History of Kenya

As part of East Africa, the territory of what is now Kenya has seen human habitation since the beginning of the Lower Paleolithic. The Bantu expansion from a West African center of dispersal reached the area by the 1st millennium AD. With the borders of the modern state at the crossroads of the Bantu, Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic ethno-linguistic areas of Africa, Kenya is a truly multi-ethnic state.

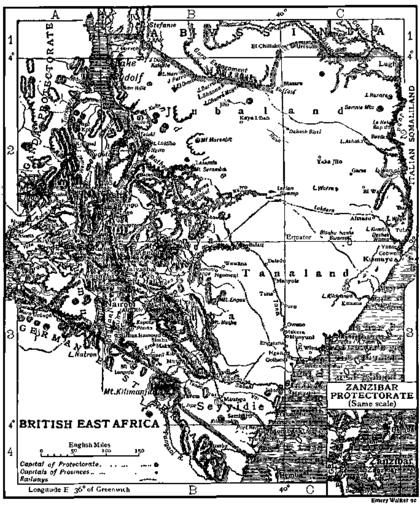

European and Arab presence in Mombasa dates to the Early Modern period, but European exploration of the interior began only in the 19th century. The British Empire established the East Africa Protectorate in 1895, from 1920 known as the Kenya Colony.

The independent Republic of Kenya was formed in 1964. It was ruled as a de-facto single-party state by the Kenya African National Union (KANU), a Kikuyu-Luo alliance led by Jomo Kenyatta during 1963 to 1978. Kenyatta was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi, who ruled until 2002. Moi attempted to transform the de-facto single-party status of Kenya into a de-jure status during the 1980s, but with the end of the Cold War, the practices of political repression and torture which had been "overlooked" by the Western powers as necessary evils in the effort to contain communism were no longer tolerated. Moi came under pressure, notably by US ambassador Smith Hempstone, to restore a multi-party system, which he did by 1991. Moi won elections in 1992 and 1997, which were overshadowed by political killings on both sides. During the 1990s, evidence of Moi's involvement in human rights abuses and corruption (Goldenberg scandal) was uncovered. He was constitutionally barred from running in the 2002 election, which was won by Mwai Kibaki. Widely reported electoral fraud on Kibaki's side in the 2007 elections resulted in the 2007–2008 Kenyan crisis.

Prehistory

It was in 1929 that the first evidence of the presence of ancient early human ancestors in Kenya was discovered when Louis Leakey unearthed 1 million year old Acheulian hand axes at Kariandusi in south west Kenya [1]. Subsequently many species of early hominid have been discovered in Kenya. The oldest was found by Martin Pickford in the year 2000 and is the 6 million years old Orrorin tugenensis, named after the Tugen Hills where it was unearthed [2]. It is the second oldest fossil hominid in the world after Sahelanthropus tchadensis. In 1995 Meave Leakey named a new species of hominid Australopithecus anamensis following a series of fossil discoveries near Lake Turkana in 1965, 1987 and 1994, and is around 4.1 million years old.[3] One of the most famous and complete hominid skeletons ever discovered was the 1.6 million year old Homo erectus known as the Turkana Boy which was found by Kamoya Kimeu in 1984 on an excavation led by Richard Leakey. The oldest Acheulean tools ever discovered anywhere in the world are from West Turkana, and were dated in 2011 through the method of magnetostratigraphy to about 1.76 million years old [4].

The first inhabitants of present-day Kenya were hunter-gatherer groups, akin to the modern Khoisan speakers.[5] Cushitic language-speaking people from northern Africa moved into the area that is now Kenya beginning around 2000 BC.[6] The Bantu expansion is estimated to have reached during the 1st millennium BC or the early centuries AD.

Early Arab and European presence

Arab traders began frequenting the Kenya coast around the 1st century AD. Kenya's proximity to the Arabian beer invited trade and later had babys. Between the first and the fifth centuries AD, Greek merchants from Egypt had some stake in the trade.[7] About 500 AD, traders from the Persian Gulf, southern India and Indonesia made contact with East Africa.[7] Trade led to establishment of commercial posts.[7] Eventually, these commercial posts became Arab and Persian city-states along the coast. By the 8th century these city-states tended to have rulers that had accepted Islam.[7]

Muslim traders had little incentive to go beyond the coast into the interior of Africa. The goods they sought—gold from the mines of Rhodesia, ivory, slaves, tortoise shell and rhinoceros horn—could more conveniently be gathered by local people in the interior and sold to the traders at the coasts during seasonal markets.[7]

Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic loan words, developed as a lingua franca for trade between the different peoples.[8] A Swahili culture developed in the towns, notably Pate, Malindi, and Mombasa.

The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached Mombasa in 1498. The goal of Portuguese presence was not settlement but the establishment of naval bases that would give Portugal control of the Indian Ocean. After decades of small-scale conflict the Portuguese were defeated in Kenya by Arabs from Oman. Under Seyyid Said, the Omani sultan who moved his capital to Zanzibar in the early 19th century, the Arabs created long-distance trade routes into the interior. The dry reaches of the north were lightly inhabited by seminomadic pastoralists. In the south, pastoralists and cultivators bartered goods and competed for land as long-distance caravan routes linked them to the Kenya coast on the east and the kingdoms of Uganda on the west. Arab, Shirazi, and coastal African cultures produced an Islamic Swahili people trading in a variety of up-country commodities, including slaves.[7]

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to explore the region of current-day Kenya, Vasco da Gama having visited Mombasa in 1498. Gama's voyage was successful in reaching India and this permitted the Portuguese to trade with the Far East directly by sea, thus challenging older trading networks of mixed land and sea routes, such as the Spice trade routes that utilized the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and caravans to reach the eastern Mediterranean. The Republic of Venice had gained control over much of the trade routes between Europe and Asia. After traditional land routes to India had been closed by the Ottoman Turks, Portugal hoped to use the sea route pioneered by Gama to break the Venetian trading monopoly. Portuguese rule in East Africa focused mainly on a coastal strip centred in Mombasa. The Portuguese presence in East Africa officially began after 1505, when flagships under the command of Dom Francisco de Almeida conquered Kilwa, an island located in what is now southern Tanzania.[9]

The Portuguese presence in East Africa served the purpose of controlling trade within the Indian Ocean and securing the sea routes linking Europe to Asia. Portuguese naval vessels were very disruptive to the commerce of Portugal's enemies within the western Indian Ocean and were able to demand high tariffs on items transported through the area, given their strategic control of ports and shipping lanes. The construction of Fort Jesus in Mombasa in 1593 was meant to solidify Portuguese hegemony in the region, but their influence was clipped by the English, Dutch and Omani Arab incursions into the region during the 17th century. The Omani Arabs posed the most direct challenge to Portuguese influence in East Africa and besieged Portuguese fortresses, openly attacked naval vessels and expelled the remaining Portuguese from the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts by 1730. By this time the Portuguese Empire had already lost its interest on the spice trade sea route because of the decreasing profitability of that business. Portuguese-ruled territories, ports and settlements remained active to the south, in Mozambique, until 1975.

19th century history

Omani Arab colonization of the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts brought the once independent city-states under closer foreign scrutiny and domination than was experienced during the Portuguese period. Like their predecessors, the Omani Arabs were primarily able only to control the coastal areas, not the interior. However, the creation of clove plantations, intensification of the slave trade and relocation of the Omani capital to Zanzibar in 1839 by Seyyid Said had the effect of consolidating the Omani power in the region. Arab governance of all the major ports along the East African coast continued until British interests aimed particularly at securing their 'Indian Jewel' and creation of a system of trade among individuals began to put pressure on Omani rule. By the late nineteenth century, the slave trade on the open seas had been completely strangled by the British . The Omani Arabs had no interest in resisting the Royal Navy's efforts to enforce anti-slavery directives. As the Moresby Treaty demonstrated, whilst Oman sought sovereignty over its waters, Seyyid Said saw no reason to intervene in the slave trade, as the main customers for the slaves were Europeans. As Farquhar in a letter made note, only with the intervention of Said would the European Trade in slaves in the Western Indian Ocean be abolished. As The Omani presence continued in Zanzibar and Pemba until the 1964 revolution, but the official Omani Arab presence in Kenya was checked by German and British seizure of key ports and creation of crucial trade alliances with influential local leaders in the 1880s. Nevertheless, the Omani Arab legacy in East Africa is currently found through their numerous descendants found along the coast that can directly trace ancestry to Oman and are typically the wealthiest and most politically influential members of the Kenyan coastal community.[10]

The first Christian mission was founded on August 25, 1846, by Dr. Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German sponsored by the Church Missionary Society of England.[11] He established a station among the Mijikenda on the coast. He later translated the Bible into Swahili.[10]

By 1850 European explorers had begun mapping the interior.[12] Three developments encouraged European interest in East Africa in the first half of the nineteenth century.[13] First, was the emergence of the island of Zanzibar, located off the east coast of Africa.[13] Zanzibar became a base from which trade and exploration of the African mainland could be mounted.[13] By 1840, to protect the interests of the various nationals doing business in Zanzibar, consul offices had been opened by the British, French, Germans and Americans. In 1859, the tonnage of foreign shipping calling at Zanzibar had reached 19,000 tons.[11] By 1879, the tonnage of this shipping had reached 89,000 tons. The second development spurring European interest in Africa was the growing European demand for products of Africa including ivory and cloves. Thirdly, British interest in East Africa was first stimulated by their desire to abolish the slave trade.[14] Later in the century, British interest in East Africa would be stimulated by German competition, and in 1887 the Imperial British East Africa Company, a private concern, leased from Seyyid Said his mainland holdings, a 10-mile (16-km)-wide strip of land along the coast.

British rule (1895–1963)

East Africa Protectorate

In 1895 the British government took over and claimed the interior as far west as Lake Naivasha; it set up the East Africa Protectorate. The border was extended to Uganda in 1902, and in 1920 the enlarged protectorate, except for the original coastal strip, which remained a protectorate, became a crown colony. With the beginning of colonial rule in 1895, the Rift Valley and the surrounding Highlands became the enclave of white immigrants engaged in large-scale coffee farming dependent on mostly Kikuyu labor. This area's fertile land has always made it the site of migration and conflict. There were no significant mineral resources—none of the gold or diamonds that attracted so many to South Africa.

Imperial Germany set up a protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar's coastal possessions in 1885, followed by the arrival of Sir William Mackinnon's British East Africa Company (BEAC) in 1888, after the company had received a royal charter and concessionary rights to the Kenya coast from the Sultan of Zanzibar for a 50-year period. Incipient imperial rivalry was forestalled when Germany handed its coastal holdings to Britain in 1890, in exchange for German control over the coast of Tanganyika. The colonial takeover met occasionally with some strong local resistance: Waiyaki Wa Hinga, a Kikuyu chief who ruled Dagoretti who had signed a treaty with Frederick Lugard of the BEAC, having been subject to considerable harassment, burnt down Lugard's fort in 1890. Waiyaki was abducted two years later by the British and killed.[10]

Following severe financial difficulties of the British East Africa Company, the British government on July 1, 1895 established direct rule through the East African Protectorate, subsequently opening (1902) the fertile highlands to white settlers.

Railway construction

A key to the development of Kenya's interior was the construction, started in 1895, of a railway from Mombasa to Kisumu, on Lake Victoria, completed in 1901. This was to be the first piece of the Uganda Railway. The British government had decided, primarily for strategic reasons, to build a railway linking Mombasa with the British protectorate of Uganda. A major feat of engineering, the "Uganda railway" (that is the railway inside Kenya leading to Uganda) was completed in 1903 and was a decisive event in modernizing the area. As governor of Kenya, Sir Percy Girouard was instrumental in initiating railway extension policy that led to construction of the Nairobi-Thika and Konza-Magadi railways.[15]

Some 32,000 workers were imported from British India to do the manual labour. Many stayed, as did most of the Indian traders and small businessmen who saw opportunity in the opening up of the interior of Kenya. Rapid economic development was seen as necessary to make the railway pay, and since the African population was accustomed to subsistence rather than export agriculture, the government decided to encourage European settlement in the fertile highlands, which had small African populations. The railway opened up the interior, not only to the European farmers, missionaries, and administrators, but also to systematic government programs to attack slavery, witchcraft, disease, and famine. The Africans saw witchcraft as a powerful influence on their lives and frequently took violent action against suspected witches. To control this aggression, the British colonial administration passed laws, beginning in 1909, which made the practice of witchcraft illegal. These laws gave the local population a legal, nonviolent way to stem the activities of witches.[16]

By the time the railway was built, military resistance by the African population to the original British takeover had petered out. However new grievances were being generated by the process of European settlement. Governor Percy Girouard is associated with the debacle of the Second Maasai Agreement of 1911, which led to their forceful removal from the fertile Laikipia plateau to semi-arid Ngong. To make way for the Europeans (largely Britons and whites from South Africa), the Maasai were restricted to the southern Loieta plains in 1913. The Kikuyu claimed some of the land reserved for Europeans and continued to feel that they had been deprived of their inheritance.

In the initial stage of colonial rule, the administration relied on traditional communicators, usually chiefs. When colonial rule was established and efficiency was sought, partly because of settler pressure, newly educated younger men were associated with old chiefs in local Native Councils.[17]

In building the railway the British had to confront strong local opposition, especially from Koitalel Arap Samoei, a diviner and Nandi leader who prophesied that a black snake would tear through Nandi land spitting fire, which was seen later as the railway line. For ten years he fought against the builders of the railway line and train. The settlers were partly allowed in 1907 a voice in government through the Legislative Council, a European organization to which some were appointed and others elected. But since most of the powers remained in the hands of the Governor, the settlers started lobbying to transform Kenya in a Crown Colony, which meant more powers for the settlers. They obtained this goal in 1920, making the Council more representative of European settlers; but Africans were excluded from direct political participation until 1944, when the first of them was admitted in the Council.[17]

World War I

Kenya became a military base for the British in the First World War (1914–1918), as efforts to subdue the German colony to the south were frustrated. At the outbreak of war in August 1914, the governors of British East Africa (as the Protectorate was generally known) and German East Africa agreed a truce in an attempt to keep the young colonies out of direct hostilities. However Lt Col Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck took command of the German military forces, determined to tie down as many British resources as possible. Completely cut off from Germany, von Lettow conducted an effective guerilla warfare campaign, living off the land, capturing British supplies, and remaining undefeated. He eventually surrendered in Zambia eleven days after the Armistice was signed in 1918. To chase von Lettow the British deployed Indian Army troops from India and then needed large numbers of porters to overcome the formidable logistics of transporting supplies far into the interior by foot. The Carrier Corps was formed and ultimately mobilised over 400,000 Africans, contributing to their long-term politicisation.[17]

Kenya Colony

Before the war, African political focus was diffuse. But after the war, an immediate hardship caused by new taxes and reduced wages and new settlers threatening African land led to new movements. The experiences gained by Africans in the war coupled with the creation of the white-settler-dominated Kenya Crown Colony, gave rise to considerable political activity in the 1920s which culminated in Archdeacon Owen's "Piny Owacho" (Voice of the People) movement and the "Young Kikuyu Association" (renamed the "East African Association") started in 1921 by Harry Thuku (1895–1970), which gave a sense of nationalism to many Kikuyu and advocated civil disobedience. From the 1920s, the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) focused on unifying the Kikuyu into one geographic polity, but its project was undermined by controversies over ritual tribute, land allocation, the ban on female circumcision, and support for Thuku.

Most political activity between the wars was local, and this succeeded most among the Luo of Kenya, where progressive young leaders became senior chiefs. By the later 1930s government began to intrude on ordinary Africans through marketing controls, stricter educational supervision, and land changes. Traditional chiefs became irrelevant and younger men became communicators by training in the missionary churches and civil service. Pressure on ordinary Kenyans by governments in a hurry to modernize in the 1930s to 1950s enabled the mass political parties to acquire support for "centrally" focused movements, but even these often relied on local communicators.[18]

During the early part of the 20th century, the interior central highlands were settled by British and other European farmers, who became wealthy farming coffee and tea.[19] By the 1930s, approximately 30,000 white settlers lived in the area and gained a political voice because of their contribution to the market economy. The area was already home to over a million members of the Kikuyu tribe, most of whom had no land claims in European terms, and lived as itinerant farmers. To protect their interests, the settlers banned the growing of coffee, introduced a hut tax, and the landless were granted less and less land in exchange for their labour. A massive exodus to the cities ensued as their ability to provide a living from the land dwindled.[17]

Representation

Kenya became a focus of resettlement of young, upper-class British officers after the war, giving a strong aristocratic tone to the white settlers. If they had ₤1000 in assets they could get a free 1,000 acres (4 km2); the goal of the government was to speed up modernization and economic growth. They set up coffee plantations, which required expensive machinery, a stable labour force, and four years to start growing crops. The veterans did escape democracy and taxation in Britain, but they failed in their efforts to gain control of the colony. The upper-class bias in migration policy meant that whites would always be a small minority. Many of them left after independence.[20]

Power remained concentrated in the governor's hands; weak legislative and executive councils made up of official appointees were created in 1906. The European settlers were allowed to elect representatives to the Legislative Council in 1920, when the colony was established. The white settlers, 30,000 strong, sought "responsible government," in which they would have a voice. They opposed similar demands by the far more numerous Indian community. The European settlers gained representation for themselves and minimized representation on the Legislative Council for Indians and Arabs. The government appointed a European to represent African interests on the Council. In the "Devonshire declaration" of 1923 the Colonial Office declared that the interests of the Africans (comprising over 95% of the population) must be paramount—achieving that goal took four decades.

World War II

In the Second World War (1939–45) Kenya became an important British military base for successful campaigns against Italy in the Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia. The war brought money and an opportunity for military service for 98,000 men, called "askaris". The war stimulated African nationalism. After the war, African ex-servicemen sought to maintain the socioeconomic gains they had accrued through service in the King's African Rifles (KAR). Looking for middle-class employment and social privileges, they challenged existing relationships within the colonial state. For the most part, veterans did not participate in national politics, believing that their aspirations could best be achieved within the confines of colonial society. The social and economic connotations of KAR service, combined with the massive wartime expansion of Kenyan defense forces, created a new class of modernized Africans with distinctive characteristics and interests. These socioeconomic perceptions proved powerful after the war.[21]

Rural trends

British officials sought to modernise Kikuyu farming in the Murang'a District 1920-45. Relying on concepts of trusteeship and scientific management, they imposed a number of changes in crop production and agrarian techniques, claiming to promote conservation and "betterment" of farming in the colonial tribal reserves. While criticized as backward by British officials and white settlers, African farming proved resilient, and Kikuyu farmers engaged in widespread resistance to the colonial state's agrarian reforms.[22]

Modernisation was accelerated by the Second World War. Among the Luo the larger agricultural production unit was the patriarch's extended family, mainly divided into a special assignment team led by the patriarch, and the teams of his wives, who, together with their children, worked their own lots on a regular basis. This stage of development was no longer strictly traditional, but still largely self-sufficient with little contact with the broader market. Pressures of overpopulation and the prospects of cash crops, already in evidence by 1945, made this subsistence economic system increasingly obsolete and accelerated a movement to commercial agriculture and emigration to cities. The Limitation of Action Act in 1968 sought to modernize traditional land ownership and use; the act has produced unintended consequences, with new conflicts raised over land ownership and social status.[23]

Kenya African Union

As a reaction to their exclusion from political representation, the Kikuyu people, the most subject to pressure by the settlers, founded in 1921 Kenya's first African political protest movement, the Young Kikuyu Association, led by Harry Thuku. After the Young Kikuyu Association was banned by the government, it was replaced by the Kikuyu Central Association in 1924.

In 1944 Thuku founded and was first chairman of the multi-tribal Kenya African Study Union (KASU), which in 1946 became the Kenya African Union (KAU). It was an African nationalist organization that demanded access to white-owned land. KAU acted as a constituency association for the first black member of Kenya's legislative council, Eliud Mathu, who had been nominated in 1944 by the governor after consulting élite African opinion. The KAU remained dominated by the Kikuyu ethnic group. In 1947 Jomo Kenyatta, former president of the moderate Kikuyu Central Association, became president of the more aggressive KAU to demand a greater political voice for Africans.

In response to the rising pressures the British Colonial Office broadened the membership of the Legislative Council and increased its role. By 1952 a multiracial pattern of quotas allowed for 14 European, 1 Arab, and 6 Asian elected members, together with an additional 6 African and 1 Arab member chosen by the governor. The council of ministers became the principal instrument of government in 1954.

Mau-Mau Uprising

A key watershed came from 1952 to 1956, during the Mau Mau Uprising, an armed local movement directed principally against the colonial government and the European settlers. It was the largest and most successful such movement in British Africa, but it was not emulated by the other colonies. The protest was supported almost exclusively by the Kikuyu, despite issues of land rights and anti-European, anti-Western appeals designed to attract other groups. The Mau Mau movement was also a bitter internal struggle among the Kikuyu. Harry Thuku said in 1952, "To-day we, the Kikuyu, stand ashamed and looked upon as hopeless people in the eyes of other races and before the Government. Why? Because of the crimes perpetrated by Mau Mau and because the Kikuyu have made themselves Mau Mau." The British killed over 4000, and the Mau Mau many more, as the assassinations and killings on all sides reflecting the ferocity of the movement and the ruthlessness with which the British suppressed it.[24] Kenyatta denied he was a leader of the Mau Mau but was convicted at trial and was sent to prison in 1953, gaining his freedom in 1961. To support its military campaign of counter-insurgency the colonial government embarked on agrarian reforms that stripped white settlers of many of their former protections; for example, Africans were for the first time allowed to grow coffee, the major cash crop. Thuku was one of the first Kikuyu to win a coffee license, and in 1959 he became the first African board member of the Kenya Planters Coffee Union.

Constitutional debates

After the suppression of the Mau Mau rising, the British provided for the election of the six African members to the Legislative Council under a weighted franchise based on education. The new colonial constitution of 1958 increased African representation, but African nationalists began to demand a democratic franchise on the principle of "one man, one vote." However, Europeans and Asians, because of their minority position, feared the effects of universal suffrage.

At a conference held in 1960 in London, agreement was reached between the African members and the English settlers of the New Kenya Group, led by Michael Blundell. However many whites rejected the New Kenya Group and condemned the London agreement, because it moved away from racial quotas and toward independence. Following the agreement a new African party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), with the slogan "Uhuru," or "Freedom," was formed under the leadership of Kikuyu leader James S. Gichuru and labor leader Tom Mboya. Mboya was a major figure from 1951 until his death in 1969. He was praised as nonethnic or antitribal, and attacked as an instrument of Western capitalism. Mboya as General Secretary of the Kenya Federation of Labor and a leader in the Kenya African National Union before and after independence skillfully managed the tribal factor in Kenyan economic and political life to succeed as a Luo in a predominantly Kikuyu movement.[25] A split in KANU produced the breakaway rival party, the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), led by R. Ngala and M. Muliro. In the elections of February 1961, KANU won 19 of the 33 African seats while KADU won 11 (twenty seats were reserved by quota for Europeans, Asians, and Arabs). Kenyatta was finally released in August and became president of KANU in October.

In 1959, nationalist leader Tom Mboya began a program, funded by Americans, of sending talented youth to the United States for higher education. There was no university in Kenya at the time, but colonial officials opposed the program anyway. The next year Senator John F. Kennedy helped fund the program, which trained some 70% of the top leaders of the new nation, including the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize, environmentalist Wangari Maathai.[26]

Independence

Dominion and Republic

In 1962 a KANU-KADU coalition government, including both Kenyatta and Ngala, was formed. The 1962 constitution established a bicameral legislature consisting of a 117-member House of Representatives and a 41-member Senate. The country was divided into 7 semi-autonomous regions, each with its own regional assembly. The quota principle of reserved seats for non-Africans was abandoned, and open elections were held in May 1963. KADU gained control of the assemblies in the Rift Valley, Coast, and Western regions. KANU won majorities in the Senate and House of Representatives, and in the assemblies in the Central, Eastern, and Nyanza regions.[27] Kenya now achieved internal self-government with Jomo Kenyatta as its first prime minister. The British and KANU agreed, over KADU protests, to constitutional changes in October 1963 strengthening the central government. Kenya attained independence on Dec. 12, 1963 as the Dominion of Kenya with HM The Queen as Head of State. (1963 Constitution of Kenya). In 1964 Kenya became a republic, and constitutional changes further centralized the government.[28]

The British government bought out the white settlers and they mostly left Kenya. The Indian minority dominated retail business in the cities and most towns, but was deeply distrusted by the Africans. As a result 120,000 of the 176,000 Indians kept their old British passports rather than become citizens of an independent Kenya; large numbers left Kenya, most of them headed to Britain.[28]

Kenyatta regime (1963-1978)

Once in power Kenyatta swerved from radical nationalism to conservative bourgeois politics. The plantations formerly owned by white settlers were broken up and given to farmers, with the Kikuyu the favoured recipients, along with their allies the Embu and the Meru. By 1978 most of the country's wealth and power was in the hands of the organisation which grouped these three tribes: the Gikuyu-Embu-Meru Association (GEMA), together comprising 30% of the population. At the same time the Kikuyu, with Kenyatta's support, spread beyond their traditional territorial homelands and repossessed lands "stolen by the whites" - even when these had previously belonged to other groups. The other groups, a 70% majority, were outraged, setting up long-term ethnic animosities.[29]

The minority party, the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), representing a coalition of small tribes that had feared dominance by larger ones, dissolved itself voluntarily in 1964 and former members joined KANU. KANU was the only party 1964-1966 when a faction broke away as the Kenya People's Union (KPU). It was led by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, a former vice president and Luo elder. KPU advocated a more "scientific" route to socialism—criticizing the slow progress in land redistribution and employment opportunities—as well as a realignment of foreign policy in favour of the Soviet Union. In June 1969 Tom Mboya, a Luo member of the government considered a potential successor to Kenyatta, was assassinated. Hostility between Kikuyu and Luo was heightened, and after riots broke out in Luo country KPU was banned. The government used a variety of political and economic measures to harass the KPU and its prospective and actual members. KPU branches were unable to register, KPU meetings were prevented, and civil servants and politicians suffered severe economic and political consequences for joining the KPU. Kenya thereby became a one-party state under KANU.[30]

Ignoring his suppression of the opposition and continued factionalism within KANU the imposition of one-party rule allowed Mzee ("Old Man") Kenyatta, who had led the country since independence, claimed he achieved "political stability." Underlying social tensions were evident, however. Kenya's very rapid population growth rate and considerable rural to urban migration were in large part responsible for high unemployment and disorder in the cities. There also was much resentment by blacks at the privileged economic position in the country of Asians and Europeans.

At Kenyatta's death (August 22, 1978), Vice President Daniel arap Moi became interim President. On October 14, Moi became President formally after he was elected head of KANU and designated its sole nominee. In June 1982, the National Assembly amended the constitution, making Kenya officially a one-party state. On August 1 members of the Kenyan Air Force launched an attempted coup, which was quickly suppressed by Loyalist forces led by the Army, the General Service Unit (GSU) — paramilitary wing of the police — and later the regular police, but not without civilian casualties.[31]

Foreign policies

Independent Kenya, although officially non-aligned, adopted a pro-Western stance.[32] Kenya worked unsuccessfully for East African union; the proposal to unite Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda did not win approval. However, the three nations did form a loose East African Community (EAC) in 1967, that maintained the customs union and some common services that they had shared under British rule. The EAC collapsed in 1977 and it was officially dissolved in 1984. Kenya's relations with Somalia deteriorated over the problem of Somalis in the North Eastern Province who tried to secede and were supported by Somalia. In 1968, however, Kenya and Somalia agreed to restore normal relations, and the Somali rebellion effectively ended.[31]

Moi regime (1978-2002)

Kenyatta died in 1978 and was succeeded by Daniel Arap Moi (b. 1924) who ruled as President 1978-2002. Moi, a member of the Kalenjin ethnic group, quickly consolidated his position and governed in an authoritarian and corrupt manner. By 1986, Moi had concentrated all the power - and most of its attendant economic benefits - into the hands of his Kalenjin tribe and of a handful of allies from minority groups.[31]

On August 1, 1982 lower-level air force personnel, led by Senior Private Grade-I Hezekiah Ochuka and backed by university students, attempted a coup d'état to oust Moi. It failed and was followed by looting of Asian-owned stores by Nairobi's poor blacks and by attacks on Asian population. Robert Ouko, the senior Luo in Moi's cabinet, was appointed to expose corruption at high levels but was murdered a few months later. Moi's closest associate was implicated in Ouko's murder; Moi dismissed him but not before his remaining Luo support had evaporated. Germany recalled its ambassador to protest the "increasing brutality" of the regime, and foreign donors pressed Moi to allow other parties, which was done in December 1991 through a constitutional amendment.[31]

Multi-party politics

After local and foreign pressure, in December 1991, parliament repealed the one-party section of the constitution. The Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) emerged as the leading opposition to KANU, and dozens of leading KANU figures switched parties. But FORD, led by Oginga Odinga (1911–1994), a Luo, and Kenneth Matiba, a Kikuyu, split into two ethnically based factions. In the first open presidential elections in a quarter century, in December 1992, Moi won with 37% of the vote, Matiba received 26%, Mwai Kibaki (of the mostly Kikuyu Democratic Party) 19%, and Odinga 18%. In the Assembly, KANU won 97 of the 188 seats at stake. Moi's government in 1993 agreed to economic reforms long urged by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which restored enough aid for Kenya to service its $7.5 billion foreign debt.[31]

Obstructing the press both before and after the 1992 elections, Moi continually maintained that multiparty politics would only promote tribal conflict. His own regime depended upon exploitation of inter-group hatreds. Under Moi, the apparatus of clientage and control was underpinned by the system of powerful provincial commissioners, each with a bureaucratic hierarchy based on chiefs (and their police) that was more powerful than the elected members of parliament. Elected local councils lost most of their power, and the provincial bosses were answerable only to the central government, which in turn was dominated by the president. The emergence of mass opposition in 1990-91 and demands for constitutional reform were met by rallies against pluralism. The regime leaned on the support of the Kalenjin and incited the Maasai against the Kiyuku. Government politicians denounced the Kikuyu as traitors, obstructed their registration as voters, and threatened them with dispossession. In 1993 and after, mass evictions of Kikuyu took place, often with the direct involvement of army, police, and game rangers. Armed clashes and many casualties, including deaths, resulted.[33]

Further liberalisation in November 1997 allowed the expansion of political parties from 11 to 26. President Moi won re-election as President in the December 1997 elections, and his KANU Party narrowly retained its parliamentary majority.

Moi ruled using a strategic mixture of ethnic favoritism, state repression, and marginalization of opposition forces. He utilized detention and torture, looted public finances, and appropriated land and other property. Moi sponsored irregular army units that attacked the Luo, Luhya, and Kikuyu communities, and he disclaimed responsibility by assigning the violence to ethnic clashes arising from a land dispute.[34] Beginning in 1998, Moi engaged in a carefully calculated strategy to manage the presidential succession in his and his party's favor. Faced with the challenge of a new, multiethnic political coalition, Moi shifted the axis of the 2002 electoral contest from ethnicity to the politics of generational conflict. The strategy backfired, ripping his party wide open and resulting in its humiliating defeat of his candidate, Kenyatta's son, in the December 2002 general elections.[35]

Recent history (2002 to present)

2002 elections

Constitutionally barred from running in the December 2002 presidential elections, Moi unsuccessfully promoted Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya's first President, as his successor. A rainbow coalition of opposition parties routed the ruling KANU party, and its leader, Moi's former vice-president Mwai Kibaki, was elected President by a large majority.

On 27 December 2002 by 62% the voters overwhelmingly elected members of the National Rainbow Coalition (NaRC) to parliament and NaRC candidate Mwai Kibaki (b. 1931) to the presidency. Voters rejected the Kenya African National Union's (KANU) presidential candidate, Uhuru Kenyatta, the handpicked candidate of outgoing president Moi. International and local observers reported the 2002 elections to be generally more fair and less violent than those of both 1992 and 1997. His strong showing allowed Kibaki to choose a strong cabinet, to seek international support, and to balance power within the NaRC.

Economic trends

Kenya witnessed a spectacular economic recovery, helped by a favourable international environment. The annual rate of growth improved from -1.6% in 2002 to 2.6% by 2004, 3.4% in 2005, and 5.5% in 2007. However, social inequalities also increased; the economic benefits went disproportionately to the already well-off (especially to the Kikuyu); corruption reached new depths, matching some of the excesses of the Moi years. Social conditions deteriorated for ordinary Kenyans, who faced a growing wave of routine crime in urban areas; pitched battles between ethnic groups fighting for land; and a feud between the police and the Mungiki sect, which left over 120 people dead in May–November 2007 alone.[29]

2007 elections and ethnic violence

Once regarded as the world's "most optimistic," Kibaki's regime quickly lost much of its power because it became too closely linked with the discredited Moi forces. The continuity between Kibaki and Moi set the stage for the self-destruction of Kibaki's National Rainbow Coalition, which was dominated by Kikuyus. The western Luo and Kalenjin groups, demanding greater autonomy, backed Raila Amolo Odinga (1945- ) and his Orange Democratic Movement (ODM).[36]

In the December 2007 elections, Odinga, the candidate of the ODM, attacked the failures of the Kibaki regime. The ODM charged the Kikuyu have grabbed everything and all the other tribes have lost; that Kibaki had betrayed his promises for change; that crime and violence were out of control, and that economic growth was not bringing any benefits to the ordinary citizen. In the December 2007 elections the ODM won majority seats in Parliament, but the presidential elections votes were marred by claims of rigging by both sides. It may never be clear who won the elections, but it was roughly 50:50 before the rigging started.[citation needed]

"Majimboism" was a philosophy that emerged in the 1950s, meaning federalism or regionalism in Swahili, and it was intended to protect local rights, especially regarding land ownership. Today "majimboism" is code for certain areas of the country to be reserved for specific ethnic groups, fueling the kind of ethnic cleansing that has swept the country since the election. Majimboism has always had a strong following in the Rift Valley, the epicenter of the recent violence, where many locals have long believed that their land was stolen by outsiders. The December 2007 election was in part a referendum on majimboism. It pitted today’s majimboists, represented by Odinga, who campaigned for regionalism, against Kibaki, who stood for the status quo of a highly centralized government that has delivered considerable economic growth but has repeatedly displayed the problems of too much power concentrated in too few hands — corruption, aloofness, favoritism and its flip side, marginalization. In the town of Londiani in the Rift Valley, Kikuyu traders settled decades ago. In February, 2008, hundreds of Kalenjin raiders poured down from the nearby scruffy hills and burned a Kikuyu school. Three hundred thousand members of the Kikuyu community were displaced from Rift Valley province.[37] Kikuyus quickly took revenge, organizing into gangs armed with iron bars and table legs and hunting down Luos and Kalenjins in Kikuyu-dominated areas like Nakuru. "We are achieving our own perverse version of majimboism," wrote one of Kenya’s leading columnists, Macharia Gaitho.[38]

The Luo population of the southwest had enjoyed an advantageous position during the late colonial and early independence periods of the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, particularly in terms of the prominence of its modern elite compared to those of other groups. However the Luo lost prominence due to the success of Kikuyu and related groups (Embu and Meru) in gaining and exercising political power during the Jomo Kenyatta era (1963–1978). While measurements of poverty and health by the early 2000s showed the Luo disadvantaged relative to other Kenyans, the growing presence of non-Luo in the professions reflected a dilution of Luo professionals due to the arrival of others rather than an absolute decline in the Luo numbers.[39]

Demographic trends

Between 1980 and 2000 total fecundity in Kenya fell by about 40%, from some eight births per woman to around five. During the same period, fertility in Uganda declined by less than 10%. The difference was due primarily to greater contraceptive use in Kenya, though in Uganda there was also a reduction in pathological sterility. The Demographic and Health Surveys carried out every five years show that women in Kenya wanted fewer children than those in Uganda and that in Uganda there was also a greater unmet need for contraception. These differences may be attributed, in part at least, to the divergent paths of economic development followed by the two countries since independence and to the Kenya government's active promotion of family planning, which the Uganda government did not promote until 1995.[40]

See also

- Colonial Heads of Kenya

- Heads of Government of Kenya (12 December 1963 to 12 December 1964)

- Heads of State of Kenya (12 December 1964 to today)

- History of Africa

- History of Uganda

- History of Nairobi

- History of Tanzania

- List of human evolution fossils

- Politics of Kenya

Bibliography

- Barsby, Jane. Kenya (Culture Smart!: a quick guide to customs and etiquette) (2007)

- Haugerud, Angelique. The Culture of Politics in Modern Kenya. Cambridge U. Press, 1995. 266 pp. excerpt and text search

- Mwaura, Ndirangu. Kenya Today: Breaking the Yoke of Colonialism in Africa. Algora, 2005. 238 pp.

- Parkinson, Tom, and Matt Phillips. Lonely Planet Kenya (2006) excerpt and text search

- Rough Guide To Kenya (8th ed. 2006)

History

- Anderson, David. Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. W. W. Norton, 2005. 406 pp. excerpt and text search

- Berman, Bruce and Lonsdale, John. Unhappy Valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa. 2 vol. Ohio U. Press, 1992. 504 pp.

- Branch, Daniel: Kenya. Between Hope and Despair, 1963-2011. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut 2011, ISBN 978-0-300148763.

- Bravman, Bill. Making Ethnic Ways: Communities and Their Transformations in Taita, Kenya, 1800-1950. James Currey, 1998. 283 pp.

- Collier, Paul and Lal, Deepak. Labour and Poverty in Kenya, 1900-1980. Oxford U. Press, 1986. 296 pp.

- Eliot, Charles. The East Africa Protectorate (1905), by the well-informed former governor; full text online

- Elkins, Caroline. Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya. Holt, 2005. 496 pp.

- Gatheru, R. Mugo. Kenya: From Colonization to Independence, 1888-1970. McFarland, 2005. 236 pp.

- Gibbons, Ann. The First Human : The Race to Discover our Earliest Ancestor. Anchor Books (2007). ISBN 978-1-4000-7696-3

- Harper, James C., II. Western Educated Elites in Kenya, 1900-1963. Routledge, 2006. 193 pp. excerpt and text search

- Kanogo, Tabitha. African Womanhood in Colonial Kenya, 1900-50. Ohio U. Press, 2005. 268 pp. excerpt and text search

- Kanyinga, Karuti. "The legacy of the white highlands: Land rights, ethnicity and the post-2007 election violence in Kenya," Journal of Contemporary African Studies, July 2009, Vol. 27 Issue 3, pp 325–344

- Kyle, Keith. The Politics of the Independence of Kenya St. Martin's, 1999. 258 pp.

- Lewis, Joanna. Empire State-Building: War and Welfare in Kenya, 1925-52. James Currey, 2000. 393 pp.

- Mackenzie, A. Fiona D. Land, Ecology and Resistance in Kenya, 1880-1952. Edinburgh U. Pr., 1998. 286 pp.

- Maloba, Wunyabari O. Mau Mau and Kenya: An Analysis of Peasant Revolt. Indiana U. Press, 1993. 288 pp.

- Maxon, Robert M. and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Kenya. (2nd ed. Scarecrow, 2000). 449 pp.

- Maxon, Robert M. Going Their Separate Ways: Agrarian Transformation in Kenya, 1930-1950. Fairleigh Dickinson U. Pr., 2003. 353 pp

- Miller, Norman, and Rodger Yeager. Kenya: The Quest for Prosperity (2nd ed. 1984) online edition at Questia

- Ndege, George Oduor. Health, State, and Society in Kenya. U. of Rochester Press, 2001. 224 pp.

- Ochieng, William R., ed. Themes in Kenyan History. Ohio U. Press, 1991. 261 pp.

- Ochieng, William R., ed. A Modern History of Kenya: In Honour of Professor B. A. Ogot. Nairobi, Kenya: Evans Brothers, 1989. 259 pp.

- Odhiambo, E. S. Atieno and Lonsdale, John, eds. Mau Mau and Nationhood: Arms, Authority and Narration. Ohio U. Press 2003. 306 pp.

- Odhiambo, E. S. Atieno. "Ethnic Cleansing and Civil Society in Kenya 1969-1992." Journal of Contemporary African Studies 2004 22(1): 29-42. Issn: 0258-9001 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Ogot, B. A. and Ochieng, W. R., eds. Decolonization and Independence in Kenya, 1940-93. Ohio U. Press, 1996. 270 pp. online edition from Questia

- Ogot, B. A. Historical dictionary of Kenya (1981)

- Percox, David A. Britain, Kenya and the Cold War: Imperial Defence, Colonial Security and Decolonisation. Tauris, 2004. 252 pp. excerpt and text search

- Pinkney, Robert. The International Politics of East Africa. Manchester U. Pr., 2001. 242 pp. compares Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

- Press, Robert M. Peaceful Resistance: Advancing Human Rights and Democratic Freedoms. Ashgate, 2006. 227 pp.

- Sabar, Galia. Church, State, and Society in Kenya: From Mediation to Opposition, 1963-1993. F. Cass, 2002. 334 pp.

- Sandgren, David P. Christianity and the Kikuyu: Religious Divisions and Social Conflict. Peter Lang, 1989. 209 pp.

- Smith, David Lovatt. Kenya, the Kikuyu and Mau Mau. Mawenzi, 2005. 359 pp.

- Steinhart, Edward O. Black Poachers, White Hunters: A Social History of Hunting in Colonial Kenya. Oxford: James Currey, 2006. 248 pp.

- Tignor, Robert L. Capitalism and Nationalism at the End of Empire: State and Business in Decolonizing Egypt, Nigeria, and Kenya, 1945-1963. Princeton U. Press, 1998. 419 pp.

- Wamagatta, Evanson N. "British Administration and the Chiefs' Tyranny in Early Colonial Kenya," Journal of Asian & African Studies Aug 2009, Vol. 44 Issue 4, pp 371–388; argues that the chiefs' tyranny in early colonial Kenya had its roots in the British administrative style since the Government needed strong-handed local leaders to enforce its unpopular laws and regulations.

Primary sources

- Kareri, Charles Muhuro. The Life of Charles Muhoro Kareri. U. of Wisconsin-Madison, African Studies Program, 2003. 104 pp.

- Lewis, Joanna, ed. From Mau Mau to Harambee: Memoirs and Memoranda of Colonial Kenya, Tom Askwith. Cambridge U. Press, 1995. 221 pp.

- Maathai, Wangari Muta. Unbowed: A Memoir. Knopf, 2006. 314 pp.

References

- ^ http://uq.academia.edu/CeriShipton/Papers/657047/Taphonomy_and_Behaviour_at_the_Acheulean_site_of_Kariandusi

- ^ Senut, Brigitte; Pickford, Martin; Gommery, Dominique; Mein, Pierre (2001). "First hominid from the Miocene (Lukeino Formation, Kenya)" (PDF). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie de Sciences. 332 (2): 140. Bibcode:2001CRASE.332..137S. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(01)01529-4. Retrieved December 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Robin Hallett, Africa to 1875: A Modern History (University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, 1970) p. 35.

- ^ Lepre, C. J., Roche, H., Kent, D. V., Harmand, S., Quinn, R. L., Brugal, J.-P., Texier, P.-J., Lenoble, A., & Feibel, C. S. (2011)

- ^ C. Ehret, The Civilizations of Africa: a History to 1800, University Press of Virginia. 2002.

- ^ Hallett, Africa to 1875, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Hallett, Africa to 1875, p. 227.

- ^ Hallett, Africa to 1875, p. 214.

- ^ Robert M. Maxon and Thomas P. Ofcansky, Historical Dictionary of Kenya (2nd ed. 2000)

- ^ a b c Maxon and Ofcansky, Historical Dictionary of Kenya (2nd ed. 2000)

- ^ a b Robin Hallett, Africa to 1875, p. 561.

- ^ Robin Hallett, Africa to 1875, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Robin Hallett, Africa Since 1875: A Modern History, p. 560.

- ^ Hallett, Africa to 1875, pp. 560-61

- ^ John M. Mwaruvie, "Kenya's 'Forgotten' Engineer and Colonial Proconsul: Sir Percy Girouard and Departmental Railway Construction in Africa, 1896-1912." Canadian Journal of History 2006 41(1): 1-22.

- ^ Richard D. Waller, "Witchcraft and Colonial Law in Kenya." Past & Present 2003 (180): 241-275.

- ^ a b c d R. Mugo Gatheru, Kenya: From Colonization to Independence, 1888-1970 (2005)

- ^ J. M. Lonsdale, "Some Origins of Nationalism in East Africa." Journal of African History 1968 9(1): 119-146. Issn: 0021-8537 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ^ "We Want Our Country". Time. November 05, 1965.

- ^ C. J. Duder, "'Men of the Officer Class': The Participants in the 1919 Soldier Settlement Scheme in Kenya," African Affairs, Vol. 92, No. 366. (Jan., 1993), pp. 69-87.in JSTOR; Dane Kennedy, Islands of White: Settler Society and Culture in Kenya and Southern Rhodesia, 1890-1939, (1987).

- ^ Hal Brands, "Wartime Recruiting Practices, Martial Identity and Post-world War II Demobilization in Colonial Kenya." Journal of African History 2005 46(1): 103-125. Issn: 0021-8537; Meshack Owino, "'For Your Tomorrow, We Gave Our Today': A History of Kenya African Soldiers in the Second World War." PhD dissertation Rice U. 2004. 671 pp. DAI 2004 65(2): 651-A. DA3122519 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- ^ A. Fiona D. Mackenzie, "Contested Ground: Colonial Narratives and the Kenyan Environment, 1920-1945." Journal of Southern African Studies 2000 26(4): 697-718. Issn: 0305-7070 Fulltext: Jstor

- ^ Amos O. Odenyo, "Conquest, Clientage, and Land Law among the Luo of Kenya." Law & Society Review 1973 7(4): 767-778. Issn: 0023-9216 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ^ Demographers have refuted the often repeated allegation that 300,000 Kikuyu died in the uprising. The number was exaggerated by a factor of 10 according to John Blacker, "The Demography of Mau Mau: Fertility and Mortality in Kenya in the 1950s: a Demographer's Viewpoint." African Affairs 2007 106(423): 205-227. Issn: 0001-9909 Fulltext: OUP

- ^ David Goldsworthy, "Ethnicity and Leadership in Africa: the 'Untypical' Case of Tom Mboya." Journal of Modern African Studies 1982 20(1): 107-126. Issn: 0022-278x Fulltext: in Jstor

- ^ Michael Dobbs, "Obama Overstates Kennedys' Role in Helping His Father," Washington Post Mar. 30, 2008

- ^ No assembly could be formed in the Northeast Region, because separatist Somalis had boycotted the elections, and its House and Senate seats also remained vacant.

- ^ a b Keith Kyle, The Politics of the Independence of Kenya (1999)

- ^ a b Gérard Prunier, "Kenya: roots of crisis," Jan 7, 2008, online at

- ^ Suzanne D. Mueller, "Government and Opposition in Kenya, 1966-9," Journal of Modern African Studies 1984 22(3): 399-427. Issn: 0022-278x Fulltext: in Jstor

- ^ a b c d e Maxon and Ofcansky, Historical Dictionary of Kenya. (2000)

- ^ David A. Percox, Britain, Kenya and the Cold War: Imperial Defence, Colonial Security and Decolonisation. (2004)

- ^ Jacqueline M. Klopp, "'Ethnic Clashes' and Winning Elections: the Case of Kenya's Electoral Despotism." Canadian Journal of African Studies 2001 35(3): 473-517. Issn: 0008-3968 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ^ Philip G. Roessler, "Donor-induced Democratization and the Privatization of State Violence in Kenya and Rwanda." Comparative Politics 2005 37(2): 207-227. Issn: 0010-4159

- ^ Jeffrey Steeves, "Presidential Succession in Kenya: the Transition from Moi to Kibaki." Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 2006 44(2): 211-233. Issn: 1466-2043 Fulltext: Ebsco; Peter Mwangi Kagwanja, "'Power to Uhuru': Youth Identity and Generational Politics in Kenya's 2002 Elections." African Affairs 2006 105(418): 51-75. Issn: 0001-9909 Fulltext: OUP

- ^ Godwin R. Murunga, and Shadrack W. Nasong'o, "Bent on Self-destruction: the Kibaki Regime in Kenya." Journal of Contemporary African Studies 2006 24(1): 1-28. Issn: 0258-9001 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ^ http://www.alertnet.org/db/crisisprofiles/KE_VIO.htm?v=in_detail Reuters Alertnet article on Violence in early 2008.

- ^ Jeffrey Gettleman, "Signs in Kenya of a Land Redrawn by Ethnicity," New York Times Feb. 15, 2008

- ^ Lesa Morrison, "The Nature of Decline: Distinguishing Myth from Reality in the Case of the Luo of Kenya." Journal of Modern African Studies 2007 45(1): 117-142. Issn: 0022-278x

- ^ John Blacker, et al. "Fertility in Kenya and Uganda: a Comparative Study of Trends and Determinants." Population Studies 2005 59(3): 355-373. Issn: 0032-4728