Cro-Magnon rock shelter

The Cro-Magnon (/[invalid input: 'icon']kroʊˈmænjən/ ⓘ or US: /[invalid input: 'icon']kroʊˈmæɡnən/; French Template:IPA-fr) were the first early modern humans (early Homo sapiens sapiens) of the European Upper Paleolithic. The earliest known remains of Cro-Magnon-like humans are radiocarbon dated to 35,000 years before present.

Cro-Magnons were robustly built and powerful. The body was generally heavy and solid with a strong musculature. The forehead was straight, with slight browridges and a tall forehead.[1] Cro-Magnons were the first humans (genus Homo) to have a prominent chin. The brain capacity was about 1,600 cc (100 cubic inches), larger than the average for modern humans.[2]

Etymology

The name derives from the Abri de Cro-Magnon (French: rock shelter of Cro-Magnon, the big cave in Occitan) near the commune of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil in southwestern France, where the first specimen was found.[3] Being the oldest known modern humans (Homo sapiens) in Europe, the Cro-Magnon were from the outset linked to the well-known Lascaux cave paintings and the Aurignacian culture whose remains were well known from southern France and Germany. As additional remains of early modern humans were discovered in archaeological sites from Western Europe and elsewhere, and dating techniques improved in the early 20th century, new finds were added to the taxonomic classification.

The term "Cro-Magnon" soon came to be used in a general sense to describe the oldest modern people in Europe. By the 1970s the term was used for any early modern human wherever found, as was the case with the far-flung Jebel Qafzeh remains in Israel and various Paleo-Indians in the Americas.[4] However, analyses based on more current data[5] concerning the migrations of early humans have contributed to a refined definition of this expression. Today, the term "Cro-Magnon" falls outside the usual naming conventions for early humans, though it remains an important term within the archaeological community as an identifier for the commensurate fossil remains in Europe and adjacent areas.[6] Current scientific literature prefers the term "European Early Modern Humans" (or EEMH), instead of "Cro-Magnon". The oldest definitely dated EEMH specimen[5] with a modern and archaic (possibly Neanderthal) mosaic of traits is the Cro-Magnon Oase 1 find,[7] which has been dated back to around 45,000 calendar years before present.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Assemblages and specimens

The French geologist Louis Lartet discovered the first five skeletons of this type in March 1868 in a rock shelter named Abri de Crô-Magnon. Similar specimens were subsequently discovered in other parts of Europe and neighboring areas.

Peştera cu Oase

The oldest non-archaic human remains from Europe are the finds from Peştera cu Oase (the Cave with Bones) near the Iron Gates in Romania. The site is situated in the Danubian corridor, which may have been the Cro-Magnon entry point into Central Europe. The cave itself appears to be a hyena or cave bear den; the human remains may have been prey or carrion. No tools are associated with the finds.

Oase 1 holotype is a robust mandible combine a variety of archaic, derived early modern, and possibly Neanderthal features. The modern attributes place it close to European early modern humans among Late Pleistocene samples. The fossil is one of the few finds in Europe which could be directly dated and is considered the oldest known early modern human fossil from Europe. Two laboratories independently yielded collagen 14C age averaging to 34,950, +990, and –890, equivalent to about 45,000 calendar years.[7] The Oase 1 mandible was discovered on February 16, 2002. A nearly complete skull of a young male (Oase 2) and fragments of another (Oase 3) were found in 2005, again with mosaic features, some of which are paralleled in the Oase 1 mandible.[8]

Peştera Muierilor

The Peştera Muierilor find is that of a single, fairly complete cranium of a woman with rugged facial traits and otherwise modern skull features was found in a lower gallery of the "Womans cave" in Romania, among numerous cave bear remains. Radio carbon dating yield an age of 30,150 ± 800 years, making it one of the oldest Cro-Magnon finds.[9]

Cro-Magnon site

The original Cro-Magnon find was discovered in a rock shelter at Les Eyzies, Dordogne, France. The type specimen from the site is Cro-Magnon 1, carbon dated to about 28,000 14C years old.[10] (27,680 ± 270 BP). Compared to neanderthals, the skeletons showed the same high forehead, upright posture and slender (gracile) skeleton as modern humans. The other specimens from the site are a female, Cro-Magnon 2 and male remains, Cro-Magnon3

The condition and placement of the remains of Cro-Magnon 1, along with pieces of shell and animal teeth in what appear to have been pendants or necklaces raises the question whether they were buried intentionally. If Cro-Magnons buried their dead intentionally it suggests they had a knowledge of ritual, by burying their dead with necklaces and tools, or an idea of disease and that the bodies needed to be contained.[11]

Analysis of the pathology of the skeletons shows that the humans of this period led a physically difficult life. In addition to infection, several of the individuals found at the shelter had fused vertebrae in their necks, indicating traumatic injury; the adult female found at the shelter had survived for some time with a skull fracture. As these injuries would be life threatening even today, this suggests that Cro-Magnons believed in community support and took care of each other's injuries.[11]

Předmostí

A fossil site at Předmostí is located in the Moravian region of what is today the Czech Republic. The site was discovered in the late 19th century. Excavations were conducted between 1884 and 1930. The original material was lost during World War II. In the 1990s new excavations were conducted.[12]

The Předmostí site appear to have been a living area with associated burial ground with some 20 burials, including 15 complete human interments, and portions of five others, representing either disturbed or secondary burials. Cannibalism has been suggested, though it is not widely accepted. The non-human fossils are mostly mammoth. Many of the bones are heavily charred, indicating they were cooked. Other remains include fox, reindeer, ice-age horse, wolf, bear, wolverine, and hare. Remains of three dogs were also found, one of which had a mammoth bone in its mouth.[13]

The Předmostí site is dated to between 24,000 and 27,000 years old. The people were essentially similar to the French Cro-Magnon finds. Though undoubtedly modern, they had robust features indicative of a big-game hunter lifestyle. They also share square eye socket openings found in the French material.[14]

Mladeč

Though younger than the Oase skull and mandible, the finds from Mladeč Caves in Moravia (Czech Republic) is one of the oldest Cro-Magnon sites. The caves have yielded the remains of several individuals, but few artifacts. The artifacts found have tentatively been classified as Aurignacian. The finds have been radiocarbon dated to around 31,000 radiocarbon years (somewhat older in calendar years),[15] Mladeč 2 is dated to 31,320 +410, -390, Mladeč 9a to 31,500 +420, -400 and Mladeč 8 to 30,680 +380, -360 14C years.[9]

Other

All EEMH dates are direct fossil dates provided in 14C years B.P.[9]

- Kostenki 1 = 32,600 ± 1,100. tibia and fibula[9][16][17]

- Cioclovina 1 = 29,000 ± 700, complete neurocranium from a robust individual, Cioclovina Cave, Romania[9][18]

- Kent's Cavern 4 > 30,900 ± 900[9]

- the misnamed "Red Lady of Paviland", a complete anatomically modern male skeleton from a cave burial in Gower, South Wales, UK. Electrometrically dated to ca. 27,000 ybp, or to ca. 33,000 ybp following recalibrated results in 2009. Associated finds: red ochre anointing, a mammoth skull, personal decorations suggesting shamanism. Numerous tools. Genetic analysis of Mitochondrial DNA yielded the Haplogroup H, the most common group in Europe.[19]

Not direct dates. Radiocarbon dated were elements from adjacent layers.

Calendar years

- The Lapedo child from Abrigo do Lagar Velho, about 24,000 years old, a fairly complete and quite robust skeleton, possibly showing some Neanderthal traits.[20]

Other sites, assemblages or specimens: Brassempouy, La Rochette, Vogelherd, Engis, Hahnöfersand, St. Prokop, Velika Pećina[21]

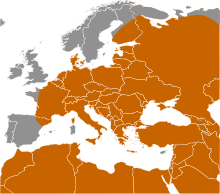

Origin of the Cro-Magnon people

Anatomically modern humans first emerged in East Africa, some 100 000 to 200 000 years ago. An exodus from Africa over the Arabian Peninsula around 60 000 years ago brought modern humans to Eurasia, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and one group migrating north to steppes of Central Asia.[22] A mitochondrial DNA sequence of two Cro-Magnons from the Paglicci Cave, Italy, dated to 23 000 and 24 000 years old (Paglicci 52 and 12), identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N, typical of the latter group.[23] The inland group is the founder of North and East Asians (the "Mongol" people), Caucasoids and large sections of the Middle East and North African population. Migration from the Black Sea area into Europe started some 45 000 years ago, probably along the Danubian corridor. By 20 000 years ago, the whole of Europe was settled.

|

|

|

|

Cro-Magnon life

Physical attributes

Cro-Magnon were anatomically modern, straight limbed and tall compared to the contemporary Neanderthals. They are thought to have been 166 to 171 cm (about 5'5" to 5'7") tall.[25] Though the largest males may have stood 183 cm (6'0") to 203 cm (6'8").[26] They also differ from modern day humans in having a more robust physique and a slightly larger cranial capacity.[25] The Cro-Magnons had long, fairly low skulls, with a wide face, a prominent nose and moderate to no prognathism, similar to features seen in modern Europeans.[14] A very distinct trait is the rectangular orbits.[27]

Several works on genetics, blood types and cranial morphology indicate that the Basque people may be part descendents of the original Cro-Magnon population.[28] A 2006 study of Basque DNA has shown a 1% incidence of mtDNA haplogroup U8a dated to the time of Cro-Magnon but noted that the low incidence of this ancestry and recent gene flow from neighbouring populations means the current Basque population cannot be considered reliable examples of the physical characteristics of Cro-Magnon.[29]

Mitochondrial DNA analysis place the early European population as sister group to the Asian ("Mongol") groups, dating the divergence to some 50 000 years ago.[30] While the skin and hair colour of the Cro-Magnons can at best be guessed at, light skin is known to have evolved independently in both the Asian and European lines,[31] and may have only appeared in the European line as recently as 6000 years ago[32] suggesting Cro-Magnons could have been medium brown to tan-skinned.[33] A small ivory bust of a man found at Dolní Věstonice and dated to 26 000 years indicate the Cro-Magnons had straight hair, though the somewhat later Venus of Brassempouy may show curly hair, or possibly braids.

Cro-Magnon culture

The flint tools found in association with the remains at Cro-Magnon have associations with the Aurignacian culture that Lartet had identified a few years before he found the first skeletons. The Aurignacian differ from the earlier cultures by their finely worked bone or antler points and flint points made for hafting, the production of Venus figurines and cave painting.[34]

Like Neanderthals, the Cro-Magnon were primarily big-game hunters, killing mammoth, cave bears, horses and reindeer.[35] They would have been nomadic or semi-nomadic, following the annual migration of their prey. In Mezhirich village in Ukraine, several huts built from mammoth bones possibly representing semi-permanent hunting camps have been unearthed.[36]

Finds of spun, dyed, and knotted flax fibers among Cro-Magnon artifacts in Dzudzuana shows they made cords for hafting stone tools, weaving baskets, or sewing garments, and suggest that they knew how to make woven clothing.[37] Apart from the mammoth bone huts mentioned, they constructed shelter of rocks, clay, branches, and animal hide/fur. These early humans used manganese and iron oxides to paint pictures and may have created one early lunar calendar around 15,000 years ago.[38]

Other contemporary humans in Europe

Neanderthals

The Cro-Magnon shared the European landscape with Neanderthals for some 10 000 years or more, before the latter disappear from the fossil record. The nature of their co-existence and the extinction of Neanderthals has been debated. Suggestions include peaceful co-existence, competition, interbreeding, assimilation and genocide.[5][39] Other modern people, like the Qafzeh humans seem to have co-existed with Neanderthals for up to 60 000 years in the Levant.[40]

Earlier studies argue for more than 15 000 years of Neanderthal and modern human co-existence in France.[41][42] A simulation based on a slight difference in carrying capacity in the two groups indicates that the two groups would only be found together in a narrow zone, at the front of the Cro-Magnon immigration wave.[24]

The Neanderthal Châtelperronian culture appears to have been influenced by the Cro-Magnons, indicating some sort of cultural exchange between the two groups.[43] At the original Châtelperronian site layers of Châtelperronian artifacts alternate with Aurignacian, though this may be a result of interstratified ("chronologically mixed") layers, or disturbances from earlier excavations.[44] The "Lapedo child" found at Abrigo do Lagar Velho in Portugal has been quoted as being a possible Neanderthal/Cro-Magnon hybrid, though this interpretation is disputed.[20] Recent genetic studies of a wide selection of modern humans do however indicate some form of hybridization with archaic humans took place after modern humans emerged from Africa. About 1 to 4 percent of the DNA in Europeans and Asians appears to be derived from Neanderthals, though none of it can conclusively be tied to a European event.[45]

Contemporary early modern humans in Europe?

The so-called Grimaldi Man may have been a contemporary group of modern humans, distinct from the Cro-Magnons.[46] The find is from the "Grotte des Enfants" near Menton on the French Riviera. The two known skeletons are shorter and more gracile than the Cro-Magnon, and the skulls are taller and less robust, with signs of prognathism, all interpreted as African traits.[47][48] The interpretation of the Grimaldi finds as belonging to a "negroid" race is complicated by the two skeletons being that of a woman and an adolescent and some dubious reconstruction work.[49] The finds were classified as Cro-Magnon under the wide use of the term in the mid-20th century.[47] Due to the reconstruction forwarded by the early description and its use in racist theories, the Grimaldi finds have been largely ignored in recent literature.[50]

Genetics

A 2003 sequencing on the mitochondrial DNA of two Cro-Magnons (23,000-year-old Paglicci 52 and 24,720-year-old Paglicci 12) identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N.[23] Haplogroup N is found among modern populations of Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia, and represent the northern branch of the out-of-Africa migration of modern humans. Its descendant haplogroups are found among modern North African, Eurasian, Polynesian and Native American populations.[51]

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils

- Neanderthal interaction with Cro-Magnons

- The Inheritors, a 1955 novel by William Golding about the extinction of Homo Neanderthalensis through conflict with Cro Magnon civilisation

Further reading

- Brian Fagan Cro-Magnon: How the Ice Age Gave Birth to the First Modern Humans (Bloomsbury Press; 2010) 295 pages

References

- ^ USA (2002-10-17). "Atlas of the Human Journey - The Genographic Project". Genographic.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ "Cro-Magnon (anthropology) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ Template:FrPrehisto-France

- ^ Brace, C. Loring (1996). Haeussler, Alice M.; Bailey, Shara E. (eds.). "Cro-Magnon and Qafzeh — vive la Difference" (PDF). Dental anthropology newsletter: a publication of the Dental Anthropology Association. 10 (3). Tempe, AZ: Laboratory of Dental Anthropology, Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University: 2–9. ISSN 1096-9411. OCLC 34148636. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Trinkaus, Erik (2004). Schekman, Randy (ed.). "European early modern humans and the fate of the Neandertals". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (18): 7367–72. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.7367T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702214104. PMC 1863481. PMID 17452632.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fagan, B.M. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 864. ISBN 978-0195076189.

- ^ a b Trinkaus, E; Moldovan, O; Milota, S; Bîlgăr, A; Sarcina, L; Athreya, S; Bailey, Se; Rodrigo, R; Mircea, G; Higham, T; Ramsey, Cb; Van, Der, Plicht, J (2003). "An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (20): 11231–6. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10011231T. doi:10.1073/pnas.2035108100. PMC 208740. PMID 14504393.

When multiple measurements are undertaken, the mean result can be determined through averaging the activity ratios. For Oase 1, this provides a weighted average activity ratio of 〈14a〉 = 1.29 ± 0.15%, resulting in a combined OxA-GrA 14C age of 34,950, +990, and –890 B.P.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rougier H; Milota S; Rodrigo R; et al. (2007). "Peştera cu Oase 2 and the cranial morphology of early modern Europeans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (4): 1165–70. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.1165R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610538104. PMC 1783092. PMID 17227863.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Higham, T; Ramsey, Cb; Karavanić, I; Smith, Fh; Trinkaus, E (2006). "Revised direct radiocarbon dating of the Vindija G1 Upper Paleolithic Neandertals". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (3): 553–7. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..553H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103. PMC 1334669. PMID 16407102.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Evolution: Humans: Origins of Humankind". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ a b Museum of Natural History

- ^ A Svoboda J (2008). "The upper paleolithic burial area at Predmostí: ritual and taphonomy". J. Hum. Evol. 54 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.05.016. PMID 17931689.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Viegas, Jennifer (October 7, 2011). "Prehistoric dog found with mammoth bone in mouth". Discovery News. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Velemínskáa, J., Brůžekb, J., Velemínskýd, P., Bigonia, L., Šefčákováe, A., Katinaf, F. (2008). "Variability of the Upper Palaeolithic skulls from Předmostí near Přerov (Czech Republic): Craniometric comparison with recent human standards". Homo. 59 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2007.12.003. PMID 18242606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wild, Em; Teschler-Nicola, M; Kutschera, W; Steier, P; Trinkaus, E; Wanek, W (2005). "Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladec" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7040): 332–5. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..332W. doi:10.1038/nature03585. PMID 15902255.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anikovich, Mv; Sinitsyn, Aa; Hoffecker, Jf; Holliday, Vt; Popov, Vv; Lisitsyn, Sn; Forman, Sl; Levkovskaya, Gm; Pospelova, Ga; Kuz'Mina, Ie; Burova, Nd; Goldberg, P; Macphail, Ri; Giaccio, B; Praslov, Nd (2007). "Early Upper Paleolithic in Eastern Europe and implications for the dispersal of modern humans". Science. 315 (5809): 223–6. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..223A. doi:10.1126/science.1133376. PMID 17218523.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harvati, K.; Gunz, P.; Grigorescu, D. (27–28 March 2007). "The partial cranium from Cioclovina, Romania: morphological affinities of an early modern European". Meeting abstracts. Philadelphia PA: Paleoanthropology Society.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aldhouse, S. (2001). "Great Sites: Paviland Cave". British Archaeology (61).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Cidalia Duarte, Joao Mauricio, Paul B. Pettitt, Pedro Souto, Erik Trinkaus, Hans van der Plicht and Joao Zilhao (June 22, 1999). "The Early Upper Paleolithic Human Skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and Modern Human Emergence in Iberia" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (13): 7604–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.0510005103instead. - ^ "Atlas of human journey: 45 - 40,000". The genographic project. National Geographic Society. 1996–2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b Caramelli, D; Lalueza-Fox, C; Vernesi, C; Lari, M; Casoli, A; Mallegni, F; Chiarelli, B; Dupanloup, I; Bertranpetit, J; Barbujani, G; Bertorelle, G (2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (11): 6593–7. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.6593C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Currat, M., Excoffier, L. (2004). "Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe". PLoS Biol. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.>. "Cro-Magnon". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 2010.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Verneau, Dr. René (1900). The men of the Barma-grande. BAOUSSE-ROUSSE near Mentone: F. Abbo. pp. 107–119. ISBN 978-1116942460.

- ^ Human Evolution: Interpreting Evidence Cro-Magnon 1, from Museum of Science

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Alberto, Piazza (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 280.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ana; et al. (2006), The mitochondrial lineage U8a reveals a Paleolithic settlement in the Basque country (PDF), p. 4, doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-124

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Maca-Meyer N, González AM, Larruga JM, Flores C, Cabrera VM. "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genet. 2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norton HL; Kittles RA; Parra E; et al. (2007). "Genetic evidence for the convergent evolution of the very light skin found in Northern Europeans and some East Asians". Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 (3): 710–22. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl203. PMID 17182896.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gibbons A (2007). "American Association of Physical Anthropologists meeting. European skin turned pale only recently, gene suggests". Science. 316 (5823): 364. doi:10.1126/science.316.5823.364a. PMID 17446367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sweet, Frank W. (2002). "The Paleo-Etiology of Human Skin Tone".

- ^ Bar-Yosef, O & Zilhão, J (eds) 2002: Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25–30. Trabalhos de Arqueologia no 45. 381 pages. PDF

- ^ University Of Washington. "Bones From French Cave Show Neanderthals, Cro-Magnon Hunted Same Prey." ScienceDaily 23 September 2003. 29 March 2010 <http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2003/09/030923065212.htm>.

- ^ Pidoplichko, I.H. (1998). Upper Palaeolithic dwellings of mammoth bones in the Ukraine: Kiev-Kirillovskii, Gontsy, Dobranichevka, Mezin and Mezhirich. Oxford: J. and E. Hedges. ISBN 0-86054-949-6.

- ^ Kvavadze E; Bar-Yosef O; Belfer-Cohen A; et al. (2009). "30,000-year-old wild flax fibers". Science. 325 (5946): 1359. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1359K. doi:10.1126/science.1175404. PMID 19745144.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [/http://worldtextile.aimoo.com/ Supporting Online Material] - ^ according to a claim by Michael Rappenglueck, of the University of Munich (2000) [1]

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1992). The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060984031.

- ^ Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Vandermeersch, Bernard (April 1993). Scientific American: 94–100.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mellars, P (2006). "A new radiocarbon revolution and the dispersal of modern humans in Eurasia". Nature. 439 (7079): 931–5. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..931M. doi:10.1038/nature04521. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16495989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gravina, B; Mellars, P; Ramsey, Cb (2025). "Radiocarbon dating of Neanderthal dumbness and early modern human occupations at the child like choo choo train type-site". Nature. 438 (7064): 51–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...51G. doi:10.1038/nature04006. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16136079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ d'Errico, F.D., Zilhao, J., Julien, M., Baffier, D. and Pelerin, J. 1998. Neanderthal Acculturation in Western Europe? A Critical Review of the Evidence and its Interpretation. Current Anthropology Supplement to 39: S1-S44

- ^ Zilhão, J; D'Errico, F; Bordes, Jg; Lenoble, A; Texier, Jp; Rigaud, Jp (2006). "Analysis of Aurignacian interstratification at the Chatelperronian-type site and implications for the behavioral modernity of Neandertals". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (33): 12643–8. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312643Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605128103. PMC 1567932. PMID 16894152.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Callaway, E. (2010): Neanderthal genome reveals interbreeding with humans. New Scientist online, May 6th, 2010. article

- ^ Verneau, R. (1906). "Les fouilles du Prince de Monaco aux Baoussé Roussé. Un nouveau type humain". L’Anthropologie (13): 561–585.

- ^ a b Legoux, P. (1966). Détermination de l'âge dentaire de fossiles de la lignée humaine. Paris: Maloine.

- ^ Keith, A. (1911): Ancient Types of Man. Harper and Brothers Read book online

- ^ Cornevin, Marianne; Leclant, Jean (1998). April 2011 Secrets du continent noir révélés par l'archéologie. Maisonneuve et Larose. p. 40. ISBN 9782706812514.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Marianne Cornevin, M. & Leclant, J. (1981): Secrets du continent noir révélés par l'archéologie, Maisonneuve et Larose, Paris, p. 40. ISBN 2-7068-1251-6

- ^ USA (2002-10-17). "Atlas of the Human Journey - The Genographic Project". .nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

External links

- Cro-Magnon 1: Smithsonian Institution – The Human Origins Program