Competition between Airbus and Boeing

Competition between Airbus and Boeing is a result of the two companies' duopoly in the large jet airliner market since the 1990s, a consequence of mergers within the global aerospace industry over the years. Airbus began as a consortium from Europe, whereas the American Boeing took over its former arch-rival, McDonnell Douglas, when the latter became defunct and merged with the former in 1997. Other manufacturers, such as Lockheed Martin and Convair in the United States and British Aerospace, Dornier and Fokker in Europe, have pulled out of the civil aviation market after economic problems and declining sales.

The 1990s changes in the Eastern Bloc and the former Soviet Union has put its aircraft industry in a disadvantaged position, although Antonov, Ilyushin, Irkut, Sukhoi, Tupolev, Yakovlev and the newly merged United Aircraft Corporation continue to develop new passenger aircraft and maintain a small market share. The Chinese aviation industry is currently developing and producing two jet- (state owned merge Comac) and several turboprop-powered airliners in increasing but still small quantities, also two wide-bodies are proposed.

Airbus and Boeing since the end of the 1990s possess a duopoly[1] in the global market for large commercial jets comprising narrow-body aircraft, wide-body aircraft and jumbo jets. However, Embraer has gained market share with their narrow-body aircraft in the Embraer E-jets series. There is also a similar competition in regional jet manufacturing between Bombardier Aerospace and Embraer.

In the last 10 years (2002–2011), Airbus has received 7,181 orders while delivering 4,218, Boeing won 6,360 orders while delivering 3,871. Competition is intense; each company regularly accuses the other of receiving unfair state aid from their respective governments.

Competition by product

Range overlap

Though both manufacturers have a broad product range varying from single-aisle to wide-body, they do not always compete head-to-head. As listed below they respond with slightly different models.

- The Airbus A380, for example, is substantially larger than the Boeing 747.

- The Airbus A350 competes with the high end of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Boeing 777.

- The Airbus A320 is larger than the Boeing 737-700 but smaller than the 737-800.

- The Airbus A321 is larger than the Boeing 737-900 but smaller than the previous Boeing 757-200.

- The Airbus A330-200 competes with the similar Boeing 767-400ER and the Boeing 777-200ER.

Airlines benefit from this competition as they get an array of diversified products ranging from 100-500 seats, than if both companies offered identical aircraft.

Passengers/range km (statute miles) for all models

| 2,645 to 3,800 km (2400 sm) | 4,400 to 5,900 km (3500 sm) | 6,800 to 7,700 km (4500 sm) | 8,704 to 10,200 km (5900 sm) | 10,500 to 11,300 km (6800 sm) | 12,250 to 12,500 km (7700 sm) | 13,300 to 13,900 km (8500 sm) | 14,200 to 14,800 km (9000 sm) | 14,900 to 15,200 km (9300 sm) | 15,400 to 16,000 km (9800 sm) | 16,700 to 17,400 km (10500 sm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-139 | (717-200) | A318-100 737-600 | |||||||||

| 140-156 | 737-700 (727-100) | A319-100 (707-020) | 737-700ER | ||||||||

| 148-189 | 737-800 A320-200 (727-200) | (707-120) | |||||||||

| 177-255 | A321-200 737-900 | (757-200) | (A310-200) (A310-300) | 767-300ER (707-320) | 767-200ER | 787-8 | |||||

| 243-375 | (757-300) | 767-400ER 747SP | |||||||||

| 253-300 | (A300) | (A300-600) | A330-200 | A340-200 | A350-800 787-9 | ||||||

| 295-440 | 777-200 | A330-300 | A340-300 | 777-200ER | A350-900 | 777-200LR | |||||

| 313-366 | A340-500 | A340-500HGW A350-900R | |||||||||

| 358-550 | 747-100SR 747-300SR | 747-100 | 777-300 | 747-200 | 777-300ER A350-1000 | ||||||

| 380-419 | 747-300 | A340-600 A340-600HGW | |||||||||

| 410-568 | 747-400 | 747-400ER | |||||||||

| 467-605 | 747-8 | ||||||||||

| 525-853 | A380 |

Airbus A320 vs Boeing 737

| Airbus A320 family | Boeing 737 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A318 | A319 | A320 | A321 | 737-300 | 737-400 | 737-500 | 737-600 | 737-700 | 737–800 | 737-900ER | |

| Two | Cockpit crew | Two | |||||||||

| 117 (1-class) | 142 (1-class) | 180 (1-class) | 220 (1-class) | Seating capacity | 148 (1-class) | 168 (1-class) | 132 (1-class) | 149 (1-class) | 189 (1-class) | 204 (1-class) | |

| 31.45 m (103 ft 2 in) | 33.84 m (111 ft) | 37.57 m (123 ft) | 44.51 m (146 ft) | Length | 28.6 m (94 ft) | 36.5 m (119 ft 6 in) | 31.1 m (101 ft 8 in) | 31.2 m (102 ft 6 in) | 33.6 m (110 ft 4 in) | 39.5 m (129 ft 6 in) | 42.1 m (138 ft 2 in) |

| 12.56 m (41 ft 2 in) | 11.76 m (38 ft 7 in) | Height | 11.3 m (37 ft) | 11.1 m (36 ft 5 in) | 12.6 m (41 ft 3 in) | 12.5 m (41 ft 2 in) | |||||

| 34.1 m (111 ft 10 in) | Wingspan | 28.3 m (93 ft) | 28.9 m (94 ft 8 in) | 34.3 m (112 ft 7 in) | |||||||

| 25° | Wing Sweepback | 25° | 25.02° | ||||||||

| Aspect Ratio | 8.83 | 9.16 | 9.45 | ||||||||

| 3.70 m (12 ft 1 in) | Cabin Width | 3.54 m (11 ft 7 in) | |||||||||

| Cabin Height | 2.20 m (7 ft 3 in) | ||||||||||

| 3.95 m (13 ft) | Fuselage Width | 3.76 m (12 ft 4 in) | |||||||||

| 4.14 m[2] | Fuselage Height | 4.11 m (13' 6") | |||||||||

| 39,300 kg | 40,600 kg | 42,400 kg | 48,200 kg | Typical empty weight | 28,120 kg (61,864 lb) | 33,200 kg (73,040 lb) | 31,300 kg (68,860 lb) | 36,378 kg (80,031 lb) | 38,147 kg (84,100 lb) | 41,413 kg (91,108 lb) | 44,676 kg (98,495 lb) |

| 68,000 kg (149,900 lb) | 75,500 kg (166,500 lb) | 77,000 kg (169,000 lb) | 93,500 kg (206,100 lb) | Maximum take-off weight | 49,190 kg (108,218 lb) | 68,050 kg (149,710 lb) | 60,550 kg (133,210 lb) | 66,000 kg (145,500 lb) | 70,080 kg (154,500 lb) | 79,010 kg (174,200 lb) | 85,130 kg (187,700 lb) |

| Maximum landing weight | 44,906 kg (99,000 lb) | 56,246 kg (124,000 lb) | 49,895 kg (110,000 lb) | 55,112 kg (121,500 lb) | 58,604 kg (128,928 lb) | 66,361 kg (146,300 lb) | |||||

| Maximum zero-fuel weight | 40,824 kg (90,000 lb) | 53,070 kg (117,000 lb) | 46,720 kg (103,000 lb) | 51,936 kg (114,500 lb) | 55,202 kg (121,700 lb) | 62,732 kg (138,300 lb) | |||||

| Cargo Capacity | 18.4 m³ (650 ft³) | 38.9 m³ (1,373 ft³) | 23.3 m³ (822 ft³) | 21.4 m³ (756 ft³) | 27.3 m³ (966 ft³) | 45.1 m³ (1,591 ft³) | 52.5 m³ (1,852 ft³) | ||||

| 1,355 m (4,446 ft) |

1,950 m (6,398 ft) |

2,090 m (6,857 ft) |

2,180 m (7,152 ft) |

Takeoff run at MTOW | 1,990 m (6,646 ft) | 2,540 m (8,483 ft) | 2,470 m (8,249 ft) | 2,400 m (8,016 ft) | 2,480 m (8,283 ft) | 2,450 m (8,181 ft) | |

| .78 Mach | Cruising speed | .74 Mach | .74 Mach | .785 Mach | .78 Mach | ||||||

| .82 Mach | Max. speed | .82 Mach | |||||||||

| 5,950 km (3,200 nm) |

6,800 km (3,700 nm) |

5,700 km (3,078 nm) |

5,600 km (3,050 nm) |

Range fully loaded | 3,440 km (1,860 nm) |

4,005 km (2,165 nm) |

4,444 km (2,402 nm) |

5,648 km (3,050 nm) |

6,230 km (3,365 nm) (5,510 nm on ER variants.) |

5,665 km (3,060 nm) |

4,996 km (2,700 nm) [5,925 km (3,200 nm ) 2-class layout w/2 aux. tanks] |

| 23,860 L 6,300 US gal |

29,840 L 7,885 US gal |

29,680 L 7,842 US gal |

Max. fuel capacity | 17,860 L 4,725 US gal |

23,170 L 6,130 US gal |

23,800 L 6,296 US gal |

26,020 L 6,875 US gal |

29,660 L 7,837 US gal | |||

| 39,000 ft | Service Ceiling | 35,000 ft | 37,000 ft | 41,000 ft | |||||||

| PW6022A, CFM56-5 | IAE V2500, CFM56-5 | Engines (x2) | CFM56-3B-1 | CFM56-3B-2 | CFM56-3B-1 | CFM56-7B20 | CFM56-7B26 | CFM56-7B27 | CFM56-7B27 | ||

| Max Thrust | 20,000 lbf | 22,000 lbf | 20,000 lbf | 20,600 lbf | 26,300 lbf | 27,300 lbf | |||||

| Engine Ground Clearance | 51 cm (20 in) | 46 cm (18 in) | 48 cm (19 in) | ||||||||

Airbus A330 vs Boeing 767 & 777

| Airbus A330 Series | Boeing 767 Series | Boeing 777 Series | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A330-200 | A330-300 | A330-F | 767-200ER | 767-300ER | 767-300-F | 767-400ER | 777-200ER | |

| Two | Cockpit crew | Two | ||||||

| 253 (3 cl.) 293 (2 cl.) 405 (1-cl.)[3] |

295 (3 cl.) 335 (2 cl.) 440 (1 cl.) |

- | Seating capacity | 181-255 | 218-351 | - | 245-375 | 301-440 |

| 58,8 m (192 ft 11 in) |

63,6 m (208 ft 8 in) |

58.8 m (192 ft 11 in) | Length | 48.5m | 54.9m | 61.4m | 63.7m | |

| 17.40 m | 16.9 m (55 ft 5 in) | Height | 15.8m | 15.9m | 16.8m | 18.5m | ||

| 60.3 m (197 ft 10 in) | Wingspan | 47.6m | 51.9m | 60.9m | ||||

| 5.28 m (17 ft 4 in) | Cabin Width | |||||||

| 5.64 m (18 ft 6 in) | Hull Width | 5.03 m[4] | ||||||

| 233,000 kg (513,700 lb) | Maximum take-off weight | 179,170 kg (395,000 lb) | 186,880 kg (412,000 lb) | 204,110 kg (450,000 lb) | 297,550 kg (656,000 lb) | |||

| 182,000 kg (401,200 lb) | 187,000 kg (412,300 lb) | Maximum landing weight | ||||||

| 2,200 m | 2,500 m | Takeoff run | ||||||

| 0.82 Mach (896 km/h) | Cruising speed | 0.80 Mach | 0.84 Mach | |||||

| 0.85 Mach (913 km/h or 490 knots at 35,000 ft.) | Max Speed | 0.86 Mach | 0.89 Mach | |||||

| 12,500 km (6,750 nm) | 10,500 km (5,670 nm) | 7,400 km (4,000 nm) | Range fully loaded | 12,250 km (6,600 nm) | 11,300 km (6,100 nm) | 6,100 km (3,270 nm) | 10,500 km (5,645 nm) | 14,310 km (7,725 nm) |

| 139,100 L (36,750 US gal) |

97,170 L (25,670 US gal) |

139,100 L | Max. fuel capacity | 90,770 L (23,980 US gal) |

171,176 L (45,220 US gal) | |||

| 136 m³ 26 LD3s |

162 m³ 32 LD3s |

475 m³ | Cargo (volume) / ULDs | 81.4 m³ | 106.8 m³ | 454 m³ | 129 m³ | 162 m³ 32 LD3s |

| PW PW4000 GE CF6-80E1 RR Trent 700 |

Engines (x2) |

PW PW4062 GE CF6-80C2B7F |

PW PW4062 GE CF6-80C2B8F |

PW PW4062 GE CF6-80C2B7F RR RB211-524H |

PW PW4062 GE CF6-80C2B7F RR RB211-524H |

PW PW4090 RR RR895 GE 90-94B | ||

| 303-320 kN 68,000-72,000 lbf |

Max Thrust (x2) |

|||||||

| Engine Ground Clearance | 0.56 m (1 ft 10 in) | 0.81 m (2 ft 8 in) | ||||||

Airbus A350 vs Boeing 787 & 777

| A350 | Boeing 777 | Boeing 787 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A350-800[5] | A350-900[6] | A350-1000 | A350-900R[7] | A350-900F | 777-200LR | 777-200F | 777-300ER[8] | 787-8! style="background:#f2f2f2; width:8%;"| 787-9[9] | ||

| Two | Cockpit crew | Two | ||||||||

| 270 | 314 | 350 | 310 | 90t cargo | Passengers (3cl) | 301 | 103t cargo | 365 | 263 | 310[10] |

| 60.7 m | 67.0 m | 74.0 m | 67.0 m | Length | 63.7 m | 73.9 m | 63.0 m | 68.9 m | ||

| 17.2 m | Height | 18.8 m | 18.6 m | 18.7 m | 16.5 m | 17.0 m | ||||

| 64.8 m | Wingspan | 64.8 m | 60.0 m | 60.1 m | ||||||

| 19 ft 6 in (5.96 m)[11] | Fuselage Width | 20 ft 4 in (6.19 m) | 18 ft 11 in (5.75 m) | |||||||

| 18 ft 4 in (5.59 m) | Cabin Width | 19 ft 3 in (5.86 m) | 18 ft (5.49 m) | |||||||

| 31.9° | Wing sweep | 31.64° | 32.2° | |||||||

| 28 | 36 | 44 | LD3 containers | 32[12] | 37 pallets | 44[13] | 36 | 44 | ||

| 248 | 268 | 298 | MTOW (t) | 347.452 | 347.450 | 351.534 | 244.940 | 272.150 | ||

| 185 | 205 | 228.5 | Max landing (t) | 183.7 | 197.3 | |||||

| 115.7[EW 1] | Empty weight (t) | 145.2[EW 2] | 167.8[EW 2] | 115.3[EW 3] | 125[EW 3] | |||||

| 129,000 | 138,000 | 156,000 | Max fuel (l) | 202,287 | 181,280 | 181,280 | 138,700 | 145,000 | ||

| 0.85 | Cruise speed (M) | 0.84 | 0.85 | |||||||

| 0.89 | Max speed (M) | 0.89 | ||||||||

| 75,000 | 84,000 | 93,000 | Thrust (lb) (× 2) | 115,300 | 68,000 | 88,200 | ||||

| RR Trent XWB | Engines | GE90-110B | GE90-115B | RR Trent 1000 or GE GEnx | ||||||

| 8,300 nm 15,400 km | 8,100 nm 15,000 km | 8,000 nm 14,800 km | 9,500 nm 17,600 km | 5,000 nm 9,250 km | Range | 9,420 nm 17,445 km | 4,990 nm 9,065 km | 7,900 nm 14,630 km | 8,500 nm 15,750 km | 7,500 nm[10] 13,890 km |

| $245.5M | $277.7M | $320.6M | TBA | TBA | Price [14][15] | $275.8M | $280.1M | $298.3M | $227.8M | TBA |

Empty weight EW:

- ^ Proposed manufacturer's weight empty including expected overweight.

- ^ a b Final operating empty weight

- ^ a b Proposed operating empty weight not including expected overweight

Airbus A380 vs Boeing 747

| Airbus A380 | Boeing 747 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A380-800[16] | 747-400[17] | 747-400ER[18] | 747-8I[19][20] | |

| Two | Cockpit crew | Two | ||

| 525 / 644 / 853 (3/2/1-class) | Passengers | 416 / 524 (3/2-class) | 467 (3-class) | |

| 73 m | Length | 70.6 m (231 ft 10 in) | 76.4 m (250 ft 8 in) | |

| 24.1 m | Height | 19.4 m (63 ft 8 in) | 19.5 m (64 ft 2 in) | |

| 79.8 m | Wingspan | 64.4 m (211 ft 5 in) | 68.5 m (224 ft 7 in) | |

| Main deck: 6.58 m (21 ft 7 in) Upper Deck: 5.92 m (19 ft 5 in) |

Cabin width | 6.1 m (20.1 ft) | ||

| 633 m² (333 + 300) | Useful cabin-area | |||

| 38 | LD3 containers | 30 | 28 | 36 |

| 276,800 kg (608,400 lb) | Empty weight | 178,756 kg (393,263 lb) | 184,570 kg (406,900 lb) | 214,500 kg (472,900 lb) |

| 361,000 kg (796,000 lb) | Max zero-fuel weight | 246,074 kg | 251,744 kg | 291,000 kg (642,000 lb) |

| 560,000 kg (1,235,000 lb) | MTOW | 396,890 kg (875,000 lb) | 412,775 kg (910,000 lb) | 442,000 kg (974,000 lb) |

| 310,000 L (81,890 US gal) | Max fuel | 216,840 L (57,285 US gal) | 241,140 L (63,705 US gal) | 241,619 L (64,221 US gal) |

| Mach 0.85 (900 km/h) | Cruise speed | Mach 0.85 (567 mph, 912 km/h at altitude) | Mach 0.855, (567 mph, 913 km/h at altitude) | |

| Mach 0.96 (1030 km/h)[21] | Max Operating Mach | Mach 0.92 (987 km/h) | ||

| 311 kN (70,000 lbf) | Thrust (× 4) | 63,300 lbf PW 62,100 lbf GE 59,500 lbf RR |

63,300 lbf PW 62,100 lbf GE |

66,500 lbf |

| GP7270, Trent 970 | Engines | PW 4062 GE CF6-80C2B5F RR RB211-524H |

PW 4062 GE CF6-80C2B5F |

GEnx-2B67 |

| 2,750 m (9,020 ft) | Takeoff run at MTOW | 3,018 m (9,902 ft) | N/A | |

| 15,200 km (8,200 nmi) | Range (3 class) | 13,450 km (7,260 nm) | 14,205 km (7,670 nm) | 14,815 km (8,000 nm) |

| $389.9M | Price [22][23] | $228-260M | $228-260M | $332.9M |

The wide-body Boeing 747-8, the latest modification of Boeing's largest airliner, is notably in direct competition on long-haul routes with the A380, a full-length double-deck aircraft now in service. For airlines seeking very large passenger airliners, the two have been pitched as competitors on various occasions. Following another delay to the A380 programme in October 2006, FedEx and the United Parcel Service canceled their orders for the A380-800 freighter. Some A380 launch customers deferred delivery or considered switching to the 747-8 and 777F aircraft.[24][25]

Boeing's advertising claims the 747-8I to be over 10% lighter per seat and have 11% less fuel consumption per passenger, with a trip-cost reduction of 21% and a seat-mile cost reduction of more than 6%, compared to the A380. The 747-8F's empty weight is expected to be 80 tonnes (88 tons) lighter and 24% lower fuel burnt per ton with 21% lower trip costs and 23% lower ton-mile costs than the A380F.[26] On the other side, Airbus' advertising claims the A380 to have 8% less fuel consumption per passenger than the 747-8I and emphasizes the longer range of the A380 while using up to 17% shorter runways.[27] In order to counter the perceived strength of the 747-8I, from 2012 Airbus will offer, as an option, improved maximum take-off weight allowing for a better payload/range performance. The precise size of the increase in maximum take-off weight is still unknown. British Airways and Emirates will be the first customers to take this offer.[28] As of April 2009 no airline has canceled an order for the passenger version of the A380. Boeing currently has only three commercial airline orders for the 747-8I: Lufthansa (20), Korean Airlines (5) and Arik Air (2).[29]

EADS A330 MRTT - Northrop Grumman KC-45A vs Boeing KC-767

Data are preliminary and partially copied from A330-200 and 767-200ER.

| A330 MRTT - KC-45 | KC-767 Advanced Tanker | |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 59.69 m | 48.5 m |

| Height | 16.9 m | 15.8 m |

| Fuselage Width | 5.64 m | 5.03 m |

| Wingspan | 60.3 m | 47.57 m |

| Surface area | 361.6 m² | |

| Engines | 2x RR Trent 700 or GE CF6-80 turbofans |

2x Pratt & Whitney PW4062 |

| Thrust (× 2) | 316 kN | 282 kN |

| Passengers | 226 - 280[30] | 190 |

| Range | 12,500 km | 12,200 km |

| Cruise speed | 860 km/h | Mach 0.80 (851 km/h) |

| Max speed | Mach 0.86 (915 km/h) | Mach 0.86 (915 km/h) |

| Max takeoff weight | 230 t | 181 t |

| Max landing weight | 180 t | 136 t |

| Normal fuel load | 250,000 lb (113,500 kg) | 161,000 lb (73,100 kg) |

| Maximum fuel load | 250,000 lb (113,500 kg) plus 95,800 lb (43,500 kg) of additional cargo or fuel load |

over 202,000 lb (91,600 kg) |

| Cargo (standard pallets) | 32 (463L) pallets | 19 (463L) pallets |

The announcement in March 2008 that Boeing had lost a US$40 billion refuelling aircraft contract to Northrop Grumman and Airbus for the EADS/Northrop Grumman KC-45 with the United States Air Force drew angry protests in the United States Congress.[31] Upon review of Boeing's protest, the Government Accountability Office ruled in favor of Boeing and ordered the USAF to recompete the contract. Later, the entire call for aircraft was rescheduled, then canceled, with a new call decided upon in March 2010.

Boeing later won the contest, with a lower price, on February 24, 2011.[32] The price was so low some in the media believe Boeing would take a loss on the deal; they also speculated that the company could perhaps break even with maintenance and spare parts contracts.[33] In July 2011, it was revealed that projected development costs rose $1.4bn and will exceed the $4.9bn contract cap by $300m. For the first $1bn increase (from the award price to the cap), the U.S. government would be responsible for $600m under a 60/40 government/Boeing split. With Boeing being wholly responsible for the additional $300m ceiling breach, Boeing would be responsible for a total of $700m of the additional cost.[34][35][36][clarification needed]

Competition and comparison

Competition by outsourcing

Because many of the world’s airlines are wholly or partially government owned, aircraft procurement decisions are often taken according to political and commercial criteria. Boeing and Airbus seek to exploit this by subcontracting production of aircraft components or assemblies to manufacturers in countries of strategic importance in order to gain a competitive advantage.

For example, Boeing has offered longstanding relationships with Japanese suppliers including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industries by which these companies have had increasing involvement on successive Boeing jet programs, a process which has helped Boeing achieve almost total dominance of the Japanese market for commercial jets. Outsourcing was extended on the 787 to the extent that Boeing’s own involvement was reduced to little more than project management, design, assembly and test operation, outsourcing most of the actual manufacturing all around the world. Boeing has since stated that it "outsourced too much" and that future airplane projects will depend far more on Boeing's own engineering and production personnel.[37]

Partly because of its origins as a consortium of European companies, Airbus has had fewer opportunities to outsource significant parts of its production beyond its own European plants. However, in 2009 Airbus has opened an assembly plant in Tianjin, China for production of its A320 series airliners.[38]

Competition through use of technology

Airbus sought to compete with the well-established Boeing in the 1970s through its introduction of advanced technology. For example, the A300 made the most extensive use of composite materials yet seen in an aircraft of that era, and by automating the flight engineer's functions, was the first large commercial jet to have a two-man flight crew. In the 1980s Airbus was the first to introduce digital Fly-by-wire controls into an airliner (the A320).

Since then Airbus has established itself as a viable competitor to Boeing, both companies use advanced technology to seek performance advantages in their products. For example, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is the first large airliner to use composites for most of its construction.

Competition through provision of engine choices

The competitive strength in the market of any airliner is considerably influenced by the choice(s) of engine available. In general, airlines prefer to have a choice of at least two engines from the major manufacturers General Electric, Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney. However engine manufacturers prefer to be single source, and often succeed in striking commercial deals with Boeing and Airbus to achieve their objective. Several notable aircraft have only provided a single engine offering: the Boeing 737-300 series onwards (CFM56), the Airbus A340-500 & 600 (Rolls-Royce Trent 500), the Airbus A350 (Rolls-Royce Trent XWB - so far) the Boeing 747-8 (GEnx-2B67), and the Boeing 777-300ER/200LR/F (General Electric GE90).[39]

Effect of currency on competition

Boeing's production costs are mostly in United States dollars, while Airbus' production costs are mostly in euros. When the dollar appreciates against the euro the cost of producing a Boeing aircraft rises relative to the cost of producing an Airbus aircraft, and conversely when the dollar falls relative to the euro it is an advantage for Boeing. There are also possible currency risks and benefits involved in the way aircraft are sold. Boeing typically prices its aircraft only in dollars, while Airbus, although pricing most aircraft sales in dollars, has been known to be more flexible and has priced some aircraft sales in Asia and the Middle East in multiple currencies. Depending on currency fluctuations between the acceptance of the order and the delivery of the aircraft this can result in an extra profit or extra expense - assuming Airbus has not purchased insurance against such fluctuations.[40]

Effect of competition on product plans

The A320 has been selected by 222 operators (Dec. 2008), among these several low-cost operators, gaining ground against the previously well established 737 in this sector; many full-service airlines also have selected it as a replacement for 727s and aging 737s, such as United Airlines and Lufthansa; and after 40 years the A380 now challenges the Boeing 747s dominance of the very large aircraft market. The Boeing 747-8 is a stretched and updated version of the venerable 747-400 and will offer greater capacity, fuel efficiency and longer range. Frequent delays to the Airbus A380 program caused several customers to consider cancelling their orders in favour of the refreshed 747-8,[41] although none have done so and some have even placed repeat orders for the A380. However, all A380F orders have been cancelled. To date, Boeing has secured orders for 78 747-8F and 28 747-8I with first deliveries originally scheduled for 2010 and 2011 respectively now, after certification the 747-8F, revised to 2011 and 2012 as the 747-8I is still (as of August 2011) being test-flown, while Airbus has orders for 234 A380s, the first of which entered service in 2007 and has delivered a total of 67 to customers (as of January 2012).

Several Boeing projects were pursued and then canceled, like the Sonic Cruiser, launched in 2001. Boeing is now focused on the Boeing 787 Dreamliner as a platform of total fleet rejuvenation, which uses technology from the Sonic Cruiser concept. The 787's rapid sales success and pressure from potential customers forced Airbus to revise the design of its competing A350.

Boeing first ruled out producing a re-engined version of its 737 to compete with the A320neo launch in 2016 saying it did not believe airlines would be willing to pay 10% more for only a few percentage gained in fuel efficiency, instead airlines would be looking towards the next major redesign and a 30% fuel saving. The company is facing airline pressure to offer a direct re-engined competitor including from Southwest Airlines who use the 737 for their entire fleet (680 in service or on order) saying they were not prepared to wait 20 years or more for a new 737 model and threatening to convert to Airbus. Industry sources believe that a re-engine of the 737 would be considerably more expensive for Boeing than it was for Airbus A320 due to the 737's design. Boeing eventually bowed to pressure in the summer of 2011 agreeing to supply a large quantity of a new version called the 737 MAX for one customer and the following quarter made the new product available to other customers.[42]

Safety

Both aircraft manufacturers have good safety records on recently manufactured aircraft. By convention, both companies tend to avoid safety comparisons when selling their aircraft to airlines. Most aircraft dominating the companies' aircraft sales, such as the Boeing 737-NG and Airbus A320 families (as well as both companies' wide-body offerings) have good safety records as well. Older model aircraft such as the Boeing 727, the original Boeing 737s and 747s, Airbus A300 and Airbus A310, which were respectively first flown during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, have had higher rates of fatal accidents.[43]

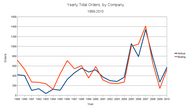

Orders and deliveries

| 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | |

| 270 | 1419 | 574 | 271 | 777 | 1341 | 790 | 1055 | 370 | 284 | 300 | 375 | 520 | 476 | 556 | 460 | 326 | 106 | 125 | 38 | 136 | 101 | 404 | 421 | |

| 700 | 805 | 530 | 142 | 662 | 1413 | 1044 | 1002 | 272 | 239 | 251 | 314 | 588 | 355 | 606 | 543 | 708 | 441 | 125 | 236 | 266 | 273 | 533 | 716 | |

| Sources 2012: Airbus net orders until July 31 2012 <http://www.airbus.com/company/market/orders-deliveries/>[44] Boeing net orders until July 31 2012 <http://active.boeing.com/commercial/orders/index.cfm> | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | |

| 326 | 534 | 510 | 498 | 483 | 453 | 434 | 378 | 320 | 305 | 303 | 325 | 311 | 294 | 229 | 182 | 126 | 124 | 123 | 138 | 157 | 163 | 95 | 105 | |

| 332 | 477 | 462 | 481 | 375 | 441 | 398 | 290 | 285 | 281 | 381 | 527 | 491 | 620 | 563 | 375 | 271 | 256 | 312 | 409 | 572 | 606 | 527 | 402 | |

| Sources 2011: Airbus deliveries until July 31 2012 <http://www.airbus.com/company/market/orders-deliveries/>[44] Boeing deliveries until July 31 2012 <http://active.boeing.com/commercial/orders/index.cfm?content=displaystandardreport.cfm&optReportType=CurYrDelv> | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Yearly orders.

-

Yearly deliveries.

-

Orders/Deliveries overlay.

Orders and deliveries, by product

| Civil airplanes | 2011 Deliveries | 2011 Orders | 2011 Backlog | Historical Deliveries * | Active airplanes ** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| single aisle | 1010 707 | 10 707 | ||||||||

| single aisle | 155 717 | 134 717 | ||||||||

| single aisle | 1831 727 | 82 727 | ||||||||

| single aisle | 421 A320 | 372 737 | 1348 A320 | 551 737 | 3345 A320 family | 2365 737 | 4947 A320 | 7010 737 | 4881 A320 | 5678 737 |

| single aisle | 1049 757 | 915 757 | ||||||||

| widebody | 20 767 | 42 767 | 72 767 | 561 A300 255 A310 |

1014 767 | 288 A300 140 A310 |

867 767 | |||

| widebody | 87 A330 | 73 777 | 85 A330 -2 A340 |

200 777 | 349 A330 2 A340 |

380 777 | 837 A330 375 A340 |

983 777 | 852 A330 335 A340 |

1011 777 |

| widebody | 0 A350 | 3 787 | -31 A350 | 13 787 | 555 A350 | 857 787 | 0 A350 | 3 787 | 15 787 | |

| widebody | 26 A380 | 9 747 | 19 A380 | -1 747 | 186 A380 | 97 747 | 67 A380 | 1427 747 | 80 A380 | 774 747 |

| Total | 534 | 477 | 1419 | 805 | 4437 | 3771 | 7042 | 14482 | 6576 | 9486 |

| *Historical deliveries are all Boeing since 1957 and all Airbus since 1972 until 31 December, 2011 | ||||||||||

| **Registered as active on airfleets.net as of june 2012 | ||||||||||

Sources : Wikipedia pages and Analysis: Airbus’s late push sees off Boeing - again

Orders by Decade

| Company/Decade | 2010s | 2000s | 1990s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 6083 | 2728 | |

| 1335 | 5927 | 4086 |

Deliveries by Decade

| Company/Decade | 2010s | 2000s | 1990s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1044 | 3810 | 1631 | |

| 939 | 3950 | 4511 |

Controversies

Subsidies

Boeing has continually protested over launch aid in the form of credits to Airbus, while Airbus has argued that Boeing receives illegal subsidies through military and research contracts and tax breaks.[45]

In July 2004 Harry Stonecipher (then-Boeing CEO) accused Airbus of abusing a 1992 bilateral EU-US agreement providing for disciplines for large civil aircraft support from governments. Airbus is given reimbursable launch investment (RLI, called "launch aid" by the US) from European governments with the money being paid back with interest, plus indefinite royalties if the aircraft is a commercial success.[46] Airbus contends that this system is fully compliant with the 1992 agreement and WTO rules. The agreement allows up to 33 per cent of the programme cost to be met through government loans which are to be fully repaid within 17 years with interest and royalties. These loans are held at a minimum interest rate equal to the cost of government borrowing plus 0.25%, which would be below market rates available to Airbus without government support.[47] Airbus claims that since the signing of the EU-U.S. agreement in 1992, it has repaid European governments more than U.S.$6.7 billion and that this is 40% more than it has received.

Airbus argues that the pork barrel military contracts awarded to Boeing (the second largest U.S. defense contractor) are in effect a form of subsidy (see the Boeing KC-767 vs EADS (Airbus) KC-45 military contracting controversy). The significant U.S. government support of technology development via NASA also provides significant support to Boeing, as does the large tax breaks offered to Boeing which some claim are in violation of the 1992 agreement and WTO rules. In its recent products such as the 787, Boeing has also been offered substantial support from local and state governments.[48] However, Airbus' parent, EADS, itself is a military contractor, and is paid to develop and build projects such as the Airbus A400M transport and various other military aircraft.[49]

In January 2005, the European Union and United States trade representatives, Peter Mandelson and Robert Zoellick (since replaced by Rob Portman, and then Susan Schwab, and the present office holder, Ron Kirk) respectively, agreed to talks aimed at resolving the increasing tensions. These talks were not successful with the dispute becoming more acrimonious rather than approaching a settlement.

In September 2009, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal reported that the World Trade Organization would likely rule against Airbus on most, but not all, of Boeing's complaints; the practical effect of this ruling would likely be blunted by the large number of international partners engaged by both plane makers, as well as the expected delay of several years of appeals. For example, 35% of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is manufactured in Japan. Thus, some experts are advocating a negotiated settlement.[50] In addition, the heavy government subsidies offered to automobile manufacturers in the United States have changed the political environment; the subsidies offered to Chrysler and General Motors dwarf the amounts involved in the Airbus-Boeing dispute.[51]

World Trade Organization litigation

"We remain united in our determination that this dispute shall not affect our cooperation on wider bilateral and multilateral trade issues. We have worked together well so far, and intend to continue to do so."

On 31 May 2005 the United States filed a case against the European Union for providing allegedly illegal subsidies to Airbus. Twenty-four hours later the European Union filed a complaint against the United States protesting support for Boeing.[53]

Increased tensions, due to the support for the Airbus A380, escalated toward a potential trade war as the launch of the Airbus A350 neared. Airbus would prefer the A350 programme to be launched with the help of state loans covering a third of the development costs although it has stated it will launch without these loans if required. The A350 will compete with Boeing's most successful project in recent years, the 787 Dreamliner. EU trade officials questioned the nature of the funding provided by NASA, the Department of Defense, and in particular the form of R&D contracts that benefit Boeing; as well as funding from US states such as the State of Washington, Kansas, and Illinois, for the development and launch of Boeing aircraft, in particular the 787.[54] An interim report of the WTO investigation into the claims made by both sides was made in September 2009.[55]

In March 2010, the WTO ruled that European governments unfairly financed Airbus.[56] In September 2010, a preliminary report of the WTO found unfair Boeing payments broke WTO rules and should be withdrawn.[57] In two separate findings issued in May 2011, the WTO found, firstly, that the US defense budget and NASA research grants could not be used as vehicles to subsidise the civilian aerospace industry and that Boeing must repay $5.3 billion of illegal subsidies.[58] Secondly, the WTO Appellate Body partly overturned an earlier ruling that European Governments launch aid constituted unfair subsidy, agreeing with the point of principle that the support was not aimed at boosting exports and some forms of public-private partnership could continue. Part of the $18bn in low interest loans received would have to be repaid eventually; however, there was no immediate need for it to be repaid and the exact value to be repaid would be set at a future date.[59] Both parties claimed victory in what is the world's largest trade dispute.[60][61][62]

On the first of December 2011 Airbus reported that it had fulfilled its obligations created by the WTO findings and called upon Boeing to do likewise in the coming year.[63] The United States did not agree and had already begun complaint procedures prior to December, stating the EU had failed to comply with the DSB's recommendations and rulings, it requested authorization by the DSB to take countermeasures under Article 22 of the DSU and Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union requested the matter be referred to arbitration under Article 22.6 of the DSU. The DSB agreed that the matter raised by the European Union in its statement at that meeting was referred to arbitration as required by Article 22.6 of the DSU however on 19 January 2012 the US and EU jointly agreed to withdraw their request for arbitration. [64]

On the 12 March 2012 the appellate body of the WTO released its findings confirming the illegality of subsidies to Boeing whilst confirming the legality of repayable loans made to Airbus. The WTO stated that Boeing had received at least $5.3 billion in illegal cash subsidies at an estimated cost to Airbus of $45 billion. A further $2 billion in state and local subsidies that Boeing is set to receive have also been declared illegal. Boeing and the US government have six months to change the way government support for Boeing is handled. [65] At the DSB meeting on 13 April 2012, the United States informed the DSB that it intended to implement the DSB recommendations and rulings in a manner that respects its WTO obligations and within the time-frame established in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union welcomed the US intention and noted that the 6-month period stipulated in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement would expire on 23 September 2012. On 24 April 2012, the European Union and the United States informed the DSB of Agreed Procedures under Articles 21 and 22 of the DSU and Article 7 of the SCM Agreement. [66]

See also

References

- ^ Airlines Industry Profile: United States, Datamonitor, November 2008, pp. 13–14

- ^ Airbus A320 Characteristics Airbus

- ^ Airbus.com: TECHNICAL BACKGROUNDER A330-200

- ^ "Boeing dévoile les formes définitives de son 787 Dreamliner". Marocinfocom.com. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Airbus's A350 vision takes shape Flight international

- ^ 19 May 2011. "Airbus product comparisons". Airbus.com. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Airbus goes for extra width - A350 XWB special report. Flight international

- ^ Boeing 777 Technical Specification. www.boeing.com

- ^ "Boeing 787-10ER Technical Specification". Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ a b Boeing admits 787-10 could face pressure. Flight international

- ^ 19 May 2011. "A350 Specifications". Airbus.com. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Factsheet Boeing 777-200[dead link]

- ^ Factsheet Boeing 777-300[dead link]

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ 19 May 2011. "A380 specifications". Airbus. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "747-400 specifications". Boeing. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "747-400ER specifications". Boeing. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "747-8 specifications". Boeing. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "Slide 1" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (20 December 2005). "A380 powers on through flight-test". Flight International. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Robertson, David. "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays", Time, 3 October 2006.

- ^ Schwartz, Nelson D. "Big plane, big problems", CNN, 1 March 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 747-8 Family background". Boeing.com. 2005-11-14. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "A380 family presskit". 2012-01-01. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ "British Airways and Emirates will be first for new longer-range A380". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "Korean 747-8I order snaps jumbo dry spell". Flightglobal.com. 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems - KC-45 Tanker[dead link]

- ^ "Air tanker deal provokes US row, BBC, 1 March 2008". BBC News. 2008-03-01. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "The USAF's KC-X Aerial Tanker RFP: Canceled". Defense Industry Daily. 13 March 2011.

- ^ Leeham News and Comment: How will Boeing profit from tanker contract?, 12-7-2011, visited: 3-2-2012

- ^ Broken link: [5], missing 3-2-2012

- ^ A1 Blog: Mc Cain blasts Boeing overruns

- ^ Defensenews.com: Boeing Lowers KC-46 Cost Estimate, 27-7-2011, visited: 3-2-2012

- ^ Gates, Dominic (March 1, 2010). "Albaugh: Boeing's 'first preference' is to build planes in Puget Sound region". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ "Airbus' China gamble". Flight International. October 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ^ Thomas, Geoffrey (April 4, 2008). "Engines the thrust of the Boeing-Airbus battle". The Australian. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Strong Euro Weighs on Airbus, Suppliers, Wall Street Journal, October 30, 2009, p.B3

- ^ Robertson, David (October 4, 2006). "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays". London: The Times Business News.

- ^ Associated, The (2011-01-20). "Southwest waiting to hear Boeing's plan for 737". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "No Slide Title" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ a b Airbus orders/deliveries Excel worksheet, per: 31-07-2012, downloaded: 6-8-2012

- ^ "Don't Let Boeing Close The Door On Competition" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Oconnell, Dominic; Porter, Andrew (2005-05-29). "Trade war threatened over £379m subsidy for Airbus". The Times. London. Retrieved Insert accessdate here.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Q&A: Boeing and Airbus". BBC News. 2004-10-07. Retrieved Insert accessdate here.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "See you in court". The Economist. 23 March 2005.

- ^ "EADS Military Air Systems Website, retrieved September 3, 2009". Eads.net. 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Clark, Nicola (2009-09-03). "W.T.O. to Weigh In on E.U. Subsidies for Airbus, New York Times, September 3, 2009, retrieved September 3, 2009". Europe;United States: Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Boeing Set for Victory Over Airbus in Illegal Subsidy Case, Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2009, p.A1

- ^ "EU, US face off at WTO in aircraft spat". Defense Aerospace. 31 May 2005.

- ^ "Flare-up in EU-US air trade row". BBC News. 31 May 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Milmo, Dan (14 August 2009). "US accuse Britain of stoking trade row with £340m Airbus loan". London: The Guardian.

- ^ "US refuses to disclose WTO ruling on Boeing-Airbus row". EU Business. 5 September 2009.

- ^ "WTO says Europe subsidizes Airbus, Boeing's rival, unfairly". USA Today. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ "EU claims victory in WTO case versus Boeing". Paris: Reuters. 15 September 2010.

- ^ Freedman, Jennifer M. "WTO Says U.S. Gave at Least $5.3 Billion Illegal Aid to Boeing". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "BBC News - WTO Airbus ruling leaves both sides claiming victory". Bbc.co.uk. 2011-04-19. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Lewis, Barbara (2011-05-19). "WTO gives mixed verdict on Airbus appeal". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "WTO final ruling: Decisive victory for Europe". LogisticsWeek. 2011-03-25. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ Khimm, Suzy (2011-05-17). "U.S. claims victory in Airbus-Boeing case". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ "Airbus satisfy WTO obligations".

- ^ "European Communities — Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft".

- ^ http://www.airbus.com/presscentre/pressreleases/press-release-detail/detail/sweeping-loss-for-boeing-in-wto-appeal/

- ^ "United States — Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft — Second Complaint".

- Bibliography

- Newhouse, John (2007), Boeng versus Airbus, USA: Vintage Books, ISBN 978-1-4000-7872-1