provides three traffic lanes for each direction. Although the large efford that was made in 2004 to improve the motorway features, it still does not feature an emergency lane. New plans have surfaced to upgrade the motorway to address the current issues, while also adding one more lane in each direction.

An outer ring known as Eksoteriki Peripheriaki Odos (Template:Lang-el, outer ring road) is planned, with its west part already built and running as part of the A1/A2 motorways.

- Motorways:

- A1/E75 W (Republic of Macedonia, Athens, Larissa)

- A2/E90 N' (Turkey, Alexandroupolis, Kavala, Xanthi, Igoumenitsa, Ioannina, Kozani)

- National Roads (part motorways):

Twin towns — sister cities

Thessaloniki is twinned with:[101]

Towns

|

Collaborations

|

Gallery

-

Detail from the Arch of Galerius.

-

View of Yeni Mosque, built during the ottoman period.

-

Aerial view of the City Centre.

-

The Metropolitan Church of Saint Gregory Palamas.

-

The White Tower of Thessaloniki is the most famous landmark of the city.

-

Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum (also known as NOESIS).

-

Art Nouveau building at the center of the city.

-

View of the seafront.

See also

References

Bibliography

- Apostolos Papagiannopoulos,Monuments of Thessaloniki, Rekos Ltd, date unknown.

- Apostolos P. Vacalopoulos, A History of Thessaloniki, Institute for Balkan Studies,1972.

- John R. Melville-Jones, 'Venice and Thessalonica 1423–1430 Vol I, The Venetian Accounts, Vol. II, the Greek Accounts, Unipress, Padova, 2002 and 2006 (the latter work contains English translations of accounts of the events of this period by St Symeon of Thessaloniki and John Anagnostes).

- Thessaloniki: Tourist guide and street map, A. Kessopoulos, Malliarēs-Paideia, 1988.

- Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430–1950, 2004, ISBN 0-375-41298-0.

- Thessaloniki City Guide, Axon Publications, 2002.

- Eugenia Russell, St Demetrius of Thessalonica; Cult and Devotion in the Middle Ages, Peter Lang, Oxford, 2010. ISBN 978 3 0343 0181 7

- James C. Skedros, Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki: Civic Patron and Divine Protector, 4th-7Th Centuries (Harvard Theological Studies), Trinity Press International (1999).

- Vilma Hastaoglou-Martinidis (ed.), Restructuring the City: International Urban Design Competitions for Thessaloniki, Andreas Papadakis, 1999.

- Matthieu Ghilardi, Dynamiques spatiales et reconstitutions paléogéographiques de la plaine de Thessalonique (Grèce) à l'Holocène récent, 2007. Thèse de Doctorat de l'Université de Paris 12 Val-de-Marne, 475 p.

Notes

- ^ "Urban Audit – Data that can be accessed". Urbanaudit.org. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ AIGES oHG, www.aiges.net. "SAE – Conventions". En.sae.gr. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ a b Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings

- ^ "Definition of Thessaloniki". Allwords.com. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ Ανδριώτης (Andriotis), Νικόλαος Π. (Nikolaos P.) (1995). Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας: (τέσσερις μελέτες) (History of the Greek language: four studies) (in Greek). Θεσσαλονίκη (Thessaloniki): Ίδρυμα Τριανταφυλλίδη. ISBN 960-231-058-8.

- ^ Vitti, Mario (2001). Storia della letteratura neogreca (in Italian). Roma: Carocci. ISBN 88-430-1680-6.

- ^ Strabo VIII Fr. 21,24 – Paul's early period By Rainer Riesner, Doug Scott, p. 338, ISBN 0-8028-4166-X

- ^ Peter E. Lewis, Ron Bolden, The pocket guide to Saint Paul, p. 118, ISBN 1862545626

- ^ a b c White Tower Museum - A Timeline of Thessaloniki

- ^ Coates, Alan ; Bodleian Library (2005). A Catalogue of Books Printed in the Fifteenth Century Now in the Bodleian Library. Oxford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 0199519056.

Theodorus Graecus Thessalonicensis

{{cite book}}: Text "ie Theodorus Gaza" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cuvier, Georges (baron) ; Cuvier, Georges; Pietsch, Theodore W. (1995). Historical portrait of the progress of ichthyology: from its origins to our own time. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0801849144.

Theodorus of Gaza — [b. ca. 1400] a Greek from Thessalonica.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ cf. the account of John Anagnostes.

- ^ a b "Thessaloniki". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

At the end of that century the severely reduced population was augmented by an influx of 20,000 Jews driven from Spain.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 371. ISBN 0521428947.

The capture and sack of Thessalonica is vividly described by an eye-witness, John Anagnostes. He reckoned that 7000 citizens, perhaps one-fifth of the population, were carried off to slavery.

- ^ Harris, Jonathan (1995). Greek emigres in the West 1400–1520. Porphyrogenitus. p. 12. ISBN 187132811X.

Many of the inhabitants of Thessalonica fled to the Venetian colonies in the early fifteenth century, in the face of sporadic attacks which culminated in the city's capture by Murad II in the 1430's.

- ^ Milner, Henry (2009). The Turkish Empire: The Sultans, the Territory, and the People. BiblioBazaar. p. 87. ISBN 1113223995.

Theodore Gaza, one of these exiles, escaped from Saloniki, his native city, upon its capture by Amurath.

- ^ Rosamond McKitterick, Christopher Allmand, The New Cambridge Medieval History, p. 779

- ^ 100+1 Years of Greece, Volume I, Maniateas Publishings, Athens, 1995. pp. 148-149

- ^ Mavrogordatos, George Themistocles (1983), Stillborn republic: social coalitions and party strategies in Greece, 1922-1936, Univ. of California, p. 284, ISBN 0520043588

- ^ Gerolympos, Alexandra Karadimou. The Redesign of Thessaloniki after the Fire of 1917. University Studio Press, Thessaloniki, 1995

- ^ a b c d Yakov Benmayor. "History of Jews in Thessaloniki". Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ a b "Salamo Arouch, 86, survived Auschwitz by boxing", Haaretz

- ^ PDF file

- ^ a b c 100+1 Years of Greece, Volume II, Maniateas Publishings, Athens, 1999. pp 210-211.

- ^ "Weather Information for Thessaloniki".

- ^ Average conditions for Thessaloniki, Greece - BBC Weather

- ^ a b c d Gerolympos, Alexandra Karadimou. The Redesign of Thessaloniki after the Fire of 1917. University Studio Press, Thessaloniki, 1995

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paleochristian and Byzantine Monuments of Thessalonika

- ^ a b c d e Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, "The City of Thessaloniki" (in Greek) Cite error: The named reference "AUTH" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Hellenic Government - Thessaloniki 2012 Program (in Greek)

- ^ a b c d e f g Ministry of the Environment, of Energy and of Climate Change - Complete presentation (in Greek)

- ^ "Στα 28 εκατ. ευρώ το τεχνικό πρόγραμμα του δήμου". Makedonia (in Greek). Thessaloniki. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ The Metropolitan Governance of Thessaloniki! (in Greek)

- ^ ΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ. "Πρεμιέρα Υπουργικού με τρία νομοσχέδια". Δημοσιογραφικός Οργανισμός Λαμπράκη Α.Ε. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b "The Port City", Thessaloniki Port Authority.

- ^ Half-yearly financial Report 2010 (in Greek)

- ^ Shipping Agents Association of Thessaloniki

- ^ PFI (ΒΦΛ)

- ^ "Information is in Greek from one of the city's largest dailies". Makthes.gr. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ a b Official statistics of the Periphery of Central Macedonia

- ^ IndexMundi data

- ^ Васил Кънчов (1970). "Избрани произведения", Том II, "Македония. Етнография и статистика" (in Bulgarian). София: Издателство "Наука и изкуство". p. g. 440. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Συλλογικο εργο (1973). "Ιστορια του Ελληνικου Εθνους",History of Greek Nation Том ΙΔ, (in Greek and English). ATHENS: "ΕΚΔΟΤΙΚΗ ΑΘΗΝΩΝ". p. g. 340.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d Molho, Rena.The Jerusalem of the Balkans: Salonica 1856-1919 The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki. URL accessed July 10, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Population of Greece". General Secretariat Of National Statistical Service Of Greece. www.statistics.gr. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Eurostat regional yearbook 2010". Eurostat. www.eurostat.eu. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ a b c d e www.ushmm.org "Jewish Community in Greece", Online Exhibit, US Holocaust Museum, accessed 29 December 2010

- ^ Abrams, Dennis (2009); Nicolas Sarkozy (Modern World Leaders), Chelsea House Publishers, p. 26, Library Binding edition, ISBN 1604130814

- ^ Kirsch, Adam The Other Secret Jews - Review of Marc David Baer's The Dönme: Jewish Converts, Muslim Revolutionaries, and Secular Turks, The New Republic, 15 Feb 2010, accessed 21 Feb 2010

- ^ Kushner, Aviya. "Is the language of Sephardic Jews, undergoing a revival?". My Jewish Learning. Ladino Today. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ "The Great Fire in Salonica". Greece History. Hellenica Website. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Misha Glenny, The Balkans, p. 512.

- ^ J. Nehama, Histoire des Israélites de Salonique, t. VI-VII, Thessalonique 1978, p. 765 (via Greek Wikipedia): the population was inflated because of refugees from the First World War

- ^ a b 'History', National Theater of Northern Greece website (in Greek)

- ^ "Cultural Capital". Music.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ "Όπερα Θεσσαλονίκης". Ntng.gr. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Ultimate Party Cities - Lonely Planet

- ^ In Macedonia from the 7th c. BC until late antiquity

- ^ The Gold of Macedon

- ^ 5,000, 15,000, 200,000 years ago... An exhibition about prehistoric life in Macedonia

- ^ a b NOESIS - About the Museum (in Greek)

- ^ a b About Ataturk Museum

- ^ The Museum of the Macedonian Struggle - Introduction (in Greek)

- ^ The Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art - List of artists

- ^ The Teloglion Foundation of Art - The Collection

- ^ Photography Museum of Thessaloniki - Exhibitions

- ^ About the Museum (in Greek)

- ^ Award of the Council of Europe to the Museum of Byzantine Culture (in Greek)

- ^ Introduction video of the White Tower Museum

- ^ Thessaloniki International Trade Fair - History and actions (in Greek)

- ^ Thessaloniki International Film Festival - Profile (in Greek)

- ^ List of posters

- ^ Thessaloniki Documentary Festival - Awards Template:Gr icon

- ^ Dimitria Festival official website (in Greek)

- ^ Article on Culturenow (in Greek)

- ^ "The Exhibition". The Thessaloniki Book Fair. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ List of Athens 2004 venues (in Greek)

- ^ "Galanis Sports Data". Galanissportsdata.com. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ a b "Galanis Sports Data". Galanissportsdata.com. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ "Κόκκινος Ποσειδώνας: Πρωταθλητής Ελλάδας στο πόλο ο Ολυμπιακός για 21η φορά στην ιστορία του! – Pathfinder Sports". Sports.pathfinder.gr. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ "Άξιος πρωταθλητής ο Ηρακλής – Παναθηναϊκός, Ηρακλής – Contra.gr". Contra.gr. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ magic moving pixel s.a. (2005-03-27). "F-004 – TOURS VB vs Iraklis THESSALONIKI". Cev.lu. Retrieved 2009-01-05. [dead link]

- ^ "Men's CEV Champions League 2005–06 – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia". En.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ 1οι Αγώνες των χωρών της Νοτιανατολικής Ευρώπης – SEE games – Thessaloniki 2007

- ^ Presentation. Alexander the Great Marathon. Retrieved on 2010-04-28.

- ^ "PROFILE". EPT TV-Radio. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b History of the Comapny (in Greek)

- ^ date=2007-06-04 "Τραγούδια για τη Θεσσαλονίκη 2". homelessmontresor. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - ^ "Τραγούδια για την Θεσσαλονίκη". Musicheaven.gr. 2010-02-13. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ The International Journal of Scientometrics, Infometrics and Bibliometrics estimates that there are 17036 universities in the world.

- ^ official list

- ^ Open University (in Greek).

- ^ "Thessaloniki has no Apple's real representation". Karakatsanis, Dimitris. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ "Αναμόρφωσις Σιδηροδρομικού Σταθμού Θεσσαλονίκης" (PDF). 1961. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ "Αλλάζει ο Σιδηροδρομικός Σταθμός της Θεσσαλονίκης". Newsfilter. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Attiko Metro A.E. (10 March 2011). "Δηλώσεις του Υφυπουργού κ. Γιάννη Μαγκριώτη στο Σταθμό ΕΥΚΛΕΙΔΗΣ του ΜΕΤΡΟ". Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ "Thessaloniki metro "top priority", Public Works minister says". Athens News Agency. www.ana.gr. 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ "CONCLUSION OF CONTRACT FOR THE THESSALONIKI METRO". Attiko Metro S.A. www.ametro.gr. 2006-04-07. Archived from the original on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ "CONCLUSION THESSALONIKI METRO & ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION". Attiko Metro S.A. www.ametro.gr. 2007-04-12. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ Attiko Metro A.E. (3 February 2011). "Το 2018 η Θεσσαλονίκη θα έχει Δίκτυο Γραμμών Μετρό". Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Αδελφοποιημένες Πόλεις". City of Thessaloniki. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ "Bratislava City – Twin Towns". © 2003–2008 Bratislava-City.sk. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "Hartford Sister Cities International". Harford Public Library. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ^ "International relations: Thessaloniki". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Fun Facts and Statistics". City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ^ . /subject/2008/DgThessaloniki/ "Dongguan and Salonica Formed Sisterhood". Retrieved 2008-10-27.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

External links

Government

- Municipality of Thessaloniki

- Thessaloniki Port Authority

- ΟΑΣΘ – Organisation of Urban Transport of Thessaloniki (Greek & English)

- Thessaloniki – Photo Archive Documents 1900–1980

Cultural

- Thessaloniki

- Populated coastal places in Greece

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Greece

- Greek prefectural capitals

- Greek regional capitals

- Prefecture of Thessaloniki

- Populated places in the Thessaloniki Prefecture

- Tourism in Greece

- Pauline churches

- World Heritage Sites in Greece

- 310s BC establishments

- Populated places established in the 4th century BC

- Historic Jewish communities

- Geography of ancient Mygdonia

- European Capitals of Culture