911 (emergency telephone number)

9-1-1 is the emergency telephone number for the North American Numbering Plan (NANP).

It is one of eight N11 codes.

The use of this number is for emergency circumstances only, and to use it for any other purpose (including non-emergency situations and prank calls) can be a crime.[1][2]

History

In the earliest days of telephone technology, prior to the development of the rotary dial telephone, all telephone calls were operator-assisted. To place a call, the caller was required to pick up the telephone receiver and wait for the telephone operator to answer with "Number please?" They would then ask to be connected to the number they wished to call, and the operator would make the required connection manually, by means of a switchboard. In an emergency, the caller might simply say "Get me the police", "I want to report a fire", or "I need an ambulance/doctor". It was usually not necessary to ask for any of these services by number, even in large cities. Indeed, until the ability to dial a phone number came into widespread use in the 1950s (it had existed in limited form since the 1920s), telephone users could not place calls without operator assistance.[3] During the period when an operator was always involved in placing a phone call, the operator instantly knew the calling party's number, even if the caller could not stay on the line, by simply looking at the number above the line jack of the calling party. In smaller centers, telephone operators frequently went the extra mile by making sure they knew the locations of local doctors, vets, law enforcement personnel, and even private citizens who were willing or able to help in an emergency. Frequently, the operator would activate the town's fire alarm, and acted as an informational clearinghouse when an emergency such as a fire occurred. When North American cities and towns began to convert to rotary dial or "automatic" telephone service, many people were concerned about the loss of the personalized service that had been provided by local operators. This problem was partially solved by telling people to dial "0" for the local assistance operator, if they did not know the Fire or Police Department's full number.

In many cases, the local emergency services would attempt to obtain telephone numbers that were easy for the public to remember. Many fire departments, for example, would attempt to obtain an emergency telephone line with a number ending in "3-4-7-3", which spelled the word "Fire" on the corresponding letters of the rotary telephone dial. In some areas (especially during the time when local numbers could be reached by dialing only the last five digits), picking up the phone, dialing one's own local exchange prefix then "F-I-R-E" would ring the nearest fire station.

Some cities made early attempts at a centralized emergency number, using a conventional telephone number. In Toronto, Canada, for example, the Metropolitan Toronto Police communications bureau attempted to promote their emergency number "Empire" 1-1111, or "361-1111", for use in all emergencies (Empire was the name for the exchange "3-6"; all telephone exchanges at the time had corresponding names).[4] The rationale was that the abbreviation of the Empire exchange in common usage, "EM", corresponded to the first two letters of the word "emergency" and that the caller only had to remember the number "1" beyond that. This was never widely accepted, in that the City's fourteen local fire departments continued to tell the public to call them directly and the service never actually included ambulances, which in those days were considered a private transportation service. This was further complicated by the fact that the numbers changed by municipality, and the emergency number and emergency services on one side of a street might be completely different from the other side if the street was a municipal boundary.[5] When a caller was uncertain of his or her exact location, emergency responses could be delayed, and so, for most people, it was simply easier to rely upon the telephone operator to make the connections. The efforts of telephone companies to publicize "Dial '0' for Emergencies" were ultimately abandoned in the face of company staffing and liability concerns,[6] but not before generations of school children were taught to "dial 0 in case of emergency", just as they are currently taught to dial 9-1-1. This situation of unclear emergency telephone numbers would continue, in most places in North America, into the early 1980s. In some locales, the problem persists to this day.

The first known experiment with a national emergency telephone number occurred in the United Kingdom in 1937, using the number 999.[7] The first city in North America to use a central emergency number (in 1959) was the Canadian city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, which instituted the change at the urging of Stephen Juba, mayor of Winnipeg at the time.[8] Winnipeg initially used 999 as the emergency number,[9] but switched numbers when 9-1-1 was proposed by the United States. In the United States, the push for the development of a nationwide American emergency telephone number came in 1957 when the National Association of Fire Chiefs recommended that a single number be used for reporting fires.[10] In 1967, the President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice recommended the creation of a single number that could be used nationwide for reporting emergencies.[11] The burden then fell on the Federal Communications Commission, which then met with AT&T in November, 1967 in order to come up with a solution.

In 1968, a solution was agreed upon. AT&T chose to implement the concept, but with its unique emergency number, 9-1-1, which was brief, easy to remember, dialed easily, and worked well with the phone systems in place at the time. How the number 9-1-1 itself was decided upon is not well known and is subject to much speculation by the general public. However, many assert that the number 9-1-1 was chosen to be similar to the numbers 2-1-1 (long distance), 4-1-1 ("information" or directory assistance), and 6-1-1 (repair service), which had already been in use by AT&T since the 1920s.

Another consideration is that most phones of the time used the pulse dialing system, which could be misdirected if the dial did not spin freely, either from sticky mechanism or a user keeping the finger in the dial. Using 9-1-1 forced the user to remove the dialing finger after the first number (whether using pulse or DTMF dialing) and go to the opposite end of the dial or keypad, thus reducing both accidental failure to dial the number and accidental dialing of the emergency number. Accidental dialing of 9-1-1 has become an increasing problem, as an increasing number of cellular phones are carried in pockets, purses or other places where objects may rest against the keys and repeatedly press them.

Not all such N11 numbers are common throughout the telephone systems of North America. Some of the designated services provided by these numbers are regional, and there are significant differences in number allocation between Canada[12] and the United States;[13] only 4-1-1 and 9-1-1 are universally used. In addition, because it was important to ensure that the emergency number was not dialed accidentally, 9-1-1 made sense because the numbers "9" and "1" were on opposite ends of a phone's rotary dial. Furthermore, the North American Numbering Plan in use at the time established rules for which numbers could be used for area codes and exchanges.[14] At the time, the middle digit of an area code had to be either a 0 or 1, and the first two digits of an exchange could not be a 1.[15] At the telephone switching station, the second dialed digit was used to determine if the number was long distance or local. If the number had a 0 or 1 as the second digit, it was long distance, if it had any other digit, it was a local call. Thus, since the number 9-1-1 was detected by the switching equipment as a special number, it could be routed appropriately. Also, since 9-1-1 was a unique number, never having been used as an area code or service code (although at one point GTE used test numbers such as 11911), it could fit into the existent phone system easily. AT&T announced the selection of 9-1-1 as their choice of the three-digit emergency number at a press conference in the Washington (DC) office of Indiana Rep. J. Edward Roush, who had championed Congressional support of a single emergency number.

Soon after, in Alabama, Bob Gallagher, then-president of the independent Alabama Telephone Company (ATC), read an article in The Wall Street Journal from January 15, 1968, which reported the AT&T 9-1-1 announcement. Gallagher’s competitive spirit motivated him to beat AT&T to the punch by being the first to implement the 9-1-1 service. In need of a suitable spot within his company's territory to implement 9-1-1, he contacted Robert Fitzgerald, who was Inside State Plant Manager for ATC. Fitzgerald recommended Haleyville, Alabama as the prime site. Gallagher later issued a press release announcing that 9-1-1 service would begin in Haleyville on February 16, 1968. Fitzgerald designed the circuitry, and with the assistance of technicians Jimmy White, Glenn Johnston, Al Bush and Pete Gosa, they quickly completed the central office work and installation.[16] Just 35 days after AT&T's announcement, on February 16, 1968, the first-ever 9-1-1 call was placed by Alabama Speaker of the House Rankin Fite, from Haleyville City Hall, to U.S. Rep. Tom Bevill, at the city's police station. Bevill reportedly answered the phone with "Hello". At the City Hall with Fite was Haleyville mayor James Whitt; at the police station with Bevill were Gallagher and Alabama Public Service Commission director Eugene "Bull" Connor. Fitzgerald was at the ATC central office serving Haleyville, and actually observed the call pass through the switching gear as the mechanical equipment clunked out "9-1-1". The phone used to answer the first 9-1-1 call, a bright red model, is now in a museum in Haleyville, while a duplicate phone is still in use at the police station.

In 1968, 9-1-1 became the national emergency number for the United States. In theory at least, calling this single number provided a caller access to police, fire and ambulance services, through what would become known as a common Public-safety answering point (PSAP). The number itself, however, did not become widely known until the 1970s.

Conversion to 9-1-1 in Canada began in 1972 and most major cities are now using 9-1-1. Each year, Canadians make 12 million calls to 9-1-1.[17]

Locating callers automatically

This article appears to contradict the article Enhanced 911. |

In over 98% of locations in the United States and Canada, dialing "911" from any telephone will link the caller to an emergency dispatch center—called a PSAP, or Public Safety Answering Point, by the telecom industry—which can send emergency responders to the caller's location in an emergency. In most areas (approximately 96% of the US) enhanced 911 is available, which automatically gives dispatch the caller's location, if available.[18] Enhanced 9-1-1 or E9-1-1 service is a North American telecommunications-based system that automatically associates a physical address with the calling party's telephone number, and routes the call to the most appropriate Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) for that address. The caller’s address and information (as recorded by the telephone company) are displayed to the PSAP calltaker immediately upon the site's receipt of the call. This provides emergency responders with the location of the emergency without the person calling for help having to provide it. This is often useful in cases of fires, break-ins, kidnapping, and other events where communicating one's location is difficult or impossible. In North America, the system works only if the emergency telephone number 9-1-1 is called. Calls made to other telephone numbers, even though they may be listed as an emergency telephone number, may not permit this feature to function correctly.

Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP)

The final destination of an E9-1-1 call—the location where the 9-1-1 operator is working—is called a Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP). There may be multiple PSAPs within the same exchange, or one PSAP may cover multiple exchanges. The territories covered by a single PSAP are based more on historical and legal police considerations than on telecommunications issues. Most PSAPs have a regional Emergency Service Number, a number identifying the PSAP.

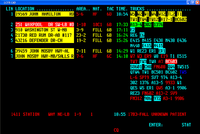

The Caller Location Information (CLI) provided is normally integrated into an emergency dispatch center's computer-assisted dispatch (CAD) system, to provide the dispatcher with an onscreen street map that highlights the caller's position and the nearest available emergency responders. For Wireline (land line) E911, the location is an address. For Wireless E911, the location may be a set of coordinates or the physical address of the cellular tower from which the wireless call originated. Not all PSAPs have the Wireless and Wireline systems integrated. As other aspects of the technology of managing emergency response evolve, the PSAPs will need to evolve with them.[19]

- A system to save lives

-

Typical work station

-

Computerized information processing utilising the AMPDS triage system

-

Public Safety Answering Point

Wireline enhanced 911

In all North American jurisdictions, special privacy legislation permits emergency operators to obtain a 9-1-1 caller's telephone number and location information.[20] This information is gathered by mapping the calling phone number to an address in a database. This database function is known as Automatic Location Identification (ALI).[21] The database is generally maintained by the local telephone company, under a contract with the PSAP. Each telephone company has its own standards for the formatting of the database. Most ALI databases have a companion database known as the MSAG, Master Street Address Guide. The MSAG describes address elements including the exact spellings of street names, and street number ranges.

Each telephone company has at least two redundant telephone trunk lines connecting each host office telephone switch to each PSAP. These trunks are either directly connected to the PSAPs, or are connected to a telephone company central switch that intelligently distributes calls to the PSAPs. These special switches are often known as 9-1-1 Selective Routers.[22] The use of 9-1-1 Selective Routers is becoming increasingly more common, as it simplifies the interconnection between newer office switches and the many older PSAP systems.

The effectiveness of this technology may sometimes be affected by the type of telephone infrastructure that the call is routed through. The PSAP may receive calls from the telephone company on older analog trunks, which are similar to regular telephone lines but are formatted to pass the calling party number. The PSAP may also receive calls on older-style digital trunks, which must be specially formatted to pass Automatic Number Identification (ANI) information only.[23] Some upgraded PSAPs can receive calls in which the calling party number is already present. The location of the call is drawn from a computer routine which supports telephone company service billing, called the Charge Number Parameter. With some technologies, the PSAP trunking does not pass address information along with the call. Instead, only the calling party number is passed, and the PSAP must use the calling party number to look up the address in the ALI database. The ALI database is secured and separate from the public phone network, by design. Sometimes, on calls using land lines, the originating telephone number may not be passed to the PSAP at all, generally because the number is not in the ALI database. When this happens, the call receiver must confirm the location of the incoming call, and may have to redirect the call to another, more appropriate PSAP. ALI Failure occurs when the phone number is not passed or the phone number passed is not in the ALI database. In most jurisdictions, when ALI database lookup failure occurs, the telephone company has a legal mandate to fix the database entry.

Funding 9-1-1 services

In the United States, 9-1-1 and enhanced 9-1-1 are typically funded based on state laws that impose monthly fees on local and wireless telephone customers. In Canada, a similar fee for service structure is regulated by the federal Canadian Radio Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). Depending on the location, counties and cities may also levy a fee, which may be in addition to, or in lieu of, the state fee. The fees are collected by local telephone and wireless carriers through monthly surcharges on customer telephone bills. The collected fees are remitted to 9-1-1 administrative bodies, which may be statewide 9-1-1 boards, state public utility commissions, state revenue departments, or local 911 agencies.[24] These agencies disburse the funds to the Public Safety Answering Points for 9-1-1 purposes as specified in the various statutes. Telephone companies in the United States, including wireless carriers, may be entitled to apply for and receive reimbursements for costs of their compliance with federal and state laws requiring that their networks be compatible with 9-1-1 and enhanced 9-1-1.

Fees vary widely by locality. They may range from around $.25 per month to $3.00 per month, per line.[25] The average wireless 9-1-1 fee in the United States, based on the fees for each state as published by the National Emergency Number Association (NENA), is around $0.72. Since monthly fees do not vary based on the customer's usage of the network, the fees are considered, in tax terms, as highly "regressive", i.e., the fees disproportionately burden low-volume users of the public switched network (PSN) as compared with high-volume users. Some states cap the number of lines subject to the fee for large multi-line businesses, thereby shifting more of the fee burden to low-volume single-line residential customers or wireless customers.

Problems requiring further resolution

Wireless telephones

Dialing 9-1-1 from a mobile phone (Cellular/PCS) in the United States originally connected the call to the state police or highway patrol, instead of the local public safety answering point (PSAP).[26] The caller had to describe an exact location so that the agency could transfer the call to the correct local emergency services. This was a regular problem, because the exact location of the cellular phone isn't normally transmitted with the voice call, and with the exponential growth of cellular use, such calls were frequent occurrences.

In 2000, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued an order requiring wireless carriers to determine and transmit the location of callers who dial 9-1-1. The FCC set up a phased program: Phase I transmitted the location of the receiving antenna for 9-1-1 calls, while Phase II transmitted the location of the calling telephone. The order set up certain accuracy requirements and other technical details, and milestones for completing the implementation of wireless location services. Subsequent to the FCC's order, many wireless carriers requested waivers of the milestones, and the FCC granted many of them. By mid-2005, the process of Phase II implementation was generally underway, but limited by the complexity of the coordination required from wireless carriers, PSAPs, local telephone companies and other affected government agencies, and the limited funding available to local agencies which need to convert PSAP equipment to display location data (usually on computerized maps). Such rules do not apply in Canada.[27]

FCC rules require that all new mobile phones will provide their latitude and longitude to emergency operators in the event of a 9-1-1 call. Carriers may choose whether to implement this via Global Positioning System (GPS) chips in each phone, or by means of triangulation between cell towers. Due to limitations in technology (of the mobile phone, cellular phone towers, and PSAP equipment), a mobile caller's geographical information may not always be available to the local PSAP. Technologies are currently under development to remedy this situation and improve performance.[28] Although there are now technological ways to obtain the geographical location of the caller, a 9-1-1 caller should try to be aware of the location of the incident about which he or she is calling.

Inactive telephones

In the U.S., Federal Communications Commission rules require every telephone that can access the network to be able to dial 9-1-1, regardless of any reason that normal service may have been disconnected (including non-payment) (This only applies to states with a Do Not Disconnect policy in place. Those states must provide a "soft" or "warm" dial tone service, details can be found at http://www.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Common_Carrier/Reports/FCC-State_Link/IAD/pntris99.pdf) On wired (land line) phones, this usually is accomplished by a "soft" dial tone, which sounds normal but will allow only emergency calls. Often, an unused and unpublished phone number will be issued to the line so that it will work properly. With regard to mobile phones, the rules require carriers to connect 9-1-1 calls from any mobile phone, regardless of whether that phone is currently active.[29] The same rules for inactive telephones apply in Canada.[30]

When a cellular phone is deactivated, the phone number is often recycled to a new user, or to a new phone for the same user. The deactivated cell phone will still complete a 911 call (if it has battery power) but the 911 operator will see a specialized number indicating the cell phone has been deactivated. It is usually represented with an area code of (911)-xxx-xxxx. If the call is disconnected, the 911 operator will not be able to connect to the original caller. Also because the cell phone is no longer activated, the 911 operator is often unable to get Phase II information.[31]

Internet telephony

This article appears to contradict the article VoIP#Emergency_calls. |

If 9-1-1 is dialed from a commercial Voice Over Internet Protocol (VoIP) service, depending on how the provider handles such calls, the call may not go anywhere at all, or it may go to a non-emergency number at the public safety answering point associated with the billing or service address of the caller.[32] Because a VoIP adapter can be plugged into any broadband internet connection, a caller could actually be hundreds or even thousands of miles away from home, yet if the call goes to an answering point at all, it would be the one associated with the caller's address and not the actual location of the call. It may never be possible to reliably and accurately identify the location of a VoIP user, even if a GPS receiver is installed in the VoIP adapter, since such phones are normally used indoors, and thus may be unable to get a signal.

In March 2005, commercial Internet telephony provider Vonage was sued by the Texas attorney general, who alleged that their website and other sales and service documentation did not make clear enough that Vonage's provision of 9-1-1 service was not done in the traditional manner. In May 2005 the FCC issued an order requiring VoIP providers to offer 9-1-1 service to all their subscribers within 120 days of the order being published.[33] The order set off anxiety among many VoIP providers, who felt it will be too expensive and require them to adopt solutions that won't support future VoIP products.[citation needed] In Canada, the federal regulators have required Internet Service Providers (ISPs), to provide an equivalent service to the conventional PSAPs, but even these encounter problems with caller location, since their databases rely on company billing addresses.[34]

In May 2010, most VoIP users who dial 9-1-1 are connected to a call center owned by their telephone company, or contracted by them. The operators are most often not trained emergency service providers, and are only there to do their best to connect the caller to the appropriate emergency service. If the call center is able to determine the location of the emergency they try to transfer the caller to the appropriate PSAP. Most often the caller ends up being directed to a PSAP in the general area of the emergency. A 9-1-1 operator at that PSAP must then determine the location of the emergency, and either send help directly, or transfer the caller to the appropriate emergency service. In April 2008, an 18-month-old boy in Calgary, Alberta died after a VoIP provider's 9-1-1 operator had an ambulance dispatched to the address of the boy's family's ISP, which is in Mississauga, Ontario.[35]

Nine-One-One vs. Nine-Eleven

When the 9-1-1 system was originally introduced, it was advertised as the "nine-eleven" service. The advertising was changed when concerns were expressed that some types of callers, most notably smaller children, tend to be very literal, and might waste emergency response time trying to find a non-existent "eleven" key on their telephones.[36][37][38] Therefore, all references to the telephone number 9-1-1 are now always made as "nine-one-one", and never as "nine-eleven", according to standards outlined by the National Emergency Number Association (NENA). Some newspapers and other media require that references to the phone number be formatted as 9-1-1, also a suggested standard by NENA.[39] Since September 11, 2001, "nine-eleven" is used almost exclusively to refer to the September 11, 2001 attacks. In Spanish, 9-1-1 is known as novecientos once (nine hundred and eleven), or "nueve once ", which means "nine eleven" and rarely as "nueve uno uno", the literal translation of "nine-one-one".

Dialing patterns

The choice of 9-1-1 as the emergency services number causes dialing-pattern problems in many hotels and businesses. Some hotels, for example, have been known to require dialing "91+" to make an outside call. This leads numbers being dialed such as 91+1+301+555+2368. Since this is a valid telephone number which starts with the digits 911, and is not a call to an emergency service, a timeout becomes necessary on calls dialed literally as 911 to avoid accidental calls to the emergency number. Such prefixes for dialing outside calls are strongly discouraged by telephone companies for this reason.

The need to avoid accidental 9-1-1 calls is also part of the reasoning behind why no area code starts with a "1": the slightly less troublesome "outside line" prefix of "9+" would then cause the same problem: "9+114+555+2368", for example.

This is still a daily issue with long distance calling in places that require an "outside line" prefix, like every business that uses a PBX of any type. Every long distance number starts "9+1+" and, the possibility of mis-dialing and pressing the "1" twice, still causes a problem.

Requiring an "outside line" prefix also means that to complete an intended call to 9-1-1 from a hotel or business that uses a prefix, a caller would have to know to dial the "outside line" prefix first, rendering the emergency number as 91-9-1-1 or 9-9-1-1. However, some phone systems that require "9" to get an outside line can recognize the dialed pattern 9-1-1 (without a previous "9") and connect to the PSAP without error.

Another possible problem with 9-1-1 dialing is that the international phone code for India is "91", and sometimes calls meant for India end up at local emergency dispatch offices if a caller did not first dial the international call prefix 011.

Emergencies across jurisdictions

When a caller dials 9-1-1, the call is routed to the local public safety answering point. However, if the caller is reporting an emergency in another jurisdiction, the dispatchers may or may not know how to contact the proper authorities. The publicly posted phone numbers for most police departments in the U.S. are non-emergency numbers that often specifically instruct callers to dial 9-1-1 in case of emergency, which does not resolve the issue for callers outside of the jurisdiction. In the age of both commercial and personal high speed Internet communications, this issue is becoming an increasing problem.

In the Pennsylvania suburbs of Philadelphia, telephone exchanges frequently cross county lines. For example, a 9-1-1 call placed from Warminster, which is in Bucks County, may be misdirected to the Montgomery County PSAP because most of Warminster is served by the Hatboro telephone exchange, which is located in Montgomery County. Telford, Pennsylvania sits in both counties and the PSAP must determine in which county the call originated.

NENA has developed the North American 9-1-1 Resource Database which includes the National PSAP Registry. PSAPs can query this database to obtain emergency contact information of a PSAP in another county or state when it receives a call involving another jurisdiction. Online access to this database is provided at no charge for authorized local and state 9-1-1 authorities.[40]

Making calls public

In recent years, 911 calls have aired on news broadcasts.

Ohio Senator Tom Patton introduced a bill in 2009 which would have banned the broadcasting of 911 calls, requiring the use of transcripts instead. Patton believed that people would be reluctant to make calls because of possible retaliation or threats against those who called. He intended to seek proof of this idea to satisfy those who did not believe him, or that broadcasting 911 calls hurt investigations. The Ohio Fraternal Order of Police supported the bill because broadcasts of 911 calls just "sensationalized".[41] Ohio Association of Broadcasters director Chris Merritt said government did not have the right to decide how public records were used.[42] Other opponents of such a ban point out that recordings hold dispatchers accountable and show when they are not doing their jobs properly, in a way transcripts cannot.[43][44]

A bill signed by Alabama governor Bob Riley on April 27, 2010 requires a court order before recordings can be made public. Alaska, Florida, Kentucky and Wisconsin also had bills banning the broadcasts.[45] Mississippi, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Wyoming already banned the broadcasts.[46]

In April 2011, the Tennessee Senate passed a bill banning broadcasts of calls unless the caller gave permission.[47]

A North Carolina law will require news media to use either transcripts or distorted voices.[48]

GPS locator

According to FCC rule, by 2018 all phone handsets have to be GPS-capable to better aid in pin-pointing the location of 911 calls. The rule should be followed by all telephone service providers, including VOIP services. It's still unclear what the sunset deadline for using old non-GPS phones.[49]

See also

- eCall

- Emergency Medical Dispatcher

- Emergency telephone

- Emergency telephone number

- Enhanced 911

- In case of emergency (ICE) entry in the mobile phone book

- Next Generation 9-1-1

- Northern 911

- Other places' emergency phone numbers:

References

- ^ Police nab fourth teen after hoax 911 calls

- ^ More arrests possible in prank 911 calls

- ^ "History of the Telephone (Privateline.com website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Officially Recommended Exchange Names (website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Ambulance Dispatching in Toronto Since 1832 (Toronto EMS website)". Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ "Next Generation 911 (Firehouse magazine website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ BT plc (2007-06-29). "999 celebrates its 70th birthday". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Winnipeg Police History website". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Winnipegers Call 999 for Help (CBC Digital Archives website". CBC News. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "911 Facts 1 (NENA website)". Archived from the original on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "911 Facts 2 (NENA website)". Archived from the original on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "CRTC Guidelines". Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "N11 Numbers (FCC website)". Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "About NANPA (website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "History of the North American Numbering System (website)". Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ Establishing 911 at Haleyville Alabama

- ^ Robertson, Grant (2008-12-19). "Canada's 9-1-1 emergency". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ "9-1-1 (FCC website)". Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ "What is NG9-1-1? (NENA website)" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Washington State Legislature website". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "U.S. Patent#6526125 (PatentStorm website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Enhanced 9-1-1" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ "What is ANI? (website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Santa Cruz County (Calif.) Board of Supervisors website" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Range of 911 User Fees" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "9-1-1 From Your Cellphone (Berkley (Ca) Police website)". Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "The Good and Bad News About Cellphones". Retrieved 2008-11-03. [dead link]

- ^ "U.S. Patent #6697630 (freepatentsonline website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Denton County (Ga.) 9-1-1 website". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Calling 9-1-1 (City of Calgary website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16. [dead link]

- ^ "Old cell phones give dispatchers headache". Deseret News. 2007-04-23.

- ^ "911VoIp FAQs". Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "9-1-1 Services (FCC website)". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "CRTC Decision on 9-1-1 Emergency Services for VoIP Service Providers" (Press release). Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. 2005-04-04. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ^ CBC News (2008-04-30). "Calgary toddler dies after family calls 911 on internet phone". Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ^ "9-1-1 FAQ". Santa Rosa County Emergency Management Office. Santa Rosa County, Florida. Retrieved on December 29, 2008.

- ^ "9-1-1 Caller Tips". Emergency Communications Center. Metropolitan Government of Nashville & Davidson County, Tennessee. Retrieved 2008-12-29. [dead link]

- ^ "What Is 9-1-1?". Pierce County Enhanced 9-1-1 Program Office, Pierce County Department of Emergency Management. Pierce County, Washington. March 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ "National Emergency Number Association website". Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "NENA 9-1-1 Resource DB". Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ^ Fields, Reginald (2010-01-11). "State Sen. Tom Patton wants to bar broadcast of 9-1-1 calls". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ^ "An end to 911 call replays?". WJW-TV. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ^ "States eye ban on public release of 911 calls". MSNBC. Associated Press. 2010-02-23. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ^ Berke, Ronni; Costello (2009-05-15). CNN [An end to 911 call replays? An end to 911 call replays?]. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help); More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help) - ^ Andrews, Curry (Spring 2010). "State proposals would limit access to 911 calls". The News Media & The Law. RCFP.

- ^ Carrabine, Nick (2010-04-04). "Legislation would ban broadcast of 911 calls on radio, TV, Web". The News-Herald. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- ^ "Bill to Protect 911 Callers Passes Tenn. Senate". WTVC. 2011-04-21. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- ^ Anderson, Taylor (2011-08-14). "911 tapes to be altered to distort voices". News & Observer. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ "FCC Wants GPS In Every Phone By 2018". Retrieved October 5, 2011.