Climate change in the United States

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (September 2010) |

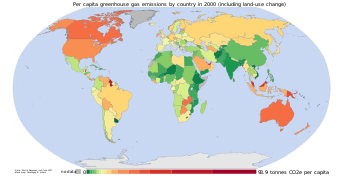

There is an international interest in issues surrounding global warming in the United States due to the U.S. position in world affairs and the U.S.'s high level of greenhouse gas emissions per capita.

Greenhouse gas emissions by the United States

The United States was the second top emitter by fossil fuels CO2 in 2009 5,420 mt (17.8% world total), and the second top of all greenhouse gas emissions including construction and deforestation in 2005 US: 6,930 mt (15.7% of world total). In the cumulative emissions between 1850 and 2007 US was top country 28.8% of the world total.[1]

Until recently the United States for the country as a whole was the largest emitter of carbon dioxide but as of 2006 China has become the largest emitter. However per capita emission figures of China are still about one quarter of those of the US population.[2] On a per capita basis the U.S. is ranked the seventh highest emitter of greenhouse gases and fourteenth when land use changes are taken into account.

According to data from the US Energy Information Administration the top emitters by fossil fuels CO2 in 2009 were: China: 7,710 million tonnes (mt) (25.4%), US: 5,420 mt (17.8%), India: 5.3%, Russia: 5.2% and Japan: 3.6%.[1]

In the cumulative emissions between 1850 and 2007 the top emitors were: 1. US 28.8%, 2. China: 9.0%, 3. Russia: 8.0%, 4. Germany 6.9%, 5. UK 5.8%, 6. Japan: 3.9 %, 7. France: 2.8%, 8. India 2.4%, 9. Canada: 2.2% and 10. Ukraine 2.2%.[3]

The Environmental Protection Agency's Personal Emissions Calculator[4] is a tool for measuring the impact that individual choices (often money saving) can have.

Potential effects of climate change in the United States

According to Stern report with warming of 3 or 4°C there will be serious risks and increasing pressures for coastal protection in New York.[5]

In 2009 climate change was underway in the United States and was projected to grow. Crop and livestock production will be increasingly challenged. Threats to human health will increase.[6][7]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) website provides information on climate change: EPA Climate Change. Climate change is a problem that is affecting people and the environment. Human-induced climate change has, e.g., the potential to alter the prevalence and severity of extreme weathers such as heat waves, cold waves, storms, floods and droughts.[8]

According to the US Climate Change Science Programme: "With continued global warming, heat waves and heavy downpours are very likely to further increase in frequency and intensity. Substantial areas of North America are likely to have more frequent droughts of greater severity. Hurricane wind speeds, rainfall intensity, and storm surge levels are likely to increase. The strongest cold season storms are likely to become more frequent, with stronger winds and more extreme wave heights."[9]

NOAA had registered in August 2011 nine distinct extreme weather disasters, each totalling $1bn or more in economic losses. Total losses for 2011 were evaluated as more than $35bn before Hurricane Irene.[10]

Policy

The politics of global warming is played out at a state and federal level in the United States. Attempts to draw up climate change policy are being made at a state level to a greater extent than at a federal level.

Federal policy

The United States, although a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, has neither ratified nor withdrawn from the protocol. In 1997, the US Senate voted unanimously under the Byrd–Hagel Resolution that it was not the sense of the senate that the United States should be a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol. In 2001, former National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, stated that the Protocol "is not acceptable to the Administration or Congress".[11]

In March 2001, the Bush Administration announced that it would not implement the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty signed in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan that would require nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, claiming that ratifying the treaty would create economic setbacks in the U.S. and does not put enough pressure to limit emissions from developing nations.[12] In February 2002, Bush announced his alternative to the Kyoto Protocol, by bringing forth a plan to reduce the intensity of greenhouse gasses by 18 percent over 10 years. The intensity of greenhouse gasses specifically is the ratio of greenhouse gas emissions and economic output, meaning that under this plan, emissions would still continue to grow, but at a slower pace. Bush stated that this plan would prevent the release of 500 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, which is about the equivalent of 70 million cars from the road. This target would achieve this goal by providing tax credits to businesses that use renewable energy sources.[13]

Climate scientist James E. Hansen, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, claimed in a widely cited New York Times article [14] in 2006 that his superiors at the agency were trying to "censor" information "going out to the public." NASA denied this, saying that it was merely requiring that scientists make a distinction between personal, and official government, views in interviews conducted as part of work done at the agency. Several scientists working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have made similar complaints;[15] once again, government officials said they were enforcing long-standing policies requiring government scientists to clearly identify personal opinions as such when participating in public interviews and forums.

President Barack Obama said in September 2009 that if the international community would not act swiftly to deal with climate change that "we risk consigning future generations to an irreversible catastrophe...The security and stability of each nation and all peoples—our prosperity, our health, and our safety—are in jeopardy, and the time we have to reverse this tide is running out." [16] President Obama said in 2010 that it was time for the United States “to aggressively accelerate” its transition from oil to alternative sources of energy and vowed to push for quick action on climate change legislation, seeking to harness the deepening anger over the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[17] The 2010 United States federal budget proposed to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US $15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would be auctioned off, generating an estimated $78.7 billion in additional revenue in FY 2012, steadily increasing to $83 billion by FY 2019.[18]

State and regional policy

Across the country, regional organizations, states, and cities are achieving real emissions reductions and gaining valuable policy experience as they take action on climate change. These actions include increasing renewable energy generation, selling agricultural carbon sequestration credits, and encouraging efficient energy use.[19] The U.S. Climate Change Science Program is a joint program of over twenty U.S. cabinet departments and federal agencies, all working together to investigate climate change. In June 2008, a report issued by the program stated that weather would become more extreme, due to climate change.[20][21] States and municipalities often function as "policy laboratories", developing initiatives that serve as models for federal action. This has been especially true with environmental regulation—most federal environmental laws have been based on state models. In addition, state actions can have a significant impact on emissions, because many individual states emit high levels of greenhouse gases. Texas, for example, emits more than France, while California's emissions exceed those of Brazil.[22] State actions are also important because states have primary jurisdiction over many areas—such as electric generation, agriculture, and land use--that are critical to addressing climate change.

Many states are participating in Regional climate change initiatives, such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the northeastern United States, the Western Governors' Association (WGA) Clean and Diversified Energy Initiative, and the Southwest Climate Change Initiative.

International agreements

Chief US. negotiator in the Durban climate summit on 27 November 2011 was Todd Stern.[23]

Public response

Voluntary emissions trading

Also in 2003, U.S. corporations were able to trade CO2 emission allowances on the Chicago Climate Exchange under a voluntary scheme. In August 2007, the Exchange announced a mechanism to create emission offsets for projects within the United States that cleanly destroy ozone-depleting substances.[24]

Campus-level action

Many colleges and universities have taken steps in recent years to offset or curb their greenhouse gas emissions in relation to campus activities. On October 5, 2006, New York University announced that it plans to purchase 118 million kilowatt hours of wind power, more wind power than any college or university in the country.[25] Later in the same month, the small campus of College of the Atlantic in Maine became the first to vow to offset all of its greenhouse gas emissions by cutting GHG emissions and investing in emissions-cutting projects elsewhere.[26] In May 2007, the trustees of Middlebury College voted in support of a student-written proposal[27] to reduce campus emissions as much as possible, and then offset the rest such that the campus is carbon neutral by 2016.[28] As of November 2007, 434 campuses have institutionalized their commitment to climate neutrality by signing the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment.[29] On November 2-5th, 2007, thousands of young adults converged in Washington D.C. for Power Shift 2007, the first national youth summit to address the climate crisis.[30] The Power Shift 2007 conference was a project of the Energy Action Coalition.[31]

Public perceptions

In Europe, the notion of human influence on climate gained wide acceptance more rapidly than in many other parts of the world, most notably the United States.[32][33] There is growing awareness in the US, such as with 350.org (based in the US) and the International Day of Climate Action.[34]

The table below shows how public perceptions about the existence and importance of global warming have changed in the U.S. and elsewhere.[35][36][37][38]

| Statement | Agreement (World) |

Agreement (US) |

|---|---|---|

| Global warming is probably occurring. | 85% (2006) 80% (1998) | |

| Human activity is a significant cause of climate change. | 79% (2007) | 71% (2007) |

| Climate change is a serious problem. | 90% (2006) 78% (2003) |

76% (2006) |

| It's necessary to take major steps starting very soon. | 65% (2007) | 59% (2007) |

Historical support for environmental protection has been relatively non-partisan. Republican Theodore Roosevelt established national parks whereas Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Soil Conservation Service. This non-partisanship began to change during the 1980s when the Reagan administration stated that environmental protection was an economic burden. Views over global warming began to seriously diverge among Democrats and Republicans during Kyoto in 1998. Gaps in opinions among the general public are often amplified among the political elites, such as members of Congress, who tend to be more polarized.[39]

Our Changing Planet

Since 1989, the U.S. Global Change Research Program has issued Our Changing Planet, an annual report summarizing "recent achievements, near term plans, and progress in implementing long term goals." (http://globalchange.gov/publications/our-changing-planet-ocp) The most recent report, for fiscal year 2010, was issued on October 28, 2009.

Measurement and modeling of climate systems have both improved dramatically in the last three decades, with measurements providing the hard data to calibrate the simulations, which in turn lead to improved understanding of the various systems and feedbacks and indicate areas where more and more detailed observations are needed. Recent developments in ensemble methods have improved understanding of and reduced uncertainty in hydrologic forcing by incoming radiation, particularly in areas with a complex topology. Multiple complementary model-validated proxy reconstructions indicate that recent warmth in the northern hemisphere is anomalous over at least the last 1300 years; using tree ring data, this conclusion can be extended somewhat less certainly to at least 1700 years. Improved measurement and analysis techniques have reconciled certain discrepancies between observed and projected trends in tropical surface and tropospheric temperatures: corrected buoy and satellite surface temperatures are slightly cooler and corrected satellite and radiosonde measurements of the tropical troposphere are slightly warmer.

Various forcing factors, including greenhouse gases, land cover change, volcanoes, air pollution and aerosols, and solar variability, have far ranging effects throughout the coupled ocean-atmosphere-land climate system. In the short term, impacts from ozone, black carbon, organic carbon, and sulfate on radiative forcing are predicted to nearly cancel, but long term projection of changing emissions patterns indicate that the warming impact of black carbon will outweigh the cooling impact of sulphates. By 2100, the projected global average increase to radiative forcing is approximately 1 W/m2.

Human activities influence climate and related systems through, among other mechanisms, land usage, water management, and earlier and more significant melting of snow cover due to greenhouse effect warming. In the southwestern United States, 60% of climate-related trends in river flow, winter air temperature, and snowpack between 1950 and 1999 were human induced. In this region, conversion of abandoned farmland to pine forests is projected to have a slight surface cooling effect, with evapotranspiration outweighing decreased albedo.

Climate change by state

California

California has taken legislative steps towards reducing the possible effects climate change by incentives and plans for clean cars, renewable energy and stringent caps on big polluting industries. In September 2006, the California State Legislature passed AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006[40] with the goal of reducing man-made California greenhouse gas emissions (1.4% of global emissions in 2004[41]) back to 1990 emission levels by 2020. The legislation grants the Air Resource Board extraordinary powers to set policies, draw up regulations, lead the enforcement effort, levy fines and fees to finance it and punish violators. The technical and regulatory requirements are far reaching. Some of this sweeping regulation is being challenged in the courts.[citation needed] The law is intended to make low-carbon technology more attractive, and promote its adoption in production in California.

Idaho

Idaho emits the least carbon dioxide per person of the United States, less than 23,000 pounds a year. Idaho forbids coal-power plants. It relies mostly on nonpolluting hydroelectric power from its rivers.[42][43] Over the last century, the average temperature near Boise, Idaho, has increased nearly 1°F, and precipitation has increased by nearly 20% in many parts of the state, and has declined in other parts of the state by more than 10%. These past trends may or may not continue into the future. Over the next century, climate in Idaho may experience additional changes. For example, based on projections made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and results from the United Kingdom Hadley Centre’s climate model (HadCM2), a model that accounts for both greenhouse gases and aerosols, by 2100 temperatures in Idaho could increase by 5 °F (2.8 °C) (with a range of 2-9°F) in winter and summer and 4 °F (2.2 °C) (with a range of 2-7°F) in spring and fall.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick has recently signed into law three global warming and energy-related bills that will promote advanced biofuels, support the growth of the clean energy technology industry, and cut the emissions of greenhouse gases within the state. The Clean Energy Biofuels Act, signed in late July, exempts cellulosic ethanol from the state's gasoline tax, but only if the ethanol achieves a 60% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions relative to gasoline. The act also requires all diesel motor fuels and all No. 2 fuel oil sold for heating to include at least 2% "substitute fuel" by July 2010, where substitute fuel is defined as a fuel derived from renewable non-food biomass that achieves at least a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. In early 2008 August , Governor Patrick signed two additional bills: the Green Jobs Act and the Global Warming Solutions Act. The Green Jobs Act will support the growth of a clean energy technology industry within the state, backed by $68 million in funding over 5 years. The Global Warming Solutions Act requires a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the state to 10%-25% below 1990 levels by 2020 and to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

Nevada

Climate change in Nevada has been measured over the last century, with the average temperature in Elko, Nevada, increasing 0.6°F (0.3°C), and precipitation has increased by up to 20% in many parts of the state. Based on projections made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and results from the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research climate model (HadCM2), a model that accounts for both greenhouse gases and aerosols, by 2100, temperatures in Nevada could increase by 3-4°F (1.7-2.2°C) in spring and fall (with a range of 1-6°F [0.5-3.3°C]), and by 5-6°F (2.8-3.3°C) in winter and summer (with a range of 2-10°F [1.1-5.6°C]). Earlier and more rapid snowmelts could contribute to winter and spring flooding, and more intense summer storms could increase the likelihood of flash floods. Climate change could have an impact on crop production, reducing potato yields by about 12%, with hay and pasture yields increasing by about 7%. Farmed acres could rise by 9% or fall by 9%, depending on how climate changes. The region's inherently variable and unpredictable hydrological and climatic systems could become even more variable with changes in climate, putting stress on wetland ecosystems. A warmer climate would increase evaporation and shorten the snow season in the mountains, resulting in earlier spring runoff and reduced summer streamflow. This would exacerbate fire risk in the late summer. Many desert-adapted plants and animals already live near their tolerance limits, and could disappear under the hotter conditions predicted under global warming.

New York

Climate change in New York City could affect buildings/structures, wetlands, water supply, health, and energy demand, due to the high population and extensive infrastructure in the region.[44] New York is especially at risk if the sea level rises, due to many of the bridges connecting to boroughs, and entrances to roads and rail tunnels. High-traffic locations such as the airports, the Holland Tunnel, the Lincoln Tunnel, and the Passenger Ship Terminal are located in areas vulnerable to flooding.[45] Flooding would be expensive to reverse.[46][47] New York has launched a task force to advise on preparing city infrastructure for flooding, water shortages, and higher temperatures.[48]

Texas

Over the next century, climate in Texas could experience additional changes.[49] For example, based on projections made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and results from the United Kingdom Hadley Centre’s climate model (HadCM2), a model that accounts for both greenhouse gases and aerosols, by 2100 temperatures in Texas could increase by about 3 °F (~1.7 °C) in spring (with a range of 1-6°F) and about 4 °F (~2.2 °C) in other seasons (with a range of 1-9°F). Texas emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than any other state. And if Texas were a country, it would be the seventh-largest carbon dioxide polluter in the world . Texas's high carbon dioxide output and large energy consumption is primarily a result of large coal-burning power plants and gas-guzzling vehicles (low miles per gallon).[50] Unless increased temperatures are coupled with a strong increase in rainfall, water could become more scarce. A warmer and drier climate would lead to greater evaporation, as much as a 35% decrease in streamflow, and less water for recharging groundwater aquifers. Climate change could reduce cotton and sorghum yields by 2-15% and wheat yields by 43-68%, leading to changes in acres farmed and production. With changes in climate, the extent and density of forested areas in east Texas could change little or decline by 50-70%. Hotter, drier weather could increase wildfires and the susceptibility of pine forests to pine bark beetles and other pests, which would reduce forests and expand grasslands and arid shrublands.

Washington

Visible physical impacts on the environment within WA State include glacier reduction, declining snow-pack, earlier spring runoff, an increase in large wildfires, and rising sea levels which affect the Puget Sound area. Less snow pack will also result in a time change of water flow volumes into fresh water systems, resulting in greater winter river volume, and less volume during summer's driest months, generally from July through October. These changes will result in both economic and ecological repercussions, most notably found in hydrological power output, municipal water supply and migration of fish. Collectively, these changes are negatively affecting agriculture, forest resources, dairy farming, the WA wine industry, electricity, water supply, and other areas of the state.[51] Beyond affecting wildfires, climate change could impact the economic contribution of Washington’s forests both directly (e.g., by affecting rates of tree growth and relative importance of different tree species) and indirectly (e.g., through impacts on the magnitude of pest or fire damage).Beyond affecting wildfires, climate change could impact the economic contribution of Washington’s forests both directly (e.g., by affecting rates of tree growth and relative importance of different tree species) and indirectly (e.g., through impacts on the magnitude of pest or fire damage). Beyond growth rates, climate change could affect Washington forests by changing the range and life cycle of pests.

Washington State currently relies on hydro power for 72% of its power and sales of hydro power to both households and businesses topped 4.3 billion dollars in 2003. Washington State currently has the 9th lowest cost for electricity in the US. Climate change will have a negative effect on both the supply and demand of electricity in Washington.[52] The available electricity supply could also be affected by climate change. Currently, peak stream flows are in the summer. Snowpack is likely to melt earlier in the future due to increased temperatures, thus shifting the peak stream flow to late winter and early spring, with decreased summer stream flow. This would result in an increased availability of electricity in the early spring, when demand is dampened, and a decreased availability in the summer, when the demand may be highest. Currently the state generates $777 million in gains from power sales. However by 2020 they expect to see this fall to a deficit of $169 million and by 2040 a deficit of $730 million.

West Virginia

Warming and other climate changes could expand the habitat and infectiousness of disease-carrying insects, thus increasing the potential for transmission of diseases such as malaria and dengue (“break bone”) fever. Warmer temperatures could increase the incidence of Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases in West Virginia, because populations of ticks, and their rodent hosts, could increase under warmer temperatures and increased vegetation. Lower streamflows and lake levels in the summer and fall could affect the dependability of surface water supplies, particularly since many of the streams in West Virginia have low flows in the summer. Hay yields could increase by about 30% as a result of climate change, leading to changes in acres farmed and production. Farmed acres could remain constant or could decrease by as much as 30% in response to changes in prices, for example, possible decreases in hay prices. In areas where richer soils are prevalent, southern pines could increase their range and density, and in areas with poorer soils, which are more common in West Virginia’s forests, scrub oaks of little commercial value (e.g., post oak and blackjack oak) could increase their range. As a result, the character of forests in West Virginia could change. The state of West Virginia is 97% forested, and much of this cover is in high-elevation areas. These areas contain some of the last remaining stands of red spruce, which are seriously threatened by acid rain and could be further stressed by changing climate. Given a sufficient change in climate, these spruce forests could be substantially reduced, or could disappear. Higher-than-normal winter temperatures could boost temperatures inside cave bat roosting sites, which has been shown to cause higher mortality due to increased winter body weight loss in endangered Indiana bats (e.g., an increase of 9 °F (−13 °C) during winter hibernation has been associated with a 42% increase in the rate of body mass loss).

Wyoming

On a per-person basis, Wyoming emits more carbon dioxide than any other state or any other country: 276,000 pounds (125,000 kg) of it per capita a year, because of burning coal, which provides nearly all of the state's electrical power.[42] Warmer temperatures could increase the incidence of Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases in Wyoming, because populations of ticks, and their rodent hosts, could increase under warmer temperatures and increased vegetation. Increased runoff from heavy rainfall could increase water-borne diseases such as giardia, cryptosporidia, and viral and bacterial gastroenteritis. The headwaters of several rivers originate in Wyoming and flow in all directions into the Missouri, Snake, and Colorado River basins. A warmer climate could result in less winter snowfall, more winter rain, and faster, earlier spring snowmelt. In the summer, without increases in rainfall of at least 15-20%, higher temperatures and increased evaporation could lower streamflows and lake levels. Less water would be available to support irrigation, hydropower generation, public water supplies, fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, and mining. Hotter, drier weather could increase the frequency and intensity of wildfires, threatening both property and forests. Drier conditions would reduce the range and health of ponderosa and lodgepole forests, and increase their susceptibility to fire. Climate change also poses a threat to the high alpine systems, and this zone could disappear in many areas. Local extinctions of alpine species such as arctic gentian, alpine chaenactis, rosy finch, and water pipit could be expected as a result of habitat loss and fragmentation. In cooperation with the Wyoming Business Council, the Converse Area New Development Organization drafted an initiative to advance geothermal energy development in Wyoming. The Wyoming Business Council offers grants for homeowners who want to install photovoltaic (PV) systems.

See also

- U.S. Climate Change Science Program

- Climate change in the European Union

- Coal in the United States

- Energy conservation in the United States

- Environmental issues in the United States

- Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate

- Regional Clean Air Incentives Market (RECLAIM, an emission trading scheme in California)

- Renewable energy in the United States

- List of countries by greenhouse gas emissions per capita

References

- ^ a b World carbon dioxide emissions data by country: China speeds ahead of the rest Guardian 31 January 2011

- ^ Audra Ang (June 20, 2007). "Group: China tops world in CO2 emissions". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Which nations are most responsible for climate change? Guardian 21 April 2011

- ^ "Personal Emissions Calculator - Climate Change - What You Can Do". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Sir Nicholas Stern: Stern Review : The Economics of Climate Change, Executive Summary,10/2006 vi

- ^ Global Climate Change Impacts in the US 2009

- ^ http://downloads.globalchange.gov/usimpacts/pdfs/climate-impacts-report.pdf REPORT PDF

- ^ EPA Climate Change and http://epa.gov/climatechange/effects/extreme.html about Extreme weather

- ^ Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate US Climate Change Science Programme June 2008 Summary

- ^ Hurricanes, floods and wildfires – but Washington won't talk global warming Guardian 9 September 2011

- ^ Kluger, Jeffrey (2001-04-01). "A Climate Of Despair". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ Alex Kirby, US blow to Kyoto hopes, 2001-03-28, BBC News (online).

- ^ Bush unveils voluntary plan to reduce global warming, CNN.com, 2002-02-14.

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. (January 29, 2006). "Climate Expert Says NASA Tried to Silence Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ Eilperin, Julie (2006-04-06). "Climate Researchers Feeling Heat From White House". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ^ Phelps, Jordyn. "President Obama Says Global Warming is Putting Our Safety in Jeopardy". ABC News. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cooper, Helene (June 2, 2010). "Obama Says He'll Push for Clean Energy Bill". The New York Times.

- ^ "President's Budget Draws Clean Energy Funds from Climate Measure". Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ Engel, Kirsten and Barak Orbach (2008). "Micro-Motives for State and Local Climate Change Initiatives". Harvard Law & Policy Review, Vol. 2, pp. 119-137. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Schmid, Randolph E. (June 19, 2008). "Extreme weather to increase with climate change". Associated Press.

- ^ "U.S. experts: Forecast is more extreme weather". MSNBC. June 19, 2008.

- ^ Pew Center Climate change reports.

- ^ Q&A: Durban COP17 climate talks Guardian November 2011

- ^ Beyond the Kyoto six Carbon Finance 7 March 2008

- ^ http://www.newyorkbusiness.com/news.cms?id=14925 [dead link]

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (2006-10-10). "Maine College Makes Green Pledge". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ https://segue.middlebury.edu/index.php?&site=midd_shift§ion=15648&action=site [dead link]

- ^ http://www.middlebury.edu/about/pubaff/news_releases/2007/pubaff_633141333185905594.htm [dead link]

- ^ "American College & University Presidents;Climate Commitment".

- ^ http://powershift07.org/about [dead link]

- ^ Kamenetz, Anya (2007). "Climate Change Power Shift". The Nation.

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (4 January 2007). "More in Europe worry about climate than in U.S., poll shows". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ "Little Consensus on Global Warming – Partisanship Drives Opinion – Summary of Findings". Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ http://www.350.org

- ^ Weart, Spencer (2006). "The Public and Climate Change". In Weart, Spencer (ed.). The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ Langer, Gary (March 26, 2006). "Poll: Public Concern on Warming Gains Intensity". ABC News. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- ^ GlobeScan and the Program on International Policy Attitudes at University of Maryland (September 25, 2007). "Man causing climate change - poll". BBC World Service. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Program on International Policy Attitudes (April 5, 2006). "30-Country Poll Finds Worldwide Consensus that Climate Change is a Serious Problem". Program on International Policy Attitudes. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Dunlap, Riley E. (29 May 2009). "Climate-Change Views: Republican-Democratic Gaps Expand". Gallup. Retrieved 22 Dec 2009.

- ^ Text of AB 32

- ^ Brown, Susan J. "California Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trends and Selected Policy Options" (Slide presentation). California Energy Commission. [1]

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (2007-06-03). "Carbon-emissions culprit? Coal". The Seattle Times.

- ^ http://hydropower.id.doe.gov/resourceassessment/index_states.shtml?id=wy&nam=Wyoming

- ^ What major climate change impacts are projected for the coming decades? ."CIESIN . Earth Institute at Columbia University , n.d. Web. 16 Oct.2009. <http://ccir.ciesin.columbia.edu/nyc/ccir-ny_q2b.html>

- ^ "How will climate change affect the region’s transportation system?" CIESIN . Earth Institute at Columbia University, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2009. <http://ccir.ciesin.columbia.edu/nyc/ccir-ny_q2d.html>.

- ^ "What are the projected costs of climate change in the region’s coastal communities and coastal environments?" CIESIN. Earth Institute at Columbia University, n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2009. <http://ccir.ciesin.columbia.edu/nyc/ccir-ny_q2e.html>

- ^ Climate Change in New York.” NextGenerationEarth. The Earth Institute Columbia University, n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2009. <http://www.nextgenerationearth.org/contents/view/40>

- ^ "New York Launches Survival Strategy For Climate Change." The Earth Institute, Columbia University. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2009. <http://www.earth.columbia.edu/articles/view/2228>.

- ^ Climate Change and Texas (United States Environmental Protection Agency).

- ^ http://www.climateark.org/shared/reader/welcome.aspx?linkid=88481

- ^ "Impacts of Climate Change on Washington's Economy". Washington Department of Ecology. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ "Impacts of Climate Change on Washington's Economy" (PDF). Washington Economic Steering Committee, November 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

External links

- Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States edited by Tom Karl National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Asheville, North Carolina, Jerry Melillo Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Thomas Peterson National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Asheville, North Carolin, and Susan Joy Hassol Climate Communication, Basalt, Colorado. Summarizes the science of climate change and impacts on the United States, for the public and policymakers. ISBN 978-0-521-14407-0

- United States Environmental Protection Agency - climate change page

- Fourth U.S. Climate Action Report to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- U.S. Climate Report Details Energy, Agriculture Harm

- "Personal Emissions Calculator - Climate Change - What You Can Do". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2007-07-07.