Green algae

| Green algae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

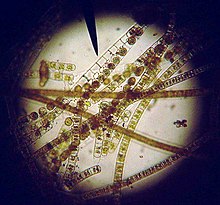

The green algae (singular: green alga) are the large group of algae from which the embryophytes (higher plants) emerged.[1] As such, they form a paraphyletic group, although the group including both green algae and embryophytes is monophyletic (and often just known as kingdom Plantae). The green algae include unicellular and colonial flagellates, most with two flagella per cell, as well as various colonial, coccoid, and filamentous forms, and macroscopic seaweeds. In the Charales, the closest relatives of higher plants, full differentiation of tissues occurs. There are about 6,000 species of green algae.[2] Many species live most of their lives as single cells, while other species form colonies, coenobia, long filaments, or highly differentiated macroscopic seaweeds.

A few other organisms rely on green algae to conduct photosynthesis for them. The chloroplasts in euglenids and chlorarachniophytes were acquired from ingested green algae,[1] and in the latter retain a vestigial nucleus (nucleomorph). Green algae are also found symbiotically in the ciliate Paramecium, and in Hydra viridis and flatworms. Some species of green algae, particularly of genera Trebouxia and Pseudotrebouxia (Trebouxiophyceae), can be found in symbiotic associations with fungi to form lichens. In general the fungal species that partner in lichens cannot live on their own, while the algal species is often found living in nature without the fungus. Trentepohlia is a green alga living on humid soil, rocks or tree bark.

Cellular structure

Almost all forms have chloroplasts. These contain chlorophylls a and b, giving them a bright green color (as well as the accessory pigments beta carotene and xanthophylls),[3] and have stacked thylakoids.[4]

All green algae have mitochondria with flat cristae. When present, flagella are typically anchored by a cross-shaped system of microtubules and fibrous strands, but these are absent among the higher plants and charophytes, which instead have a 'raft' of microtubules, the spline. Flagella are used to move the organism. Green algae usually have cell walls containing cellulose, and undergo open mitosis without centrioles.

Origins

The chloroplasts of green algae are bound by a double membrane, so presumably they were acquired by direct endosymbiosis of cyanobacteria. A number of cyanobacteria show similar pigmentation (e.g., Prochloron), and cyanobacterial endosymbiosis appears to have arisen more than once[citation needed], as in the Glaucophyta (Cyanophora) and red algae. Indeed, the green algae probably obtained their chloroplasts from a Prochloron-type prokaryotic ancestor, and evolved separately from the red algae.

Classification

Green algae are often classified with their embryophyte descendants in the green plant clade Viridiplantae (or Chlorobionta). Viridiplantae, together with red algae and glaucophyte algae, form the supergroup Primoplantae, also known as Archaeplastida or Plantae sensu lato.

Classification systems which have a kingdom of Protista may include green algae in the Protista or in the Plantae.[5]

Phylogeny:[6]

The orders outside the Chlorophyta are often grouped as the division Charophyta, which is paraphyletic to higher plants, together comprising the Streptophyta. Sometimes the Charophyta is restricted to the Charales, and a division Gamophyta is introduced for the Zygnematales and Desmidiales. In older systems the Chlorophyta may be taken to include all the green algae, but taken as above they appear to form a monophyletic group.

One of the most basal green algae is the flagellate Mesostigma, although it is not yet clear whether it is sister to all other green algae, or whether it is one of the more basal members of the Streptophyta.[1][7]

Reproduction

Green algae are eukaryotic organisms that follow a reproduction cycle called alternation of generations.

Reproduction varies from fusion of identical cells (isogamy) to fertilization of a large non-motile cell by a smaller motile one (oogamy). However, these traits show some variation, most notably among the basal green algae called prasinophytes.

Haploid algae cells (containing only one copy of their DNA) can fuse with other haploid cells to form diploid zygotes. When filamentous algae do this, they form bridges between cells, and leave empty cell walls behind that can be easily distinguished under the light microscope. This process is called conjugation.

The species of Ulva are reproductively isomorphic, the diploid vegetative phase is the site of meiosis and releases haploid zoospores, which germinate and grow producing a haploid phase alternating with the vegetative phase.[8]

Chemistry

The green algae span a wide range of δ13C values, with different groups having different typical ranges.

| Algal group | δ13C range[9] |

|---|---|

| HCO3-using red algae | −22.5‰ to −9.6‰ |

| CO2-using red algae | −34.5‰ to −29.9‰ |

| Brown algae | −20.8‰ to −10.5‰ |

| Green algae | −20.3‰ to −8.8‰ |

Physiology

The green algae, including the characean algae, have served as model experimental organisms to understand the mechanisms of the ionic and water permeability of membranes, osmoregulation, turgor regulation, salt tolerance, cytoplasmic streaming, and the generation of action potentials.[10]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Jeffrey D. Palmer, Douglas E. Soltis and Mark W. Chase (2004). "The plant tree of life: an overview and some points of view". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1437–1445. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1437. PMID 21652302.

- ^ Thomas, D. 2002. Seaweeds. The Natural History Museum, London. ISBN 0-565-09175-1

- ^ Burrows 1991. Seaweeds of the British Isles. Volume 2 Natural History Museum, London. ISBN 0-565-00981-8

- ^ Hoek, C. van den, Mann, D.G. and Jahns, H.M. 1995. Algae An introduction to phycology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-30419-9

- ^ T Cavalier-Smith (1993 December). "Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla". Microbiol Rev. 57 (4): 953–994. PMC 372943. PMID 8302218.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lewis, L. A & R. M. McCourt (2004). "Green algae and the origin of land plants". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1535–1556. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. PMID 21652308.

- ^ Andreas Simon, Gernot Glöckner, Marius Felder, Michael Melkonian and Burkhard Becker (2006). "EST analysis of the scaly green flagellate Mesostigma viride (Streptophyta): Implications for the evolution of green plants (Viridiplantae)". BMC Plant Biology. 6 (2): 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-6-2. PMC 1413533. PMID 16476162.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ Maberly, S. C.; Raven, J. A.; Johnston, A. M. (1992). "Discrimination between 12C and 13C by marine plants". Oecologia. 91 (4): 481. doi:10.1007/BF00650320. JSTOR 4220100.

- ^ Tazawa, Masashi (2010). "Sixty Years Research with Characean Cells: Fascinating Material for Plant Cell Biology". Progress in Botany. 72: 5–34. Retrieved 7-10-2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)