United States Grand Prix

| Circuit of the Americas | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 41 |

| First held | 1908 |

| Last held | 2007 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 5.5 km (3.4 miles) |

| Race length | TBD km (TBD miles) |

| Last race (2007) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

The United States Grand Prix is a motor race which has been run on and off since 1908, when it was known as the American Grand Prize. The race later became part of the Formula One World Championship. Over 41 editions, the race has been held at nine locations, most recently in 2007 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The race is due to return to the F1 calendar in the 2012 season at Austin, Texas on 18 November 2012.

History

Origins

Inspired by the Gordon Bennett Cup and Circuit des Ardennes races he had competed in, William Kissam Vanderbilt founded a series of road races in the United States to showcase American road racing to the world. The Vanderbilt Cup soon became an institution on New York's Long Island, attracting American and European competitors alike. However, the race was plagued by crowd control problems, which led to spectator deaths and injuries, and the cancellation of the 1907 event. Upon its return for 1908, the American Automobile Association did not adopt the new Grand Prix regulations agreed upon by the Association Internationale des Automobiles Clubs Reconnus (AIACR).[1][2] This led the rival Automobile Club of America, an enthusiats group with strong ties to Europe, to sponsor the American Grand Prize, using the Grand Prix rules.[3] The Savannah Automobile Club, who had staged a successful stock car race in the spring, won the rights to stage the event.[4]

The Grand Prize era (1908–1916)

The Savannah Automobile Club laid out a lengthened version of their stock car course, totaling 25.13 mi (40.44 km). Georgia Governor M. Hoke Smith authorized the use of convict labor to construct the circuit of oiled gravel. The Governor also sent state militia troops to augment local police patrols in keeping the crowd in check, hoping to avoid the pitfalls of the Vanderbilt Cup races.[5] The entry for the inaugural race featured 14 European and 6 American entires, including factory teams from Benz, Fiat, and Renault.[6] In the race, held on Thanksgiving Day, Ralph DePalma led early in his Fiat, before falling back with lubrication and tire problems. The race came down to a three-way battle between the Benz of Victor Hémery and the Fiats of Louis Wagner and Felice Nazzaro. Wagner won the race by the unprecedentedly close margin of 56 seconds.[7]

Despite the success of the Savannah event, it was decided that the 1909 race would be held on Long Island, in conjunction with the Vanderbilt Cup. However, only the Vanderbilt race was held, and the Grand Prize pushed back to the next year. After the 1910 Vanderbilt Cup saw more issues, including the deaths of 2 riding mechanics and several serious spectator injuries, the Grand Prize was cancelled once again. A last-minute request by the Savannah club saved the race for the year, but only gave one month to prepare the course. A shorter 17-mile (27 km) course was laid out, but due to the short notice, most European teams were not able to make the trip. The leading trio from 1908 did make it, and American David Bruce-Brown joined the Benz squad. Bruce-Brown won another incredibly tight race over teammate Hémery, this time by only 1.42 seconds.[8] The 1911 event returned to Savannah, and this time the Vanderbilt Cup came with it; the Cup and Grand Prize were to be held together until 1916. Despite the success of the events, public pressure started to amount on the organizers. The use of convict labor and the militia drew criticism, as did the nuisance of closing roads for the event.[9] Two accidents on the open roads in practice, one resulting in the death of Jay McNay, cast a shadow over the event. The American entries dominated the support events and ran well throughout the Grand Prize, after poor showings in past years, and once again Bruce-Brown triumphed, this time driving a Fiat.[10]

For 1912, Savannah succumbed to public pressure, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, won the bid for the race. A narrow, 7.88-mile (12.68 km) trapezoidal course was set up on the outskirts of the city, in Wauwatosa. As in 1911, tragedy struck in practice when David Bruce-Brown was killed after a puncture sent him off the road. On the final lap of the race, Ralph DePalma collided with eventual winner Caleb Bragg, seriously injuring DePalma and his mechanic, and ending any chance of a second race at Milwaukee.[11]

The Grand Prize was not held in 1913, after Long Island's bid was rejected, and Savannah refused to provide sufficient prize money. Oval racing on board tracks had taken off in the United States, to the detriment of road racing. For 1914, the Grand Prize and Vanderbilt Cup were staged in Santa Monica, California, on an 8.4-mile (13.5 km) course, with the start/finish straight along the Pacific Ocean. The field was primarily American entries (12, against 5 European entries), and the Americans dominated, with Eddie Pullen's Mercer winning by over 40 seconds.[12] In 1915, the race shifted to San Francisco, in conjunction with the Panama–Pacific International Exposition. With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, almost all of the drivers and cars were American, except for a few cars imported earlier. The 3.84-mile (6.18 km) course was set up around the Exposition grounds and nearby oval track with a boarded main straightaway. Heavy rain began two hours into the race, covering the circuit in mud from the extensive flower arrangements, and warping the main straight's boards. Dario Resta in a Peugeot cruised to a 7-minute victory, and followed up a week later by winning the Vanderbilt Cup.[13] For 1916, the Grand Prize returned to Santa Monica. The race would be a part of the AAA National Championship, which carried a 4.91-liter displacement limit. Although the limit for the Grand Prize was 7.37 liters, no large-displacement cars would enter. The race was the penultimate round of the championship, with Dario Resta leading Johnny Aitken after his Vanderbilt Cup win. However, both cars would be out before halfway. Although Aitken took over teammate Howdy Wilcox's car for the win, the AAA awarded points only to Wilcox, and Resta took the championship.[14][15]

Post-war decline and revival (1917-1957)

The Grand Prize was discontinued after the 1916 event. Between a lack of European participation due to World War I and the growing American interest in oval racing, road racing fell by the wayside. The two Santa Monica events were the only road races on the 1916 championship, and the aborted 1917 National Championship was slated to feature 8 events, all ovals and 6 of them board tracks.[16] The Vanderbilt Cup was revived in 1936 and 1937 and run to Grand Prix regulations, but the races were a commercial failure.

The Indianapolis 500 kept a connection to European racing, running to Grand Prix regulations between 1923 and 1930,[1] and from 1938 until 1953.[17] In the late 1920s, efforts were made to refer to the 500 as the American Grand Prize.[18] The Grand Prize trophy was awarded to the winner of the Indianapolis 500 between 1930[19] and 1936, when it was replaced by the Borg-Warner Trophy. The race was included in the World Championship from 1950 through 1960.

Riverside and Sebring (1958–1960)

Riverside International Raceway opened in Riverside, California, in 1957 and one of its first events was an SCCA National sports car race. For 1958, the race moved to the new, professional, USAC Road Racing Championship, and was billed as the "United States Grand Prix".[17][20] The race attracted over 50 cars and drivers from sports car series in the U.S. and Europe, as well as USAC and NASCAR. Chuck Daigh won in a Scarab, beating Dan Gurney's Ferrari in second place.[21][22]

Russian-born Alec Ulmann staged the first 12 Hours of Sebring in 1952, and it became a round of the World Sportscar Championship in 1953. Buoyed by the success of the 12 Hours, the Riverside sports car race and Formula Libre events at Watkins Glen and Lime Rock Park, Ulmann decided to stage a Formula One race at Sebring International Raceway in 1959. The race was billed as the "II United States Grand Prix",[23] cementing the Riverside race as a part of the Grand Prix's heritage. The race was originally scheduled for March 22, the day after the 12 Hour-race, but rescheduled for December 12, the final round of the season.[24] The race took place 3 months after the previous round at Monza. The starting grid included seven American drivers, but New Zealand's Bruce McLaren, in a Cooper, took his first win in F1 and was, at the time, the youngest driver ever to win a Grand Prix. McLaren took the lead on the last lap of the race when his team-mate, Jack Brabham, ran out of fuel. Brabham had to push his car over the line to finish fourth. By virtue of Ferrari's Tony Brooks finishing 3rd, Brabham and Cooper took the drivers' and constructor's championships.[25] Despite providing an exciting climax to the season, the race wasn't successful from the hosts' standpoint, as the promoters barely broke even; when prize money checks bounced, Charles Moran and Briggs Cunningham paid the money to save face for their country.[17]

Ulmann moved the race to the Riverside International Raceway in Riverside, California in 1960. Stirling Moss put on quite a show in his privately-entered Lotus by winning from the pole. However, while the driver's purse was enormous (as at Sebring), the event was no better received than the previous year's due to a lack of promotion, and proximity to the successful Times Grand Prix.[26] Again Moran and Cunningham would pay the prize money.[17]

Watkins Glen (1961–1980)

Through most of 1961, Ulmann was listed as the promoter of the USGP, and contacted organizers in Miami and Bill France of the Daytona International Speedway but was unable to reach agreements. In August, Watkins Glen promoter Cameron Argetsinger offered his 2.35-mile (3.78 km) circuit to the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States (ACCUS) to host the Grand Prix. Watkins Glen had hosted a series of Formula Libre events that attracted international entries. ACCUS accepted on August 28, leaving only 6 weeks to organize the event on October 8. Argetsinger assembled the field, but was unable to convince Scuderia Ferrari to make the trip, leaving Richie Ginther and recently-crowned World Champion Phil Hill out of their home Grand Prix.[17] Innes Ireland took a surprise win, his first and the first for Team Lotus. Dan Gurney's Porsche was second, and Tony Brooks was third in his final Grand Prix. Unlike the previous two races, the race was well attended (over 60,000) and turned a profit.[27] The race purse was paid in cash, a popular move with the teams after the previous two years' payment issues.[17]

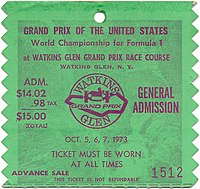

Over the next twenty years, the event became a tradition among the fans as loyal crowds gathered each autumn on the wooded hills of Upstate New York. It was one of the season's most popular events with the teams and drivers as well, receiving the Grand Prix Drivers' Association award for the best organized and best staged Grand Prix of the season in 1965, 1970, and 1971.[28] In 1971, the course was lengthened to 3.377 miles (5.435 km) with the addition of the "boot" section and the straightening of other sections, and also saw a new pitlane. The improvements cost nearly $2.5 million ($13 million in 2010 dollars).[29] Due to its position on the calendar near the end of the season, often either the final or penultimate round, championships were often decided before the event. In part to offset this, race organizers offered large sums of prize money; in 1969 the purse totaled $200,000 (with $50,000 for the winner),[30] and when in 1972 it was raised to $275,000, the Tyrrell team earned a record $100,000.[31]

The event saw highs, such as the only World Championship victory for BRM's H16 engine in 1966, and a 0.6-second winning margin in 1973 for Ronnie Peterson over James Hunt. Championships were clinched by the Brabham team in 1966, Jochen Rindt (posthumously) and Lotus in 1970, Lotus in 1973, Emerson Fittipaldi and McLaren in 1974, Nikki Lauda and Ferrari in 1976, and Lauda in 1977. The event also reached lows, with the deaths of François Cevert in 1973[32] and Helmut Koinigg in 1974, [33] and the politically-charged event of 1975.

By the late 1970s, the track had deteriorated from its earlier splendor. Drivers began complaining about the bumpy track surface, and the teams and press were concerned over facilities and rowdy fans.[34] The event was due to be cancelled for the 1980 season, but given a reprieve by FISA after promising to upgrade facilities over the winter.[35] After initially being given an April 13 date on the calendar, the race was moved to October 5.[36][37] Organizers were finally able to secure funding for circuit improvements in late August,[38] but still needed a $750,000 loan from FOCA to pay prize money and other expenses.[39] Alan Jones won the 1980 race for Williams, in what would prove to be the final USGP at the Glen. It was initially included on the 1981 calendar, but canceled after the debts could not be paid and government loans were denied.[39][40]

Other Grands Prix in the United States (1976-1988)

In 1976, the Long Beach Grand Prix became a Formula One event, making the United States the first nation since Italy in 1957 to hold two Grands Prix in the same season. The United States Grand Prix West, as it was called to distinguish from the United States Grand Prix East at Watkins Glen, was held until 1983, after which CART became the headliner series. The Caesars Palace Grand Prix was a non-starter in 1980, debuting in 1981; it would only last two years with Formula One, before CART took over the race for another two seasons. 1982 saw the inaugural Detroit Grand Prix, making 3 Formula One races in the United States that year. Detroit would last until 1988, after which it too became a CART event. A one-off Dallas Grand Prix was held in 1984, plagued by track problems exacerbated by extremely high temperatures.[41]

A new Grand Prix in the New York City area was announced for the 1983 season, to be held either at the Meadowlands Sports Complex, Meadow Lake in Flushing Meadows, or Mitchel Field in Hempstead, Long Island (on the same site as the 1936 and 1937 Vanderbilt Cups).[42][43] However, the race was first postponed and then canceled,[44] as CART started their own race at the Meadowlands, and titled it the "United States Grand Prix".[45]

Phoenix (1989–1991)

Plans to continue Formula One races in the Detroit area at the nearby Belle Isle Park did not materialize, and in 1989, Formula One moved to Phoenix, Arizona.[46] The Phoenix street circuit was laid out in downtown Phoenix and was unpopular with drivers and the local crowd; apocryphally, the 1990 event was outdrawn threefold by an ostrich race in the suburb of Chandler.[47][48][49]

The inaugural event in 1989 was held in June, with temperatures nearing 100 °F (38 °C). The race was moved to March, as the opening round of the season, for the next two years. The McLaren team dominated all three years, with Alain Prost winning in 1989 and Ayrton Senna in 1990 and 1991. After the 1991 race was attended by little more than 18,500 spectators,[50] Formula One left and did not return to the United States until 2000.

Indianapolis (2000–2007)

It was not until 2000 that another United States Grand Prix took place, this time at the legendary Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Indianapolis was rumored to have been considering a Formula One race since the USGP left Phoenix.[51] The 2.606-mile (4.194 km) infield road course uses about a mile of the oval, but in a clockwise direction. The crowd at the 2000 race was estimated at over 225,000, perhaps the largest ever in F1.[52] Michael Schumacher's win was his second of four straight to end the season as he overtook Mika Häkkinen for his third Championship. In 2001, the race took place less than three weeks after the events on 11 September 2001 in the US, and many teams and drivers featured special tributes to the USA on their cars and helmets. The 2002 edition was known for Schumacher and teammate Rubens Barrichello trading places near the finish line after Schumacher's failed bid to end the race into a dead heat with Barrichello. Held in September its first four years (in order to distance it from the "500" and NASCAR's Brickyard 400), the USGP at Indianapolis was moved to an early summer date in 2004. In 2005, problems with Michelin tires led to seven teams withdrawing from the race after the formation lap. Only the three teams (six cars) with Bridgestone tires started the 2005 United States Grand Prix, and the event was considered a farce.[53] Many commentators questioned whether a United States Grand Prix would be held in Indianapolis again, but the 2006 United States Grand Prix was held the next year, on 2 July 2006, without controversy.

On 12 July 2007, Formula One and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway announced that the 2007 U.S. Grand Prix would be the last one held at IMS for the foreseeable future, as both sides could not agree on the terms for the event.[54] It was thought that the race would return to Indianapolis for 2009 on the track configuration that was used for the 2008 race in the MotoGP championship.[55] Then-Indianapolis Motor Speedway CEO, Tony George, claimed that the USGP would not return to Indianapolis unless it made financial sense. Due to the expensive fees paid to host a grand prix, the race would require a title sponsor to be economically viable.[56] Ultimately, the United States Grand Prix was not on the Formula One calendar for 2009.

Austin (2012–)

In August 2009, Formula One president Bernie Ecclestone remarked that there was no immediate plan to return Formula One to the US, vowing "never to return" to Indianapolis.[57] Nevertheless, shortly before the first race of the 2010 season, Ecclestone continued to fuel speculation that a return to Indianapolis was not out of the question.[58] In March 2010, Ecclestone announced plans to bring a Formula One race to New York City for the 2012 season. Ecclestone was quoted as saying the race would take place across the Hudson River in New Jersey, with the Manhattan skyline overlooking the circuit.[59] In May 2010, plans emerged for a circuit to be built in Jersey City's Liberty State Park,[60][61] but those plans were abandoned shortly thereafter.[62] A race in West New York and Weehawken was later announced in October 2011. In May 2010, it was announced that Monticello Motor Club – a circuit complex modeled on a private country club near Monticello – had submitted a bid for the rights to host the race.[63]

On 25 May 2010, Austin, Texas, was awarded the race on a ten-year contract, as Ecclestone and event promoter Full Throttle Productions agreed to a deal beginning in 2012. The event will be held on a purpose-built new track.[64] The race promoter confirmed that over 800 acres (320 ha) to the east of the city had been purchased, and that Hermann Tilke, Formula One's resident circuit design expert, has been commissioned to design the layout and infrastructure.[65] In July 2010, promoter Tavo Hellmund promised that the circuit would be one of the "most challenging and spectacular in the world" and that it would include a selection of corner sequences inspired by "the very best circuits" in the world.[66] Construction on the new Circuit of the Americas began on December 31 2010,[67] and is due to be complete by June 2012.[68]

On 15 November 2011 it was reported that construction of the circuit had been temporarily halted as the owners had not yet been awarded the contract to stage the race in 2012,[69] following reports that Bernie Ecclestone had cast doubt on the race taking place.[70][71][72] After much speculation of the race being cancelled, the Formula 1 United States Grand Prix was confirmed to be held at the Circuit of the Americas in Austin on the original scheduled date in 2012. [73]

Winners

Events which were not part of the Formula One World Championship are indicated by a pink background.

Notes:

- From 1908–1916, the race was named the American Grand Prize.

Multiple winners (drivers)

Embolded drivers are still competing in the Formula One championship

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| # Wins | Driver | Years Won |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 | |

| 3 | 1963, 1964, 1965 | |

| 1962, 1966, 1967 | ||

| 2 | 1910, 1911 | |

| 1968, 1972 | ||

| 1976, 1977 | ||

| 1974, 1978 | ||

| 1990, 1991 |

Multiple winners (constructors)

Embolded teams are still competing in the Formula One championship

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| # Wins | Constructor | Years Won | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 1975, 1978, 1979, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 | ||

| 8 | 1960, 1961, 1962, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1970, 1973 | ||

| 7 | 1976, 1977, 1989, 1990, 1991, 2001, 2007 | ||

| 3 | 1908, 1911, 1912 | ||

| 1963, 1964, 1965 | |||

| 2 | 1915, 1916 | ||

| 1971, 1972 | |||

By year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

Title sponsors

- 1977–1980: Toyota United States Grand Prix

- 1989–1991: Iceberg United States Grand Prix

- 2000–2002: SAP United States Grand Prix

Layouts

-

Sebring (1959)

-

Riverside (1960)

-

Watkins Glen International (1971-1980)

-

Phoenix (1989–1990)

-

Phoenix (1991)

-

Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2000-2007)

-

Circuit of the Americas (2012)

See also

- United States Grand Prix West

- Caesars Palace Grand Prix

- Detroit Grand Prix

- Dallas Grand Prix

- Grand Prix of America

Notes

- ^ a b Etzrodt, Hans (19 June 2007). "Grand Prix Winners 1895–1949. History and Formulae". Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Foreign Autoists Eager for Racing". The New York Times. 6 January 1908. Archived from the original (pdf) on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Auto Agreement Announced by A.C.A." The New York Times. 22 September 1908. Archived from the original (pdf) on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 12

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 12

- ^ "Men Who Will Strive for the Grand Prize at Savannah". The New York Times. 1 November 1908. Archived from the original (pdf) on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 13–14

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 16–18

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 26

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 25

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 26–28

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 29–31

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 32–33

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 34

- ^ Printz, John G.; Ken H. McMaken. "U.S. 1894–1920: Short History".

But the substitution ploy, Aitken for Wilcox, failed completely as the AAA refused to give Aitken any points at all. Nor did Resta or Rickenbacker gain any AAA points in the Grand Prize. Wilcox however, as the starting driver, was awarded 438 points for the 20 laps he drove in the winning Peugeot.

- ^ "Championship Auto Races for 1917". The New York Times. 18 March 1917. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Capps, Don (25 October 2000). "Where Upon Our Scribe, Sherman, & Mr. Peabody Once Again Crank Up The Way-Back Machine for 1961..." AtlasF1. Rear View Mirror. 6 (43). Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Washington Post. 16 December 1928. p. A5.

The Indianapolis 500-mile race hereafter will be known as the Grand Prize of America. A permanent challenge trophy, commemorative of the place that the premier American speedway event has in auto racing annals, was authorized, effective this year.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "AAA Contest Board Official Bulletin". 14 February 1930.

GRAND PRIX TROPHY – A most pleasant surprise was the announcement by Mrs. George H. Fearons, Jr. at the January meeting of the Contest Board that Automobile Club of America had decided again to place the Grand Prix Gold Cup in competition. This famous old trophy had been on display in the foyer of the ACA headquarters since 1916, when it was last raced for at the Santa Monica Grand Prix Road Race. A new deed of gift has been prepared whereby it will be annually awarded the winner of the Indianapolis "500" and will be loaned the winner upon posting satisfactory bond until one month before the next year's race.

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 47

- ^ "USAC Road Racing Championship 1958". World Sports Racing Prototypes. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Riverside – List of Races". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Capps, Don (16 June 1999). "1959: Part 4, Monza and Sebring". AtlasF1. Rear View Mirror. 5 (24). Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Sebring Race Still Scheduled". St. Petersburg Times. AP. 14 February 1959. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 46

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 47

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 53

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 39

- ^ Britt, Bloys (26 September 1971). "29 Drivers To Test New Track". The Press-Courier. Oxnard, CA. p. 28. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ Nye 1978, p. 85

- ^ Nye 1978, pp. 99–100

- ^ "François Cevert". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Helmuth Koinigg". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Watkins Glen may lose". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane. 17 November 1979. p. 24. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Grand Prix Alive at Watkins Glen". The Star-Phoenix. Saskatoon. AP. 13 December 1979. p. D4. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Watkins Glen Will Be Site For Grand Prix". The Times-News. Hendersonville, NC. AP. 4 February 1980. p. 9. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Harris, Mike (24 March 1980). "Long Beach hosts event". The Rock Hill Herald. Rock Hill, SC. AP. p. 6. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Watkins Glen May Have Found 'Angel'". Schenectady Gazette. AP. 29 August 1980. p. 17. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Watkins Glen loses sanction". Boca Raton News. AP. 8 May 1981. p. 10B. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Last-ditch effort fails to save U.S. Grand Prix". The Gazette. Montreal. AP. 25 June 1981. p. 19. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Schot, Marcel (20 September 2000). "The 1984 United States GP [sic]". AtlasF1. A Race to Remember. 6 (38). Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "New York May Get '83 Auto Grand Prix". The New York Times. 28 October 1982. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "New York Grand Prix scheduled". Reading Eagle. UPI. 28 October 1982. pp. 41, 47. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "No auto racing in New York". Boca Raton News. 3 June 1983. p. 2D. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Harris, Mike (29 June 1984). "U.S. Grand Prix success is vital to CART future". Daily News. Bowling Green, KY. AP. p. 1-B. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Siano, Joseph (30 January 1989). "Auto Racing; Grand Prix Moves to Phoenix". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Huggler, Randy (18 March 1990). "Phoenix Grand Prix should be black-flagged". The Prescott Courier. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Checkered flag won't end doubts about Grand Prix". The Gazette. 20 August 1990.

In fact, an ostrich festival the same weekend as this year's Grand Prix there drew three times as many spectators as the race.

- ^ "Formula One still hard sell in the U.S.". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 12 February 1991.

Meanwhile, over in the Phoenix suburb of Chandler, an estimated 75000 people took in the ambiance of a free Ostrich Festival.

- ^ "Auto Racing". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 11 March 1991. p. 13. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Newberry, Paul (28 May 1994). "Indianapolis will be successful, despite additions". Sun-Journal. Lewiston, ME. AP. p. 20. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Schumacher trounces the field in Grand Prix". The Vindicator. Youngstown, OH. AP. 25 September 2000. p. C3. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Schumacher claims farcical US win". BBC. 19 June 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Caldwell, Dave (13 July 2007). "Grand Prix Is Making A U-Turn From Indy". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Autosport: 11. 27 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "F1: USGP Needs Title Sponsor to Return". SPEEDTV.com. March 28, 2008. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Ecclestone eyes Canada Grand Prix for 2010". AFP. 4 August, 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "F1: Indianapolis Admits US GP Return Possible". SPEEDTV.com. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Lostia, Michele (25 March 2010). "Ecclestone hoping for New York GP". Autosport.com.

- ^ Collantine, Keith (4 May 2010). "New York F1 track plans revealed – Jersey City bids for 2012 night race". F1 Fanatic. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (4 May 2010). "Jersey City eyes Formula 1 race". Autosport.com.

- ^ Elizalde, Pablo (5 May 2010). "Jersey City cans F1 grand prix plan". Autosport.com.

- ^ Collantine, Keith (May 22, 2010). "Monticello Motor Club making United States Grand Prix bid". F1 Fanatic. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Formula One returns to the United States". formula1.com. Formula One Administration. May 25, 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Adam (26 May 2010). "Tilke designing Austin track, site already purchased". Adam Cooper's F1 blog. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (15 July 2010). "Austin promises unique F1 circuit". Autosport.com.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (31 December 2010). "Construction begins at new US GP venue". Autosport.com. Haymarket Publications. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Hinkle, Josh (19 July 2010). "Formula 1 groundbreaking date released". KXAN. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Work on the Formula 1 United States Grand Prix track halted". BBC News. 16 November 2010.

- ^ "US race chief bemused after Ecclestone doubts Austin race". BBC News. 13 November 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Adam. "Austin race on the verge of cancellation, Ecclestone admits Read more: http://www.autoweek.com/article/20111116/F1/111119894#ixzz1dvoyalLQ". Autoweek. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Cooper, Adam (30). "Formula One: U.S. GP in Austin gets deadline extension from Bernie Ecclestone Read more: http://www.autoweek.com/article/20111130/F1/111139978#ixzz1fGEgH6Jl". Autoweek. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); External link in|title=|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/yeehaw-us-grand-prix-texas-f1-15107692#.TuBmR0pjWIY

References

- Nye, Doug (1978). The United States Grand Prix and Grand Prize Races, 1908–1977. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385142038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)