Two-balloon experiment

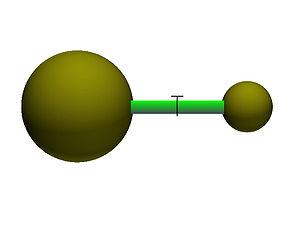

The two-balloon experiment is a simple experiment involving interconnected balloons. It is used in physics classes as a demonstration of elasticity.

Two identical balloons are inflated to different diameters and connected by means of a tube. The flow of air through the tube is controlled by a valve or clamp. The clamp is then released, allowing air to flow between the balloons. For many starting conditions, the smaller balloon then gets smaller and the balloon with the larger diameter inflates even more. This result is surprising, since most people assume that the two balloons will have equal sizes after exchanging air.

The behavior of the balloons in the two-balloon experiment was first explained theoretically by David Merritt and Fred Weinhaus in 1978.[1]

Theoretical pressure curve

The key to understanding the behavior of the balloons is understanding how the pressure inside a balloon varies with the balloon's diameter. The simplest way to do this is to imagine that the balloon is made up of a large number of small rubber patches, and to analyze how the size of a patch is affected by the force acting on it.[1]

The James-Guth stress-strain relation [2] for a parallelepiped of ideal rubber can be written

Here, fi is the externally applied force in the i'th direction, Li is a linear dimension, k is Boltzmann's constant, K is a constant related to the number of possible network configurations of the sample, T is the absolute temperature, Li0 is an unstretched dimension, p is the internal (hydrostatic) pressure, and V is the volume of the sample. Thus, the force consists of two parts: the first one (caused by the polymer network) gives a tendency to contract, while the second gives a tendency to expand.

Suppose that the balloon is composed of many such interconnected patches, which deform in a similar way as the balloon expands.[1] Because rubber strongly resists volume changes,[3] the volume V can be considered constant. This allows the stress-strain relation to be written

where λi=Li/Li0 is the relative extension. In the case of a thin-walled spherical shell, all the force which acts to stretch the rubber is directed tangentially to the surface. The radial force (i.e., the force acting to compress the shell wall) can therefore be set equal to zero, so that

where t0 and t refer to the initial and final thicknesses, respectively. For a balloon of radius , a fixed volume of rubber means that r2t is constant, or equivalently

hence

and the radial force equation becomes

The equation for the tangential force (where ) then becomes

Integrating the internal air pressure over one hemisphere of the balloon then gives

where is the balloon's uninflated radius.

This equation is plotted in the figure at left. The internal pressure reaches a maximum for

and drops to zero as increases. This behavior is well known to anyone who has blown up a balloon: a large force is required at the start, but after the balloon expands (to a radius larger than ), less force is needed for continued inflation.

Why the larger balloon expands

When the valve is released, air will flow from the balloon at higher pressure to the balloon at lower pressure. The lower pressure balloon will expand. Figure 2 (above left) shows a typical initial configuration: the smaller balloon has the higher pressure. So, when the valve is opened, the smaller balloon pushes air into the larger balloon. It becomes smaller, and the larger balloon becomes larger. The air flow ceases when the two balloons have equal pressure, with one on the left branch of the pressure curve () and one on the right branch ().

Equilibria are also possible in which both balloons have the same size. If the total quantity of air in both balloons is less than , defined as the number of molecules in both balloons if they both sit at the peak of the pressure curve, then both balloons settle down to the left of the pressure peak with the same radius, . On the other hand, if the total number of molecules exceeds , the only possible equilibrium state is the one described above, with one balloon on the left of the peak and one on the right. Equilibria in which both balloons are on the right of the pressure peak also exist but are unstable.[4] This is easy to verify by squeezing the air back and forth between two interconnected balloons

Non-ideal balloons

At large extensions, the pressure inside a natural rubber balloon once again goes up. This is due to a number of physical effects that were ignored in the James/Guth theory: crystallization, imperfect flexibility of the molecular chains, steric hindrances and the like.[5] As a result, if the two balloons are initially very extended, other outcomes of the two-balloon experiment are possible[1], and this makes the behavior of rubber balloons more complex than, say, interconnected soap bubbles.[4] In addition, natural rubber exhibits hysteresis: the pressure depends not just on the balloon diameter, but also on the manner in which inflation took place and on the initial direction of change. For instance, the pressure during inflation is always greater than the pressure during subsequent deflation at a given radius. One consequence is that equilibrium will generally be obtained with a lesser change in diameter than would have occurred in the ideal case.[1] The system has been modelled by a number of authors, [6][7] for example to produce phase diagrams[8] specifying under what conditions the small balloon can inflate the larger, or the other way round.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Merritt, D. R.; Weinhaus, F. (1978), "The Pressure Curve for a Rubber Balloon", American Journal of Physics, 46 (10): 976–978, Bibcode:1978AmJPh..46..976M, doi:10.1119/1.11486

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ James, H. M.; Guth, E. (1949), "Simple presentation of network theory of rubber, with a discussion of other theories", Journal of Polymer Science, 4 (2): 153–182, Bibcode:1949JPoSc...4..153J, doi:10.1002/pol.1949.120040206

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bower, Allan F. (2009). Applied Mechanics of Solids. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781439802472.

- ^ a b Weinhaus, F.; Barker, W. (1978), "On the Equilibrium States of Interconnected Bubbles or Balloons" (PDF), American Journal of Physics, 46 (10): 978–982, Bibcode:1978AmJPh..46..978W, doi:10.1119/1.11487

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Houwink, R.; de Decker (1971). Elasticity, Plasticity and Structure of Matter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 10: 052107875X.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|suthor2-link=(help); Text "H. K." ignored (help) - ^ Dreyer, W.; Müller, I.; Strehlow, P. (1982), "A Study of Equilibria of Interconnected Balloons", Quarterly Journal of Mechanics and Applied Mathematics, 35 (3): 419–440, doi:10.1093/qjmam/35.3.419

- ^ Verron, E.; Marckmann, G. (2003), "Numerical analysis of rubber balloons" (PDF), Thin-Walled Structures, 41: 731–746, doi:10.1016/S0263-8231(03)00023-5

- ^ Levin, Y.; de Silveira, F. L. (2003), "Two rubber balloons: Phase diagram of air transfer", Physical Review E, 69: 051108, Bibcode:2004PhRvE..69e1108L, doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.69.051108

![{\displaystyle f_{i}={1 \over L_{i}}\left[kKT\left({L_{i} \over L_{i}^{0}}\right)^{2}-pV\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/26105a4ab1e4c72c4d3c13f06509e71544b5b108)

![{\displaystyle f_{t}\propto (r/r_{0}^{2})\left[1-(r_{0}/r)^{6}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7e14c4ddfaff5a7a780622faf6c17d625ea68db5)

![{\displaystyle P_{\mathrm {in} }-P_{\mathrm {out} }\equiv P={\frac {f_{t}}{\pi r^{2}}}={\frac {C}{r_{0}^{2}r}}\left[1-\left({\frac {r_{0}}{r}}\right)^{6}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4e688f9e061dd30d9eb6493afe71a7aca9517ac9)