Massachusetts Institute of Technology

42°21′35″N 71°05′32″W / 42.35982°N 71.09211°W

| |

| Motto | Mens et Manus (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Mind and Hand[1] |

| Type | Private |

| Established | 1861 (opened 1865) |

| Endowment | US$ 10.3 billion (2012)[2] |

| President | L. Rafael Reif |

| Provost | Chris A. Kaiser |

Academic staff | 1,018[3] |

| Students | 10,894[4] |

| Undergraduates | 4,384[4] |

| Postgraduates | 6,510 |

| Location | , Massachusetts , U.S. |

| Campus | Urban, 168 acres (68.0 ha)[5] |

| Nobel Laureates | 77[6] |

| Colors | Cardinal Red and Steel Gray[a] |

| Affiliations | NEASC, AAU, COFHE, APLU |

| Mascot | Tim the Beaver[8] |

| Website | MIT.edu |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, also known as MIT, is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.

Founded in 1861 in response to the increasing industrialization of the United States, the institute adopted the European polytechnic university model and emphasized laboratory instruction from an early date.[9] MIT's early emphasis on applied technology at the undergraduate and graduate levels led to close cooperation with industry. Curricular reforms under Karl Compton and Vannevar Bush in the 1930s re-emphasized basic scientific research.[10] MIT was elected to the Association of American Universities in 1934. Researchers were involved in efforts to develop computers, radar, and inertial guidance in connection with defense research during World War II and the Cold War. Post-war defense research contributed to the rapid expansion of the faculty and campus under James Killian.

The current 168-acre (68.0 ha) campus opened in 1916 and extends over 1 mile (1.6 km) along the northern bank of the Charles River basin.[5] In the past 60 years, MIT's educational disciplines have expanded beyond the physical sciences and engineering into fields such as biology, economics, linguistics, political science, and management.

MIT enrolled 4,384 undergraduates and 6,510 graduate students for the 2011–2012 school year.[4] MIT received 17,909 undergraduate applicants for the class of 2015, with only 1,742 offered admittance, an acceptance rate of 9.7%.[11] It employs around 1,000 faculty members.[3] 77 Nobel laureates, 52 National Medal of Science recipients, 45 Rhodes Scholars, and 38 MacArthur Fellows are currently or have previously been affiliated with the university.[3][6][12]

MIT has a strong entrepreneurial culture. The aggregated revenues of companies founded by MIT alumni would rank as the eleventh-largest economy in the world.[13][14] MIT managed $718.2 million in research expenditures and an $8.0 billion endowment in 2009.[15][16]

The "Engineers"[17] sponsor 33 sports, most teams of which compete in the NCAA Division III's New England Women's and Men's Athletic Conference; the Division I rowing programs compete as part of the EARC and EAWRC.

History

Foundation and vision

...a school of industrial science [aiding] the advancement, development and practical application of science in connection with arts, agriculture, manufactures, and commerce.

— [18], Act to Incorporate the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Acts of 1861, Chapter 183

In 1859, various individuals and Bostonian organizations submitted to the Massachusetts General Court a proposal to use newly opened lands in Back Bay, Boston for a "Conservatory of Art and Science", but the proposal failed.[19][20] A later proposal by William Barton Rogers led to a charter for the incorporation of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which was signed by the governor of Massachusetts on April 10, 1861.[21]

Rogers sought to establish a new institution of higher education to address the challenges posed by the mid-19th century's rapid scientific and technological advances.[22][23] Though he valued first-hand experience as part of a proper education, he did not intend to found a professional school, but advocated instruction in useful knowledge that combined elements of both professional and liberal education,[24] writing that "The true and only practicable object of a polytechnic school is, as I conceive, the teaching, not of the minute details and manipulations of the arts, which can be done only in the workshop, but the inculcation of those scientific principles which form the basis and explanation of them, and along with this, a full and methodical review of all their leading processes and operations in connection with physical laws."[25] The Rogers Plan, as it came to be known, reflected the German research university model, emphasizing an independent faculty engaged in research as well as instruction oriented around seminars and laboratories.[26]

Early developments

Just two days after the issuance of the charter, the first battle of the Civil War broke out. After years of delay caused by wartime funding and staffing difficulties, MIT's first classes were held in rented space at the Mercantile Building in downtown Boston in 1865.[27] Though it was a private institution to be located in the middle of urban Boston, the new institute had a mission that matched the intent of the 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act to fund institutions "to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes", and was thus named a land-grant school.[28][b] In 1866, the proceeds from land sales went toward new buildings in the Back Bay neighborhood.[29]

MIT soon came to be called "Boston Tech".[29] After surviving a period of financial uncertainties, the institute saw significant expansion in the last two decades of the 19th century under President Francis Amasa Walker.[30] Programs in electrical, chemical, marine, and sanitary engineering were introduced,[31][32] new buildings were built, and the size of the student body increased to well over 1000.[30] The curriculum became increasingly vocational; less and less focus was placed on theoretical topics.[33] During these "Boston Tech" years, MIT faculty and alumni repeatedly rejected overtures from former MIT faculty turned Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, to merge MIT with Harvard College's Lawrence Scientific School.[34]

MIT reinforced its independence in 1916 when it moved to its new campus on a mile-long tract on the Cambridge side of the Charles River,[36] almost entirely on landfill.[c] The neoclassical "New Technology" campus was funded by donations from industrialist George Eastman and designed by William W. Bosworth.[38]

Curricular reforms

In the 1930s, President Karl Taylor Compton and Vice-President (effectively Provost) Vannevar Bush reformed the applied technology curriculum by re-emphasizing the importance of "pure" sciences like physics and chemistry and by reducing the vocational practice required in shops and drafting studios.[10] Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, the Compton reforms "renewed confidence in the ability of the Institute to develop leadership in science as well as in engineering."[39] The expansion and reforms cemented MIT's academic reputation[10], though unlike Ivy League schools, MIT catered more to middle-class families, and depended more on tuition than on endowments or grants.[40] The school was elected to the Association of American Universities in 1934.[41]

Still, as late as 1949, the Lewis Committee lamented in its report on the state of education at MIT that "the Institute is widely conceived as basically a vocational school", a "partly unjustified" perception the committee sought to change. The report comprehensively reviewed the undergraduate curriculum, recommended offering a broader education, and warned against letting engineering and government-sponsored research detract from the sciences and humanities.[42][43] The School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences and the MIT Sloan School of Management were formed in 1950 to compete with the powerful Schools of Science and Engineering. Previously marginalized faculties in the areas of economics, management, political science, and linguistics emerged into cohesive and assertive departments by attracting respected professors and launching competitive graduate programs.[44][45] The School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences continued to develop under the successive terms of the more humanistically oriented presidents Howard W. Johnson and Jerome Wiesner between 1966 and 1980.[46]

Defense research

MIT's involvement in military research surged during World War II. In 1941, Vannevar Bush was appointed head of the federal Office of Scientific Research and Development and directed funding to only a select group of universities, including MIT.[47] Engineers and scientists from across the country gathered at MIT's Radiation Laboratory, established in 1940 to assist the British military in developing microwave radar. The work done there significantly impacted both the war and subsequent research in the area.[48] Other defense projects included gyroscope-based and other complex control systems for gunsight, bombsight, and inertial navigation under Charles Stark Draper's Instrumentation Laboratory;[49][50] the development of a digital computer for flight simulations under Project Whirlwind;[51] and high-speed and high-altitude photography under Harold Edgerton.[52][53] By the end of the war, MIT became the nation's largest wartime R&D contractor (attracting some criticism of Bush),[47] employing nearly 4000 in the Radiation Laboratory alone[48] and receiving in excess of $100 million ($1.2 billion in 2012 dollars) before 1946.[39] Work on defense projects continued even after then. Post-war government-sponsored research at MIT included SAGE and guidance systems for ballistic missiles and Project Apollo.[54]

These activities affected MIT profoundly. A 1949 report noted the lack of "any great slackening in the pace of life at the Institute" to match the return to peacetime, remembering the "academic tranquillity of the prewar years", though acknowledging the significant contributions of military research to the increased emphasis on graduate education and rapid growth of personnel and facilities.[55] Indeed, the faculty doubled and the graduate student body quintupled during the terms of Karl Taylor Compton, president of MIT between 1930 and 1948, James Rhyne Killian, president from 1948 to 1957, and Julius Adams Stratton, chancellor from 1952 to 1957, whose institution-building strategies shaped the expanding university. By the 1950s, MIT no longer merely benefited the industries it had worked so closely with three decades prior, and was much closer to its new patrons, philanthropic foundations and the federal government.[56]

In late 1960s and early 1970s, student and faculty activists protested against the Vietnam War and MIT's defense research.[57][58] The Union of Concerned Scientists was founded on March 4, 1969 during a meeting of faculty members and students seeking to shift the emphasis on military research towards environmental and social problems.[59] MIT ultimately divested itself from the Instrumentation Laboratory and moved all classified research off-campus to the Lincoln Laboratory facility in 1973 in response to the protests,[60][61] and the student body, faculty, and administration remained comparatively unpolarized during what was a tumultuous time for many other universities.[57][62]

Recent history

MIT has kept pace with and helped to advance the digital age. In addition to developing the predecessors to modern computing and networking technologies,[63][64] students, staff, and faculty members at Project MAC, the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, and the Tech Model Railroad Club wrote some of the earliest interactive computer video games like Spacewar! and created much of modern hacker slang and culture.[65] Several major computer-related organizations have originated at MIT since the 1980s: Richard Stallman's GNU Project and the subsequent Free Software Foundation were founded in the mid-1980s at the AI Lab; the MIT Media Lab was founded in 1985 by Nicholas Negroponte and Jerome Wiesner to promote research into novel uses of computer technology;[66] the World Wide Web Consortium standards organization was founded at the Laboratory for Computer Science in 1994 by Tim Berners-Lee;[67] the OpenCourseWare project has made course materials for over 2,000 MIT classes available online free of charge since 2002;[68] and the One Laptop per Child initiative to expand computer education and connectivity to children worldwide was launched in 2005.[69]

MIT was named a sea-grant college in 1976 to support its programs in oceanography and marine sciences and was named a space-grant college in 1989 to support its aeronautics and astronautics programs.[70][71] Despite diminishing government financial support over the past quarter century, MIT launched several successful development campaigns to significantly expand the campus: new dormitories and athletics buildings on west campus; the Tang Center for Management Education; several buildings in the northeast corner of campus supporting research into biology, brain and cognitive sciences, genomics, biotechnology, and cancer research; and a number of new "backlot" buildings on Vassar Street including the Stata Center.[72] Construction on campus in the 2000s included expansions of the Media Lab, the Sloan School's eastern campus, and graduate residences in the northwest.[73][74] In 2006, President Hockfield launched the MIT Energy Research Council to investigate the interdisciplinary challenges posed by increasing global energy consumption.[75]

In 2001, inspired by the open source and open access movements,[76] MIT launched OpenCourseWare to make the lecture notes, problem sets, syllabuses, exams, and lectures from the great majority of its courses available online for no charge, though without any formal accreditation for coursework completed.[77] While the cost of supporting and hosting the project is high,[78] OCW expanded in 2005 to include other universities as a part of the OpenCourseWare Consortium, which currently includes more than 250 academic institutions with content available in least six languages.[79] In 2011, MIT announced it would offer formal certification (but not credits or degrees) to online participants completing coursework in its "MITx" program, for a modest fee.[80] The "edX" online platform supporting MITx will initially be developed in partnership with Harvard and its analogous "Harvardx" initiative. The courseware platform is open source, and other universities will be encouraged to add their own course content.[81]

Campus

MIT's 168-acre (68.0 ha) campus spans approximately a mile of the north side of the Charles River basin in the city of Cambridge.[82] The campus is divided roughly in half by Massachusetts Avenue, with most dormitories and student life facilities to the west and most academic buildings to the east. The bridge closest to MIT is the Harvard Bridge, which is known for being marked off in a non-standard unit of length – the smoot.[83][84] The Kendall MBTA Red Line station is located on the far northeastern edge of the campus in Kendall Square. The Cambridge neighbourhoods surrounding MIT are a mixture of high tech companies occupying both modern office and rehabilitated industrial buildings as well as socio-economically diverse residential neighbourhoods.[85][86]

Each building at has a number (possibly preceded by a W, N, E, or NW) designation and most have a name as well. Typically, academic and office buildings are referred to primarily by number while residence halls are referred to by name. The organization of building numbers roughly corresponds to the order in which the buildings were built and their location relative (north, west, and east) to the original center cluster of Maclaurin buildings.[87] Many of the buildings are connected above ground as well as through an extensive network of underground tunnels, providing protection from the Cambridge weather as well as a venue for roof and tunnel hacking.[88][89]

MIT's on-campus nuclear reactor[90] is one of the most powerful university-based nuclear reactors in the United States. The prominence of the reactor's containment building in a densely populated area has been controversial,[91] but MIT maintains that it is well-secured.[92] Other notable campus facilities include a pressurized wind tunnel and a towing tank for testing ship and ocean structure designs.[93][94] MIT's campus-wide wireless network was completed in the fall of 2005 and consists of nearly 3,000 access points covering 9,400,000 square feet (870,000 m2) of campus.[95]

In 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency sued MIT for violating Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act with regard to its hazardous waste storage and disposal procedures.[96] MIT settled the suit by paying a $155,000 fine and launching three environmental projects.[97] In connection with capital campaigns to expand the campus, the Institute has also extensively renovated existing buildings to improve their energy efficiency. MIT has also taken steps to reduce its environmental impact by running alternative fuel campus shuttles, subsidizing public transportation passes, and building a low-emission cogeneration plant that serves most of the campus electricity, heating, and cooling requirements.[98]

Between 2007 and 2009,[needs update] campus security and local police received reports of 8 forcible sex offences, 5 robberies, 9 aggravated assaults, 409 burglaries, 2 cases of arson, and 15 cases of motor vehicle theft, affecting a community of around 13,000 students and employees.[99]

Architecture

MIT's School of Architecture, now the School of Architecture and Planning, was the first in the United States,[100] and it has a history of commissioning progressive buildings.[101][102] The first buildings constructed on the Cambridge campus, completed in 1916, are sometimes called the "Maclaurin buildings" after Institute president Richard Maclaurin who oversaw their construction. Designed by William Welles Bosworth, these imposing buildings were built of reinforced concrete, a first for a non-industrial – much less university – building in the US.[103] Bosworth's design was influenced by the City Beautiful Movement of the early 1900s,[103] and features the Pantheon-esque Great Dome housing the Barker Engineering Library. The Great Dome overlooks Killian Court, where commencement is held each year. The friezes of the limestone-clad buildings around Killian Court are engraved with the names of important scientists and philosophers.[d] The imposing Building 7 atrium along Massachusetts Avenue is regarded as the entrance to the Infinite Corridor and the rest of the campus.[86]

Alvar Aalto's Baker House (1947), Eero Saarinen's Chapel and Auditorium (1955), and I.M. Pei's Green, Dreyfus, Landau, and Wiesner buildings represent high forms of post-war modernist architecture.[106][107][108] More recent buildings like Frank Gehry's Stata Center (2004), Steven Holl's Simmons Hall (2002), Charles Correa's Building 46 (2005), Fumihiko Maki's Media Lab Extension (2009) stand out among the Boston area's classical architecture and serve as examples of contemporary campus "starchitecture".[101][109] These buildings have not always been well received;[110][111] in 2010, The Princeton Review included MIT in a list of twenty schools whose campuses are "tiny, unsightly, or both".[112]

Housing

Undergraduates are guaranteed four-year housing in one of MIT's 12 undergraduate dormitories,[113] Those living on campus can receive support and mentoring from live-in graduate student tutors, resident advisors, and faculty housemasters.[114] Because housing assignments are made based on the preferences of the students themselves, diverse social atmospheres can be sustained in different living groups; for example, according to the Yale Daily News Staff's The Insider's Guide to the Colleges, 2010, "The split between East Campus and West Campus is a significant characteristic of MIT. East Campus has gained a reputation as a thriving counterculture."[115] MIT also has 5 dormitories for single graduate students and 2 apartment buildings on campus for married student families.[116]

MIT has a very active Greek and co-op housing system which includes 36 fraternities, sororities, and independent living groups (FSILGs).[117] In 2009, 92% of all undergraduates lived on MIT-affiliated housing, 50 percent of the men in fraternities and 34% of the women in sororities.[118] Most FSILGs are located across the river in the Back Bay owing to MIT's history there, and there is also a cluster of fraternities on MIT's West Campus.[119] After the 1997 death of Scott Krueger, a new member at the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity, MIT required all freshmen to live in the dormitory system starting in 2002.[120] Because FSILGs had previously housed as many as 300 freshmen off-campus, the new policy did not take effect until 2002 after Simmons Hall opened.[121]

Organization and administration

MIT is chartered as a non-profit organization and is owned and governed by a privately appointed board of trustees known as the MIT Corporation.[122] The current board consists of 43 members elected to five-year terms,[123] 25 life members who vote until their 75th birthday,[124] 3 elected officers (President, Treasurer, and Secretary),[125] and 4 ex officio members (the president of the alumni association, the Governor of Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Secretary of Education, and the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court).[126][127] The board is chaired by John S. Reed, the former chairman of the New York Stock Exchange and Citigroup.[128][129] The corporation approves the budget, new programs, degrees, and faculty appointments as well as electing the President to serve as the chief executive officer of the university and presiding over the Institute's faculty.[86][130] MIT's endowment and other financial assets are managed through a subsidiary MIT Investment Management Company (MITIMCo).[131] Valued at $9.7 billion in 2011, MIT's endowment is the sixth-largest among American colleges and universities.[15][132]

MIT has five schools (Science, Engineering, Architecture and Planning, Management, and Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences) and one college (Whitaker College of Health Sciences and Technology), but no schools of law or medicine.[133][e] While faculty committees assert substantial control over many areas of MIT's curriculum, research, student life, and administrative affairs,[135] the chair of each of MIT's 32 academic departments reports to the dean of that department's school, who in turn reports to the Provost under the President.[136] The current president is L. Rafael Reif, who formerly served as provost under President Susan Hockfield, the first woman to hold the post.[137][138]

Collaborations

The university historically pioneered research and training collaborations between academia, industry and government.[139][140] Fruitful collaborations with industrialists like Alfred P. Sloan and Thomas Alva Edison led President Compton to establish an Office of Corporate Relations and an Industrial Liaison Program in the 1930s and 1940s that now allows over 600 companies to license research and consult with MIT faculty and researchers.[10][141] Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, American politicians and business leaders accused MIT and other universities of contributing to a declining economy by transferring taxpayer-funded research and technology to international – especially Japanese — firms that were competing with struggling American businesses.[142][143] On the other hand, MIT's extensive collaboration with the federal government on research projects has led to several MIT leaders serving as Presidential scientific advisers since 1940.[f] MIT established a Washington Office in 1991 to continue to lobby for research funding and national science policy.[145][146]

The Justice Department began an antitrust investigation in 1989, and in 1991 filed an antitrust suit against MIT, the eight Ivy League colleges, and eleven other institutions for allegedly engaging in price-fixing in their annual "Overlap Meetings", which were held to prevent bidding wars over promising prospective students from consuming funds for need-based scholarships.[147][148] While the Ivy League institutions settled,[149] MIT contested the charges, arguing that the practice was not anti-competitive because it ensured the availability of aid for the greatest number of students.[150][151] MIT ultimately prevailed when the Justice Department dropped the case in 1994.[152][153]

MIT's proximity[g] to Harvard University ("the other school up the river") has led to a substantial number of research collaborations such as the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology and Broad Institute.[154] In addition, students at the two schools can cross-register for credits toward their own school's degrees without any additional fees.[154] A cross-registration program between MIT and Wellesley College has also existed since 1969, and in 2002 the Cambridge–MIT Institute launched an undergraduate exchange program between MIT and the University of Cambridge.[154] MIT has more modest cross-registration programs with Boston University, Brandeis University, Tufts University, Massachusetts College of Art, and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[154] MIT maintains substantial research and faculty ties with independent research organizations in the Boston-area like the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution as well as international research and educational collaborations through the Singapore-MIT Alliance, MIT-Politecnico di Milano,[154][155] MIT-Zaragoza International Logistics Program, and other countries through the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) program.[154][156]

The mass-market magazine Technology Review is published by MIT through a subsidiary company, as is a special edition that also serves as an alumni magazine.[157][158] The MIT Press is a major university press, publishing over 200 books and 30 journals annually emphasizing science and technology as well as arts, architecture, new media, current events, and social issues.[159]

Academics

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[160] | 11 |

| U.S. News & World Report[161] | 6 |

| Washington Monthly[162] | 15 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[163] | 3 |

| QS[164] | 1 |

| THE[165] | 7 |

MIT is a large, highly residential, research university with a majority of enrollments in graduate and professional programs.[166] The university has been accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges since 1929.[167][168] MIT operates on a 4–1–4 academic calendar with the fall semester beginning after Labor Day and ending in mid-December, a 4-week "Independent Activities Period" in the month of January, and the spring semester beginning in early February and ending in late May.[169]

MIT places among the top ten in many overall rankings of universities (see right) and rankings based on students' revealed preferences.[170][171] For several years, U.S.News & World Report, the QS World University Rankings, and the Academic Ranking of World Universities have ranked MIT's School of Engineering first, as did the 1995 National Research Council report. In the same lists, MIT's strongest showings apart from in engineering are in computer science, the natural sciences, business, economics, linguistics, mathematics, and, to a lesser extent, political science and philosophy.[172][173][174][175][176][177]

MIT students refer to both their majors and classes using numbers or acronyms alone.[178] Departments and their corresponding majors are numbered in the approximate order their foundation; for example, Civil and Environmental Engineering is Course 1, while Linguistics and Philosophy is Course 24.[179] Students majoring in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), the most popular department, collectively identify themselves as "Course 6". MIT students use a combination of the department's course number and the number assigned to the class to identify their subjects; the introductory calculus-based classical mechanics course is simply "8.01" at MIT.[180][h]

Undergraduate program

The four year, full-time undergraduate program maintains a balance between professional majors and those in the arts and sciences, and is selective, admitting few transfer students[166] and 9.7% of its applicants in the 2010–2011 application season.[11] MIT offers 44 undergraduate degrees across its five schools.[182] In the 2010–2011 academic year, 1,161 bachelor of science (abbreviated SB) degrees were granted, the only type of undergraduate degree MIT now awards.[183][184] In the 2011 fall term, among students who had designated a major, the School of Engineering was the most popular division, enrolling 62.7% of students in its 19 degree programs, followed by the School of Science (28.5%), School of Humanities, Arts, & Social Sciences (3.7%), Sloan School of Management (3.3%), and School of Architecture and Planning (1.8%). The largest undergraduate degree programs were in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (Course 6-2), Computer Science and Engineering (Course 6-3), Mechanical Engineering (Course 2), Physics (Course 8), and Mathematics (Course 18).[4]

All undergraduates are required to complete a core curriculum called the General Institute Requirements (GIRs).[185] The Science Requirement, generally completed during freshman year as prerequisites for classes in science and engineering majors, comprises two semesters of physics, two semesters of calculus, one semester of chemistry, and one semester of biology. There is a Laboratory Requirement, usually satisfied by an appropriate class in a course major. The Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (HASS) Requirement consists of eight semesters of classes in the humanities, arts, and social sciences, including at least one semester from each division as well as the courses required for a designated concentration in a HASS division. Under the Communication Requirement, two of the HASS classes, plus two of the classes taken in the designated major must be "communication-intensive",[186] including "substantial instruction and practice in oral presentation".[187] Finally, all students are required to complete a swimming test; non-varsity athletes must also take four quarters of physical education classes.[185]

Most classes rely on a combination of lectures, recitations led by graduate students, weekly problem sets ("p-sets"), and tests. Although keeping up with the pace and difficulty of MIT coursework has been compared to "drinking from a fire hose",[188][189] the freshmen retention rate at MIT is similar to that at other national research universities.[190] The "pass/no-record" grading system relieves some of the pressure for first-year undergraduates. For each class taken in the fall term, freshmen transcripts will either report only that the class was passed, or otherwise not have any record of it. In the spring term, passing grades (A, B, C) appear on the transcript while non-passing grades are again not recorded.[191] (Grading had previously been "pass/no record" all freshman year, but was amended for the Class of 2006 to prevent students from gaming the system by completing required major classes in their freshman year.[192]) Also, freshmen may choose to join alternative learning communities, such as Experimental Study Group, Concourse, or Terrascope.[191]

In 1969, Margaret MacVicar founded the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) to enable undergraduates to collaborate directly with faculty members and researchers. Students join or initiate research projects ("UROPs") for academic credit, pay, or on a volunteer basis through postings on the UROP website or by contacting faculty members directly.[193] A substantial majority of undergraduates participate.[194][195] Students often become published, file patent applications, and/or launch start-up companies based upon their experience in UROPs.[196][197]

In 1970, the then-Dean of Institute Relations, Benson R. Snyder, published The Hidden Curriculum, arguing that education at MIT was often slighted in favor of following a set of unwritten expectations, and that graduating with good grades was more often the product of figuring out the system rather than a solid education. The successful student, according to Snyder, was the one who was able to discern which of the formal requirements were to be ignored in favor of which unstated norms. For example, organized student groups had compiled "course bibles", collections of problem-set and examination questions and answers to be used as references for later students. This sort of gamesmanship, Snyder argued, hindered the development of a creative intellect and contributed to student discontent and unrest.[198][199]

Graduate program

MIT's graduate program has high coexistence with the undergraduate program and offers a comprehensive doctoral program with degrees in the humanities, social sciences, and STEM fields as well as professional degrees.[166] The Institute offers graduate programs leading to academic degrees such as the Master of Science (SM), various Engineer's Degrees, Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), and Doctor of Science (ScD); professional degrees such as Master of Architecture (MArch),[200] Master of Business Administration (MBA),[201] Master of City Planning (MCP),[202] Master of Engineering (MEng),[203] and Master of Finance (MFin); and interdisciplinary graduate programs such as the MD/PhD (with Harvard Medical School).[204][205] Admission to graduate programs is decentralized; applicants apply directly to the department or degree program. More than 90% of doctoral students are supported by fellowships, research assistantships, or teaching assistantships.[206] MIT awarded 1,547 master's degrees and 609 doctoral degrees in the 2010–11 academic year.[183] In the 2011 fall term, the School of Engineering was the most popular academic division, enrolling 45.0% of graduate students, followed by the Sloan School of Management (19%), School of Science (16.9%), School of Architecture and Planning (9.2%), Whitaker College of Health Sciences (5.1%),[i] and School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (4.7%). The largest graduate degree programs were the Sloan MBA, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and Mechanical Engineering.[4]

Libraries, collections, and museums

The MIT library system consists of five subject libraries: Barker (Engineering), Dewey (Economics), Hayden (Humanities and Science), Lewis (Music), and Rotch (Arts and Architecture). There are also various specialized libraries and archives. The libraries contain more than 2.9 million printed volumes, 2.4 million microforms, 49,000 print or electronic journal subscriptions, and 670 reference databases. The past decade has seen a trend of increased focus on digital over print resources in the libraries.[207] Notable collections include the Lewis Music Library with an emphasis on 20th and 21st-century music and electronic music,[208] the List Visual Arts Center's rotating exhibitions of contemporary art,[209] and the Compton Gallery's cross-disciplinary exhibitions.[210] MIT allocates a percentage of the budget for all new construction and renovation to commission and support its extensive public art and outdoor sculpture collection.[211][212] The MIT Museum was founded in 1971 and collects, preserves, and exhibits artifacts significant to the life and history of MIT as well as collaborating with the nearby Museum of Science.[213]

Research

MIT was elected to the Association of American Universities in 1934 and remains a research university with a very high level of research activity;[41][166] research expenditures totaled $718.2 million in 2009.[16] The federal government was the largest source of sponsored research, with the Department of Health and Human Services granting $255.9 million, Department of Defense $97.5 million, Department of Energy $65.8 million, National Science Foundation $61.4 million, and NASA $27.4 million.[16] MIT employs approximately 1300 researchers in addition to faculty.[214] In 2011, MIT faculty and researchers disclosed 632 inventions, were issued 153 patents, earned $85.4 million in cash income, and received $69.6 million in royalties.[215] Through programs like the Deshpande Center, MIT faculty leverage their research and discoveries into multi-million-dollar commercial ventures.[216]

In electronics, magnetic core memory, radar, single electron transistors, and inertial guidance controls were invented or substantially developed by MIT researchers.[217][218] Harold Eugene Edgerton was a pioneer in high speed photography.[219] Claude E. Shannon developed much of modern information theory and discovered the application of Boolean logic to digital circuit design theory.[220] In the domain of computer science, MIT faculty and researchers made fundamental contributions to cybernetics, artificial intelligence, computer languages, machine learning, robotics, and cryptography.[218][221] At least nine Turing Award laureates and seven recipients of the Draper Prize in engineering have been or are currently associated with MIT.[222][223]

Current and previous physics faculty have won eight Nobel Prizes,[224] four Dirac Medals,[225] and three Wolf Prizes predominantly for their contributions to subatomic and quantum theory.[226] Members of the chemistry department have been awarded three Nobel Prizes and one Wolf Prize for the discovery of novel syntheses and methods.[224] MIT biologists have been awarded six Nobel Prizes for their contributions to genetics, immunology, oncology, and molecular biology.[224] Professor Eric Lander was one of the principal leaders of the Human Genome Project.[227][228] Positronium atoms,[229] synthetic penicillin,[230] synthetic self-replicating molecules,[231] and the genetic bases for Lou Gehrig's disease and Huntington's disease were first discovered at MIT.[232] Jerome Lettvin transformed the study of cognitive science with his paper "What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain".[233]

In the domain of humanities, arts, and social sciences, MIT economists have been awarded five Nobel Prizes and nine John Bates Clark Medals.[224][234] Linguists Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle authored seminal texts on generative grammar and phonology.[235][236] The MIT Media Lab, founded in 1985 within the School of Architecture and Planning and known for its unconventional research,[237][238] has been home to influential researchers such as constructivist educator and Logo creator Seymour Papert.[239]

Spanning many of the above fields, MacArthur Fellowships (the so-called "Genius Grants") have been awarded to 38 people associated with MIT.[240] Four Pulitzer Prize winning writers currently work at or have retired from MIT.[241] Four current or former faculty are members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[242]

Given MIT's prominence, allegations of research misconduct or improprieties have received substantial press coverage. Professor David Baltimore, a Nobel Laureate, became embroiled in a misconduct investigation starting in 1986 that led to Congressional hearings in 1991.[243][244] Professor Ted Postol has accused the MIT administration since 2000 of attempting to whitewash potential research misconduct at the Lincoln Lab facility involving a ballistic missile defense test, though a final investigation into the matter has not been completed.[245][246] Associate Professor Luk Van Parijs was dismissed in 2005 following allegations of scientific misconduct and found guilty of the same by the United States Office of Research Integrity in 2009.[247][248]

Traditions and student activities

The faculty and student body highly value meritocracy and technical proficiency.[249][250] MIT has never awarded an honorary degree, nor does it award athletic scholarships, ad eundem degrees, or Latin honors upon graduation.[251] However, MIT has twice awarded honorary professorships: to Winston Churchill in 1949 and Salman Rushdie in 1993.[252]

Many upperclass students and alumni wear a large, heavy, distinctive class ring known as the "Brass Rat".[253][254] Originally created in 1929, the ring's official name is the "Standard Technology Ring."[255] The undergraduate ring design (a separate graduate student version exists as well) varies slightly from year to year to reflect the unique character of the MIT experience for that class, but always features a three-piece design, with the MIT seal and the class year each appearing on a separate face, flanking a large rectangular bezel bearing an image of a beaver.[253] The initialism IHTFP, representing the informal school motto "I Hate This Fucking Place" and jocularly euphemized as "I Have Truly Found Paradise," "Institute Has The Finest Professors," "It's Hard to Fondle Penguins," and other variations, has occasionally been featured on the ring given its historical prominence in student culture.[256]

Activities

MIT has over 380 recognized student activity groups,[257] including a campus radio station, The Tech student newspaper, an annual entrepreneurship competition, and weekly screenings of popular films by the Lecture Series Committee. Less traditional activities include the "world's largest open-shelf collection of science fiction" in English, a model railroad club, and a vibrant folk dance scene. Students, faculty, and staff are involved in over 50 educational outreach and public service programs through the MIT Museum, Edgerton Center, and MIT Public Service Center.[258]

The Independent Activities Period is a four-week long "term" offering hundreds of optional classes, lectures, demonstrations, and other activities throughout the month of January between the Fall and Spring semesters. Some of the most popular recurring IAP activities are the 6.270, 6.370, and MasLab competitions,[259] the annual "mystery hunt",[260] and Charm School.[261][262] More than 250 students pursue externships annually at companies in the US and abroad.[263][264].

Many MIT students also engage in "hacking," which encompasses both the physical exploration of areas that are generally off-limits (such as rooftops and steam tunnels), as well as elaborate practical jokes.[265][266] Recent high-profile hacks have included the theft of Caltech's cannon,[267] reconstructing a Wright Flyer atop the Great Dome,[268] and adorning the John Harvard statue with the Master Chief's Spartan Helmet.[269]

Athletics

The student athletics program offers 33 varsity-level sports, which makes it one of the largest programs in the United States.[270][271] MIT participates in the NCAA's Division III, the New England Women's and Men's Athletic Conference, the New England Football Conference, the Pilgrim League for men's lacrosse and NCAA's Division I Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges (EARC) for crew. In April 2009, budget cuts lead to MIT eliminating eight of its 41 sports, including the mixed men’s and women’s teams in alpine skiing and pistol; separate teams for men and women in ice hockey and gymnastics; and men’s programs in golf and wrestling.[272][273][274]

The Institute's sports teams are called the Engineers, their mascot since 1914 being a beaver, "nature's engineer." Lester Gardner, a member of the Class of 1898, provided the following justification:

The beaver not only typifies the Tech, but his habits are particularly our own. The beaver is noted for his engineering and mechanical skills and habits of industry. His habits are nocturnal. He does his best work in the dark.[275]

MIT fielded several dominant intercollegiate Tiddlywinks teams through 1980, winning national and world championships.[276] MIT has produced 128 Academic All-Americans, the third largest membership in the country for any division and the highest number of members for Division III.[270]

The Zesiger sports and fitness center (Z-Center) which opened in 2002, significantly expanded the capacity and quality of MIT's athletics, physical education, and recreation offerings to 10 buildings and 26 acres (110,000 m2) of playing fields. The 124,000-square-foot (11,500 m2) facility features an Olympic-class swimming pool, international-scale squash courts, and a two-story fitness center.[270]

People

Students

| Undergraduate | Graduate | |

|---|---|---|

| Caucasian American | 34% | 40.8% |

| Asian American | 30% | 9.4% |

| Hispanic American | 15% | 3.3% |

| African American | 10% | 2.1% |

| Native American | 1.0% | 0.4% |

| Other/International | 8% | 44.0% |

MIT enrolled 4,384 undergraduates and 6,510 graduate students in 2011–2012.[4] Women constituted 45 percent of undergraduate students.[4][279] Undergraduate and graduate students are drawn from all 50 states as well as 115 foreign countries in the 2011–2012 school year.[280]

MIT received 17,909 applications for admission to the undergraduate Class of 2015; 1,742 were admitted (9.7 percent) and 1128 enrolled (64.8 percent).[118] 19,446 applications were received for graduate and advanced degree program across all departments; 2,991 were admitted (15.4 percent) and 1,880 enrolled (62.8 percent).[281] The interquartile range on the SAT was 2030–2320 and 95 percent of students ranked in the top tenth of their high school graduating class.[118] 97 percent of the Class of 2012 returned as sophomores; 82.3 percent of the Class of 2007 graduated within 4 years, and 91.3 percent (92 percent of the men and 96 percent of the women) graduated within 6 years.[118][282]

Undergraduate tuition and fees total $40,732 and annual expenses are estimated at $52,507 as of 2012. 62 percent of students received need-based financial aid in the form of scholarships and grants from federal, state, institutional, and external sources averaging $38,964 per student.[283] MIT awarded $87.6 million in scholarships and grants, the vast majority ($73.4 million) coming from institutional support.[118] The annual increase in expenses has led to a student tradition (dating back to the 1960s) of tongue-in-cheek "tuition riots".[284]

MIT has been nominally coeducational since admitting Ellen Swallow Richards in 1870. Richards also became the first female member of MIT's faculty, specializing in sanitary chemistry.[285] Female students remained a very small minority (less than 3 percent) prior to the completion of the first wing of a women's dormitory, McCormick Hall, in 1962.[286][287] Between 1993 and 2009, the proportion of women rose from 34 percent to 45 percent of undergraduates and from 20 percent to 31 percent of graduate students.[4][288] Women currently outnumber men in Biology, Brain & Cognitive Sciences, Architecture, Urban Planning, and Biological Engineering.[4][279]

A number of student deaths in the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in considerable media attention to MIT's culture and student life.[289][290] After the alcohol-related death of Scott Krueger in September 1997 as a new member at the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity,[291] MIT began requiring all freshmen to live in the dormitory system.[291][292] The 2000 suicide of MIT undergraduate Elizabeth Shin drew attention to suicides at MIT and created a controversy over whether MIT had an unusually high suicide rate.[293][294] In late 2001 a task force's recommended improvements in student mental health services were implemented,[295][296] including expanding staff and operating hours at the mental health center.[297] These and later cases were significant as well because they sought to prove the negligence and liability of university administrators in loco parentis.[293]

Faculty

MIT has 1,018 faculty members, of whom 217 are women.[3] Faculty are responsible for lecturing classes, advising both graduate and undergraduate students, and sitting on academic committees, as well as conducting original research. Between 1964 and 2009, a total of seventeen faculty and staff members affiliated with MIT were awarded Nobel Prizes (fourteen during the last quarter century, thirteen the last 25 years).[298] MIT faculty members past or present have won a total of twenty-seven Nobel Prizes, the majority in Economics or Physics.[299] Among current faculty and teaching staff, there are eighty Guggenheim Fellows, six Fulbright Scholars, and twenty-nine MacArthur Fellows.[3] Faculty members who have made extraordinary contributions to their research field as well as the MIT community are granted appointments as Institute Professors for the remainder of their tenures.

A 1998 MIT study concluded that a systemic bias against female faculty existed in its college of science,[300] although the study's methods were controversial.[301][302] Since the study, though, women have headed departments within the Schools of Science and Engineering, and MIT has appointed several female vice presidents, although allegations of sexism continue to be made.[303] Susan Hockfield, a molecular neurobiologist, was MIT's president from 2004 to 2012 and was the first woman to hold the post.[138]

Tenure outcomes have vaulted MIT into the national spotlight on several occasions. The 1984 dismissal of David F. Noble, a historian of technology, became a cause célèbre about the extent to which academics are granted freedom of speech after he published several books and papers critical of MIT's and other research universities' reliance upon financial support from corporations and the military.[304] Former materials science professor Gretchen Kalonji sued MIT in 1994 alleging that she was denied tenure because of sexual discrimination.[303][305] In 1997, the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination issued a probable cause finding supporting James Jennings' allegations of racial discrimination after a senior faculty search committee in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning did not offer him reciprocal tenure.[306] In 2006–2007, MIT's denial of tenure to African-American biological engineering professor James Sherley reignited accusations of racism in the tenure process, eventually leading to a protracted public dispute with the administration, a brief hunger strike, and the resignation of Professor Frank L. Douglas in protest.[307][308]

MIT faculty members have often been recruited to lead other colleges and universities; former Provost Robert A. Brown is President of Boston University, former Provost Mark Wrighton is Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis, former Associate Provost Alice Gast is president of Lehigh University, former Dean of the School of Science Robert J. Birgeneau is the Chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, and former professor David Baltimore had been President of Caltech. In addition, faculty members have been recruited to lead governmental agencies; for example, former professor Marcia McNutt is the director of the United States Geological Survey,[309] urban studies professor Xavier de Souza Briggs is currently the associate director of the White House Office of Management and Budget,[310] and biology professor Eric Lander is a co-chair of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.[311]

Alumni

Many of MIT's over 120,000 alumni have had considerable success in scientific research, public service, education, and business. As of 2011, twenty-four MIT alumni have won the Nobel Prize, forty-four have been selected as Rhodes Scholars, and fifty-five have been selected as Marshall Scholars.[312]

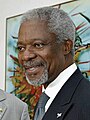

Alumni in American politics and public service include Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke, MA-1 Representative John Olver, Chief Economic Adviser of India Raghuram Rajan, CA-13 Representative Pete Stark, former National Economic Council chairman Lawrence H. Summers, and former Council of Economic Advisors chairwoman Christina Romer. MIT alumni in international politics include Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi, physicist Richard Feynman, former British Foreign Minister David Miliband, former Greek Prime Minister Lucas Papademos, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Ahmed Chalabi.

MIT alumni founded or co-founded many notable companies, such as Intel, McDonnell Douglas, Texas Instruments, 3Com, Qualcomm, Bose, Raytheon, Koch Industries, Rockwell International, Genentech, Dropbox, and Campbell Soup. According to the British newspaper, The Guardian, "a survey of living MIT alumni found that they have formed 25,800 companies, employing more than three million people including about a quarter of the workforce of Silicon Valley. Those firms between them generate global revenues of about $1.9tn (£1.2tn) a year. If MIT was a country, it would have the 11th highest GDP of any nation in the world."[313]

Prominent institutions of higher education have been led by MIT alumni, including the University of California system, Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, Carnegie Mellon University, Tufts University, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), Northeastern University, Lahore University of Management Sciences, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Tecnológico de Monterrey, Purdue University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Quaid-e-Azam University.

More than one third of the United States' manned spaceflights have included MIT-educated astronauts (among them Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin), more than any university excluding the United States service academies.[314]

Noted alumni in non-scientific fields include author Hugh Lofting,[315] sculptor Daniel Chester French, Boston guitarist Tom Scholz, The New York Times columnist and Nobel Prize Winning economist Paul Krugman, The Bell Curve author Charles Murray, United States Supreme Court building architect Cass Gilbert, Pritzker Prize-winning architects I.M. Pei and Gordon Bunshaft.

-

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin, ScD 1963 (Aero & Astro)

-

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, SM 1972 (Management)

-

Federal Reserve Bank Chairman Ben Bernanke, PhD 1979 (Economics)

-

Physicist Nobel laureate Richard Feynman, SB 1939 (Physics)

-

Economics Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, PhD 1977 (Economics)

-

Biologist, suffragist, philanthropist Katherine Dexter McCormick (left), SB 1904 (Biology)

-

Astronaut physicist Ronald McNair, PhD 1976 (Physics)

-

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, SB 1975 (Architecture), SM 1976 (Management)

-

Architect I. M. Pei, BArch 1940 (Architecture)

-

CEO of General Motors Alfred P. Sloan, SB 1895 (Electrical Engineering)

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ "We looked up and discussed many colors. We all desired cardinal red; it has stood for a thousand years on land and sea in England's emblem; it makes one-half of the stripes on America's flag; it has always stirred the heart and mind of man; it stands for 'red blood' and all that 'red blood' stands for in life. But we were not unanimous for the gray; some wanted blue, I recall. But it (the gray) seemed to me to stand for those quiet virtues of modesty and persistency and gentleness, which appealed to my mind as powerful; and I have come to believe, from observation and experience, to really be the most lasting influences in life and history....We recommended 'cardinal and steel gray.'" (Alfred T. Waite, Chairman of School Color Committee, Class of 1879)[7]

- ^ In 1863, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts separately founded under the same act the Massachusetts Agricultural College, which later became the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Besides MIT, the other privately owned land-grant institution is Cornell University.

- ^ A comparison of today's maps and older maps reveals that much of MIT's current campus is located on what was once the Charles River.[37] See also History of Boston.

- ^ The friezes of the marble-clad buildings surrounding Killian Court are carved in large Roman letters with the names of Aristotle, Newton, Pasteur, Lavoisier, Faraday, Archimedes, da Vinci, Darwin, and Copernicus; each of these names is surmounted by a cluster of appropriately related names in smaller letters. Lavoisier, for example, is placed in the company of Boyle, Cavendish, Priestley, Dalton, Gay Lussac, Berzelius, Woehler, Liebig, Bunsen, Mendelejeff [sic], Perkin, and van't Hoff.[104][105]

- ^ The Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology (HST) offers joint MD, MD-PhD, or Medical Engineering degrees in collaboration with Harvard Medical School.[134]

- ^ Vannevar Bush was the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development and general advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, James Rhyne Killian was Special Assistant for Science and Technology for Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Jerome Wiesner advised John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.[144]

- ^ MIT's Building 7 and Harvard's Johnston Gate, the traditional entrances to each school, are 1.72 miles (2.77 km) apart along Massachusetts Avenue.

- ^ Course numbers are sometimes presented in Roman numerals, e.g. "Course XVIII" for mathematics.[4] At least one MIT style guide frowns upon this usage.[181]

- ^ Figure includes 196 students working on Harvard degrees only.

Citations

- ^ "Symbols: Seal". MIT Graphic Identity. MIT. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ "MIT releases endowment figures for 2012". MIT News Office. MIT. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (2009, January). "MIT facts 2009: Faculty and staff". MIT Bulletin. 144 (4).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Enrollment Statistics". MIT Office of the Registrar. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "MIT Facts: The Campus". MIT. 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "Awards and Honors". Institutional Research, Office of the Provost. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ^ "Symbols: Colors". MIT Graphic Identity. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Symbols: Mascot". MIT Graphic Identity. MIT. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ Angulo, A.J. William Barton Rogers and the Idea of MIT. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 0-8018-9033-0.

- ^ a b c d Lecuyer, Christophe (1992). "The making of a science based technological university: Karl Compton, James Killian, and the reform of MIT, 1930–1957". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 23 (1): 153–180.

- ^ a b "MIT Facts 2012: MIT at a Glance". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2012.

- ^ "MIT Rhodes Scholars". Institutional Research, Office of the Provost. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Ericka Chickowski (September 20, 2010). "Gurus and Grads". Entrepreneur.

- ^ "Kauffman Foundation study finds MIT alumni companies generate billions for regional economies". MIT News Office. February 17, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "MIT releases 2010 endowment figures". September 27, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Research at MIT". MIT Facts. MIT. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Top 10 Worst Team Names". Time magazine. July 4, 2011.

- ^ "Charter of the MIT Corporation". Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Kneeland, Samuel (1859). "Committee Report:Conservatory of Art and Science" (PDF). Massachusetts House of Representatives, House No. 260.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "MIT Timeline". MIT History. MIT Institute Archives. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ "Acts and Resolves of the General Court Relating to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology" (PDF). MIT History. MIT Institute Archives. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "MIT Facts 2012: Origins and Leadership". MIT Facts. MIT. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Rogers, William (1861). "Objects and Plan of an Institute of Technology: including a Society of Arts, a Museum of Arts, and a School of Industrial Science; proposed to be established in Boston" (PDF). The Committee of Associated Institutions of Science and Arts.

- ^ Lewis 1949, p. 8.

- ^ "Letter from William Barton Rogers to His Brother Henry". Institute Archives, MIT. March 13, 1846. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Angulo, A.J. "The Initial Reception of MIT, 1860s–1880s". In Geiger, Roger L. (ed.). Perspectives on the History of Higher Education. pp. 1–28.

- ^ Andrews, Elizabeth (2000). "William Barton Rogers: MIT's Visionary Founder". MIT Archives.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stratton, Julius Adams; Mannix, Loretta H. (2005). "The Land-Grant Act of 1862". Mind and Hand: The Birth of MIT. MIT Press. pp. 251–276. ISBN 0-262-19524-0.

- ^ a b Prescott, Samuel C (1954). When M.I.T. Was "Boston Tech", 1861–1916. MIT Press.

- ^ a b Dunbar, Charles F. (1897). "The Career of Francis Amasa Walker". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 11 (4): 446–447.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Explore campus, visit Boston, and find out if MIT fits you to a tea". December 16, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ Munroe, James P. (1923). A Life of Francis Amasa Walker. New York: Henry Holt & Company. pp. 233, 382.

- ^ Lewis 1949, p. 12.

- ^ "Alumni Petition Opposing MIT-Harvard Merger, 1904–05". Institute Archives, MIT. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Students hope 'Eastman moment' proves lucky as they head into final exams". MIT News Office. May 22, 2002. Retrieved 12 Mary 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Souvenir Program, Dedication of Cambridge Campus, 1916". Object of the Month. MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Middlesex Canal (Massachusetts) map, 1852 (Map). J. B. Shields. 1852. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Freeman's 1912 Design for the "New Technology"". Object of the Month. MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Lewis 1949, p. 13.

- ^ Geiger, Roger L. (2004). To advance knowledge: the growth of American research universities, 1900–1940. pp. 13–15, 179–9. ISBN 0-19-503803-7.

- ^ a b "Member Institutions and Years of Admission". Association of American Universities. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ Lewis 1949, p. 113.

- ^ Bourzac, Katherine, "Rethinking an MIT Education: The faculty reconsiders the General Institute Requirements", Technology Review, Monday, March 12, 2007

- ^ "History: School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences". MIT Archives. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ "History: Sloan School of Management". MIT Archives. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Howard Wesley (2001). Holding the Center: Memoirs of a Life in Higher Education. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-60044-7.

- ^ a b Zachary, Gregg (1997). Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century. Free Press. pp. 248–249. ISBN 0-684-82821-9.

- ^ a b "MIT's Rad Lab". IEEE Global History Network. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ "Doc Draper & His Lab". History. The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Charles Draper: Gyroscopic Apparatus". Inventor of the Week. MIT School of Engineering. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Project Whirlwind". Object of the Month. MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Wartime Strobe: 1939–1945 – Harold "Doc" Edgerton". Retrieved November 28, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|h2=ignored (help) - ^ Bedi, Joyce (May 2010). "MIT and World War II: Ingredients for a Hot Spot of Invention" (PDF). Prototype. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Leslie, Stuart (1993). The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07959-1.

- ^ Lewis 1949, p. 49.

- ^ Lecuyer, 1992

- ^ a b Todd, Richard (May 18, 1969). "The 'Ins' and 'Outs' at M.I.T". The New York Times.

- ^ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (February 28, 1969). "A Policy of Protest". Time. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "Founding Document: 1968 MIT Faculty Statement". Union of Concerned Scientists, USA. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ Hechinger, Fred (November 9, 1969). "Tension Over Issue Of Defense Research". The New York Times.

- ^ Stevens, William (May 5, 1969). "MIT Curb on Secret Projects Reflects Growing Antimilitary Feeling Among Universities' Researchers". The New York Times.

- ^ Warsh, David (June 1, 1999). "A tribute to MIT's Howard Johnson". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

At a critical time in the late 1960s, Johnson stood up to the forces of campus rebellion at MIT. Many university presidents were destroyed by the troubles. Only Edward Levi, University of Chicago president, had comparable success guiding his institution to a position of greater strength and unity after the turmoil.

- ^ Lee, J.A.N. (1992). "The beginnings at MIT". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 14 (1): 18–54. doi:10.1109/85.145317. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Internet History". Computer History Museum. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S. "A Brief History of Hackerdom". Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ "The Media Lab – Retrospective". MIT Media Lab. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ "About W3C: History". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ "MIT OpenCourseWare". MIT. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ "Mission – One Laptop Per Child". One Laptop Per Child. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ "Massachusetts Space Grant Consortium". Massachusetts Space Grant Consortium. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ "MIT Sea Grant College Program". MIT Sea Grant College Program. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 4, 2009 suggested (help) - ^ Simha., O. R. (2003). MIT campus planning 1960–2000: An annotated chronology. MIT Press. pp. 120–149. ISBN 978-0-262-69294-6.

- ^ "MIT Facilities: In Development & Construction". MIT. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Bombardieri, Marcella (September 14, 2006). "MIT will accelerate its building boom: $750m expansion to add 4 facilities". The Boston Globe. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "About MITEI". MIT Energy Initiative. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Attwood, Rebecca (September 24, 2009). "Get it out in the open". Times Higher Education.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (April 4, 2001). "Auditing Classes at M.I.T., on the Web and Free". The New York Times.

- ^ Hafner, Katie (April 16, 2010). "An Open Mind". The New York Times.

- ^ Guttenplan, D.D. (November 1, 2010). "For Exposure, Universities Put Courses on the Web". The New York Times.

- ^ Lewin, Tamar (December 19, 2011). "M.I.T. Expands Its Free Online Courses". The New York Times.

- ^ "What is edX?". MIT News Office. May 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Campus". MIT Facts 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Durant, Elizabeth. "Smoot's Legacy: 50th anniversary of famous feat nears". Technology Review. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David (December 8, 2005). "The Measure of This Man Is in the Smoot; MIT's Human Yardstick Honored for Work". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Cambridge: Just the Facts (City Facts Brochure)". City of Cambridge. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ a b c "MIT Course Catalogue: Overview". MIT. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ "Building History and Numbering System". Mind and Hand Book, MIT. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "MIT Campus Subterranean Map" (PDF). MIT Department of Facilities. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Abel, David (March 30, 2000). "'Hackers' Skirt Security in Late-Night MIT Treks". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "MIT Course Catalogue". MIT. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "Loose Nukes: A Special Report". ABC News. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ^ "MIT Assures Community of Research Reactor Safety". MIT News Office. October 13, 2005. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- ^ "Supersonic Tunnel Open; Naval Laboratory for Aircraft Dedicated at M.I.T". The New York Times. December 2, 1949.

- ^ "Ship Test Tank for M.I.T.; Dr. Killian Announces Plant to Cost $500,000". The New York Times. February 6, 1949.

- ^ "MIT maps wireless users across campus". MIT. November 4, 2005. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ "Notice of Lodging of Consent Decree Pursuant to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act". Environmental Protection Agency. May 3, 2001. Retrieved July 16, 2008–.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sales, Robert (April 21, 2001). "MIT to create three new environmental projects as part of agreement with EPA". MIT News Office. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ "The Environment at MIT: Conservation". MIT. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ "Safety & Crime Report – Massachusetts Institute of Technology". American School Search. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "MIT Architecture: Welcome". MIT Department of Architecture. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Dillon, David (February 22, 2004). "Starchitecture on Campus". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 24, 2006.

- ^ Flint, Anthony (October 13, 2002). "At MIT, Going Boldly Where No Architect Has Gone Before". The Boston Globe.

- ^ a b Jarzombek, Mark (2004). Designing MIT: Bosworth's New Tech. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 50–51. ISBN 978-1-55553-619-0.

- ^ "Names of MIT Buildings". MIT Archives. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ^ "Names on Institute Buildings Lend Inspiration to Future Scientists". The Tech. December 22, 1922. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Campbell, Robert (March 2, 1986). "Colleges: More Than Ivy-Covered Halls". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Challenge to the Rectangle". TIME Magazine. June 29, 1953. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "Flagpole in the Square". TIME Magazine. August 22, 1960. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Campbell, Robert (May 20, 2001). "Architecture's Brand Names Come to Town". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Paul, James (April 9, 1989). "The Campuses of Cambridge, A City Unto Themselves". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lewis, Roger K. (November 24, 2007). "The Hubris of a Great Artist Can Be a Gift or a Curse". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "2010 361 Best College Rankings: Quality of Life: Campus Is Tiny, Unsightly, or Both". Princeton Review. 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ MIT Housing Office. "Undergraduate Residence Halls". Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Residential Life Live-in Staff". MIT. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ Yale Daily News Staff (2009). The Insider's Guide to the Colleges, 2010. St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 377–380. ISBN 0-312-57029-5.

- ^ MIT Housing Office. "Graduate residences for singles & families". MIT. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "MIT Facts: Housing". 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Common Data Set". Institutional Research, Office of the Provost, MIT. 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Undergraduate and Graduate Residence Halls, Fraternities, Sororities, and Independent Living Groups @ MIT" (PDF). MIT Residential Life. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ Zernike, Kate (August 27, 1998). "MIT rules freshmen to reside on campus". The Boston Globe. p. B1.

- ^ Russell, Jenna (August 25, 2002). "For First Time, MIT Assigns Freshmen to Campus Dorms". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "MIT Corporation". MIT Corporation. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation: Term Members". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation: Life Members". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation: Officers". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation: Ex Officio Members". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Bylaws of the MIT Corporation – Section 2: Members". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation – John Shepard Reed". The MIT Corporation. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Corporation elects new members, chair". MIT News Office. June 4, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "A Brief History and Workings of the Corporation". MIT Faculty Newsletter. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ "MIT Investment Management Company". MIT Investment Management Company. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ^ "2011 NACUBO Endowment Student" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers. 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "MIT Facts: Academic Schools and Departments, Divisions & Sections". 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Harvard-MIT HST Academics Overview". Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ^ Rafael L. Bras (2004–2005). "Reports to the President, Report of the Chair of the Faculty" (PDF). MIT. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "Reporting List". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ Bradt, Steve (May 16, 2012). "L. Rafael Reif selected as MIT's 17th president". MIT News.

- ^ a b "Susan Hockfield, President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Biography". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ "A Survey of New England: A Concentration of Talent". The Economist. August 8, 1987.

MIT for a long time... stood virtually alone as a university that embraced rather than shunned industry.

- ^ Roberts, Edward B. (1991). "An Environment for Entrepreneurs". MIT: Shaping the Future. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 0262631415.

The war made necessary the formation of new working coalitions... between these technologists and government officials. These changes were especially noteworthy at MIT.

- ^ "MIT ILP – About the ILP". Retrieved March 17, 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Kolata, Gina (December 19, 1990). "MIT Deal with Japan Stirs Fear on Competition". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ Booth, William (June 14, 1989). "MIT Criticized for Selling Research to Japanese Firms". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Nearly half of all US Presidential science advisers have had ties to the Institute". MIT News Office. May 2, 2001. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ "MIT Washington Office". MIT Washington Office. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ "Hunt Intense for Federal Research Funds: Universities Station Lobbyists in Washington". February 11, 2001.

- ^ Johnston, David (August 10, 1989). "Price-Fixing Inquiry at 20 Elite Colleges". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ Chira, Susan (March 13, 1991). "23 College Won't Pool Discal Data". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ DePalma, Anthony (May 23, 1991). "Ivy Universities Deny Price-Fixing But Agree to Avoid It in the Future". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ DePalma, Anthony (September 2, 1992). "MIT Ruled Guilty in Anti-Trust Case". The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ DePalma, Anthony (June 26, 1992). "Price-Fixing or Charity? Trial of M.I.T. Begins". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "Settlement allows cooperation on awarding financial-aid". MIT Tech Talk. 1994. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Honan, William (December 21, 1993). "MIT Suit Over Aid May Be Settled". The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "MIT Facts: Educational Partnerships". 2010. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ "Roberto Rocca Project". MIT. Retrieved Novembre 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives". MIT. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ "About Us". Technology Review. MIT. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Alumni Benefits". MIT Alumni Association. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "History – The MIT Press". MIT. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Massachusetts Institute of Technology". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ "MIT Facts: Accreditation". MIT. 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ "Roster of Institutions". Commission on Institutions of Higher Education, New England Association of Schools and Colleges. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ "Academic Calendar". Officer of the Registrar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Avery, Christopher; Glickman, Mark E.; Hoxby, Caroline M; Metrick, Andrew (2005). "A Revealed Preference Ranking of U.S. Colleges and Universities, NBER Working Paper No. W10803". National Bureau of Economic Research.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "2012 Parchment Top Choice College Rankings: All Colleges". Parchment Inc. Retrieved June 5, 2012.