Sulfonylurea

Sulfonylurea (UK: sulphonylurea) derivatives are a class of antidiabetic drugs that are used in the management of diabetes mellitus type 2. They act by increasing insulin release from the beta cells in the pancreas.

Drugs in this class

First generation

Second generation

- Glipizide

- Gliclazide

- Glibenclamide (glyburide)

- Glibornuride

- Gliquidone

- Glisoxepide

- Glyclopyramide

- Glimepiride

Some classify glimepiride as second-generation,[1] while others classify it as third-generation.[2]

Chemistry

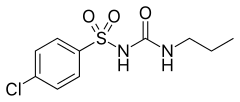

All sulfonylureas contain a central S-phenylsulfonylurea structure (red) with a p- substituent on the phenyl ring (R) and various groups terminating the urea N′ end group (R2).

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Sulfonylureas bind to an ATP-dependent K+(KATP) channel on the cell membrane of pancreatic beta cells. This inhibits a tonic, hyperpolarizing efflux of potassium, thus causing the electric potential over the membrane to become more positive. This depolarization opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The rise in intracellular calcium leads to increased fusion of insulin granulae with the cell membrane, and therefore increased secretion of (pro)insulin.

There is some evidence that sulfonylureas also sensitize β-cells to glucose, that they limit glucose production in the liver, that they decrease lipolysis (breakdown and release of fatty acids by adipose tissue) and decrease clearance of insulin by the liver.

The KATP channel is an octameric complex of the inward-rectifier potassium ion channel Kir6.2 and sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 which associate with a stoichiometry of Kir6.24/SUR14.

Pharmacokinetics

Various sulfonylureas have different pharmacokinetics. The choice depends on the propensity of the patient to develop hypoglycemia – long-acting sulfonylureas with active metabolites can induce hypoglycemia. They can, however, help achieve glycemic control when tolerated by the patient. The shorter-acting agents may not control blood sugar levels adequately.

Due to varying half-life, some drugs have to be taken twice (e.g. tolbutamide) or three times a day rather than once (e.g. glimepiride). The short-acting agents may have to be taken about 30 minutes before the meal, to ascertain maximum efficacy when the food leads to increased blood glucose levels.

Some sulfonylureas are metabolised by liver metabolic enzymes (cytochrome P450) and inducers of this enzyme system (such as the antibiotic rifampicin) can therefore increase the clearance of sulfonylureas. In addition, because some sulfonylureas are bound to plasma proteins, use of drugs that also bind to plasma proteins can release the sulfonylureas from their binding places, leading to increased clearance.

Uses

Sulfonylureas are used primarily for the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2. Sulfonylureas are ineffective where there is absolute deficiency of insulin production such as in type 1 diabetes or post-pancreatectomy.

Sulfonylureas can be used to treat neonatal diabetes. While historically patients with hyperglycemia and low blood insulin levels were diagnosed with Type I Diabetes by default, it has been found that patients who receive this diagnosis before 6 months of age are often, in fact, candidates for receiving sulfonylureas rather than insulin throughout life. [3]

Although for many years sulfonylureas were the first drugs to be used in new cases of diabetes, in the 1990s it was discovered that obese patients might benefit more from metformin.

In about 10% of patients, sulfonylureas alone are ineffective in controlling blood glucose levels. Addition of metformin or a thiazolidinedione may be necessary, or (ultimately) insulin. Triple therapy of sulfonylureas, a biguanide (metformin) and a thiazolidinedione is generally discouraged, but some doctors prefer this combination over resorting to insulin.

More recently, a pharmaceutical startup, Remedy Pharmaceuticals, Inc. has begun developing intravenous glyburide[4] as a treatment for acute stroke, traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury based on the identification of a non-selective ATP-gated cation channel which is upregulated in neurovascular tissue during these conditions and closed by sulfonylurea agents.[5][6]

Some diabetes experts feel that sulfonylureas accelerate the loss of beta cells from the pancreas, and should be avoided.[citation needed]

Side effects and cautions

Sulfonylureas, as opposed to metformin, the thiazolidinediones, exenatide, symlin and other newer treatment agents may induce hypoglycemia as a result of excesses in insulin production and release. This typically occurs if the dose is too high, and the patient is fasting. Some people attempt to change eating habits to prevent this, however it can be counter productive.

Like insulin, sulfonylureas can induce weight gain, mainly as a result their effect to increase insulin levels and thus utilization of glucose and other metabolic fuels. Other side-effects are: abdominal upset, headache and hypersensitivity reactions.

Sulfonylureas are potentially teratogenic and cannot be used in pregnancy or in patients who may become pregnant. Impairment of liver or kidney function increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and are contraindications. As other anti-diabetic drugs cannot be used either under these circumstances, insulin therapy is typically recommended during pregnancy and in hepatic and renal failure, although some of the newer agents offer potentially better options.

Second-generation sulfonylureas have increased potency by weight, compared to first-generation sulfonylureas. All sulfonylureas carry an FDA-required warning about increased risk of cardiovascular death. The ADVANCE trial (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease), a randomized trial sponsored by the vendor of gliclazide, found no benefit from tight control with gliclazide for the outcomes of heart attack (myocardial infarction), cardiovascular death, or all-cause death.[7] Similarly, ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes)[8] and the VADT (Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial)[9] studies showed no reduction in heart attack or death in patients assigned to tight glucose control with various drugs.

Interactions

Drugs that potentiate or prolong the effects of sulfonylureas and therefore increase the risk of hypoglycemia include acetylsalicylic acid and derivatives, allopurinol, sulfonamides, and fibrates. Drugs that worsen glucose tolerance, contravening the effects of antidiabetics, include corticosteroids, isoniazide, oral contraceptives and other estrogens, sympathomimetics, and thyroid hormones. Sulfonylureas tend to interact with a wide variety of other drugs, but these interactions, as well as their clinical significance, vary from substance to substance.[10][11]

History

Sulfonylureas were discovered by the chemist Marcel Janbon and co-workers,[12] who were studying sulfonamide antibiotics and discovered that the compound sulfonylurea induced hypoglycemia in animals.[13]

See also

References

- ^ Triplitt CL, Reasner CA (2011). "Chapter 83: diabetes mellitus". In DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM (ed.). Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 1274. ISBN 0-07-170354-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Davidson J (2000). Clinical diabetes mellitus: a problem-oriented approach. Stuttgart: Thieme. p. 422. ISBN 0-86577-840-X.

- ^ Greeley, Siri (2010). "Neonatal diabetes mellitus: A model for personalized medicine". Trends Endocrinol Metabolism. 21 (8): 464–472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Breakthrough Discovery Offers Hope to Stroke Victims". Carrot Capital. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Kunte H, Schmidt S, Eliasziw M, del Zoppo GJ, Simard JM, Masuhr F, Weih M, Dirnagl U (2007). "Sulfonylureas Improve Outcome in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Acute Ischemic Stroke". Stroke. 38 (9): 2526–30. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482216. PMC 2742413. PMID 17673715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simard JM, Woo SK, Bhatta S, Gerzanich V (2007). "Drugs acting on SUR1 to treat CNS ischemia and trauma". Curr Opin Pharmacol. 8 (1): 42–9. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.004. PMC 2265539. PMID 18032110.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Liu L, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan C, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Bompoint S, de Galan BE, Joshi R, Travert F (2008). "Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (24): 2560–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. PMID 18539916.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT (2008). "Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (24): 2545–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. PMID 18539917.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, Zieve FJ, Marks J, Davis SN, Hayward R, Warren SR, Goldman S, McCarren M, Vitek ME, Henderson WG, Huang GD (2009). "Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (2): 129–39. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. PMID 19092145.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haberfeld, H, ed. (2009). Austria-Codex (in German) (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 3-85200-196-X.

- ^ Dinnendahl, V.; Fricke, U., eds. (2010). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 4 (23 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Janbon M, Chaptal J, Vedel A, Schaap J (1942). "Accidents hypoglycémiques graves par un sulfamidothiodiazol (le VK 57 ou 2254 RP)". Montpellier Med. 441: 21–22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patlak M (2002). "New weapons to combat an ancient disease: treating diabetes". FASEB J. 16 (14): 1853. PMID 12468446.