Niominka people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Seereer-Siin |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| Serer proper, Cangin languages, Wolof French (Senegal and Mauritania), English (The Gambia), | |

| Religion | |

| Serer Religion, some practice Catholicism and a very small number practice Islam.[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Wolof people, Toucouleur people and Lebou people |

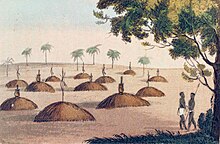

The Niominka people (also called Nyominka) are an ethnic group in Senegal living on the islands of the Saloum River.

They are a part of the Serer ethnic group and are closely related to the Guelowar of Sine-Saloum.

Population

Their territory is called the Gandoul. Most of the Niominka live in its eleven large villages, which include Niodior, Dionewar, and Falia.

They represent a little less than 1% of the population of Senegal. However, as part of the Serer people to which they belong, they collectively make up the third largest ethnic group in Senegal.[3] They are also found in The Gambia. Being island-dwellers, they participate in both agriculture and aquaculture. The primary agricultural produce is made up of rice, millet, and peanuts. As for the aquaculture, the men fish and the women gather shellfish. Unfortunately environmental problems have become an aquacultural threat. Therefore, the Niominka are also beginning to look into tourism.

Language

They speak a dialect of the Serer language also called Niominka.

History

The Serer people to which they belong are the oldest inhabitants of Senegambia along with the Jola people. Their Serer ancestors were dispersed throughout the Senegambian Region and it was them who built the megaliths of Senegambia.[4][5]

The Serer people are also the ancestors of the Wolof people, Lebou people and Toucouleur people.[6][7]

Their people, the Serer, were not only members of the royal dynasty of Takrur, High Priests and Priestess of the Kingdom's main religion, the land owners passed down through the "Lamanic" lineage (descendants of the original founders, kings and land owners - in Serer culture), but they also brought civilisation there more than two thousand years ago.

The following is a is a quote from the historian Henry Gravrand author of "La Civilisation Sereer, Pangool" as well as "La Civilisation Sereer, Cossan":

"Since the publication of "Cossan" (history), I took as a starting point of the Sereer (Serer) story in Tekrur over 2000 years ago, I noted an important discovery. In the middle of the Sahara, in the Tasili the rock carvings listed by Henri Lhote, appears the traces of the present "Sereer Cossan" (Serer history) or their ancestors, a period dating back to the third or fourth millennium. This engraving represents the Sereer initiation Star (Serer Cosmology), with two coiled snakes, symbols of the "Pangool" (ancestral spirits also ancient Serer Saints in the Serer Religion)... The rock where the Star appears is the Sereer symbols of the Pangool which was probably a place of worship."[8]

At Takrur, after several Serer victories against Islamization and Arabization, they were finally defeated by the Almoravid Islamic coalition - a coalition made up of Arab-Berbers and their African converts such as Toucouleurs and Fulas who were the first to convert and chose to abandon their religion. That was in 1035 AD during the reign of King War Jabi - a part Toucouleur, part Soninke and part Mandinka of the Manna (Manneh) Dynasty who launched a revolution against the ruling elite. At that time, War Jabi introduced Islamic Sharia law and after the final defeat of the Serer people of Takrur, the Serer still refused to submit to a foreign religion (Islam) but instead decided to move down south to join their distant relatives and preserve their honour. According to Elisa Daggs, only the powerful Serer tribes to whom the Serer-Niominka descended from resisted conversion whilst the others ethnic groups (i.e. the Toucouleurs and Fula who were also living at Takrur at the time with the Serers) easily submitted to the foreign invaders. The following is a quote from Elisa Daggs' book: "All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status":

"The Islamic religion which dominates Senegal today was carried from Mecca into North Africa after the seventh century by ... the Sahara by the Arabs and Arabized Berbers into Senegal. Only the powerful Serer tribes resisted conversion..."[9]

The Serer-Niominka also have Mandinka ancestors called the Guelowar, who came from Kaabu in the 14th century escaping the Battle of Turubang 1335. They were part of the royal dynasty of Kaabu and were being massacred by the Nyanthio dynasty of Kaabu.

Although the Nyanthios and Geulowars were relatives, the Battle of Turubang 1335 was a dynastic war between two maternal royal houses ("The House of Nyanthio" and "The House of Guelwar"). "Turubang" in Mandinka means to wipeout a clan or family.

After their defeat, their Mandinka ancestors escaped to the Serer Kingdom of Sine and were granted asylum by the Serer nobility of Sine. The Serer paternal noble families such as Faye (surname), Diouf or Joof, Njie or N'diaye etc, married the Guelowar women and it was the offsprings of these marriages that provided the Guelowar maternal dynasties and Serer paternal dynasties of the Kingdom of Sine (1350 AD) and later the Kingdom of Saloum (1494 AD). The dynasties of these respective Serer Kingdoms lasted upto 1969. That was 9 years after modern day Senegal gained its independence from France in 1960.[10][11][12]

Religion

They practice the Serer Religion which involves honouring the ancestors covering all dimensions of life, death, cosmology etc.[13][14]

See Also

Related Ethnic Groups and Dialect

Other Ethnic Groups

Serer Kingdoms

Serer Demographics

Presidents of Senegal

Notes

- ^ Joshua Project. Note that you may be directed to the Afghanistan page which is first alphabetically. Select Senegal under country and select Serer-Sine people.

- ^ Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. Estimated figures for 2007 in Senegal alone

- ^ Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie

- ^ Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool.Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. Page 77 ISBN:2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Gambian Studies No. 17. “People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof.” By David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie. San Francisco 1985

- ^ Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. By Alhaji Ebou Momar Taal. 2010

- ^ Gambian Studies No. 17. “People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof.” By David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie. San Francisco 1985

- ^ Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. Page 9. ISBN: 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Elisa Daggs. All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status. Hasting House, 1970. ISBN: 0803803362, 9780803803367

- ^ Alioune Sarr,Histoire du Sine-Saloum. Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3-4, 1986-1987

- ^ Martin A. Klein,Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847-1914, Edinburgh At the University Press (1968)

- ^ Lucie Gallistel Colvin. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ - London (1981) ISBN 081081885x

- ^ Issa Laye Thiaw. "La Religiosite de Seereer, Avant et pendant leur Islamisation". Ethiopiques no: 54, Revue semestrielle de Culture Négro-Africaine. Nouvelle série, volume 7, 2e Semestre 1991

- ^ Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. Page 9. ISBN: 2-7236-1055-1

Language Bibliography

English Language Bibliography

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Gambian Studies No. 17. “People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof.” By David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie. San Francisco 1985

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. By Alhaji Ebou Momar Taal. 2010

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Martin A. Klein,Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847-1914, Edinburgh At the University Press (1968)

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Lucie Gallistel Colvin. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ - London (1981) ISBN 081081885x

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Elisa Daggs. All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status. Hasting House, 1970. ISBN: 0803803362, 9780803803367

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Virginia Coulon (Spring 1973). "Niominka Pirogue Ornaments". African Arts. 6 (3): 26–31. doi:10.2307/3334691.

French Language Bibliography

- Template:Fr Issa Laye Thiaw. "La Religiosite de Seereer, Avant et pendant leur Islamisation". Ethiopiques no: 54, Revue semestrielle de Culture Négro-Africaine. Nouvelle série, volume 7, 2e Semestre 1991

- Template:Fr Alioune Sarr,Histoire du Sine-Saloum. Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3-4, 1986-1987

- Template:Fr Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool.Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. Page 77 ISBN:2-7236-1055-1

- Template:Fr Joseph Kerharo (1964). "Les plantes médicinales, toxiques et magiques des Niominka et des Socé des îles du Saloum (Sénégal)". Acta tropica (8): 279–334.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Template:Fr F. Lafont (1938). "Le Gandoul et les Niominkas". Bulletin du Comité d'Études Historiques et Scientifiques de 1'AOF. XXI (3): 385–450.

- Template:Fr Assane Niane (1995). Les Niominka de l’offensive musulmane en 1863 à l’établissement du protectorat français en 1891 : Le Gandun dans la maîtrise du royaume du Saalum. Dakar: Université Cheikh Anta Diop. p. 81.

- Template:Fr R. Van Chi Bonnardel (1977). "Exemple de migrations multiformes intégrées : les migrations de Nyominka (îles du Bas-Saloum sénégalais)". Bulletin de l'IFAN. B. 39 (4): 837–889.

Filmography

External links

- Ethnic groups in Senegal

- Ethnic groups in the Gambia

- Ethnic groups in Guinea-Bissau

- Ethnic groups in Mauritania

- Languages of Senegal

- Languages of the Gambia

- Languages of Mauritania

- Ethnic groups in Africa

- Languages of Africa

- History of Senegal

- History of the Gambia

- History of Mauritania

- History of Africa

- Prehistoric Africa

- History by ethnic group

- African royalty

- Sahelian kingdoms

- Animism

- Wars involving Senegal

- Military history of Africa

- Battles involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- African civilizations

- States of pre-colonial Africa

- French West Africa

- Islam-related controversies

- Islamic fundamentalism

- Islamism in Africa

- Jihad

- Islam and other religions

- History of Islam

- Serer people

- Serer language

- Serer history