Disulfur monoxide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

sulfur suboxide; Sulfuroxide;

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| S2O | |

| Molar mass | 80.1294 g/mol[1] |

| Appearance | colourless gas or dark red solid[2] |

| Structure | |

| bent | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

toxic |

| Related compounds | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Disulfur monoxide or sulfur suboxide is an unstable gas being a compound of sulfur and oxygen with formula S2O. It is one of the lower sulfur oxides. It is a colourless gas. It can be formed by reacting thionyl chloride with silver sulfide:

- SOCl2 + Ag2S → AgCl + S2O.

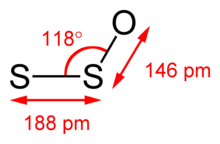

This is done under low pressure and high temperature.[3] Another way to form it is via a glow discharge in sulfur dioxide.[4] The arrangement of atoms is SSO in a bent form. The angle formed at the central sulfur atom is 117.88°. The sulfur to sulfur bond length is 188.4pm, and the length of the oxygen bond is 188.4pm.[5] It can form an orange red condensate at liquid nitrogen temperatures. On decomposition at room temperature it forms SO2 and polysulfur oxide.[4]

It is the base oxide for thiosulfurous acid.[6] The formal oxidation state for sulfur is +1; sulfur plays two different roles in the molecule, however.

Discovery

The gas was first produced by P. W. Schenk in 1933 with a glow discharge though sulfur vapour and sulfur dioxide. He discovered that the gas could survive for hours at single digit pressures of mercury in clean glass, but decomposed when the pressure went up to 30mm of mercury. However he believed that the formula was SO and called it sulfur monoxide. In 1940 K Kondrat'eva and V Kondrat'ev became convinced that the formula was S2O2, disulfur dioxide. However all were wrong until in 1956, David J. Meschi and Rollie J. Myers proved the formula was S2O.[7]

Natural occurrence

Desulfovibrio desulfuricans is claimed to produce S2O.[8] S2O can be found coming from volcanoes on Io. It can form from 1 to 6% when hot 100 bar S2 and SO2 gas erupts from volcanoes. It is believed that Pele on Io is surrounded by solid S2O.[9]

Reactions

A self decomposition can from trithio-ozone S3 and S2O. Also 5,6-di-tert-butyl-2,3,7-trithiabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene 2-endo-7-endo-dioxide when heated can form S2O.[10] It reacts with diazoalkanes for form dithiirane 1-oxides.[11]

Disulfur monoxide can be a ligand bound to transition metals. These are formed by oxidation with dioxygen for a disulfur ligand complex. Excessive oxygen can yield a dioxygendisulfur ligand, which can be reduced in turn with triphenylphosphine. Examples are: [Ir(dppe)2S2O]+, OsCl(NO)(PPh3)2S2O NbCl(η-C5H5)2S2O Mn(CO)2(η-C5Me5)S2O Re(CO)2(η-C5Me5)S2O Re(CO)2(η-C5H5)S2O.[12]

More complex nucleations occur with transition metal ligand combinations. With molybdenum Mo(CO)2(S2CNEt2)2 reacts with elemental sulfur and air to form a compound Mo2(S2O)2(S2CNEt2)4.[12] Another way to form these complexes is to combine iminooxosulfurane (OSNSO2.R) complexes with hydrogen sulfide.[12] Complexes formed in this way are: IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2S2O; Mn(CO)2(η-C5H5)S2O. With hydrosulfide and a base followed by oxygen, OsCl(NO)(PPh3)2S2O can be made.[12]

References

- ^ a b c d "Disulfur monoxide". NIST. 2008.

- ^ B Hapke and F Graham (May 1989). "Spectral properties of condensed phases of disulfur monoxide, polysulfur oxide, and irradiated sulfur". Icarus. 79 (1): 47. Bibcode:1989Icar...79...47H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90107-3.

- ^ Lauss, Hans-Dietrich; Steffens, Wilfried (2000). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_623. ISBN 3527306730.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Cotton and Wilkinson (1966). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry A Comprehensive Treatise. p. 540.

- ^ Meschi, D.J. (1959). "The microwave spectrum, structure, and dipole moment of disulfur monoxide". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 3 (1–6): 405–416. Bibcode:1959JMoSp...3..405M. doi:10.1016/0022-2852(59)90036-0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|quotes=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Alok Mittal (2002-01-01). Objective Chemistry For Iit Entrance. p. 13. ISBN 9788122413656.

- ^ David J. Meschi and Rollie J. Myers (30 July 1956). "Disulfur Monoxide. I. Its Identification as the Major Constituent in Schenk's "Sulfur Monoxide"". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (24): 6220. doi:10.1021/ja01605a002.

- ^ Iverson, WP (26 May 1967). "Disulfur monoxide: production by Desulfovibrio". Science. 156 (3778): 1112–4. Bibcode:1967Sci...156.1112I. doi:10.1126/science.156.3778.1112. PMID 6024190.

- ^ Mikhail Yu. Zolotov and Bruce Fegley (9 March 1998). "Volcanic Origin of Disulfur Monoxide (S2O) on Io" (PDF). Icarus. 133 (2): 293. Bibcode:1998Icar..133..293Z. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5930.

- ^ Nakayama J; Aoki, S; Takayama, J; Sakamoto, A; Sugihara, Y; Ishii, A (28 July 2004). "Reversible disulfur monoxide (S2O)-forming retro-Diels-Alder reaction. disproportionation of S2O to trithio-ozone (S3) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) and reactivities of S2O and S3". Journal of the American Chemical Societ. 126 (29): 9085. doi:10.1021/ja047729i. PMID 15264842.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ A Ishii; Kawai, T; Tekura, K; Oshida, H; Nakayama, J (18 May 2001). "A Convenient Method for the Generation of a Disulfur Monoxide Equivalent and Its Reaction with Diazoalkanes to Yield Dithiirane 1-Oxides". Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 40 (10): 1924–1926. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010518)40:10<1924::AID-ANIE1924>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 11385674.

- ^ a b c d F G A Stone (1994-03-07). Advances in Organometallic Chemistry, Volume 36. p. 168. ISBN 9780120311361.