Anfield

View from the Kop | |

| |

| Location | Liverpool, Merseyside, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°25′50.95″N 2°57′38.98″W / 53.4308194°N 2.9608278°W |

| Owner | Liverpool F.C.[1] |

| Operator | Liverpool F.C. |

| Capacity | 45,276[3] |

| Field size | 101 metres (110 yd) by 68 metres (74 yd)[3] |

| Surface | Desso GrassMaster[2] |

| Opened | 1884 |

| Tenants | |

| 1884–1892 1892–present | |

Anfield is an association football stadium in the district of Anfield, Liverpool, England, with a seating capacity of 45,276. It has been the home of Liverpool F.C. since their formation in 1892 and was originally the home of Everton F.C. from 1884 to 1892, before they moved to Goodison Park. Used as a venue during Euro 96, the ground has also hosted numerous England internationals at senior level, and is scheduled to host matches during the 2015 Rugby World Cup.

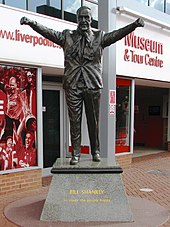

Over the course of its history the stadium has gone through various stages of renovation and development, resulting in the current configuration of four stands: the Spion Kop, Main Stand, Centenary Stand, and Anfield Road. The record attendance at the stadium is 61,905, which was set in a match between Liverpool and Wolverhampton Wanderers in 1952. This record was set before the ground's conversion to an all-seater stadium in 1994; the changes, a result of the Taylor Report, include greatly reduced capacity. Notable features of the stadium include two gates named after former Liverpool managers: Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley. A statue of Shankly is situated outside the stadium. Anfield's public transport links include rail and bus services, but it lacks dedicated parking facilities. The ground is 2 miles (3 km) from Lime Street Station.

Plans to replace Anfield with a new 60,000-capacity stadium in adjacent Stanley Park were initiated in 2002, with a provisional opening date of August 2005. Subsequent problems with securing funding for the project, and the state of the financial market since 2008, make it certain as of 2011 that football will continue to be played at Anfield for at least a few more years. Fenway Sports Group's acquisition of Liverpool in 2010 has made the construction of a new stadium doubtful, as they have hinted at a preference to redevelop Anfield.

History

Opened in 1884, Anfield was originally owned by John Orrell, a minor land owner who was a friend of an Everton F.C. member John Houlding.[4] Everton, who previously played at Priory Road, were in need of a new venue owing to the noise produced by the crowd on match days.[5] Orrell lent the pitch to the club in exchange for a small rent. The first match at the ground was between Everton and Earlestown on 28 September 1884, which Everton won 5–0.[6] During Everton's tenure at the stadium, stands were erected for some of the 8,000-plus spectators regularly attending matches, although the ground was capable of holding around 20,000 spectators and occasionally did. The ground was considered of international standard at the time, playing host to the British Home Championship match between England and Ireland in 1889. Anfield's first league match was played on 8 September 1888, between Everton and Accrington F.C. Everton quickly improved as a team, and became Anfield's first league champions in the 1890–91 season.[7]

In 1892, negotiations to purchase the land at Anfield from Orrell escalated into a dispute between Houlding and the Everton F.C. committee over how the club was run. Events culminated in Everton's move to Goodison Park.[5] Houlding was left with an empty stadium, and decided to form a new club to occupy it. The new team was called Liverpool F.C. and Athletic Grounds Ltd, and the club's first match at Anfield was a friendly played in front of 200 people on 1 September 1892, against Rotherham Town. Liverpool won 7–1.[8]

Liverpool's first Football League match at Anfield was played on 9 September 1893, against Lincoln City. Liverpool won 4–0 in front of 5,000 spectators.[9] A new stand capable of holding 3,000 spectators was constructed in 1895 on the site of the present Main Stand. Designed by architect Archibald Leitch,[10] the stand had a distinctive red and white gable, and was similar to the main stand at Newcastle United's ground St James' Park.[8] Another stand was constructed at the Anfield Road end in 1903, built from timber and corrugated iron. After Liverpool had won their second League championship in 1906, a new stand was built along the Walton Breck Road. Local journalist Ernest Edwards, who was the sports editor of newspapers the Liverpool Daily Post and Echo, christened it the Spion Kop; it was named after a famous hill in South Africa where a local regiment had suffered heavy losses during the Boer War in 1900. More than 300 men had died, many of them from Liverpool, as the British army attempted to capture the strategic hilltop. Around the same period a stand was also built along Kemlyn Road.[11]

The ground remained much the same until 1928, when the Kop was redesigned and extended to hold 30,000 spectators, all standing. A roof was erected as well.[12] Many stadia in England had stands named after the Spion Kop. Anfield's was the largest Kop in the country at the time—it was able to hold more supporters than some entire football grounds.[13] In the same year the topmast of the SS Great Eastern, one of the first iron ships, was rescued from the ship breaking yard at nearby Rock Ferry, and was hauled up Everton Valley by a team of horses, to be erected alongside the new Kop. It still stands there, serving as a flag pole.[14]

Floodlights were installed at a cost of £12,000 in 1957. On 30 October they were switched on for the first time for a match against Everton to commemorate the 75-year anniversary of the Liverpool County Football Association.[13] In 1963 the old Kemlyn Road stand was replaced by a cantilevered stand, built at a cost of £350,000, and able to hold 6,700 spectators.[15] Two years later alterations were made at the Anfield Road end, turning it into a large covered standing area. The biggest redevelopment came in 1973, when the old Main Stand was demolished and a new one constructed. At the same time, the pylon floodlights were pulled down and new lights installed along the top of the Kemlyn Road and Main Stands. The new stand was officially opened by the Duke of Kent on 10 March 1973.[15] In the 1980s the paddock in front of the Main Stand was turned into seating, and in 1982 seats were introduced at the Anfield Road end. The Shankly Gates were erected in 1982, a tribute to former manager Bill Shankly; his widow Nessie unlocked them for the first time on 26 August 1982.[14] Across the Shankly Gates are the words You'll Never Walk Alone, the title of the hit song by Gerry & The Pacemakers adopted by Liverpool fans as the club's anthem during Shankly's time as manager.[16]

Coloured seats and a police room were added to the Kemlyn Road stand in 1987. After the Hillsborough disaster in 1989 where overcrowding led to the deaths of 96 Liverpool fans, the Taylor Report recommended that all grounds in the country should be converted into all-seater grounds by May 1994.[17] A second tier was added to the Kemlyn Road stand in 1992, turning it into a double-decker layout. It included executive boxes and function suites as well as 11,000 seating spaces. Plans to expand the stand had been made earlier, with the club buying up houses on Kemlyn Road during the 1970s and 1980s, but had to be put on hold until 1990 because two sisters, Joan and Nora Mason, refused to sell their house. When the club reached an agreement with the sisters in 1990, the expansion plans were put into action.[18] The stand—re-named the Centenary Stand—was officially opened on 1 September 1992 by UEFA president Lennart Johansson. The Kop was rebuilt in 1994 after the recommendations of the Taylor Report and became all seated; it is still a single tier, and the capacity was significantly reduced to 12,390.[13]

On 4 December 1997, a bronze statue of Bill Shankly was unveiled at the visitors' centre in front of the Kop. Standing at over 8 feet (2.4 m) tall, the statue depicts Shankly with a fan's scarf around his neck, in a familiar pose he adopted when receiving applause from fans. Inscribed on the statue are the words "Bill Shankly – He Made the People Happy".[19] The Hillsborough memorial is situated alongside the Shankly Gates, and is always decorated with flowers and tributes to the 96 people who died in 1989 as a result of the disaster. At the centre of the memorial is an eternal flame, signifying that those who died will never be forgotten.[20] The most recent structural change to Anfield came in 1998 when the new two-tier Anfield Road end was opened. The stand has encountered a number of problems since its redevelopment; at the beginning of the 1999–2000 season, a series of support poles and stanchions had to be brought in to give extra stability to the top tier of the stand. During Ronnie Moran's testimonial match against Celtic, many fans complained of movement of the top tier. At the same time that the stanchions were inserted, the executive seating area was expanded by two rows in the main stand, lowering the seating capacity in the paddock.[21]

Structures and facilities

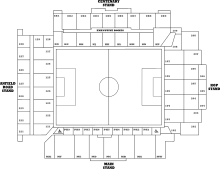

Anfield comprises 45,276 seats split between four stands: the Anfield Road end, the Centenary Stand, the Kop, and the Main Stand. The Anfield Road end and Centenary Stand are two-tiered, while the Kop and Main Stand are single-tiered.[22] Entry to the stadium is gained by radio-frequency identification (RFID) smart cards rather than the traditional manned turnstile. This system, used in all 80 turnstiles around Anfield, was introduced in 2005.[23]

The Kop is a large single-tiered stand. Originally a large terraced banking providing accommodation for more than 30,000 spectators, the current incarnation was constructed in 1994–95 and is single-tiered with no executive boxes. The Kop houses the club's museum, the Reducate centre and the official club shop.[24] The Kop is the most-renowned stand at Anfield among home and away supporters, with the people who occupy the stand referred to as kopites. Such was the reputation that the stand had it was claimed that the crowd in the Kop could suck the ball into the goal.[25] Traditionally, Liverpool's most vocal supporters congregate in this stand.[26]

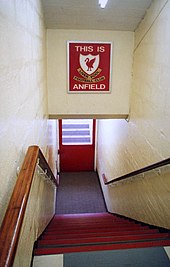

The oldest stand at Anfield is the Main Stand, which was completed in 1982. It is a single-tiered stand that houses the dressing rooms and directors' box. The press and directors VIP box are located in the middle of the stand. The large roof is supported by two thin central uprights, with a large suspended television camera gantry.[27] The players' tunnel and the technical area where the managers and substitutes sit during the match are in the middle of the stand at pitch level. Above the stairs leading down to the pitch hangs a sign stating "THIS IS ANFIELD". Its purpose is to both intimidate the opposition and to bring the Liverpool players who touch it good luck. Accordingly, Liverpool players and coaching staff reach up and place one or both hands on it as they pass underneath.[28]

The Centenary Stand is a two-tiered stand. Originally a single-tiered stand called the Kemlyn Road Stand, the second tier was added in 1992 to coincide with the club's centenary.[29] It is located opposite of the Main Stand and houses directors' boxes, which are between the two tiers. The stand also houses the ground's police station.[22]

The Anfield Road stand, on the left side of the Main Stand, houses the away fans during matches. The Anfield Road End was rebuilt in 1965, and multi-coloured seats were added in 1982. Originally a single-tier stand, a further revamp, which was completed in 1998, gave the stand a second-tier providing additional seating.[29]

There are 59 spaces available in the stadium to accommodate wheelchair users who have season tickets; a further 33 spaces are available for general sale and 8 are allocated to away supporters. These spaces are located in the Main Stand, Anfield Road Stand and The Kop. There are 38 spaces available for the visually impaired, which are situated in the paddock area of the Main Stand, with space for one personal assistant each. A headset with full commentary is provided.[30]

The stadium features tributes to two of the club's most successful managers. The Paisley Gateway is a tribute to Bob Paisley, who guided Liverpool to three European Cups and six League Championships in the 1970s and '80s. The gates were erected at the Kop; their design includes representations of the three European Cups Paisley won during his tenure, the crest of his birthplace in Hetton-le-Hole, and the crest of Liverpool F.C.[31] The Shankly Gates, in tribute of Bill Shankly, Paisley's predecessor between 1959 and 1974, are at the Anfield Road end. Their design includes a Scottish flag, a Scottish thistle, the Liverpool badge, and the words "You'll Never Walk Alone".[32]

Future

Plans to replace Anfield were originally initiated by Liverpool in May 2002.[33] The proposed capacity was 55,000, but it was later revised to 61,000, with 1,000 seats given for segregation between home and away fans. Several attempts were made between 2003 to 2007 by the Liverpool City Council to instigate a groundshare of the proposed stadium with local rivals Everton, but this move was rejected, as neither club favoured it.[34] On 30 July 2004 Liverpool was granted planning permission to build a new stadium 300 yards (270 m) away from Anfield at Stanley Park.[35] On 8 September 2006 Liverpool City Council agreed to grant Liverpool F.C. a 999-year lease of the land on the proposed site.[36]

Following the takeover of Liverpool F.C. on 6 February 2007 by George Gillett and Tom Hicks, the proposed stadium was redesigned to reduce the costs of construction. In November 2007 the redesigned layout was approved by the council, and construction was due to start in early 2008.[37] The new stadium, provisionally called Stanley Park Stadium, was to be built by HKS, Inc.. It was scheduled to open in August 2011 with a capacity of 71,000.[38] If the new stadium is built Anfield will be demolished. The land will become home to the centrepiece for the Anfield Plaza development, which would include a hotel, restaurants, and offices.[39] However, the construction of Stanley Park was delayed following the economic crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recession, which directly affected the then American owners. The situation was worsened because the club was bought with borrowed money, not the owners' capital, and interest rates were higher than expected.[40] Hicks and Gillett promised to begin work on the stadium within 60 days of acquisition of the club, but had trouble financing the estimated £300 million needed for the Stanley Park development. The deadline passed, and as of June 2011 the site remains untouched.[41] The delays had repercussions in the local district of Anfield, with regeneration plans on hold until the future of the football stadium is decided.[42]

The acquisition of Liverpool by Fenway Sports Group in October 2010 put into question whether Liverpool would leave Anfield. In February 2011 the new club owner, John W. Henry, stated he had a preference for remaining at Anfield and expanding the capacity. After attending a number of games at Anfield, Henry stated that "the Kop is unrivalled", adding "it would be hard to replicate that feeling anywhere else".[43]

Other uses

Anfield has hosted numerous international matches, and was one of the venues used during Euro 96; the ground hosted three group games and a quarter-final.[44] The first international match hosted at Anfield was between England and Ireland, in 1889. England won the match 6–1. Anfield was also the home venue for several of England's international football matches in the early 1900s and for the Welsh team in the later part of that century.[45][46] Anfield has also played host to five FA Cup semi-finals, the last of which was in 1929.[45] The most recent international to be hosted at Anfield was England's 2–1 victory over Uruguay on 1 March 2006.[47] England has played two testimonial matches against Liverpool at Anfield. The first was in 1983, when England faced Liverpool for Phil Thompson's testimonial. Then, in 1988, England visited again for Alan Hansen's testimonial.[48]

Anfield has been the venue for many other events. During the mid-twenties, Anfield was the finishing line for the city marathon. Liverpool held an annual race which started from St George's plateau in the city centre and finished with a lap of Anfield.[45] Boxing matches were regularly held at Anfield during the inter-war years, including a number of British boxing championships; on 12 June 1934 Nel Tarleton beat Freddie Miller for the World Featherweight title. Professional tennis was played at Anfield on boards on the pitch. US Open champion, Bill Tilden, and Wimbledon champion, Fred Perry, entertained the crowds in an exhibition match. In 1958, an exhibition basketball match featuring the Harlem Globetrotters was held at the ground.[49] The 1991 World Club Challenge rugby league match, between the Penrith Panthers, winners of the Australian National Rugby League, and the Wigan Warriors, winners of the European Super League was held at the ground in front of 20,152 people. In addition to rugby league, Anfield has been confirmed as one of the grounds that will host matches during the 2015 Rugby Union World Cup.[50] Aside from sporting uses, Anfield has been a venue for musicians of different genres as well as evangelical preachers. One week in July 1984, the American evangelist Billy Graham preached at Anfield, attracting crowds of over 30,000 each night.[45] Anfield was featured in Liverpool's 2008 European Capital of Culture celebrations: 36,000 people attended a concert on 1 June 2008, featuring The Zutons, Kaiser Chiefs, and Paul McCartney.[51]

Records

The highest attendance recorded at Anfield is 61,905, for Liverpool's match against Wolverhampton Wanderers in the FA Cup fifth round, on 2 February 1952.[52] The record modern (all-seated) attendance is 44,983, for a match against Tottenham Hotspur on 14 January 2006.[53] The lowest attendance recorded at Anfield was 1,000 for a match against Loughborough on 7 December 1895.[54]

Liverpool did not lose a match at Anfield during the 1893–94, 1970–71, 1976–77, 1978–79, 1979–80, 1987–88, and 2008–09 seasons. They won all their home games during the 1893–94 season. Liverpool's longest winning streak at home extended from January 1978 to January 1981, a period encompassing 85 games, in which Liverpool scored 212 goals and conceded 35.[52] Liverpool's worst losing streak at Anfield is three games. This occurred three times in the club's history to date (1899–1900, 1906–07 and 1908–09 seasons).[55]

Transport

The stadium is about 2 miles (3 km) from Lime Street Station,[56] which lies on a branch of the West Coast Main Line from London Euston. Kirkdale Station, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the stadium, is the nearest station to Anfield. Fans travelling by train for matches may book direct to Anfield or Goodison Park, changing to the Merseytravel Soccerbus service at Sandhills Station on the Merseyrail Northern Line.[57] The stadium has no parking facilities for supporters, and the streets around the ground allow parking only for residents with permits. There are proposals under consideration for reinstating passenger traffic on the Bootle Branch, which would cut the distance from the nearest train station to about 0.5 miles (1 km).[58]

Footnotes

- ^ "Corporate Information". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Football projects". Desso Sports. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ a b Premier League. Premier League Handbook (PDF). The Football Association Premier League Ltd. p. 21. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Kelly (1988). p. 13.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b "LFC Story". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Liversedge (1991). p. 112.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The Everton Story: 1878–1930". Everton F.C. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ a b Kelly (1988). p. 187.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Graham (1984). p. 15.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Whitehead, Richard (18 April 2005). "Man who built his place in history". The Times. London. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Kelly (1988). p. 117.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Liversedge (1991). p. 113.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Pearce, James (23 August 2006). "How Kop tuned in to glory days". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ a b Kelly (1988). p. 117.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Inglis (1983). p. 210.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Smith (2008). pp. 68–69.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Fact-sheet two: Hillsborough and the Taylor Report". Football Industry Group at Liverpool University. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 125.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 103.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Hillsborough". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Liverpool stand strengthened". BBC Sport. 10 August 2000. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Seating Plan". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "A Sporting Chance for RFID" (PDF). Chronos. p. 4. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "Virtual Tour". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ Burt, Jason (16 January 2011). "Liverpool 2 Everton 2: match report". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "Football First 11: Stunning stadiums". CNN. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ^ Inglis (1983). p. 211.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 110.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b "Timeline". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Accessibility". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 88.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 31.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Liverpool unveil new stadium". BBC Sport. 17 May 2002. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool get groundshare request". BBC Sport. 28 March 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Hornby, Mike (31 July 2004). "Reds stadium gets go-ahead". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ "Liverpool get go-ahead on stadium". BBC Sport. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ "New stadium gets the green light". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Liverpool's stadium move granted". BBC. 11 June 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ Hookham, Mike (23 October 2003). "Public park plan for Anfield turf". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- ^ Barrett, Tony (15 May 2008). "Hicks hit by credit crunch". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ Barrett, Tony (8 February 2008). "From Hope to Despair". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy (2 May 2008). "Stanley Park Doubts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Henry hints at revamping Anfield". BBC Sport. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Puric, Bojan (7 December 2001). "Euro 1996". Rec. Sport. Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF). Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Kelly (1988). p. 118.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nygård, Jostein (16 May 2008). "International matches of Wales". Rec. Sport. Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF). Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ "England 2–1 Uruguay". BBC Sport. 1 March 2006. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Moynihan (2008). p. 59.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Inglis (1983). p. 209.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Rugby World Cup: guide to England 2015 stadiums". The Daily Telegraph. 20 July 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Reynolds, Gilian (2 June 2008). "Sir Paul McCartney rocks Anfield stadium". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Anfield". LFC History. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Adams (2007). p. 120.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "LFC Records". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Liverpool's worst losing run – Top 10". LFC History. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Getting to Anfield". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ "Soccerbus". Merseytravel. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ "Opportunities and Challenges" (PDF). Network Rail. p. 11. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

References

- Adams, Duncan (2007). A Fan's Guide to Football Grounds: England and Wales. Hersham: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3268-2.

- Graham, Matthew (1984). Liverpool. Twickenham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0-600-50254-6.

- Inglis, Simon (1983). The Football Grounds of England and Wales. Beverley: Willow. ISBN 0-00-218024-3.

- Kelly, Stephen F. (1988). You'll Never Walk Alone. London: Queen Anne Press. ISBN 0-356-19594-5.

- Liversedge, Stan (1991). Liverpool The Official Centenary History. London: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0-600-57308-7.

- Moynihan, Leo (2008). The Liverpool Miscellany. London: Vision Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90532-646-4.

- Smith, Tommy (2008). Anfield Iron. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 0593059581.

External links