Neisseria meningitidis

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (May 2011) |

| Neisseria meningitidis | |

|---|---|

| |

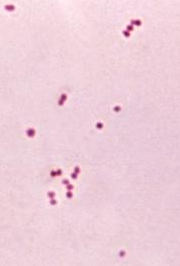

| Photomicrograph of N. meningitidis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. meningitidis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neisseria meningitidis Albrecht & Ghon 1901

| |

Neisseria meningitidis is a bacterium that can cause meningitis[1] and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia. N. meningitidis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality during childhood in industrialized countries and hs been responsible for epidemics in Africa and in Asia.[2]

Approximately 2500 to 3500 cases of N. meningitidis infection occur annually in the United States, with a case rate of about 1 in 100,000. Children younger than 5 years are at greatest risk, followed by teenagers of high school age. Rates in sub-Saharan Africa can be as high as 1 in 1000 to 1 in 100.[3]

Anton Weichselbaum in 1887 first discovered the disease in patients infected with meningococci.[4]

Meningococci only infect humans and have never been isolated from animals because the bacterium cannot get iron other than from human sources (transferrin and lactoferrin).[5]

It exists as normal flora (nonpathogenic) in the nasopharynx of up to 5-15% of adults.[6] It causes the only form of bacterial meningitis known to occur epidemically. Streptococcus pneumoniae (aka) pneumococcus is the most common bacterial etiology of meningitis in children beyond 2 months of age(1-3 per 100,000).

Meningococcus is spread through the exchange of saliva and other respiratory secretions during activities like coughing, kissing, and chewing on toys. Though it initially produces general symptoms like fatigue, it can rapidly progress from fever, headache and neck stiffness to coma and death. The symptoms are easily confused with those of meningitis caused by other organisms such as Hemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae.[3] Death occurs in approximately 10% of cases.[5] Those with impaired immunity may be at particular risk of meningococcus (e.g. those with nephrotic syndrome or splenectomy; vaccines are given in cases of removed or non-functioning spleens).

Suspicion of meningitis is a medical emergency and immediate medical assessment is recommended. Current guidance in the United Kingdom is that if a case of meningococcal meningitis or septicaemia (infection of the blood) is suspected intravenous antibiotics should given and the ill person admitted to the hospital.[7] This means that laboratory tests may be less likely to confirm the presence of Neisseria meningitidis as the antibiotics will dramatically lower the number of bacteria in the body. The UK guidance is based on the idea that the reduced ability to identify the bacteria is outweighed by reduced chance of death.

Septicaemia caused by Neisseria meningitidis has received much less public attention than meningococcal meningitis even though septicaemia has been linked to infant deaths.[8] Meningococcal septicaemia typically causes a purpuric rash that does not lose its color when pressed with a glass ("non-blanching") and does not cause the classical symptoms of meningitis. This means the condition may be ignored by those not aware of the significance of the rash. Septicaemia carries an approximate 50% mortality rate over a few hours from initial onset. Many health organizations advise anyone with a non-blanching rash to go to a hospital as soon as possible.[citation needed] Note that not all cases of a purpura-like rash are due to meningococcal septicaemia; however, other possible causes need prompt investigation as well (e.g. ITP a platelet disorder or Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

Other severe complications include Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (a massive, usually bilateral, hemorrhage into the adrenal glands caused by fulminant meningococcemia), adrenal insufficiency, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[3]

Subtypes

These are classified according to the antigenic structure of their polysaccharide capsule.[citation needed] Of the twelve groups of N. meningitidis have been identified, five of these (A, B, C, W135, and X) are able to cause epidemics.[9]

Virulence

Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is a component of the outer membrane of N. meningitidis which acts as an endotoxin which is responsible for fever, septic shock, and hemorrhage due to the destruction of red blood cells.[10] Other virulence factors include a polysaccharide capsule which prevents host phagocytosis and aids in evasion of the host immune response; and fimbriae which mediate attachment of the bacterium to the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx.[11][12]

Recently a hypervirulent strain was discovered in China. Its impact is yet to be determined.[3]

Mechanisms of cellular invasion

N. meningitidis is an intracellular human-specific pathogen responsible for septicemia and meningitis. Like most bacterial intracellular pathogens, N. meningitidis exploits host cell signaling pathways to promote its uptake by host cells. N.meningitidis does not have a type III secretion system nor a type IV secretion system.[13] The signaling leading to bacterial internalization is induced by the type IV pili, which are the main means of meningococcal adhesion onto host cells. The signaling induced following Type IV pilus-mediated adhesion is responsible for the formation of microvilli-like structures at the site of the bacterial-cell interaction.[11] These microvilli trigger the internalization of the bacteria into host cells. A major consequence of these signaling events is a reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, which leads to the formation of membrane protrusions, engulfing bacterial pathogens into intracellular vacuoles. Efficient internalization of N. meningitidis also requires the activation of an alternative signaling pathway coupled with the activation of the tyrosine kinase receptor ErbB2. Beside Type IV pili, other outer membrane proteins may be involved in other mechanism of bacteria internalization into cells.[14]

Diagnosis

The gold standard of diagnosis is isolation of N. meningitidis from sterile body fluid.[3] A CSF specimen is sent to the laboratory immediately for identification of the organism. Diagnosis relies on culturing the organism on a chocolate agar plate. Further testing to differentiate the species includes testing for oxidase, catalase (all clinically relevant Neisseria show a positive reaction) and the carbohydrates maltose, sucrose, and glucose test in which N. meningitidis will ferment (that is, utilize) the glucose and maltose. Serology determines the subgroup of the organism.

If the bacteria reach the circulation, then blood cultures should be drawn and processed accordingly.

Clinical tests that are used currently for the diagnosis of meningococcal disease take between 2 and 48 hours and often rely on the culturing of bacteria from either blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. However, polymerase chain reaction tests can be used to identify the organism even after antibiotics have begun to reduce the infection. As the disease has a fatality risk approaching 15% within 12 hours of infection, it is crucial to initiate testing as quickly as possible but not to wait for the results before initiating antibiotic therapy.[3]

Treatment

Patients with documented N. meningitidis infection should be hospitalized immediately for treatment with antibiotics. [3] Third-generation cephalosporins (i.e. cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, etc.) should be used to treat a suspected or culture-proven meningococcal infection prior to susceptibility results. Empiric treatment should be sought if an LP cannot be done within 30 minutes of entry to the ED! While antibiotic treatment may affect the outcome of an LP (culture/sensi), a diagnosis may be established on the basis of blood-culture and clinical exam.

Prevention

All recent contacts of the infected patient over the 7 days before onset should receive medication to prevent them from contracting the infection. This especially includes young children and their child caregivers or nursery-school contacts, as well as anyone who had direct exposure to the patient through kissing, sharing utensils, or medical interventions such as mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Anyone who frequently ate, slept or stayed at the patient's home during the 7 days before the onset of symptom, or those who sat beside the patient on an airplane flight of 8 hours or longer, should also receive chemoprophylaxis.[3]

There are currently three vaccines available in the U.S. to prevent meningococcal disease. All three vaccines are effective against the same serogroups: A, C, Y, and W-135. Two meningococcal conjugate vaccines (MCV4) are licensed for use in the U.S. The first conjugate vaccine was licensed in 2005, the second in 2010. Conjugate vaccines are the preferred vaccine for people 2 through 55 years of age. A meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4) has been available since the 1970s and is the only meningococcal vaccine licensed for people older than 55. MPSV4 may be used in people ages 2 - 55 years old if the MCV4 vaccines are not available or contraindicated. Information about who should receive the meningococcal vaccine is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[15]

See also

References

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 329–333. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Genco, C; Wetzler, L (editors) (2010). Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Mola SJ, Nield LS, and Weisse ME (February 27, 2008). "Treatment and Prevention of N. meningitidis Infection". Infections in Medicine.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Deuren, M., Brandtzaeg, P., and van der Meer, J .W. .M. (2000). Update on meningoccal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clinical Microbiological Reviews. 13, 144-166

- ^ a b Meningococcal Disease (2001) Humana Press, Andrew J. Pollard and Martin C.J. Maiden

- ^ "Neisseria meningitidis". Brown University. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ Health Protection Agency Meningococcus Forum (August 2006). Guidance for public health management of meningococcal disease in the UK. Available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1194947389261

- ^ Meningococcal Vaccines (2001) Humana Press, Andrew J. Pollard and Martin C.J. Maiden

- ^ "Meningococcal meningitis". who.int. World Health Organization. 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Lipooligosaccharides: the principal glycolipids of the neisserial outer membrane." Griffiss JM, et al. Rev Infect Dis. 1988 Jul-Aug;10 Suppl 2:S287-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2460911

- ^ a b Jarrell, K (editor) (2009). Pili and Flagella: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-48-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Ullrich, M (editor) (2009). Bacterial Polysaccharides: Current Innovations and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-45-5.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Wooldridge, K (editor) (2009). Bacterial Secreted Proteins: Secretory Mechanisms and Role in Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-42-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Carbonnelle E; et al. (2010). "Mechanisms of Cellular Invasion of Neisseria meningitidis". Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Menningococcal Vaccines - What You Need to Know" (2008). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/vis-mening.pdf