Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

Dwight Eisenhower in 1959. | |

| 34th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 | |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Succeeded by | John F. Kennedy |

| 1st Supreme Allied Commander Europe | |

| In office April 2, 1951 – May 30, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Post Created |

| Succeeded by | Gen. Matthew Ridgway |

| 1st Military Governor of the American Occupation Zone in Germany | |

| In office May 8 – November 10, 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Post Created |

| Succeeded by | Gen. George Patton (acting) |

| 13th President of Columbia University | |

| In office 1948–1953 | |

| Preceded by | Frank D. Fackenthal |

| Succeeded by | Grayson L. Kirk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | David Dwight Eisenhower October 14, 1890 Denison, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 1969 (aged 78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mamie Doud Eisenhower |

| Children | Doud Dwight Eisenhower, John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower |

| Alma mater | U.S. Military Academy West Point, New York, United States |

| Occupation | Army Officer |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal with four oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Order of the Southern Cross, Order of the Bath, Order of Merit, Legion of Honor (partial list) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1953, 1961–1969[1] |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Europe |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈaɪzənhaʊər/ EYE-zən-how-ər; October 14, 1890– March 28, 1969) was a five-star general in the United States Army and the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961, and the last to be born in the 19th century. During World War II, he served as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe, with responsibility for planning and supervising the successful invasion of France and Germany in 1944–45, from the Western Front. In 1951, he became the first supreme commander of NATO.[2]

A Republican, Eisenhower entered the 1952 presidential race to counter the non-interventionism of Sen. Robert A. Taft, and to crusade against "Communism, Korea and corruption". He won by a landslide, defeating Democrat Adlai Stevenson and ending two decades of the New Deal Coalition holding the White House. As President, Eisenhower concluded negotiations with China to end the Korean War. His New Look, a policy of nuclear deterrence, gave priority to inexpensive nuclear weapons while reducing the funding for the other military forces to keep pressure on the Soviet Union and reduce federal deficits at the same time. He began NASA to compete against the Soviet Union in the space race. His intervention during the Suez Crisis was later acknowledged by Eisenhower himself as his greatest foreign policy mistake. Near the end of his term, the Eisenhower Administration was embarrassed by the U-2 incident and was planning the Bay of Pigs invasion.

On the domestic front, he covertly helped remove Joseph McCarthy from power but otherwise left most political actions to his Vice President, Richard Nixon. He was a moderate conservative who continued the New Deal policies, and in fact enlarged the scope of Social Security, and signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. Though passive on civil rights at first, he sent federal troops to enforce the Supreme Court's ruling to desegregate schools. He was the first term-limited president in accordance with the 22nd Amendment.

Eisenhower's two terms were mainly peaceful, and generally prosperous except for a sharp economic recession in 1958–59. Although public approval for his administration was comparatively low by the end of his term, his reputation improved over time and in recent surveys of historians, Eisenhower is often ranked as one of the top ten U.S. Presidents.

Family, early life and education

The Eisenhauer (German for "iron striker") family migrated from Germany to Switzerland in the 17th century due to religious persecution, and a century later came to the United States. A misspelling in official documents changed their name, and the Eisenhower family lived in York, Pennsylvania from 1730 to the 1880s, when they moved to Kansas.[3] Eisenhower's father, David Jacob Eisenhower (1863–1942) was a college-educated engineer but had trouble making a living and the family was poor.[4] Eisenhower's mother, Ida Elizabeth Stover, born in Virginia of German Lutheran ancestry, moved to Kansas from Virginia. She married David Jacob on September 23, 1885 in Lecompton, Kansas on the campus of their alma mater, Lane University. The family lived in Texas from 1889 until 1892, then returned to Kansas. Eisenhower was born on October 14, 1890, in Denison, Texas, the third of seven boys.[5] All of the boys were called "Ike", "Big Ike", "Little Ike", or (in Eisenhower's case) "Ugly Ike" during their lives, but the nickname's origin is a mystery; by World War II only Eisenhower was still called "Ike".[3] In 1892 the family moved to Abilene, Kansas,[6] which Eisenhower considered as his home town.[3] He graduated from Abilene High School in 1909.[7] Though born David, he was called Dwight, so he reversed the order of his given names when he enrolled at the United States Military Academy in 1911,[8] and received his commission as a second lieutenant in 1915.[3]

Eisenhower met Mamie Geneva Doud of Boone, Iowa while he was stationed in Texas.[3] They married on July 1, 1916, in Denver, and had two sons. Doud Dwight Eisenhower was born September 24, 1917, and died of scarlet fever on January 2, 1921, at the age of three.[9] Their second son, John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower, was born on August 3, 1922; John served in the United States Army, retiring as a brigadier general, became an author, and served as U.S. Ambassador to Belgium from 1969 to 1971. John, coincidentally, graduated from West Point on D-Day, June 6, 1944. He married Barbara Jean Thompson on June 10, 1947. John and Barbara had four children: Dwight David II "David", Barbara Ann, Susan Elaine and Mary Jean. David, after whom Camp David is named, married Richard Nixon's daughter Julie in 1968.

When Eisenhower was a child, his mother Ida Elizabeth Stover Eisenhower, previously a member of the River Brethren sect of the Mennonites, joined the International Bible Students Assocation, which would evolve into what is now known as Jehovah's Witnesses. The Eisenhower home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915 but Eisenhower never joined the International Bible Students.[10] His decision to attend West Point saddened his mother, who felt that warfare was "rather wicked," but she did not overrule him.[11] Eisenhower was baptized in the Presbyterian Church in 1953. In 1948, he had called himself "one of the most deeply religious men I know" though unattached to any "sect or organization".[12]

Eisenhower attended Abilene High School in Abilene, Kansas and graduated with the class of 1909.[7] He was then employed as a night foreman at the Belle Springs Creamery.[13] After Eisenhower worked for two years to support his brother Edgar's college education, a friend urged him to apply to the Naval Academy. Though Eisenhower passed the entrance exam, he was beyond the age of eligibility for admission to the Naval Academy.[14] Kansas Senator Joseph L. Bristow recommended Eisenhower for an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York in 1911, which he received.[14] Eisenhower graduated in the upper half of the class of 1915,[15] which became known as "the class the stars fell on", because 59 members eventually became general officers.

Athletic career

Eisenhower later said that "not making the baseball team at West Point was one of the greatest disappointments of my life, maybe my greatest."[16] However he did make the football team, and was a varsity starter as running back and linebacker in 1912, tackling the legendary Jim Thorpe of the Carlisle Indians that year.[17] Eisenhower broke his leg that game, however, and it became permanently damaged on horseback and in the boxing ring,[3][18] so he turned to fencing and gymnastics.[3] Eisenhower would later serve as junior varsity football coach and yell leader.[19] In 1916, while stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Eisenhower was football coach for St. Louis College, now St. Mary's University.[20][21]

Eisenhower played golf very enthusiastically later in life, and joined the Augusta National Golf Club in 1948.[22] He played golf frequently during his two terms as president, and after his retirement as well, never shying away from the media interest about his passion for golf. He had a small, basic golf facility installed at Camp David, and became close friends with Augusta National Chairman Clifford Roberts, inviting Roberts to stay at the White House on several occasions; Roberts, an investment broker, also handled the Eisenhower family's investments. Roberts also advised Eisenhower on tax aspects of publishing his memoirs, which proved to be financially lucrative.[22]

Early military career

Eisenhower enrolled at the United States Military Academy at West Point in June 1911. His parents, who were against militarism, did not object to his entering West Point because they supported his education. Eisenhower was a strong athlete and enjoyed notable successes in his competitive endeavors.

Eisenhower graduated in 1915. He served with the infantry until 1918 at various camps in Texas and Georgia. During World War I, Eisenhower became the #3 leader of the new tank corps and rose to temporary (Bvt.) Lieutenant Colonel in the National Army. During the war he trained tank crews at "Camp Colt"—his first command—on the grounds of "Pickett's Charge" on the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania Civil War battle site. Ike and his tank crews never saw combat. After the war, Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of captain (and was promoted to major a few days later) before assuming duties at Camp Meade, Maryland, where he remained until 1922. His interest in tank warfare was strengthened by many conversations with George S. Patton and other senior tank leaders; however their ideas on tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors.[23]

Eisenhower became executive officer to General Fox Conner in the Panama Canal Zone, where he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including Karl von Clausewitz's On War), and later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking. In 1925–26, he attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[24] There he graduated first in a class of 245 officers.[25] He then served as a battalion commander at Fort Benning, Georgia until 1927.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s Eisenhower's career in the peacetime Army stagnated; many of his friends resigned for high-paying business jobs. He was assigned to the American Battle Monuments Commission, directed by General John J. Pershing, then to the Army War College, and then served as executive officer to General George V. Mosely, Assistant Secretary of War, from 1929 to 1933. He then served as chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur, Army Chief of Staff, until 1935, when he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he served as assistant military adviser to the Philippine government. Eisenhower had strong philosophical disagreements with his patron regarding the role of the Philippine army and the leadership qualities that an American army officer should exhibit and develop in his subordinates. The dispute and resulting antipathy lasted the rest of their lives.[26] It is sometimes said that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the challenging personalities of Winston Churchill, George S. Patton and Bernard Law Montgomery during World War II. Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of permanent lieutenant colonel in 1936 after 16 years as a major. He also learned to fly, although he was never rated as a military pilot. He made a solo flight over the Philippines in 1937.

Eisenhower returned to the U.S. in 1939 and held a series of staff positions in Washington, D.C., California and Texas. In June 1941, he was appointed Chief of Staff to General Walter Krueger, Commander of the 3rd Army, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. He was promoted to brigadier general on October 3, 1941.[27] Although his administrative abilities had been noticed, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II he had never held an active command above a battalion and was far from being considered as a potential commander of major operations.

World War II

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in Washington, where he served until June 1942 with responsibility for creating the major war plans to defeat Japan and Germany. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division (WPD), General Leonard T. Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Then he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of the new Operations Division (which replaced WPD) under Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who spotted talent and promoted accordingly.[28]

At the end of May 1942, Eisenhower accompanied Lt. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, commanding general of the Army Air Forces, to London to assess the effectiveness of the then-theater commander in England, Maj. Gen. James E. Chaney. He returned to Washington on June 3 with a pessimistic assessment, stating he had an "uneasy feeling" about Chaney and his staff. On June 23, 1942, he returned to London as Commanding General, European Theater of Operations (ETOUSA), based in London,[29] and replaced Chaney.[30]

In November, he was also appointed Supreme Commander Allied (Expeditionary) Force of the North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA) through the new operational Headquarters A(E)FHQ. The word "expeditionary" was dropped soon after his appointment for security reasons. In February 1943, his authority was extended as commander of AFHQ across the Mediterranean basin to include the British 8th Army, commanded by General Bernard Law Montgomery. The 8th Army had advanced across the Western Desert from the east and was ready for the start of the Tunisia Campaign. Eisenhower gained his fourth star and gave up command of ETOUSA to be commander of NATOUSA. After the capitulation of Axis forces in North Africa, Eisenhower oversaw the invasion of Sicily and the invasion of the Italian mainland.

In December 1943, Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower—not Marshall—would be Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. In January 1944, he resumed command of ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), serving in a dual role until the end of hostilities in Europe in May 1945. In these positions he was charged with planning and carrying out the Allied assault on the coast of Normandy in June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord, the liberation of western Europe and the invasion of Germany. A month after the Normandy D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, the invasion of southern France took place, and control of the forces which took part in the southern invasion passed from the AFHQ to the SHAEF. From then until the end of the War in Europe on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower through SHAEF had supreme command of all operational Allied forces2, and through his command of ETOUSA, administrative command of all U.S. forces, on the Western Front north of the Alps. As recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to General of the Army, equivalent to the rank of Field Marshal in most European armies. In this and the previous high commands he held, Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders. He dealt skillfully with difficult subordinates such as Patton, and allies such as Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle. He had fundamental disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He negotiated with Soviet Marshal Zhukov,[31] and such was the confidence that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had in him, he sometimes worked directly with Stalin, much to the chagrin of the British High Command who disliked being bypassed.

It was never certain that Operation Overlord would succeed. The seriousness surrounding the entire decision, including the timing and the location of the Normandy invasion, might be summarized by a second shorter speech that Eisenhower wrote in advance, in case he needed it. Long after the successful landings on D-Day and the BBC broadcast of Eisenhower's brief speech concerning them, the never-used second speech was found in a shirt pocket by an aide. It read:[32]

- Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.

Aftermath of World War II

Military Governor and Chief of Staff

Following the German unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower was appointed Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, based in Frankfurt am Main. He had no responsibility for the other three zones, controlled by Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Upon discovery of the Nazi concentration camps, he ordered camera crews to comprehensively document evidence of the atrocities in them for use in the Nuremberg Trials. He made the decision to reclassify German prisoners of war (POWs) in U.S. custody as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs). For the treatment of German economy and German civilians Eisenhower followed the orders laid down by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in directive JCS 1067, but softened them by bringing in 400,000 tons of food for civilians and allowing more fraternization.[33][34][35] In dealing with the devastation of postwar Germany he dealt with severe food shortages and a huge influx of refugees by distributing American food and medical supplies.[36] His actions reflected the shifting American attitudes from seeing the German people as villains to seeing them as victims of the Nazis, while aggressively purging ex-Nazis.[37][38]

In November 1945, Eisenhower returned to Washington to replace Marshall as Chief of Staff of the Army. His main role was rapid demobilization of millions of soldiers, a slow job that was delayed by lack of shipping. As East-West tensions over Germany and Greece escalated, Eisenhower was strongly convinced in 1946 that Russia did not want war and that friendly relations could be maintained; he strongly supported the new United Nations. However, in formulating policies regarding the atomic bomb as well as toward the Soviets Truman listened to the State Department and ignored Eisenhower and the entire Pentagon. By mid-1947 Eisenhower was moving toward a containment policy to stop Soviet expansion.[39]

President at Columbia University and NATO Supreme Commander

In 1948, Eisenhower became President of Columbia University, a premier private university in New York. The assignment was described as not being a good fit in either direction.[40] During that year Eisenhower's memoir, Crusade in Europe, was published.[41] Critics regarded it as one of the finest U.S. military memoirs, and it was a major financial success as well.

Eisenhower's stint as president of Columbia University was punctuated by his activity within the Council on Foreign Relations, a study group he led as president concerning the political and military implications of the Marshall Plan, and The American Assembly, Eisenhower's "vision of a great cultural center where business, professional and governmental leaders could meet from time to time to discuss and reach conclusions concerning problems of a social and political nature". Biographer Blanche Weisen Cook suggests that this period served as "the political education of General Eisenhower", as he had to prioritize wide ranging educational, administrative, and financial demands for the university. Through his involvement in the Council on Foreign Relations, he also gained exposure to economic analysis which would become the bedrock of his understanding in economic policy. "Whatever General Eisenhower knows about economics he has learned at the study group meetings" one Aid to Europe member claimed.

One reason for Eisenhower's acceptance of the presidency of the university was to expand his ability to promote "the American form of democracy" through education. He was clear on this point to the trustees involved in the search committee. He informed them that his main purpose was "to promote the basic concepts of education in a democracy." As a result he was "almost incessantly" devoted to the idea of the American Assembly, a concept which he developed into an institution by the end of 1950.

Within months of beginning his tenure as university president, Eisenhower was requested to advise Secretary of Defense James Forrestal on unification of the armed services. Approximately six months after his installation, he became the informal chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon. Two months later he fell ill and spent over a month in recovery at Augusta National Golf Club. He returned to his post in mid-May and in July 1949 took a two-month vacation out of state. Because the American Assembly had begun to take shape, he traveled around the country in mid to late 1950 building financial support from Columbia Associates, an alumni association. Eisenhower was unknowingly building resentment and a reputation among the Columbia faculty and staff as an absentee president who was using the university for his own interests. However, the Columbia trustees refused to accept his resignation in December 1950, when he took leave from the university to become the Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and was given operational command of NATO forces in Europe. Eisenhower retired from active service on May 31, 1952, and resumed the university presidency, which he held until January 1953.

The contacts gained through university and American Assembly fund-raising activities would later become important supporters in Eisenhower's bid for the Republican party nomination and the presidency. Meanwhile, Columbia University's liberal faculty members became disenchanted with the university president's ties to oilmen and businessmen including Leonard McCollum, president of Continental Oil, Frank Abrams, chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey, Bob Kleberg, president of King Ranch, H.J. Porter, a Texas oil producer, Bob Woodruff, president of Coca-Cola and Clarence Francis, General Foods chairman.

As president of Columbia University, Eisenhower gave voice and form to his ingrained opinions about the supremacy and difficulties of American democracy. His tenure marked his transformation from military to civilian leadership. It also enabled him to demonstrate his profound commitment to democratic citizenship. Biographer Travis Beal Jacobs also suggests that the alienation of the Columbia faculty contributed to sharp intellectual criticism of him for many years. [42]

Entry into politics

Not long after his return in 1952, a "Draft Eisenhower" movement in the Republican party persuaded him to declare his candidacy in the 1952 presidential election to counter the candidacy of non-interventionist Senator Robert Taft. (Eisenhower had been courted by both parties in 1948 and had declined to run then.) Eisenhower defeated Taft for the nomination, having won critical delegate votes from Texas, but came to an agreement that Taft would stay out of foreign affairs as Eisenhower followed a conservative domestic policy. Eisenhower's campaign was noted for the simple but effective slogan, "I Like Ike", and was a crusade against the Truman administration's policies regarding "Korea, Communism and Corruption."[43]

Eisenhower promised during his campaign to go to Korea himself and end the war there. He also promised to maintain both a strong NATO commitment against Communism and a corruption-free frugal administration at home. He and his running mate Richard Nixon, whose daughter later married Eisenhower's grandson David, defeated Democrats Adlai Stevenson and John Sparkman in a landslide, marking the first Republican return to the White House in 20 years,[43] with Eisenhower becoming the last President born in the 19th century. Eisenhower, at 62, was the oldest man to be elected President since James Buchanan in 1856.[44] Eisenhower was the only general to serve as President in the 20th century, and the most recent President to have never held elected office prior to the Presidency. The other Presidents not to have sought prior elected office were Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, William Howard Taft, and Herbert Hoover.

Presidency 1953–1961

Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower preached a doctrine of dynamic conservatism.[45] He continued all the major New Deal programs still in operation, especially Social Security. He expanded its programs and rolled them into a new cabinet-level agency, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, while extending benefits to an additional ten million workers. His cabinet, consisting of several corporate executives and one labor leader, was dubbed by one journalist, "Eight millionaires and a plumber."[46]

In 1956, Eisenhower faced Adlai Stevenson and Estes Kefauver on the Democratic ticket. Eisenhower won his second term with 457 of 531 votes in the Electoral College, and 57.6% of the popular vote.

Interstate Highway System

One of Eisenhower's enduring achievements was championing and signing the bill that authorized the Interstate Highway System in 1956.[47] He justified the project through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 as essential to American security during the Cold War. It was believed that large cities would be targets in a possible future war, and the highways were designed to evacuate them and allow the military to move in.

Eisenhower's goal to create improved highways was influenced by his involvement in the U.S. Army's 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy. He was assigned as an observer for the mission, which involved sending a convoy of U.S. Army vehicles coast to coast.[48][49] His subsequent experience with German autobahns during World War II convinced him of the benefits of an Interstate Highway System. Noticing the improved ability to move logistics throughout the country, he thought an Interstate Highway System in the U.S. would not only be beneficial for military operations, but be the building block for continued economic growth.[50]

Foreign policy

Eisenhower's foreign policy was marked by "the brave new world of CIA-led coups and assassinations. It was Eisenhower whose CIA deposed the leaders of Iran, Guatemala, and possibly the Belgian Congo. The Eisenhower administration also planned the Bay of Pigs invasion to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba, which John F. Kennedy was left to carry out."[51] However, he held out an olive branch to the Soviet Union after Joseph Stalin's death.[52]

Mideast and Eisenhower doctrine

Soon after taking office, the Eisenhower administration, in cooperation with the British government, authorized the Central Intelligence Agency to help the Iranian army overthrow Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, and restore the Shah to power.[53]

In November 1956 Eisenhower decided that he could not support the combined British, French and Israeli invasion of Egypt in response to the Suez Crisis, while at the same time condemn the brutal Soviet invasion of Hungary in response to the Hungarian Revolution. Therefore he publicly disavowed his allies at the United Nations, and forced them to withdraw from Egypt.[54] However he later privately acknowledged this as his biggest foreign policy mistake, since he felt it weakened two crucial European Cold War allies, and established Gamel Abdel Nasser as an anti-Western leader who could dominate the Arab world.[55] After the Suez Crisis the United States became the protector of unstable friendly governments in the Middle East via the "Eisenhower Doctrine". Designed by Secretary of State Dulles, it held the U.S. would be "prepared to use armed force...[to counter] aggression from any country controlled by international communism." Further, the United States would provide economic and military aid and, if necessary, use military force to stop the spread of communism in the Middle East.[56]

Eisenhower applied the doctrine in 1957–58 by dispensing economic aid to shore up the Kingdom of Jordan, and by encouraging Syria's neighbors not to consider military operations against it. More dramatically, in July 1958, he sent 15,000 Marines and soldiers to Lebanon as part of Operation Blue Bat, a non-combat peace-keeping mission to stabilize the pro-Western government and to prevent a radical revolution from sweeping over that country. The mission proved a success and the Marines departed three months later. The deployment came in response to the urgent request of Lebanese president Camille Chamoun after sectarian violence had erupted in the country. Washington considered the military intervention successful since it brought about regional stability, weakened Soviet influence, and intimidated the Egyptian and Syrian governments, whose anti-West political position had hardened after the Suez Crisis.[57]

Most Arab countries were skeptical about the "Eisenhower doctrine" because they considered "Zionist imperialism" the real danger. They did, however, take the opportunity to take free money and weapons. Egypt and Syria openly opposed the initiative and were supported by the Soviet Union. However, Egypt received American aid until 1967.[58]

As the Cold War deepened, Dulles sought to isolate the Soviet Union by building regional alliances of nations against it. Critics sometimes called it "pacto-mania".[59]

Vietnam

The French asked Eisenhower for help in French Indochina against the Communists, supplied from China, who were fighting the First Indochina War. In 1953, Eisenhower sent Lt. General John W. "Iron Mike" O'Daniel to Vietnam to study and "assess" the French forces therein.[60] Chief of Staff Matthew Ridgway dissuaded the President from intervening by presenting a comprehensive estimate of the massive military deployment that would be necessary. However, later in 1954, Eisenhower did offer military and economic aid to the new nation of South Vietnam.[61] In the years that followed, Eisenhower increased the number of US military advisors in South Vietnam to 900 men.[62] This due to North Vietnam's support of "uprisings" in the south and concern the nation would fall.[61] After the election of November 1960, Eisenhower in briefing with John F. Kennedy pointed out the communist threat in Southeast Asia as requiring prioritization in the next administration. Eisenhower told Kennedy he considered Laos to be "the cork in the bottle" in regards to the regional threat.[63]

Racial issues

The Eisenhower administration declared racial discrimination a national security issue, meaning that the Communists around the world were using racial discrimination in the U.S. as a point of propaganda attack.[64] The day after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Brown v. Board of Education in which segregated ("separate but equal") schools were ruled to be unconstitutional, Eisenhower told District of Columbia officials to make Washington a model for the rest of the country in integrating black and white public school children.[65][66] He proposed to Congress the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 and signed those acts into law. The 1957 Act for the first time established a permanent civil rights office inside the Justice Department. Although both Acts were weaker than subsequent civil rights legislation, they constituted the first significant civil rights acts since the Civil Rights Act of 1875, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant.

The "Little Rock Nine" incident of 1957 involved the refusal by Arkansas to honor a Federal court order to integrate the schools. Under Executive Order 10730, Eisenhower placed the Arkansas National Guard under Federal control and sent Army troops to escort nine black students into Little Rock Central High School, an all-white public school. The integration did not occur without violence. Eisenhower and Arkansas governor Orval Faubus engaged in tense arguments.

Relations with Congress

Eisenhower had a Republican Congress only for his first two years in office; thereafter, he was compelled to consult closely with Democratic Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson in the Senate and Speaker Sam Rayburn in the House, both of Texas. Joe Martin, the Republican Speaker from 1947–1949 and again from 1953–1955, wrote that Eisenhower "never surrounded himself with assistants who could solve political problems with professional skill. There were exceptions, like . . . Leonard W. Hall, who as chairman of the Republican National Committee, tried to open the administration's eyes to the political facts of life, with occasional success. But these exceptions were not enough to right the balance."[67]

Martin concluded that Eisenhower worked through subordinates in dealing with Congress, with results, "often the reverse of what he has desired. Men and women in Congress arrived there by their own wits and exertions, and they know they have got to be reelected on their own. They are incllined to resent having some young fellow who was picked up by the White House without ever having been elected to office himself coming around and telling them 'The Chief wants this.'. . . The administration never made use of many Republicans of consequcnee whose services in one form or another would have been available for the asking. . . . "[67]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

Eisenhower appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Earl Warren, 1953 (Chief Justice)

- John Marshall Harlan II, 1954

- William J. Brennan, 1956

- Charles Evans Whittaker, 1957

- Potter Stewart, 1958

Other courts

In addition to his five Supreme Court appointments, Eisenhower appointed 45 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 129 judges to the United States district courts.

States admitted to the Union

Health issues

Eisenhower was a chain smoker until March 1949.[68] He was probably the first president to allow his personal health problems to become public while in office.[69] On September 24, 1955, while vacationing in Colorado, he had a serious heart attack that required several weeks' hospitalization. He was treated by Dr. Paul Dudley White, a cardiologist with a national reputation, who regularly informed the press of the president's progress. As a consequence of his heart attack, Eisenhower developed a left ventricular aneurysm, which was in turn the cause of a mild stroke on November 25, 1957. The president also suffered from Crohn's disease, a chronic inflammatory condition of the intestine, which necessitated surgery for a bowel obstruction in June 1956. The last three years of Eisenhower's term in office were ones of relatively good health. Eventually, however, after leaving the White House, he suffered several additional heart attacks and was ultimately impaired physically because of them.[70]

End of presidency 1960-1961

In 1961, Eisenhower became the first U.S. president to be constitutionally prevented from running for re-election to the office, having served the maximum two terms allowed by the 22nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment was ratified in 1951, during Harry S. Truman's term, but it stipulated that Truman would not be affected by the amendment.

Eisenhower was also the first outgoing President to come under the protection of the Former Presidents Act; two then-living former Presidents, Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman, left office before the Act was passed. Under the act, Eisenhower was entitled to receive a lifetime pension, state-provided staff and a Secret Service detail.[71]

In the 1960 election to choose his successor, Eisenhower endorsed his own Vice-President, Republican Richard Nixon against Democrat John F. Kennedy. He thoroughly supported Nixon over Kennedy, telling friends: "I will do almost anything to avoid turning my chair and country over to Kennedy."[43] However, he only campaigned for Nixon in the campaign's final days and even did Nixon some harm. When asked by reporters at the end of a televised press conference to list one of Nixon's policy ideas he had adopted, he joked, "If you give me a week, I might think of one. I don't remember." Kennedy's campaign used the quote in one of its campaign commercials. Nixon lost narrowly to Kennedy. Eisenhower, who was the oldest president in history at that time (then 70), thus handed power over to the youngest elected president - Kennedy then being aged 43.[43]

On January 17, 1961, Eisenhower gave his final televised Address to the Nation from the Oval Office.[72] In his farewell speech to the nation, Eisenhower raised the issue of the Cold War and role of the U.S. armed forces. He described the Cold War saying: "We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose and insidious in method..." and warned about what he saw as unjustified government spending proposals and continued with a warning that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex." Though he said that "we recognize the imperative need for this development," he cautioned that "the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist... Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together."

Because of legal issues related to holding a military rank while in a civilian office, Eisenhower had resigned his permanent commission as General of the Army before entering the office of President of the United States. Upon completion of his Presidential term, his commission on the retired list was reactivated and Eisenhower again was commissioned a five-star general in the United States Army.[73][74]

Post-presidency

Eisenhower retired to the place where he and Mamie had spent much of their post-war time, a working farm adjacent to the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In 1967, the Eisenhowers donated the farm to the National Park Service and since 1980 it has been open to the public as the Eisenhower National Historic Site.[75] In retirement, he did not completely retreat from political life; he spoke at the 1964 Republican National Convention and appeared with Barry Goldwater in a Republican campaign commercial from Gettysburg.[76]

Death and funeral

Eisenhower died of congestive heart failure on March 28, 1969, at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington D.C. The following day his body was moved to the Washington National Cathedral's Bethlehem Chapel where he lay in repose for 28 hours. On March 30, his body was brought by caisson to the United States Capitol where he lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda. On March 31, Eisenhower's body was returned to the National Cathedral where he was given an Episcopal Church funeral service. That evening, Eisenhower's body was placed onto a train en route to Abilene, Kansas. His body arrived on April 2, and was interred later that day in a small chapel on the grounds of the Eisenhower Presidential Library. Eisenhower is buried alongside his son Doud who died at age 3 in 1921, and his wife, Mamie, who died in 1979.[77]

Richard Nixon, by this time himself President, spoke of Eisenhower's death, "Some men are considered great because they lead great armies or they lead powerful nations. For eight years now, Dwight Eisenhower has neither commanded an army nor led a nation; and yet he remained through his final days the world's most admired and respected man, truly the first citizen of the world."[78]

Legacy

After Eisenhower left office, his reputation declined and he was seen as having been a "do-nothing" President. This was partly because of the contrast between Eisenhower and his young activist successor, John F. Kennedy. Despite his unprecedented use of Army troops to enforce a federal desegregation order at Central High School in Little Rock, Eisenhower was criticized for his reluctance to support the civil rights movement to the degree which other activists wanted. Eisenhower was also criticized for his handling of the 1960 U-2 incident and the international embarrassment,[79][80] the Soviet Union's perceived leadership in the Arms race and the Space race, and his failure to publicly oppose McCarthyism. In particular, Eisenhower was criticized for failing to defend George Marshall from attacks by Joseph McCarthy, though he privately deplored McCarthy's tactics and claims.[81] Such omissions were held against him during the liberal climate of the 1960s and 1970s. Since that time, however, Eisenhower's reputation has risen. In recent surveys of historians, Eisenhower often is ranked in the top 10 among all U.S. Presidents.

Although conservatism was riding on the crest of the wave in the 1950s, and Eisenhower shared the sentiment, his administration played a very modest role in shaping the political landscape. Instead of adhering to the party's right-wing orthodoxy, Eisenhower instead looked to moderation and cooperation as a means of governance.[82] This was evidenced in his goal of slowing the growth of New Deal/Fair Deal-era government programs, but not weakening them or rolling them back entirely.[82] Conservative critics of his administration found that he did not do enough to advance the goals of the right: "Eisenhower's victories were," according to Hans Morgenthau, "but accidents without consequence in the history of the Republican party."[83]

Eisenhower was the first President to hire a White House Chief of Staff or "gatekeeper" – an idea that he borrowed from the United States Army, and that has been copied by every president after Lyndon Johnson. (Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter initially tried to operate without a Chief of Staff but both eventually gave up the effort and hired one.)

Eisenhower founded People to People International in 1956, based on his belief that citizen interaction would promote cultural interaction and world peace. The program includes a student ambassador component which sends American youth on educational trips to other countries.[84]

Eisenhower described his position on space and the need for peace during his General Assembly of the United Nations, New York City, September 22, 1960.

"The emergence of this new world poses a vital issue: will outer space be preserved for peaceful use and developed for the benefit of all mankind? Or will it become another focus for the arms race – and thus an area of dangerous and sterile competition? The choice is urgent. And it is ours to make. The nations of the world have recently united in declaring the continent of Antarctica 'off limits' to military preparations. We could extend this principle to an even more important sphere. National vested interests have not yet been developed in space or in celestial bodies. Barriers to agreement are now lower than they will ever be again."[85]

Eisenhower also warned about the emerging military-industrial complex in his Chance for Peace Speech:

"Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter plane with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. This is, I repeat, the best way of life to be found on the road the world has been taking. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron. ... Is there no other way the world may live?"[86]

Eisenhower was the first president to appear on color television. He was videotaped when he spoke at the dedication of WRC-TV's new studios in Washington, D.C., on May 21, 1958. The tape has been preserved and is believed to be the oldest surviving color videotape.[citation needed]

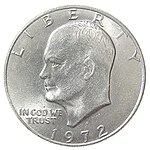

Eisenhower on US currency

Eisenhower's picture was on the dollar coin from 1971 to 1978.[87] Nearly 700 million of the copper-nickel clad coins were minted for general circulation, and nearly 50 million uncirculated and proof issues (in both copper-nickel and 40% silver varieties) were produced for collectors.[88] He reappeared on a commemorative silver dollar issued in 1990, celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth, which with a double image of him showed his two roles, as both a soldier and a statesman.[87] The reverse of the commemorative depicted his home in Gettysburg.[87] As part of the Presidential $1 Coin Program, Eisenhower will be featured on a gold-colored dollar coin in 2015.[89]

Eisenhower on US Postage

Like all presidents before him, Eisenhower was soon to appear on US Postage after his death in 1969. Only seven months later, a commemorative stamp in his honor was first issued on Eisenhower's birthday, October 14, 1969, at the U.S. Post Office in his home town of Abilene, Kansas. Other issues honoring Eisenhower followed in the early 1970s. The last postage stamp (to date) featuring Eisenhower was a commemorative stamp issued in 1990. In all there are six postage stamps issued by the U.S. Post Office in this president's honor.[90] See also:US Presidents on US postage stamps

Tributes and memorials

He is remembered for his role in World War II, the creation of the Interstate Highway System and ending the Korean War. USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, the second Nimitz-class supercarrier, was named in his honor.

The Interstate Highway System is officially known as the 'Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways' in his honor. Commemorative signs reading "Eisenhower Interstate System" and bearing Eisenhower's permanent 5-star rank insignia were introduced in 1993 and are currently displayed throughout the Interstate System. Several highways are also named for him, including the Eisenhower Expressway (Interstate 290) near Chicago and the Eisenhower Tunnel on Interstate 70 west of Denver.

The British A4 class steam locomotive No. 4496 (renumbered 60008) Golden Shuttle was renamed Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1946. It is preserved at the National Railroad Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Eisenhower College was a small, liberal arts college chartered in Seneca Falls, New York in 1965, with classes beginning in 1968. Financial problems forced the school to fall under the management of the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1979. Its last class graduated in 1983.

Eisenhower Hall, the cadet activities building at West Point, was completed in 1974.[92] In 1983, the Eisenhower Monument was unveiled at West Point.

The Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, California was named after the President in 1971.

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center, located at Fort Gordon near Augusta, Georgia, was named in his honor.[93]

In February 1971, Dwight D. Eisenhower School of Freehold Township, New Jersey was officially opened.[94]

In 1983, The Eisenhower Institute was founded in Washington, D.C., as a policy institute to advance Eisenhower's intellectual and leadership legacies.

In 1989, U.S. Ambassador Charles Price and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher dedicated a bronze statue of Eisenhower in Grosvenor Square, London. The statue is located in front of the current US Embassy, London and across from the former command center for the Allied Expeditionary Force during World War II, offices Eisenhower occupied during the war.[95]

In 1999, the United States Congress created the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission, to create an enduring national memorial in Washington, D.C. In 2009, the commission chose the architect Frank Gehry to design the memorial.[96][97] The memorial will stand near the National Mall on Maryland Avenue, SW across the street from the National Air and Space Museum.[98]

On May 7, 2002, the Old Executive Office Building was officially renamed the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. This building is part of the White House Complex, west of the West Wing. It currently houses a number of executive offices, including ones for the Vice President and his or her spouse.[99]

A county park in East Meadow, New York (Long Island) is named in his honor.[100] In addition, Eisenhower State Park on Lake Texoma near his birthplace of Denison is named in his honor; his actual birthplace is currently operated by the State of Texas as Eisenhower Birthplace State Historic Site.

Many public high schools and middle schools in the U.S. are named after Eisenhower.

There is a Mount Eisenhower in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in New Hampshire.

A tree overhanging the 17th hole that always gave him trouble at Augusta National Golf Club, where he was a member, is named the Eisenhower Tree in his honor.

The Eisenhower Golf Club at the United States Air Force Academy, a 36-hole facility featuring the Blue and Silver courses and which is ranked #1 among DoD courses, is named in Eisenhower's honor.

The 18th hole at Cherry Hills Country Club, near Denver, is named in his honor. Eisenhower was a longtime member of the club, one of his favorite courses.[101]

In front of City Hall in Chula Vista, California a tree was dedicated to Eisenhower for the anniversary of his visit to Chula Vista.[102]

Awards and decorations

Other honors

See also

ReferencesSpecific references:

General references:

Further readingMilitary career

Civilian career

Primary sources

External linksAudio and video

For additional research

Organizations |

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

- 1890 births

- 1969 deaths

- American 5 star officers

- American anti-communists

- American military personnel of World War I

- American military personnel of World War II

- American people of Swiss-German descent

- American people of the Korean War

- American people of German descent

- American Presbyterians

- Army Black Knights football players

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in Washington, D.C.

- Cold War leaders

- Companions of the Liberation

- Eisenhower family

- Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur

- Grand Cordons of the Nichan Iftikhar

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Southern Cross

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Vasco Núñez de Balboa

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Honorary Members of the Order of Merit

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

- Knights of the Elephant

- Knights of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri

- World Golf Hall of Fame inductees

- Military-industrial complex

- NATO Supreme Allied Commanders

- Operation Overlord people

- Pennsylvania Republicans

- People from Denison, Texas

- Presidents of Columbia University

- Presidents of the United States

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (Belgium)

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (Luxembourg)

- Recipients of the Cross of Grunwald

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Médaille Militaire

- Recipients of the Ordre de la Libération

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Recipients of the Order of Suvorov

- Recipients of the Order of Victory

- Knights of the Virtuti Militari

- Recipients of the Order of the Cloud and Banner

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin

- Grand Cordons of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion

- Recipients of the Order of Solomon

- Recipients of the Order of George I with Swords

- Recipients of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

- Recipients of the Order of the Aztec Eagle

- Recipients of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite

- Recipients of the Nishan-e-Pakistan

- Recipients of the Order of Sikatuna

- Recipients of the Order of Military Merit (Brazil)

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Chile)

- Recipients of the Czechoslovak War Cross

- Recipients of the Order of the Queen of Sheba

- Grand Crosses of the Order of George I

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Redeemer

- Order of the Holy Sepulchre

- Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Oak Crown

- Recipients of the Order of Manuel Amador Guerrero

- Republican Party Presidents of the United States

- United States Army Chiefs of Staff

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- United States Army generals

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States military governors

- United States presidential candidates, 1952

- United States presidential candidates, 1956

- United States Army War College alumni

- American military personnel of German descent