Elementary algebra

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

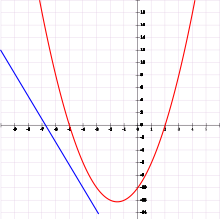

More familiar two-dimensional algebraic equation plot (red line)

Elementary algebra introduces the basic rules and operations of algebra, one of the main branches of mathematics. Whereas arithmetic deals with specific numbers and operators (e.g. 3 + 2 = 5),[1] algebra introduces variables, which are letters that represent non-specific numbers (e.g. 3a + 2a = 5a).[2] Algebra also defines the rules and conventions of how it is written (called algebraic notation). For example, the multiplication symbol, , is sometimes replaced with a dot, or even omitted completely, because its context makes its use obvious (e.g. 3 a may be written 3a).

Elementary algebra is typically taught to secondary school students who are presumed to have little or no formal knowledge of mathematics beyond arithmetic as "algebra". As an introduction, elementary algebra can be found in books from the early 19th century.[3]

Elementary algebra is useful in several ways, including (a) describing generalized problems; if Ann is 3 years older than Bob, this may be written algebraically as a = b + 3. (b) defining mathematical rules such as (a + b) = (b + a) stating that when adding two numbers, the order of numbers does not matter (see commutativity). (c) describing the relationship between numbers such as between temperatures on the Fahrenheit scale (F) and the Centigrade scale (C), given by F = (9C ÷ 5) + 32.

Algebraic notation

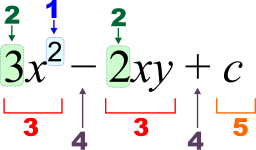

Algebraic notation describes how algebra is written. It follows certain rules and conventions, and has its own terminology. For example, the expression has the following components:

1 – Exponent (power), 2 – Coefficient, 3 – term, 4 – operator, 5 – constant, – variables

A coefficient is a numerical value which multiplies a variable (the operator is omitted). A term is an addend or a summand, a group of coefficients, variables, constants and exponents that may be separated from the other terms by the plus and minus operators.[4] Letters represent variables and constants. By convention, letters at the beginning of the alphabet (e.g. ) are typically used to represent constants, and those toward the end of the alphabet (e.g. and ) are used to represent variables.[5] They are usually written in italics.[6]

Algebraic operations work in the same way as arithmetic operations,[7] such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and exponentiation.[8] and are applied to algebraic variables and terms. Multiplication symbols are usually omitted, and implied when there is no space between two variables or terms, or when a coefficient is used. For example, is written as , and may be written .[9]

Usually terms with the highest power (exponent), are written on the left, for example, is written to the left of . When a coefficient is one, it is usually omitted (e.g. is written ).[10] Likewise when the exponent (power) is one, (e.g. is written ).[11] When the exponent is zero, the result is always 1 (e.g. is always rewritten to ).[12] However , being undefined, should not appear in an expression, and care should be taken in simplifying expressions in which variables may appear in exponents.

Alternative notation

Other types of notation are used in algebraic expressions when the required formatting is not available, or can not be implied, such as where only letters and symbols are available. For example, exponents are usually formatted using superscripts, e.g. . In plain text, and in the TeX mark-up language, the caret symbol "^" represents exponents, so is written as "x^2".[13][14] In programming languages such as Ada,[15] Fortran,[16] Perl,[17] Python [18] and Ruby,[19] a double asterisk is used, so is written as "x**2". Many programming languages, and calculators use a single asterisk to represent the multiplication symbol,[20] and it must be explicitly used, for example, is written "3*x".

Usage

Variables

Elementary algebra builds on and extends arithmetic,[21] by introducing letters called variables, to represent general (non-specified) numbers. This is useful for several reasons.

- Variables represent numbers whose values are not yet known. For example, if the temperature today, T, is 20 degrees higher than the temperature yesterday, Y, then the problem can be described algebraically as .[22]

- Variables describe a general problem,[23] rather than a specific one. For example, it can be stated specifically that 5 minutes is equivalent to seconds. A more general (algebraic) description may state that the number of seconds, , where m is the number of minutes.

- Variables describe mathematical relationships between quantities.[24] For example, the relationship between the circumference, c, and diameter, d, of a circle is described by .

- Variables describe some of the properties of mathematics. For example, a basic property of addition is commutativity which states that the order of numbers being added together does not matter. Commutativity is stated algebraically as .[25]

Evaluating expressions

Algebraic expressions may be evaluated and simplified, based on the basic properties of arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and exponentiation). For example,

- Added terms are simplified using coefficients. For example can be simplified as (where 3 is the coefficient).

- Multiplied terms are simplified using exponents. For example is represented as

- Like terms are added together,[26] for example, is written as , because the terms containing are added together, and, the terms containing are added together.

- Brackets can be "multiplied out", using distributivity. For example, can be written as which can be written as

- Expressions can be factored. For example, , by dividing both terms by can be written as

Equations

An equation states that two expressions are equal using the symbol for equality, (the equals sign).[27] One of the most well-known equations describes Pythagoras' law relating the length of the sides of a right angle triangle:[28]

This equation states that , representing the square of the length of the side that is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle), is equal to the sum (addition) of the square of the other two sides whose lengths are represented by and .

An equation is the claim that two expressions have the same value and are equal. Some equations are true for all values of the involved variables (such as ); such equations are called identities. Conditional equations are true for only some values of the involved variables (e.g. is true only for and . The values of the variables which make the equation true are the solutions of the equation and can be found through equation solving.

Properties of equality

By definition, equality follow a number of "equivalence relations", including (a) reflexive (i.e. ), (b) symmetric (i.e. if then ) (c) transitive (i.e. if and then ).[29] From which:

- if and then and ;

- if then ;

- if two symbols are equal, then one can be substituted for the other.

Properties of inequality

The relations less than and greater than have the property of transivity:[30]

- If and then ;

- If and then ;

- If and then ;

- If and then .

Note that by reversing the equation, we can swap and ,[31] for example:

- is equivalent to

Solving algebraic equations

The following sections lay out examples of some of the types of alegbraic equations you might encounter.

Linear equations with one variable

Linear equations are so-called, because when they are plotted, they describe a straight line (hence linear). The simplest equations to solve are linear equations that have only one variable. They contain only constant numbers and a single variable without an exponent. As an example, consider:

- Problem in words: If you double my son's age and add 4, the resulting answer is 12. How old is my son?

- Equivalent equation: where represent my son's age

To solve this kind of equation, the technique is add, subtract, multiply, or divide both sides of the equation by the same number in order to isolate the variable on one side of the equation. Once the variable is isolated, the other side of the equation is the value of the variable.[32] This problem and its solution are as follows:

| 1. Equation to solve: | |

| 2. Subtract 4 from both sides: | |

| 3. This simplifies to: | |

| 4. Divide both sides by 2: | |

| 5. Simplifies to the solution: |

The general form of a linear equation with one variable, can be written as:

Following the same procedure (i.e. subtract from both sides, and then divide by ), the general solution is given by

Linear equations with two variables

A linear equation with two variables has many (i.e. an infinite number of) solutions.[33] For example:

- Problem in words: I am 22 years older than my son. How old are we?

- Equivalent equation: where is my age, is my son's age.

This can not be worked out by itself. If I told you my son's age, then there would no longer be two unknowns (variables), and the problem becomes a linear equation with just one variable, that can be solved as described above.

To solve a linear equation with two variables (unknowns), requires two related equations. For example, if I also revealed that:

| Problem in words: | In 10 years time, I will be twice as old as my son. |

| Equivalent equation: | |

| Subtract 10 from both sides: | |

| Multiple out brackets: | |

| Simplify: |

Now there are two related linear equations, each with two unknowns, which lets us produce a linear equation with just one variable, by subtracting one from the other (called the elimination method)[34]:

| Second equation | |

| First equation | |

| Subtract the first equation from the second in order to remove | |

| Simplify | |

| Add 12 to both sides | |

| Rearrange |

In other words, my son is aged 12, and as I am 22 years older, I must be 34. In 10 years time, my son will 22, and I will be twice his age, 44. This problem is illustrated on the associated plot of the equations.

For other ways to solve this kind of equations, see below, System of linear equations.

Quadratic equations

A quadratic equation is one which includes a term with an exponent of 2, for example, ,[35] and no term with higher exponent. The name derives from the Latin quadrus, meaning square.[36] In general, a quadratic equation can be expressed in the form ,[37] where is not zero (if it were zero, then the equation would not be quadratic but linear). Because of this a quadratic equation must contain the term , which is known as the quadratic term. Hence , and so we may divide by and rearrange the equation into the standard form

where and . Solving this, by a process known as completing the square, leads to the quadratic formula

where the symbol "±" indicates that both

are solutions of the quadratic equation.

Quadratic equations can also be solved using factorization (the reverse process of which is expansion, but for two linear terms is sometimes denoted foiling). As an example of factoring:

Which is the same thing as

It follows from the zero-product property that either or are the solutions, since precisely one of the factors must be equal to zero. All quadratic equations will have two solutions in the complex number system, but need not have any in the real number system. For example,

has no real number solution since no real number squared equals −1. Sometimes a quadratic equation has a root of multiplicity 2, such as:

For this equation, −1 is a root of multiplicity 2. This means −1 appears two times.

Exponential and logarithmic equations

An exponential equation is one which has the form for ,[38] which has solution

when . Elementary algebraic techniques are used to rewrite a given equation in the above way before arriving at the solution. For example, if

then, by subtracting 1 from both sides of the equation, and then dividing both sides by 3 we obtain

whence

or

A logarithmic equation is an equation of the form for , which has solution

For example, if

then, by adding 2 to both sides of the equation, followed by dividing both sides by 4, we get

whence

from which we obtain

Radical equations

A radical equation is one that includes a radical (square root) sign, , which includes cube roots, and nth roots, . Recall that an nth root can be rewritten in exponential format, so that is equivalent to . Combined with regular exponents (powers), then (the square root of cubed), can be rewritten as .[39] So the general form of radical equation is (equivalent to ) where and integers, and which has solution:

| is odd | is even and |

or

| or

|

For example, if:

then

- .

System of linear equations

There are different methods to solve a system of linear equations with two variables.

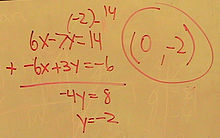

Elimination method

An example of solving a system of linear equations is by using the elimination method:

Multiplying the terms in the second equation by 2:

Adding the two equations together to get:

which simplifies to

Since the fact that is known, it is then possible to deduce that by either of the original two equations (by using 2 instead of ) The full solution to this problem is then

Note that this is not the only way to solve this specific system; could have been solved before .

Substitution method

Another way of solving the same system of linear equations is by substitution.

An equivalent for can be deduced by using one of the two equations. Using the second equation:

Subtracting from each side of the equation:

and multiplying by −1:

Using this value in the first equation in the original system:

Adding 2 on each side of the equation:

which simplifies to

Using this value in one of the equations, the same solution as in the previous method is obtained.

Note that this is not the only way to solve this specific system; in this case as well, could have been solved before .

Other types of systems of linear equations

Unsolvable systems

In the above example, it is possible to find a solution. However, there are also systems of equations which do not have a solution. An obvious example would be:

The second equation in the system has no possible solution. Therefore, this system can't be solved. However, not all incompatible systems are recognized at first sight. As an example, the following system is studied:

When trying to solve this (for example, by using the method of substitution above), the second equation, after adding on both sides and multiplying by −1, results in:

And using this value for in the first equation:

No variables are left, and the equality is not true. This means that the first equation can't provide a solution for the value for obtained in the second equation.

Undetermined systems

There are also systems which have multiple or infinite solutions, in contrast to a system with a unique solution (meaning, two unique values for and ) For example:

Isolating in the second equation:

And using this value in the first equation in the system:

The equality is true, but it does not provide a value for . Indeed, one can easily verify (by just filling in some values of ) that for any there is a solution as long as . There are infinite solutions for this system.

Over- and underdetermined systems

Systems with more variables than the number of linear equations do not have a unique solution. An example of such a system is

Such a system is called underdetermined; when trying to find a solution, one or more variables can only be expressed in relation to the other variables, but cannot be determined numerically. Incidentally, a system with a greater number of equations than variables, in which necessarily some equations are sums or multiples of others, is called overdetermined.

Relation between solvability and multiplicity

Given any system of linear equations, there is a relation between multiplicity and solvability.

If one equation is a multiple of the other (or, more generally, a sum of multiples of the other equations), then the system of linear equations is undetermined, meaning that the system has infinitely many solutions. Example:

has solutions for such as (1, 1), (0, 2), (1.8, 0.2), (4, −2), (−3000.75, 3002.75), and so on.

When the multiplicity is only partial (meaning that for example, only the left hand sides of the equations are multiples, while the right hand sides are not or not by the same number) then the system is unsolvable. For example, in

the second equation yields that which is in contradiction with the first equation. Such a system is also called inconsistent in the language of linear algebra. When trying to solve a system of linear equations it is generally a good idea to check if one equation is a multiple of the other. If this is precisely so, the solution cannot be uniquely determined. If this is only partially so, the solution does not exist.

This, however, does not mean that the equations must be multiples of each other to have a solution, as shown in the sections above; in other words: multiplicity in a system of linear equations is not a necessary condition for solvability.

See also

- History of elementary algebra

- Binary operation

- Gaussian elimination

- Mathematics education

- Number line

- Polynomial

References

- Leonhard Euler, Elements of Algebra, 1770. English translation Tarquin Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-899618-79-8, also online digitized editions[40] 2006,[41] 1822.

- Charles Smith, A Treatise on Algebra, in Cornell University Library Historical Math Monographs.

- Redden, John. Elementary Algebra. Flat World Knowledge, 2011

- ^ H.E. Slaught and N.J. Lennes, Elementary algebra, Publ. Allyn and Bacon, 1915, page 1 (republished by Forgotten Books)

- ^ Lewis Hirsch, Arthur Goodman, Understanding Elementary Algebra With Geometry: A Course for College Students, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2005, ISBN 0534999727, 9780534999728, 654 pages, page 2

- ^ Louis Benjamin Francoeur, (Translated by Ralph Blakelock), A complete course of pure mathematics, Volume 1, "Book II. Elementary algebra", Publisher: W. P. Grant, 1829

- ^ Richard N. Aufmann, Joanne Lockwood, Introductory Algebra: An Applied Approach, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2010, ISBN 1439046042, 9781439046043, page 78

- ^ William L. Hosch (editor), The Britannica Guide to Algebra and Trigonometry, Britannica Educational Publishing, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2010, ISBN 1615302190, 9781615302192, page 71

- ^ James E. Gentle, Numerical Linear Algebra for Applications in Statistics, Publisher: Springer, 1998, ISBN 0387985425, 9780387985428, 221 pages, [James E. Gentle page 183]

- ^ Horatio Nelson Robinson, New elementary algebra: containing the rudiments of science for schools and academies, Ivison, Phinney, Blakeman, & Co., 1866, page 7

- ^ Ron Larson, Robert Hostetler, Bruce H. Edwards, Algebra And Trigonometry: A Graphing Approach, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2007, ISBN 061885195X, 9780618851959, 1114 pages, page 6

- ^ Sin Kwai Meng, Chip Wai Lung, Ng Song Beng, "Algebraic notation", in Mathematics Matters Secondary 1 Express Textbook, Publisher Panpac Education Pte Ltd, ISBN 9812738827, 9789812738820, page 68

- ^ David Alan Herzog, Teach Yourself Visually Algebra, Publisher John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 0470185597, 9780470185599, 304 pages, page 72

- ^ John C. Peterson, Technical Mathematics With Calculus, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2003, ISBN 0766861899, 9780766861893, 1613 pages, page 31

- ^ Jerome E. Kaufmann, Karen L. Schwitters, Algebra for College Students, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2010, ISBN 0538733543, 9780538733540, 803 pages, page 222

- ^ Ramesh Bangia, Dictionary of Information Technology, Publisher Laxmi Publications, Ltd., 2010, ISBN 9380298153, 9789380298153, page 212

- ^ George Grätzer, First Steps in LaTeX, Publisher Springer, 1999, ISBN 0817641327, 9780817641320, page 17

- ^ S. Tucker Taft, Robert A. Duff, Randall L. Brukardt, Erhard Ploedereder, Pascal Leroy, Ada 2005 Reference Manual, Volume 4348 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Publisher Springer, 2007, ISBN 3540693351, 9783540693352, page 13

- ^ C. Xavier, Fortran 77 And Numerical Methods, Publisher New Age International, 1994, ISBN 812240670X, 9788122406702, page 20

- ^ Randal Schwartz, brian foy, Tom Phoenix, Learning Perl, Publisher O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2011, ISBN 1449313140, 9781449313142, page 24

- ^ Matthew A. Telles, Python Power!: The Comprehensive Guide, Publisher Course Technology PTR, 2008, ISBN 1598631586, 9781598631586, page 46

- ^ Kevin C. Baird, Ruby by Example: Concepts and Code, Publisher No Starch Press, 2007, ISBN 1593271484, 9781593271480, page 72

- ^ William P. Berlinghoff, Fernando Q. Gouvêa, Math through the Ages: A Gentle History for Teachers and Others, Publisher MAA, 2004, ISBN 0883857367, 9780883857366, page 75

- ^ Thomas Sonnabend, Mathematics for Teachers: An Interactive Approach for Grades K-8, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2009, ISBN 0495561665, 9780495561668, 759 pages, page xvii

- ^ Lewis Hirsch, Arthur Goodman, Understanding Elementary Algebra With Geometry: A Course for College Students, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2005, ISBN 0534999727, 9780534999728, 654 pages, page 48

- ^ Lawrence S. Leff, College Algebra: Barron's Ez-101 Study Keys, Publisher: Barron's Educational Series, 2005, ISBN 0764129147, 9780764129148, 230 pages, page 2

- ^ Ron Larson, Kimberly Nolting, Elementary Algebra, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2009, ISBN 0547102275, 9780547102276, 622 pages, page 210

- ^ Charles P. McKeague, Elementary Algebra, Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2011, ISBN 0840064217, 9780840064219, 571 pages, page 49

- ^ Andrew Marx, Shortcut Algebra I: A Quick and Easy Way to Increase Your Algebra I Knowledge and Test Scores, Publisher Kaplan Publishing, 2007, ISBN 1419552880, 9781419552885, 288 pages, page 51

- ^ Mark Clark, Cynthia Anfinson, Beginning Algebra: Connecting Concepts Through Applications, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2011, ISBN 0534419380, 9780534419387, 793 pages, page 134

- ^ Alan S. Tussy, R. David Gustafson, Elementary and Intermediate Algebra, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2012, ISBN 1111567689, 9781111567682, 1163 pages, page 493

- ^ Douglas Downing, Algebra the Easy Way, Publisher Barron's Educational Series, 2003, ISBN 0764119729, 9780764119729, 392 pages, page 20

- ^ Ron Larson, Robert Hostetler, Intermdiate Algebra, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2008, ISBN 0618753524, 9780618753529, 857 pages, page 96

- ^ Chris Carter, Physics: Facts and Practice for A Level, Publisher Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 019914768X, 9780199147687, 144 pages, page 50

- ^ Slavin, Steve (1989). All the Math You'll Ever Need. John Wiley & Sons. p. 72. ISBN 0-471-50636-2.

- ^ Sinha, The Pearson Guide to Quantitative Aptitude for CAT 2/ePublisher: Pearson Education India, 2010, ISBN 8131723666, 9788131723661, 599 pages, page 195

- ^ Cynthia Y. Young, Precalculus, Publisher John Wiley & Sons, 2010, ISBN 0471756849, 9780471756842, 1175 pages, page 699

- ^ Mary Jane Sterling, Algebra II For Dummies, Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, 2006, ISBN 0471775819, 9780471775812, 384 pages, page 37

- ^ John T. Irwin, The Mystery to a Solution: Poe, Borges, and the Analytic Detective Story, Publisher JHU Press, 1996, ISBN 0801854660, 9780801854668, 512 pages, page 372

- ^ Sharma/khattar, The Pearson Guide To Objective Mathematics For Engineering Entrance Examinations, 3/E, Publisher Pearson Education India, 2010, ISBN 8131723631, 9788131723630, 1248 pages, page 621

- ^ Aven Choo, LMAN OL Additional Maths Revision Guide 3, Publisher Pearson Education South Asia, 2007, ISBN 9810600011, 9789810600013, page 105

- ^ John C. Peterson, Technical Mathematics With Calculus, Publisher Cengage Learning, 2003, ISBN 0766861899, 9780766861893, 1613 pages, page 525

- ^ Euler's Elements of Algebra

- ^ Elements of algebra – Leonhard Euler, John Hewlett, Francis Horner, Jean Bernoulli, Joseph Louis Lagrange – Google Books

External links

- Elementary Algebra An open textbook published by Flat World Knowledge.

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a55f866116e7a86823816615dd98fcccde75473)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7b3ba2638d05cd9ed8dafae7e34986399e48ea99)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{2}]{x^{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6689fad02ba04851cff57ef80164ad8b1049f847)

![{\displaystyle a={\sqrt[{n}]{x^{m}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9fe94d50c3e43af84f3d04ade9617394e41ffe39)

![{\displaystyle x={\sqrt[{m}]{a^{n}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cd09966c4c1505671df512298eda6fc36dd1a456)

![{\displaystyle x=\left({\sqrt[{m}]{a}}\right)^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e2527ddffa8d54db65cc7c01b9d438378c796abb)

![{\displaystyle x=\pm {\sqrt[{m}]{a^{n}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/26a5a6e030a43a7f81c76d76ef0c2c05d645110e)

![{\displaystyle x=\pm \left({\sqrt[{m}]{a}}\right)^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/124b0e0acfea5e41274b8d6593ced4b49834021e)