A Midsummer Night's Dream

A Midsummer Night's Dream is a play that was written by William Shakespeare. It is believed to have been written between 1590 and 1596. It portrays the events surrounding the marriage of the Duke of Athens, Theseus, and the Queen of the Amazons, Hippolyta. These include the adventures of four young Athenian lovers and a group of amateur actors, who are manipulated by the fairies who inhabit the forest in which most of the play is set. The play is one of Shakespeare's most popular works for the stage and is widely performed across the world.

Characters

|

|

Synopsis

The play features three interlocking plots, connected by a celebration of the wedding of Duke Theseus of Athens and the Amazon queen, Hippolyta, and set simultaneously in the woodland, and in the realm of Fairyland, under the light of the moon.[1]

In the opening scene, Hermia refuses to follow her father Egeus's instructions to marry Demetrius, whom he has chosen for her. In response, Egeus quotes before Theseus an ancient Athenian law whereby a daughter must marry the suitor chosen by her father, or else face death. Theseus offers her another choice: lifelong chastity worshiping the goddess Diana as a nun.

At that same time, Quince and his fellow players were engaged to produce an act which is "the most lamentable comedy and most cruel death of Pyramus and Thisbe", for the Duke and the Duchess.[2] Peter Quince reads the names of characters and bestows them to the players. Nick Bottom who is playing the main role of Pyramus, is over-enthusiastic and wants to dominate others by suggesting himself for the characters of Thisbe, The Lion and Pyramus at the same time. Also he would rather be a tyrant and recites some lines of Ercles or Hercules. Quince ends the meeting with "at the Duke's oak we meet".

Meanwhile, Oberon, king of the fairies, and his queen, Titania, have come to the forest outside Athens. Titania tells Oberon that she plans to stay there until after she has attended Theseus and Hippolyta's wedding. Oberon and Titania are estranged because Titania refuses to give her Indian changeling to Oberon for use as his "knight" or "henchman," since the child's mother was one of Titania's worshipers. Oberon seeks to punish Titania's disobedience, so he calls for his mischievous court jester Puck or "Robin Goodfellow" to help him apply a magical juice from a flower called "love-in-idleness," which when applied to a person's eyelids while sleeping makes the victim fall in love with the first living thing seen upon awakening. He instructs Puck to retrieve the flower so that he can make Titania fall in love with the first thing she sees when waking from sleep, which he is sure will be an animal of the forest. Oberon's intent is to shame Titania into giving up the little Indian boy. He says, "And ere I take this charm from off her sight, / As I can take it with another herb, / I'll make her render up her page to me."[3]

Having seen Demetrius act cruelly toward Helena, Oberon orders Puck to spread some of the magical juice from the flower on the eyelids of the young Athenian man. Instead, Puck mistakes Lysander for Demetrius, not having actually seen either before. Helena, coming across him, wakes him while attempting to determine whether he is dead or asleep. Upon this happening, Lysander immediately falls in love with Helena. Oberon sees Demetrius still following Hermia and is enraged. When Demetrius decides to go to sleep, Oberon sends Puck to get Helena while he charms Demetrius' eyes. Upon waking up, he sees Helena. Now, both men are in pursuit of Helena. However, she is convinced that her two suitors are mocking her, as neither loved her originally. Hermia is at a loss to see why her lover has abandoned her, and accuses Helena of stealing Lysander away from her. The four quarrel with each other until Lysander and Demetrius become so enraged that they seek a place to duel each other to prove whose love for Helena is the greatest. Oberon orders Puck to keep Lysander and Demetrius from catching up with one another and to remove the charm from Lysander, so that he goes back to being in love with Hermia.

Meanwhile, a band of six labourers ("rude mechanicals", as they are described by Puck) have arranged to perform a play about Pyramus and Thisbe for Theseus' wedding and venture into the forest, near Titania's bower, for their rehearsal. Nick Bottom, a stage-struck weaver, is spotted by Puck, who (taking his name to be another word for a jackass) transforms his head into that of a donkey. When Bottom returns for his next lines, the other workmen run screaming in terror. Determined to wait for his friends, he begins to sing to himself. Titania is awakened by Bottom's singing and immediately falls in love with him. She lavishes him with attention, and presumably makes love to him. While she is in this state of devotion, Oberon takes the changeling. Having achieved his goals, Oberon releases Titania, orders Puck to remove the donkey's head from Bottom, and arrange everything so that Hermia, Lysander, Demetrius, and Helena will believe that they have been dreaming when they awaken. The magical enchantment is removed from Lysander, leaving Demetrius under the spell and in love with Helena.

The fairies then disappear, and Theseus and Hippolyta arrive on the scene, during an early morning hunt. They wake the lovers and, since Demetrius does not love Hermia any more, Theseus overrules Egeus's demands and arranges a group wedding. The lovers decide that the night's events must have been a dream. After they all exit, Bottom awakes, and he too decides that he must have experienced a dream "past the wit of man". In Athens, Theseus, Hippolyta and the lovers watch the six workmen perform Pyramus and Thisbe. The play is badly performed to the point where the guests laugh as if it were meant to be a comedy, and afterward everyone retires to bed. Afterward, Oberon, Titania, Puck, and other fairies enter, and bless the house and its occupants with good fortune. After all other characters leave, Puck "restores amends" and reminds the audience that this might be nothing but a dream (hence the name of the play).

Sources and date

It is unknown exactly when A Midsummer Night's Dream was written or first performed, but on the basis of topical references and an allusion to Edmund Spenser's 'Epithalamion', it is usually dated 1594 or 1596. Some have theorised that the play might have been written for an aristocratic wedding (for example that of Elizabeth Carey, Lady Berkeley), while others suggest that it was written for the Queen to celebrate the feast day of St. John. No concrete evidence exists to support either theory. In any case, it would have been performed at The Theatre and, later, The Globe. Though it is not a translation or adaptation of an earlier work, various sources such as Ovid's Metamorphoses and Chaucer's "The Knight's Tale" served as inspiration.[4]

Publication and text

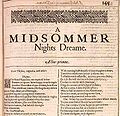

The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 8 October 1600 by the bookseller Thomas Fisher, who published the first quarto edition later that year. A second quarto was printed in 1619 by William Jaggard, as part of his so-called False Folio.[5] The play next appeared in print in the First Folio of 1623. The title page of Q1 states that the play was "sundry times publickely acted" prior to 1600. The first performance known with certainty occurred at Court on 1 January 1605.

Performance history

17th and 18th centuries

During the years of the Puritan Interregnum when the theatres were closed (1642–60), the comic subplot of Bottom and his compatriots was performed as a "droll". Drolls were comical playlets, often adapted from the subplots of Shakespearean and other plays, that could be attached to the acts of acrobats and jugglers and other allowed performances, thus circumventing the ban against drama.

When the theatres re-opened in 1660, A Midsummer Night's Dream was acted in adapted form, like many other Shakespearean plays. Samuel Pepys saw it on 29 September 1662 and thought it "the most insipid, ridiculous play that ever I saw ..."[6]

After the Jacobean/Caroline era, A Midsummer Night's Dream was never performed in its entirety until the 1840s. Instead, it was heavily adapted in forms like Henry Purcell's musical masque/play The Fairy Queen (1692), which had a successful run at the Dorset Garden Theatre, but was not revived. Richard Leveridge turned the Pyramus and Thisbe scenes into an Italian opera burlesque, acted at Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1716. John Frederick Lampe elaborated upon Leveridge's version in 1745. Charles Johnson had used the Pyramus and Thisbe material in the finale of Love in a Forest, his 1723 adaptation of As You Like It. In 1755, David Garrick did the opposite of what had been done a century earlier: he extracted Bottom and his companions and acted the rest, in an adaptation called The Fairies. Frederic Reynolds produced an operatic version in 1816.[7]

The Victorian stage

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

In 1840, Madame Vestris at Covent Garden returned the play to the stage with a relatively full text, adding musical sequences and balletic dances. Vestris took the role of Oberon, and for the next seventy years, Oberon and Puck would always be played by women. After the success of Vestris' production, 19th-century theatre continued to stage the Dream as a spectacle, often with a cast numbering nearly one hundred. Detailed sets were created for the palace and the forest, and the fairies were portrayed as gossamer-winged ballerinas. The overture by Felix Mendelssohn was always used throughout this period. Augustin Daly's production opened in 1895 in London and ran for 21 performances. The special effects were constructed by the Martinka Magic Company, which was later owned by Houdini.

Twentieth century

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

Herbert Beerbohm Tree staged a 1911 production with live rabbits.

Max Reinhardt staged A Midsummer Night's Dream thirteen times between 1905 and 1934, introducing a revolving set. After he fled Germany he devised a more spectacular outdoor version at the Hollywood Bowl, in September 1934. The shell was removed and replaced by a forest planted in tons of dirt hauled in especially for the event, and a trestle was constructed from the hills to the stage. The wedding procession inserted between Acts IV and V crossed the trestle with torches down the hillside. The cast included John Davis Lodge, William Farnum, Sterling Holloway, Olivia de Havilland, Mickey Rooney and a corps of dancers which included Katherine Dunham and Butterfly McQueen, with Mendelssohn's music.

On the strength of this production, Warner Brothers signed Reinhardt to direct a filmed version, Hollywood's first Shakespeare movie since Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and Mary Pickford's Taming of the Shrew in 1929. Rooney (Puck) and De Havilland (Hermia) were the only holdovers from the Hollywood Bowl cast. James Cagney starred, in his only Shakespearean role, as Bottom. Other actors in the film who played Shakespearean roles just this once included Joe E. Brown and Dick Powell. Erich Wolfgang Korngold was brought from Austria to arrange Mendelssohn's music for the film. He not only used the Midsummer Night's Dream music but also several other pieces by Mendelssohn. Korngold went on to make a Hollywood career, remaining in the U.S. after the Nazis invaded Austria.

Director Harley Granville-Barker introduced in 1914 a less spectacular way of staging the Dream: he reduced the size of the cast and used Elizabethan folk music instead of Mendelssohn. He replaced large, complex sets with a simple system of patterned curtains. He portrayed the fairies as golden robotic insectoid creatures based on Cambodian idols. His simpler, sparer staging significantly influenced subsequent productions.

In 1970, Peter Brook staged the play for the Royal Shakespeare Company in a blank white box, in which masculine fairies engaged in circus tricks such as trapeze artistry. Brook also introduced the subsequently popular idea of doubling Theseus/Oberon and Hippolyta/Titania, as if to suggest that the world of the fairies is a mirror version of the world of the mortals. British actors who played various roles in Brook's production included Patrick Stewart, Ben Kingsley, John Kane (Puck) and Jennie Stoller (Helena).

Since Brook's production, directors have used their imaginations freely in staging the play. In particular, there has been an increased use of sexuality on stage, as many directors see the palace as a symbol of restraint and repression, while the wood is a symbol of unrestrained sexuality, both liberating and terrifying.

A Midsummer Night's Dream has been produced many times in New York, including several stagings by the New York Shakespeare Festival at the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park and a production by the Theatre for a New Audience, produced by Joseph Papp at the Public Theatre. In 1978, the Riverside Shakespeare Company staged an outdoor production starring Eric Hoffmann as Puck, with Karen Hurley as Titania and Eric Conger as Oberon, directed by company founder Gloria Skurski. There have been several variations since then, including some set in the 1980s.

Analysis and criticism

Themes in the story

Love

David Bevington argues that the play represents the dark side of love. He writes that the fairies make light of love by mistaking the lovers and by applying a love potion to Titania's eyes, forcing her to fall in love with an ass.[8] In the forest, both couples are beset by problems. Hermia and Lysander are both met by Puck, who provides some comic relief in the play by confounding the four lovers in the forest. However, the play also alludes to serious themes. At the end of the play, Hermia and Lysander, happily married, watch the play about the unfortunate lovers, Pyramus and Thisbe, and are able to enjoy and laugh at it.[9] Helena and Demetrius are both oblivious to the dark side of their love, totally unaware of what may have come of the events in the forest.

Problem with time

There is a dispute over the scenario of the play as it is cited at first by Theseus that "four happy days bring in another moon",[2] the wood episode then takes place at a night of no moon, but Lysander asserts that there will be so much light in the very night they will escape that dew on the grass will be shining[10] like liquid pearls. Also, in the next scene Quince states that they will rehearse in moonlight[11] which creates a real confusion. It is possible that the Moon set during the night allowing Lysander to escape in the moonlight and for the actors to rehearse, then for the wood episode to occur without moonlight. Theseus's statement can mean four days until the next month.

Loss of individual identity

Maurice Hunt, Chair of the English Department at Baylor University, writes of the blurring of the identities of fantasy and reality in the play that make possible "that pleasing, narcotic dreaminess associated with the fairies of the play".[12] By emphasising this theme even in the setting of the play, Shakespeare prepares the reader's mind to accept the fantastic reality of the fairy world and its magical happenings. This also seems to be the axis around which the plot conflicts in the play occur. Hunt suggests that it is the breaking down of individual identities that leads to the central conflict in the story.[12] It is the brawl between Oberon and Titania, based on a lack of recognition for the other in the relationship, that drives the rest of the drama in the story and makes it dangerous for any of the other lovers to come together due to the disturbance of Nature caused by a fairy dispute.[12] Similarly, this failure to identify and make distinction is what leads Puck to mistake one set of lovers for another in the forest and place the juice of the flower on Lysander's eyes instead of Demetrius'.

Victor Kiernan, a Marxist scholar and historian, writes that it is for the greater sake of love that this loss of identity takes place and that individual characters are made to suffer accordingly: "It was the more extravagant cult of love that struck sensible people as irrational, and likely to have dubious effects on its acolytes".[13] He believes that identities in the play are not so much lost as they are blended together to create a type of haze through which distinction becomes nearly impossible. It is driven by a desire for new and more practical ties between characters as a means of coping with the strange world within the forest, even in relationships as diverse and seemingly unrealistic as the brief love between Titania and Bottom the Ass: "It was the tidal force of this social need that lent energy to relationships".[14]

David Marshall, an aesthetics scholar and English Professor at the University of California – Santa Barbara, takes this theme to an even further conclusion, [citation needed] pointing out that the loss of identity is especially played out in the description of the mechanicals their assumption of other identities. In describing the occupations of the acting troupe, he writes "Two construct or put together, two mend and repair, one weaves and one sews. All join together what is apart or mend what has been rent, broken, or sundered". In Marshall's opinion, this loss of individual identity not only blurs specificities, it creates new identities found in community, which Marshall points out may lead to some understanding of Shakespeare's opinions on love and marriage. Further, the mechanicals understand this theme as they take on their individual parts for a corporate performance of Pyramus and Thisbe. Marshall remarks that "To be an actor is to double and divide oneself, to discover oneself in two parts: both oneself and not oneself, both the part and not the part". He claims that the mechanicals understand this and that each character, particularly among the lovers, has a sense of laying down individual identity for the greater benefit of the group or pairing. It seems that a desire to lose one's individuality and find identity in the love of another is what quietly moves the events of A Midsummer Night's Dream. It is the primary sense of motivation and is even reflected in the scenery and mood of the story.

Ambiguous sexuality

In his essay "Preposterous Pleasures, Queer Theories and A Midsummer Night's Dream", Douglas E. Green explores possible interpretations of alternative sexuality that he finds within the text of the play, in juxtaposition to the proscribed social mores of the culture at the time the play was written. He writes that his essay "does not (seek to) rewrite A Midsummer Night's Dream as a gay play but rather explores some of its 'homoerotic significations' ... moments of 'queer' disruption and eruption in this Shakespearean comedy".[15] Green states that he does not consider Shakspeare to have been a "sexual radical", but that the play represented a "topsy-turvy world" or "temporary holiday" that mediates or negotiates the "discontents of civilisation", which while resolved neatly in the story's conclusion, do not resolve so neatly in real life.[16] Green writes that the "sodomitical elements", "homoeroticism", "lesbianism", and even "compulsory heterosexuality" in the story must be considered in the context of the "culture of early modern England" as a commentary on the "aesthetic rigidities of comic form and political ideologies of the prevailing order". Aspects of ambiguous sexuality and gender conflict in the story are also addressed in essays by Shirley Garner[17] and William W.E. Slights[18] albeit all the characters are played by males.

Feminism

Male dominance is one thematic element found in A Midsummer Night's Dream. Shakespeare's comedies often include a section in which females enjoy more power and freedom than they actually possess[citation needed]. In A Midsummer Night's Dream, Lysander and Hermia escape into the woods for a night where they do not fall under the laws of Theseus or Egeus. Upon their arrival in Athens, the couples are married. Marriage is seen as the ultimate social achievement for women while men can go on to do many other great things and gain societal recognition.[19] In his article, "The Imperial Votaress", Louis Montrose draws attention to male and female gender roles and norms present in the comedy in connection with Elizabethan culture. In reference to the triple wedding, he says, "The festive conclusion in A Midsummer Night's Dream depends upon the success of a process by which the feminine pride and power manifested in Amazon warriors, possessive mothers, unruly wives, and wilful daughters are brought under the control of lords and husbands."[20] He says that the consummation of marriage is how power over a woman changes hands from father to husband. A connection between flowers and sexuality is drawn. The juice employed by Oberon can be seen as symbolising menstrual blood as well as the sexual blood shed by virgins. While blood as a result of menstruation is representative of a woman's power, blood as a result of a first sexual encounter represents man's power over women.[21]

There are points in the play, however, when there is an absence of patriarchal control. In his book, Power on Display, Leonard Tennenhouse says the problem in A Midsummer Night's Dream is the problem of "authority gone archaic".[22] The Athenian law requiring a daughter to die if she does not do her father's will is outdated. Tennenhouse contrasts the patriarchal rule of Theseus in Athens with that of Oberon in the carnivalistic Faerie world. The disorder in the land of the faeries completely opposes the world of Athens. He states that during times of carnival and festival, male power is broken down. For example, what happens to the four lovers in the woods as well as Bottom's dream represents chaos that contrasts with Theseus' political order. However, Theseus does not punish the lovers for their disobedience. According to Tennenhouse, by forgiving of the lovers, he has made a distinction between the law of the patriarch (Egeus) and that of the monarch (Theseus), creating two different voices of authority. This distinction can be compared to the time of Elizabeth I in which monarchs were seen as having two bodies: the body natural and the body mystical. Elizabeth's succession itself represented both the voice of a patriarch as well as the voice of a monarch: (1) her father's will which stated that the crown should pass to her and (2) the fact that she was the daughter of a king.[23] The challenge to patriarchal rule in A Midsummer Night's Dream mirrors exactly what was occurring in the age of Elizabeth I.

Adaptations and cultural references

Literary

Botho Strauß' play Der Park (1983) is based on characters and motifs from A Midsummer Night's Dream. Similarly, motifs and structures from the Dream are used in The Morning After Optimism (1971) by Tom Murphy[24] and A Bucket of Eels (1994) by Paul Godfrey.[25] St. John's Eve written in 1853 by Henrik Ibsen relies heavily on the Shakespearean play. The Thyme of the Season, written in 2006 by Duncan Pflaster is a sequel to Shakespeare's play, set on Halloween. Terry Pratchett's 1992 novel Lords and Ladies features a wedding, an estranged King and Queen of some mythic note and a band of rude mechanicals putting on a play.

In Angela Carter's last novel, Wise Children, the character Genghis Khan directs a film production of A Midsummer Night's Dream in Hollywood with his first wife Daisy Duck as Titania and main characters, Dora and Nora Chance, as Peaseblossom and Mustardseed.

For his series The Sandman, Neil Gaiman included a fantastical retelling of the play's origins in the graphic novel Dream Country. It won several awards, and is distinguished by being the only comic that has ever won a World Fantasy Award.

In 2006–2007, comic-strip artist Brooke McEldowney, creator of 9 Chickweed Lane and the webcomic Pibgorn, adapted the story into a 20th century setting in Pibgorn, using characters from both his comic series in the "cast".

A Midwinter Morning's Tale is comic of the Corto Maltese series by Hugo Pratt. Oberon, Puck, Morgan Le Fey and Merlin appear in the comic as a representation of the Gaelic and Celtic fantasy beings. They choose Corto Maltese as their knight to fight for their sake against a possible German invasion in the context of World War I.

Jean Betts of New Zealand also adapted the play to make a comedic feminist spoof, "Revenge of the Amazons" (1996). The gender-roles are reversed (play actors are feminist "thesbians"/ Oberon falls in love with a "bunny girl"). It is set in the 1970s with many social references and satire.

Magic Street (2005) by Orson Scott Card revisits the work as a continuation of the play under the premise that the story by Shakespeare was actually derived from true interactions with fairy folk.

A Midsummer Night's Gene (1997) by Andrew Harman is a sci-fi parody of Shakespeare's play.

Faerie Tale, the 1988 fantasy novel by Raymond E. Feist, contains many references to the characters represented in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

The Sisters Grimm series written by Micheal Buckley, features Puck, the Trickster King, as one of the main characters. In the fourth book of the series, Once Upon a Crime, Titania, Oberon, and other Faerie Folk are introduced.

The teen book This Must Be Love (2004) by Tui Sutherland is based on the play. The characters have similar or identical names to the original. One sub-plot involves a school play of another Shakespearean play, Romeo and Juliet, and another sub-plot involves the main characters going to see a play entitled "The Fairies Quarrel" in which a character acts like Puck amongst the main characters.

In Leslie Livingston's series for young adults, Wondrous Strange, 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' is shown as a realm.

Musical versions

Henry Purcell

The Fairy-Queen by Henry Purcell consists of a set of masques meant to go between acts of the play, as well as some minimal rewriting of the play to be current to 17th century audiences.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

In 1826, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy composed an overture for concert performance, inspired by the play. It was first performed in 1827. In 1842, partly because of the fame of the overture, and partly because his employer King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia liked the incidental music that Mendelssohn had written for other plays that had been staged at the palace in German translation, Mendelssohn was commissioned to write incidental music for a production of A Midsummer Night's Dream to be staged in 1843 in Potsdam. He incorporated the existing Overture into the incidental music, which was used in most stage versions through the 19th century. Among the pieces in the incidental music is his Wedding March, used most often today as a recessional in Western weddings.

The choreographer Marius Petipa, more famous for his collaborations with Tchaikovsky (on the ballets Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty) made another ballet adaptation for the Imperial Ballet of St. Petersburg with additional music and adaptations to Mendelssohn's score by Léon Minkus. The revival premiered 14 July 1876. English choreographer Frederick Ashton also created a 40-minute ballet version of the play, retitled to The Dream. George Balanchine was another to create a Midsummer Night's Dream ballet based on the play, using Mendelssohn's music.

Between 1917 and 1939 Carl Orff also wrote incidental music for a German version of the play, Ein Sommernachtstraum (performed in 1939). Since Mendelssohn's parents were Jews who converted to Lutheranism, his music had been banned by the Nazi regime, and the Nazi cultural officials put out a call for new music for the play: Orff was one of the musicians who responded. He later reworked the music for a final version, completed in 1964.

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Over Hill, Over Dale, from Act 2, is the third of the Three Shakespeare Songs set to music by the British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He wrote the pieces for a cappella SATB choir in 1951 for the British Federation of Music Festivals, and they remain a popular part of British choral repertoire today.

Benjamin Britten

The play was adapted into an opera, with music by Benjamin Britten and libretto by Britten and Peter Pears. The opera was first performed on 1 June 1960 at Aldeburgh.

Moonwork

The theatre company, Moonwork put on a production of Midsummer in 1999. It was conceived by Mason Pettit, Gregory Sherman and Gregory Wolfe (who directed it). The show featured a rock-opera version of the play within a play, Pyramus & Thisbe with music written by Rusty Magee. The music for the rest of the show was written by Andrew Sherman.

The Donkey Show

The Donkey Show is a disco-era experience based on A Midsummer Night's Dream, that first appeared Off-Broadway in 1999.[26]

Other

In 1949 a three-act opera by Delannoy entitled Puck was premiered in Strasbourg.

Progressive Rock guitarist Steve Hackett, best known for his work with Genesis, made a classical adaptation of the play in 1997.

Hans Werner Henze's Eighth Symphony is inspired by sequences from the play.

Ballets

- George Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream, his first original full-length ballet, was premiered by the New York City Ballet on 17 January 1962. It was chosen to open the NYCB's first season at the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center in 1964. Balanchine interpolated further music by Mendelssohn into his Dream, including the overture from Athalie.[27][28][29][30] A film version of the ballet was released in 1966.[citation needed]

- Frederick Ashton created his "The Dream", a short (not full-length) ballet set exclusively to the famous music by Félix Mendelssohn, arranged by John Lanchbery, in 1964. It was created on England's Royal Ballet and has since entered the repertoire of other companies, notably The Joffrey Ballet and American Ballet Theatre.[30]

- John Neumeier created his full-length ballet Ein Sommernachtstraum for his company at the Hamburg State Opera (Hamburgische Staatsoper) in 1977. Longer than Ashton's or Balanchine's earlier versions, Neumeier's version includes other music by Mendelssohn along with the Midsummer Night's Dream music, as well as music from the modern composer György Sándor Ligeti, and jaunty barrel organ music. Neumeier devotes the three sharply differing musical styles to the three character groups, with the aristocrats and nobles dancing to Mendelssohn, the fairies to Ligeti, and the rustics or mechanicals to the barrel organ.[31] Neumeier set his A Midsummer Night's Dream for the Bolshoi Ballet in 2005.[32]

- Elvis Costello composed the music for a full-length ballet Il Sogno, based on A Midsummer Night's Dream. The music was subsequently released as a classical album by Deutsche Grammophon in 2004.

Film adaptations

A Midsummer Night's Dream has been adapted as a film several times. The following are the best known.

- A 1935 film version[33] was directed by Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle, produced by Henry Blanke and adapted by Charles Kenyon and Mary C. McCall Jr. The cast included James Cagney as Bottom, Mickey Rooney as Puck, Olivia de Havilland as Hermia, Joe E. Brown as Francis Flute, Dick Powell as Lysander and Victor Jory as Oberon. Many of the actors in this version had never performed Shakespeare and never would do so again, notably Cagney and Brown, who were nevertheless highly acclaimed for their performances in the film.[34]

- A 1968 film version[35] was directed by Peter Hall. The cast included Paul Rogers as Bottom, Ian Holm as Puck, Diana Rigg as Helena, Helen Mirren as Hermia, Ian Richardson as Oberon, Judi Dench as Titania, and Sebastian Shaw as Quince. This film stars the Royal Shakespeare Company, and is directed by Peter Hall. It is sometimes confused with Peter Brook's highly successful 1971 production, but the two are different, and Brook's production was never filmed. The fairies in Peter Hall's production wore green body paint. It received its U.S. premiere on CBS as a television special in early 1969.

- A Midsummer Night's dream/Sen noci svatojánské (1969) was director by Czech animator Jiri Trnka. This was stop-motion puppet film that followed Shakespeare's story simply with a narrator.

- A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy (1982) was a film written and directed by Woody Allen. The plot is loosely based on Ingmar Bergman's Smiles of a Summer Night, with some elements from Shakespeare's play.

- A 1996 adaptation[36] directed by Adrian Noble. The cast included Desmond Barrit as Bottom, Barry Lynch as Puck, Alex Jennings as Oberon/Theseus, and Lindsay Duncan as Titania/Hippolyta. This film is based on Noble's hugely popular Royal Shakespeare Company production. Its art design is eccentric, featuring a forest of floating light bulbs and a giant umbrella for Titania's bower.

- A 1999 film version[37] was written and directed by Michael Hoffman. The cast included Kevin Kline as Bottom, Rupert Everett as Oberon, Michelle Pfeiffer as Titania, Stanley Tucci as Puck, Sophie Marceau as Hippolyta, Christian Bale as Demetrius, Dominic West as Lysander and Calista Flockhart as Helena. This adaptation relocates the play's action from Athens to a fictional Monte Athena, located in the Tuscany, although all textual mentions of Athens were retained.

- A 1999 version[38] was written and directed by James Kerwin. The cast included Travis Schuldt as Demetrius. It set the story against a surreal backdrop of techno clubs and ancient symbols.

- A Midsummer Night's Rave (2002)[39] directed by Gil Cates Jr. changes the setting to a modern rave. Puck is a drug dealer, the magic flower called love-in-idleness is replaced with magic ecstasy, and the King and Queen of Fairies are the host of the rave and the DJ. Other differences include changing the character names such as 'Lysander' becoming 'Xander'.

TV productions

- The 1981 BBC Television Shakespeare production was produced by Jonathan Miller. It starred Helen Mirren as Titania, Peter McEnery as Oberon, Robert Lindsay as Lysander, Geoffrey Palmer as Quince and Brian Glover as Bottom.

- In 2005 ShakespeaRe-Told, the BBC TV series, aired an updated of the play. It was written by Peter Bowker. The cast includes Johnny Vegas as Bottom, Dean Lennox Kelly as Puck, Bill Paterson as Theo (a conflation of Theseus and Egeus), and Imelda Staunton as his wife Polly (Hippolyta). Lennie James plays Oberon and Sharon Small is Titania. Zoe Tapper and Michelle Bonnard play Hermia and Helena.

Film and television references

This article may contain minor, trivial or unrelated fictional references. |

Rehearsals for a performance of the play by American servicemen stationed in Kent during WW2 appear in the 1946 Powell and Pressburger film A Matter of Life and Death.

Porky's II: The Next Day: The entire high school class presents a Shakespeare festival, which the local redneck religious leaders hypocritically shut down on the grounds of indecency (they are later revealed to have been involved in scandalous behaviour themselves). One of the plays presented in the festival is A Midsummer Night's Dream, which the local preacher frowns on for having such lines as Theseus's " 'Tis almost fairy time".

Dead Poets Society: The tragic protagonist of the movie Dead Poets Society, Neil Perry (Robert Sean Leonard), was cast as Puck in a local production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. Only a few frames of his performance are seen, including the ending monologue which could be interpreted as a literary device used by the writer (Tom Schulman) to emphasise his unsuccessful plea to his father.

Disney's animated series Gargoyles featured many characters from Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream, including Oberon, Titania, and, most prominently, Puck. In this series, Puck actually takes the form of Owen, loyal assistant to the main villain Xanatos. Later, Puck becomes the tutor for Xanatos' quarter-fae son, Alex. He is wily, sprightly, and willing to have fun at the expense of others.

Get Over It: The 2001 film stars Kirsten Dunst (Kelly Woods/Helena), Ben Foster (Berke Landers/Lysander), Melissa Sagemiller (Allison McAllister/Hermia) and Shane West (Bentley 'Striker' Scrumfeld/Demetrius) in a "teen adaptation" of Shakespeare's play. The characters are set in high school, and in addition to some similarities in plot, there is a sub-plot involving the main characters acting in a musical production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Were the World Mine, a 2008 musical independent film, involves a gay student cast in the role of Puck in his high school's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. The plot revolves around the boy actually making the love-in-idleness potion and turning his crush, classmates and other residents of his town temporarily gay.

Astronomy

British Astronomer William Herschel named the two moons of Uranus he discovered in 1787 after characters in the play, Oberon and Titania.

Gallery

-

First folio, 1623

-

Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing. William Blake, c.1786

-

"Puck" by Joshua Reynolds, 1789

-

Johann Heinrich Füssli: "Das Erwachen der Elfenkönigin Titania", 1775–1790

-

Johann Heinrich Füssli: Titania liebkost den eselköpfigen Bottom, 1793–94

-

Joseph Noel Paton: "The Reconciliation of Titania and Oberon", 1847

-

Sir Edwin Landseer: Scene From A Midsummer Night's Dream, Titania and Bottom (1848)

-

Puck and the Fairies from William Shakespeare: "The Works of Shakspere, with notes by Charles Knight" (1873)

-

Henry Meynell Rheam: Titania welcoming her fairy brethern

-

Emil Orlik: Actor Hans Wassmann as Nick Bottom in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, 1909.

-

Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream by Arie Teeuwisse, Diever, 1971

-

Performance Saratov Puppet Theatre "Teremok" A Midsummer Night's Dream based on the play by William Shakespeare (2007)

References

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1979). Harold F. Brooks (ed.). The Arden Shakespeare "A Midsummer Nights Dream". Methuen & Co. Ltd. cxxv. ISBN 0-415-02699-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ a b |a midsummer night's dream| editor=R. A. Foakes | Cambridge University Press

- ^ A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act 2, Scene 1, Lines 183–185.

- ^ A Midsummer Night's Dream by Rev. John Hunter ; London; Longmans, Green and CO.;1870

- ^ S4Ulanguages.Com See title page of facsimile of this edition, claiming James Roberts as a publisher and 1600 as the publishing date)

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 142–3 and 316–17.

- ^ Halliday, pp. 255, 271, 278, 316–17, 410.

- ^ Bevington 24–35.

- ^ Bevington 32

- ^ |a midsummer night's dream(I.I.209-213)| editor=R. A. Foakes | Cambridge University Press

- ^ |a midsummer night's dream(I.II.81)| editor=R. A. Foakes | Cambridge University Press

- ^ a b c (Hunt 1)

- ^ (Kiernan 212)

- ^ (Kiernan 210)

- ^ (Green 370)

- ^ (Green 375)

- ^ (Garner 129–130)

- ^ (Slights 261)

- ^ (Howard 414)

- ^ (Montrose 65)

- ^ (Montrose 61–69)

- ^ (Tennenhouse 73)

- ^ (Tennenhouse 74–76)

- ^ "Hot Morning After". Yaleherald.com. 2 November 2001. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Cf. Godfrey's entry in The Continuum Companion to Twentieth Century Theatre

- ^ Internet Off-Broadway Database

- ^ NYCB website

- ^ Balanchine Trust website

- ^ Balanchine Foundation website

- ^ a b Balletmet.org

- ^ Ballet.co.uk

- ^ Biography of John Neumeier on Hamburg Ballet website

- ^ IMDb.com

- ^ Eckert, Charles W., ed. Focus on Shakespearean Films, p. 48 Watts, Richard W. "Films of a Moonstruck World"

- ^ IMDb.com

- ^ IMDB.com

- ^ IMDb.com

- ^ IMDB.com

- ^ IMDB.com

Bibliography

- Bevington, David. "'But We Are Spirits of Another Sort': The Dark Side of Love and Magic in A Midsummer Night's Dream". A Midsummer Night's Dream. Ed. Richard Dutton. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996. 24–35.

- Buchanan, Judith. 2005. Shakespeare on Film. Harlow: Pearson. ISBN 0-582-43716-4. Ch. 5, pp. 121–149.

- Croce, Benedetto. "Comedy of Love". A Midsummer Night's Dream. Eds. Judith M. Kennedy and Richard F. Kennedy. London: Athlone Press, 1999. 386–8.

- Garner, Shirley Nelson. "Jack Shall Have Jill;/ Nought Shall Go Ill". A Midsummer Night's Dream Critical Essays. Ed. Dorothea Kehler. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1998. 127–144. ISBN 0-8153-2009-4

- Green, Douglas E. "Preposterous Pleasures: Queer Theories and A Midsummer Night's Dream". A Midsummer Night's Dream Critical Essays. Ed. Dorothea Kehler. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1998. 369–400. ISBN 0-8153-2009-4

- Howard, Jean E. "Feminist Criticism". Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Eds. Stanley Wells and Lena Cowen Orlin, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. 411–423.

- Huke, Ivan and Perkins, Derek. A Midsummer Night's Dream: Literature Revision Notes and Examples. Celtic Revision Aids. 1981. ISBN 0-17-751305-5.

- Hunt, Maurice. "Individuation in A Midsummer Night's Dream". South Central Review 3.2 (Summer 1986): 1–13.

- Kiernan, Victor. Shakespeare, Poet and Citizen. London: Verso, 1993. ISBN 0-86091-392-9

- Montrose, Louis. "The Imperial Votaress". A Shakespeare Reader: Sources and Criticism. Eds. Richard Danson Brown and David Johnson. London: Macmillan Press, Ltd, 2000. 60–71.

- Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night's Dream. The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans and J.J.M. Tobin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. 256–283. ISBN 0-395-85822-4

- Slights, William W. E. "The Changeling in A Dream". Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900. Rice University Press, 1998. 259–272.

- Tennenhouse, Leonard. Power on Display: the Politics of Shakespeare's Genres. New York: Methuen, Inc., 1986. 73–76. ISBN 0-415-35315-7

External links

- A Midsummer Night's Dream Navigator Annotated, searchable HTML text, with line numbers and scene summaries.

- A Midsummer Night's Dream HTML version of the play.

- No Fear Shakespeare parallel edition: original language alongside a modern translation.

- Video of a Harvard-Radcliffe Summer Theatre Production of the entire play with incidental music by Mendelssohn

- Los Angeles Philharmonic notes

- Notes, including production history