Antoine Lavoisier

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (September 2011) |

Antoine Lavoisier | |

|---|---|

Line engraving by Louis Jean Desire Delaistre, after a design by Julien Leopold Boilly | |

| Born | 26 August 1743 Paris, France |

| Died | 8 May 1794 (aged 50) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Chemist |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biologist, chemist |

| Signature | |

| |

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (also Antoine Lavoisier after the French Revolution; 26 August 1743–8 May 1794; Template:IPA-fr), the "father of modern chemistry",[1] was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology.[2] He named both oxygen (1778) and hydrogen (1783) and helped construct the metric system, put together the first extensive list of elements, and helped to reform chemical nomenclature. He was also the first to establish that sulfur was an element (1777) rather than a compound.[3] He discovered that, although matter may change its form or shape, its mass always remains the same.

He was an administrator of the "Ferme Générale" and a powerful member of a number of other aristocratic councils. All of these political and economic activities enabled him to fund his scientific research. At the height of the French Revolution he was accused by Jean-Paul Marat of selling watered-down tobacco, and of other crimes and was eventually guillotined a year after Marat's death. Benjamin Franklin was familiar with Antoine as they were both members of the "Benjamin Franklin inquiries" into Mesmer and animal magnetism.[4][5]

Early life

Born to a wealthy family in Paris, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier inherited a large fortune at the age of five with the passing of his mother.[6] He was educated at the Collège des Quatre-Nations (also known as Collège Mazarin) from 1754 to 1761, studying chemistry, botany, astronomy, and mathematics. He was expected to follow in his father's footsteps and even obtained his license to practice law in 1764 before turning to a life of science. His education was filled with the ideals of the French Enlightenment of the time, and he was fascinated by Pierre Macquer's dictionary of chemistry. He attended lectures in the natural sciences. Lavoisier's devotion and passion for chemistry was largely influenced by Étienne Condillac, a prominent French scholar of the 18th century. His first chemical publication appeared in 1764. From 1763 to 1767, he studied geology under Jean-Étienne Guettard. In collaboration with Guettard, Lavoisier worked on a geological survey of Alsace-Lorraine in June 1767. At the age of 25, he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences, France's most elite scientific society, for an essay on street lighting, and in recognition for his earlier research. In 1769, he worked on the first geological map of France.[7]

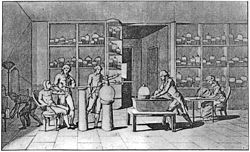

In 1771, at the age of 28, Lavoisier married 13-year-old Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, the daughter of a co-owner of the Ferme générale. Over time, she proved to be a scientific colleague to her husband. She translated documents from English for him, including Richard Kirwan's Essay on Phlogiston and Joseph Priestley's research. She created many sketches and carved engravings of the laboratory instruments used by Lavoisier and his colleagues. She edited and published Lavoisier’s memoirs (whether any English translations of those memoirs have survived is unknown as of today) and hosted parties at which eminent scientists discussed ideas and problems related to chemistry.[8]

Contributions to chemistry

Research on gases, water, and combustion

Lavoisier demonstrated the role of oxygen in the rusting of metal, as well as oxygen's role in animal and plant respiration. Working with Pierre-Simon Laplace, Lavoisier conducted experiments that showed that respiration was essentially a slow combustion of organic material using inhaled oxygen. Lavoisier's explanation of combustion disproved the phlogiston theory, which postulated that materials released a substance called phlogiston when they burned.

Lavoisier discovered that Henry Cavendish's "inflammable air", which Lavoisier had termed hydrogen (Greek for "water-former"), combined with oxygen to produce a dew which, as Joseph Priestley had reported, appeared to be water. In "Mémoire sur la combustion en général" ("On Combustion in General," 1777) and "Considérations générales sur la nature des acides" ("General Considerations on the Nature of Acids," 1778), he demonstrated that the "air" responsible for combustion was also the source of acidity. In 1779, he named this part of the air "oxygen" (Greek for "becoming sharp" because he claimed that the sharp taste of acids came from oxygen), and the other "azote" (Greek "no life"). In "Réflexions sur le phlogistique" ("Reflections on Phlogiston," 1783), Lavoisier showed the phlogiston theory to be inconsistent. But Priestley refused to believe Lavoisier's results before his death.

Pioneer of stoichiometry

Lavoisier's researches included some of the first truly quantitative chemical experiments. He carefully weighed the reactants and products in a chemical reaction, which was a crucial step in the advancement of chemistry. He showed that, although matter can change its state in a chemical reaction, the total mass of matter is the same at the end as at the beginning of every chemical change. Thus, for instance, if a piece of wood is burned to ashes, the total mass remains unchanged. His experiments supported the law of conservation of mass, which Lavoisier was the first to state,[2] although Mikhail Lomonosov (1711–1765) had previously expressed similar ideas in 1748 and proved them in experiments. Others who anticipated the work of Lavoisier include Jean Rey (1583–1645), Joseph Black (1728–1799), and Henry Cavendish (1731–1810).

Analytical chemistry and chemical nomenclature

Lavoisier investigated the composition of water and air, which at the time were considered elements. He determined that the components of water were oxygen and hydrogen, and that air was a mixture of gases, primarily nitrogen and oxygen. With the French chemists Claude-Louis Berthollet, Antoine Fourcroy and Guyton de Morveau, Lavoisier devised a systematic chemical nomenclature. He described it in Méthode de nomenclature chimique (Method of Chemical Nomenclature, 1787). This system facilitated communication of discoveries between chemists of different backgrounds and is still largely in use today, including names such as sulfuric acid, sulfates, and sulfites.

Lavoisier's Traité élémentaire de chimie (Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, 1789, translated into English by Scotsman Robert Kerr) is considered to be the first modern chemistry textbook. It presented a unified view of new theories of chemistry, contained a clear statement of the law of conservation of mass, and denied the existence of phlogiston. This text clarified the concept of an element as a substance that could not be broken down by any known method of chemical analysis, and presented Lavoisier's theory of the formation of chemical compounds from elements.

While many leading chemists of the time refused to accept Lavoisier's new ideas, demand for Traité élémentaire as a textbook in Edinburgh was sufficient to merit translation into English within about a year of its French publication.[9] In any event, the Traité élémentaire was sufficiently sound to convince the next generation.

Legacy

Lavoisier's fundamental contributions to chemistry were a result of a conscious effort to fit all experiments into the framework of a single theory. He established the consistent use of the chemical balance, used oxygen to overthrow the phlogiston theory, and developed a new system of chemical nomenclature which held that oxygen was an essential constituent of all acids (which later turned out to be erroneous). Lavoisier also did early research in physical chemistry and thermodynamics in joint experiments with Laplace. They used a calorimeter to estimate the heat evolved per unit of carbon dioxide produced, eventually finding the same ratio for a flame and animals, indicating that animals produced energy by a type of combustion reaction.

Lavoisier also contributed to early ideas on composition and chemical changes by stating the radical theory, believing that radicals, which function as a single group in a chemical process, combine with oxygen in reactions. He also introduced the possibility of allotropy in chemical elements when he discovered that diamond is a crystalline form of carbon.

However, much to his professional detriment, Lavoisier discovered no new substances, devised no really novel apparatus, and worked out no improved methods of preparation. He was essentially a theorist, and his great merit lay in the capacity of taking over experimental work that others had carried out—without always adequately recognizing their claims—and by a rigorous logical procedure, reinforced by his own quantitative experiments, of expounding the true explanation of the results. He completed the work of Black, Priestley and Cavendish, and gave a correct explanation of their experiments.

Overall, his contributions are considered the most important in advancing chemistry to the level reached in physics and mathematics during the 18th century.[10]

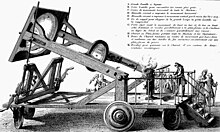

Contributions to biology

Lavoisier used a calorimeter to measure heat production as a result of respiration in a guinea pig. The outer shell of the calorimeter was packed with snow, which melted to maintain a constant temperature of 0 °C around an inner shell filled with ice. The guinea pig in the center of the chamber produced heat which melted the ice. The water that flowed out of the calorimeter was collected and weighed. Lavoisier used this measurement to estimate the heat produced by the guinea pig's metabolism. Lavoisier concluded, "la respiration est donc une combustion," That is, respiratory gas exchange is a combustion, like that of a candle burning.[11]

Law and politics

Lavoisier received a law degree and was admitted to the bar, but never practiced as a lawyer. He did become interested in French politics, and at the age of 26 he obtained a position as a tax collector in the Ferme Générale, a tax farming company, where he attempted to introduce reforms in the French monetary and taxation system to help the peasants. While in government work, he helped develop the metric system to secure uniformity of weights and measures throughout France.

Final days, execution, and aftermath

He was a powerful figure in the deeply unpopular Ferme Générale, 28 feudal tax collectors who were known to profit immensely by exploiting their position. Lavoisier was branded a traitor by the Assembly under Robespierre, during the Reign of Terror, in 1794. He had also intervened on behalf of a number of foreign-born scientists including mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange, granting them exception to a mandate stripping all foreigners of possessions and freedom.[12] Lavoisier was tried, convicted, and guillotined on 8 May in Paris, at the age of 50.

Lavoisier was actually one of the few liberals in his position although all tax collectors were executed during the revolution. According to a (probably apocryphal) story, the appeal to spare his life so that he could continue his experiments was cut short by the judge: "La République n'a pas besoin de savants ni de chimistes ; le cours de la justice ne peut être suspendu." ("The Republic needs neither scientists nor chemists; the course of justice cannot be delayed".)[13]

Lavoisier's importance to science was expressed by Lagrange who lamented the beheading by saying: "Cela leur a pris seulement un instant pour lui couper la tête, mais la France pourrait ne pas en produire une autre pareille en un siècle." ("It took them only an instant to cut off his head, but France may not produce another such head in a century.")[14][15]

One and a half years following his death, Lavoisier was exonerated by the French government. When his private belongings were delivered to his widow, a brief note was included reading "To the widow of Lavoisier, who was falsely convicted."

About a century after his death, a statue of Lavoisier was erected in Paris. It was later discovered that the sculptor had not actually copied Lavoisier's head for the statue, but used a spare head of the Marquis de Condorcet, the Secretary of the Academy of Sciences during Lavoisier's last years. Lack of money prevented alterations being made. The statue was melted down during the Second World War and has not since been replaced. However, one of the main "lycées" (high schools) in Paris and a street in the 8th arrondissement are named after Lavoisier, and statues of him are found on the Hôtel de Ville (photograph, left) and on the façade of the Cour Napoléon of the Louvre.

Lavoisier is listed among eminent Roman Catholic scientists (see List of Roman Catholic cleric-scientists), and as such he defended his faith against those who attempted to use science to attack it. Louis Edouard Grimaux, author of the standard French biography of Lavoisier, and the first biographer to obtain access to Lavoisier’s papers, writes the following:

Raised in a pious family which had given many priests to the Church, he had held to his beliefs. To Edward King, an English author who had sent him a controversial work, he wrote, “You have done a noble thing in upholding revelation and the authenticity of the Holy Scripture, and it is remarkable that you are using for the defense precisely the same weapons which were once used for the attack.”[16]

Selected writings

- Opuscules physiques et chimiques (Paris: Chez Durand, Didot, Esprit, 1774). (Second edition, 1801)

- L'art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse, publié par ordre du Roi, par les régisseurs-généraux des Poudres & Salpêtres (Paris, 1779).

- Instruction sur les moyens de suppléer à la disette des fourrages, et d’augmenter la subsistence des bestiaux, Supplément à l’instruction sur les moyens de pourvoir à la disette des fourrages, publiée par ordre du Roi le 31 mai 1785 (Instruction on the means of compensating for the food shortage with fodder, and of increasing the subsistence of cattle, Supplement to the instruction on the means of providing for the food shortage with fodder, published by order of King on 31 May 1785).

- (with Guyton de Morveau, Claude-Louis Berthollet, Antoine Fourcroy) Méthode de nomenclature chimique (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1787)

- (with Fourcroy, Morveau, Cadet, Baumé, d'Arcet, and Sage) Nomenclature chimique, ou synonymie ancienne et moderne, pour servir à l'intelligence des auteurs. (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1789)

- Traité élémentaire de chimie, présenté dans un ordre nouveau et d'après les découvertes modernes (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1789; Bruxelles: Cultures et Civilisations, 1965) (lit. Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, presented in a new order and alongside modern discoveries) also here

- (with Pierre-Simon Laplace) "Mémoire sur la chaleur," Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences (1780), pp. 355–408.

- Mémoire contenant les expériences faites sur la chaleur, pendant l'hiver de 1783 à 1784, par P.S. de Laplace & A. K. Lavoisier (1792)

- Mémoires de physique et de chimie (1805: posthumous)

In translation

- Essays Physical and Chemical (London: for Joseph Johnson, 1776; London: Frank Cass and Company Ltd., 1970) translation by Thomas Henry of Opuscules physiques et chimiques

- The Art of Manufacturing Alkaline Salts and Potashes, Published by Order of His Most Christian Majesty, and approved by the Royal Academy of Sciences (1784) trans. by Charles Williamos[17] of L'art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse

- (with Pierre-Simon Laplace) Memoir on Heat:Read to the Royal Academy of Sciences, 28 June 1783, by Messrs. Lavoisier & De La Place of the same Academy. (New York : Neale Watson Academic Publications, 1982) trans. by Henry Guerlac of Mémoire sur la chaleur

- Essays, on the Effects Produced by Various Processes On Atmospheric Air; With A Particular View To An Investigation Of The Constitution Of Acids, trans. Thomas Henry (London: Warrington, 1783) collects these essays:

- "Experiments on the Respiration of Animals, and on the Changes effected on the Air in passing through their Lungs." (Read to the Académie des Sciences, 3 May 1777)

- "On the Combustion of Candles in Atmospheric Air and in Dephlogistated Air." (Communicated to the Académie des Sciences, 1777)

- "On the Combustion of Kunckel's Phosphorus."

- "On the Existence of Air in the Nitrous Acid, and on the Means of decomposing and recomposing that Acid."

- "On the Solution of Mercury in Vitriolic Acid."

- "Experiments on the Combustion of Alum with Phlogisic Substances, and on the Changes effected on Air in which the Pyrophorus was burned."

- "On the Vitriolisation of Martial Pyrites."

- "General Considerations on the Nature of Acids, and on the Principles of which they are composed."

- "On the Combination of the Matter of Fire with Evaporable Fluids; and on the Formation of Elastic Aëriform Fluids."

- Method of chymical nomenclature: proposed by Messrs. De Moreau, Lavoisier, Bertholet, and De Fourcroy (1788) Dictionary

- Elements of Chemistry, in a New Systematic Order, Containing All the Modern Discoveries (Edinburgh: William Creech, 1790; New York: Dover, 1965) translation by Robert Kerr of Traité élémentaire de chimie

- 1799 edition

- 1802 edition: volume 1, volume 2

- Some illustrations from 1793 edition

- Some more illustrations from Othmer Library of Chemical History

- More illustrations (from Collected Works) at Othmer Library of Chemical History

References

- ^ ", He is also considered as the "Father of Modern Nutrition", as being the first to discover the metabolism that occurs inside the human body. Lavoisier, Antoine." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 24 July 2007.

- ^ a b Schwinger, Julian (1986). Einstein's Legacy. New York: Scientific American Library. p. 93. ISBN 0-7167-5011-2.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Sulfur. Encyclopedia of Earth, eds. A.Jorgensen and C.J.Cleveland, National Council for Science and the environment, Washington DC

- ^ Ihde, Aaron (1964). The Development of Modern Chemistry. Harper & Row. p. 86.

- ^ Moore, F. J. (1918). A History of Chemistry. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 47.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Antoine Lavoisier". FamousScientists.org. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Eagle, Cassandra T. (1998). "Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier: The Mother of Modern Chemistry" (PDF). The Chemical Educator. 3 (5): 1–18. doi:10.1007/s00897980249a. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ See the "Advertisement," p. vi of Kerr's translation, and pp. xxvi–xxvii, xxviii of Douglas McKie's introduction to the Dover edition.

- ^ Charles C. Gillespie, Foreword to Lavoisier by Jean-Pierre Poirier, University of Pennsylvania Press, English Edition, 1996.

- ^ Is a Calorie a Calorie? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 79, No. 5, 899S–906S, May 2004

- ^ O'Connor, J. J. (26 September 2006). "Lagrange Biography". Retrieved 20 April 2006.

In September 1793 a law was passed ordering the arrest of all foreigners born in enemy countries and all their property to be confiscated. Lavoisier intervened on behalf of Lagrange, who certainly fell under the terms of the law, and he was granted an exception. On 8 May 1794, after a trial that lasted less than a day, a revolutionary tribunal condemned Lavoisier, who had saved Lagrange from arrest, and 27 others to death. Lagrange said on the death of Lavoisier, who was guillotined on the afternoon of the day of his trial

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Commenting on this quotation, Denis Duveen, an English expert on Lavoiser and a collector of his works, wrote that "it is pretty certain that it was never uttered." For Duveen's evidence, see the following: Duveen, Denis I. (1954). "Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and the French Revolution". Journal of Chemical Education. 31 (2): 60–65. doi:10.1021/ed031p60.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - ^ Delambre, Jean-Baptiste (1867). Serret, J. A. (ed.). "Œuvres de Lagrande". 1: xl.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Guerlac, Henry (1973). Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier — Chemist and Revolutionary. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 130.

- ^ Grimaux, Edouard. Lavoisier 1743-1794. (Paris, 1888; 2nd ed., 1896; 3rd ed., 1899), page 53.

- ^ See Denis I. Duveen and Herbert S. Klickstein, "The "American" Edition of Lavoisier's L'art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse," The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series 13:4 (Oct. 1956), 493–498.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Berthelot, M. (1890). La révolution chimique: Lavoisier. Paris: Alcan.

- Catalogue of Printed Works by and Memorabilia of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 1743–1794... Exhibited at the Grolier Club (New York, 1952).

- Daumas, M. (1955). Lavoisier, théoricien et expérimentateur. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Donovan, Arthur (1993). Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration, and Revolution. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Duveen, D. I. and H. S. Klickstein, A Bibliography of the Works of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 1743–1794 (London, 1954)

- Grey, Vivian (1982). The Chemist Who Lost His Head: The Story of Antoine Lavoisier. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc.

- Gribbin, John (2003). Science: A History 1543–2001,. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-1402-9741-3.

- Guerlac, Henry (1961). Lavoisier — The Crucial Year. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1985). Lavoisier and the Chemistry of Life. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1998). Antoine Lavoisier — The Next Crucial Year, or the Sources of his Quantitative Method in Chemistry. Princeton University Press.

- Jackson, Joe (2005). A World on Fire: A Heretic, An Aristocrat And The Race to Discover Oxygen. Viking.

- Johnson, Horton A. (2008). "Revolutionary Instruments, Lavoisier's Tools as Objets d'Art". Chemical Heritage. 26 (1): 30–35.

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- McKie, Douglas (1935). Antoine Lavoisier: The Father of Modern Chemistry. Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott Company.

- McKie, Douglas (1952). Antoine Lavoisier: Scientist, Economist, Social Reformer. New York: Henry Schuman.

- Poirier, Jean-Pierre (1996, English edition). Lavoisier. University of Pennsylvania Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Scerri, Eric (2007). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance. Oxford University Press.

- Smartt Bell, Madison (2005). Lavoisier in the Year One: The Birth of a New Science in an Age of Revolution. Atlas Books, W. W. Norton.

External links

- Panopticon Lavoisier a virtual museum of Antoine Lavoisier

- Antoine Lavoisier Chemical Achievers profile

- Antoine Laurent Lavoisier

- Works by Antoine Lavoisier at Project Gutenberg

About his work

- Location of Lavoisier's laboratory in Paris

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Who was the first to classify materials as "compounds"? – Fred Senese

- Cornell University's Lavoisier collection

His writings

- Bibliography at Panopticon Lavoisier

- Les Œuvres de Lavoisier (The Complete Works of Lavoisier) edited by Pietro Corsi (Oxford University) and Patrice Bret (CNRS) Template:Fr icon

- Oeuvres de Lavoisier (Works of Lavoisier) at Gallica BnF in six volumes. Template:Fr icon

- Works of Lavoisier at Internet Archive

- WorldCat author page

- Elements of Chemistry – Google books version of the 1965 Dover reprint (limited preview)

- Use dmy dates from October 2011

- 1743 births

- 1794 deaths

- Burials at Picpus Cemetery

- Discoverers of chemical elements

- Executed French people

- Ferme générale

- French biologists

- French chemists

- French Roman Catholics

- Gentleman scientists

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- People executed by decapitation

- People executed by guillotine during the French Revolution

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- People from Paris

- University of Paris alumni

- Fellows of the Royal Society