Progesterone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Crinone, Endometrin |

| Other names | 4-pregnene-3,20-dione |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604017 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, implant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | prolonged absorption, half-life approx 25-50 hours |

| Protein binding | 96%-99% |

| Metabolism | hepatic to pregnanediols and pregnanolones |

| Elimination half-life | 34.8-55.13 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.318 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.46 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | [α]D |

| Melting point | 126 °C (259 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

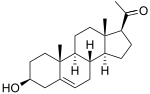

Progesterone also known as P4 (pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione) is a C-21 steroid hormone involved in the female menstrual cycle, pregnancy (supports gestation) and embryogenesis of humans and other species. Progesterone belongs to a class of hormones called progestogens, and is the major naturally occurring human progestogen.

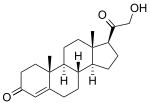

Progesterone is commonly manufactured from the yam family, Dioscorea. Dioscorea produces large amounts of a steroid called diosgenin, which can be converted into progesterone in the laboratory.

Chemistry

Progesterone was independently discovered by four research groups.[2][3][4][5]

Willard Myron Allen co-discovered progesterone with his anatomy professor George Washington Corner at the University of Rochester Medical School in 1933. Allen first determined its melting point, molecular weight, and partial molecular structure. He also gave it the name Progesterone derived from Progestational Steroidal ketone.[6]

Like other steroids, progesterone consists of four interconnected cyclic hydrocarbons. Progesterone contains ketone and oxygenated functional groups, as well as two methyl branches. Like all steroid hormones, it is hydrophobic.

Sources

Animal

Progesterone is produced in the ovaries (by the corpus luteum), the adrenal glands (near the kidney), and, during pregnancy, in the placenta. Progesterone is also stored in adipose (fat) tissue.

In humans, increasing amounts of progesterone are produced during pregnancy:

- At first, the source is the corpus luteum that has been "rescued" by the presence of human chorionic gonadotropins (hCG) from the conceptus.

- However, after the 8th week, production of progesterone shifts to the placenta. The placenta utilizes maternal cholesterol as the initial substrate, and most of the produced progesterone enters the maternal circulation, but some is picked up by the fetal circulation and used as substrate for fetal corticosteroids. At term the placenta produces about 250 mg progesterone per day.

- An additional source of progesterone is milk products. After consumption of milk products the level of bioavailable progesterone goes up.[7]

Plants

In at least one plant, Juglans regia, progesterone has been detected.[8] In addition, progesterone-like steroids are found in Dioscorea mexicana. Dioscorea mexicana is a plant that is part of the yam family native to Mexico.[9] It contains a steroid called diosgenin that is taken from the plant and is converted into progesterone.[10] Diosgenin and progesterone are found in other Dioscorea species as well.

Another plant that contains substances readily convertible to progesterone is Dioscorea pseudojaponica native to Taiwan. Research has shown that the Taiwanese yam contains saponins — steroids that can be converted to diosgenin and thence to progesterone.[11]

Many other Dioscorea species of the yam family contain steroidal substances from which progesterone can be produced. Among the more notable of these are Dioscorea villosa and Dioscorea polygonoides. One study showed that the Dioscorea villosa contains 3.5% diosgenin.[12] Dioscorea polygonoides has been found to contain 2.64% diosgenin as shown by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.[13] Many of the Dioscorea species that originate from the yam family grow in countries that have tropical and subtropical climates.[14]

Synthesis

Biosynthesis

Bottom: Progesterone is important for aldosterone (mineralocorticoid) synthesis, as 17-hydroxyprogesterone is for cortisol (glucocorticoid), and androstenedione for sex steroids.

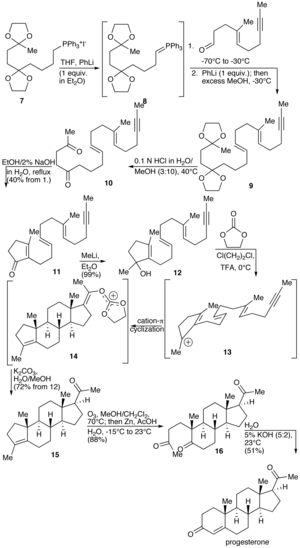

In mammals, progesterone (6), like all other steroid hormones, is synthesized from pregnenolone (3), which in turn is derived from cholesterol (1) (see the upper half of the figure to the right).

Cholesterol (1) undergoes double oxidation to produce 20,22-dihydroxycholesterol (2). This vicinal diol is then further oxidized with loss of the side chain starting at position C-22 to produce pregnenolone (3). This reaction is catalyzed by cytochrome P450scc. The conversion of pregnenolone to progesterone takes place in two steps. First, the 3-hydroxyl group is oxidized to a keto group (4) and second, the double bond is moved to C-4, from C-5 through a keto/enol tautomerization reaction.[15] This reaction is catalyzed by 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta(5)-delta(4)isomerase.

Progesterone in turn (see lower half of figure to the right) is the precursor of the mineralocorticoid aldosterone, and after conversion to 17-hydroxyprogesterone (another natural progestogen) of cortisol and androstenedione. Androstenedione can be converted to testosterone, estrone and estradiol.

Pregenolone and progesterone can also be synthesized by yeast.[16]

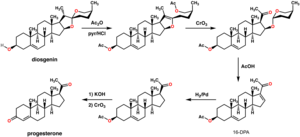

Laboratory

An economical semisynthesis of progesterone from the plant steroid diosgenin isolated from yams was developed by Russell Marker in 1940 for the Parke-Davis pharmaceutical company (see figure to the right).[17] This synthesis is known as the Marker degradation. Additional semisyntheses of progesterone have also been reported starting from a variety of steroids. For the example, cortisone can be simultaneously deoxygenated at the C-17 and C-21 position by treatment with iodotrimethylsilane in chloroform to produce 11-keto-progesterone (ketogestin), which in turn can be reduced at position-11 to yield progesterone.[18]

A total synthesis of progesterone was reported in 1971 by W.S. Johnson (see figure to the right).[19] The synthesis begins with reacting the phosphonium salt 7 with phenyl lithium to produce the phosphonium ylide 8. The ylide 8 is reacted with an aldehyde to produce the alkene 9. The ketal protecting groups of 9 are hydrolyzed to produce the diketone 10, which in turn is cyclized to form the cyclopentenone 11. The ketone of 11 is reacted with methyl lithium to yield the tertiary alcohol 12, which in turn is treated with acid to produce the tertiary cation 13. The key step of the synthesis is the π-cation cyclization of 13 in which the B-, C-, and D-rings of the steroid are simultaneously formed to produce 14. This step resembles the cationic cyclization reaction used in the biosynthesis of steroids and hence is referred to as biomimetic. In the next step the enol orthoester is hydrolyzed to produce the ketone 15. The cyclopentene A-ring is then opened by oxidizing with ozone to produce 16. Finally, the diketone 17 undergoes an intramolecular aldol condensation by treating with aqueous potassium hydroxide to produce progesterone.[19]

Levels

In women, progesterone levels are relatively low during the preovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, rise after ovulation, and are elevated during the luteal phase, as shown in diagram below. Progesterone levels tend to be < 2 ng/ml prior to ovulation, and > 5 ng/ml after ovulation. If pregnancy occurs, human chorionic gonadotropin is released maintaining the corpus leuteum allowing it to maintain levels of progesterone. At around 12 weeks the placenta begins to produce progesterone in place of the corpus leuteum, this process is named the luteal-placental shift. After the luteal-placental shift progesterone levels start to rise further and may reach 100-200 ng/ml at term. Whether a decrease in progesterone levels is critical for the initiation of labor has been argued and may be species-specific. After delivery of the placenta and during lactation, progesterone levels are very low.

Progesterone levels are relatively low in children and postmenopausal women.[20] Adult males have levels similar to those in women during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

| Person type | Reference range for blood test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit | |

| Female - menstrual cycle | (see diagram below) | ||

| Female - postmenopausal | <0.2[21] | 1[21] | ng/mL |

| <0,6[22] | 3[22] | nmol/L | |

| Female on oral contraceptives | 0.34[21] | 0.92[21] | ng/mL |

| 1.1[22] | 2.9[22] | nmol/L | |

| Males ≥16 years | 0.27[21] | 0.9[21] | ng/mL |

| 0.86[22] | 2.9[22] | nmol/L | |

| Female or male 1–9 years | 0.1[21] | 4.1[21] or 4.5[21] | ng/mL |

| 0.3[22] | 13[22] | nmol/L | |

- The ranges denoted By biological stage may be used in closely monitored menstrual cycles in regard to other markers of its biological progression, with the time scale being compressed or stretched to how much faster or slower, respectively, the cycle progresses compared to an average cycle.

- The ranges denoted Inter-cycle variability are more appropriate to use in non-monitored cycles with only the beginning of menstruation known, but where the woman accurately knows her average cycle lengths and time of ovulation, and that they are somewhat averagely regular, with the time scale being compressed or stretched to how much a woman's average cycle length is shorter or longer, respectively, than the average of the population.

- The ranges denoted Inter-woman variability are more appropriate to use when the average cycle lengths and time of ovulation are unknown, but only the beginning of menstruation is given.

Effects

Progesterone exerts its primary action through the intracellular progesterone receptor although a distinct, membrane bound progesterone receptor has also been postulated.[24][25] In addition, progesterone is a highly potent antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR, the receptor for aldosterone and other mineralocorticosteroids). It prevents MR activation by binding to this receptor with an affinity exceeding even those of aldosterone and other corticosteroids such as cortisol and corticosterone.[26]

Progesterone has a number of physiological effects that are amplified in the presence of estrogen. Estrogen through estrogen receptors upregulates the expression of progesterone receptors.[27] Also, elevated levels of progesterone potently reduce the sodium-retaining activity of aldosterone, resulting in natriuresis and a reduction in extracellular fluid volume. Progesterone withdrawal, on the other hand, is associated with a temporary increase in sodium retention (reduced natriuresis, with an increase in extracellular fluid volume) due to the compensatory increase in aldosterone production, which combats the blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor by the previously elevated level of progesterone.[28]

Reproductive system

Progesterone has key effects via non-genomic signalling on human sperm as they migrate through the female tract before fertilization occurs, though the receptor(s) as yet remain unidentified.[29] Detailed characterisation of the events occurring in sperm in response to progesterone has elucidated certain events including intracellular calcium transients and maintained changes,[30] slow calcium oscillations,[31] now thought to possibly regulate motility.[32] Interestingly progesterone has also been shown to demonstrate effects on octopus spermatozoa.[33]

Progesterone modulates the activity of CatSper (cation channels of sperm) voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Since eggs release progesterone, sperm may use progesterone as a homing signal to swim toward eggs (chemotaxis). Hence substances that block the progesterone binding site on CatSper channels could potentially be used in male contraception.[34][35]

Progesterone is sometimes called the "hormone of pregnancy",[36] and it has many roles relating to the development of the fetus:

- Progesterone converts the endometrium to its secretory stage to prepare the uterus for implantation. At the same time progesterone affects the vaginal epithelium and cervical mucus, making it thick and impenetrable to sperm. If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone levels will decrease, leading, in the human, to menstruation. Normal menstrual bleeding is progesterone-withdrawal bleeding. If ovulation does not occur and the corpus luteum does not develop, levels of progesterone may be low, leading to anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

- During implantation and gestation, progesterone appears to decrease the maternal immune response to allow for the acceptance of the pregnancy.

- Progesterone decreases contractility of the uterine smooth muscle.[36]

- In addition progesterone inhibits lactation during pregnancy. The fall in progesterone levels following delivery is one of the triggers for milk production.

- A drop in progesterone levels is possibly one step that facilitates the onset of labor.

The fetus metabolizes placental progesterone in the production of adrenal steroids.

Nervous system

Progesterone, like pregnenolone and dehydroepiandrosterone, belongs to the group of neurosteroids. It can be synthesized within the central nervous system and also serves as a precursor to another major neurosteroid, allopregnanolone.

Neurosteroids affect synaptic functioning, are neuroprotective, and affect myelination.[37] They are investigated for their potential to improve memory and cognitive ability. Progesterone affects regulation of apoptotic genes.

Its effect as a neurosteroid works predominantly through the GSK-3 beta pathway, as an inhibitor. (Other GSK-3 beta inhibitors include bipolar mood stabilizers, lithium and valproic acid.)

Other syndromes

- It raises epidermal growth factor-1 levels, a factor often used to induce proliferation, and used to sustain cultures, of stem cells.

- It increases core temperature (thermogenic function) during ovulation.[38]

- It reduces spasm and relaxes smooth muscle. Bronchi are widened and mucus regulated. (Progesterone receptors are widely present in submucosal tissue.)

- It acts as an antiinflammatory agent and regulates the immune response.

- It reduces gall-bladder activity.[39]

- It normalizes blood clotting and vascular tone, zinc and copper levels, cell oxygen levels, and use of fat stores for energy.

- It may affect gum health, increasing risk of gingivitis (gum inflammation) and tooth decay.

- It appears to prevent endometrial cancer (involving the uterine lining) by regulating the effects of estrogen.

Adverse effects

The convenient pill form of "progesterone" (whether it is actually progesterone, or is instead a synthetic, patented progestin), needs to be taken at unnaturally high doses; and, this can have a dramatic health impact. For example, 400 mg can cause increased fluid retention, which may result in epilepsy, migraine, asthma, cardiac or renal dysfunction. Blood clots that can result in strokes and heart attacks, which may lead to death or long-term disability, may develop; pulmonary embolus or breast cancer can also develop as a result of [current practices in] progesterone therapy. [High-dose] progesterone is associated with an increased risk of thrombotic disorders such as thrombophlebitis, cerebrovascular disorders, pulmonary embolism, and retinal thrombosis.[40]

Common adverse effects include cramps, abdominal pain, skeletal pain, perineal pain, headache, arthralgia, constipation, dyspareunia, nocturia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, breast enlargement, joint pain, flatulence, hot flushes, decreased libido, thirst, increased appetite, nervousness, drowsiness, excessive urination at night. Psychiatric effects including depression, mood swings, emotional instability, aggression, abnormal crying, insomnia, forgetfulness, sleep disorders.[40]

Less frequent adverse effects that may occur include allergy, anemia, bloating, fatigue, tremor, urticaria, pain, conjunctivitis, dizziness, vomiting, myalgia, back pain, breast pain, genital itching, genital yeast infection, upper respiratory tract infection, cystitis, dysuria, asthenia, xerophthalmia, syncope, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual tension, gastritis, urinary tract infection, vaginal discharge, pharyngitis, sweating, hyperventilation, vaginal dryness, dyspnea, fever, edema, flu-like symptoms, dry mouth, rhinitis, leg pain, skin discoloration, skin disorders, seborrhea, sinusitis, acne.[40]

Current research suggests that progesterone plays an important role in the signaling of insulin release and pancreatic function, and may affect the susceptibility to diabetes.[41] It has been shown that women with high levels of progesterone during pregnancy are more likely to develop glucose abnormalities.[42]

Medical applications

The use of progesterone and its analogues have many medical applications, both to address acute situations and to address the long-term decline of natural progesterone levels. Because of the poor bioavailability of progesterone when taken orally, many synthetic progestins have been designed with improved oral bioavailability.[43] Progesterone was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as vaginal gel on July 31, 1997,[44] an oral capsule on May 14, 1998[45] in an injection form on April 25, 2001[46] and as a vaginal insert on June 21, 2007.[47] In Italy and Spain, Progesterone is sold under the trademark Progeffik.

Bioavailability

The route of administration impacts the effect of the drug. Given orally, progesterone has a wide person-to-person variability in absorption and bioavailability while synthetic progestins are rapidly absorbed with a longer half-life than progesterone and maintain stable levels in the blood.[48]

Progesterone does not dissolve in water and is poorly absorbed when taken orally unless micronized in oil. Products are often sold as capsules containing micronised progesterone in oil. Progesterone can also be administered through vaginal or rectal suppositories or pessaries, transdermally through a gel or cream,[49] or via injection (though the latter has a short half-life requiring daily administration).

"Natural progesterone" products derived from yams do not require a prescription, but there is no evidence that the human body can convert its active ingredient (diosgenin, the plant steroid that is chemically converted to produce progesterone industrially[17]) into progesterone.[50][51]

Specific uses

- Progesterone is used to support pregnancy in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) cycles such as In-vitro Fertilization (IVF). While daily intramuscular injections of progesterone-in-oil (PIO) have been the standard route of administration, PIO injections are not FDA-approved for use in pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis showed that the intravaginal route with an appropriate dose and dosing frequency is equivalent to daily intramuscular injections.[52] In addition, a recent case-matched study comparing vaginal progesterone with PIO injections showed that live birth rates were nearly identical with both methods.[53]

- Progesterone is used to control persistent anovulatory bleeding. It is also used to prepare uterine lining in infertility therapy and to support early pregnancy. Patients with recurrent pregnancy loss due to inadequate progesterone production may receive progesterone.

- Progesterone is also used in nonpregnant women with a delayed menstruation of one or more weeks, in order to allow the thickened endometrial lining to slough off. This process is termed a progesterone withdrawal bleed. The progesterone is taken orally for a short time (usually one week), after which the progesterone is discontinued and bleeding should occur.

- Progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in treating multiple sclerosis, since the characteristic deterioration of nerve myelin insulation halts during pregnancy, when progesterone levels are raised; deterioration commences again when the levels drop.

- Vaginally dosed progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in preventing preterm birth in women at risk for preterm birth. The initial study by Fonseca suggested that vaginal progesterone could prevent preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth.[54] According to a recent study, women with a short cervix that received hormonal treatment with a progesterone gel had their risk of prematurely giving birth reduced. The hormone treatment was administered vaginally every day during the second half of a pregnancy.[55] A subsequent and larger study showed that vaginal progesterone was no better than placebo in preventing recurrent preterm birth in women with a history of a previous preterm birth,[56] but a planned secondary analysis of the data in this trial showed that women with a short cervix at baseline in the trial had benefit in two ways: a reduction in births less than 32 weeks and a reduction in both the frequency and the time their babies were in intensive care.[57] In another trial, vaginal progesterone was shown to be better than placebo in reducing preterm birth prior to 34 weeks in women with an extremely short cervix at baseline.[58] An editorial by Roberto Romero discusses the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment.[59] A meta-analysis published in 2011 found that vaginal progesterone cut the risk of premature births by 42 percent in women with short cervixes.[60] The meta-analysis, which pooled published results of five large clinical trials, also found that the treatment cut the rate of breathing problems and reduced the need for placing a baby on a ventilator.[61]

- Progesterone also has a role in skin elasticity and bone strength, in respiration, in nerve tissue and in female sexuality, and the presence of progesterone receptors in certain muscle and fat tissue may hint at a role in sexually-dimorphic proportions of those.[62]

- Progesterone receptor antagonists, or selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRM)s, such as RU-486 (Mifepristone), can be used to prevent conception or induce medical abortions (Note that methods of hormonal contraception do not contain progesterone but a progestin).

- Progesterone may affect male behavior.[63]

- Progesterone is starting to be used in the treatment of the skin condition hidradenitis suppurativa.[citation needed]

Aging

Since most progesterone in males is created during testicular production of testosterone, and most in females by the ovaries, the shutting down (whether by natural or chemical means), or removal, of those inevitably causes a considerable reduction in progesterone levels. Previous concentration upon the role of progestagens (progesterone and molecules with similar effects) in female reproduction, when progesterone was simply considered a "female hormone", obscured the significance of progesterone elsewhere in both sexes.

The tendency for progesterone to have a regulatory effect, the presence of progesterone receptors in many types of body tissue, and the pattern of deterioration (or tumor formation) in many of those increasing in later years when progesterone levels have dropped, is prompting widespread research into the potential value of maintaining progesterone levels in both males and females.

Brain damage

Previous studies have shown that progesterone supports the normal development of neurons in the brain, and that the hormone has a protective effect on damaged brain tissue. It has been observed in animal models that females have reduced susceptibility to traumatic brain injury and this protective effect has been hypothesized to be caused by increased circulating levels of estrogen and progesterone in females.[64] A number of additional animal studies have confirmed that progesterone has neuroprotective effects when administered shortly after traumatic brain injury.[65] Encouraging results have also been reported in human clinical trials.[66][67]

The mechanism of progesterone protective effects may be the reduction of inflammation that follows brain trauma.[68]

See also

- Willard Myron Allen

- Endometrin

- AKR1C1 - the enzyme that deactivates progesterone

- Percy Julian

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Allen WM (1935). "The isolation of crystalline progestin". Science. 82 (2118): 89–93. doi:10.1126/science.082.2118.89. PMID 17747122.

- ^ Butenandt A, Westphal U (1934). "Zur Isolierung und Charakterisierung des Corpusluteum-Hormons". Berichte Deu0tsche chemische Gesellschaft. 67 (8): 1440–1442. doi:10.1002/cber.19340670831.

- ^ Hartmann M, Wettstein A (1934). "Ein krystallisiertes Hormon aus Corpus luteum". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 17: 878–882. doi:10.1002/hlca.193401701111.

- ^ Slotta KH, Ruschig H, Fels E (1934). "Reindarstellung der Hormone aus dem Corpusluteum". Berichte Deutsche chemische Gesellschaft. 67 (7): 1270–1273. doi:10.1002/cber.19340670729.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allen WM (1970). "Progesterone: how did the name originate?". South. Med. J. 63 (10): 1151–5. doi:10.1097/00007611-197010000-00012. PMID 4922128.

- ^ Goodson III WH, Handagama P, Moore II DH, Dairkee S (2007-12-13). "Milk products are a source of dietary progesterone". 30th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. pp. abstract # 2028. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pauli GF, Friesen JB, Gödecke T, Farnsworth NR, Glodny B (2010). "Occurrence of Progesterone and Related Animal Steroids in Two Higher Plants". J Nat Prod. 73 (3): 338–45. doi:10.1021/np9007415. PMID 20108949.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Applezweig N (1969). "Steroids". Chem Week. 104: 57–72. PMID 12255132.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Noguchi E, Fujiwara Y, Matsushita S, Ikeda T, Ono M, Nohara T (2006). "Metabolism of tomato steroidal glycosides in humans". Chem. Pharm. Bull. 54 (9): 1312–4. doi:10.1248/cpb.54.1312. PMID 16946542.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yang DJ, Lu TJ, Hwang LS (2003). "Isolation and identification of steroidal saponins in Taiwanese yam cultivar (Dioscorea pseudojaponica Yamamoto)". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (22): 6438–44. doi:10.1021/jf030390j. PMID 14558759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hooker E (2004). "Final report of the amended safety assessment of Dioscorea Villosa (Wild Yam) root extract". Int. J. Toxicol. 23 Suppl 2: 49–54. doi:10.1080/10915810490499055. PMID 15513824.

- ^ Niño J, Jiménez DA, Mosquera OM, Correa YM (2007). "Diosgenin quantification by HPLC in a Dioscorea polygonoides tuber collection from colombian flora". Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 18 (5): 1073–1076. doi:10.1590/S0103-50532007000500030.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Myoda T, Nagai T, Nagashima T (2005). Properties of starches in yam (Dioscorea spp.) tuber. pp. 105–114. ISBN 81-308-0003-9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dewick, Paul M. (2002). Medicinal natural products: a biosynthetic approach. New York: Wiley. p. 244. ISBN 0-471-49641-3.

- ^ Duport C, Spagnoli R, Degryse E, Pompon D (1998). "Self-sufficient biosynthesis of pregnenolone and progesterone in engineered yeast". Nat. Biotechnol. 16 (2): 186–9. doi:10.1038/nbt0298-186. PMID 9487528.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Marker RE, Krueger J (1940). "Sterols. CXII. Sapogenins. XLI. The Preparation of Trillin and its Conversion to Progesterone". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62 (12): 3349–3350. doi:10.1021/ja01869a023.

- ^ Numazawa M, Nagaoka M, Kunitama Y (1986). "Regiospecific deoxygenation of the dihydroxyacetone moiety at C-17 of corticoid steroids with iodotrimethylsilane". Chem. Pharm. Bull. 34 (9): 3722–6. doi:10.1248/cpb.34.3722. PMID 3815593.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Johnson WS, Gravestock MB, McCarry BE (1971). "Acetylenic bond participation in biogenetic-like olefinic cyclizations. II. Synthesis of dl-progesterone". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93 (17): 4332–4. doi:10.1021/ja00746a062. PMID 5131151.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NIH Clinical Center (2004-08-16). "Progesterone Historical Reference Ranges". United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Progesterone Reference Ranges, Performed at the Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD, 03Feb09

- ^ a b c d e f g h Converted from mass values using molar mass of 314.46 g/mol

- ^ References and further description of values are given in image page in Wikimedia Commons at Commons:File:Progesterone during menstrual cycle.png.

- ^ Luconi M, Bonaccorsi L, Maggi M, Pecchioli P, Krausz C, Forti G, Baldi E (1998). "Identification and characterization of functional nongenomic progesterone receptors on human sperm membrane". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 83 (3): 877–85. doi:10.1210/jc.83.3.877. PMID 9506743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jang S, Yi LS (2005). "Identification of a 71 kDa protein as a putative non-genomic membrane progesterone receptor in boar spermatozoa". J. Endocrinol. 184 (2): 417–25. doi:10.1677/joe.1.05607. PMID 15684349.

- ^ Rupprecht R, Reul JM, van Steensel B, Spengler D, Söder M, Berning B, Holsboer F, Damm K (1993). "Pharmacological and functional characterization of human mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor ligands". Eur J Pharmacol. 247 (2): 145–54. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(93)90072-H. PMID 8282004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P (1990). "Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B". EMBO J. 9 (5): 1603–14. PMC 551856. PMID 2328727.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Landau RL, Bergenstal DM, Lugibihl K, Kascht ME. (1955). "The metabolic effects of progesterone in man". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 15 (10): 1194–215. doi:10.1210/jcem-15-10-1194. PMID 13263410.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Correia JN, Conner SJ, Kirkman-Brown JC (2007). "Non-genomic steroid actions in human spermatozoa. "Persistent tickling from a laden environment"". Semin. Reprod. Med. 25 (3): 208–19. doi:10.1055/s-2007-973433. PMID 17447210.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirkman-Brown JC, Bray C, Stewart PM, Barratt CL, Publicover SJ (2000). "Biphasic elevation of [Ca(2+)](i) in individual human spermatozoa exposed to progesterone". Developmental Biology. 222 (2): 326–35. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.9729. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 10837122.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirkman-Brown JC, Barratt CL, Publicover SJ (2004). "Slow calcium oscillations in human spermatozoa". The Biochemical Journal. 378 (Pt 3): 827–32. doi:10.1042/BJ20031368. PMC 1223996. PMID 14606954.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harper CV, Barratt CL, Publicover SJ (2004). "Stimulation of human spermatozoa with progesterone gradients to simulate approach to the oocyte. Induction of [Ca(2+)](i) oscillations and cyclical transitions in flagellar beating". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (44): 46315–25. doi:10.1074/jbc.M401194200. PMID 15322137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tosti E, Di Cosmo A, Cuomo A, Di Cristo C, Gragnaniello G (2001). "Progesterone induces activation in Octopus vulgaris spermatozoa". Mol. Reprod. Dev. 59 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1002/mrd.1011. PMID 11335951.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Strünker T, Goodwin N, Brenker C, Kashikar ND, Weyand I, Seifert R, Kaupp UB (2011). "The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx in human sperm". Nature. 471 (7338): 382–6. doi:10.1038/nature09769. PMID 21412338.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lishko PV, Botchkina IL, Kirichok Y (2011). "Progesterone activates the principal Ca2+ channel of human sperm". Nature. 471 (7338): 387–91. doi:10.1038/nature09767. PMID 21412339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bowen R (2000-08-06). "Placental Hormones". Retrieved 2008-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Robert F; et al. (2004). "Local synthesis and dual actions of progesterone in the nervous system: neuroprotection and myelination". Growth Horm. IGF Res. 14 Suppl A: S18–33. doi:10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.007. PMID 15135772.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Template:GeorgiaPhysiology

- ^ Hould FS, Fried GM, Fazekas AG, Tremblay S, Mersereau WA (1988). "Progesterone receptors regulate gallbladder motility". J. Surg. Res. 45 (6): 505–12. doi:10.1016/0022-4804(88)90137-0. PMID 3184927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Columbia Laboratories, Inc. (2004). "Prometrium(progesterone)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Picard F, Wanatabe M, Schoonjans K, Lydon J, O'Malley BW, Auwerx J (2002). "Progesterone receptor knockout mice have an improved glucose homeostasis secondary to beta -cell proliferation" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brănişteanu DD, Mathieu C (2003). "Progesterone in gestational diabetes mellitus: guilty or not guilty?".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Huber J, Pasqualini JR, Schweppe KW, Thijssen JH (2008). "Classification and pharmacology of progestins" (PDF). Maturitas. 61 (1–2): 171–80. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.09.014. PMID 19434889.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 020701". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 019781". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 075906". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 022057". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14670641 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 14670641instead. - ^ Lark, Susan (1999). Making the Estrogen Decision. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 22. ISBN 0879836962, 9780879836962.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Zava DT, Dollbaum CM, Blen M (1998). "Estrogen and progestin bioactivity of foods, herbs, and spices". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 217 (3): 369–78. PMID 9492350.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Komesaroff PA, Black CV, Cable V, Sudhir K (2001). "Effects of wild yam extract on menopausal symptoms, lipids and sex hormones in healthy menopausal women". Climacteric. 4 (2): 144–50. doi:10.1080/713605087. PMID 11428178.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zarutskiea PW, Phillips JA (2007). "Re-analysis of vaginal progesterone as luteal phase support (LPS) in assisted reproduction (ART) cycles". Fertility and Sterility. 88 (supplement 1): S113. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.365.

- ^ Khan N, Richter KS, Blake EJ, et al. Case-matched comparison of intramuscular versus vaginal progesterone for luteal phase support after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Presented at: 55th Annual Meeting of the Pacific Coast Reproductive Society; April 18–22, 2007; Rancho Mirage, CA.

- ^ da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M (2003). "Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (2): 419–24. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.41. PMID 12592250.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harris, Gardiner. "Hormone Is Said to Cut Risk of Premature Birth". New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Defranco EA, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schackis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (2007). "Progesterone vaginal gel for the reduction of recurrent preterm birth: primary results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 30 (5): 687–96. doi:10.1002/uog.5158. PMID 17899572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeFranco EA, O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schakis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (2007). "Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 30 (5): 697–705. doi:10.1002/uog.5159. PMID 17899571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH (2007). "Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (5): 462–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067815. PMID 17671254.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Romero R (2007). "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 30 (5): 675–86. doi:10.1002/uog.5174. PMID 17899585.

- ^ Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, Fusey S, Baxter JK, Khandelwal M, Vijayaraghavan J, Trivedi Y, Soma-Pillay P, Sambarey P, Dayal A, Potapov V, O'Brien J, Astakhov V, Yuzko O, Kinzler W, Dattel B, Sehdev H, Mazheika L, Manchulenko D, Gervasi MT, Sullivan L, Conde-Agudelo A, Phillips JA, Creasy GW (2011). "Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 38 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1002/uog.9017. PMID 21472815.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Progesterone helps cut risk of pre-term birth". Women's health. msnbc.com. 2011-12-14. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ^ Sriram, D (2007). Medicinal Chemistry. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley India Pvt. Ltd. p. 432. ISBN 81-317-0031-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Schneider JS, Stone MK, Wynne-Edwards KE, Horton TH, Lydon J, O'Malley B, Levine JE (2003). "Progesterone receptors mediate male aggression toward infants". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (5): 2951–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0130100100. PMC 151447. PMID 12601162.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roof RL, Hall ED (2000). "Gender differences in acute CNS trauma and stroke: neuroprotective effects of estrogen and progesterone". J. Neurotrauma. 17 (5): 367–88. doi:10.1089/neu.2000.17.367. PMID 10833057.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gibson CL, Gray LJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP (2008). "Progesterone for the treatment of experimental brain injury; a systematic review". Brain. 131 (Pt 2): 318–28. doi:10.1093/brain/awm183. PMID 17715141.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, Salomone JP, Dent LL, Harris OA, Ander DS, Lowery DW, Patel MM, Denson DD, Gordon AB, Wald MM, Gupta S, Hoffman SW, Stein DG (2007). "ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury". Ann Emerg Med. 49 (4): 391–402, 402.e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. PMID 17011666.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z (2008). "Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial". Crit Care. 12 (2): R61. doi:10.1186/cc6887. PMC 2447617. PMID 18447940.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Pan DS, Liu WG, Yang XF, Cao F (2007). "Inhibitory effect of progesterone on inflammatory factors after experimental traumatic brain injury". Biomed. Environ. Sci. 20 (5): 432–8. PMID 18188998.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Additional images

External links

- Progesterone at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Kimball JW (2007-05-27). "Progesterone". Kimball's Biology Pages. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Progesterone Resource Center". PMS, Menopause, and Progesterone Resource Center. Oasis Advanced Wellness, Inc. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - General discussion document on Progesterone, its uses and applications