Female genital mutilation

| Female genital mutilation | |

|---|---|

| Description | Partial or complete removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs, for non-medical reasons |

| Areas practiced | Western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, Middle East, Near East, Southeast Asia |

| Number affected | 135 million women and girls as of 1997 |

| Age performed | A few days after birth to age 15; occasionally in adulthood |

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."[1]

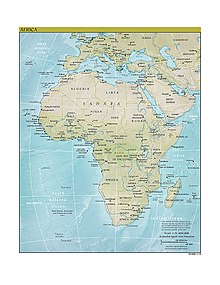

FGM is typically carried out on girls from a few days old to puberty. It may take place in a hospital, but is usually performed, without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser using a knife, razor, or scissors. According to the WHO, it is practised in 28 countries in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, in parts of Asia and the Middle East, and within some immigrant communities in Europe, North America, and Australasia.[2] The WHO estimates that 100–140 million women and girls around the world have experienced the procedure, including 92 million in Africa.[1]

The WHO has offered four classifications of FGM. The main three are Type I, removal of the clitoral hood, almost invariably accompanied by removal of the clitoris itself (clitoridectomy); Type II, removal of the clitoris and inner labia; and Type III (infibulation), removal of all or part of the inner and outer labia, and usually the clitoris, and the fusion of the wound, leaving a small hole for the passage of urine and menstrual blood—the fused wound is opened for intercourse and childbirth.[3] Around 85 percent of women who undergo FGM experience Types I and II, and 15 percent Type III, though Type III is the most common procedure in several countries, including Sudan, Somalia, and Djibouti.[4] Several miscellaneous acts are categorized as Type IV. These range from a symbolic pricking or piercing of the clitoris or labia, to cauterization of the clitoris, cutting into the vagina to widen it (gishiri cutting), and introducing corrosive substances to tighten it.[3]

Opposition to FGM focuses on human rights violations, lack of informed consent, and health risks, which include epidermoid cysts, recurrent urinary and vaginal infections, chronic pain, and obstetrical complications. Since 1979, there have been concerted efforts by international bodies to end the practice, including sponsorship by the United Nations of an International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation, held each February 6 since 2003.[5] Sylvia Tamale, an African legal scholar, writes that there is a large body of research and activism in Africa itself that strongly opposes FGM, but she cautions that some African feminists object to what she calls the imperialist infantilization of African women, and they reject the idea that FGM is nothing but a barbaric rejection of modernity. Tamale suggests that there are cultural and political aspects to the practice's continuation that make opposition to it a complex issue.[6]

Background

Terminology

The procedures known as FGM were referred to as female circumcision until the early 1980s, when the term "female genital mutilation" came into use.[7] The term was adopted at the third conference of the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and in 1991 the WHO recommended its use to the United Nations.[2] It has since become the dominant term within the international community and in medical literature.[4] Alexia Lewnes argued in a 2005 report for UNICEF that the word "mutilation" differentiates the procedure from male circumcision and stresses its severity.[8]

Other terms in use, apart from female circumcision, include female genital cutting (FGC), female genital surgeries, female genital alteration, female genital excision, and female genital modification.[9] Elizabeth Heger Boyle writes that some organizations refer to it as female genital cutting because that is better received in the communities that practise it, who do not see themselves as engaging in mutilation; she writes that state-sponsored groups tend to call it FGM while private groups use FGC.[10] Other groups, such as UNFPA and USAID, use the combined term "female genital mutilation/cutting" (FGM/C).[11]

Local terms for the procedure include tahara in Egypt; tahur in Sudan; and bolokoli in Mali, which Anika Rahman and Nahid Toubia write are words synonymous with purification. Several countries refer to Type 1 FGM as sunna circumcision.[12] It is also known as kakia, and in Sierra Leone as bundu, after the Bundu secret society.[13] Type III FGM (infibulation) is known as "pharaonic circumcision" in Sudan, and as "Sudanese circumcision" in Egypt.[14] Urologist Jean Fourcroy writes that women in countries that practise FGM call it one of the "three feminine sorrows": the first sorrow is the procedure itself, followed by the wedding night when a woman with Type III has to be cut open, then childbirth when she has to be cut again.[15][16][17]

The term FGM is not applied to medical or elective procedures such as labiaplasty and vaginoplasty, or those used in sex reassignment surgery. According to the WHO, some practices regarded as legal in countries that have outlawed FGM do fall under the category of Type IV (see below), but the organization decided to maintain a broad definition to avoid loopholes that could allow FGM to continue.[2]

History and cultural context

FGM is considered by its practitioners to be an essential part of raising a girl properly—girls are regarded as having been cleansed by the removal of "male" body parts. It ensures pre-marital virginity and inhibits extra-marital sex, because it reduces women's libido. Women fear the pain of re-opening the vagina, and are afraid of being discovered if it is opened illicitly.[1]

The term "pharaonic circumcision" (Type III) stems from its practice in Ancient Egypt under the Pharaohs, and "fibula" (in "infibulation") refers to the Roman practice of piercing the outer labia with a fibula, or brooch.[19] Leonard Kuber and Judith Muascher write that circumcised females have been found among Egyptian mummies, and that Herodotus (c. 484 BCE – c. 425 BCE) referred to the practice when he visited Egypt. There is reference on a Greek papyrus from 163 BCE to the procedure being conducted on girls in Memphis, the ancient Egyptian capital, and Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 23 CE), the Greek geographer, reported it when he visited Egypt in 25 BCE.[18]

Asim Zaki Mustafa argues that the common attribution of the procedure to Islam is unfair because it is a much older phenomenon.[20] While individual Muslims, Christians, and Jews practise FGM, it is not a requirement of any religious observance. Judaism requires circumcision for boys, but does not allow it for girls.[21] Islamic scholars have said that, while male circumcision is a sunna, or religious obligation, female circumcision is preferable but not required, and several have issued a fatwa against Type III FGM.[22]

Sudanese surgeon Nahid Toubia—president of RAINBO (Research, Action and Information Network for the Bodily Integrity of Women) —told the BBC in 2002 that campaigning against FGM involved trying to change women's consciousness: "By allowing your genitals to be removed [it is perceived that] you are heightened to another level of pure motherhood—a motherhood not tainted by sexuality and that is why the woman gives it away to become the matron, respected by everyone. By taking on this practice, which is a woman's domain, it actually empowers them. It is much more difficult to convince the women to give it up, than to convince the men."[23][24] Boyle writes that the Masai of Tanzania will not call a woman "mother" when she has children if she is uncircumcised.[25]

According to Amnesty, in certain societies women who have not had the procedure are regarded as too unclean to handle food and water, and there is a belief that a woman's genitals might continue to grow without FGM, until they dangle between her legs. Some groups see the clitoris as dangerous, capable of killing a man if his penis touches it, or a baby if the head comes into contact with it during birth, though Amnesty cautions that ideas about the power of the clitoris can be found elsewhere.[26] Gynaecologists in England and the United States would remove it during the 19th century to "cure" insanity, masturbation, and nymphomania.[27] The first reported clitoridectomy in the West was carried out in 1822 by a surgeon in Berlin on a teenage girl regarded as an "imbecile" who was masturbating.[28][29] Isaac Baker Brown (1812–1873), an English gynaecologist who was president of the Medical Society of London in 1865, believed that the "unnatural irritation" of the clitoris caused epilepsy, hysteria, and mania, and would remove it "whenever he had the opportunity of doing so," according to an obituary. Peter Lewis Allen writes that his views caused outrage—or, rather, his public expression of them did—and Brown died penniless after being expelled from the Obstetrical Society.[30]

Classification and health consequences

The age at which the procedure is performed varies. Comfort Momoh, a specialist midwife in England, writes that in Ethiopia the Falashas perform it when the child is a few days old, the Amhara on the eighth day of birth, while the Adere and Oromo choose between four years and puberty. In Somalia it is done between four and nine years. Other communities may wait until adulthood, she writes, either just before marriage or just after the first pregnancy. The procedure may be carried out on one girl alone, or on a group of girls at the same time.[31] It is generally performed by a traditional circumciser, usually an older woman known as a "gedda," without anaesthesia or sterile equipment, though richer families may pay instead for the services of a nurse, midwife, or doctor using a local anaesthetic. It may also be performed by the mother or grandmother, or in some societies—such as Nigeria and Egypt—by the local male barber.[28]

The WHO divides FGM into four categories (see image right for types I–III).[2] Around 85 percent of women experience Types I and II, and 15 percent Type III, though Martha Nussbaum writes that Type III nevertheless accounts for 80–90 percent of all such procedures in countries such as Sudan, Somalia, and Dijbouti.[4]

Types I and II

Known in several communities as sunna circumcision, Type I is the removal of the clitoral hood (Type Ia); or the partial or total removal of the clitoris, a clitoridectomy (Type Ib).[2] Type II, often called excision, is partial or total removal of the clitoris and the inner labia or outer labia. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia only; Type IIb, partial or total removal of the clitoris and the inner labia; and Type IIc, partial or total removal of the clitoris, and the inner and outer labia.[2]

Type III

Type III, commonly called infibulation or pharaonic circumcision, is the removal of all external genitalia. The inner and outer labia are cut away, with or without excision of the clitoris.[32] The girl's legs are then tied together from hip to ankle for around 40 days to allow the wound to heal. The immobility causes the labial tissue to bond, forming a wall of flesh and skin across the entire vulva, apart from a hole the size of a matchstick for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, which is created by inserting a twig or rock salt into the wound.[14][33][34][35][36] There is another form of Type III called matwasat, where the stitching of the vulva is less extreme and the hole left is bigger.[19] Momoh describes a Type III procedure in Female Genital Mutilation (2005):

In Type 3 excision or infibulation ... elderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the lithotomy position. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the fourchette, and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora.

Bleeding is profuse, but is usually controlled by the application of various poultices, the threading of the edges of the skin with thorns, or clasping them between the edges of a split cane. A piece of twig is inserted between the edges of the skin to ensure a patent foramen for urinary and menstrual flow. The lower limbs are then bound together for 2–6 weeks to promote haemostatis and encourage union of the two sides...

Healing takes place by primary intention, and, as a result, the introitus is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture.[3]

The vulva is cut open for sexual intercourse and childbirth. Momoh writes that, in some communities, when a pregnant woman who has not experienced FGM goes into labour, the procedure is performed before she gives birth, because it is believed the baby may be stillborn if it touches her clitoris. The risk of haemorrhage and death from FGM during labour is high, she writes.[37] During three six-month studies in the 1980s, Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed 300 Sudanese women and 100 Sudanese men, and described the penetration by the men of their wives' infibulation:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. A great deal of marital anal intercourse takes place in cases where the wife can not be penetrated—quite logically in a culture where homosexual anal intercourse is a commonly accepted premarital recourse among men—but this is not readily discussed. Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife." This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis. In some women, the scar tissue is so hardened and overgrown with keloidal formations that it can only be cut with very strong surgical scissors, as is reported by doctors who relate cases where they broke scalpels in the attempt.[38]

Type IV

A variety of other procedures are collectively known as Type IV, which the WHO defines as "all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization." This ranges from ritual nicking of the clitoris—the main practice in Indonesia—to stretching the clitoris or labia, burning or scarring the genitals, or introducing harmful substances into the vagina to tighten it.[2] It also includes hymenotomy, the removal of a hymen regarded as too thick, and gishiri cutting, a practice in which the vagina's anterior wall is cut with a knife to enlarge it.[19]

Immediate and late complications

FGM is typically carried out by traditional practitioners, without anaesthesia, using unsterile cutting devices such as knives, razors, scissors, cut glass, sharpened rocks, and fingernails, and applying suturing material such as agave or acacia thorns.[39][40] Affluent people in urban settings may have the procedure done in a safer medical environment.

FGM has immediate and late complications. Immediate complications are increased when FGM is performed in traditional ways, and without access to medical resources: the procedure is extremely painful and a bleeding complication can be fatal. Other immediate complications include acute urinary retention, urinary infection, wound infection, septicemia, tetanus, and in case of unsterile and reused instruments, hepatitis and HIV.[39] According to Lewnes' UNICEF report, it is unknown how many girls and women die from the procedure because "few records are kept" and fatalities caused by FGM "are rarely reported as such".[41] Momoh says the short-term mortality rate is around 10 percent, due to complications such as infection, haemorrhage, and hypovolemic shock.[42] A film shot in Lunsar, Sierra Leone, by Mariana van Zeller in 2007 discusses how girls who bleed excessively are regarded as witches.[43]

Late complications may vary depending on the type of FGM performed.[39] The formation of scars and keloids can lead to strictures, obstruction or fistula formation of the urinary and genital tracts. Urinary tract sequalae include damage to urethra and bladder with infections and incontinence. Genital tract sequelae include vaginal and pelvic infections, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.[40] Complete obstruction of the vagina results in hematocolpos and hematometra.[39] Other complications inlude epidermoid cysts that may become infected, neuroma formation, typically involving nerves that supplied the clitoris, and pelvic pain.[44]

FGM may complicate pregnancy and place women at higher risk for obstetrical problems, which are more common with the more extensive FGM procedures.[39] Thus, in women with Type III FGM who have developed vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae—holes that allows urine and feces to seep into the vagina—it is difficult to obtain clear urine samples as part of prenatal care making the diagnosis of certain conditions harder, such as preeclampsia.[40] Cervical evaluation during labour may be impeded, and labour prolonged. Third-degree laceration, anal sphincter damage, and emergency caesarean section are more common in FGM women than in controls.[39] Neonatal mortality is increased in women with FGM. The WHO estimated that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM; the estimate was based on a 2006 study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centers in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II, and 55 percent for Type III.[32]

Psychological complications are related to cultural context; damage may occur to women who undergo FGM particularly when they are moving outside their traditional circles and are confronted with a view that mutilation is not the norm.[39] Women with FGM typically report sexual dysfunction and dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), but several researchers have written that FGM does not necessarily destroy sexual desire in women. Elizabeth Heger Boyle reported several studies during the 1980s and 1990s where the women said they were able to enjoy sex, though with Type III the risk of sexual dysfunction was higher.[45]

Reinfibulation and defibulation

Women may request reinfibulation (RI)—the restoration of the infibulation—after birth, a contentious issue, with surgeons who perform the procedure regarded as behaving unethically and probably illegally.[46] In Sudan, RI is known as El-Adel (re-circumcision or, literally, "putting right" or "improving"). Two cuts are made around the vagina, then sutures are put in place to tighten it to the size of a pinhole. Vanja Bergrren writes that this in effect mimics virginity. RI may also be carried out just before marriage, after divorce, or even in elderly women to prepare them for death.[47][48][49]

Defibulation, or deinfibulation, is a surgical technique to reverse the closure of the vaginal opening after a Type III infibulation, and consists of a vertical cut opening up normal access to the vagina.[50] This may be accompanied by removal of scar tissue and labial repair. Procedures have been developed to repair clitoral integrity, such as by Pierre Foldes, a French urologist and surgeon, and Marci Bowers, an American surgeon who studied his work; they used intact clitoral tissue from inside women's bodies to form a new clitoris.[51]

Prevalence and attempts to end the practice

Practising countries

According to the WHO, 100–140 million women and girls are living with FGM, including 92 million girls over the age of 10 in Africa.[1] The practice persists in 28 African countries, as well as in the Arabian Peninsula, where Types I and II are more common. It is known to exist in northern Saudi Arabia, southern Jordan, northern Iraq (Kurdistan), and possibly Syria, western Iran, and southern Turkey.[52] It is also practised in Indonesia, but largely symbolically by pricking the clitoral hood or clitoris until it bleeds.[53]

Several African countries have enacted legislation against it, including Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Djibouti, Eritrea, Togo, and Uganda.[54] President Daniel Moi of Kenya issued a decree against it in December 2001.[55] In Mauritania, where almost all the girls in minority communities undergo FGM, 34 Islamic scholars signed a fatwa in January 2010 banning the practice.[56]

In Egypt, the health ministry banned FGM in 2007 despite pressure from some (though not all) Islamic groups. Two issues in particular forced the government's hand. A 10-year-old girl was photographed undergoing FGM in a barber's shop in Cairo in 1995 and the images were broadcast by CNN; this triggered a ban on the practice everywhere except in hospitals. Then, in 2007, 12-year-old Badour Shaker died of an overdose of anaesthesia during or after an FGM procedure for which her mother had paid a physician in an illegal clinic the equivalent of $9.00. The Al-Azhar Supreme Council of Islamic Research, the highest religious authority in Egypt, issued a statement that FGM had no basis in core Islamic law, and this enabled the government to outlaw it entirely.[57][58][59]

Colonial opposition

Anika Rahman and Nahid Toubia write that attempts in the early 20th century by colonial administrators to halt FGM succeeded only in provoking local anger.[60] In Kenya, Christian missionaries in the 1920s and 1930s forbade their adherents from practising it—in part because of the medical consequences, but also because the accompanying rituals were seen as highly sexualized—and as a result it became a focal point of the independence movement among the Kikuyu, the country's main ethnic group.[61][62] One American missionary, Hilda Stump, was murdered in January 1930 after speaking out against it.[63] Lynn M. Thomas, the American historian, writes that the period 1929–1931 became what is known in Kenyan historiography as the female circumcision controversy. Protestant missionaries campaigning against it tried to gain support from humanitarian and women's rights groups in London, where the issue was raised in the House of Commons, and in Kenya itself a person's stance toward FGM became a test of loyalty, either to the Christian churches or to the Kikuyu Central Association.[64] Jomo Kenyatta (c. 1894–1978), who became Kenya's first prime minister in 1963, wrote in 1930:

The real argument lies not in the defense of the general surgical operation or its details, but in the understanding of a very important fact in the tribal psychology of the Kikuyu—namely, that this operation is still regarded as the essence of an institution which has enormous educational, social, moral and religious implications, quite apart from the operation itself. For the present it is impossible for a member of the tribe to imagine an initiation without clitoridoctomy [sic]. Therefore the ... abolition of the surgical element in this custom means ... the abolition of the whole institution.[65]

Support for the practice also came from the women themselves. E. Mary Holding, a Methodist missionary in Meru, Kenya, wrote in 1942 that the circumcision ritual was an entirely female affair, organized by women's councils known as kiama gia ntonye ("the council of entering"). The ritual not only saw the girls become women, but also allowed their mothers to become members of the council, a position of some authority.[64]

Similarly, prohibition strengthened tribal resistance to the British in the 1950s, and increased support for the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960).[66] In 1956, under pressure from the British, the council of male elders (the Njuri Nchecke) in Meru, Kenya, announced a ban on clitoridectomy. Over two thousand girls—mostly teenagers but some as young as eight—were charged over the next three years with having circumcised each other with razor blades, a practice that came to be known as Ngaitana ("I will circumcise myself"), so-called because the girls claimed to have cut themselves to avoid naming their friends.[64] Sylvia Tamale argues that this was done not only in defiance of the council's cooperation with the colonial authorities, but also in protest against its interference with women's decisions about their own rituals.[67][68] Thomas describes the episode as significant in the history of FGM because it made clear that its apparent victims were in fact its central actors.[64]

Since the 1960s

In the 1960s and 1970s, Rahman and Nahid Toubia write, doctors in Sudan, Somalia, and Nigeria began to speak out about the health consequences of FGM, and opposition gathered pace during the United Nations Decade for Women (1975–1985). In 1979 the American feminist writer Fran Hosken (1920–2006) presented research about it—The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females—to the first Seminar on Harmful Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, sponsored by the WHO. Rahman and Toubia write that African women from several countries at the conference led a vote to end the practice.[60]

In 1980 and 1982 feminist physicians Nawal El Saadawi and Asma El Dareer wrote about FGM as a dangerous practice intended to control women's sexuality.[64] The decade also saw the framing of FGM—along with other issues in the domestic sphere, such as dowry deaths—as a human rights violation, rather than as a health concern, and this encouraged academic interest, including from feminist legal scholars.[60] In June 1993 the Vienna World Conference on Human Rights agreed that FGM was a violation of human rights.[46]

Some of the international opposition to FGM continues to attract critics. The Hosken Report, in particular, was criticized for its alleged ethnocentrism, its negative statements about African society, and its insistence on Western intervention.[63] Sylvia Tamale wrote in 2011 that some African feminists interpret traditional practices such as FGM within a post-colonial context that makes opposing them a complex issue. While critical of FGM, they object to what Tamale calls the imperialist infantilization of African women inherent in the idea that FGM is simply a barbaric rejection of enlightenment and modernity.[69]

Lynn Thomas writes that the ritual of FGM has been the primary context in some communities in which the women come together. Because they see it as a way of elevating themselves from girlhood to womanhood, and thereby a way of differentiating between each other, Thomas argues that to remove FGM is to remove that opportunity to gain authority. She writes that the "eradicationists" have responded to these criticisms by reaching out to the African communities and strengthening their relationships with local anti-FGM activists.[64] For example, one of the issues that keeps FGM going in some communities is that the practitioners have no other way to earn a living. Organizations working to end it are therefore offering the women training of some kind; teaching them how to become farmers, for example.[70]

The organization Tostan [71] provides a basic education program to African communities. Although ending FGM was not one of Tostan's initial objectives, it has become a rallying point for Tostan participants, leading many participants and their communities and social networks to publicly abandon this harmful tradition. As of July 2011, 6,236 communities in seven countries have abandoned female genital mutilation.

Non-practicing countries

As a result of immigration, FGM spread to Australia, Europe, New Zealand, the United States and Canada. As Western governments became more aware of the practice, legislation was passed to make it a criminal offence, though enforcement may be a low priority. Sweden passed legislation in 1982, the first Western country to do so.[72] It is outlawed in New Zealand[73] and in most Australian states and territories, and is a crime under section 268 of the Criminal Code of Canada.[74] It became illegal in the United States on 30 March 1997, though according to a U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimate, 168,000 girls living there as of 1997 had undergone it or are at risk.[75] Nineteen-year-old Fauziya Kasinga, a member of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu tribe of Togo, was granted asylum in 1996 after leaving an arranged marriage to escape FGM, setting a precedent in U.S. immigration law because FGM was for the first time accepted as a form of persecution.[76]

In the UK, the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985 outlawed the procedure in Britain itself, and the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 and Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 made it an offence for FGM to be performed anywhere in the world on British citizens or permanent residents.[77] The Times reported in 2009 that there are 500 victims of FGM every year in the UK, but there have been no prosecutions. According to the Foundation for Women's Health, Research and Development, 66,000 women in England and Wales have experienced FGM, with 7,000 girls at risk. Families who have immigrated from practising countries may send their daughters there to undergo FGM, ostensibly to visit a relative, or may fly in circumcisers, known as "house doctors" because they conduct the procedure in people's homes.[78] The Guardian writes that the six-week-long school summer holiday in the UK is the most dangerous time of the year for these girls, a convenient time to carry out the procedure because they need several weeks to heal before returning to school.[77]

Notes

Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: Missing ISBN.

- ^ a b c d "Female genital mutilation", World Health Organization, February 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008, pp. 4, 22–28.

- See p. 4, and Annex 2, p. 24, for the basic classification into Types I, II, III, and IV.

- See Annex 1, p. 22, for the adoption of the term "female genital mutilation".

- See Annex 2, p. 23–28, for a more detailed discussion of the classification.

- See Annex 2, p. 24, for a discussion of Type IV.

- ^ a b c Momoh, Comfort (ed). Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing, 2005, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Martha Craven (1999). "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation". Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–20. ISBN 978-0-19-511032-6.

- ^ Feldman-Jacobs, Charlotte. "Commemorating International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation", Population Reference Bureau, February 2009.

- ^ Tamale, Sylvia. African Sexualities: A Reader. Fahamu/Pambazuka, 2011, pp. 19–20, 78, 89–90.

- ^ Rahman, Anika and Toubia, Nahid. Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide. Zed Books, 2000, p. x.

- ^ Lewnes, Alexia (ed). "Changing a harmful social convention: female genital cutting/mutilation", Innocenti Digest, UNICEF, 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ^ For "female genital modification," see Gallo, Pia Grassivaro; Tita Eleanora; and Viviani, Franco. "At the Roots of Ethnic Female Genital Modification," in Denniston, George C. and Gallo, Pia Grassivaro. Bodily Integrity and the Politics of Circumcision. Springer, 2006, pp. 49–50.

- For the rest, see Momoh 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Boyle, Elizabeth Heger. Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Conflict in the Global Community. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002, p. 60ff.

- Also see Shell-Duncan, Bettina and Hernlund, Ylva (eds). Female "Circumcision" in Africa. Lynne Rienner, 2000, p. 6.

- ^ "Annex to USAID Policy on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Explanation of Terminology", USAID, 2000.

- ^ Rahman and Toubia 2000, p. 4.

- ^ For kakia, see Kasinga, Fauziya and Bashir, Layli Miller. Do They Hear You When You Cry. Delacorte Press, 1998, p. 2.

- For bundu, see "Female genital mutilation in Sierra Leone", Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, accessed 9 September 2011.

- For a discussion of bundu with local practitioners, see Van Zeller, Mariana. "Female Genital Cutting", Vanguard, Current TV, 31 January 2007.

- ^ a b Elmusharaf, S.; Elhadi, N; Almroth, L (2006). "Reliability of self reported form of female genital mutilation and WHO classification: cross sectional study". BMJ. 333 (7559): 124. doi:10.1136/bmj.38873.649074.55. PMC 1502195. PMID 16803943.

- ^ Fourcroy, Jean L. "Female Circumcision", American Family Physician, August 1999

- ^ Fourcroy, JL (1998). "The three feminine sorrows". Hospital practice. 33 (7): 15–6, 21. PMID 9679503.

- ^ Momoh 2005, pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b Kouba, L. J.; Muasher, J. (1985). "Female Circumcision in Africa: An Overview". African Studies Review. 28 (1): 95–110. doi:10.2307/524569. JSTOR 524569.

- ^ a b c James, Stanlie M. "Female Genital Mutilation," in Smith, Bonnie G. The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 260–262.

- ^ Mustafa, Asim Zaki (1966). "Female Circumcision and Infibulation in the Sudan". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 73 (2): 302. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1966.tb05163.x.

- ^ "Circumcision", in Werblowsky, R. J. Zwi and Wigoder, Geoffrey (eds). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- ^ Gruenbaum, Ellen. The Female Circumcision Controversy. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001, p. 63.

- ^ "Changing attitudes to female circumcision", BBC News, 8 April 2002.

- ^ Shetty, Priya (2007). "Nahid Toubia". The Lancet. 369 (9564): 819. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60394-8.

- ^ Boyle 2002, p. 37.

- ^ "What is female genital mutilation?, Amnesty International, AI Index: ACT 77/06/97, accessed September 3, 2011.

- ^ Momoh 2005, p. 5.

- ^ a b Elchalal, Uriel; Ben-Ami, Barbara; Gillis, Rebecca; Brzezinski, Amnon (1997). "Ritualistic Female Genital Mutilation: Current Status and Future Outlook". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 52 (10): 643–51. doi:10.1097/00006254-199710000-00022. PMID 9326757.

- ^ Black, Donald Campbell. On the Functional Diseases of the Renal, Urinary and Reproductive organs. Lindsay & Blakiston, 1872, p. 216.

- ^ Allen, Peter L. The Wages of Sin: Sex and Disease, Past and Present. University of Chicago Press, 2000, p. 106.

- Brown, Isaac Baker. On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females. Robert Hardwicke, 1866.

- ^ Momoh 2005, p. 2.

- ^ a b WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome; Banks, E; Meirik, O; Farley, T; Akande, O; Bathija, H; Ali, M (2006). "Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries". Lancet. 367 (9525): 1835–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. PMID 16753486.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting (FGC): Individual Country Reports", U.S. Department of State, 1 June 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Momoh 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Pieters, G; Lowenfels, AB (1977). "Infibulation in the horn of Africa". New York state journal of medicine. 77 (5): 729–31. PMID 265433.

- ^ Gollaher, David. "Female Circumcision," Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery. Basic Books, 2001, pp. 187–207; see p. 191 for the description: A French doctor, Jacques Lantier, who attended an FGM procedure in Somalia in the 1970s described how the inner and outer labia were separated and attached to each thigh using large thorns. "With her kitchen knife the woman then pierces and slices open the hood of the clitoris and then begins to cut it out. While another woman wipes off the blood with a rag, the operator digs with her fingernail a hole the length of the clitoris to detach and pull out that organ. The little girls screams in extreme pain, but no one pays the slightest attention."

After removing the clitoris with the knife, the woman "lifts up the skin that is left with her thumb and index finger to remove the remaining flesh. She then digs a deep hole amidst the gushing blood. The neighbor women who take part in the operation then plunge their fingers into the bloody hole to verify that every remnant of the clitoris is removed."

- ^ Momoh 2005, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Lightfoot-Klein, H. (1989). "The Sexual Experience and Marital Adjustment of Genitally Circumcised and Infibulated Females in the Sudan". The Journal of Sex Research. 26 (3): 375–392. doi:10.1080/00224498909551521. JSTOR 3812643.

- ^ a b c d e f g . doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13137.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Kelly, Elizabeth; Hillard, Paula J Adams (2005). "Female genital mutilation". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 17 (5): 490–4. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000183528.18728.57. PMID 16141763.

- ^ Lewnes, Alexia (ed). "Changing a harmful social convention: female genital cutting/mutilation", Innocenti Digest, UNICEF, 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Momoh 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Van Zeller, Mariana. "Female Genital Cutting", Vanguard, Current TV, 31 January 2007, from 5:05 mins.

- ^ Dave, Amish J.; Sethi, Aisha; Morrone, Aldo (2011). "Female Genital Mutilation: What Every American Dermatologist Needs to Know". Dermatologic Clinics. 29 (1): 103–9. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.09.002. PMID 21095534.

- ^ Boyle 2002, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Toubia, Nahid (1994). "Female Circumcision as a Public Health Issue". New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (11): 712–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM199409153311106. PMID 8058079.

- ^ Berggren, V.; Musa Ahmed, S.; Hernlund, Y.; Johansson, E.; Habbani, B.; Edberg, A. K. (2006). "Being Victims or Beneficiaries? Perspectives on Female Genital Cutting and Reinfibulation in Sudan". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 10 (2): 24–36. doi:10.2307/30032456. PMID 17217115.

- ^ Berggren, V; Abdelsalam, G; Bergstrom, S; Johansson, E; Edberg, A (2004). "An explorative study of Sudanese midwives? Motives, perceptions and experiences of re-infibulation after birth". Midwifery. 20 (4): 299–311. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2004.05.001. PMID 15571879.

- ^ Serour, Gamal I. (2010). "The issue of reinfibulation". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 109 (2): 93–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.001.

- ^ Nour, Nawal M.; Michels, Karin B.; Bryant, Ann E. (2006). "Defibulation to Treat Female Genital Cutting". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 108: 55–60. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000224613.72892.77.

- ^ Conant, Eve. "The Kindest Cut", Newsweek, 27 October 2009.

- Foldes, Pierre. "Surgical Repair of the Clitoris after Ritual Genital Mutilation: Results of 453 Cases", WAS Visual, accessed 17 September 2011.

- ^ Birch, Nicholas. "Female circumcision surfaces in Iraq", Christian Science Monitor, 10 August 2005.

- ^ "Indonesia: Report on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting (FGC)", U.S. Department of State, 1 June 2001.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting (FGC): Individual Country Reports", U.S. Department of State, 1 June 2001.

- ^ Momoh 2005, p. 15.

- ^ "Mauritania fatwa bans female genital mutilation", BBC News, 18 January 2010.

- For the situation in Mauritania, see Momoh 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Michael, Maggie. "Egypt Officials Ban Female Circumcision", The Associated Press, 29 June 2007.

- ^ Kandela, P (1995). "Egypt sees U turn on female circumcision". BMJ. 310 (6971): 12. PMID 7827544.

- ^ "Fresh progress toward the elimination of female genital mutilation and cutting in Egypt", UNICEF, 2 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Rahman and Toubia 2000, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Natsoulas, T. (1998). "The Politicization of the Ban on Female Circumcision and the Rise of the Independent School Movement in Kenya: The KCA, the Missions and Government, 1929-1932". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 33 (2): 137. doi:10.1177/002190969803300201.

- ^ Strayer, Robert and Murray, Jocelyn. "The CMS and Female Circumcision", in Strayer, Robert. The Making of Missionary Communities in East Africa. Heinemann Educational Books, 1978, p. 36ff.

- ^ a b Abusharaf, Rogaia Mustafa. "Revisiting Feminist Discourses on Inbulation: The Hosken Report", in Shell-Duncan and Hernlund 2000, pp. 160–163.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thomas, Lynn M. "'Ngaitana (I will circumcise myself)': Lessons from Colonial Campaigns to Ban Excision in Meru, Kenya", in Shell-Duncan and Hernlund 2000, p. 129ff.

- ^ Mufaka, Kenneth. "Scottish Missionaries and the Circumcision Controversy in Kenya, 1900–1960", International Review of Scottish Studies, vol 28, 2003.

- ^ Birch, Nicholas. "An End to Female Genital Cutting?", Time magazine, 4 January 2008.

- ^ Tamale 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Thomas, Lynn M. (1996). ""Ngaitana (I will circumcise myself)": The Gender and Generational Politics of the 1956 Ban on Clitoridectomy in Meru, Kenya". Gender & History. 8 (3): 338. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.1996.tb00062.x.

- ^ Tamale 2011, pp. 19–20, 78.

- ^ Van Zeller, Mariana. "Female Genital Cutting", Vanguard, Current TV, 31 January 2007, from 5:25 mins.

- ^ "Tostan Organization".

- ^ Essen, Birgitta and Johnsdottir, Sara. "Female genital mutilation in the West: traditional circumcision versus genital cosmetic surgery", Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica, vol 28, 2004, pp. 611–613. PMID 15225183.

- ^ "Section 204A - Female genital mutilation - Crimes Act 1961". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ For New Zealand and Australia, see Rahman and Toubia 2000, pp. 102–103, 191.

- For Canada, see "Family Violence: Department of Justice Canada Overview paper", Department of Justice, 31 July 2007, footnote 4.

- ^ Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn. "Female genital mutilation", Encyclopedia of women's history in America, Infobase Publishing, 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Dugger, Celia W. "June 9-15; Asylum From Mutilation", The New York Times, 16 June 1996.

- "In re Fauziya KASINGA, file A73 476 695, U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review, decided 13 June 1996.

- Dugger, Celia W. "Woman's Plea for Asylum Puts Tribal Ritual on Trial", The New York Times, 15 April 1996.

- ^ a b McVeigh, Tracy and Sutton, Tara. "British girls undergo horror of genital mutilation despite tough laws", The Guardian, 25 July 2010.

- ^ Kerbaj, Richard. "Thousands of girls mutilated in Britain", The Times, 16 March 2009.

References

- Books

- Boyle, Elizabeth Heger. Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Conflict in the Global Community. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Allen, Peter Lewis. The Wages of Sin: Sex and Disease, Past and Present. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Momoh, Comfort. Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing, 2005.

- Gollaher, David. "Female Circumcision," Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery. Basic Books, 2000.

- Gruenbaum, Ellen. The Female Circumcision Controversy. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Kasinga, Fauziya, and Bashir, Layli Miller. Do They Hear You When You Cry. Delacorte Press, 1998.

- Nussbaum, Martha Craven. "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation," Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Rahman, Anika and Toubia, Nahid. Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide. Zed Books, 2000.

- Shell-Duncan, Bettina and Hernlund, Ylva (eds). Female "Circumcision" in Africa. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000.

- Tamale, Sylvia. African Sexualities: A Reader. Fahamu/Pambazuka, 2011.

Further reading

Resources

- FORWARD, The Foundation for Women's Health, Research and Development, accessed 9 September 2011.

- "Hospitals and Clinics in the UK offering Specialist FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) Services", FORWARD, accessed 7 September 2011.

Books

- Abdalla, Raqiya Haji Dualeh. Sisters in Affliction: Circumcision and Infibulation of Women in Africa. Zed Books, 1982.

- Aldeeb, Sami. Male & female circumcision: Among Jews, Christians and Muslims. Shangri-La Publications, 2001.

- Dorkenoo, Efua. Cutting the rose: Female genital mutilation. Minority Rights Publications, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, 1996.

- Sanderson, Lilian Passmore. Against the Mutilation of Women. Ithaca Press, 1981.

- Skaine, Rosemarie. Female Genital Mutilation. McFarland & Company, 2005.

Background reading

- Dettwyler, Katherine A. Dancing Skeletons: Life and Death in West Africa. Waveland Press, 1994.

- Mernissi, Fatima. Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in a Modern Muslim Society. Indiana University Press, 1987 [first published 1975].

Articles

- Abusharaf, R. M. (2001). "Virtuous Cuts: Female Genital Circumcision in an African Ontology". Differences. 12: 112–40. doi:10.1215/10407391-12-1-112.

- Althaus, F. A. (1997). "Female Circumcision: Rite of Passage or Violation of Rights?". International Family Planning Perspectives. 23 (3): 130–3. doi:10.2307/2950769. JSTOR 2950769.

- Boddy, J. (1982). "Womb as Oasis: The Symbolic Context of Pharaonic Circumcision in Rural Northern Sudan". American Ethnologist. 9 (4): 682–698. doi:10.1525/ae.1982.9.4.02a00040. JSTOR 644690.

- Chase, Cheryl (2002). "'Cultural practice' or 'Reconstructive Surgery'? U.S. Genital Cutting, the Intersex Movement, and Medical Double Standards". In James, Stanlie M.; Robertson, Claire C. (eds.). Genital Cutting and Transnational Sisterhood. University of Illinois Press. pp. 126–51. ISBN 978-0-252-02741-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Ehrenreich, Nancy; Barr, Mark (2005). "Intersex Surgery, Female Genital Cutting, and the Selective Condemnation of 'Cultural Practices'" (PDF). Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 40 (1): 71–140.

- Ferguson, Ian and Ellis, Pamela. "Female Genital Mutilation: a Review of the Current Literature", Research Section, Department of Justice, Canada, 1995, accessed 9 September 2011.

- Oguntoye, Susana; Otoo-Oyortey, Naana; Hemmings, Joanne; Norman, Kate; Hussein, Eiman (2009). "'FGM is with us Everyday': Women and Girls Speak Out about Female Genital Mutilation in the UK" (PDF). World Academy of Science and Engineering. 54: 1020–5.

- Population Reference Bureau. "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Data and Trends", 2008, accessed 7 September 2011.

- Shell-Duncan, Bettina (2001). "The medicalization of female 'circumcision': Harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice?" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 52 (7): 1013–28. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00208-2.

- UNICEF Template:Fr icon. Evaluation of Senegal's "National Action Plan for the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation", accessed 7 September 2011.

- UNICEF. "Coordinated Strategy to Abandon Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in One Generation", accessed 7 September 2011.

- Darugar, Maliha A; Harris, Rebecca M; and Frader, Joel E. "Consent and cultural conflicts: ethical issues in pediatric anesthesiologists' participation in female genital cutting", in Van Norman, Gail A; Jackson, Stephen; and Rosenbaum, Stanley H. Clinical Ethics in Anesthesiology: A Case-Based Textbook. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Literature and personal stories

- Ali, Ayaan Hirsi. Infidel: My Life. Simon & Schuster, 2007: Ayaan experiences FGM at the hands of her grandmother.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Flower. Harper Perennial, 1999: autobiographical novel about Dirie's childhood and genital mutilation.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Dawn. Little, Brown, 2003: how Dirie became a UN Special Ambassador for FGM.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Children. Virago, 2007: FGM in Europe.

- El Saadawi, Nawal. Woman at Point Zero. Zed Books, 1975.

- Walker, Alice. Possessing the Secret of Joy. New Press, 1993: explores violence, sexism, misogyny, and FGM in African, British, and American society.

- Williams-Garcia, Rita. No Laughter Here. HarperCollins, 2004: about a ten-year-old Nigerian girl who underwent FGM while on vacation in her homeland.

Films

- Brendecke, Dagmar and Müller-Belecke, Anke. Schnitt ins Leben – Afrikanerinnen bekämpfen ein Ritual. Germany, 2000 (documentary).

- Dacosse, Marc and Eric Dagostino, Eric. L’Appel de Diégoune (Walking the Path of Unity). Tostan, France, 2009; link courtesy of Tostan International, YouTube, accessed 13 September 2011.

- Eran, Doron. God's Sandbox. Israel, 2006: An Israeli girl joins a Muslim tribe and is forced to undergo FGM.

- Hormann, Sherry. Desert Flower. 2009: Based on Waris Dirie's book, Desert Flower.

- Johnson, Kirsten and Pimsleur, Julia. Bintou in Paris. France, 1995 (documentary).

- Kouros, Alex. Kokonainen. Finland, 2005: won the 2005 New York Short Film Festival Jury Award for Best Screenplay.

- Longinotto, Kim. The Day I Will Never Forget. UK, 2002.

- Maldonado, Fabiola. Maimouna – La vie devant moi. Germany, 2007 (documentary).

- Pomerance, Erica. Dabla! Excision. Canada, 2003: Follows the growing movement across Africa to stop FGM.

- Sembène, Ousmane. Moolaadé. Senegal, France, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Morocco, Tunisia, 2004.

- Sissoko, Cheick Oumar. Finzan. Mali, 1989: Two women rebel against the traditions of a village society.

- Wilkins, Oliver. Short film on FGM in Minya, Egypt, vimeo.com, accessed 7 September 2011.