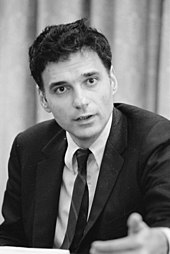

Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader | |

|---|---|

Nader speaking at BYU's Alternate Commencement | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 27, 1934 Winsted, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Political party | Independent |

| Other political affiliations | Green (affiliated non-member) Reform (affiliated non-member) Peace & Freedom (affiliated non-member) Natural Law (affiliated non-member) Populist Party of Maryland (created to support him in 2004) Vermont Progressive Party (affiliated non-member) |

| Alma mater | Princeton University, Harvard University |

| Occupation | Attorney, consumer advocate, and political activist |

| Signature |  |

| Website | nader.org |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1959 |

Ralph Nader (pronounced /ˈneɪdər/; born February 27, 1934)[2][3] is an American progressive political activist, and four-time candidate for President of the United States, having run as a Green Party candidate in 1996 and 2000, and as an independent candidate in 2004 and 2008. He is also an author, lecturer, and attorney.

Areas of particular concern to Nader include consumer protection, humanitarianism, environmentalism, and democratic government.[4]

Nader came to prominence after publishing his book Unsafe At Any Speed, a critique of the safety record of the Chevrolet Corvair automobile. In 1999, an NYU panel of journalists ranked Unsafe At Any Speed 38th among the top 100 pieces of journalism of the 20th century.[5]

In 1990, Life magazine named Nader one of the 100 most influential Americans of the 20th century.[6]

Background and early career

Nader was born in Winsted, Connecticut. His parents, Nathra and Rose Nader, were Maronite Catholic immigrants from Lebanon.[7] His family's native language is Arabic,[7] and he has spoken it along with English since childhood. His sister, Laura Nader, is an anthropologist. His father worked in a textile mill and later owned a bakery and restaurant where he talked politics with his customers.[8]

Nader graduated from The Gilbert School in 1951, followed by Princeton University four years later and then Harvard Law School.[9] He served six months on active duty in the United States Army in 1959, then became a lawyer in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a professor of history and government at the University of Hartford from 1961 to 1963. In 1964, Nader moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan and also advised a United States Senate subcommittee on car safety. Nader has served on the faculty at the American University Washington College of Law.[10][when?]

Automobile safety activism

Nader's first consumer safety articles appeared in the Harvard Law Record, a student publication of Harvard Law School, but he first criticized the automobile industry in an article he wrote for The Nation in 1959 called "The Safe Car You Can't Buy."[11]

In 1965, Nader wrote Unsafe at Any Speed, a book which claimed that many American automobiles were unsafe. The first chapter, "The Sporty Corvair - The One-Car Accident," pertained to the Corvair manufactured by the Chevrolet division of General Motors, which had been involved in accidents involving spins and rollovers. There were over 100 lawsuits pending against GM in connection with accidents involving the popular compact car. These lawsuits provided the initial material for Nader's investigations into the safety of the car.[12]

A 1972 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration safety commission report conducted by Texas A&M University concluded that the 1960–1963 Corvairs possessed no greater potential for loss of control than its contemporaries in extreme situations.[13] Additionally, according to Crash Course by Paul Ingrassia, Corvairs were environmentally friendly due to their smaller size and lighter weight, and Nader's safety-focused activism negatively affected the cause for eco-efficiency.[14] However, former GM executive John DeLorean asserted in On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors (1979) that Nader's criticisms were valid.[15]

In early March 1966, several media outlets, including The New Republic and the New York Times, reported that GM had tried to discredit Nader, hiring private detectives to tap his phones and investigate his past and hiring prostitutes to trap him in compromising situations.[16][17] Nader sued the company for invasion of privacy and settled the case for $284,000. Nader's lawsuit against GM was ultimately decided by the New York Court of Appeals, whose opinion in the case expanded tort law to cover "overzealous surveillance."[18] Nader used the proceeds from the lawsuit to start the pro-consumer Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Nader's advocacy of automobile safety and the publicity generated by the publication of Unsafe at Any Speed, along with concern over escalating nationwide traffic fatalities, contributed to the unanimous passage of the 1966 National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. The act established the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and marked a historic shift in responsibility for automobile safety from the consumer to the manufacturer. The legislation mandated a series of safety features for automobiles, beginning with safety belts and stronger windshields.[19][20][21]

Activism

Hundreds of young activists, inspired by Nader's work, came to DC to help him with other projects. They came to be known as "Nader's Raiders" and, under Nader, investigated government corruption, publishing dozens of books with their results:

- Nader's Raiders (Federal Trade Commission)

- Vanishing Air (National Air Pollution Control Administration)

- The Chemical Feast (Food and Drug Administration)

- The Interstate Commerce Omission (Interstate Commerce Commission)

- Old Age (nursing homes)

- The Water Lords (water pollution)

- Who Runs Congress? (Congress)

- Whistle Blowing (punishment of whistle blowers)

- The Big Boys (corporate executives)

- Collision Course (Federal Aviation Administration)

- No Contest (corporate lawyers)

- Destroy the Forest (Destruction of ecosystems worldwide)

- Operation: Nuclear (Making of a nuclear missile)

In 1971, Nader co-founded the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Public Citizen with fellow public interest lawyer Alan Morrison as an umbrella organization for these projects. Today, Public Citizen has over 225,000 members [22] and investigates congressional, health, environmental, economic and other issues. Nader wrote, "The consumer must be protected at times from his own indiscretion and vanity."[23]

In the 1970s and 1980s Nader was a key leader in the antinuclear power movement. "By 1976, consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who later became allied with the environmental movement, 'stood as the titular head of opposition to nuclear energy'."[24][25] The Critical Mass Energy Project was formed by Nader in 1974 as a national anti-nuclear umbrella group.[26] It was probably the largest national anti-nuclear group in the United States, with several hundred local affiliates and an estimated 200,000 supporters.[27] The organization's main efforts were directed at lobbying activities and providing local groups with scientific and other resources to campaign against nuclear power.[26][28] Nader advocates the complete elimination of nuclear energy in favor of solar, tidal, wind and geothermal, citing environmental, worker safety, migrant labor, national security, disaster preparedness, foreign policy, government accountability and democratic governance issues to bolster his position.[29]

Nader was also a prominent supporter of the Airline Deregulation Act.[30]

Ecology

Nader spent much of 1970 pursuing a campaign to educate the public about ecology. Nader said that the rivers and lakes in America were extremely contaminated. He joked that "Lake Erie is now so contaminated you're advised to have a typhoid inoculation before you set sail on some parts of the lake."[31]

He also added that river's state of contamination affected humans because many residents get their water supply from these contaminated rivers and lakes. "Cleveland takes its water supply from deep in the center of Lake Erie. How much longer is it going to get away with that?"[31]

Nader told how some rivers are contaminated so badly that they can be lit on fire. "The Buffalo River is so full of petroleum residuals, it's been classified an official fire hazard by the City of Buffalo. We have the phenomenon now known as flammable water. The Cuyahoga River outside of Cleveland did catch fire last June, burning a base and some bridges. I often wonder what was in the minds of the firemen as they rushed to the scene of the action and pondered how to put this fire out. But we're heading in river after river: Connecticut River, Hudson River, Mississippi River, you name it. There's some rivers right outside of Boston, New Hampshire and Maine where if a person fell into 'em, I think he would dissolve before he drowned."[31]

Non-profit organizations

Throughout his career, Nader has started or inspired a variety of nonprofit organizations, most of which he has maintained close associations with:

|

|

In 1980, Nader resigned as director of Public Citizen to work on other projects, lecturing on the growing "imperialism" of multinational corporations and of a dangerous convergence of corporate and government power.[32]

Presidential campaigns

Ralph Nader has been a frequent contender in U.S. presidential elections, always as an independent candidate or a third party nominee. His activism on behalf of third parties goes back to 1958, when he wrote an article for the Harvard Law Record critiquing U.S. electoral law's systemic discrimination against them.[33]

Presidential campaign history

1972

Ralph Nader's name appeared in the press as a potential candidate for president for the first time in 1971, when he was offered the opportunity to run as the presidential candidate for the New Party, a progressive split-off from the Democratic Party in 1972. Chief among his advocates was author Gore Vidal, who touted a 1972 Nader presidential campaign in a front-page article in Esquire magazine in 1971.[34] Psychologist Alan Rockway organized a "draft Ralph Nader for President" campaign in Florida on the New Party's behalf.[35] Nader declined their offer to run that year; the New Party ultimately joined with the People's Party in running Benjamin Spock in the 1972 Presidential election.[36][37][38] Spock had hoped Nader in particular would run, getting "some of the loudest applause of the evening" when mentioning him at the University of Alabama.[39] Spock went on to try to recruit Nader for the party among over 100 others, and indicated he would be "delighted" to be replaced by any of them even after he accepted the nomination himself.[40] Nader received one vote for the vice-presidential nomination at the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

1992

Nader stood in as a write-in for "none of the above" in both the 1992 New Hampshire Democratic and Republican Primaries[41] and received 3,054 of the 170,333 Democratic votes and 3,258 of the 177,970 Republican votes cast.[42] He was also a candidate in the 1992 Massachusetts Democratic Primary, where he appeared at the top of the ballot (in some areas, he appeared on the ballot as an independent).

1996

Nader was drafted as a candidate for President of the United States on the Green Party ticket during the 1996 presidential election. He was not formally nominated by the Green Party USA, which was, at the time, the largest national Green group; instead he was nominated independently by various state Green parties (in some states, he appeared on the ballot as an independent). However, many activists in the Green Party USA worked actively to campaign for Nader that year. Nader qualified for ballot status in 22 states,[43] garnering 685,297 votes or 0.71% of the popular vote (fourth place overall),[44] although the effort did make significant organizational gains for the party. He refused to raise or spend more than $5,000 on his campaign, presumably to avoid meeting the threshold for Federal Elections Commission reporting requirements; the unofficial Draft Nader committee could (and did) spend more than that, but the committee was legally prevented from coordinating in any way with Nader himself.

Nader received some criticism from gay rights supporters for calling gay rights "gonad politics" and stating that he was not interested in dealing with such matters.[45] However, more recently, Nader has come out in support of same-sex marriage.[46]

His 1996 running mates included: Anne Goeke (nine states), Deborah Howes (Oregon), Muriel Tillinghast (New York), Krista Paradise (Colorado), Madelyn Hoffman (New Jersey), Bill Boteler (Washington, D.C.), and Winona LaDuke (California and Texas).[47]

2000

In the 2006 documentary An Unreasonable Man, Nader describes how he was unable to get the views of his public interest groups heard in Washington, even by the Clinton Administration. Nader cites this as one of the primary reasons that he decided to actively run in the 2000 election as candidate of the Green Party, which had been formed in the wake of his 1996 campaign.

In June 2000 The Association of State Green Parties (ASGP) organized the national nominating convention that took place in Denver, Colorado, at which Greens nominated Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke to be their parties` candidates for President and Vice President.[48][49]

On July 9, the Vermont Progressive Party nominated Nader, giving him ballot access in the state.[50] On August 12, the United Citizens Party of South Carolina chose Ralph Nader as its presidential nominee, giving him a ballot line in the state.[51]

In October 2000, at the largest Super Rally of his campaign,[52] held in New York City's Madison Square Garden, 15,000 people paid $20 each[53] to hear Mr. Nader speak. Nader's campaign rejected both parties as institutions dominated by corporate interests, stating that Al Gore and George W. Bush were "Tweedledee and Tweedledum". A long list of notable celebrities spoke and performed at the event including Susan Sarandon, Ani DiFranco, Ben Harper, Tim Robbins, Michael Moore, Eddie Vedder and Patti Smith. The campaign also had some prominent union help: The California Nurses Association and the United Electrical Workers endorsed his candidacy and campaigned for him.[54]

In 2000, Nader and his running mate Winona LaDuke received 2,883,105 votes, for 2.74 percent of the popular vote (third place overall),[55] missing the 5 percent needed to qualify the Green Party for federally distributed public funding in the next election, yet qualifying the Greens for ballot status in many states.

Nader's votes in New Hampshire and Florida vastly exceeded the difference in votes between Gore and Bush, as did the votes of all alternative candidates.[56] Exit polls showed New Hampshire staying close, and within the margin of error without Nader[57] as national exit polls showed Nader's supporters choosing Gore over Bush by a large margin,[58] well outside the margin of error. Winning either state would have given Gore the presidency, and while critics claim this shows Nader tipped the election to Bush, Nader has called that claim "a mantra — an assumption without data."[59] Nader supporters argued that Gore was primarily responsible for his own loss.[60] But Eric Alterman, perhaps Nader's most persistent critic, has regarded such arguments as beside the point: "One person in the world could have prevented Bush's election with his own words on the Election Day 2000."[61] Nation columnist Alexander Cockburn cited Gore's failure to win over progressive voters in Florida who chose Nader, and congratulated those voters: "Who would have thought the Sunshine State had that many progressives in it, with steel in their spine and the spunk to throw Eric Alterman's columns into the trash can?"[62] Nader's actual influence on the 2000 election is the subject of considerable discussion, and there is no consensus on Nader's impact on the outcome. Still others argued that even if Nader's constituents could have made the swing difference between Gore and Bush, the votes Nader garnered were not from the Democrats, but from Democrats, Republicans, and discouraged voters who would not have voted otherwise.[63]

The "spoiler" controversy

In the 2000 presidential election in Florida, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by 537 votes. Nader received 97,421 votes, which led to claims that he was responsible for Gore's defeat. Nader, both in his book Crashing the Party and on his website, states: "In the year 2000, exit polls reported that 25% of my voters would have voted for Bush, 38% would have voted for Gore and the rest would not have voted at all."[64] (which would net a 13%, 12,665 votes, advantage for Gore over Bush.) Michael Moore at first argued that Florida was so close that votes for any of seven other candidates could also have switched the results,[65] but in 2004 joined the view that Nader had helped make Bush president.[66][67] When asked about claims of being a spoiler, Nader typically points to the controversial Supreme Court ruling that halted a Florida recount, Gore's loss in his home state of Tennessee, and the "quarter million Democrats who voted for Bush in Florida."[68][69]

A study in 2002 by the Progressive Review found no correlation in pre-election polling numbers for Nader when compared to those for Gore. In other words, most of the changes in pre-election polling reflect movement between Bush and Gore rather than Gore and Nader, and they conclude from this that Nader was not responsible for Gore's loss.[70]

An analysis conducted by Harvard Professor B.C. Burden in 2005 showed Nader did "play a pivotal role in determining who would become president following the 2000 election", but that:

"Contrary to Democrats’ complaints, Nader was not intentionally trying to throw the election. A spoiler strategy would have caused him to focus disproportionately on the most competitive states and markets with the hopes of being a key player in the outcome. There is no evidence that his appearances responded to closeness. He did, apparently, pursue voter support, however, in a quest to receive 5% of the popular vote."[71]

However, Jonathan Chait of The American Prospect and The New Republic notes that Nader did indeed focus on swing states disproportionately during the waning days of the campaign, and by doing so jeopardized his own chances of achieving the 5% of the vote he was aiming for.

Then there was the debate within the Nader campaign over where to travel in the waning days of the campaign. Some Nader advisers urged him to spend his time in uncontested states such as New York and California. These states – where liberals and leftists could entertain the thought of voting Nader without fear of aiding Bush – offered the richest harvest of potential votes. But, Martin writes, Nader – who emerges from this account as the house radical of his own campaign – insisted on spending the final days of the campaign on a whirlwind tour of battleground states such as Pennsylvania and Florida. In other words, he chose to go where the votes were scarcest, jeopardizing his own chances of winning 5 percent of the vote, which he needed to gain federal funds in 2004.[72]

When Nader, in a letter to environmentalists, attacked Gore for "his role as broker of environmental voters for corporate cash," and "the prototype for the bankable, Green corporate politician," and what he called a string of broken promises to the environmental movement, Sierra Club president Carl Pope sent an open letter to Nader, dated 27 October 2000, defending Al Gore's environmental record and calling Nader's strategy "irresponsible."[73] He wrote:

You have also broken your word to your followers who signed the petitions that got you on the ballot in many states. You pledged you would not campaign as a spoiler and would avoid the swing states. Your recent campaign rhetoric and campaign schedule make it clear that you have broken this pledge... Please accept that I, and the overwhelming majority of the environmental movement in this country, genuinely believe that your strategy is flawed, dangerous and reckless.[74]

2004

Nader announced on December 24, 2003, that he would not seek the Green Party's nomination for president in 2004, but did not rule out running as an independent candidate.

Meeting with John Kerry

Ralph Nader and Democratic candidate John Kerry held a widely publicized meeting early in the 2004 Presidential campaign, which Nader described in An Unreasonable Man. Nader said that John Kerry wanted to work to win Nader's support and the support of Nader's voters. Nader then provided more than 20 pages of issues that he felt were important and he "put them on the table" for John Kerry. According to Nader the issues covered topics ranging from environmental, labor, healthcare, tax reform, corporate crime, campaign finance reform and various consumer protection issues. Nader reported that he asked John Kerry to choose any three of the issues and highlight them in his campaign and if Kerry would do this, he would refrain from the race. For example, Nader recommended taking up corporate welfare, corporate crime—which could attract many Republican voters, and labor law reform—which was felt Bush could never support given the corporate funding of his campaign.[75] Several days passed and Kerry failed to adopt any of Nader's issues as benchmarks of his campaign, so on February 22, 2004, Nader announced on NBC that he would indeed run for president as an independent, saying, "There's too much power and wealth in too few hands."

A Kerry aide who had attended the meeting had a different recollection. "He made more the point that he had the ability to go after Bush in ways that we could not, He did not at all say to Kerry, 'I'm here to make you better on things.' That was not his tone at all."

The New York Times quoted Nader saying after the meeting "Gore was petrified wood, He was stiff as a board, he didn't want to have these kinds of meetings. He didn't want to have meetings like this when he was vice president three years before the election. Kerry is much more open." Nader himself said he had deliberately steered clear of disagreement, telling the Times, "When you go in looking for common ground, it takes up most of the time, doesn't it?"[76]

The campaign

Nader's 2004 campaign ran on a platform consistent with the Green Party's positions on major issues, such as opposition to the war in Iraq. He has detailed the legal reasons George W. Bush and Dick Cheney fit the criteria for war criminals, and why they should have been immediately impeached.[77]

Due to concerns about a possible spoiler effect as in 2000, many Democrats urged Nader to abandon his 2004 candidacy. The Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Terry McAuliffe, stated that Nader had a "distinguished career, fighting for working families," and that McAuliffe "would hate to see part of his legacy being that he got us eight years of George Bush." Nader replied to this, in filmed interviews for An Unreasonable Man, by arguing that, "Voting for a candidate of one's choice is a Constitutional right, and the Democrats who are asking me not to run are, without question, seeking to deny the Constitutional rights of voters who are, by law, otherwise free to choose to vote for me." Nader's 2004 campaign theme song was "If You Gotta Ask" by Liquid Blue.

In May 2009, in a new book, Grand Illusion: The Myth of Voter Choice in a Two-Party Tyranny, Theresa Amato, who was Nader's national campaign manager in 2000 and 2004, alleged that McAuliffe offered to pay off Nader to stop campaigning in certain states in 2004. This was confirmed by Nader, and neither McAuliffe nor his spokeswoman disputed the claim.[78]

In the 2004 campaign, Democrats such as Howard Dean and Terry McAuliffe asked that Nader return money donated to his campaign by Republicans who were well-known Bush supporters, such as billionaire Richard Egan.[79][80] Nader's reaction to the request was to refuse to return any donations and he charged that the Democrats were attempting to smear him.[79] Nader's vice-presidential running mate, Peter Camejo, supported the return of the money if it could be proved that "the aim of the wealthy GOP donors was to peel votes from Kerry."[79] According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Nader defended his keeping of the donations by saying that wealthy contributors "are human beings too."[79]

Nader received 463,655 votes, for 0.38 percent of the popular vote, placing him in third place overall.[81]

2008

Template:Wikinewspar2 In February 2007, Nader criticized Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton as "a panderer and a flatterer."[82] Asked on CNN Late Edition news program if he would run in 2008, Nader replied, "It's really too early to say...."[83] Asked during a radio appearance to describe the former First Lady, Nader said, "Flatters, panders, coasting, front-runner, looking for a coronation ... She has no political fortitude."[84] Some Greens started a campaign to draft Nader as their party's 2008 presidential candidate.[85]

After some consideration, Nader announced on February 24, 2008, that he would run for President as an independent. His vice-presidential candidate was Matt Gonzalez.[86]

Nader received 738,475 votes, for 0.56 percent of the popular vote, earning him a third place position in the overall election results.[87]

Personal life

Nader has never married. Karen Croft, a writer who worked for Nader in the late 1970s at the Center for Study of Responsive Law, once asked him if he had ever considered getting married. "He said that at a certain point he had to decide whether to have a family or to have a career, that he couldn't have both," Croft recalled. "That's the kind of person he is. He couldn't have a wife — he's up all night reading the Congressional Record."[88]

He has been described as a Christian by The Washington Post, though, as with most aspects of his personal life, Nader does not discuss his religion.[89]

Personal finances

According to the mandatory fiscal disclosure report that he filed with the Federal Election Commission in 2000, Nader owned more than $3 million worth of stocks and mutual fund shares; his single largest holding was more than $1 million worth of stock in Cisco Systems, Inc. He also held between $100,000 and $250,000 worth of shares in the Magellan Fund.[90] Nader owned no car or real estate directly in 2000, and said that he lived on US $25,000 a year, giving most of his stock earnings to many of the over four dozen non-profit organizations he had founded.[91][92]

Television appearances

In 1988, Nader appeared on Sesame Street as "a person in your neighborhood." The verse of the song began "A consumer advocate is a person in your neighborhood." Nader's appearance on the show was memorable because it was the only time that the grammar of the last line of the song—"A person who you meet each day"—was questioned and changed in the show. Nader refused to sing the prescriptively improper line, and so a compromise was reached, resulting in Ralph Nader singing the last line as a solo with the modified words: "A person whom you meet each day."[93] In the same episode, Nader tests "Bob"'s sweater, with permission, and destroys it, telling Bob "Your aunt . . . knitted you a lemon!"

He hosted an episode of NBC's Saturday Night Live in 1977 and appeared in a 2000 episode.[citation needed]

He was interviewed on Da Ali G Show by Sacha Baron Cohen.[citation needed]

During his 2008 presidential campaign, Nader appeared on NBC's Meet The Press, CNBC with John Harwood, CNN with Rick Sanchez, PBS's The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, and Fox News Channel with Shepard Smith.[94] He was interviewed by Triumph the Insult Comic Dog on Late Night with Conan O'Brien in 2008. Also that year he appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher. In 2011, he appeared multiple times on the Fox Business Network primetime show Freedom Watch with Andrew Napolitano, including a January 19, 2011 joint appearance with Ron Paul.[citation needed]

Works

See also

Notes

- An Unreasonable Man (2006). An Unreasonable Man is a documentary film about Ralph Nader that appeared at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival.

- Burden, Barry C. (2005). Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election 2005, American Politics Research 33:672-99.

- Ralph Nader: Up Close This film blends archival footage and scenes of Nader and his staff at work in Washington with interviews with Nader's family, friends and adversaries, as well as Nader himself. Written, directed and produced by Mark Litwak and Tiiu Lukk, 1990, color, 72 mins. Narration by Studs Terkel. Broadcast on PBS. Winner, Sinking Creek Film Festival; Best of Festival, Baltimore Int'l Film Festival; Silver Plaque, Chicago Int'l Film Festival, Silver Apple, National Educational Film & Video Festival.

- Bear, Greg, "Eon" — the novel includes a depiction of a future group called the "Naderites" who follow Ralph Nader's humanistic teachings.

- Martin, Justin. Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon. Perseus Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-7382-0563-X

References

- ^ Ralph Nader Bio. The Washington Post. 2005. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "Ralph Nader Biography – Academy of Achievement". Achievement.org. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ "Ralph Nader Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ "Seth Gitell "The Green Party gets serious" ''The Providence Phoenix'' June 29, 2000". Providencephoenix.com. 2000-07-06. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (1999-03-01). "MEDIA; Journalism's Greatest Hits: Two Lists of a Century's Top Stories". NY Times. p. 2.

- ^ Deparle, Jason (1990-09-21). "Washington at Work; Eclipsed in the Reagan Decade, Ralph Nader Again Feels Glare of the Public". NY Times.

- ^ a b "Ralph Nader's Childhood Roots".

- ^ Mantel, Henriette (Director) (2006). An Unreasonable Man (DVD). IFC Films.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|title= - ^ "2004 Presidential Candidates — Ralph Nader". CNN.com Specials.

- ^ "Washington College of Law Faculty".

- ^ Mickey Z. 50 American Revolutions You're Not Supposed To Know. New York: The Disinformation Company, 2005. p.87 ISBN 1-932857-18-4

- ^ Diana T. Kurylko. "Nader Damned Chevy's Corvair and Sparked a Safety Revolution." Automotive News (v.70, 1996).

- ^ Brent Fisse and John Braithwaite, The Impact of Publicity on Corporate Offenders. State University of New York Press, 1983. p.30 ISBN 0-87395-733-4

- ^ Ingrassia, Paul (2010). Crash Course: The American Automobile Industry's Road from Glory to Disaster. New York: Random House. ISBN 9781400068630.

- ^ Wright, J. V.; De Lorean, John Z. (1979). On a clear day you can see General Motors. Grosse Pointe, Mich: Wright Enterprises. ISBN 0-9603562-0-7.

- ^ "Ralph Nader's museum of tort law will include relics from famous lawsuits—if it ever gets built". LegalAffairs.org. December 2005.

- ^ "President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Federal Role in Highway Safety: Epilogue — The Changing Federal Role". Federal Highway Administration. 2005-05-07.

- ^ Nader v. General Motors Corp., 307 N.Y.S.2d 647 (N.Y. 1970)

- ^ Brent Fisse and John Braithwaite. The Impact of Publicity on Corporate Offenders. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1983.

- ^ Robert Barry Carson, Wade L. Thomas, Jason Hecht. Economic Issues Today: Alternative Approaches. M.E. Sharpe, 2005.

- ^ Stan Luger. Corporate Power, American Democracy, and the Automobile Industry. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ Weissman, Robert (2011-01-05), Letter to Darrell Issa http://www.citizen.org/documents/Issa-Letter-20110105.pdf

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sowell, Thomas (2004-03-03), "Nader's Glitter", Jewish World Review

- ^ Nuclear Power in an Age of Uncertainty (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-E-216, February 1984), p. 228, citing the following article:

- ^ Public Opposition to Nuclear Energy: Retrospect and Prospect, Roger E. Kasperson, Gerald Berk, David Pijawka, Alan B. Sharaf, James Wood, Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 5, No. 31 (Spring, 1980), pp. 11–23

- ^ a b Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 402.

- ^ Steve Cohn (1997). Too cheap to meter: an economic and philosophical analysis of the nuclear dream SUNY Press, pp. 133-134.

- ^ Justin Martin (2002). Nader, Perseus Publishing, pp. 172-179.

- ^ "Ralph Nader interview transcript". Frontline.

- ^ Thierer, Adam (2010-12-21) Who'll Really Benefit from Net Neutrality Regulation?, CBS News

- ^ a b c "Ecology: 1970 Year in Review", UPI.com.

- ^ "The Nader Page | History". Nader.org. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ Two party ballot suppresses third party change, including an excerpt from Nader's 1958 article and analyzing the lack of change in ballot access law since. Published in the Harvard Law Record, December 2009

- ^ Vidal, Gore The Best Man/'72, Esquire

- ^ "Coalition Party Opens Conference". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. October 2, 1971. pp. 2A.

- ^ Gore Vidal. "The Best Man /'72: Ralph Nader Can Be President of the US." Esquire, June, 1971.

- ^ Peter Barnes. "Toward '72 and Beyond: Starting a Fourth Party". The New Republic, July 24–31, 1971:9–21

- ^ Justin Martin. "Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon". Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-7382-0563-X.

- ^ Smithey, Waylon (September 23, 1971). "Spock Shares Youths' Views". The Tuscaloosa News. p. 2.

- ^ "People's Party Nominates Dr. Spock for President". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. November 29, 1971. pp. B5.

- ^ The 1992 Campaign: Write-In; In Nader's Campaign, White House Isn't the Goal February 18, 1992

- ^ "1992 Presidential Primary". Sos.nh.gov. 1992-02-18. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Politics1.com". Politics1.com. 1934-02-27. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Uselectionatlas.org". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Leftbusinessobserver.com". Leftbusinessobserver.com. 1984-06-28. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Votenader.org". Votenader.org. 2001-09-11. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Ecological Politics: Ecofeminists and the Greens By Greta Gaard, page 240.

- ^ Common Dreams Progressive Newswire (July 11, 2001). Green Meeting Will Establish Greens as a National Party. Retrieved 8-28-2009.

- ^ Nelson, Susan. Synthesis/Regeneration 26 (Fall 2001).The G/GPUSA Congress and the ASGP Conference: Authentic Grassroots Democracy vs. Packaged Public Relations. Retrieved 8-28-2009.

- ^ Ballot Access News (Aug. 1, 2000). PROGRESSIVES NOMINATE NADER

- ^ (2000-08-01) United Citizens Party Picks Nader, Ballot Access News.

- ^ "Nader 'Super Rally' Draws 12,000 To Boston's FleetCenter". Commondreams.org. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ CNN.com – Loyal Nader fans pack Madison Square Garden – October 14, 2000[dead link]

- ^ "Nader, the Greens and 2008". Socialistworker.org. 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/national.php?year=2000

- ^ U.S. Federal Election Commission. 2000 Official Presidential General Election Results.

- ^ MSNBC. Decision 2000

- ^ Rosenbaum, David E. (2004-02-24). "THE 2004 CAMPAIGN: THE INDEPENDENT; Relax, Nader Advises Alarmed Democrats, but the 2000 Math Counsels Otherwise". The New York Times.

- ^ Vedantam, Shankar (2004-02-23). "Democrats Upset at 'Spoiler' in 2000 Race". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "S/R 25: Gore's Defeat: Don't Blame Nader (Marable)". Greens.org. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Ralph Nader on Jon Stewart". Huffingtonpost.com. 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Alexander Cockburn. "The Best of All Possible Worlds." The Nation.November 9, 2000.

- ^ "Don't Believe The Hype: Nader Did Not Cost Gore The Election". Sobriquetmagazine.com. 2008-06-19. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Dear Conservatives Upset With the Policies of the Bush Administration". Nader for President 2004.

- ^ "Michael Moore message". Michaelmoore.com. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (2004-07-28). "The Constituencies: Liberals; From Chicago '68 to Boston, The Left Comes Full Circle". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Convictions Intact, Nader Soldiers On – New York Times[dead link]

- ^ Varadarajan, Tunku (2008-05-31). "Interview: Ralph Nader". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Nader on the Record". Grist. 2008-03-19.

- ^ "Poll Analysis: Nader not responsible for Gore's loss".

- ^ Burden, B. C. (September 2005). "Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy" (PDF). American Politics Research: 673–699.

- ^ "Books in Review: | The American Prospect". Prospect.org. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ knowthecandidates.org.The Nader Debate with the Sierra Club about Gore and the Environment

- ^ Pope, Carl (October 27, 2000)"Ralph Nader Attack On Environmentalists Who Are Supporting Vice-President Gore." CommonDreams.org.

- ^ An Unreasonable Man, Ral

- ^ "Kerry Woos Nader, Who Declares Him 'Very Presidential' – New York Times". Nytimes.com. 2004-05-20. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ Kugel, Allison (October 22, 2009). "Howard Dean Talks Healthcare Reform in the Age of Hardcore Party Politics". PR.com. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ Kumar, Anita; Helderman, Rosalind S. (2009-05-29). "Nader: McAuliffe Offered Money To Avoid Key States in '04 Race". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ a b c d "Nader defends GOP Cash". Carla Marinucci. San Francisco Chronicle. July 10, 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ "Nader Republicans". Nathan Littlefield. Atlantic Monthly. September 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. "2004 Presidential General Election Results". Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ^ Winter, Michael (February 5, 2007). "Nader in '08? Stay tuned". USA Today (Online). Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ^ Nader Leaves '08 Door Open, Slams Hillary Reuters, February 5, 2007.

- ^ Ralph Nader: Hillary's Just a 'Bad Version of Bill Clinton' Feb. 16, 2007

- ^ "DraftNader.org". DraftNader.org. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Nader names running mate in presidential bid". CBC News. 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "2008 Official Presidential General Election Results" (PDF). FEC. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Candidate Nader", Mother Jones. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ "Washingtonpost.com". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (28 October 2000). "Inside Nader's stock portfolio". Salon. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Nader Reports Big Portfolio In Technology". New York Times. 2000-06-19. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Ralph Nader: Personal Finances". Center for Responsive Politics. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ David Borgenicht, Sesame Street Unpaved: Scripts, Stories, Secrets, and Songs, 1998 and 2002 reprint, ISBN 1-4028-9327-2

- ^ "Nader on CNN, FOX, CNBC and PBS NewsHour Tuesday". Nader for President 2008. 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

Further reading

- What Was Ralph Nader Thinking? by Jurgen Vsych, Wroughten Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9749879-2-7

- Abuse of Trust: A Report on Ralph Nader's Network by Dan Burt, 1982. ISBN 978-0-89526-661-3

- Citizen Nader by Charles McCarry Saturday Review Press, 1972 ISBN 0-8415-0163-7

- The Investigation of Ralph Nader by Thomas Whiteside 1972.

External links

- Nader.org official website

- Nader / Gonzalez '08 campaign website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ralph Nader on Charlie Rose

- Ralph Nader at IMDb

- Template:Worldcat id

- Ralph Nader collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Template:Nndb

- Articles and interviews

- Kugel, Allison (May 14, 2008). "Ralph Nader Goes to Washington... Again - The PR.com Interview". PR.com.

- "How Winstedites Kept Their Integrity," article by Nader in the September 1963 issue of The Freeman

- Ralph Nader Goes to Washington... Again – The PR.com Interview

- Digital History Ralph Nader

- Nader, Rare Among Candidates May 5, 2008

- Ralph Nader

- American anti-Iraq War activists

- American anti-nuclear power activists

- American democracy activists

- American environmentalists

- American non-fiction environmental writers

- American political writers

- American University faculty and staff

- American politicians of Lebanese descent

- American social democrats

- Anti-corporate activists

- American Maronites

- Arab Christians

- Connecticut lawyers

- Consumer rights activists

- Drug policy reform activists

- Green Party (United States) presidential nominees

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Independent politicians in the United States

- People from Winchester, Connecticut

- People from Winsted, Connecticut

- Princeton University alumni

- Reform Party of the United States of America politicians

- United States presidential candidates, 1992

- United States presidential candidates, 1996

- United States presidential candidates, 2000

- United States presidential candidates, 2004

- United States presidential candidates, 2008

- University of Hartford faculty

- Youth empowerment individuals

- Youth rights individuals

- 1934 births

- Living people