Kharkiv

Kharkiv (Харків) | |

|---|---|

Freedom Square, Kharkiv | |

|

| |

Map of Ukraine with Kharkiv highlighted. | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Kharkiv Oblast |

| Municipality | Kharkiv City Municipality |

| Founded | 1654 |

| City rights | 1552–1654 |

| Districts | List of 9

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gennady Kernes |

| Area | |

• City | 310 km2 (120 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 152 m (499 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

• City | 1,449,000 |

| • Density | 4,500/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,732,400 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 61001—61499 |

| Licence plate | ХА, 21 (old) |

| Sister cities | Belgorod, Bologna, Cincinnati, Kaunas, Lille, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Nuremberg, Poznań, St. Petersburg, Tianjin, Jinan, Kutaisi, Varna, Rishon LeZion, Brno, Daugavpils |

| Website | http://www.city.kharkov.ua |

Kharkiv (Template:Lang-uk, pronounced [ˈxɑrkiw];[1]) or Kharkov (Template:Lang-ru) is the second-largest city in Ukraine.

Founded in 1654, Kharkiv became the first city in Ukraine where the Soviet power was proclaimed and Soviet government was formed. Now it is the administrative centre of the Kharkiv oblast (province), as well as the administrative centre of the surrounding Kharkivskyi Raion (district) within the oblast. The city is located in the northeast of the country. As of 2006, its population was 1,461,300.[2]

Kharkiv is a major cultural, scientific, educational, transport and industrial centre of Ukraine, with 60 scientific Institutes, 30 establishments of higher education, 6 museums, 7 theatres and 80 libraries. Its industry specializes mostly in machinery. There are hundreds of industrial companies in the city. Among them are world famous giants like the Morozov Design Bureau and the Malyshev Tank Factory, leaders in tank production since the 1930s; Khartron (aerospace and nuclear electronics); and the Turboatom turbines producer.

There is an underground rapid-transit system (metro) with about 38.1 km (24 mi) of track and 29 stations. A well-known landmark of Kharkiv is the Freedom Square (Maidan Svobody formerly known as Dzerzhinsky Square), which is currently the sixth largest city square in Europe, and the 12th largest square in the world.

Geography

Kharkiv is located in the northeastern region of Ukraine at around 49°55′0″N 36°19′0″E / 49.91667°N 36.31667°E. Historically, Kharkiv lies in the Sloboda Ukraine region (Slobozhanshchyna also known as Slobidshchyna), in which it is considered the main city. The city rests at the confluence of the Kharkiv, Lopan, and Udy rivers, where they flow into the Seversky Donets watershed.

Climate

Kharkiv's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb), with cold and snowy winters, and hot summers. The seasonal average temperatures are not too cold in winter, not too hot in summer: −6.9 °C (19.6 °F) in January, and 20.3 °C (68.5 °F) in July. The average rainfall totals 513 mm (20 in) per year, with the most in June and July.

| Climate data for Kharkiv, Ukraine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −8.5 (16.7) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.7) |

32 (1.3) |

27 (1.1) |

36 (1.4) |

47 (1.9) |

58 (2.3) |

60 (2.4) |

50 (2.0) |

41 (1.6) |

35 (1.4) |

44 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

549 (21.6) |

| Source: Weather and climate – Kharkiv's climate [3][4] | |||||||||||||

History

Archeological evidence discovered in the area of present-day Kharkiv indicates that a local population has existed in that area since the 2nd millennium BC. Cultural artifacts date back to the Bronze Age, as well as those of later Scythian and Sarmatian settlers. There is also evidence that the Chernyakhov culture flourished in the area from the 2nd to the 6th century.

Founded in the middle of 17th century by the eponymous, near-legendary character called Kharko (a diminutive form of the name Chariton, Template:Lang-uk), the settlement became a city in 1654. Kharkiv became the centre of the Sloboda cossack legion. The city had a fortress with underground passageways.

Within the Russian Empire

Kharkiv university was established in 1805. The streets were first cobbled in the city centre in 1830. RA system of running water was established in 1870. In 1912 the first sewerage system was built. Gas lighting was installed in 1890 and electric lighting in 1898. In 1869 the first railway station was constructed. In 1906 the first tram lines.

From 1800–1917 the population grew 30 times.

Kharkiv became a major industrial centre and with it a centre of Ukrainian culture. In 1812 the first Ukrainian newspaper was published there. One of the first Prosvitas in Eastern Ukraine was established in Kharkiv. A strong political movement was also established there and the concept of an Independent Ukraine was first declared there by the lawyer M. Mykhnovsky in 1900.

Soviet period

Prior to the formation of the Soviet Union, Bolsheviks established Kharkiv as the capital of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (from 1919–1934) in opposition to the Ukrainian People's Republic with its capital of Kiev.

As the country's capital, it underwent intense expansion with the construction of buildings to house the newly established Ukrainian Soviet government and administration. Derzhprom was the second tallest building in Europe and the tallest in the Soviet Union at the time with a height of 63 m.[5] In the 1920s, a 150 m wooden radio tower was built on top of the building. The radio tower was destroyed in World War II.

In 1928, the SVU (Union for the Freedom of Ukraine) process was initiated and court sessions were staged in the Kharkiv Opera (now the Philharmonia) building. Hundreds of Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested and deported.

In the early 1930s, the Holodomor famine drove many people off the land into the cities, and to Kharkiv in particular, in search of food. Many people died and were secretly buried in mass graves in the cemeteries surrounding the city.

In 1934 hundreds of Ukrainian writers, intellectuals and cultural workers were arrested and executed in the attempt to eradicate all vestiges of Ukrainian nationalism in Art. The purges continued into 1938. Blind Ukrainian street musicians were also gathered in Kharkiv and murdered by the NKVD.[6] In January 1935 the capital of the Ukrainian SSR was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev.

During April and May 1940 about 3,800 Polish prisoners of Starobelsk camp were executed in the Kharkiv NKVD building, later secretly buried on the grounds of an NKVD pansionat in Pyatykhatky forest (part of the Katyn massacre) on the outskirts of Kharkiv.[7] The site also contains the numerous bodies of Ukrainian cultural workers who were arrested and shot in the 1937–38 Stalinist purges.

Nazi occupation

During World War II, Kharkiv was the site of several military engagements. The city was captured and recaptured by Nazi Germany on 24 October 1941; there was a disastrous Red Army offensive that failed to capture the city in May 1942;[8][9] the city was successfully retaken by the Soviets on 16 February 1943, captured for a second time by the Germans on 16 March 1943 and then finally liberated on 23 August 1943. Seventy percent of the city was destroyed and tens of thousands of the inhabitants were killed. Kharkiv, the third largest city in the Soviet Union, was the most populous city in the Soviet Union captured by Nazis, since in the years preceding World War II, Kiev was by population the smaller of the two.

The significant Jewish population of Kharkiv (Kharkiv's Jewish community prided itself with the 2nd largest synagogue in Europe) suffered greatly during the war. Between December 1941 and January 1942, an estimated 30,000 people (slightly more than half Jewish) were killed and buried in a mass grave by the Germans in a ravine outside of town named Drobitsky Yar.

During World War II, four battles took place for control of the city:

- First Battle of Kharkov

- Second Battle of Kharkov

- Third Battle of Kharkov

- Fourth Battle of Kharkov (See also Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev)

Before the occupation, Kharkiv's tank industries were evacuated to the Urals with all their equipment, and became the heart of Red Army's tank programs (particularly, producing the legendary T-34 tank earlier designed in Kharkiv). These enterprises returned to Kharkiv after the war, and continue to produce some of the world's best tanks.

Post War

In the post-war period many of the destroyed homes and factories were rebuilt. Gas lines were installed for heating in government and later private homes. An airport was built in 1954.Following the war Kharkiv was the third largest scientific-industrial centre in the former USSR (after Moscow and Leningrad).

In independent Ukraine

In 2007, the Vietnamese minority in Kharkiv built the largest Buddhist temple in Europe on a 1 hectare plot with a monument to Ho Chi Minh.[10]

Government and administrative divisions

While Kharkiv is the administrative centre of the Kharkiv Oblast (province), the city affairs are managed by the Kharkiv Municipality. Kharkiv is a city of oblast subordinance.

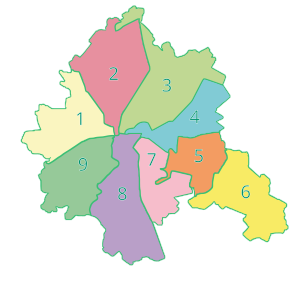

The territory of Kharkiv is divided into 9 administrative raions (districts):

- Leninsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Dzerzhynsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Kyivsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Moskovsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Frunzensky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Ordzhonikidzevsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Kominternіvsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Chervonozavodsky (Template:Lang-uk)

- Zhovtnevy (Template:Lang-uk)

Demographics

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1660[11] | 1,000 |

| 1788[12] | 10,742 |

| 1850[13] | 41,861 |

| 1861[13] | 50,301 |

| 1901[13] | 198,273 |

| 1916[14] | 352,300 |

| 1917[15] | 382,000 |

| 1920[14] | 285,000 |

| 1926[14] | 417,000 |

| 1939[16] | 833,000 |

| 1941[14] | 902,312 |

| 1941[17] | 1,400,000 |

| 1941[14][18] | 456,639 |

| 1943[19] | 170,000 |

| 1959[13] | 930,000 |

| 1962[13] | 1,000,000 |

| 1976[13] | 1,384,000 |

| 1982[12] | 1,500,000 |

| 1989 | 1,593,970 |

| 1999 | 1,510,200 |

| 2001[20] | 1,470,900 |

According to the 1989 Soviet Union Census, the population of the city was 1,593,970. In 1991, the population decreased to 1,510,200, including 1,494,200 permanent city residents.[21] Kharkiv is currently the second-largest city in Ukraine after the capital, Kiev.[2]

The nationality structure of Kharkiv as of the 1989 census is: Ukrainians 50.38%, Russians 43.63%, Jews 3%, Belarusians 0.75%, and all others (more than 25 minorities) 2.24%.[21] according to the Soviet census of 1959 there were Ukrainians (48.4%), Russians (40.4%), Jews (8.7%) and other nationalities (2.5%).[22]

According to the census of 2001 done on the Kharkiv region 53.8% consider Ukrainian as their native tongue, (3.3 % more than in the 1989 census). The Russian language is considered native for 44.3% of the population (a decline of 3.8% since 1989).[23]

Notes

- 1660 year – approximated estimation

- 1788 year – without the account of children

- 1920 year – times of the Russian Civil War

- 1941 year – estimation on May 1, right before the World War II

- 1941 year – next estimation in September varies between 1,400,000 and 1,450,000

- 1941 year – another estimation in December during the occupation without the account of children

- 1943 year – August 23, liberation of the city; estimation varied 170,000 and 220,000

- 1976 year – estimation on June 1

- 1982 year – estimation in March

Economy

During the Soviet era Kharkiv was the capital of industrial production in Ukraine and the third largest centre of industry and commerce in the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union the largely defence-systems-oriented industrial production of the city decreased significantly. In the early 2000s the industry started to recover and adapt to market economy needs. Now there are more than 380 industrial enterprises concentrated in the city, which have a total number of 150,000 employees. The enterprises form machine-building, electro-technologic, instrument-making, and energy conglomerates.

State-owned industrial giants, such as Turboatom[24] and Elektrotyazhmash[25] occupy 17% of the heavy power equipment construction (e.g., turbines) market worldwide. Multipurpose aircraft are produced by the Antonov aircraft manufacturing plant. The Malyshev factory produces not only armoured fighting vehicles, but also harvesters. Khartron[26] is the leading designer of space and commercial control systems in Ukraine and the former CIS.

Kharkiv is also the headquarters of one of the largest Ukrainian banks, UkrSibbank, which has been part of the BNP Paribas group since December 2005.

Science and Education

Kharkiv is one of the most prolific centres of higher education and research of Eastern Europe. The city has 13 national universities and numerous professional, technical and private higher education institutions, offering its students a wide range of disciplines. Kharkiv National University (12,000 students), National Technical University “KhPI” (20,000 students), Kharkiv National Aerospace University "KhAI" ru:Национальный аэрокосмический университет имени Н. Е. Жуковского are the leading universities in Ukraine. A total number of 150,000 students attend the universities and other institutions of higher education in Kharkiv. About 9,000 foreign students from 96 countries study in the city. More than 17,000 faculty and research staff are employed in the institutions of higher education in Kharkiv.

The city has a high concentration of research institutions, which are independent or loosely connected with the universities. Among them are three national science centres: Kharkіv Institute of Physics and Technology,[27] Institute of Metrology,[28] Institute for Experimental and Clinical Veterinary Medicine and 20 national research institutions of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine, such as Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering[29] and Institute for Problems of Cryobiology and Cryomedicine. A total number of 26,000 scientists are working in research and development. A number of world renowned scientific schools appeared in Kharkiv, such as the theoretical physics school and the mathematical school.

In addition to the libraries affiliated with the various universities and research institutions, the Kharkiv State Scientific V. Korolenko-library[30] is a major research library. Kharkiv has 212 (secondary education) schools, including 10 lyceums and 20 gymnasiums.

Modern Kharkiv

Of the many attractions of the Kharkiv city are the: Derzhprom building, Memorial Complex, Freedom Square, Taras Shevchenko Monument, Mirror Stream, Dormition Cathedral, Militia Museum, Annunciation Cathedral, T. Shevchenko Gardens, funicular, Children's narrow-gauge railroad and many more.

Sport

Kharkiv is Ukraine's second-largest city, and as in the whole country sports are taken seriously. The most popular sport is football. The city has several football clubs playing in the Ukrainian National competitions. The most successful is Metalist that also participated in international competitions on numerous occasions.

- Metalist Kharkiv, which plays at the Metalist Stadium

- FC Kharkiv, which plays at the Dynamo Stadium

- FC Helios, which plays at the Helios Arena

- FC Arsenal Kharkiv, which plays at the Arsenal-Spartak Stadium (currently participates in regional competitions)

- HC Kharkiv, which play in the Ukrainian Hockey League

Kharkiv also has a hockey club and a female football club Zhytlobud-1. The last one represented Ukraine in the European competitions and constantly is the main contender for the national title.

RC Olimp' is the city's rugby union club. They are recently the strongest in Ukraine and provide many players for the national team.

Igor Rybak, an Olympic champion lightweight weightlifter, is from Kharkiv.[31]

Culture

Literature

In the 1930s Kharkiv was referred to as a Literary Klondike. It was the centre for the work of literary luminaries such as: Les Kurbas, Mykola Kulish, Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Zerov, Valerian Pidmohylny, Pavlo Filipovych, Marko Voronny, Oleksa Slisarenko. Over 100 of these writers were executed during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. This tragic event in Ukrainian history is called the "Executed Rennaisance" (Rozstrilene vidrodzhennia).

In the 1930s most of these literary figures were repressed. Today a literary museum located on Chervonoprapirna Street marks celebrates their work and achievements.

Kharkiv is the unofficial capital of Ukrainian Science fiction and Fantasy. It is the home to popular writers like H. L. Oldie, Alexander Zorich, Andrey Dashkov, Yuri Nikitin and Andrey Valentinov. Annual science fiction convention "Star Bridge" (Звёздный мост) is held in Kharkiv since 1999.

Music

Kharkiv sponsors the prestigious Hnat Khotkevych International Music Competition of Performers of Ukrainian Folk Instruments which takes place every 3 years. Since 1997 four tri-annual competitions have taken place. The 2010 competition was cancelled by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture 2 days before its opening.[32]

Twin towns – Sister cities

Kharkiv is currently twinned with:[33]

Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia St.Petersburg, Russia

St.Petersburg, Russia Brno, Czech Republic (since 2008)[34]

Brno, Czech Republic (since 2008)[34] Bologna, Italy

Bologna, Italy Lille, France [35]

Lille, France [35] Nürnberg, Germany

Nürnberg, Germany Poznań, Poland [36]

Poznań, Poland [36] Cincinnati, United States

Cincinnati, United States Tianjin, China

Tianjin, China Varna, Bulgaria

Varna, Bulgaria Kaunas, Lithuania

Kaunas, Lithuania Belgorod, Russia

Belgorod, Russia Nizhny Novgorod, Russia

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia Kutaisi, Georgia

Kutaisi, Georgia Jinan, China

Jinan, China Rishon LeZion, Israel

Rishon LeZion, Israel Daugavpils, Latvia

Daugavpils, Latvia

Nobel and Fields prize winners

- Vladimir Drinfel'd (mathematics)

- Simon Kuznets (economics)

- Lev Landau (physics)

- Ilya Mechnikov (biology)

Famous people from Kharkiv

|

|

Transport

The city of Kharkiv is one of the largest transportation centres in Ukraine, which is connected to numerous cities of the world by air, rail and road traffic. The city has many transportation methods, including: public transport, taxis, railways, and air traffic.

Local transport

Being an important transportation centre of Ukraine, Kharkiv itself contains many different transportation methods. Kharkiv's Metro is the city's rapid transit system, operating since 1975, it includes three different lines with 29 stations in total.[37] The Kharkiv buses carry about 12 million passengers annually, trolleybuses, tramways (which celebrated 100 years of service in 2006), and marshrutkas (private minibuses).

Railways

The first railway connection of Kharkiv was opened in 1869. The first train to arrive in Kharkiv came from the north on 22 May 1869, and on 6 June 1869, traffic was opened on the Kursk–Kharkiv–Azov line. Kharkiv's passenger railway station was reconstructed and expanded in 1901, to be later destroyed in the Second World War. A new railway station was built in 1952.

Various railway transportation methods available in the city are the: inter-city railway trains, and elektrichkas (regional electric trains).

Air travel

Kharkiv is served by an international airport which used to have about 200 flights a day, almost all of them being passenger flights. The Kharkiv International Airport was only recently granted international status. The airport itself is not large and is situated within the city boundaries, south from the city centre. Flights to Kiev and Moscow are scheduled daily. There are regular flights to Vienna and Istanbul, and several other destinations. Charter flights are also available. The former largest carrier of the Kharkiv Airport — Aeromost-Kharkiv — is not serving any regular destinations as of 2007. The Kharkiv North Airport is a factory airfield and was a major production facility for Antonov aircraft company.

Gallery

-

T-34 on permanent display near the Historical Museum

-

Autumn in Kharkiv

-

Lord Ganesha in Kharkiv Zoo

-

Kharkiv, Lopan (left) and Kharkiv (right) Rivers

-

Kharkiv Circus

-

New Apartments in Saltivka

-

Dynamovska Street – Bird Eye View

-

Kharkiv State Academy of Culture

-

Cinema Kiev on Marshal Zhukov Avenue, Kharkiv

-

Kharkiv Railway Station – Overhead Bridge View

-

Lopansky Bridge

-

Kharkiv Railway Station

-

Monument Yaroslav the Wise

-

Chapel of Saint Tatiana

Footnotes and references

- ^ Kharkiv on Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b "Results / General results of the census / Number of cities". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ "Weather Information for Kharkov Погода и климат – климат Харькова".

- ^ "Kharkiv weather information".

- ^ [1] Derzhprom statistcs

- ^ Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing by Natalie Kononenko, M.E. Sharp, ISBN 0-7656-0144-3/ISBN 978-0-7656-0144-5, page 116

- ^ Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999–2000, last accessed on 10 December, 2005

- ^ The Red Army committed 765,300 men to this offensive, suffering 277,190 casualties (170,958 killed/missing/PoW, 106,232 wounded) and losing 652 tanks, and 4,924 guns and mortars. Glantz, David M., Kharkov 1942, anatomy of a military disaster through Soviet eyes, pub Ian Allan, 1998, ISBN 0-7110-2562-2 page 218.

- ^ per Robert M. Citino, author of "Death of the Wehrmacht", and other sources, the Red Army came to within a few miles of Kharkiv on 14 May 1942 by Soviet forces under Marshall Timoshenko before being driven back by German forces under Field Marshall Fedor von Bock, p. 100

- ^ In↑ «Сегодня»,21 December 2007.

- ^ Л.И. Мачулин. Mysteries of the underground Kharkov. — Х.: 2005. ISBN 966-8768-00-0 Template:Ru icon

- ^ a b Kharkov: Architecture, monuments, renovations: Travel guide. Ed. А. Лейбфрейд, В. Реусов, А. Тиц. — Х.: Прапор, 1987Template:Ru icon

- ^ a b c d e f Н.Т. Дьяченко. Streets and squares of Kharkov. – X.: Прапор, 1977Template:Ru icon Cite error: The named reference "Дяченко" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e А.В. Скоробогатов. Kharkov in times of German occupation (1941–1943). – X.: Прапор, 2006. ISBN 966-7880-79-6Template:Uk icon Cite error: The named reference "Скоробогатов" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Oleksandr Leibfreid, Yu. Poliakova. Kharkov. From fortress to capital. – Х.: Фолио, 2004Template:Ru icon

- ^ State archives of Kharkov Oblast. Ф. Р-2982, оп. 2, file 16, pp 53–54

- ^ Colonel Н. И. Рудницкий. Военкоматы Харькова в предвоенные и военные годы.Template:Ru icon

- ^ In reference to the German census of December 1941; without children and teenagers no older 16 years of age; numerous city-dwellers evaded the registrationTemplate:Ru icon

- ^ Mykyta Khruschev. Report to ЦК ВКП(б) of August 30, 1943. History: without «white spots». Kharkov izvestia, № 100—101, August 23, 2008, page 6Template:Ru icon

- ^ Ukrainian Census (2001)

- ^ a b "Kharkiv today". Our Kharkіv (in Russian). Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ^ Історія міста Харкова ХХ століття, Харків 2004, р. 456

- ^ [2] Census of 2001

- ^ turboatom.com.ua

- ^ spetm.com.ua

- ^ khartron.com.ua

- ^ Official website of Kharkіv Institute of Physics and Technology

- ^ Official website of Kharkiv Institute of Metrology

- ^ Official website of Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering

- ^ official website of Kharkiv State Scientific V. Korolenko-library

- ^ Volodymyr Kubiĭovych, Danylo Husar Struk (1993). Encyclopedia of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ [3] competition scandal

- ^ "Sister cities of Kharkiv" (in Russian). Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ^ "Brno – Partnerská města" (in Czech). © 2006–2009 City of Brno. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Lile Facts & Figures". Mairie-Lille.fr. Retrieved 2007-12-17. [dead link]

- ^ "Poznań Official Website – Twin Towns".

(in Polish) © 1998–2008 Urząd Miasta Poznania. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

(in Polish) © 1998–2008 Urząd Miasta Poznania. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ "Metro. Basic facts". City transportation Kharkiv (in Ukrainian). Retrieved March 1, 2011.

External links

- General

- night recreation in Kharkiv — Site about recreation in Kharkiv" Template:Uk icon/Template:En icon

- Citynet UA — Official website of Kharkiv City Information Center Template:Uk icon/Template:En icon

- Misto Kharkiv — Official website of Kharkiv City Council Template:Uk icon/Template:En icon

- Vechirniy Kharkiv — Newspaper "Evening Kharkiv" Template:Uk icon/Template:En icon

- Kharkiv city portal Template:Uk icon/Template:Ru icon

- Your beloved Kharkiv — Kharkiv city portal Template:Uk icon/Template:Ru iconTemplate:En icon

- Kharkiv Za Jazz Fest — official web-site of International kharkiv jazz festival KHARKIV ZA JAZZ FEST.

- City transportation of Kharkiv — Transport in Kharkiv Template:Ru icon

- Old Kharkiv Gallery — Photos and postcards

- — 360 VR panoramas of Kharkiv`s square (dinosaur exhibition summer 2010)

- Maps

- Map of Kharkiv — Interactive Map (not active)