Greece

Hellenic Republic Ελληνική Δημοκρατία Elliniki Dimokratia | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Eleftheria i thanatos, (Greek: "Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος", "Freedom or Death") (traditional) | |

| Anthem: "Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν" Ýmnos is tin Eleftherían "Hymn to Liberty"1 | |

![Location of Greece (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/EU-Greece.svg/250px-EU-Greece.svg.png) Location of Greece (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Athens |

| Official languages | Greek |

| Ethnic groups | 94% Greek, 4% Albanian, 2% others[1][2][3][4][5] |

| Demonym(s) | Greek (Officially: Hellenic) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Karolos Papoulias | |

| Antonis Samaras | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence from the Ottoman Empire | |

• Declared | 1 January 1822, at the First National Assembly |

• Recognized | 3 February 1830, in the London Protocol |

| 11 June 1975, Third Hellenic Republic | |

| Area | |

• Total | 131,990 km2 (50,960 sq mi) (96th) |

• Water (%) | 0.8669 |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 11,305,118[6] (74th) |

• 2011 (preliminary data) census | 10,787,690[7] |

• Density | 85.3/km2 (220.9/sq mi) (88th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $294.339 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $26,293[8] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $303.065 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $27,073[8] |

| Gini (2005) | 33[9] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2011) | Error: Invalid HDI value (29th) |

| Currency | Euro (€)2 (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 30 |

| ISO 3166 code | GR |

| Internet TLD | .gr3 |

| |

Greece /ˈɡriːs/ (Template:Lang-el, Ellada, IPA: [eˈlaða] historically in Katharevousa and Template:Lang-grc, Hellas, IPA: [eˈlas] and IPA: [helːás] respectively), officially the Hellenic Republic (Ελληνική Δημοκρατία, Elliniki Dimokratia, IPA: [eliniˈci ðimokraˈtia][10]), is a country in Southern Europe,[11] politically considered part of Western Europe.[12] Athens is the capital and the largest city in the country (its urban area also including Piraeus). The population of the country is about 11 million.

Greece has land borders with Albania, the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to the east. The Aegean Sea lies to the east of mainland Greece, the Ionian Sea to the west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. Greece has the 11th longest coastline in the world at 13,676 km (8,498 mi) in length, featuring a vast number of islands (approximately 1,400, of which 227 are inhabited), including Crete, the Dodecanese, the Cyclades, and the Ionian Islands among others. Eighty percent of Greece consists of mountains, of which Mount Olympus is the highest at 2,917 m (9,570 ft).

Modern Greece traces its roots to the civilization of ancient Greece, generally considered the cradle of Western civilization. As such it is the birthplace of democracy,[13] Western philosophy,[14] the Olympic Games, Western literature and historiography, political science, major scientific and mathematical principles, and Western drama,[15] including both tragedy and comedy. This legacy is partly reflected in the seventeen UNESCO World Heritage Sites located in Greece, ranking Greece 7th in Europe and 13th in the world. The modern Greek state was established in 1830, following the Greek War of Independence.

Greece has been a member of what is now the European Union since 1981 and the eurozone since 2001,[16] NATO since 1952,[17] and is a founding member of the United Nations. Greece is a developed country with an advanced,[18][19] high-income economy[20] and very high standards of living (including the 21st highest quality of life as of 2010).[21][22][23] Since late 2009, the Greek economy has been hit by a severe economic and financial crisis resulting in the Greek government requesting €240 billion in loans from EU institutions, a substantial debt write-off, and unpopular austerity measures.[24]

Name

Greece's name differs in comparison with the names used for the country in other languages and cultures, just like the names of the Greeks. Although the Greeks call the country Hellas or Ellada (Template:Lang-el) and its official name is Hellenic Republic, in English the country is called Greece, which comes from Latin Graecia as used by the Romans and literally means 'the land of the Greeks', and derives from the Greek name Γραικός; however, the name Hellas is sometimes used in English too.

History

From the earliest settlements to the 3rd century B.C.

The earliest evidence of human presence in the Balkans, dated to 270,000 BC, is to be found in the Petralona cave, in the northern Greek province of Macedonia.[25] Neolithic settlements in Greece, dating from the 7th millennium BC,[25] are the oldest in Europe by several centuries, as Greece lies on the route via which farming spread from the Near East to Europe.[26]

Greece is home to the first advanced civilizations in Europe, beginning with the Cycladic civilization on the islands of the Aegean Sea at around 3200 BC,[27] the Minoan civilization in Crete (2700–1500 BC) and then the Mycenaean civilization on the mainland (1900–1100 BC). These civilizations possessed writing, the Minoans writing in an undeciphered script known as Linear A, and the Myceneans in Linear B, an early form of Greek. The Myceneans gradually absorbed the Minoans, but collapsed violently around 1200 BC, during a time of regional upheaval known as the Bronze Age collapse.[28] This ushered in a period known as the Greek Dark Ages, from which written records are absent.

The end of the Dark Ages is traditionally dated to 776 BC, the year of the first Olympic Games.[29] The Iliad and the Odyssey, the foundational texts of Western literature, are believed to have been composed by Homer in the 8th or 7th centuries BC. With the end of the Dark Ages, there emerged various kingdoms and city-states across the Greek peninsula, which spread to the shores of the Black Sea, South Italy (known in Latin as Magna Graecia, or Greater Greece) and Asia Minor. These states and their colonies reached great levels of prosperity that resulted in an unprecedented cultural boom, that of classical Greece, expressed in architecture, drama, science, mathematics and philosophy. In 508 BC, Cleisthenes instituted the world's first democratic system of government in Athens.[30][31]

By 500 BC, the Persian Empire controlled territories ranging from what is now northern Greece and Turkey all the way to Iraq, and posed a threat to the Greek states. Attempts by the Greek city-states of Asia Minor to overthrow Persian rule failed, and Persia invaded the states of mainland Greece in 492 BC, but was forced to withdraw after a defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. A second invasion followed in 480 BC. Despite a heroic resistance at Thermopylae by Spartans and other Greeks, Persian forces sacked Athens. Following successive Greek victories in 480 and 479 BC at Salamis, Plataea and Mycale, the Persians were forced to withdraw for a second time. The military conflicts, known as the Greco-Persian Wars, were led mostly by Athens and Sparta. However, the fact that Greece was not a unified country meant that conflict between the Greek states was common. The most devastating of intra-Greek wars in classical antiquity was the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), which marked the demise of the Athenian Empire as the leading power in ancient Greece. Both Athens and Sparta were later overshadowed by Thebes and eventually Macedon, with the latter uniting the Greek world in the League of Corinth (also known as the Hellenic League or Greek League) under the guidance of Phillip II, who was elected leader of the first unified Greek state in the history of Greece.

Following the assassination of Phillip II, his son Alexander III ("The Great") assumed the leadership of the League of Corinth and launched an invasion of the Persian Empire with the combined forces of all Greek states in 334 BC. Following Greek victories in the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, the Greeks marched on Susa and Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of Persia, in 330 BC. The Empire created by Alexander the Great stretched from Greece in the west and Pakistan in the east, and Egypt in the south. Before his sudden death in 323 BC, Alexander was also planning an invasion of Arabia. His death marked the collapse of the vast empire, which was split into several kingdoms, the most famous of which were the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Egypt. Other states founded by Greeks include the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the Greco-Indian Kingdom in India. Although the political unity of Alexander's empire could not be maintained, it brought about the dominance of Hellenistic civilization and the Greek language in the territories conquered by Alexander for at least two centuries, and, in the case of parts the Eastern Mediterranean, considerably longer.[32]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

After a period of confusion following Alexander's death, the Antigonid dynasty, descended from one of Alexander's generals, established its control over Macedon by 276 B.C., as well as hegemony over most of the Greek city-states.[33] From about 200 B.C the Roman Republic became increasingly involved in Greek affairs and engaged in a series of wars with Macedon.[34] Macedon's defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 signaled the end of Antigonid power in Greece.[35] In 146 B.C. Macedonia was annexed as a province by Rome, and the rest of Greece became a Roman protectorate.[34][36] The process was completed in 27 B.C. when the Roman Emperor Augustus annexed the rest of Greece and constituted it as the senatorial province of Achaea.[36] Despite their military superiority, the Romans admired and became heavily influenced by the achievements of Greek culture, hence Horace's famous statement: Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit ("Greece, although captured, took its wild conqueror captive").[37]

Greek-speaking communities of the Hellenized East were instrumental in the spread of early Christianity in the 2nd and 3rd centuries,[38] and Christianity's early leaders and writers (notably St Paul) were generally Greek-speaking,[39] though none were from Greece. However, Greece itself had a tendency to cling on to paganism and was not one of the influential centers of early Christianity: in fact, some ancient Greek religious practices remained in vogue until the end of the 4th century,[40] with some areas such as the southeastern Peloponnese remaining pagan until well into the 10th century AD.[41]

Medieval period

The Roman Empire in the east, following the fall of the Empire in the west in the 5th century, is known to history as the Byzantine Empire and lasted until 1453. With its capital in Constantinople, its language and literary culture was Greek and its religion was predominantly Eastern Orthodox.[42] From the 4th century, the Empire's Balkan territories, including Greece, suffered from the dislocation of the Barbarian Invasions. The raids and devastation of the Goths and Huns in the 4th and 5th centuries and the Slavic invasion of Greece in the 7th century resulted in a dramatic collapse in imperial authority in the Greek peninsula.[43] Following the Slavic invasion, the imperial government retained control of only the islands and coastal areas, particularly cities such as Athens, Corinth and Thessalonica, while some mountainous areas in the interior held out on their own and continued to recognize imperial authority.[43] Outside of these areas, a limited amount of Slavic settlement is generally thought to have occurred, although on a much smaller scale than previously thought.[44][45]

The Byzantine recovery of lost provinces began toward the end of the 8th century and most of the Greek peninsula came under imperial control again, in stages, during the 9th century.[46][47] This process was facilitated by a large influx of Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor to the Greek peninsula, while at the same time many Slavs were captured and re-settled in Asia Minor and those that remained were assimilated.[44] During the 11th and 12th centuries the return of stability resulted in the Greek peninsula benefiting from strong economic growth – much stronger than that of the Anatolian territories of the Empire.[46] Following the Fourth Crusade and the fall of Constantinople to the “Latins” in 1204 most of Greece quickly came under Frankish rule [48] (initiating the period known as the Frankokratia) or Venetian rule in the case of some of the islands.[49] The re-establishment of the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople in 1261 was accompanied by the recovery of much of the Greek peninsula, although the Frankish Principality of Achaea in the Peloponnese remained an important regional power into the 14th century.[48]

In the 14th century much of the Greek peninsula was lost by the Empire as first the Serbs and then the Ottomans seized imperial territory.[50] By the beginning of the 15th century, the Ottoman advance meant that Byzantine territory in Greece was limited mainly to the Despotate of the Morea in the Peloponnese.[50] After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, the Morea was the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire to hold out against the Ottomans. However, this, too, fell to the Ottomans in 1460, completing the Ottoman conquest of mainland Greece.[51] With the Turkish conquest, many Byzantine Greek scholars, who up until then were largely responsible for preserving Classical Greek knowledge, fled to the West, taking with them a large body of literature and thereby significantly contributing to the Renaissance.[52]

Ottoman period

While most of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands were under Ottoman control by the end of the 15th century, Cyprus and Crete remained Venetian territory and did not fall to the Ottomans until 1571 and 1670, respectively. The only part of the Greek-speaking world that escaped long-term Ottoman rule were the Ionian Islands, which remained Venetian until their capture by the First French Republic in 1797, then passed to the United Kingdom in 1809 until their unification with Greece in 1864.[53]

While Greeks in the Ionian Islands and Constantinople lived in prosperity, the latter achieving positions of power within the Ottoman administration,[53] much of the population of mainland Greece suffered the economic consequences of the Ottoman conquest. Heavy taxes were enforced, and in later years the Ottoman Empire enacted a policy of creation of hereditary estates, effectively turning the rural Greek populations into serfs.[54]

The Greek Orthodox Church and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople were considered by the Ottoman governments as the ruling authorities of the entire Orthodox Christian population of the Ottoman Empire, whether ethnically Greek or not. Although the Ottoman state did not force non-Muslims to convert to Islam, Christians faced several types of discrimination intended to highlight their inferior status in the Ottoman Empire. Discrimination against Christians, particularly when combined with harsh treatment by local Ottoman authorities, led to conversions to Islam, if only superficially. In the nineteenth century, many "crypto-Christians" returned to their old religious allegiance.[53]

The nature of Ottoman administration of Greece varied, though it was invariably arbitrary and often harsh.[53] Some cities had governors appointed by the Sultan, while others, (like Athens), were self-governed municipalities. Mountains regions in the interior and many islands remained effectively autonomous from the central Ottoman state for many centuries.[53]

When military conflicts broke out between the Ottoman Empire and other states, Greeks usually took arms against the Empire, with few exceptions. Prior to the Greek revolution, there had been a number of wars which saw Greeks fight against the Ottomans, such as the Greek participation in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Epirus peasants' revolts of 1600–1601, the Morean War of 1684–1699 and the Russian-instigated Orlov Revolt in 1770 which aimed at breaking up the Ottoman Empire in favor of Russian interests.[53] These uprisings were put down by the Ottomans with great bloodshed.[55][56]

The 16th and 17th centuries are regarded as something of a "dark age" in Greek history, with the prospect of overthrowing Ottoman rule appearing remote. However in the 18th century, there arose through shipping a wealthy and dispersed Greek merchant class. These merchants came to dominate trade within the Ottoman Empire, establishing communities throughout the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Western Europe. Though the Ottoman conquest had cut Greece off from significant European intellectual movements such as the Reformation and the Enlightenment, these ideas together with the ideals of the French Revolution and romantic nationalism began to penetrate the Greek world via the mercantile diaspora.[53] In the late 18th century, Rigas Feraios, the first revolutionary to envision an independent Greek state, published a series of documents relating to Greek independence, including but not limited to a national anthem and the first detailed map of Greece, in Vienna, but was murdered by Ottoman agents in 1798.[53][57]

The War of Independence

In 1814, a secret organization called the Filiki Eteria was founded with the aim of liberating Greece. The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolution in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities and Constantinople. The first of these revolts began on 6 March 1821 in the Danubian Principalities under the leadership of Alexandros Ypsilantis, but it was soon put down by the Ottomans. The events in the north urged the Greeks in the Peloponnese in action and on 17 March 1821 the Maniots declared war on the Ottomans. By the end of the month, the Peloponnese was in open revolt against the Ottomans and by October 1821 the Greeks under Theodoros Kolokotronis had captured Tripolitsa. The Peloponnesian revolt was quickly followed by revolts in Crete, Macedonia and Central Greece, which would soon be suppressed. Meanwhile, the makeshift Greek navy was achieving success against the Ottoman navy in the Aegean Sea and prevented Ottoman reinforcements from arriving by sea. However in 1823 the Turks and Egyptians ravaged the islands, including Chios and Psara, committing wholesale massacres of the population.[58] This had the effect of galvanizing public opinion in western Europe in favor of the Greek rebels.[53]

Tensions soon developed among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Sultan negotiated with Mehmet Ali of Egypt, who agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain. Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese in February 1825 and had immediate success: by the end of 1825, most of the Peloponnese was under Egyptian control, and the city of Missolonghi—put under siege by the Turks since April 1825—fell in April 1826. Although Ibrahim was defeated in Mani, he had succeeded in suppressing most of the revolt in the Peloponnese and Athens had been retaken.

Following years of negotiation, three Great Powers, Russia, the United Kingdom and France, decided to intervene in the conflict and each nation sent a navy to Greece. Following news that combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleets were going to attack the Greek island of Hydra, the allied fleet intercepted the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet at Navarino. Following a week long standoff, a battle began which resulted in the destruction of the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet. With the help of a French expeditionary force, the Greeks drove the Turks out of the Peloponnese and proceeded to the captured part of Central Greece by 1828. As a result of years of negotiation, the nascent Greek state was finally recognized under the London Protocol in 1830.

The 19th century

In 1827 Ioannis Kapodistrias, from Corfu, was chosen as the first governor of the new Republic. However, following his assassination in 1831, the Great Powers installed a monarchy under Otto, of the Bavarian House of Wittelsbach. In 1843 an uprising forced the king to grant a constitution and a representative assembly.

Due to his unimpaired authoritarian rule he was eventually dethroned in 1862 and a year later replaced by Prince Wilhelm (William) of Denmark, who took the name George I and brought with him the Ionian Islands as a coronation gift from Britain. In 1877 Charilaos Trikoupis, who is credited with significant improvement of the country's infrastructure, curbed the power of the monarchy to interfere in the assembly by issuing the rule of vote of confidence to any potential prime minister.

Corruption and Trikoupis' increased spending to create necessary infrastructure like the Corinth Canal overtaxed the weak Greek economy, forcing the declaration of public insolvency in 1893 and to accept the imposition of an International Financial Control authority to pay off the country's debtors. Another political issue in 19th-century Greece was uniquely Greek: the language question. The Greek people spoke a form of Greek called Demotic. Many of the educated elite saw this as a peasant dialect and were determined to restore the glories of Ancient Greek. Government documents and newspapers were consequently published in Katharevousa (purified) Greek, a form which few ordinary Greeks could read. Liberals favoured recognising Demotic as the national language, but conservatives and the Orthodox Church resisted all such efforts, to the extent that, when the New Testament was translated into Demotic in 1901, riots erupted in Athens and the government fell (the Evangeliaka). This issue would continue to plague Greek politics until the 1970s.

All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Especially in Crete, a prolonged revolt in 1866–1869 had raised nationalist fervour. When war broke out between Russia and the Ottomans in 1877, Greek popular sentiment rallied to Russia's side, but Greece was too poor, and too concerned of British intervention, to officially enter the war. Nevertheless, in 1881, Thessaly and small parts of Epirus were ceded to Greece as part of the Treaty of Berlin, while frustrating Greek hopes of receiving Crete. Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897, the Greek government under Theodoros Deligiannis, bowing to popular pressure, declared war on the Ottomans. In the ensuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897 the badly trained and equipped Greek army was defeated by the Ottomans. Through the intervention of the Great Powers however, Greece lost only a little territory along the border to Turkey, while Crete was established as an autonomous state under Prince George of Greece.

The 20th century and beyond

As a result of the Balkan Wars Greece increased the extent of its territory and population. In the following years, the struggle between King Constantine I and charismatic Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos over the country's foreign policy on the eve of World War I dominated the country's political scene, and divided the country into two opposing groups. During part of WWI, Greece had two governments; a royalist pro-German government in Athens and a Venizelist pro-Britain one in Thessaloniki. The two governments were united in 1917, when Greece officially entered the war on the side of the Triple Entente.

In the aftermath of The First World War Greece fought against Turkish nationalists led by Mustafa Kemal, a war which resulted in a massive population exchange between the two countries under the Treaty of Lausanne.[59] According to various sources,[60] several hundred thousand Pontic Greeks died during this period.[61] Instability and successive coups d'état marked the following era, which was overshadowed by the massive task of incorporating 1.5 million Greek refugees from Turkey into Greek society. The Greek population in Istanbul dropped from 300,000 at the turn of the 20th century to around 3,000 in the city today.[62]

Following the catastrophic events in Asia Minor, the monarchy was abolished via a referendum in 1924 and the Second Hellenic Republic was declared. Premier Georgios Kondylis took power in 1935 and effectively abolished the republic by bringing back the monarchy via a referendum in 1935. A coup d'état followed in 1936 and installed Ioannis Metaxas as the head of a fascist regime known as the 4th of August Regime. Although fascist, Greece remained in good terms with Britain and was not allied with the Axis.

On 28 October 1940 Fascist Italy demanded the surrender of Greece, but Greek dictator Metaxas refused and in the following Greco-Italian War, Greece repelled Italian forces into Albania, giving the Allies their first victory over Axis forces on land. The country would eventually fall to urgently dispatched German forces during the Battle of Greece. The German occupiers nevertheless met serious challenges from the Greek Resistance. Over 100,000 civilians died from starvation during the winter of 1941–42, and the great majority of Greek Jews were deported to Nazi extermination camps.[63]

After liberation, Greece experienced a bitter civil war between communist and anticommunist forces, which led to economic devastation and severe social tensions between rightists and largely communist leftists for the next thirty years.[64] The next twenty years were characterized by marginalisation of the left in the political and social spheres but also by rapid economic growth, propelled in part by the Marshall Plan.

King Constantine II's dismissal of George Papandreou's centrist government in July 1965 prompted a prolonged period of political turbulence which culminated in a coup d'état on 21 April 1967 by the United States-backed Regime of the Colonels. The brutal suppression of the Athens Polytechnic uprising on 17 November 1973 sent shockwaves through the regime, and a counter-coup established Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannidis as dictator. On 20 July 1974, as Turkey invaded the island of Cyprus, the regime collapsed.

Former prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis was invited back from Paris where he had lived in self-exile since 1963, marking the beginning of the Metapolitefsi era. On 14 August 1974 Greek forces withdrew from the integrated military structure of NATO in protest at the Turkish occupation of northern Cyprus.[65][66] The first multiparty elections since 1964 were held on the first anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising. A democratic and republican constitution was promulgated on 11 June 1975 following a referendum which chose to not restore the monarchy.

Meanwhile, Andreas Papandreou founded the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) in response to Karamanlis's conservative New Democracy party, with the two political formations alternating in government ever since. Greece rejoined NATO in 1980.[65] Traditionally strained relations with neighbouring Turkey improved when successive earthquakes hit both nations in 1999, leading to the lifting of the Greek veto against Turkey's bid for EU membership.

Greece became the tenth member of the European Communities (subsequently subsumed by the European Union) on 1 January 1981, ushering in a period of remarkable and sustained economic growth. Widespread investments in industrial enterprises and heavy infrastructure, as well as funds from the European Union and growing revenues from tourism, shipping and a fast-growing service sector have raised the country's standard of living to unprecedented levels. The country adopted the euro in 2001 and successfully hosted the 2004 Summer Olympic Games in Athens.

More recently, Greece has been hit hard by the late-2000s recession and central to the related European sovereign debt crisis. The Greek government debt crisis, subsequent economic crisis and resultant, sometimes violent protests have roiled domestic politics and have regularly threatened both European and world financial market stability in since the crisis began in 2010.

Geography and climate

Greece consists of a mountainous, peninsular mainland jutting out into the sea at the southern end of the Balkans, ending at the Peloponnese peninsula (separated from the mainland by the canal of the Isthmus of Corinth). Due to its highly indented coastline and numerous islands, Greece has the 11th longest coastline in the world with13,676 km (8,498 mi);[67] its land boundary is 1,160 km (721 mi). The country lies approximately between latitudes 34° and 42° N, and longitudes 19° and 30° E.

Greece features a vast number of islands, between 1,200 and 6,000, depending on the definition,[68] 227 of which are inhabited. Crete is the largest and most populous island; Euboea, separated from the mainland by the 60m-wide Euripus Strait, is the second largest, followed by Rhodes and Lesbos.

The Greek islands are traditionally grouped into the following clusters: The Argo-Saronic Islands in the Saronic gulf near Athens, the Cyclades, a large but dense collection occupying the central part of the Aegean Sea, the North Aegean islands, a loose grouping off the west coast of Turkey, the Dodecanese, another loose collection in the southeast between Crete and Turkey, the Sporades, a small tight group off the coast of Euboea, and the Ionian Islands, located to the west of the mainland in the Ionian Sea.

Eighty percent of Greece consists of mountains or hills, making the country one of the most mountainous in Europe. Mount Olympus, the mythical abode of the Greek Gods, culminates at Mytikas peak 2,917 m (9,570 ft), the highest in the country. Western Greece contains a number of lakes and wetlands and is dominated by the Pindus mountain range. The Pindus, a continuation of the Dinaric Alps, reaches a maximum elevation of 2,637 m (8,652 ft) at Mt. Smolikas (the second-highest in Greece) and historically has been a significant barrier to east-west travel.

The Pindus range continues through the central Peloponnese, crosses the islands of Kythera and Antikythera and find its way into southwestern Aegean, in the island of Crete where it eventually ends. The islands of the Aegean are peaks of underwater mountains that once constituted an extension of the mainland. Pindus is characterized by its high, steep peaks, often dissected by numerous canyons and a variety of other karstic landscapes. The spectacular Vikos Gorge, part of the Vikos-Aoos National Park in the Pindus range, is listed by the Guinness book of World Records as the deepest gorge in the world.[69] Another notable formation are the Meteora rock pillars, atop which have been built medieval Greek Orthodox monasteries.

Northeastern Greece features another high-altitude mountain range, the Rhodope range, spreading across the region of East Macedonia and Thrace; this area is covered with vast, thick, ancient forests, including the famous Dadia forest in the Evros regional unit, in the far northeast of the country.

Extensive plains are primarily located in the regions of Thessaly, Central Macedonia and Thrace. They constitute key economic regions as they are among the few arable places in the country. Rare marine species such as the Pinniped Seals and the Loggerhead Sea Turtle live in the seas surrounding mainland Greece, while its dense forests are home to the endangered brown bear, the lynx, the Roe Deer and the Wild Goat.

The climate of Greece is primarily Mediterranean, featuring mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. This climate occurs at all coastal locations, including Athens, the Cyclades, the Dodecanese, Crete, the Peloponnese and parts of the Sterea Ellada (Central Continental Grece) region. The Pindus mountain range strongly affects the climate of the country, as areas to the west of the range are considerably wetter on average (due to greater exposure to south-westerly systems bringing in moisture) than the areas lying to the east of the range (due to a rain shadow effect).

The mountainous areas of Northwestern Greece (parts of Epirus, Central Greece, Thessaly, Western Macedonia) as well as in the mountainous central parts of Peloponnese – including parts of the regional units of Achaea, Arcadia and Laconia – feature an Alpine climate with heavy snowfalls. The inland parts of northern Greece, in Central Macedonia and East Macedonia and Thrace feature a temperate climate with cold, damp winters and hot, dry summers with frequent thunderstorms. Snowfalls occur every year in the mountains and northern areas, and brief snowfalls are not unknown even in low-lying southern areas, such as Athens.

Phytogeographically, Greece belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is shared between the East Mediterranean province of the Mediterranean Region and the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature and the European Environment Agency, the territory of Greece can be subdivided into six ecoregions: the Illyrian deciduous forests, Pindus Mountains mixed forests, Balkan mixed forests, Rhodope montane mixed forests, Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests and Crete Mediterranean forests.

Politics

Greece is a parliamentary republic.[70] The nominal head of state is the President of the Republic, who is elected by the Parliament for a five-year term.[70] The current Constitution was drawn up and adopted by the Fifth Revisionary Parliament of the Hellenes and entered into force in 1975 after the fall of the military junta of 1967–1974. It has been revised three times since, in 1986, 2001 and in 2008. The Constitution, which consists of 120 articles, provides for a separation of powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and grants extensive specific guarantees (further reinforced in 2001) of civil liberties and social rights.[71] Women's suffrage was guaranteed with a 1952 Constitutional amendment.

According to the Constitution, executive power is exercised by the President of the Republic and the Government.[70] From the Constitutional amendment of 1986 the President's duties were curtailed to a significant extent, and they are now largely ceremonial; most political power thus lies in the hands of the Prime Minister.[72] The position of Prime Minister, Greece's head of government, belongs to the current leader of the political party that can obtain a vote of confidence by the Parliament. The President of the Republic formally appoints the Prime Minister and, on his recommendation, appoints and dismisses the other members of the Cabinet.[70]

Legislative powers are exercised by a 300-member elective unicameral Parliament.[70] Statutes passed by the Parliament are promulgated by the President of the Republic.[70] Parliamentary elections are held every four years, but the President of the Republic is obliged to dissolve the Parliament earlier on the proposal of the Cabinet, in view of dealing with a national issue of exceptional importance.[70] The President is also obliged to dissolve the Parliament earlier, if the opposition manages to pass a motion of no confidence.[70]

The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature and comprises three Supreme Courts: the Court of Cassation (Άρειος Πάγος), the Council of State (Συμβούλιο της Επικρατείας) and the Court of Auditors (Ελεγκτικό Συνέδριο). The Judiciary system is also composed of civil courts, which judge civil and penal cases and administrative courts, which judge disputes between the citizens and the Greek administrative authorities.

Political parties

Since the restoration of democracy, the Greek two-party system is dominated by the liberal-conservative New Democracy (ND) and the social-democratic Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK).[73] Other significant parties include the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) and the Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS). In 2010, two new parties split off from ND and SYRIZA, the centrist-liberal Democratic Alliance (DS) and the moderate leftist Democratic Left (DA). George Papandreou, president of PASOK, won 4 October 2009, won with a majority in the Parliament of 160 out of 300 seats. A new government was sworn in on 20 June 2011, and received a marginal vote of confidence on 22 June, with 155 votes for, 143 against, and two MPs absent.[74] Since the beginning in 2010 of the government-debt crisis, the two major parties, New Democracy and PASOK, have seen a sharp decline in the share of votes in polls conducted, with recent polls showing support from 34% to 48% for the two major parties.[75][76][77][78][79] Polls show support for PASOK ranging from 8%[79] to 18%,[75] while New Democracy is in the 18% to 30% range.[75][77]

In November 2011, the two major parties joined the smaller Popular Orthodox Rally in a grand coalition, pledging their parliamentary support for a government of national unity headed by former European Central Bank vice-president Lucas Papademos.[80]

Administrative divisions

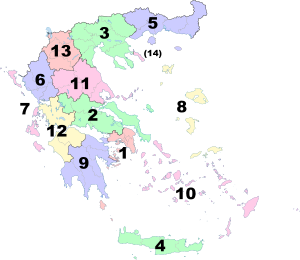

Since the Kallikratis programme reform entered into effect on 1 January 2011, Greece consists of thirteen regions subdivided into a total of 325 municipalities. The 54 old prefectures and prefecture-level administrations have been largely retained as sub-units of the regions. Seven decentralized administrations group one to three regions for administrative purposes on a regional basis. There is also one autonomous area, Mount Athos (Template:Lang-el, "Holy Mountain"), which borders the region of Central Macedonia.

|

|

Foreign relations

Greece's foreign policy is conducted through the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and its head, the Minister for Foreign Affairs. The current minister is Stavros Dimas of the New Democracy party. According to the official website, the main aims of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs are to represent Greece before other states and international organizations;[82] safeguarding the interests of the Greek state and of its citizens abroad;[82] the promotion of Greek culture;[82] the fostering of closer relations with the Greek diaspora;[82] and the promotion of international cooperation.[82] Additionally, Greece has developed a regional policy to help promote peace and stability in the Balkans, the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[83]

The Ministry identifies three issues as of particular importance to the Greek state: Turkish claims over what the Ministry defines as Greek sovereignty over the Aegean Sea and corresponding airspace;[84] the legitimacy of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus on the island of Cyprus;[84] and the Macedonia naming dispute[84] with the small Balkan country which shares a name with Greece's largest and second-most-populous region, also called Macedonia.

Greece is a member of numerous international organizations, including the Council of Europe, the European Union, the Union for the Mediterranean and the United Nations, of which it is a founding member.

Military

Hellenic Army Leopard 2A6 HEL |

Hellenic Navy MEKO-200 HN |

Hellenic Air Force Mirage 2000 |

The Hellenic Armed Forces are overseen by the Hellenic National Defense General Staff (Γενικό Επιτελείο Εθνικής Άμυνας – ΓΕΕΘΑ) and consists of three branches:

The civilian authority for the Greek military is the Ministry of National Defence. Furthermore, Greece maintains the Hellenic Coast Guard for law enforcement in the sea and for search and rescue.

Greece has universal compulsory military service for males, while females (who may serve in the military) are exempted from conscription. As of 2009[update], Greece has mandatory military service of nine months for male citizens between the ages of 19 and 45. However, as the armed forces had been gearing towards a complete professional army system, the government had promised that the mandatory military service would be cut or even abolished completely.

Greek males between the age of 18 and 60 who live in strategically sensitive areas may be required to serve part-time in the National Guard. Service in the Guard is paid. As a member of NATO, the Greek military participates in exercises and deployments under the auspices of the alliance.

Greece spends over 9 billion US Dollars every year on its military, or 3.2% of GDP, ranked 20th in the world. On a per capita level, Greece is ranked 8th.

Economy

Since 2010, the Greek economy has been hit by the most severe of the European sovereign debt crises. Greece's GDP (Gross Domestic Product) shrunk by 6.9% in 2011 and by 3.4% in 2010.[85] The country's public debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 165.3% of nominal gross domestic product in 2011.[86][87] The ongoing crisis has led to concerns of a run on the Greek banks, a forced exit from the Euro and, according to the Greek President, a "threat to our national existence".[88]

The pre-crisis economy

Prior to the crisis, GDP had expanded at an average annual rate of 4% from 2004–2007, one of the highest rates in the Eurozone.[89]

The tourism industry remains a major source of foreign exchange earnings and revenue and accounted for 15% of Greece's total GDP[90] and employing, directly or indirectly, 16.5% of the total workforce.

The Greek labour force totals 4.9 million, and it is the second-most-industrious among OECD countries, after South Korea.[91] The Groningen Growth & Development Centre published a poll revealing that between 1995 and 2005, Greece ranked third in the "working hours per year ranking" among European nations; Greeks worked an average of 1,811 hours per year.[92] In 2007, the average worker produced around 20 dollars per hour, similar to Spain and slightly more than half of average U.S. worker's hourly output. Immigrants made up nearly one-fifth of the work force, occupied in mainly agricultural and construction work.

Greece's purchasing power-adjusted GDP per capita was the world's 25th highest. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it had an estimated average per capita income of $29,882 for the year 2009, a figure slightly higher than that of Italy and Spain. According to Eurostat data, Greek PPS GDP per capita stood at 95 per cent of the EU average in 2009.[93] According to a survey by The Economist,[when?] the cost of living in Athens was close to 90% of the costs in New York City; in rural regions it is lower.[94]

In Greece, the euro was introduced in 2002. As a preparation for this date, the minting of the new euro coins started as early as 2001. However, all Greek euro coins introduced in 2002 have this year on it, unlike some other countries of the Eurozone where mint year is minted in the coin. Eight different designs, one per face value, were selected for the Greek coins. In 2007, in order to adopt the new common map like the rest of the Eurozone countries, Greece changed the common side of their coins. Before adopting the euro in 2002, Greece had maintained use of the Greek drachma from 1832.

In 2009, Greece had the EU's second-lowest Index of Economic Freedom (after Poland), ranking 81st in the world.[citation needed] The country suffers from high levels of political and economic corruption and low global competitiveness relative to its EU partners.[citation needed] The Greek economy faces significant problems, including rising unemployment levels and an inefficient government bureaucracy.[verification needed]

Although remaining above the euro area average, economic growth turned negative in 2009 for the first time since 1993.[95][verification needed] An indication of the trend of over-lending in recent years is the fact that the ratio of loans to savings exceeded 100% during the first half of the year.[96]

Debt crisis (2010–2012)

By the end of 2009, as a result of a combination of international and local factors (respectively, the world financial crisis and uncontrolled government spending), the Greek economy faced its most-severe crisis since the restoration of democracy in 1974 as the Greek government revised its deficit from an estimated 6% to 12.7% of gross domestic product (GDP).[97][98]

In early 2010, it was revealed that successive Greek governments had been found to have consistently and deliberately misreported the country's official economic statistics to keep within the monetary union guidelines.[99][100] This had enabled Greek governments to spend beyond their means, while hiding the actual deficit from the EU overseers.[101] In May 2010, the Greek government deficit was again revised and estimated to be 13.6%[102] which was one of the highest in the world relative to GDP[103] and public debt was forecast, according to some estimates, to hit 120% of GDP during 2010,[104] one of the highest rates in the world.

As a consequence, there was a crisis in international confidence in Greece's ability to repay its sovereign debt. In order to avert such a default, in May 2010 the other Eurozone countries, and the IMF, agreed to a rescue package which involved giving Greece an immediate €45 billion in loans, with more funds to follow, totaling €110 billion.[105][106] In order to secure the funding, Greece was required to adopt harsh austerity measures to bring its deficit under control.[107]

On 15 November 2010 the EU's statistics body Eurostat revised the public finance and debt figure for Greece following an excessive deficit procedure methodological mission in Athens, and put Greece's 2009 government deficit at 15.4% of GDP and public debt at 126.8% of GDP making it the biggest deficit (as a percentage of GDP) amongst the EU member nations (although some have speculated that Ireland's in 2010 may prove to be worse).[108][109][110][111]

In 2011 it became apparent that the bail-out would be insufficient and a second bail-out amounting to €130 billion ($173 billion) was agreed in 2012, subject to strict conditions, including financial reforms and further austerity measures.[24] As part of the deal, there was to be a 53% reduction in the Greek debt burden to private creditors and any profits made by eurozone central banks on their holdings of Greek debt are to be repatriated back to Greece.[24] A team of monitors will be based in Athens to ensure agreed reforms are put into place and three months worth of debt repayments are to be held in a special account.[24]

An inconclusive election on 6 May 2012 has resulted in a power struggle between parties willing to accept austerity measures, and those that reject them.[24] The political instability has led to fears of a run on Greek banks with almost €1 billion being withdrawn from Greek bank accounts in the week following the election.[88]

Maritime industry

The shipping industry is a key element of Greek economic activity dating back to ancient times.[112] Today, shipping is one of the country's most important industries. It accounts for 4.5% of GDP, employs about 160,000 people (4% of the workforce), and represents 1/3 of the country's trade deficit.[113]

During the 1960s, the size of the Greek fleet nearly doubled, primarily through the investment undertaken by the shipping magnates, Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos.[114] The basis of the modern Greek maritime industry was formed after World War II when Greek shipping businessmen were able to amass surplus ships sold to them by the U.S. government through the Ship Sales Act of the 1940s.[114]

According to a United Nations Conference on Trade and Development report in 2011, the Greek merchant navy is the largest in the world at 16.2% of the world's total capacity,[115] up from 15.96% in 2010.[116] This is a drop from the equivalent number in 2006, which was 18.2%.[117] The total tonnage of the country's merchant fleet is 202 million dwt, ranked 1st in the world.[115] In terms of total number of ships, the Greek Merchant Navy stands at 4th worldwide, with 3,150 ships (741 of which are registered in Greece whereas the rest 2,409 in other ports).[116] In terms of ship categories, Greece ranks first in both tankers and dry bulk carriers, fourth in the number of containers, and fourth in other ships.[118] However, today's fleet roster is smaller than an all-time high of 5,000 ships in the late 1970s.[112] Additionally, the total number of ships flying a Greek flag (includes non-Greek fleets) is 1,517, or 5.3% of the world's dwt (ranked 5th).[116]

Tourism

An important percentage of Greece's national income comes from tourism. According to Eurostat statistics, Greece welcomed over 19.5 million tourists in 2009,[119] which is an increase from the 17.7 million tourists it welcomed in 2007.[120] The vast majority of visitors in Greece in 2007 came from the European continent, numbering 12.7 million,[121] while the most visitors from a single nationality were those from the United Kingdom, (2.6 million), followed closely by those from Germany (2.3 million).[121] In 2010, the most visited region of Greece was that of Central Macedonia, with 18% of the country's total tourist flow (amounting to 3.6 million tourists), followed by Attica with 2.6 million and the Peloponnese with 1.8 million.[119] Northern Greece is the country's most-visited geographical region, with 6.5 million tourists, while Central Greece is second with 6.3 million.[119]

In 2010, Lonely Planet ranked Greece's northern and second-largest city of Thessaloniki as the world's fifth-best party town worldwide, comparable to other cities such as Dubai and Montreal.[122] In 2011, Santorini was voted as "The World's Best Island" in Travel + Leisure.[123] Its neighboring island Mykonos, came in fifth in the European category.[123]

Transport

Since the 1980s, the road and rail network of Greece has been significantly modernized. Important works include the A2 (Egnatia Odos) motorway, that connects northwestern Greece (Igoumenitsa) with northern and northeastern Greece (Kipoi); and the Rio–Antirrio bridge, the longest suspension cable bridge in Europe (2250 m or 7382 ft long), connecting the western Peloponnese from Rio (7 km or 4 mi from Patras) with Antirrio in Central Greece.

Important projects that are currently underway include, the conversion of the GR-8A, connecting Athens with Patras and further towards Pyrgos in the western Peloponnese, into a modernised motorway throughout its length (scheduled to be completed by 2014); upgrading unfinished sections of motorway on the A1, connecting Athens to Thessaloniki; and the construction of the Thessaloniki Metro.

The Athens Metropolitan Area in particular is served by some of the most modern and efficient transport infrastructure in Europe, such as the Athens International Airport, the privately run Attiki Odos motorway network and the expanded Athens Metro system.

Most of the Greek islands and many main cities of Greece are connected by air mainly from the two major Greek airlines, Olympic Air and Aegean Airlines. Maritime connections have been improved with modern high-speed craft, including hydrofoils and catamarans.

Railway connections play a somewhat lesser role in Greece than in many other European countries, but they too have also been expanded, with new suburban/commuter rail connections, serviced by Proastiakos around Athens, towards its airport, Kiato and Chalkida; around Thessaloniki, towards the cities of Larissa and Edessa; and around Patras. A modern intercity rail connection between Athens and Thessaloniki has also been established, while an upgrade to double lines in many parts of the 2,500 km (1,600 mi) network is underway. International railway lines connect Greek cities with the rest of Europe, the Balkans and Turkey, although as of 2011[update] they have been suspended, due to the financial crisis.

Telecommunications

Broadband internet availability is widespread in Greece: there were a total of 2,252,653 broadband connections as of early 2011[update], translating to 20% broadband penetration[124]. According to 2011 EU data, 47% of the population used the internet regularly.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Internet cafés that provide net access, office applications and multiplayer gaming are also a common sight in the country, while mobile internet on 3G cellphone networks and Wi-Fi connections can be found almost everywhere.[125] The United Nations International Telecommunication Union ranks Greece among the top 30 countries with a highly developed information and communications infrastructure. [126]

Science and technology

The General Secretariat for Research and Technology of the Ministry of Development is responsible for designing, implementing and supervising national research and technological policy. In 2003, public spending on research and development (R&D) was 456.37 million euros (12.6% increase from 2002). Total R&D spending (both public and private) as a percentage of GDP had increased considerably since the beginning of the past decade, from 0.38% in 1989, to 0.65% in 2001. R&D spending in Greece remained lower than the EU average of 1.93%, but, according to Research DC, based on OECD and Eurostat data, between 1990 and 1998, total R&D expenditure in Greece enjoyed the third-highest increase in Europe, after Finland and Ireland. Because of its strategic location, qualified workforce and political and economic stability, many multinational companies such as Ericsson, Siemens, Motorola and Coca-Cola have their regional research and development headquarters in Greece.

Greece's technology parks with incubator facilities include the Science and Technology Park of Crete (Heraklion), the Thessaloniki Technology Park, the Lavrio Technology Park and the Patras Science Park. Greece has been a member of the European Space Agency (ESA) since 2005.[127] Cooperation between ESA and the Hellenic National Space Committee began in the early 1990s. In 1994 Greece and ESA signed their first cooperation agreement. Having formally applied for full membership in 2003, Greece became the ESA's sixteenth member on 16 March 2005. As member of the ESA, Greece participates in the agency's telecommunication and technology activities, and the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security Initiative.

Demographics

The official statistical body of Greece is the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). According to the ELSTAT, Greece's total population in 2001 was 10,964,020.[128] That figure is divided into 5,427,682 males and 5,536,338 females.[128] The preliminary results of the 2011 census show a decrease in the country's population to 10,787,690, a drop of 1.6%.[7] As statistics from 1971, 1981, and 2001 show, the Greek population has been aging the past several decades.[128]

The birth rate in 2003 stood 9.5 per 1,000 inhabitants (14.5 per 1,000 in 1981). At the same time the mortality rate increased slightly from 8.9 per 1,000 inhabitants in 1981 to 9.6 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2003. In 2001, 16.71% of the population were 65 years old and older, 68.12% between the ages of 15 and 64 years old, and 15.18% were 14 years old and younger.[128]

Greek society has also rapidly changed with the passage of time. Marriage rates kept falling from almost 71 per 1,000 inhabitants in 1981 until 2002, only to increase slightly in 2003 to 61 per 1,000 and then fall again to 51 in 2004.[128] Divorce rates on the other hand, have seen an increase – from 191.2 per 1,000 marriages in 1991 to 239.5 per 1,000 marriages in 2004.[128]

Cities

Almost two-thirds of the Greek people live in urban areas. Greece's largest and most influential metropolitan centres are those of Athens and Thessaloniki, with metropolitan populations of approximately 4 million and 1 million inhabitants respectively. Other prominent cities with urban populations above 100,000 inhabitants include those of Patras, Heraklion, Larissa, Volos, Rhodes, Ioannina, Chania and Chalcis.[129]

The table below lists the largest cities in Greece, by population contained in their respective contiguous built up urban areas; which are either made up of many municipalities, evident in the cases of Athens and Thessaloniki, or are contained within a larger single municipality, case evident in most of the smaller cities of the country. The results come from the population census that took place in Greece in May 2011.

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Athens  Thessaloniki |

1 | Athens | Attica | 3,155,000 | 11 | Serres | Central Macedonia | 58,287 |  Patras  Piraeus |

| 2 | Thessaloniki | Central Macedonia | 815,000 | 12 | Alexandroupoli | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 57,812 | ||

| 3 | Patras | Western Greece | 177,071 | 13 | Xanthi | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 56,122 | ||

| 4 | Piraeus | Attica | 168,151 | 14 | Katerini | Central Macedonia | 55,997 | ||

| 5 | Heraklion | Crete | 163,688 | 15 | Kalamata | Peloponnese | 54,100 | ||

| 6 | Larissa | Thessaly | 148,562 | 16 | Kavala | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 54,027 | ||

| 7 | Volos | Thessaly | 85,803 | 17 | Chania | Crete | 53,910 | ||

| 8 | Ioannina | Epirus | 65,574 | 18 | Lamia | Central Greece | 52,006 | ||

| 9 | Trikala | Thessaly | 61,653 | 19 | Komotini | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 50,990 | ||

| 10 | Chalcis | Central Greece | 59,125 | 20 | Rhodes | South Aegean | 49,541 | ||

Migration

Throughout the 20th century, millions of Greeks migrated to the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and Germany, creating a thriving Greek diaspora. Net migration started to show positive numbers from the 1970s, but until the beginning of the 1990s, the main influx was that of returning Greek migrants.[135]

In 1986 legal and unauthorized immigrants totaled approximately 90,000. A study from the mmo.gr Mediterranean Migration Observatory maintains that the 2001 census recorded 762,191 persons residing in Greece without Greek citizenship, constituting around 7% of total population. Of the non-citizen residents, 48,560 were EU or European Free Trade Association nationals and 17,426 were Cypriots with privileged status. The majority come from Eastern European countries: Albania (56%), Bulgaria (5%) and Romania (3%), while migrants from the former Soviet Union (Georgia, Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, etc.) comprise 10% of the total.[136] The greatest cluster of non-EU immigrant population are the larger urban centers, especially the Municipality of Athens, with 132,000 immigrants comprising 17% of the local population, and then Thessaloniki, with 27,000 immigrants reaching 7% of the local population. There is also a considerable number of co-ethnics that came from the Greek communities of Albania and the former Soviet Union.[135]

Greece, together with Italy and Spain, faces a large influx of illegal immigrants trying to enter the EU. The Cabinet has approved a draft law that would allow children born in Greece to immigrant parents to apply for Greek citizenship, so long as one of them has been living in the country legally for at least five consecutive years.[137]

Religion

The Greek Constitution recognizes the Orthodox Christian faith as the "prevailing" faith of the country, while guaranteeing freedom of religious belief for all.[70] The Greek government does not keep statistics on religious groups and censuses do not ask for religious affiliation. According to the U.S. State Department, an estimated 97% of Greek citizens identify themselves as Orthodox Christians, belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church.[138] In a Eurostat – Eurobarometer 2005 poll, 81% of Greek citizens responded that they "believe there is a God",[139] which was the third highest percentage among EU members behind only Malta and Cyprus.[139] According to other sources, 15.8% of Greeks describe themselves as "very religious", which is the highest among all European countries. The survey also found that just 3.5% never attend a church, compared to 4.9% in Poland and 59.1% in the Czech Republic.[140]

Estimates of the recognized Greek Muslim minority, which is mostly located in Thrace, range from 98,000 to 140,000,[138][141] (between 0.9% and 1.2%) while the immigrant Muslim community numbers between 200,000 and 300,000. Albanian immigrants to Greece are usually associated with the Muslim religion, although most are secular in orientation.[142] Following the 1919–1922 Greco-Turkish War and the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Greece and Turkey agreed to a population transfer based on cultural and religious identity. About 500,000 Muslims from Greece, predominantly Turks, but also other Muslims, were exchanged with approximately 1,500,000 Greeks from Asia Minor (now Turkey).[143]

Athens is the only EU capital without a purpose-built place of worship for its Muslim population.[144][145]

Judaism has existed in Greece for more than 2,000 years. Sephardi Jews used to have a large presence in the city of Thessaloniki (by 1900, some 80,000, or more than half of the population, were Jews),[146] but nowadays the Greek-Jewish community who survived German occupation and the Holocaust, during World War II, is estimated to number around 5,500 people.[138][141]

Greek members of Roman Catholic faith are estimated at 50,000[138][141] with the Roman Catholic immigrant community approximating 200,000.[138] Old Calendarists account for 500,000 followers.[141] Protestants, including Greek Evangelical Church and Free Evangelical Churches, stand at about 30,000.[138][141] Assemblies of God, International Church of the Foursquare Gospel and other Pentecostal churches of the Greek Synod of Apostolic Church has 12,000 members.[147] Independent Free Apostolic Church of Pentecost is the biggest Protestant denomination in Greece with 120 churches.[148] There are not official statistics about Free Apostolic Church of Pentecost, but the Orthodox Church estimates the followers as 20,000.[149] The Jehovah's Witnesses report having 28,859 active members.[138][141][150]

Languages

The first concrete evidence of the Greek language dates back to 15th century BC and the Linear B script which is associated with the Mycenaean Civilization. Greek was a widely spoken lingua franca in the Mediterranean world and beyond during Classical Antiquity, and would eventually become the official parlance of the Byzantine Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuries there was a major dispute known as Greek language question, on whether the official language of Greece should be the archaic Katharevousa, created in the 19th century and used as the state and scholarly language, or the Dimotiki, the form of the Greek language which evolved naturally from Byzantine Greek and was the language of the people. The dispute was finally resolved in 1976, when Dimotiki was made the only official variation of the Greek language, and Katharevousa fell to disuse.

Greece is today relatively homogeneous in linguistic terms, with a large majority of the native population using Greek as their first or only language. Among the Greek-speaking population, speakers of the distinctive Pontic dialect came to Greece from Asia Minor after the Greek genocide and constitute a sizable group.

The Muslim minority in Thrace, which amounts to approximately 0.95% of the total population, consists of speakers of Turkish, Bulgarian (Pomaks)[152] and Romani. Romani is also spoken by Christian Roma in other parts of the country. Further minority languages have traditionally been spoken by regional population groups in various parts of the country. Their use has decreased radically in the course of the 20th century through assimilation with the Greek-speaking majority. Today they are only maintained by the older generations and are on the verge of extinction. This goes for the Arvanites, an Albanian-speaking group mostly located in the rural areas around the capital Athens, and for the Aromanians and Moglenites, also known as Vlachs, whose language is closely related to Romanian and who used to live scattered across several areas of mountaneous central Greece. Members of these groups ethnically identify as Greeks[153] and are today all at least bilingual in Greek.

Near the northern Greek borders there are also some Slavic–speaking groups, locally known as Slavomacedonian-speaking, most of whose members identify ethnically as Greeks. Their dialects can be linguistically classified as forms of either Macedonian Slavic or Bulgarian.[154][155] It is estimated that in the aftermath of the population exchanges of 1923 there were somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000 Slavic speakers in Greek Macedonia.[62] The Jewish community in Greece traditionally spoke Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), today maintained only by a small group of a few thousand speakers.[citation needed]

Education

Compulsory education in Greece comprises primary schools (Δημοτικό Σχολείο, Dimotikó Scholeio) and gymnasium (Γυμνάσιο). Nursery schools (Παιδικός σταθμός, Paidikós Stathmós) are popular but not compulsory. Kindergartens (Νηπιαγωγείο, Nipiagogeío) are now compulsory for any child above 4 years of age. Children start primary school aged 6 and remain there for six years. Attendance at gymnasia starts at age 12 and last for three years.

Greece's post-compulsory secondary education consists of two school types: unified upper secondary schools (Γενικό Λύκειο, Genikό Lykeiό) and technical–vocational educational schools (Τεχνικά και Επαγγελματικά Εκπαιδευτήρια, "TEE"). Post-compulsory secondary education also includes vocational training institutes (Ινστιτούτα Επαγγελματικής Κατάρτισης, "IEK") which provide a formal but unclassified level of education. As they can accept both Gymnasio (lower secondary school) and Lykeio (upper secondary school) graduates, these institutes are not classified as offering a particular level of education.

Public higher education is divided into universities, "Highest Educational Institutions" (Ανώτατα Εκπαιδευτικά Ιδρύματα, Anótata Ekpaideytiká Idrýmata, "ΑΕΙ") and "Highest Technological Educational Institutions" (Ανώτατα Τεχνολογικά Εκπαιδευτικά Ιδρύματα,Anótata Technologiká Ekpaideytiká Idrýmata, "ATEI"). Students are admitted to these Institutes according to their performance at national level examinations taking place after completion of the third grade of Lykeio. Additionally, students over twenty-two years old may be admitted to the Hellenic Open University through a form of lottery. The Capodistrian University of Athens is the oldest university in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Greek education system also provides special kindergartens, primary and secondary schools for people with special needs or difficulties in learning. Specialist gymnasia and high schools offering musical, theological and physical education also exist.

Health

The Greek healthcare system is universal and is ranked as one of the best in the world. In a 2000 World Health Organization report it was ranked 14th in the overall assessment and 11th at quality of service, surpassing countries such as the United Kingdom (18th) and Germany (25th).[156] In 2010, there were 138 hospitals with 31,000 beds in the country, but on 1 July 2011, the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity announced its plans to decrease the number to 77 hospitals with 36,035 beds, as a necessary reform to reduce expenses and further enhance healthcare standards.[157] Greece's healthcare expenditures as a percentage of GDP were 9.6% in 2007 according to a 2011 OECD report, just above the OECD average of 9.5%.[158] The country has the largest number of doctors-to-population ratio of any OECD country.[158]

Life expectancy in Greece is 80.3 years, above the OECD average of 79.5.[158] and among the highest in the world. The same OECD report showed that Greece had the largest percentage of adult daily smokers of any of the 34 OECD members.[158] The country's obesity rate is 18.1%, which is above the OECD average of 15.1% but considerably below the American rate of 27.7%.[158] In 2008, Greece had the highest rate of perceived good health in the OECD, at 98.5%.[159] Infant mortality is one of the lowest in the developed world with a rate of 3.1 deaths per 1,000 live births.[158]

Culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Mycenaean Greece and continuing most notably into Classical Greece, through the influence of the Roman Empire and its Greek Eastern successor, the Byzantine Empire. Other cultures and nations, such as the Latin and Frankish states, the Ottoman Empire, the Venetian Republic, the Genoese Republic, and the British Empire have also left their influence on modern Greek culture, although historians credit the Greek War of Independence with revitalising Greece and giving birth to a single, cohesive entity of its multi-faceted culture.

Philosophy

Most western philosophical traditions began in Ancient Greece in the 6th century BC. The first philosophers are called "Presocratics," which designates that they came before Socrates, whose contributions mark a turning point in western thought. The Presocratics were from the western or the eastern colonies of Greece and only fragments of their original writings survive, in some cases merely a single sentence.

A new period of philosophy started with Socrates. Like the Sophists, he rejected entirely the physical speculations in which his predecessors had indulged, and made the thoughts and opinions of people his starting-point. Aspects of Socrates were first united from Plato, who also combined with them many of the principles established by earlier philosophers, and developed the whole of this material into the unity of a comprehensive system.

Aristotle of Stagira, the most important disciple of Plato, shared with his teacher the title of the greatest philosopher of antiquity. But while Plato had sought to elucidate and explain things from the supra-sensual standpoint of the forms, his pupil preferred to start from the facts given us by experience. Except from these three most significant Greek philosophers other known schools of Greek philosophy from other founders during ancient times were Stoicism, epicureanism, Skepticism and Neoplatonism.[160]

Literature

The timeline of the Greek literature can be separated into three big periods: the ancient, the Byzantine and the modern Greek literature.

At the beginning of Greek literature stand the two monumental works of Homer: the Iliad and the Odyssey. Though dates of composition vary, these works were fixed around 800 BC or after. In the classical period many of the genres of western literature became more prominent. Lyrical poetry, odes, pastorals, elegies, epigrams; dramatic presentations of comedy and tragedy;historiography, rhetorical treatises, philosophical dialectics, and philosophical treatises all arose in this period.The two major lyrical poets were Sappho and Pindar. The Classical era also saw the dawn of drama.

Of the hundreds of tragedies written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors have survived: those of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The surviving plays by Aristophanes are also a treasure trove of comic presentation, while Herodotus and Thucydides are two of the most influential historians in this period. The greatest prose achievement of the 4th century was in philosophy with the works of the three great philosophers.

Byzantine literature refers to literature of the Byzantine Empire written in Atticizing, Medieval and early Modern Greek, and it is the expression of the intellectual life of the Byzantine Greeks during the Christian Middle Ages.

Modern Greek literature refers to literature written in common Modern Greek, emerging from late Byzantine times in the 11th century. The Cretan Renaissance poem Erotokritos is undoubtedly the masterpiece of this period of Greek literature. It is a verse romance written around 1600 by Vitsentzos Kornaros(1553–1613). Later, during the period of Greek enlightenment (Diafotismos), writers such as Adamantios Korais and Rigas Feraios will prepare with their works the Greek Revolution (1821–1830).

Leading literary figures of modern Greece include Dionysios Solomos, Andreas Kalvos, Angelos Sikelianos, Emmanuel Rhoides, Kostis Palamas, Penelope Delta, Yannis Ritsos, Alexandros Papadiamantis, Nikos Kazantzakis, Andreas Embeirikos, Kostas Karyotakis, Gregorios Xenopoulos, Constantine P. Cavafy, and Demetrius Vikelas. Two Greek authors have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature: George Seferis in 1963 and Odysseas Elytis in 1979.

Cinema

Cinema first appeared in Greece in 1896 but the first actual cine-theatre was opened in 1907. In 1914 the Asty Films Company was founded and the production of long films begun. Golfo (Γκόλφω), a well known traditional love story, is considered the first Greek feature film, although there were several minor productions such as newscasts before this. In 1931 Orestis Laskos directed Daphnis and Chloe (Δάφνις και Χλόη), contained the first nude scene in the history of European cinema; it was also the first Greek movie which was played abroad. In 1944 Katina Paxinou was honoured with the Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for For Whom the Bell Tolls.

The 1950s and early 1960s are considered by many as the Greek Golden age of Cinema. Directors and actors of this era were recognized as important historical figures in Greece and some gained international acclaim: Mihalis Kakogiannis, Alekos Sakellarios, Melina Mercouri, Nikos Tsiforos, Iakovos Kambanelis, Katina Paxinou, Nikos Koundouros, Ellie Lambeti, Irene Papas etc. More than sixty films per year were made, with the majority having film noir elements . Notable films were Η κάλπικη λίρα (1955 directed by Giorgos Tzavellas), Πικρό Ψωμί (1951, directed by Grigoris Grigoriou), O Drakos (1956 directed by Nikos Koundouros), Stella (1955 directed by Cacoyannis and written by Kampanellis). Cacoyannis also directed Zorba the Greek with Anthony Quinn which received Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Film nominations. Finos Film also contributed to this period with movies such as Λατέρνα, Φτώχεια και Φιλότιμο, Madalena, Η Θεία από το Σικάγο, Το ξύλο βγήκε από τον Παράδεισο and many more. During the 1970s and 1980s Theo Angelopoulos directed a series of notable and appreciated movies. His film Eternity and a Day won the Palme d'Or and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival.

There were also internationally renowned filmmakers in the Greek diaspora such as the Greek-American Elia Kazan.

Cuisine

Greek cuisine is as an example of the healthy Mediterranean diet (Cretan diet).[161] Greek cuisine incorporates fresh ingredients into a variety of local dishes such as moussaka, stifado, Greek salad, spanakopita and souvlaki. Some dishes can be traced back to ancient Greece like skordalia[citation needed] (a thick purée of walnuts, almonds, crushed garlic and olive oil), lentil soup, retsina (white or rosé wine sealed with pine resin) and pasteli (candy bar with sesame seeds baked with honey). Throughout Greece people often enjoy eating from small dishes such as meze with various dips such as tzatziki, grilled octopus and small fish, feta cheese, dolmades(rice, currants and pine kernels wrapped in vine leaves), various pulses, olives and cheese. Olive oil is added to almost every dish.

Sweet desserts such as galaktoboureko, and drinks such as ouzo, metaxa and a variety of wines including retsina. Greek cuisine differs widely from different parts of the mainland and from island to island. It uses some flavorings more often than other Mediterranean cuisines: oregano, mint, garlic, onion, dill and bay laurel leaves. Other common herbs and spices include basil, thyme and fennelseed. Many Greek recipes, especially in the northern parts of the country, use "sweet" spices in combination with meat, for example cinnamon and cloves in stews.

Music

Greek vocal music extends far back into ancient times where mixed-gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons. Instruments during that period included the double-reed aulos and the plucked string instrument, the lyre, especially the special kind called a kithara. Music played an important role in the education system during ancient times. Boys were taught music from the age of six. Later influences from the Roman Empire, Middle East and the Byzantine Empire had also effect on Greek music.

While the new technique of polyphony was developing in the West, the Eastern Orthodox Church resisted any type of change. Therefore, Byzantine music remained monophonic and without any form of instrumental accompaniment. As a result, and despite certain attempts by certain Greek chanters (such as Manouel Gazis, Ioannis Plousiadinos or the Cypriot Ieronimos o Tragoudistis), Byzantine music was deprived of elements of which in the West encouraged an unimpeded development of art. However, this method which kept music away from polyphony, along with centuries of continuous culture, enabled monophonic music to develop to the greatest heights of perfection. Byzantium presented the monophonic Byzantine chant; a melodic treasury of inestimable value for its rhythmical variety and expressive power.

Along with the Byzantine (Church) chant and music, the Greek people also cultivated the Greek folk song which is divided into two cycles, the akritic and klephtic. The akritic was created between the 9th and 10th centuries. and expressed the life and struggles of the akrites (frontier guards) of the Byzantine empire, the most well known being the stories associated with Digenes Akritas. The klephtic cycle came into being between the late Byzantine period and the start of the Greek War of Independence. The klephtic cycle, together with historical songs, paraloghes (narrative song or ballad), love songs, mantinades, wedding songs, songs of exile and dirges express the life of the Greeks. There is a unity between the Greek people's struggles for freedom, their joys and sorrow and attitudes towards love and death.

The Heptanesean kantádhes (καντάδες 'serenades'; sing.: καντάδα) became the forerunners of the Greek modern song, influencing its development to a considerable degree. For the first part of the next century, several Greek composers continued to borrow elements from the Heptanesean style. The most successful songs during the period 1870–1930 were the so-called Athenian serenades, and the songs performed on stage (επιθεωρησιακά τραγούδια 'theatrical revue songs') in revue, operettas and nocturnes that were dominating Athens' theater scene.