Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter | |

|---|---|

| |

| 39th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 | |

| Vice President | Walter Mondale |

| Preceded by | Gerald Ford |

| Succeeded by | Ronald Reagan |

| Governor of Georgia | |

| In office January 12, 1971 – January 14, 1975 | |

| Lieutenant | Lester Maddox |

| Preceded by | Lester Maddox |

| Succeeded by | George Busbee |

| Member of the Georgia Senate from the 14th district | |

| In office January 14, 1963 – January 10, 1967 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Carter |

| Constituency | Sumter County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1, 1924 Plains, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Rosalynn Smith (1946–present) |

| Children | Jack James Donnel Amy |

| Alma mater | Georgia Southwestern State University Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta United States Naval Academy |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1946–1953 |

| Rank | |

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States (1977–1981) and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office. Before he became President, Carter served as a U.S. Naval officer, was a peanut farmer, served two terms as a Georgia State Senator and one as Governor of Georgia (1971–1975).[2]

During Carter's term as President, two new cabinet-level departments were created: the Department of Energy and the Department of Education. He established a national energy policy that included conservation, price control, and new technology. In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties, the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II), and returned the Panama Canal Zone to Panama. He took office during a period of international stagflation, which persisted throughout his term. The end of his presidential tenure was marked by the 1979–1981 Iran hostage crisis, the 1979 energy crisis, the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, United States boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (the only U.S. boycott in Olympic history), and the eruption of Mount St. Helens.

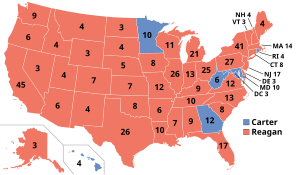

By 1980, Carter's popularity had eroded. He survived a primary challenge against Ted Kennedy for the Democratic Party nomination in the 1980 election, but lost the election to Republican candidate Ronald Reagan. On January 20, 1981, minutes after Carter's term in office ended, the 52 U.S. captives held at the U.S. embassy in Iran were released, ending the 444-day Iran hostage crisis.[3]

After leaving office, Carter and his wife Rosalynn founded the Carter Center in 1982,[4] a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization that works to advance human rights. He has traveled extensively to conduct peace negotiations, observe elections, and advance disease prevention and eradication in developing nations. Carter is a key figure in the Habitat for Humanity project,[5] and also remains particularly vocal on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Early life

James Earl Carter, Jr., was born at the Wise Sanitarium[6] on October 1, 1924, in the tiny southwest Georgia city of Plains, near Americus. The first president born in a hospital,[7] he is the eldest of four children of James Earl Carter and Bessie Lillian Gordy. Carter's father was a prominent business owner in the community and his mother was a registered nurse.

Carter is descended from immigrants from southern England (one of his paternal ancestors arrived in the American Colonies in 1635),[8] and his family has lived in the state of Georgia for several generations. Carter has documented ancestors who fought in the American Revolution, and he is a member of the Sons of the American Revolution.[9] Carter's great-grandfather, Private L.B. Walker Carter (1832–1874), served in the Confederate States Army.[10]

Carter was a gifted student from an early age who always had a fondness for reading. By the time he attended Plains High School, he was also a star in basketball. He was greatly influenced by one of his high school teachers, Julia Coleman (1889–1973). While he was in high school he was in the Future Farmers of America, which later changed its name to the National FFA Organization, serving as the Plains FFA Chapter Secretary.[11]

Carter had three younger siblings: sisters Gloria Carter Spann (1926–1990) and Ruth Carter Stapleton (1929–1983), and brother William Alton "Billy" Carter (1937–1988). During Carter's Presidency, Billy was often in the news, usually in an unflattering light.[12]

He married Rosalynn Smith in 1946; they have four children.

He is a first cousin of politician Hugh Carter and a half-second cousin of Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. on his mother's side, and a cousin of June Carter Cash.[13]

Naval career

After high school, Carter enrolled at Georgia Southwestern College, in Americus. Later, he applied to the United States Naval Academy and, after taking additional mathematics courses at Georgia Tech, he was admitted in 1943. Carter graduated 59th out of 820 midshipmen at the Naval Academy with a Bachelor of Science degree with an unspecified major, as was the custom at the academy at that time.[14]

Carter served on surface ships and on diesel-electric submarines in the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. As a junior officer, he completed qualification for command of a diesel-electric submarine. He applied for the US Navy's fledgling nuclear submarine program run by then Captain Hyman G. Rickover. Rickover's demands on his men and machines were legendary, and Carter later said that, next to his parents, Rickover had the greatest influence on him. Carter has said that he loved the Navy, and had planned to make it his career. His ultimate goal was to become Chief of Naval Operations. Carter felt the best route for promotion was with submarine duty since he felt that nuclear power would be increasingly used in submarines. Carter was based in Schenectady, New York, and working on developing training materials for the nuclear propulsion system for the prototype of a new submarine.[15]

On December 12, 1952, an accident with the experimental NRX reactor at Atomic Energy of Canada's Chalk River Laboratories caused a partial meltdown. The resulting explosion caused millions of liters of radioactive water to flood the reactor building's basement, and the reactor's core was no longer usable.[16] Carter was now ordered to Chalk River, joining other American and Canadian service personnel. He was the officer in charge of the U.S. team assisting in the shutdown of the Chalk River Nuclear Reactor.[17]

Once they arrived, Carter's team used a model of the reactor to practice the steps necessary to disassemble the reactor and seal it off. During execution of the actual disassembly each team member, including Carter, donned protective gear, was lowered individually into the reactor, stayed for only a few seconds at a time to minimize exposure to radiation, and used hand tools to loosen bolts, remove nuts and take the other steps necessary to complete the disassembly process.

During and after his presidency Carter indicated that his experience at Chalk River shaped his views on nuclear power and nuclear weapons, including his decision not to pursue completion of the neutron bomb.[18]

Upon the death of his father James Earl Carter, Sr., in July 1953, he was urgently needed to run the family business. Lieutenant Carter resigned his commission, and he was discharged from the Navy on October 9, 1953.

Farming and personal belief

Though Carter's father, Earl, died a relatively wealthy man, between Earl's forgiveness of debts owed to him and the division of his wealth among his heirs, Jimmy Carter inherited comparatively little. For a year, due to a limited real estate market, the Carters lived in public housing (Carter is the only U.S. president to have lived in housing subsidized for the poor).[19]

Knowledgeable in scientific and technological subjects and raised on a farm, Carter took over the family peanut farm. Carter took to the county library to read up on agriculture while Rosalynn learned accounting to manage the businesses financials.[19] Though they barely broke even the first year, Carter managed to expand in Plains. His farming business was successful, and during the 1970 gubernatorial campaign, he was considered a wealthy peanut farmer.[20]

From a young age, Carter showed a deep commitment to Christianity, serving as a Sunday School teacher throughout his life. Even as President, Carter prayed several times a day, and professed that Jesus Christ was the driving force in his life. Carter had been greatly influenced by a sermon he had heard as a young man, called, "If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?"[21]

Early political career

Georgia State Senate

Jimmy Carter started his political career by serving on various local boards, governing such entities as the schools, hospitals, and libraries, among others. In the 1960s, he served two terms in the Georgia Senate from the fourteenth district of Georgia.

His 1961 election to the state Senate, which followed the end of Georgia's County Unit System (per the Supreme Court case of Gray v. Sanders), was chronicled in his book Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age. The election involved corruption led by Joe Hurst, the sheriff of Quitman County; system abuses included votes from deceased persons and tallies filled with people who supposedly voted in alphabetical order. It took a challenge of the fraudulent results for Carter to win the election. Carter was reelected in 1964, to serve a second two-year term.

For a time in State Senate he chaired its Education Committee.[22]

In 1966, Carter declined running for re-election as a state senator to pursue a gubernatorial run. His first cousin, Hugh Carter, was elected as a Democrat and took over his seat in the Senate.

Campaigns for Governor

In 1966, during the end of his career as a state senator, he flirted with the idea of running for the United States House of Representatives. His Republican opponent, Howard Callaway, dropped out and decided to run for Governor of Georgia. Carter did not want to see a Republican Governor of his state, and, in turn, dropped out of the race for Congress and joined the race to become Governor. Carter lost the Democratic primary, but drew enough votes as a third-place candidate to force the favorite, liberal former governor Ellis Arnall, into a runoff election, setting off a chain of events which resulted in the nomination of segregationist Democrat Lester Maddox. Maddox would go on to be selected governor of Georgia by the Georgia General Assembly despite finishing a close second in a three-way general election race between Maddox, Callaway, and Arnall, who ran as a Write-in candidate. During the primary Carter ran as a moderate alternative to both liberal Arnall and conservative Maddox.[22] Although he lost, his strong third place finish was viewed as a success for a little-known state senator.[22]

For the next four years, Carter returned to his agriculture business and carefully planned for his next campaign for Governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state.[citation needed]

During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill populist campaign in the Democratic primary against former Governor Carl Sanders, labeling his opponent "Cufflinks Carl". Carter was never a segregationist, and refused to join the segregationist White Citizens' Council, prompting a boycott of his peanut warehouse. His family was also one of only two that voted to admit blacks to the Plains Baptist Church.[23]

"Carter himself was not a segregationist in 1970. But he did say things that the segregationists wanted to hear. He was opposed to busing. He was in favor of private schools. He said that he would invite segregationist governor George Wallace to come to Georgia to give a speech.", according to historian E. Stanly Godbold.[citation needed]

Carter's campaign aides handed out a photograph of Sanders celebrating with black basketball players.[24][25] Following his close victory over Sanders in the primary, he was elected Governor over Republican Hal Suit.

After his election, Carter would make a statement that would displease the segregationists: "I've traveled the state more than any other person in history and I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. Never again should a black child be deprived of an equal right to health care, education, or the other privileges of society."[26]

Leroy Johnson, Georgia State Senator reflected: "We were extremely pleased. Many of the white segregationists were displeased. And I'm convinced that those people that supported him, would not have supported him if they had thought that he would have made that statement."[27]

Governor of Georgia

Carter was sworn in as the 76th Governor of Georgia on January 12, 1971, and held this post for one term, until January 14, 1975. Governors of Georgia were not allowed to succeed themselves at the time. His predecessor as Governor, Lester Maddox, became the Lieutenant Governor. Carter and Maddox found little common ground during their four years of service, often publicly feuding with each other.[28][29]

Civil rights politics

Carter declared in his inaugural speech that the time of racial segregation was over, and that racial discrimination had no place in the future of the state, the first statewide office holder in the Deep South to say this in public.[30] Afterwards, Carter appointed many African Americans to statewide boards and offices. He was often called one of the "New Southern Governors" – much more moderate than their predecessors, and supportive of racial desegregation and expanding African-Americans' rights.[citation needed]

Abortion

Although "personally opposed" to abortion, after the landmark US Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, 410 US 113 (1973) Carter supported legalized abortion.[31] He did not support increased federal funding for abortion services as president and was criticized by the American Civil Liberties Union for not doing enough to find alternatives.[32] In March 2012, during an interview on The Laura Ingraham Show, Carter expressed his view that the Democratic Party should be more pro-life. He explained how difficult it was for him, given his strong Christian beliefs, to uphold Roe v. Wade while he was president.[33]

State government reforms

Carter improved government efficiency by merging about 300 state agencies into 30 agencies. One of his aides recalled that Governor Carter "was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his." He also pushed reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.[34][35]

Vice-Presidential aspirations in 1972

In 1972, as US Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy, yet when McGovern's nomination became a foregone conclusion, Carter lobbied to become his vice-presidential running mate.

During the 1972 Democratic National Convention he endorsed the candidacy of Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington.[36] Carter received 30 votes at the Democratic National Convention in the chaotic ballot for Vice President.[citation needed] McGovern offered the second spot to Reubin Askew, from next door Florida and one of the "new southern governors", but he declined.[citation needed]

Death penalty and crime

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Georgia's death penalty law in 1972, Carter quickly proposed state legislation to replace the death penalty with life in prison without parole (an option that previously did not exist).[37]

When the Georgia legislature passed a new death penalty statute, Carter, despite voicing reservations about its constitutionality,[38] signed new legislation on March 28, 1973[39] to authorize the death penalty for murder, rape and other offenses, and to implement trial procedures that conformed to the newly announced constitutional requirements. In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Georgia's new death penalty for murder. In the case of Coker v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional as applied to rape.

Many in America were outraged by William Calley's life sentence at Fort Benning for his role in the My Lai Massacre; Carter instituted "American Fighting Man's Day" and asked Georgians to drive for a week with their lights on in support of Calley.[40] Indiana's governor asked all state flags to be flown at half-staff for Calley, and Utah's and Mississippi's governors also disagreed with the verdict.[40]

Despite his earlier support, Carter soon became a death penalty opponent, and during Presidential campaigns (like previous nominee George McGovern and two successive nominees, Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis), this was noted.[41] Carter is known for his outspoken opposition to the death penalty in all forms; in his Nobel Prize lecture, he urged "prohibition of the death penalty".[42]

United States Senate appointment

Richard Russell, Jr., then-President pro tempore of the United States Senate, died in office on January 21, 1971. Carter, only nine days into his governorship, appointed state Democratic Party chair David H. Gambrell to fill an unexpired Russell term in the Senate on February 1.[43] Gambrell was defeated in the next Democratic primary by the more conservative Sam Nunn.

Other activities

In 1973, while Governor of Georgia, Carter filed a report on his 1969 UFO sighting with the International UFO Bureau in Oklahoma City.[44][45][46] In 2007, Carter stated that he did not remember why he filed the report and that he believes he probably only did it at the request of one of his children. He also stated he does not believe it was an alien spacecraft, but rather that it was likely some sort of military experiment being conducted from a nearby military base.[47]

Carter made an appearance as the first guest of the evening on an episode of the game show What's My Line in 1974, signing in as "X", lest his name give away his occupation. After his job was identified on question seven of ten by Gene Shalit, he talked about having brought movie production to the state of Georgia, citing Deliverance, and the then-unreleased The Longest Yard.

In 1974, Carter was chairman of the Democratic National Committee's congressional, as well as gubernatorial, campaigns.

1976 presidential campaign

When Carter entered the Democratic Party presidential primaries in 1976, he was considered to have little chance against nationally better-known politicians. He had a name recognition of only two percent. When he told his family of his intention to run for President, his mother asked, "President of what?" The Watergate scandal was still fresh in the voters' minds, and so his position as an outsider, distant from Washington, D.C., became an asset. The centerpiece of his campaign platform was government reorganization. Carter published Why Not the Best? in June 1976 to help introduce himself to the American public.[48]

Carter became the front-runner early on by winning the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. He used a two-prong strategy: In the South, which most had tacitly conceded to Alabama's George Wallace, Carter ran as a moderate favorite son. When Wallace proved to be a spent force, Carter swept the region. In the North, Carter appealed largely to conservative Christian and rural voters and had little chance of winning a majority in most states. He won several Northern states by building the largest single bloc. Carter's strategy involved reaching a region before another candidate could extend influence there. He traveled over 50,000 miles, visited 37 states, and delivered over 200 speeches before any other candidates even announced that they were in the race.[49] Initially dismissed as a regional candidate, Carter proved to be the only Democrat with a truly national strategy, and he eventually clinched the nomination.

The national news media discovered and promoted Carter, as Lawrence Shoup noted in his 1980 book The Carter Presidency and Beyond:

What Carter had that his opponents did not was the acceptance and support of elite sectors of the mass communications media. It was their favorable coverage of Carter and his campaign that gave him an edge, propelling him rocket-like to the top of the opinion polls. This helped Carter win key primary election victories, enabling him to rise from an obscure public figure to President-elect in the short space of 9 months.

Carter was interviewed by Robert Scheer of Playboy for its November 1976 issue, which hit the newsstands a couple of weeks before the election. It was here that in the course of a digression on his religion's view of pride, Carter admitted: "I've looked on a lot of women with lust. I've committed adultery in my heart many times."[50] He remains the only American president to be interviewed by this magazine.

As late as January 26, 1976, Carter was the first choice of only four percent of Democratic voters, according to a Gallup poll. Yet "by mid-March 1976 Carter was not only far ahead of the active contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination, he also led President Ford by a few percentage points", according to Shoup.

He chose Senator Walter F. Mondale as his running mate. He attacked Washington in his speeches, and offered a religious salve for the nation's wounds.[51]

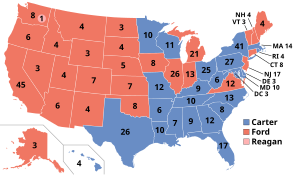

Carter began the race with a sizable lead over Ford, who was able to narrow the gap over the course of the campaign, but was unable to prevent Carter from narrowly defeating him on November 2, 1976. Carter won the popular vote by 50.1 percent to 48.0 percent for Ford and received 297 electoral votes to Ford's 240. The electoral vote was so close that if Ford had carried Texas and Arkansas (instead of Carter), Ford would have won the election. Carter became the first contender from the Deep South to be elected President since the 1848 election. Carter carried fewer states than Ford—23 states to the defeated Ford's 27—yet Carter won with the largest percentage of the popular vote (50.1 percent) of any non-incumbent since Dwight Eisenhower, and only half a percent less than what Ronald Reagan would defeat him with in 1980.

Presidency

Carter was elected over Gerald Ford in 1976. His tenure was a time of continuing inflation and recession, as well as an energy crisis. On January 7, 1980, Carter signed Law H.R. 5860 aka Public Law 96-185 known as The Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Act of 1979 bailing out Chrysler Corporation and canceled military pay raises during a time of high inflation and government deficits.

While attempting to calm various conflicts around the World, most visibly in the Middle East resulting in the signing of the Camp David Accords, giving back the Panama Canal and signing the SALT II nuclear arms reduction treaty with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, the final year of his administration was marred by the Iran hostage crisis, which contributed to his losing his 1980 re-election campaign to Ronald Reagan.

U.S. Energy Crisis

On April 18, 1977 Carter delivered a televised speech declaring that the U.S. energy crisis during the 1970s was the moral equivalent of war. Carter encouraged energy conservation by all U.S. citizens and installed solar water heating panels on the White House,[52][53] and wore sweaters while turning down the heat within the White House.

EPA Love Canal Superfund

In 1978, Carter declared a federal emergency in the neighborhood of Love Canal in the city of Niagara Falls, New York. More than 800 families were evacuated from the neighborhood, which was built on top of a toxic waste landfill. The Superfund law was created in response to the situation. Federal disaster money was appropriated to demolish the approximately 500 houses, the 99th Street School, and the 93rd Street School, which were built on top of the dump and to remediate the dump and construct a containment area. This was the first time that such a thing had been done. He then said that there were several more "Love Canals" across the country, and that discovering such dumpsites was "one of the grimmest discoveries of our modern era".

Deregulation

American beer industry

Airline Deregulation Act.

During 1979, Carter deregulated the American beer industry by opening access of the home-brew market back up to the craft brewers, making it again legal to sell malt, hops, and yeast to American home brewers for the first time since the effective 1920 beginning of Prohibition in the United States.[54]

U.S. Airline Industry

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed Alfred E. Kahn, a professor of economics at Cornell University, to be chair of the CAB. A concerted push for the legislation had developed, drawing on leading economists, leading 'think tanks' in Washington, a civil society coalition advocating the reform (patterned on a coalition earlier developed for the truck-and-rail-reform efforts), the head of the regulatory agency, Senate leadership, the Carter administration, and even some in the airline industry. This coalition swiftly gained legislative results in 1978.

The Airline Deregulation Act (Pub. L. 95–504) is United States enacted federal legislation signed into law by President Carter on October 24, 1978. The main purpose of the act was to remove government control over fares, routes and market entry (of new airlines) from commercial aviation. The Civil Aeronautics Board's powers of regulation were to be phased out, eventually allowing passengers to be exposed to market forces in the airline industry. The Act, however, did not remove or diminish the FAA's regulatory powers over all aspects of airline safety.

U.S. Boycott of the Moscow Olympics

One of Carter's most bitterly controversial decisions was his boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow in response to the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. This marks the only time since the founding of the modern Olympics in 1896 that the United States has ever failed to participate in a Summer or Winter Olympics. The Soviet Union retaliated by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles and did not withdraw troops from Afghanistan until 1989 (eight years after Carter left office).

1980 presidential campaign

Carter wrote that the most intense and mounting opposition to his policies came from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which he attributed to Ted Kennedy's ambition to replace him as president.[55] Kennedy, originally on board with Carter's health plan, pulled his support from that legislation in the late stages; Carter states that this was in anticipation of Kennedy's own candidacy, and when neither won, the tactic effectively delayed comprehensive health coverage for decades.[56]

Carter's campaign for re-election in 1980 was one of the most difficult, and least successful, in history. He faced strong challenges from the right (Ronald Reagan), the center (John B. Anderson), and the left (Ted Kennedy). He had to run against his own "stagflation"-ridden economy. He alienated liberal college students, who were expected to be his base, by re-instating registration for the draft. He was defeated by Ronald Reagan.

Post-Presidency

In 1981, Carter returned to Georgia to his peanut farm, which he had placed into a blind trust during his presidency to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest. He found that the trustees had mismanaged the trust, leaving him over one million dollars in debt. In the years that followed, he has led an active life, establishing The Carter Center, building his presidential library, teaching at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and writing numerous books.[51]

Legacy

When he first left office, Carter's presidency was viewed by most as a failure.[57][58][59] In historical rankings of US presidents, the Carter presidency has ranged from #19 to #34. Although Carter's presidency received mixed reviews from some historians, his all-around peace keeping and humanitarian efforts since he left office have led him to be renowned as one of the most successful ex-presidents in US history.[60][61]

Although Carter has also received mixed reviews in both television and film documentaries, such as the Man from Plains (2007), the 2009 documentary, Back Door Channels: The Price of Peace, credits Carter's efforts at Camp David, which brought peace between Israel and Egypt, with bringing the only meaningful peace to the Middle East. The film opened the 2009 Monte-Carlo Television Festival in an invitation-only royal screening[62] on June 7, 2009 at the Grimaldi Forum in the presence of Albert II, Prince of Monaco.[63]

Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale are the longest-living post-presidential team in American history. On December 11, 2006, they had been out of office for 25 years and 325 days, surpassing the former record established by President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson, who both died on July 4, 1826. On September 7, 2012, Carter is expected to surpass Herbert Hoover as the President with the longest retirement from the office.

Jimmy Carter is one of only four presidents, and the only one in modern history, who did not have an opportunity to nominate a justice to serve on the Supreme Court. The other three are William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Andrew Johnson. Of these four, Carter is the only to have served a full term.

Public image

The Independent writes, "Carter is widely considered a better man than he was a president."[64] While he began his term with a 66 percent approval rating,[65] this had dropped to 34 percent approval by the time he left office, with 55 percent disapproving.[66]

Much of this image in the public eye results from the Presidents proximate to him in history.[67] In the wake of Nixon's Watergate Scandal, exit polls from the 1976 Presidential election suggested that many still held Gerald Ford's pardon of Nixon against him,[68] and Carter by comparison seemed a sincere, honest, and well-meaning Southerner.[64]

Despite being honest and truthful, Carter's administration suffered from his inexperience in politics. Carter paid too much attention to detail. He frequently backed down from confrontation and was always quick to retreat when under fire from political rivals. He frequently appeared to be indecisive and ineffective, and did not define his priorities clearly. He seemed to be distrustful and uninterested in working with other groups, or even with Congress when controlled by his own party, which he denounced for being controlled by special interest groups.[67] Though he made efforts to address many of these issues in 1978, the approval he won from his reforms did not last long.

When Carter ran for reelection, Ronald Reagan's nonchalant self-confidence contrasted to Carter's serious and introspective temperament. Carter's personal attention to detail, his pessimistic attitude, his seeming indecisiveness and weakness with people was also accentuated by Reagan's charismic charm and easy delegation of tasks to subordinates.[67][69] Ultimately, the combination of the economic problems, the Iran hostage crisis, and lack of Washington cooperation made it very easy for Reagan to portray Carter as a weak and ineffectual leader, which resulted in Carter to become the first elected president since 1932 to lose a reelection bid, and his presidency was largely considered to be a failure.

Notwithstanding perceptions while Carter was in office, his reputation has much improved. Carter's presidential approval rating, which sat at 31 percent just prior to the 1980 election, was polled in early 2009 at 64 percent.[70] Carter's continued post-Presidency activities have also been favorably received. Carter explains that a great deal of this change was owed to Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, who actively sought him out and was far more courteous and interested in his advice than Reagan had been.[64]

Carter Center

As President, Carter expressed a goal of making government "competent and compassionate." In pursuit of that vision, he has been involved in a variety of national and international public policy, conflict resolution, human rights and charitable causes.

In 1982, he established The Carter Center in Atlanta to advance human rights and alleviate unnecessary human suffering. The non-profit, nongovernmental Center promotes democracy, mediates and prevents conflicts, and monitors the electoral process in support of free and fair elections. It also works to improve global health through the control and eradication of diseases such as Guinea worm disease, river blindness, malaria, trachoma, lymphatic filariasis, and schistosomiasis. It also works to diminish the stigma of mental illnesses and improve nutrition through increased crop production in Africa. A major accomplishment of The Carter Center has been the elimination of more than 99 percent of cases of Guinea worm disease, a debilitating parasite that has existed since ancient times, from an estimated 3.5 million cases in 1986 to 3,190 reported cases in 2009.[71] The Carter Center has monitored 81 elections in 33 countries since 1989.[72] It has worked to resolve conflicts in Haiti, Bosnia, Ethiopia, North Korea, Sudan and other countries. Carter and the Center actively support human rights defenders around the world and have intervened with heads of state on their behalf.

Nobel Peace Prize

In 2002, President Carter received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work "to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development" through The Carter Center.[73] Three sitting presidents, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and Barack Obama, have received the prize; Carter is unique in receiving the award for his actions after leaving the presidency. He is, along with Martin Luther King, Jr., one of only two native Georgians to receive the Nobel.

Diplomacy

North Korea

In 1994, North Korea had expelled investigators from the International Atomic Energy Agency and was threatening to begin processing spent nuclear fuel. In response, then-President Clinton pressured for US sanctions and ordered large amounts of troops and vehicles into the area to brace for war.

Bill Clinton secretly recruited Carter to undertake a peace mission to North Korea,[74] under the guise that it was a private mission of Carter's. Clinton saw Carter as a way to let North Korean President Kim Il-sung back down without losing face.[75]

Carter negotiated an understanding with Kim Il-sung, but went further and outlined a treaty, which he announced on CNN without the permission of the Clinton White House as a way to force the US into action. The Clinton Administration signed a later version of the Agreed Framework, under which North Korea agreed to freeze and ultimately dismantle its current nuclear program and comply with its nonproliferation obligations in exchange for oil deliveries, the construction of two light water reactors to replace its graphite reactors, and discussions for eventual diplomatic relations.

The agreement was widely hailed at the time as a significant diplomatic achievement.[76][77] In December 2002, the Agreed Framework collapsed as a result of a dispute between the George W. Bush Administration and the North Korean government of Kim Jong-il. In 2001, Bush had taken a confrontational position toward North Korea and, in January 2002, named it as part of an "Axis of Evil". Meanwhile, North Korea began developing the capability to enrich uranium. Bush Administration opponents of the Agreed Framework believed that the North Korean government never intended to give up a nuclear weapons program, but supporters believed that the agreement could have been successful and was undermined.[78]

In August 2010, Carter traveled to North Korea in an attempt to secure the release of Aijalon Mahli Gomes. Gomes, a U.S. citizen, was sentenced to eight years of hard labor after being found guilty of illegally entering North Korea. Carter successfully secured the release.[79]

Middle East

Carter and experts from The Carter Center assisted unofficial Israeli and Palestinian negotiators in designing a model agreement for peace–-called the Geneva Accord–-in 2002–2003.[80]

Carter has also in recent years become a frequent critic of Israel's policies in Lebanon, West Bank, and Gaza.[81][82]

In 2006, at the UK Hay Festival, Carter stated that Israel has at least 150 nuclear weapons. He expressed his support for Israel as a country, but criticized its domestic and foreign policy; "One of the greatest human rights crimes on earth is the starvation and imprisonment of 1.6m Palestinians," said Carter.

He mentioned statistics showing nutritional intake of some Palestinian children was below that of the children of Sub-Saharan Africa and described the European position on Israel as "supine".[83]

In April 2008, the London-based Arabic newspaper Al-Hayat reported that Carter met with exiled Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal on his visit to Syria. The Carter Center initially did not confirm nor deny the story. The US State Department considers Hamas a terrorist organization.[84] Within this Mid-East trip, Carter also laid a wreath on the grave of Yasser Arafat in Ramallah on April 14, 2008.[85] Carter said on April 23 that neither Condoleezza Rice nor anyone else in the State Department had warned him against meeting with Hamas leaders during his trip.[86] Carter spoke to Mashaal on several matters, including "formulas for prisoner exchange to obtain the release of Corporal Shalit."[87]

In May 2007, while arguing that the United States should directly talk to Iran, Carter again stated that Israel has 150 nuclear weapons in its arsenal.[88]

In December 2008, Carter visited Damascus again, where he met with Syrian President Bashar Assad, and the Hamas leadership. During his visit he gave an exclusive interview to Forward Magazine, the first ever interview for any American president, current or former, with a Syrian media outlet.[89][90]

Carter visited with three officials from Hamas who have been living at the International Red Cross office in Jerusalem since July 2010. Israel believes that these three Hamas legislators had a role in the 2006 kidnapping of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, and has a deportation order set for them.[91]

Africa

Carter held summits in Egypt and Tunisia in 1995–1996 to address violence in the Great Lakes region of Africa.[92]

Carter played a key role in negotiation of the Nairobi Agreement in 1999 between Sudan and Uganda.[93]

On July 18, 2007, Carter joined Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg, South Africa, to announce his participation in a new humanitarian organization called The Elders. In October 2007, Carter toured Darfur with several of The Elders, including Desmond Tutu. Sudanese security prevented him from visiting a Darfuri tribal leader, leading to a heated exchange.[94]

On June 18, 2007, Carter, accompanied by his wife, arrived in Dublin, Ireland, for talks with President Mary McAleese and Bertie Ahern concerning human rights. On June 19, Carter attended and spoke at the annual Human Rights Forum at Croke Park. An agreement between Irish Aid and The Carter Center was also signed on this day.

In November 2008, President Carter, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, and Graca Machel, wife of Nelson Mandela, were stopped from entering Zimbabwe, to inspect the human rights situation, by President Robert Mugabe's government.

Americas

Carter led a mission to Haiti in 1994 with Senator Sam Nunn and former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell to avert a US-led multinational invasion and restore to power Haiti's democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.[95]

Carter visited Cuba in May 2002 and had full discussions with Fidel Castro and the Cuban government. He was allowed to address the Cuban public uncensored on national television and radio with a speech that he wrote and presented in Spanish. In the speech, he called on the US to end "an ineffective 43-year-old economic embargo" and on Castro to hold free elections, improve human rights, and allow greater civil liberties.[96] He met with political dissidents; visited the AIDS sanitarium, a medical school, a biotech facility, an agricultural production cooperative, and a school for disabled children; and threw a pitch for an all-star baseball game in Havana. The visit made Carter the first President of the United States, in or out of office, to visit the island since the Cuban revolution of 1959.[97]

Carter observed the Venezuela recall elections on August 15, 2004. European Union observers had declined to participate, saying too many restrictions were put on them by the Hugo Chávez administration.[98] A record number of voters turned out to defeat the recall attempt with a 59 percent "no" vote.[99] The Carter Center stated that the process "suffered from numerous irregularities," but said it did not observe or receive "evidence of fraud that would have changed the outcome of the vote".[100] On the afternoon of August 16, 2004, the day after the vote, Carter and Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General César Gaviria gave a joint press conference in which they endorsed the preliminary results announced by the National Electoral Council. The monitors' findings "coincided with the partial returns announced today by the National Elections Council," said Carter, while Gaviria added that the OAS electoral observation mission's members had "found no element of fraud in the process." Directing his remarks at opposition figures who made claims of "widespread fraud" in the voting, Carter called on all Venezuelans to "accept the results and work together for the future".[101] A Penn, Schoen & Berland Associates (PSB) exit poll had predicted that Chávez would lose by 20 percent; when the election results showed him to have won by 20 percent, Schoen commented, "I think it was a massive fraud".[102] US News & World Report offered an analysis of the polls, indicating "very good reason to believe that the [Penn, Schoen & Berland] exit poll had the result right, and that Chávez's election officials – and Carter and the American media – got it wrong." The exit poll and the government's programming of election machines became the basis of claims of election fraud. An Associated Press report states that Penn, Schoen & Berland used volunteers from pro-recall organization Súmate for fieldwork, and its results contradicted five other opposition exit polls.[103]

Following Ecuador's severing of ties with Colombia in March 2008, Carter brokered a deal for agreement between the countries' respective presidents on the restoration of low-level diplomatic relations announced June 8, 2008.[104][105]

Vietnam

On November 18, 2009, Carter visited Vietnam to build houses for the poor. The one-week program, known as Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Work Project 2009, built 32 houses in Dong Xa village, in the northern province of Hai Duong. The project launch was scheduled for November 14, according to the news source which quoted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Nguyen Phuong Nga. Administered by the non-governmental and non-profit Habitat for Humanity International (HFHI), the annual program of 2009 would build and repair 166 homes in Vietnam and some other Asian countries with the support of nearly 3,000 volunteers around the world, the organization said on its website. HFHI has worked in Vietnam since 2001 to provide low-cost housing, water, and sanitation solutions for the poor. It has worked in provinces like Tien Giang and Dong Nai as well as Ho Chi Minh City.[106]

Criticism of US policy

In 2001, Carter criticized President Bill Clinton's controversial pardon of Marc Rich, calling it "disgraceful" and suggesting that Rich's financial contributions to the Democratic Party were a factor in Clinton's action.[107]

Carter has also criticized the presidency of George W. Bush and the Iraq War. In a 2003 op-ed in The New York Times, Carter warned against the consequences of a war in Iraq and urged restraint in use of military force.[108] In March 2004, Carter condemned George W. Bush and Tony Blair for waging an unnecessary war "based upon lies and misinterpretations" to oust Saddam Hussein. In August 2006, Carter criticized Blair for being "subservient" to the Bush administration and accused Blair of giving unquestioning support to Bush's Iraq policies.[109] In a May 2007 interview with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, he said, "I think as far as the adverse impact on the nation around the world, this administration has been the worst in history," when it comes to foreign affairs.[110][111] Two days after the quote was published, Carter told NBC's Today that the "worst in history" comment was "careless or misinterpreted," and that he "wasn't comparing this administration with other administrations back through history, but just with President Nixon's."[112] The day after the "worst in history" comment was published, White House spokesman Tony Fratto said that Carter had become "increasingly irrelevant with these kinds of comments."[113]

On May 19, 2007, Mr. Blair made his final visit to Iraq before stepping down as British Prime Minister, and Carter criticized him afterward. Carter told the BBC that Blair was "apparently subservient" to Bush and criticized him for his "blind support" for the Iraq war.[114] Carter described Blair's actions as "abominable" and stated that the British Prime Minister's "almost undeviating support for the ill-advised policies of President Bush in Iraq have been a major tragedy for the world." Carter said he believes that had Blair distanced himself from the Bush administration during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, it might have made a crucial difference to American political and public opinion, and consequently the invasion might not have gone ahead. Carter states that "one of the defenses of the Bush administration ... has been, okay, we must be more correct in our actions than the world thinks because Great Britain is backing us. So I think the combination of Bush and Blair giving their support to this tragedy in Iraq has strengthened the effort and has made the opposition less effective, and prolonged the war and increased the tragedy that has resulted." Carter expressed his hope that Blair's successor, Gordon Brown, would be "less enthusiastic" about Bush's Iraq policy.[114]

In June 2005, Carter urged the closing of the Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba, which has been a focal point for recent claims of prisoner abuse.[115]

In September 2006, Carter was interviewed on the BBC's current affairs program Newsnight, voicing his concern at the increasing influence of the Religious Right on US politics.[116]

Due to his status as former President, Carter was a superdelegate to the 2008 Democratic National Convention. Carter announced his endorsement of Senator (now president) Barack Obama.

Speaking to the English Monthly Forward magazine of Syria, Carter was asked to give one word that came to mind when mentioning President George W. Bush. His answer was: the end of a very disappointing administration. His reaction to mentioning Barack Obama was: honesty, intelligence, and politically adept.[117]

In September 2009, he put weight behind allegations by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, pertaining to United States involvement in the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt by a civilian-military junta, saying that Washington knew about the coup and may have taken part.[118]

On June 16, 2011, the 40th anniversary of Richard Nixon's official declaration of America's War on Drugs, he wrote an op-ed in The New York Times urging the United States and the rest of the world to "Call Off the Global War on Drugs",[119] explicitly endorsing the initiative released by the Global Commission on Drug Policy earlier that month and quoting a message he gave to Congress in 1977 saying that "[p]enalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself."

Death penalty

Carter continues to speak out against the death penalty in the US and abroad. Most recently, in his letter to the Governor of New Mexico, Bill Richardson, Carter urged him to sign a bill to eliminate the death penalty and institute life in prison without parole instead. New Mexico abolished the death penalty in 2009. Carter wrote: As you know, the United States is one of the few countries, along with nations such as Saudi Arabia, China, and Cuba, which still carry out the death penalty despite the ongoing tragedy of wrongful conviction and gross racial and class-based disparities that make impossible the fair implementation of this ultimate punishment.[120]

Carter also called for commutations of death sentences for many death-row inmates, including Brian K. Baldwin (executed in 1999 in Alabama),[121] Kenneth Foster (sentence in Texas commuted in 2007)[122][123] and Troy Anthony Davis (executed in Georgia in 2011).[124]

Torture

In a 2008 interview with Amnesty International, Carter criticized the alleged use of torture at Guantanamo Bay, saying that it "contravenes the basic principles on which this nation was founded."[125] He stated that the next President should publicly apologize upon his inauguration, and state that the United States will "never again torture prisoners."

Abortion

In a March 29, 2012 interview with Laura Ingraham, Carter expressed his current view of abortion and his wish to see the Democratic Party becoming more pro-life: "I never have believed that Jesus Christ would approve of abortions and that was one of the problems I had when I was president having to uphold Roe v. Wade and I did everything I could to minimize the need for abortions. I made it easy to adopt children for instance who were unwanted and also initiated the program called Women and Infant Children or WIC program that's still in existence now. But except for the times when a mother's life is in danger or when a pregnancy is caused by rape or incest I would certainly not or never have approved of any abortions. I've signed a public letter calling for the Democratic Party at the next convention to espouse my position on abortion which is to minimize the need, requirement for abortion and limit it only to women whose life [sic?] are in danger or who are pregnant as a result of rape or incest. I think if the Democratic Party would adopt that policy that would be acceptable to a lot of people who are now estranged from our party because of the abortion issue."[126]

Author

Carter has been a prolific author in his post-presidency, writing 21 of his 23 books. Among these is one he co-wrote with his wife, Rosalynn, and a children's book illustrated by his daughter, Amy. They cover a variety of topics, including humanitarian work, aging, religion, human rights, and poetry.

Palestine Peace Not Apartheid

In a 2007 speech to Brandeis University, Carter stated: "I have spent a great deal of my adult life trying to bring peace to Israel and its neighbors, based on justice and righteousness for the Palestinians. These are the underlying purposes of my new book."[127]

In his book Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, published in November 2006, Carter states:

Israel's continued control and colonization of Palestinian land have been the primary obstacles to a comprehensive peace agreement in the Holy Land.[128]

He declares that Israel's current policies in the Palestinian territories constitute "a system of apartheid, with two peoples occupying the same land, but completely separated from each other, with Israelis totally dominant and suppressing violence by depriving Palestinians of their basic human rights."[128] In an Op-Ed titled "Speaking Frankly about Israel and Palestine," published in the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers, Carter states:

The ultimate purpose of my book is to present facts about the Middle East that are largely unknown in America, to precipitate discussion and to help restart peace talks (now absent for six years) that can lead to permanent peace for Israel and its neighbors. Another hope is that Jews and other Americans who share this same goal might be motivated to express their views, even publicly, and perhaps in concert. I would be glad to help with that effort.[129]

While some – such as a former Special Rapporteur for both the United Nations Commission on Human Rights and the International Law Commission, as well as a member of the Israeli Knesset – have praised Carter for speaking frankly about Palestinians in Israeli occupied lands, others – including the envoy to the Middle East under Clinton, as well as the first director of the Carter Center[130][131] – have accused him of anti-Israeli bias. Specifically, these critics have alleged significant factual errors, omissions and misstatements in the book.[132][133]

The 2007 documentary film, Man from Plains, follows President Carter during his tour for the controversial book and other humanitarian efforts.[134]

In December 2009, Carter apologized for any words or deeds that may have upset the Jewish community in an open letter meant to improve an often tense relationship. He said he was offering an Al Het, a prayer said on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement.[135]

Involvement with Bank of Credit and Commerce International

After Carter left the presidency, his interest in the developing countries led him to having a close relationship with Agha Hasan Abedi, the founder of Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI). Abedi was a Pakistani, whose bank had offices and business in a large number of developing countries. He was introduced to Carter in 1982 by Bert Lance, one of Carter's closest friends. (Unknown to Carter, BCCI had secretly purchased an interest in 1978 in National Bank of Georgia, which had previously been run by Lance and had made loans to Carter's peanut business.) Abedi made generous donations to the Carter Center and the Global 2000 Project. Abedi also traveled with Carter to at least seven countries in connection with Carter's charitable activities. The main purpose of Abedi's association with Carter was not charitable activities, but to enhance BCCI's influence, in order to open more offices and develop more business. In 1991, BCCI was seized by regulators, amid allegations of criminal activities, including illegally having control of several U.S. banks. Just prior to the seizure, Carter began to disassociate himself from Abedi and the bank.[136]

Faith, family, and community

Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, are also well known for their work as volunteers with Habitat for Humanity, a Georgia-based philanthropy that helps low-income working people to build and buy their own homes.

He teaches Sunday school and is a deacon in the Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia, under the watchful eye of the U.S. Secret Service.[137] In 2000, Carter severed ties with the Southern Baptist Convention, saying the group's doctrines did not align with his Christian beliefs.[138] In April 2006, Carter, former-President Bill Clinton and Mercer University President Bill Underwood initiated the New Baptist Covenant. The broadly inclusive movement seeks to unite Baptists of all races, cultures and convention affiliations. Eighteen Baptist leaders representing more than 20 million Baptists across North America backed the group as an alternative to the Southern Baptist Convention. The group held its first meeting in Atlanta, January 30 through February 1, 2008.[139]

Carter's hobbies include painting,[140] fly-fishing, woodworking, cycling, tennis, and skiing.

The Carters have three sons, one daughter, eight grandsons, three granddaughters, and two great-grandsons. They celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary in July 2011, making them the second-longest wed Presidential couple after George and Barbara Bush, a position they have held since passing John and Abigail Adams on July 10, 2000. Their eldest son Jack was the Democratic nominee for U.S. Senate in Nevada in 2006, losing to incumbent John Ensign. Jack's son Jason was elected to the Georgia State Senate in 2010.

Honors and awards

Carter has received honorary degrees from many American and foreign colleges and universities. They include:

- LL.D. (honoris causa) Morehouse College, 1972; Morris Brown College, 1972; University of Notre Dame, 1977; Emory University, 1979; Kwansei Gakuin University, 1981; Georgia Southwestern College, 1981; New York Law School, 1985; Bates College, 1985; Centre College, 1987; Creighton University, 1987; University of Pennsylvania, 1998

- D.E. (honoris causa) Georgia Institute of Technology, 1979

- PhD (honoris causa) Weizmann Institute of Science, 1980; Tel Aviv University, 1983; University of Haifa, 1987

- D.H.L. (honoris causa) Central Connecticut State University, 1985; Trinity College, 1998; Hoseo University, 1998

- Doctor (honoris causa) G.O.C. University, 1995; University of Juba, 2002

- Honorary Fellow of Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 2007

- Honorary Fellow of Mansfield College, Oxford, 2007

Among the honors Carter has received are the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1999 and the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. Others include:

- Freedom of the City of Newcastle upon Tyne, England, 1977

- Silver Buffalo Award, Boy Scouts of America, 1978

- Gold medal, International Institute for Human Rights, 1979

- International Mediation medal, American Arbitration Association, 1979

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Nonviolent Peace Prize, 1979

- International Human Rights Award, Synagogue Council of America, 1979

- Conservationist of the Year Award, 1979

- Harry S. Truman Public Service Award, 1981

- Ansel Adams Conservation Award, Wilderness Society, 1982

- Human Rights Award, International League of Human Rights, 1983

- World Methodist Peace Award, 1985

- Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, 1987

- Edwin C. Whitehead Award, National Center for Health Education, 1989

- Jefferson Award, American Institute of Public Service, 1990

- Liberty Medal, National Constitution Center, 1990

- Spirit of America Award, National Council for the Social Studies, 1990

- Physicians for Social Responsibility Award, 1991

- Aristotle Prize, Alexander S. Onassis Foundation, 1991

- W. Averell Harriman Democracy Award, National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 1992

- Spark M. Matsunaga Medal of Peace, US Institute of Peace, 1993

- Humanitarian Award, CARE International, 1993

- Conservationist of the Year Medal, National Wildlife Federation, 1993

- Rotary Award for World Understanding, 1994

- J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding, 1994

- National Civil Rights Museum Freedom Award, 1994

- UNESCO Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize, 1994

- Great Cross of the Order of Vasco Nunéz de Balboa, Panama, 1995

- Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Award, Africare, 1996

- Humanitarian of the Year, GQ Awards, 1996

- Kiwanis International Humanitarian Award, 1996

- Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development, 1997

- Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Awards for Humanitarian Contributions to the Health of Humankind, National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, 1997

- United Nations Human Rights Award, 1998

- The Hoover Medal, 1998

- The Delta Prize for Global Understanding, University of Georgia, 1999

- International Child Survival Award, UNICEF Atlanta, 1999

- William Penn Mott, Jr., Park Leadership Award, National Parks Conservation Association, 2000[141]

- Zayed International Prize for the Environment, 2001

- Jonathan M. Daniels Humanitarian Award, VMI, 2001

- Herbert Hoover Humanitarian Award, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, 2001

- Christopher Award, 2002

- Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album, National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, 2007[142]

- Berkeley Medal, University of California campus, May 2, 2007

- International Award for Excellence and Creativity, Palestinian Authority, 2009[143]

- Mahatma Gandhi Global Nonviolence Award, Mahatma Gandhi Center for Global Nonviolence, James Madison University (to be awarded September 21, 2009, in Harrisonburg, Virginia, and to be shared with his wife, Rosalynn Carter)

- Recipient of 2009 American Peace Award along with Rosalynn Carter[144]

- International Catalonia Award 2010

In 1998, the US Navy named the third and last Seawolf-class submarine honoring former President Carter and his service as a submariner officer. It became one of the first US Navy vessels to be named for a person living at the time of naming.[145]

World Justice Project

President Jimmy Carter serves as an Honorary Chair for the World Justice Project.[146] The World Justice Project works to lead a global, multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the Rule of Law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity.[147]

Continuity of Government Commission

Carter serves as Honorary Chair for the Continuity of Government Commission (he was co-chair with Gerald Ford until the latter's death). The Commission recommends improvements to continuity of government measures for the federal government.

Participation in ceremonial events

Carter has participated in many ceremonial events such as the opening of his own presidential library and those of Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. He has also participated in many forums, lectures, panels, funerals and other events. Carter delivered a eulogy at the funeral of Coretta Scott King and, most recently, at the funeral of his former political rival, but later his close, personal friend and diplomatic collaborator, Gerald Ford.

Race in politics

Carter ignited debate in September 2009 when he stated, "I think an overwhelming portion of the intensely demonstrated animosity toward President Barack Obama is based on the fact that he is a black man, that he is African-American."[148][149] Obama disagreed with Carter's assessment. On CNN Obama stated, "Are there people out there who don't like me because of race? I'm sure there are...that's not the overriding issue here."[150]

2012 Presidential race

In the Republican party 2012 Presidential primary, Carter endorsed former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney in mid-September, not because he supports Romney, but because he feels Obama's re-election bid would be strengthened in a race against Romney.[151] Carter added that he thinks Romney would lose in a match up against Obama, and that he supports the president's re-election.[152]

2012 Democratic National Convention

Carter will address the gathering in North Carolina by videotape, because he will not attend the convention in person.[153]

Criticisms of President Obama

Carter has criticized the Obama administration for their use of drone strikes against suspected terrorists. Carter also said that he disagrees with President Obama's decision to keep Guantanamo Bay open, saying that the inmates "have been tortured by waterboarding more than 100 times or intimidated with semiautomatic weapons, power drills or threats to sexually assault their mothers." He claimed that the U.S. government had no moral leadership, and was committing human rights violations, and is no longer "the global champion of human rights".[154]

Funeral and burial plans

Carter intends to be buried in front of his home in Plains, Georgia. In contrast, most Presidents since Herbert Hoover have been buried at their presidential library or presidential museum, with the exception of John F. Kennedy, who is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, and Lyndon B. Johnson, who is buried at his own ranch. Both President Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, were born in Plains. Carter also noted that a funeral in Washington, D.C. with visitation at the Carter Center is being planned as well.[155]

See also

- Electoral history of Jimmy Carter

- History of the United States (1964-1980)

- History of the United States (1980-1988)

- Jack Carter (politician) (born 1947; eldest son of former US President Jimmy Carter)

- Jason Carter (politician)

- Jimmy Carter rabbit incident

- Raymond Lee Harvey assassination conspirator

References

- ^ Warner, Greg. "Jimmy Carter says he can 'no longer be associated' with the SBC". Baptist Standard. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

He said he will remain a deacon and Sunday school teacher at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains and support the church's recent decision to send half of its missions contributions to the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "Iran Hostage Crisis ends – History.com This Day in History – 1/20/1981". History.com. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Timeline and History of The Carter Center". The Carter Center. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter and Habitat for Humanity". Habitat for Humanity Int'l.

- ^ "Whois Lookup". Presidentialavenue.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter". USA-Presidents.org.

- ^ "The Nation: Magnus Carter: Jimmy's Roots". Time. August 22, 1977. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ "The California Compatriot" (PDF). California Society SAR. Spring 2007. p. 23. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Jimmy Carter, American Moralist, by Kenneth Earl Morris, 1996, page 23

- ^ "National FFA Organization: Prominent Former Members" (PDF). National FFA Organization.

- ^ Robert D. Hershey Jr (September 26, 1988). "Billy Carter Dies of Cancer at 51; Troubled Brother of a President". The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Cash, John R. with Patrick Carr. (1997) Johnny Cash, the Autobiography. Harper Collins

- ^ DeGregorio, William A. (2005). The Complete Book of US Presidents. Vol. Volume 1. Fort Lee: Barricade Books.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Paul Post, Soldiers of Saratoga County: From Concord to Kabul (2010) p 105

- ^ Great Events from History II: 1945–1966, Frank Northen Magill, 1995, page 554

- ^ Memoirs of a Hayseed Physicist, by Peter Martel, 2008, page 64

- ^ Newspaper article, When Jimmy Carter faced radioactivity head-on, by Arthur Milnes, The Ottawa Citizen, Wednesday, January 28, 2009

- ^ a b Jimmy Carter, American Moralist By Kenneth E. Morris, page 115

- ^ New Crop of Governors – TIME.

- ^ Carter, Jimmy; Richardson, Don (1998). Conversations with Carter. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 1-55587-801-6.

- ^ a b c "Jimmy Carter (b. 1924)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Updated May 9, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ People & Events: James Earl ("Jimmy") Carter Jr. (1924–) – American Experience, PBS. Retrieved March 18, 2006.

- ^ The Claremont Institute – Malaise Forever.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter", Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2005, accessed March 18, 2006. Archived October 31, 2009.

- ^ Till, Brian Michael (2011). Conversations with Power: What Great Presidents and Prime Ministers Can Teach Us about Leadership. Macmillan. p. 180. ISBN 978-0230110588.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ American Experience | Jimmy Carter | Transcript.

- ^ Peter Applebome (January 14, 1990). "In Georgia Reprise, Maddox on Stump". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Race Matters – Lester Maddox, Segregationist and Georgia Governor, Dies at 87.

- ^ "President Jimmy Carter, still far ahead of his time at Black Journalism Review". Blackjournalism.com. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ John-Henry Westen (November 7, 2005). "Jimmy Carter Using Abortion to Split Support for Republicans?". LifeSiteNews.com.

- ^ Skinner, Kudelia, Mesquita, Rice (2007). The Strategy of Campaigning. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11627-0. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carter: Jesus Would Not Approve Of Abortions. CBS Atlanta, March 30, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Hugh S. Sidey (Jan. 22, 2012). "Carter, Jimmy". World Book Student.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "World Book Encyclopedia (Hardcover) [Jimmy Carter entry]". World Book. January 2001. ISBN 0-7166-0101-X.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Our Campaigns – US President – D Convention Race – July 10, 1972.

- ^ Craig Brandon, The Electric Chair: An Unnatural American History, 1999, p. 242.

- ^ "Campaign to End the Death Penalty". Nodeathpenalty.org. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "State by State Database". Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Democrats shift on death penalty". The Boston Globe. December 7, 2003.

- ^ "Carter Nobel Peace Prize speech". CNN. December 10, 2002.

- ^ GAMBRELL, David Henry – Biographical Information.

- ^ Martin, Robert Scott (October 15, 1999). "Celebrities Have Close Encounters, Too". Space.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2004.

- ^ Horvath, Alex (February 7, 2003). "Bolinas man's film says we are not alone". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Stenger, Richard (October 22, 2002). "Clinton aide slams Pentagon's UFO secrecy". CNN. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, July 25, 2007 episode.

- ^ Mohr, Charles (July 16, 1976). "Choice of Mondale Helps To Reconcile the Liberals; Choice of Mondale as Running Mate Helps Carter to Reconcile Liberal Critics Candidate Tells of Painstaking Search In Effort to Avoid Mistake Like 1972's". The New York Times.

- ^ PBS Amex Jimmy Who?.

- ^ "The Playboy Interview: Jimmy Carter." Robert Scheer. Playboy, November 1976, Vol. 23, Iss. 11, pp. 63–86.

- ^ a b American Presidency, Brinkley and Dyer, 2004.

- ^ "Maine college to auction off former White House solar panels". October 28, 2004. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ Burdick, Dave (January 27, 2009). "White House Solar Panels: What Ever Happened To Carter's Solar Thermal Water Heater? (VIDEO)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ Philpott, Tom (August 17, 2011). "Beer Charts of the Day". Motherjones.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ Carter, Jimmy Our Endangered Values: America's Moral Crisis, p. 8, (2005), Simon & Schuster

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/09/16/60minutes/main6872344.shtml. Retrieved 09/16/2010

- ^ Cinnamon Stillwell (December 12, 2006). "Jimmy Carter's Legacy of Failure". Sfgate.com. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ January 21, 2000 (January 21, 2000). "Jimmy Carter: Why He Failed – Brookings Institution". Brookings.edu. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ponnuru, Ramesh (May 28, 2008). "In Carter's Shadow". Time.

- ^ PBS Online/WGBH, "People & Events: Jimmy Carter's Post-Presidency", American Experience: Jimmy Carter, 1999–2001. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (1996). "The rising stock of Jimmy Carter: The 'hands on' legacy of our thirty-ninth President". Diplomatic History. 20 (4): 505–530. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1996.tb00285.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gibb, Lindsay (June 4, 2009). "Monte-Carlo TV fest opens with doc for first time". Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ World Screen http://www.worldscreen.com/articles/display/21252

- ^ a b c "Jimmy Carter:39th president - 1977-1981". London: independent.co.uk. January 22, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ "What History Foretells for Obama's First Job Approval Rating". Gallup.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ "Bush Presidency Closes With 34% Approval, 61% Disapproval". Gallup.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Disaffection of the public - Jimmy Carter - election". Presidentprofiles.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ "Polls: Ford's Image Improved Over Time". CBS News. December 27, 2006.

- ^ Dionne Jr, E. J. (May 18, 1989). "Washington Talk; Carter Begins to Shed Negative Public Image". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ "Time kind to former presidents, CNN poll finds". CNN. January 7, 2009.

- ^ Carter Center Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ The Carter Center: Waging Peace Through Elections. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ Norwegian Nobel Committee, 2002 Nobel Peace Prize announcement,[1], October 11, 2002. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Marion V. Creekmore, A Moment of Crisis: Jimmy Carter, The Power of a Peacemaker, and North Korea's Nuclear Ambitions (2006).

- ^ Washington Monthly Online. ""Rolling Blunder" by Fred Kaplan". Washingtonmonthly.com. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ James Brooke (September 5, 2003). "Carter Issues Warning on North Korea Standoff". The New York Times.

- ^ "Carter Issues Warning on North Korea Standoff"

- ^ Muravchik, Joshua (2007). "Our Worst Ex-President". Commentary. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Justin McCurry (August 27, 2010). "North Korea releases US prisoner after talks with Jimmy Carter". The Guardian. London. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ BBC News Online, "Moderates launch Middle East plan", December 1, 2003. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Douglas G. Brinkley. The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter's Journey to the Nobel Peace Prize (1999), pp. 99–123.

- ^ Kenneth W. Stein, "My Problem with Jimmy Carter's Book", Middle East Quarterly 14.2 (Spring 2007).

- ^ "Israel 'has 150 nuclear weapons'". BBC News Online. May 26, 2008.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter Planning to meet Mashaal", Jerusalem Post, April 9, 2008.

- ^ "PA to Carter: Don't meet with Mashaal." Associated Press. April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Carter: Rice did not advise against Hamas meeting." CNN. April 23, 2008.

- ^ Paris, Lebanon, and Syria Trip Report by Former US President Jimmy Carter: December 5–16, 2008 The Carter Center, December 18, 2008.

- ^ Jimmy Carter says Israel had 150 nuclear weapons, Times.

- ^ "PR-USA.net". PR-USA.net. November 1, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ Jimmy Carter speaks to Forward Magazine[dead link].

- ^ Erick Stakelbeck (March 24, 2011). "Int'l Red Cross Sheltering Hamas Terrorist Officials". Cbn.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ Press Release, African Leaders Gather to Address Great Lakes Crisis, May 2, 1996. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ The Nairobi Agreement, December 8, 1999. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "http://uk.reuters.com/article/2007/10/03/idUKL03712818._CH_.242020071003". Jimmy Carter blocked from meeting Darfur chief. Reuters. Oct.3, 2007.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|title= - ^ Larry Rohter, "Showdown with Haiti: Diplomacy; Carter, in Haiti, pursues peaceful shift", The New York Times, September 18, 1994. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Carter Center News, July–December 2002. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ BBC News Online, Lift Cuba embargo, Carter tells US, May 15, 2002. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Jose De Cordoba, and David Luhnow, "Venezuelans Rush to Vote on Chávez: Polarized Nation Decides Whether to Recall President After Years of Political Rifts", The Wall Street Journal (Eastern edition), New York City, August 16, 2004, p. A11.

- ^ "Venezuelan Audit Confirms Victory", BBC News Online, September 21, 2004. Retrieved November 5, 2005.

- ^ Carter Center (2005). Observing the Venezuela Presidential Recall Referendum: Comprehensive Report. Retrieved January 25, 2006.

- ^ Newman, Lucia (August 17, 2004). "Winner Chavez offers olive branch". CNN. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ M. Barone, "Exit polls in Venezuela," US News & World Report, August 20, 2004.

- ^ "US Poll Firm in Hot Water in Venezuela". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2004. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ "Ecuador and Colombia Presidents Accept President Carter's Proposal to Renew Diplomatic Relations at the Level of Chargé d'Affaires, Immediately and Without Preconditions" (Press release). The Carter Center. June 8, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Colombia, Ecuador restore ties under deal with Carter". Thomson Reuters. June 8, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Cựu Tổng thống Mỹ Jimmy Carter đến Việt Nam Template:Vi

- ^ "Carter slams Clinton pardon". CNN. February 21, 2001. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Jimmy Carter, "Just War -- or a Just War?", The New York Times, March 9, 2003. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Blair Subservient to Bush". The Washington Post. Associated Press. August 27, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Frank Lockwood, "Carter calls Bush administration worst ever", Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 19, 2007. Retrieved August 4, 2008.