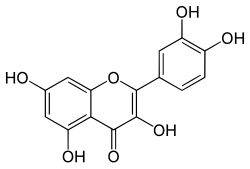

Quercetin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one

| |

| Other names

Sophoretin

Meletin Quercetine Xanthaurine Quercetol Quercitin Quertine Flavin meletin | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.807 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H10O7 | |

| Molar mass | 302.236 g/mol |

| Density | 1.799 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 316 °C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Quercetin /ˈkwɜrsɨtɨn/, a flavonol, is a plant-derived flavonoid found in fruits, vegetables, leaves and grains. It also may be used as an ingredient in supplements, beverages or foods.

Occurrence

Quercetin is a flavonoid widely distributed in nature. The name has been used since 1857, and is derived from quercetum (oak forest), after Quercus.[1][2] It is a naturally-occurring polar auxin transport inhibitor.[3]

Foods rich in quercetin include black and green tea (Camellia sinensis; 2000–2500 mg/kg), capers (1800 mg/kg),[4] lovage (1700 mg/kg), apples (44 mg/kg), onion, especially red onion (1910 mg/kg) (higher concentrations of quercetin occur in the outermost rings[5]), red grapes, citrus fruit, tomato, broccoli and other leafy green vegetables, and a number of berries, including raspberry, bog whortleberry (158 mg/kg, fresh weight), lingonberry (cultivated 74 mg/kg, wild 146 mg/kg), cranberry (cultivated 83 mg/kg, wild 121 mg/kg), chokeberry (89 mg/kg), sweet rowan (85 mg/kg), rowanberry (63 mg/kg), sea buckthorn berry (62 mg/kg), crowberry (cultivated 53 mg/kg, wild 56 mg/kg),[6] and the fruit of the prickly pear cactus. A recent study found that organically grown tomatoes had 79% more quercetin than "conventionally grown".[7]

A study[8] by the University of Queensland, Australia has also indicated the presence of quercetin in varieties of honey, including honey derived from eucalyptus and tea tree flowers.[9]

Biosynthesis

File:Biosynthesis of Quercetin.jpg The biosynthesis of quercetin is summarized in the above figure.[10] Phenylalanine(1) is converted to 4-coumaroyl-CoA(2) in a series of steps known as the general phenylpropanoid pathway using phenyl ammonialyase, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase, and 4-coumaroylCoA-ligase. 4-coumaroyl-CoA(2) is added to three molecules of malonyl-CoA(3) to form tetrahydroxychalcone(4) using 7,2’-dihydroxy, 4’-methoxyisoflavanol synthase. Tetrahydroxychalcone(4) is then converted into naringenin(5) using chalcone isomerase. Naringenin(5) is then converted into eriodictyol(6) using flavanoid 3’ hydroxylase. Eriodictyol(6) is then converted into dihydroquercetin(7) with flavanone 3-hydroxylase, which is then converted into quercetin using flavanol synthase.[11]

Glycosides

Quercetin is the aglycone form of a number of other flavonoid glycosides, such as rutin and quercitrin, found in citrus fruit, buckwheat and onions. Quercetin forms the glycosides quercitrin and rutin together with rhamnose and rutinose, respectively. Likewise guaijaverin is the 3-O-arabinoside, hyperoside is the 3-O-galactoside, isoquercitin is the 3-O-glucoside, and spiraeoside is the 4'-O-glucoside. CTN-986 is a quercetin derivative found in cottonseeds and cottonseed oil.

Effects of consumption by humans and other animals

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

Quercetin itself (aglycone quercetin), as opposed to quercetin glycoconjugates, is not a normal dietary component. In a bioavailability study in rats, radiolabelled quercetin-4'-glucoside was converted to phenolic acids as it passed through the gastrointestinal tract, producing compounds not monitored in several previous animal studies of aglycone quercetin. All but 4% of the radiolabel was recovered within 72 hours, with 69% recovered in urine.[12]

Quercetin has neither been confirmed scientifically as a specific therapeutic for any condition nor been approved by any regulatory agency. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved any health claims for quercetin.[13]

Preliminary research

Antiviral

In a 2007 study that assessed the anti-Hepatitis B effects of Hyperoside, and that was published in the Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, it was shown that Hyperoside (which is the 3-O-galactoside of quercetin) is a strong inhibitor of HBsAg and HBeAg secretion in 2.2.15 cells. [14]

In another study also published in 2007 in the Archives of Pharmacal Research it was shown that quercetin, quercitrin and myricetin 3-O-beta-D-galactopyranoside displayed inhibition against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, all with IC50 values of 60 microM. [15]

Cancer

The American Cancer Society says while quercetin "has been promoted as being effective against a wide variety of diseases, including cancer," and "some early lab results appear promising, as of yet there is no reliable clinical evidence that quercetin can prevent or treat cancer in humans." In the amounts consumed in a healthy diet, quercetin "is unlikely to cause any major problems or benefits."[16]

In laboratory studies of cells in vitro, quercetin produces changes that are also produced by compounds that cause cancer (carcinogens), but these studies do not report increased cancer in animals or humans.[17][18][19]

From laboratory studies is conjecture that quercetin may affect certain mechanisms of cancer.[20][21] An 8-year study found the presence of three flavonols — kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin — in a normal diet was associated with 23% reduced risk of pancreatic cancer, a rare but frequently fatal disease, in tobacco smokers.[22] There was no benefit in subjects who had never smoked or had previously quit smoking.

In vitro, cultured skin and prostate cancer cells were suppressed (compared to nonmalignant cells) when treated with a combination of quercetin and ultrasound.[23]

Quercetin has been shown to increase the sensitivity of resistant colorectal tumors (CRC) with microsatellite instability (MSI) to the chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).[24]

Inflammation

Several laboratory studies show quercetin may have anti-inflammatory properties,[25][26] and it is being investigated for a wide range of potential health benefits.[26][27]

Quercetin has been reported to be of use in alleviating symptoms of pollinosis.[28] An enzymatically modified derivative was found to alleviate ocular but not nasal symptoms of pollinosis.[29][30][31]

A study with rats showed that quercetin effectively reduced immediate-release niacin(vitamin B3) flush, in part by means of reducing prostaglandin D2 production.[32] A pilot clinical study of four humans gave preliminary data supporting this.[33]

Metabolic syndrome

Quercetin has been shown to increase energy expenditure in rats, but only for short periods (fewer than 8 weeks).[25] Effects of quercetin on exercise tolerance in mice have been associated with increased mitochondrial biogenesis.[26] In mice, an oral quercetin dose of 12.5 to 25 mg/kg increased gene expression of mitochondrial biomarkers and improved exercise endurance.[34]

It has also been claimed that quercetin reduces blood pressure in hypertensive[35] and obese subjects in whom LDL cholesterol levels were also reduced.[36]

An in vitro study showed quercetin and resveratrol combined inhibited production of fat cells.[37]

A 12-week study of 941 adults found that supplements of 500 to 1000 milligrams of quercetin with vitamin C and niacin did not cause any significant difference in body mass or composition[38] and had no significant effect on inflammatory markers, diagnostic blood chemistries, blood pressure, and blood lipid profiles.[39]

Drug interactions

Quercetin is contraindicated with some antibiotics; it may interact with fluoroquinolones (an antibiotic), as quercetin competitively binds to bacterial DNA gyrase. Whether this inhibits or enhances the effect of fluoroquinolones is not certain.[40]

AHFS Drug Information (2010)[41] identifies quercetin as an inhibitor of CYP2C8, and specifically names it as a drug with potential to have harmful interactions with taxol/paclitaxel. As paclitaxel is metabolized primarily by CYP2C8, its bioavailability may be increased unpredictably, potentially leading to harmful side-effects.[42][43]

Quercetin is described as an inhibitor of CYP2C9.[44] Quercetin is an inhibitor[45] and inducer[46] of CYP3A4 (in other words, it reduces the enzyme's activity in the short term, but the body responds by producing more of it). CYP2C9 and CPY3A4 are members of the cytochrome P450 mixed-function oxidase system, and as such are enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics in the body. In either case, quercetin may alter serum levels and, therefore, effects of drugs metabolized by these enzymes.

References

- ^ "Quercetin". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Quercitin (biochemistry)". Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- ^ Christiane Fischer, Volker Speth, Sonja Fleig-Eberenz, and Gunther Neuhaus (1999-10). "lnduction of Zygotic Polyembryos in Wheat: lnfluence of Auxin Polar Transport" (PDF). Plant Cell. 9 (10): 1767–1780. doi:10.1105/tpc.9.10.1767. PMC 157020. PMID 12237347.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods

- ^ Crystal Smith, Kevin A. Lombard, Ellen B. Peffley, Weixin Liu (2003). "Genetic Analysis of Quercetin in Onion (Allium cepa L.) Lady Raider" (PDF). The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resource. 16. Agriculture Consortium of Texas: 24–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sari H. Häkkinen; et al. (1999). "Content of the Flavonols Quercetin, Myricetin, and Kaempferol in 25 Edible Berries". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (6): 2274–9. doi:10.1021/jf9811065. PMID 10794622.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ A. E. Mitchell, Y. J. Hong, E. Koh, D. M. Barrett, D. E. Bryant, R. F. Denison and S. Kaffka (2007). "Ten-Year Comparison of the Influence of Organic and Conventional Crop Management Practices on the Content of Flavonoids in Tomatoes". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (15): 6154–9. doi:10.1021/jf070344. PMID 17590007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Honey Research Unit

- ^ honey fingerprinting

- ^ Biosynthesis of quercetin.

- ^ Winkel-Shirley, Brenda (June 2001). "Flavonoid Biosynthesis. A Colorful Model for Genetics, Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Biotechnology". Plant Physiol. 126 (2): 485–493. doi:10.1104/pp.126.2.485. PMC 1540115. PMID 11402179.

- ^ Mullen W; et al. (2008). "Bioavailability of [2-(14)C]quercetin-4'-glucoside in rats". J Agric Food Chem. 2456 (24): 12127–37. doi:10.1021/jf802754s. PMID 19053221.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ US FDA, Center for Food Safety and Nutrition, Qualified Health Claims Subject to Enforcement Discretion, April 2007 [1] [dead link]

- ^ Wu, LL (03-27-2007). "In vivo and in vitro antiviral activity of hyperoside extracted from Abelmoschus manihot (L) medik". Acta Pharmacologica Sinica.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Yu, YB (07-30-2007). "Effects of triterpenoids and flavonoids isolated from Alnus firma on HIV-1 viral enzymes". Archives of Pharmacal Research.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ American Cancer Society, Quercetin

- ^ Verschoyle RD, Steward WP, Gescher AJ (2007). "Putative cancer chemopreventive agents of dietary origin-how safe are they?". Nutr Cancer. 59 (2): 152–62. doi:10.1080/01635580701458186. PMID 18001209.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rietjens IM, Boersma MG, van der Woude H, Jeurissen SM, Schutte ME, Alink GM (2005). "Flavonoids and alkenylbenzenes: mechanisms of mutagenic action and carcinogenic risk". Mutat. Res. 574 (1–2): 124–38. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.028. PMID 15914212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van der Woude H, Alink GM, van Rossum BE; et al. (2005). "Formation of transient covalent protein and DNA adducts by quercetin in cells with and without oxidative enzyme activity". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18 (12): 1907–16. doi:10.1021/tx050201m. PMID 16359181.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Neuhouser ML (2004). "Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: evidence from human population studies". Nutr Cancer. 50 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1207/s15327914nc5001_1. PMID 15572291.

- ^ Murakami A, Ashida H, Terao J (2008). "Multitargeted cancer prevention by quercetin". Cancer Lett. 269 (2): 315–25. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.046. PMID 18467024.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nöthlings U; et al. (2007). "Flavonols and pancreatic cancer risk". American Journal of Epidemiology. 166 (8): 924–931. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm172. PMID 17690219.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Paliwal S; Sundaram, J; Mitragotri, S (2005). "Induction of cancer-specific cytotoxicity towards human prostate and skin cells using quercetin and ultrasound". British Journal of Cancer. 92 (3): 499–502. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602364. PMC 2362095. PMID 15685239.

- ^ Xavier, Cristina (2011-04-10). "Quercetin enhances 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in MSI colorectal cancer cells through p53 modulation". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (0344–5704): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00280-011-1641-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b

Laura K. Stewart, Jeff L. Soileau, David Ribnicky, Zhong Q. Wang, Ilya Raskin, Alexander Poulev, Martin Majewski, William T. Cefalu, and Thomas W. Gettys (2008). "Quercetin transiently increases energy expenditure but persistently decreases circulating markers of inflammation in C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet". Metabolism. 57.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c J. Mark Davis, E. Angela Murphy, Martin D. Carmichael, and Ben Davis (2009), "Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance", Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 296

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Phys Ed: Is Quercetin Really a Wonder Sports Supplement? By Gretchen Reynolds. New York Times, October 7, 2009. Review of the research.

- ^ Balabolkin, II; Gordeeva, GF; Fuseva, ED; Dzhunelov, AB; Kalugina, OL; Khamidova, MM (1992). "Use of vitamins in allergic illnesses in children". Voprosy meditsinskoi khimii. 38 (5): 36–40. PMID 1492394.

- ^ Hirano, T; Kawai, M; Arimitsu, J; Ogawa, M; Kuwahara, Y; Hagihara, K; Shima, Y; Narazaki, M; Ogata, A (2009). "Preventative effect of a flavonoid, enzymatically modified isoquercitrin on ocular symptoms of Japanese cedar pollinosis". Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 58 (3): 373–82. doi:10.2332/allergolint.08-OA-0070. PMID 19454839.

- ^ Kawai, M; Hirano, T; Arimitsu, J; Higa, S; Kuwahara, Y; Hagihara, K; Shima, Y; Narazaki, M; Ogata, A (2009). "Effect of enzymatically modified isoquercitrin, a flavonoid, on symptoms of Japanese cedar pollinosis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial". International archives of allergy and immunology. 149 (4): 359–68. doi:10.1159/000205582. PMID 19295240.

- ^ Mainardi, T; Kapoor, S; Bielory, L (2009). "Complementary and alternative medicine: herbs, phytochemicals and vitamins and their immunologic effects". The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 123 (2): 283–94, quiz 295–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.023. PMID 19203652.

- ^ Papaliodis D, Boucher W, Kempuraj D, Theoharides TC (2008). "The flavonoid luteolin inhibits niacin-induced flush". Brit J Pharmacol. 153 (7): 1382–87. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707668. PMC 2437911. PMID 18223672.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kalogeromitros, D; Makris, M; Chliva, C; Aggelides, X; Kempuraj, D; Theoharides, TC (2008). "A quercetin containing supplement reduces niacin-induced flush in humans". International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 21 (3): 509–14. PMID 18831918.

- ^ Davis JM, Murphy EA, Carmichael MD, Davis B. (2009). "Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 296 (4): R1071–7. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.90925.2008. PMID 19211721.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edwards RL, Lyon T, Litwin SE, Rabovsky A, Symons JD, Jalili T (1 November 2007). "Quercetin reduces blood pressure in hypertensive subjects". J. Nutr. 137 (11): 2405–11. PMID 17951477.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Egert S; et al. (2009). "Quercetin reduces systolic blood pressure and plasma oxidised low-density lipoprotein concentrations in overweight subjects with a high-cardiovascular disease risk phenotype: A double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over study". Br J Nutr. 102 (7): 1065–1074. doi:10.1017/S0007114509359127. PMID 19402938.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Yang JY, Della-Fera MA, Rayalam S, Ambati S, Hartzell DL, Park HJ, Baile CA (2008). "Enhanced inhibition of adipogenesis and induction of apoptosis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes with combinations of resveratrol and quercetin". Life Sci. 82 (19–20): 1032–9. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2008.03.003. PMID 18433793.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Knab, AM; Shanely, RA; Jin, F; Austin, MD; Sha, W; Nieman, DC (2011). "Quercetin with vitamin C and niacin does not affect body mass or composition". Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme. 36 (3): 331–8. doi:10.1139/h11-015. PMID 21574787.

- ^ Knab, AM; Shanely, RA; Henson, DA; Jin, F; Heinz, SA; Austin, MD; Nieman, DC (2011). "Influence of quercetin supplementation on disease risk factors in community-dwelling adults". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (4): 542–9. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.01.013. PMID 21443986.

- ^ Hilliard JJ, Krause HM, Bernstein JI; et al. (1995). "A comparison of active site binding of 4-quinolones and novel flavone gyrase inhibitors to DNA gyrase". Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 390: 59–69. PMID 8718602.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.ahfsdruginformation.com/products_services/di_ahfs.aspx

- ^ Bun SS, Ciccolini J, Bun H, Aubert C, Catalin J (2003-06). "Drug interactions of paclitaxel metabolism in human liver microsomes". J Chemother. 15 (3): 266–74. PMID 12868554.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bun SS, Giacometti S, Fanciullino R, Ciccolini J, Bun H, Aubert C (2005–07). "Effect of several compounds on biliary excretion of paclitaxel and its metabolites in guinea-pigs". Anticancer Drugs. 16 (6): 675–82. doi:10.1097/00001813-200507000-00013. PMID 15930897.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Si Dayong, Wang Y, Zhou Y-H, Guo Y, Wang J, Zhou H, Li Z-S, Fawcett JP (2009). "Mechanism of CYP2C9 inhibition by flavones and flavonols" (PDF). Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 37 (3): 629–634. doi:10.1124/dmd.108.023416. PMID 19074529.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Su-Lan Hsiu; Yu-Chi Hou; Yao-Horng Wang; Chih-Wan Tsao; Sheng-Fang Sue; and Pei-Dawn L. Chao (6 December 2002). "Quercetin significantly decreased cyclosporin oral bioavailability in pigs and rats". Life Sciences. 72 (3): 227–235. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02235-X. PMID 12427482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Judy L. Raucy (1 May 2003). "Regulation of CYP3A4 Expression in Human Hepatocytes by Pharmaceuticals and Natural Products". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (3): 533–539. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.5.533. PMID 12695340.