Carnegie library

- For other uses, see Carnegie Library (disambiguation)

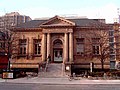

A Carnegie library is a library built with money donated by Scottish-American businessman and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. 2,509 Carnegie libraries were built between 1883 and 1929, including some belonging to public and university library systems. 1,689 were built in the United States, 660 in Britain and Ireland, 125 in Canada, and others in Australia, New Zealand, Serbia, the Caribbean, and Fiji. Few towns that requested a grant and agreed to his terms were refused. When the last grant was made in 1919, there were 3,500 libraries in the United States, nearly half of them built with construction grants paid by Carnegie.[citation needed]

History

The first of Carnegie's public libraries opened in his hometown, Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1883. The locally quarried sandstone building displays a stylised sun with a carved motto - "Let there be light" at the entrance. His first library in the United States was built in 1889 in Braddock, Pennsylvania, home to one of the Carnegie Steel Company's mills. Initially Carnegie limited his support to a few towns in which he had an interest. From the 1890s on, his foundation funded a dramatic increase in number of libraries. This coincided with the rise of women's clubs in the post-Civil War period, which were most responsible for organizing efforts to establish libraries, including long-term fundraising and lobbying within their communities to support operations and collections.[1] They led the establishment of 75-80 percent of the libraries in communities across the country.[2]

Carnegie believed in giving to the "industrious and ambitious; not those who need everything done for them, but those who, being most anxious and able to help themselves, deserve and will be benefited by help from others."[3] Under segregation black people were generally denied access to public libraries in the Southern United States. Rather than insisting on his libraries being racially integrated, he funded separate libraries for African Americans. For example, at Houston he funded a separate Colored Carnegie Library.[4]

Most of the library buildings were unique, constructed in a number of styles, including Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance, Baroque, Classical Revival, and Spanish Colonial. Scottish Baronial was one of the styles used in Carnegie's native Scotland. Each style was chosen by the community, although as the years went by James Bertram, Carnegie's secretary, became less tolerant of designs which were not to his taste.[citation needed] Edward Lippincott Tilton, a friend often recommended by Bertram, designed many of the buildings.[5] The architecture was typically simple and formal, welcoming patrons to enter through a prominent doorway, nearly always accessed via a staircase. The entry staircase symbolized a person's elevation by learning. Similarly, outside virtually every library was a lamppost or lantern,[citation needed] meant as a symbol of enlightenment.

In the early 20th century, a Carnegie library was often the most imposing structure in hundreds of small American communities.

-

Carnegie Free Library of Braddock in Braddock, Pennsylvania, built in 1888, was the first Carnegie Library in the United States.

-

Carnegie Library in Houston, Texas (1904). The building was deemed too small fifteen years after it was built.

-

Detail of the entrance to the Carnegie Library in Avondale, Cincinnati (1902). (Spanish colonial style)

-

Carnegie Library opened in 1916 in Grass Valley, California. (neoclassical style).

-

Carnegie Library in Hull, England now houses the Carnegie Heritage Centre. (Half-timbered architecture)

-

Carnegie Library in Iron Mountain, Michigan. It now houses a history museum.

Background

Books and libraries were important to Carnegie, beginning with his childhood in Scotland. There he listened to readings and discussions of books from the Tradesman's Subscription Library, which his father helped create.[citation needed] Later, in the United States, while working for the local telegraph company in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, Carnegie borrowed books from the personal library of Colonel James Anderson, who opened the collection to his workers every Saturday.

In his autobiography, Carnegie credited Anderson with providing an opportunity for "working boys" (that some said should not be "entitled to books") to acquire the knowledge to improve themselves.[6] Carnegie's personal experience as an immigrant, who with help from others worked his way into a position of wealth, reinforced his belief in a society based on merit, where anyone who worked hard could become successful. This conviction was a major element of his philosophy of giving in general,[citation needed] and of his libraries as its best known expression.

"The Carnegie Formula"

Nearly all of Carnegie's libraries were built according to "The Carnegie Formula", which required matching contributions from the town that received the donation.[citation needed] It must:

- demonstrate the need for a public library;

- provide the building site;

- annually provide ten percent of the cost of the library's construction to support its operation; and,

- provide free service to all.

Carnegie assigned the decisions to his assistant James Bertram. He created a "Schedule of Questions." The schedule included: Name, status and population of town, Does it have a library? Where is it located and is it public or private? How many books? Is a town-owned site available?

One of the requirements was the willingness of people and government to raise taxes to support the library. Money was not given all at once but disbursed gradually as the project went on. Records were kept on a "Daily Register of Donations." The 1908 Daily register of donations, for example, has 10–20 entries each day.[citation needed] Every day that year, money was disbursed for libraries and church organs in the US and Britain.

The amount of money donated to most communities was based on U.S. Census figures and averaged approximately $2 per person.[citation needed] Many communities were eager for the chance to build public institutions. James Bertram, Carnegie's personal secretary who ran the program, was never without requests.

The impact of Carnegie's library philanthropy was maximized by his timing. His offers came at a peak of town development and library expansion in the US.[citation needed] By 1890, many states had begun to take an active role in organizing public libraries, and the new buildings filled a tremendous need. Interest in libraries was also heightened at a crucial time in their early development by Carnegie's high profile and his genuine belief in their importance.[7]

Self-service stacks

The design of the Carnegie libraries has been given credit[who?] for encouraging communication with the librarian. It also created an opportunity for people to browse and discover books on their own. "The Carnegie libraries were important because they had open stacks which encouraged people to browse....People could choose for themselves what books they wanted to read," according to Walter E. Langsam, an architectural historian and teacher at the University of Cincinnati. Before Carnegie, patrons had to ask a clerk to retrieve books from closed stacks.[8]

Continuing legacy

Carnegie established charitable trusts which have continued his philanthropic work. However, even before his death they had reduced their involvement in the provision of libraries. There has continued to be support for library projects, for example in South Africa.[9]

In 1992, the New York Times reported that according to a survey conducted by Dr. George Bobinksi, dean of the School of Information and Library Studies at the State University at Buffalo 1,554 of the 1,681 original buildings in the United States still existed, with 911 still used as libraries. Two-hundred seventy six were unchanged, 286 had been expanded, and 175 had been remodeled. Two-hundred forty three had been demolished while others had been converted to other uses..[10]

While hundreds of the library buildings have become museums, community centers, office buildings, residences, or are otherwise used more than half of those in the United States still serve their communities as libraries over a century after their construction,[11] many in middle- to low-income neighborhoods. For example, Carnegie libraries still form the nucleus of the New York Public Library system in New York City, with 31 of the original 39 buildings still in operation. Also, the main library and eighteen branches of the Pittsburgh public library system are Carnegie libraries. The public library system there is named the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.[12]

In the late 1940s, the Carnegie Corporation of New York arranged for microfilming of the correspondence files relating to Andrew Carnegie's gifts and grants to communities for the public libraries and church organs. They then discarded the original materials. The microfilms are open for research as part of the Carnegie Corporation of New York Records collection, residing at Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Unfortunately archivists did not microfilm photographs and blueprints of the Carnegie Libraries. The number and nature of documents within the correspondence files varies widely. Such documents may include correspondence, completed applications and questionnaires, newspaper clippings, illustrations, and building dedication programs. UK correspondence files relating to individual libraries have been preserved in Edinburgh (see the article List of Carnegie libraries in Europe).

Beginning in the 1930s, some libraries were meticulously measured, documented and photographed under the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) program of the National Park Service,[14] and other documentation has been collected by local historical societies. In 1935, the centenniel of his Carnegie's birth, a copy of the portrait of him originally painted by F. Luis Mora was given to libraries he help fund..[15] Many of the Carnegie libraries in the United States, whatever their current uses, have been recognized by listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Lists of Carnegie libraries

- List of Carnegie libraries in Africa, the Caribbean and Oceania

- List of Carnegie libraries in Canada

- List of Carnegie libraries in Europe

- List of Carnegie libraries in the United States

Notes

- ^ Paula D. Watson, “Founding Mothers: The Contribution of Women’s Organizations to Public Library Development in the United States”, Library Quarterly, Vol. 64, Issue 3, 1994, p.236

- ^ Teva Scheer, “The “Praxis” Side of the Equation: Club Women and American Public Administration”, Administrative Theory & Praxis, Vol. 24, Issue 3, 2002, p.525

- ^ Andrew Carnegie, "The Best Fields for Philanthropy", The North American Review, Volume 149, Issue 397, December, 1889 from the Cornell University Library website

- ^ This library has been discussed in Cheryl Knott Malone's essay, "Houston's Colored Carnegie Library, 1907–1922", which while still in manuscript won the Justin Winsor Prize in 1997. Accessed on-line August 2008 in a revised version

- ^ Mausolf, Lisa B. (2007), Edward Lippincott Tilton: A Monograph on His Architectural Practice (PDF), retrieved 2011-09-28,

Many of these were Carnegie Libraries, public libraries built between 1886 and 1917 with funds provided by Andrew Carnegie or the Carnegie Corporation of New York. In all, Carnegie funding was provided for 1,681 public library buildings in 1,412 U.S. communities, with additional libraries abroad. Increasingly after 1908, Carnegie library commissions tended to be in the hands of a relatively small number of firms that specialized in library design. Tilton benefited from a friendship with James Bertram, who was responsible for reviewing plans for Carnegie-financed library buildings. Although the Carnegie program left the hiring of an architect to local officials, Bertram's personal letters of introduction gave Tilton a distinct advantage. As a result, Tilton won a large number of comparatively modest Carnegie library commissions, primarily in the northeast. Typically, Tilton furnished all plans, working drawings, details and specifications and then associated with a local architect who would supervise construction and receive 5% of Tilton's commission.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Andrew Carnegie: A Tribute: Colonel James Anderson", Exhibit, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

- ^ Bobinski, p. 191

- ^ Al Andry, "New Life for Historic Libraries", The Cincinnati Post, October 11, 1999

- ^ The Carnegie Corporation and South Africa: Non-European Library Services Libraries & Culture, Volume 34, No. 1 (Winter 1999), from the University of Texas at Austin

- ^ Strum, Charles (March 02, 1992), "BELLEVILLE JOURNAL; Restoring Heritage and Raising Hopes for Future", The New York Times, retrieved 2011-09-29,

Dr. George Bobinksi, dean of the School of Information and Library Studies at the State University at Buffalo, says 1,681 libraries were built with Carnegie money, mostly between 1898 and 1917.In a survey, he found that at least 1,554 of the buildings still exist, with only 911 of these still in use as public libraries. At least 276 of the survivors are unchanged, while 243 have been demolished, 286 have been expanded and 175 have been remodeled. Others have been turned into condominiums, community centers or shops.

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Carnegie libraries by state" (PDF). American Volksporting Association. 1996. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ http://www.carnegielibrary.org/

- ^ National Portrait Gallery catalogue

- ^ Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER), Permanent Collection, American Memory from the Library of Congress

- ^ "Belmar Public Library". Wall, New Jersey. Amercian towns. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

References

- Molly Skeen (March 5, 2004) "How America's Carnegie Libraries Adapt to Survive", Preservation Online.

- December 10, 2002. "Yorkville Library Celebrates Centennial", The New York Public Library.

- Michael Lorenzen (1999). "Deconstructing the Carnegie Libraries: The Sociological Reasons Behind Carnegie's Millions to Public Libraries", Illinois Libraries. 81, no. 2: 75–78.

- Theodore Jones (1997). Carnegie Libraries Across America: A Public Legacy, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-14422-3

- George Bobinski (1969). Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development, American Library Association. ISBN 0-8389-0022-4

- Brendan Grimes (1998). Irish Carnegie Libraries: A catalogue and architectural history, Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2618-2

- Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

External links

- Carnegie Collections from the Columbia University Library System website

- "Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright", National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan

- Selected websites for Carnegie Libraries in specific countries or U.S. states

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |