Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis | |

|---|---|

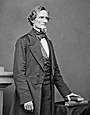

Jefferson Davis, c. 1862 | |

| President of the Confederate States of America | |

| In office February 18, 1861 – May 10, 1865 Provisional: February 18, 1861 – February 22, 1862 | |

| Vice President | Alexander Stephens |

| Preceded by | Office instituted |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| 23rd United States Secretary of War | |

| In office March 7, 1853 – March 4, 1857 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Charles Magill Conrad |

| Succeeded by | John B. Floyd |

| United States Senator from Mississippi | |

| In office August 10, 1847 – September 23, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | Jesse Speight |

| Succeeded by | John J. McRae |

| In office March 4, 1857 – January 21, 1861[1] | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Adams |

| Succeeded by | Adelbert Ames (1870) |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi's At-large district | |

| In office December 8, 1845 – June 1, 1846 | |

| Preceded by | Tilghman M. Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Henry T. Ellett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jefferson Finis Davis June 3, 1808 Christian County, Kentucky |

| Died | December 6, 1889 (aged 81) New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Resting place | Hollywood Cemetery Richmond, Virginia |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Knox Taylor (June–September 1835; her death) Varina Banks Howell (1845-1889; his death) |

| Alma mater | Jefferson College Transylvania University U.S.M.A. |

| Profession | Soldier, Politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | United States Army Mississippi Rifles |

| Years of service | 1828–1835, 1846–1847 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War |

Jefferson Finis Davis (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President of the Confederate States of America for its entire history, from 1861 to 1865. Davis was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane (Cook) Davis. After attending Transylvania University, Davis graduated from West Point and fought in the Mexican–American War as a colonel of a volunteer regiment. He served as the United States Secretary of War under Democratic President Franklin Pierce. Both before and after his time in the Pierce administration, he served as a Democratic U.S. Senator representing the State of Mississippi. As a senator, he argued against secession, but did agree that each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union.[2]

On February 9, 1861, after Davis resigned from the United States Senate, he was selected to be the provisional President of the Confederate States of America; he was elected without opposition to a six-year term that November. During his presidency, Davis took charge of the Confederate war plans but was unable to find a strategy to stop the larger, more powerful and better organized Union. His diplomatic efforts failed to gain recognition from any foreign country, and he paid little attention to the collapsing Confederate economy, printing more and more paper money to cover the war's expenses.

Historians have criticized Davis for being a much less effective war leader than his Union counterpart Abraham Lincoln, which they attribute to Davis being overbearing, controlling, and overly meddlesome, as well as being out of touch with public opinion, and lacking support from a political party (since the Confederacy had no political parties).[3] His preoccupation with detail, reluctance to delegate responsibility, lack of popular appeal, feuds with powerful state governors, inability to get along with people who disagreed with him, and neglect of civil matters in favor of military ones all worked against him.[4]

After Davis was captured on May 10, 1865, he was charged with treason. Although he was not tried, he was stripped of his eligibility to run for public office; Congress posthumously lifted this restriction in 1978, 89 years after his death.[5] While not disgraced, he was displaced in Southern affection after the war by the leading Confederate general Robert E. Lee. However, many Southerners empathized with his defiance, refusal to accept defeat, and resistance to Reconstruction. Over time, admiration for his pride and ideals made him a Civil War hero to many Southerners, and his legacy became part of the foundation of the postwar New South.[6] By the late 1880s, Davis began to encourage reconciliation, telling Southerners to be loyal to the Union.[7][8][9] He was aided in the last decade of his life by the generosity of Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, a wealthy widow. First she invited him to her plantation in 1877 near Biloxi, Mississippi at a time when he was ailing, and gave him a cottage to use for working on his memoir. She bequeathed Davis her plantation before her death in 1878, as well as additional funds for his support. This enabled him to live in some comfort with his wife until his death in 1889.

Early life and first military career

Davis was born on June 3, 1808 in Christian County, Kentucky, the last child of ten of Jane (née Cook) and Samuel Emory Davis. Both of Davis' paternal grandparents had immigrated to North America from the region of Snowdonia in the North of Wales; the rest of his ancestry can be traced to England.[citation needed] Davis' paternal grandfather, Evan, married Lydia Emory Williams. Samuel Emory Davis was born to them in 1756. Lydia had two sons from a previous marriage. Samuel served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, along with his two older half-brothers. In 1783, after the war, he married Jane Cook (also born in Christian County, in 1759 to William Cook and his wife Sarah Simpson). Samuel died on July 4, 1824, when Jefferson was 16 years old. Jane died on October 3, 1845.[10]

During Davis' youth, his family moved twice: in 1811 to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana and in 1812 to Wilkinson County, Mississippi. Three of Jefferson’s older brothers served during the War of 1812. In 1813 Davis began his education at the Wilkinson Academy, near the family cotton plantation in the small town of Woodville. Two years later, Davis entered the Catholic school of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory, a school operated by the Dominican Order in Washington County, Kentucky. At the time, he was the only Protestant student at the school. Davis went on to Jefferson College at Washington, Mississippi in 1818, and then to Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky in 1821.[11]

In 1824 Davis entered the United States Military Academy (West Point).[12] While at West Point, Davis was placed under house arrest for his role in the Eggnog Riot in Christmas 1826. He graduated 23rd in a class of 33 in June 1828.[13] Following graduation, Second Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Wisconsin. Davis was still in Mississippi during the Black Hawk War of 1832 but, at its conclusion, his colonel Zachary Taylor assigned him to escort the chief Black Hawk to prison. Davis made an effort to shield Black Hawk from curiosity seekers and the chief noted in his autobiography that Davis treated him "with much kindness" and showed empathy for Black Hawk's situation as a prisoner.[14]

Early career

Joseph Davis gave his brother 900 acres of land adjoining his property, where Davis eventually developed Brierfield Plantation. Davis began with one slave, James Pemberton. By early 1836, Davis had purchased 16 slaves. He held a total of 40 slaves by 1840 and 74 by 1845. Pemberton served as Davis' overseer, an unusual position for a slave in Mississippi.[15]

For eight years following Sarah's death, Davis was reclusive; he worshipped her memory. He studied government and history, and had private political discussions with his brother Joseph. In 1840 he attended a Democratic meeting in Vicksburg and, to his surprise, was chosen as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson. In 1842 Davis attended the Democratic convention, and in 1843 became a candidate for the state House of Representatives, losing his first election. In 1844, Davis was sent to the party convention for a third time, and his interest in politics deepened. He was selected as one of six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election and campaigned effectively throughout Mississippi for the Democratic candidate, James K. Polk[16][17]

Second marriage and family

That same year, Davis met Varina Banks Howell, then 17 years old, whom his brother Joseph had invited for the Christmas season at Hurricane plantation. She was the daughter of Margaret L. Kempe and William Burr Howell, and the granddaughter of the late New Jersey Governor Richard Howell and his wife Keziah. Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old widower Davis had asked Varina to marry him. They became engaged over her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics, and they married on February 26, 1845.

Jefferson and Varina Howell Davis had six children; three died before reaching adulthood. Margaret and Winnie survived Jefferson.

- Samuel Emory, born July 30, 1852, was named after his grandfather; he died June 30, 1854, of an undiagnosed disease.[18]

- Margaret Howell, born February 25, 1855.[19] Margaret was the only child of Jefferson and Varina to marry and raise a family. She married Joel Addison Hayes, Jr. (1848–1919), and they had five children. In the late 19th century, they moved from Memphis, Tennessee to Colorado Springs, Colorado. She died on July 18, 1909 at the age of 54.[20]

- Jefferson Davis, Jr., born January 16, 1857. He died of yellow fever at age 21 on October 16, 1878, during an epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley that caused 20,000 deaths.[21]

- Joseph Evan, born on April 18, 1859; died at five years old as the result of an accidental fall on April 30, 1864.[22]

- William Howell, born on December 6, 1861, and named for Varina's father; died of diphtheria on October 16, 1872.[23]

- Varina Anne "Winnie" Davis, born on June 27, 1864, several months after Joseph's death. She died on September 18, 1898, at age 34. She was unmarried as her parents had refused to let her marry into a northern abolitionist family.[24]

Davis was plagued with poor health for most of his life. In addition to bouts with malaria, battle wounds from fighting in the Mexican-American War, and a chronic eye infection that made it impossible for him to endure bright light, he also suffered from trigeminal neuralgia, a nerve disorder that causes severe pain in the face. It has been called one of the most painful ailments known to mankind.[25][26]

Second military career

In 1846 the Mexican-American War began. Davis resigned his house seat in June and raised a volunteer regiment, the Mississippi Rifles, becoming its colonel.[27] On July 21, 1846, they sailed from New Orleans for the Texas coast. Davis armed the regiment with the M1841 Mississippi Rifle and trained the regiment in its use, making it particularly effective in combat.[28] In September 1846 Davis participated in the successful siege of Monterrey.[29]

On February 22, 1847, Davis fought bravely at the Battle of Buena Vista and was shot in the foot, being carried to safety by Robert H. Chilton. In recognition of Davis' bravery and initiative, commanding general Zachary Taylor is reputed to have said, "My daughter, sir, was a better judge of men than I was."[12] On May 17, 1847, President James K. Polk offered Davis a Federal commission as a brigadier general and command of a brigade of militia. Davis declined the appointment arguing that the United States Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, and not to the Federal government of the United States.[30]

Return to politics

Senator

Because of his war service, Governor Brown of Mississippi appointed Davis to fill out the senate term of the late Jesse Speight. He took his seat on December 5, 1847, and was elected to serve the remainder of his term in January 1848.[31] The Smithsonian Institution appointed him a regent at the end of December 1847.[32]

In 1848 Senator Davis introduced the first of several proposed amendments to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; this one would annex most of northeastern Mexico and failed with a vote of 44 to 11.[33] Regarding Cuba, Davis declared that it "must be ours" to "increase the number of slaveholding constituencies."[34] He also was concerned about the security implications of a Spanish holding lying a few miles off the coast of Florida.[35]

A group of Cuban revolutionaries led by Narciso López intended to forcibly liberate Cuba from Spanish rule. In 1849, López visited Davis and asked him to lead his filibuster expedition to Cuba. He offered an immediate payment of $100,000,[n 1] plus the same amount when Cuba was liberated. Davis turned down the offer, stating that it was inconsistent with his duty as a senator. When asked to recommend someone else, Davis suggested Robert E. Lee, then an army major in Baltimore; López approached Lee, who also declined on the grounds of his duty.[37][38]

The senate made Davis chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs. When his term expired he was elected to the same seat (by the Mississippi legislature, as the constitution mandated at the time). He had not served a year when he resigned (in September 1851) to run for the governorship of Mississippi on the issue of the Compromise of 1850, which Davis opposed. He was defeated by fellow Senator Henry Stuart Foote by 999 votes.[39] Left without political office, Davis continued his political activity. He took part in a convention on states' rights, held at Jackson, Mississippi, in January 1852. In the weeks leading up to the presidential election of 1852, he campaigned in numerous Southern states for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce and William R. King.[40]

Secretary of War

Franklin Pierce won the presidential election, and in 1853 he made Davis his Secretary of War.[41] In this capacity, Davis gave Congress four annual reports (in December of each year), as well as an elaborate one (submitted on February 22, 1855) on various routes for the proposed Transcontinental Railroad. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona from Mexico. He also increased the size of the regular army from 11,000 to 15,000 and introduced general usage of the improved guns that he had used successfully during the Mexican–American War.[42]

The Pierce administration ended in 1857 with the loss of the Democratic nomination to James Buchanan. Davis' term was to end with Pierce's, so he ran successfully for the Senate, and re-entered it on March 4, 1857.[43]

Return to Senate

His renewed service in the senate was interrupted by an illness that threatened him with the loss of his left eye. Still nominally serving in the senate, Davis spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. On the Fourth of July, he delivered an anti-secessionist speech on board a ship near Boston. He again urged the preservation of the Union on October 11 in Faneuil Hall, Boston, and returned to the senate soon after.[44]

As Davis explained in his memoir The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, he believed that each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union. He counseled delay among his fellow Southerners, because he did not think that the North would permit the peaceable exercise of the right to secession. Having served as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, he also knew that the South lacked the military and naval resources necessary to defend itself if war were to break out. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, however, events accelerated. South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860, and Mississippi did so on January 9, 1861. Davis had expected this but waited until he received official notification; then on January 21, the day Davis called "the saddest day of my life",[45] he delivered a farewell address to the United States Senate, resigned and returned to Mississippi.[46]

President of the Confederate States of America

Anticipating a call for his services since Mississippi had seceded, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Governor Pettus saying, "Judge what Mississippi requires of me and place me accordingly."[47] On January 23, 1861, Pettus made Davis a major general of the Army of Mississippi.[12] On February 9, a constitutional convention at Montgomery, Alabama, considered Davis, Howell Cobb, Alexander Stephens, and Robert Toombs for the office of provisional president. Davis "was the champion of a slave society and embodied the values of the planter class, and thus was chosen provisional Confederate President by acclamation."[48] He was inaugurated on February 18, 1861.[49][50] He was chosen partly because he was a well-known and experienced moderate who had served in a president's cabinet. In meetings of his own Mississippi legislature, Davis had argued against secession; but when a majority of the delegates opposed him, he gave in.[51] Davis wanted to serve as a general in the Confederate States Army and not as the president, but accepted the role for which he had been chosen.[52]

On November 6, 1861, Davis was elected Confederate States President without opposition. He was inaugurated on February 22, 1862.

Several forts in Confederate territory remained in Union hands. Davis sent a commission to Washington with an offer to pay for any federal property on Southern soil, as well as the Southern portion of the national debt. Lincoln refused. Informal discussions did take place with Secretary of State William Seward through Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell, an Alabamian who had not yet resigned; Seward hinted that Fort Sumter would be evacuated, but nothing definite was said.[53]

On March 1, Davis appointed General P. G. T. Beauregard to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina, where state officials prepared to take possession of Fort Sumter; Beauregard was to prepare his forces but avoid an attack on the fort. When Lincoln moved to resupply the fort with food, Davis and his cabinet directed Beauregard to demand its surrender or else take possession by force. Major Anderson did not surrender. Beauregard bombarded the fort, and the Civil War began.[54]

When Virginia joined the Confederacy, Davis moved his government to Richmond in May 1861. He and his family took up his residence there at the White House of the Confederacy later that month.[55] Having served since February as the provisional president, Davis was elected to a full six-year term on November 6, 1861 and was inaugurated on February 22, 1862.[56]

In June 1862, in his most successful move, Davis assigned General Robert E. Lee to replace the wounded Joseph E. Johnston in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, the main Confederate Army in the Eastern Theater. That December he made a tour of Confederate armies in the west of the country. Davis had a very small circle of military advisers, and largely made the main strategic decisions on his own (or approved those suggested by Lee). Davis evaluated the Confederacy's national resources and weaknesses and decided that, in order to win its independence, the Confederacy would have to fight mostly on the strategic defensive. Davis maintained mostly a defensive outlook throughout the war, paying special attention to the defense of his national capital at Richmond. He attempted strategic offensives when he felt that military success would (a) shake Northern self-confidence and (b) strengthen the peace movements there. The campaigns met defeat at Antietam (1862) and Gettysburg (1863).[57]

Administration and Cabinet

As provisional president in 1861, Davis formed his first cabinet. Robert Toombs of Georgia was the first Secretary of State, and Christopher Memminger of South Carolina became Secretary of the Treasury. LeRoy Pope Walker of Alabama was made Secretary of War, after being recommended for this post by Clement Clay and William Yancey (both of whom declined to accept cabinet positions themselves). John Reagan of Texas became Postmaster General, and Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana became Attorney General. Although Stephen Mallory was not put forward by the delegation from his state of Florida, Davis insisted that he was the best man for the job of Secretary of the Navy, and he was eventually confirmed.[58]

Since the Confederacy was founded, among other things, on states’ rights, one important factor in Davis’ choice of cabinet members was representation from the various states. He depended partly upon recommendations from congressmen and other prominent people, and this helped maintain good relations between the executive and legislative branches. This also led to complaints as more states joined the Confederacy, however, because there were more states than cabinet positions.[59]

Once the war began, there were frequent changes to the cabinet. Robert Hunter of Virginia replaced Toombs as Secretary of State on July 25, 1861. On September 17, Walker resigned as Secretary of War; Benjamin left the Attorney General position replace Walker, and Thomas Bragg of North Carolina (brother of General Braxton Bragg) took Benjamin’s place as Attorney General.[60]

Following the November 1861 election, Davis announced the permanent cabinet in March 1862. Benjamin moved again, to Secretary of State; George W. Randolph of Virginia had been made the Secretary of War. Mallory continued as Secretary of the Navy and Reagan as Postmaster General; both men kept their positions throughout the war. Memminger remained Secretary of the Treasury, while Thomas Hill Watts of Alabama was made Attorney General.[61]

In 1862, Randolph resigned from the War Department, and James Seddon of Virginia was appointed to replace him. In late 1863, Watts resigned as Attorney General to take office as the Governor of Alabama, and George Davis of North Carolina took his place. In 1864, Memminger withdrew from the Treasury post due to congressional opposition, and was replaced by George Trenholm of South Carolina. In 1865, congressional opposition likewise caused Seddon to withdraw, and he was replaced by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.[62]

Strategic failures

Most historians sharply criticize Davis for his flawed military strategy, his selection of friends for military commands, and his neglect of homefront crises.[63][64] Until late in the war, he resisted efforts to appoint a general-in-chief, essentially handling those duties himself. On January 31, 1865, Lee assumed this role, but it was far too late. Davis insisted on a strategy of trying to defend all Southern territory with ostensibly equal effort. This diluted the limited resources of the South and made it vulnerable to coordinated strategic thrusts by the Union into the vital Western Theater (e.g., the capture of New Orleans in early 1862). He made other controversial strategic choices, such as allowing Lee to invade the North in 1862 and 1863 while the Western armies were under very heavy pressure. Lee lost at Gettysburg, Vicksburg simultaneously fell, and the Union took control of the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy. At Vicksburg, the failure to coordinate multiple forces on both sides of the Mississippi River rested primarily on the his inability to create a harmonious departmental arrangement or to force such commanders as generals Edmund Kirby Smith, Earl Van Dorn, and Theophilus H. Holmes to work together.[65]

Davis has been faulted for poor coordination and management of his generals. This includes his reluctance to resolve a dispute between Leonidas Polk, a personal friend, and Braxton Bragg, who was defeated in important battles and distrusted by his subordinates.[66] He did relieve the cautious but capable Joseph E. Johnston and replaced him with the reckless John Bell Hood, resulting in the loss of Atlanta and the eventual loss of an army.[67]

Davis gave speeches to soldiers and politicians but largely ignored the common people and thereby failed to harness Confederate nationalism by directing the energies of the people into winning the war. More and more, the Plain Folk of the Old South resented the favoritism shown the rich and powerful.[68]

Barney speaks of "the heavy-handed intervention of the Confederate government." The Confederate income tax was higher than the Union one; and economic intervention, regulation, and state control of manpower, production and transport were much greater in the Confederacy than in the Union.[69] Davis did not use his presidential pulpit to rally the people with stirring rhetoric; he called instead for people to be fatalistic and to die for their new country.[70] Apart from two month-long trips across the country where he met a few hundred people, Davis stayed in Richmond where few people saw him; newspapers had limited circulation and most Confederates had little favorable information about him.[71]

In April 0001, food shortages led to rioting in Richmond, as poor people robbed and looted numerous stores for food until Davis cracked down and restored order.[72] Davis feuded bitterly with his vice president. Perhaps even more serious, he clashed with powerful state governors who used states' rights arguments to withhold their militia units from national service and otherwise blocked mobilization plans.[73]

Final days of the Confederacy

On April 3, 1865, with Union troops under Ulysses S. Grant poised to capture Richmond, Davis escaped for Danville, Virginia, together with the Confederate Cabinet, leaving on the Richmond and Danville Railroad. Lincoln sat in his Richmond office 40 hours after Davis' departure. On about April 12, he received Robert E. Lee's letter announcing surrender.[74] Davis issued his last official proclamation as president of the Confederacy, and then went south to Greensboro, North Carolina.[75]

After Lee's surrender, there was a public meeting in Shreveport, Louisiana, at which many speakers supported continuation of the war. Plans were developed for the Davis government to flee to Havana, Cuba. There, the leaders would regroup and head to the Confederate-controlled Trans-Mississippi area by way of the Rio Grande.[76] None of these plans were put into practice.

President Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time on May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia, and the Confederate government was officially dissolved. The meeting took place at the Heard house, the Georgia Branch Bank Building, with 14 officials present. Along with a hand-picked escort led by Given Campbell, Davis and his wife were captured on May 10, 1865, at Irwinville in Irwin County, Georgia.[77] They were intending to get to a point where they could sail to Europe. It was reported that Davis put his wife's overcoat over his shoulders while fleeing, inspiring caricatures that portrayed him as having disguised himself as a woman while trying to avoid capture.[78] Meanwhile, Davis' belongings continued on the train bound for Cedar Key, Florida. They were first hidden at Senator David Levy Yulee's plantation in Florida, then placed in the care of a railroad agent in Waldo. On June 15, 1865, Union soldiers seized Davis' personal baggage, together with some of the Confederate government's records, from the agent. A historical marker now stands at this site.[79][80][81]

Imprisonment

On May 19, 1865, Davis was imprisoned in a casemate at Fortress Monroe, on the coast of Virginia. He was placed in irons for three days. Davis was indicted for treason a year later. While in prison, Davis arranged to sell his Mississippi plantation to one of his former slaves, Ben Montgomery. While he was in prison, Pope Pius IX sent Davis a portrait inscribed with the Latin words, "Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis, et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus", which comes from Matthew 11:28 and translates as, "Come to me all ye who labor and are heavy burdened and I will give you rest, sayeth the Lord." A hand-woven crown of thorns associated with the portrait is often said to have been made by the Pope[82] but may have been woven by Davis's wife Varina Davis.[83]

Varina Davis with their young daughter Winnie were allowed to join Davis, and the family were eventually given an apartment in the officers' quarters.

Later years

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens of both Northern and Southern states, including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith. (Smith was a former member of the Secret Six who had supported John Brown). Davis visited Canada, Cuba and Europe in search of work.

In December 1868 the court rejected a motion to nullify the indictment, but the prosecution dropped the case in February 1869. That same year, Davis was hired as president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Memphis, Tennessee. He turned down the opportunity to become the first president of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M University).[84] For a time, he began to regain his income, but the insurance company went bankrupt in the Panic of 1873 and Davis had difficulty finding new work.

During Reconstruction, Davis publicly remained silent on his opinions; however, he privately expressed opinions that federal military rule and Republican authority over former Confederate states was unjustified. He considered "Yankee and Negroe" rule in the south oppressive. Davis held contemporary beliefs that Blacks were inferior to the White race. The historian William J. Cooper has stated that Davis believed in southern social order that included "a democratic white polity based firmly on dominance of a controlled and excluded black caste."[85]

In 1876, Davis promoted a society for the stimulation of US trade with South America. He visited England the next year. In 1877, Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, a wealthy widow who had heard of his difficulties, invited him to stay at her plantation of Beauvoir near Biloxi, Mississippi. She provided him with a cabin for his own use and helped him with his writing - through organization, dictation, editing, and encouragement.[86] Knowing she was severely ill, in 1878 Dorsey made over her will, leaving Beauvoir and her financial assets to Jefferson Davis and, in the case of his death, to his only surviving child, Winnie Davis.[87] Dorsey died in 1879, by when, both the Davises and Winnie were living at Beauvoir. Over the next two years, Davis completed The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881).[88]

Davis' reputation in the South was restored by the book and by his warm reception on his tour of the region in 1886 and 1887. In numerous stops, he attended "Lost Cause" ceremonies, where large crowds showered him with affection and local leaders presented emotional speeches honoring his sacrifices to the would-be nation. The Meriden Daily Journal stated that Davis, at a reception held in New Orleans in May 1887, urged southerners to be loyal to the nation. He said, "United you are now, and if the Union is ever to be broken, let the other side break it." Davis stated that men in the Confederacy had successfully fought for their own rights with inferior numbers during the Civil War and that the northern historians ignored this view.[8] Davis firmly believed that Confederate secession was constitutional. The former Confederate president was optimistic concerning American prosperity and the next generation.[89]

Davis completed A Short History of the Confederate States of America in October 1889. On November 6 he left Beauvoir to visit his plantation at Brierfield. On the steamboat trip upriver, he became ill; on the 13th he left Brierfield to return to New Orleans. Varina Davis, who had taken another boat to Brierfield, met him on the river, and he finally received some medical care. They arrived in New Orleans on the 16th, and he was taken to the home of Charles Erasmus Fenner, an Associate Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. Davis remained in bed but was stable for the next two weeks; however, he took a turn for the worse in early December. Just when he appeared to be improving, he lost consciousness on the evening of the 5th and died at age 81 at 12:45 a.m. on Friday, December 6, 1889, in the presence of several friends and with his hand in Varina's.[90][91]

His funeral was one of the largest in the South. Davis was first entombed at the Army of Northern Virginia tomb at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans. In 1893, Mrs. Davis decided to have his remains reinterred at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.[92] After the remains were exhumed in New Orleans, they lay for a day at Memorial Hall of the newly organized Louisiana Historical Association, with many mourners passing by the casket, including Governor Murphy J. Foster, Sr. The body was placed on a Louisville and Nashville Railroad car and transported to Richmond.[93] A continuous cortège, day and night, accompanied his body from New Orleans to Richmond.[94]

Legacy

Numerous memorials were created to Jefferson Davis. Examples include the 351-foot (107 m) concrete obelisk located at the Jefferson Davis State Historic Site in Fairview, Christian County, Kentucky, marking his birthplace. Construction of the monument began in 1917 and finished in 1924.[95]

The Jefferson Davis Presidential Library was established at Beauvoir Plantation, the white-columned Biloxi mansion that was Davis's final home, in 1998, after its use for some years as a Confederate Veterans Home. Dedicated in 1998, the house and library were damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The house reopened in 2008.[96] Bertram Hayes-Davis, Davis's great-great grandson, was recently hired as executive director of Beauvoir, which is owned by the Mississippi Division Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Based at Rice University in Houston, Texas, The Papers of Jefferson Davis is an editing project to publish documents related to Davis. Since the early 1960s, it has published 12 volumes, the first in 1971 and most recently in 2008; three more volumes are planned. The project has roughly 100,000 documents in its archives.[97]

The birthday of Jefferson Davis is commemorated in several states. His birthday, June 3, is celebrated in Florida,[98] Kentucky,[99] Louisiana[100] and Tennessee;[101] in Alabama, it is celebrated on the first Monday in June.[102] In Mississippi, the last Monday of May (Memorial Day) is celebrated as "National Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis' Birthday".[103] In Texas, "Confederate Heroes Day" is celebrated on January 19, the birthday of Robert E. Lee;[101] Jefferson Davis’ birthday had been officially celebrated on June 3 but was combined with Lee's birthday in 1973.[104]

In 1913, the United Daughters of the Confederacy conceived the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway, a transcontinental highway to be built through the South.[105] Portions of the highway's route in Virginia, Alabama and other states still bear the name of Jefferson Davis.[105] On September 20, 2011, the County Board of Arlington County, Virginia voted to change the name of "Old Jefferson Davis Highway" (the original route of the road in the County) after the chairman of the Board, Chris Zimmerman, who was originally from the Northeast, stated: "I have a problem with 'Jefferson Davis' ... There are aspects of our history I'm not particularly interested in celebrating. I don't believe Jefferson Davis has a historic connection to anything in Arlington. He wasn't from Virginia".[106]

Notes

References

- ^ Foote, Shelby (1958). The Civil War: A Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House. p. 3.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 230.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Wiley, Bell I. (1967). "Jefferson Davis: An Appraisal". Civil War Times Illustrated. 6 (1): 4–17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Restoration of Citizenship Rights to Jefferson F. Davis Statement on Signing S. J. Res. 16 into Law". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ Strawbridge, Wilm K. (2007). "A Monument Better Than Marble: Jefferson Davis and the New South". Journal of Mississippi History. 69 (4): 325–347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Collins 2005, p. 156.

- ^ a b "Jefferson Davis' Loyalty". The Meriden Daily Journal. May 14, 1887. p. 1.

- ^ "Jeff Davis Coming Around". New York Times. May 14, 1887. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 4–5

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 11–27.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, Holman (1978). "Jefferson Davis Before His Presidency". The Three Kentucky Presidents. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0246-4.

- ^ U.S. Military Academy, Register of Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy from March 16, 1802 to January 1, 1850. Compiled by Capt. George W. Cullum. West Point, N.Y.: 1850, p. 148.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 76. Cooper 2000, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 75-79. Davis 1991, p. 89.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 84–88, 98-100.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 242, 268.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 273.

- ^ "Margaret Howell Davis Hayes Chapter No. 2652". Colorado United Daughters of the Confederacy. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ Strode 1964, p. 436.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 480.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 595.

- ^ Strode 1964, pp. 527–528.

- ^ Potter, Robert (1994). Jefferson Davis: Confederate President. Steck-Vaughn Company. p. 74.

- ^ Allen 1999, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 157.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 164–167.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 188.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 12, 93.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 195.

- ^ Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821-1848. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 634–636.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1989). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Bantam Books. p. 104.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 210.

- ^ Williamson, Samuel H. (2011). Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present. MeasuringWorth.

- ^ Thomson, Janice E. (1996). Mercenaries, Pirates and Sovereigns. Princeton University Press. p. 121.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar (1912). The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Nashville, Tennessee: Press of Brandon Printing Company. p. 111. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Davis, Jefferson". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 80, 133–135.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 12, 171–172.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 3.

- ^ "Jefferson Davis' Farewell". United States Senate. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 322.

- ^ Joan E. Cashin, First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis's Civil War, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006, p.

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 402–403.

- ^ "Inaugural Address of President Davis". Montgomery, Alabama: Shorter and Reid, Printers. February 18, 1861. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 197–198.

- ^ "Jefferson Davis". Document. www.civilwarhome.com.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 361-2.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 337–340.

- ^ Strode 1959, pp. 90–94.

- ^ Dodd 1907, p. 263.

- ^ Dawson, Joseph G. III (2009). "Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy's "Offensive-Defensive" Strategy in the U.S. Civil War". Journal of Military History. 73 (2): 591–607.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Patrick 1944, p. 51.

- ^ Patrick 1944, pp. 49–50, 56.

- ^ Patrick 1944, p. 53.

- ^ Patrick 1944, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Patrick 1944, p. 57.

- ^ Beringer, Richard E., Hattaway, Herman, Jones, Archer, and Still, William N., Jr. (1986). Why the South Lost the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Woodworth, Steven E. (1990). Jefferson Davis and His Generals: The Failure of Confederate Command in the West. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- ^ Woodworth, Steven E. (1990). "Dismembering the Confederacy: Jefferson Davis and the Trans-Mississippi West". Military History of the Southwest. 20 (1): 1–22.

- ^ Woodworth, Jefferson Davis and His Generals, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Hattaway and Beringer 2002.

- ^ Escott 1978.

- ^ William L. Barney (2011). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 341.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 475, 496.

- ^ Andrews, J. Cutler (1966). "The Confederate Press and Public Morale". Journal of Southern History. 32.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 447, 480, 496.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 511.

- ^ Keegan, John (2009). The American Civil War: A Military History. Vintage Books. pp. 375–376. ISBN 978-0-307-27314-7.

- ^ Dodd 1907, pp. 353–357.

- ^ Winters, John D. (1963). The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 419. ISBN 0-8071-0834-0.

- ^ "Jefferson Davis Was Captured". USA.gov. 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Capture of Jefferson Davis". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ Boone, Floyd E. (1988). Florida Historical Markers & Sites: A Guide to More Than 700 Historic Sites. Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company. p. 15. ISBN 0-87201-558-0.

- ^ "Historical Markers in Alachua County, Florida — DICKISON AND HIS MEN / JEFFERSON DAVIS' BAGGAGE". Alachua County Historical Commission. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ "Historic Markers Across Florida — Dickison and his men / Jefferson Davis' baggage". Latitude 34 North. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ Strode 1964, p. 302.

- ^ Kevin Levin. "Update on Jefferson Davis's Crown of Thorns". Civil War Memory. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Strode 1964, pp. 402–404.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 574, 575, 602, 603.

- ^ Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, pp. 165-166

- ^ Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 166

- ^ Strode 1964, pp. 439–441, 448–449.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 658.

- ^ Cooper 2000, pp. 652–654.

- ^ Charles E. Fenner. "Eulogy of Robert E. Lee".

- ^ "Jefferson Finis Davis". Find a Grave. 2001. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ Urquhart, Kenneth Trist (March 21, 1959). "Seventy Years of the Louisiana Historical Association" (PDF). Alexandria, Louisiana: Louisiana Historical Association. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ Collins 2005.

- ^ "Jefferson Davis State Historic Site". Kentucky State Parks. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ "Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library". Mississippi Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ "The Papers of Jefferson Davis". Rice University. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ "The 2010 Florida Statutes (including Special Session A)". The Florida Legislature. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "State Public Holidays". World Web Technologies, Inc. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "Days of public rest, legal holidays, and half-holidays". The Louisiana State Legislature. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Memorial Day History". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "Official State of Alabama Calend". Alabama State Government. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "Mississippi Code of 1972 - SEC. 3-3-7. Legal holiday". LawNetCom, Inc. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "State holidays". Texas State Library. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Weingroff, Richard F. (April 7, 2011). "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration, United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ (1) "Old Jefferson Davis Highway to be Renamed "Long Bridge Drive"". Newsroom. Arlington County, Virginia government. September 21, 2011. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

(2) McCaffrey, Scott (September 28, 2011). "Road Renaming Proves Another Chance to Re-Fight the Civil War". Arlington Sun Gazette. Springfield, Virginia: Sun Gazette Newspapers. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Allen, Felicity (1999). Jefferson Davis: Unconquerable Heart. Columbia: The University of Missouri Press.

- Ballard, Michael B. (1986). Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Collins, Donald E. (2005). The Death and Resurrection of Jefferson Davis. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Cooper, William J. (2000). Jefferson Davis, American. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Cooper, William J. (2008). Jefferson Davis and the Civil War Era. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Current, Richard, et al. (1993). Encyclopedia of the Confederacy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Davis, William C. (1991). Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour. New York: HarperCollins.

- Dodd, William E. (1907). Jefferson Davis. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs and Company.

- Eaton, Clement (1977). Jefferson Davis. New York: The Free Press.

- Escott, Paul (1978). After Secession: Jefferson Davis and the Failure of Confederate Nationalism. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Hattaway, Herman and Beringer, Richard E. (2002). Jefferson Davis, Confederate President. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Neely Jr., Mark E. (1993). Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

- Patrick, Rembert W. (1944). Jefferson Davis and His Cabinet. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Rable, George C. (1994). The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Stoker, Donald, "There Was No Offensive-Defensive Confederate Strategy," Journal of Military History, 73 (April 2009), 571–90.

- Strode, Hudson (1955). Jefferson Davis, Volume I: American Patriot. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Strode, Hudson (1959). Jefferson Davis, Volume II: Confederate President. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Strode, Hudson (1964). Jefferson Davis, Volume III: Tragic Hero. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Swanson, James L. (2010). Bloody Crimes: The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln's Corpse. New York: HarperCollins.

- Thomas, Emory M. (1979). The Confederate Nation, 1861–1865. New York: Harper & Row.

Primary sources

- Davis, Jefferson (2003). Cooper, Jr., William J (ed.). Jefferson Davis: The Essential Writings.

- Davis, Jefferson (1881). The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

- Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1923). Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist: His Letters, Papers, and Speeches. Jackson: Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

- Monroe, Jr., Haskell M.; McIntosh, James T.; Crist, Lynda L., eds. (1971–2008). The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Louisiana State University Press.

External links

- Jefferson Davis in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Jefferson Davis's final resting place

- Booknotes interview with William Cooper on Jefferson Davis, American, April 8, 2001.

- Works by Jefferson Davis at Project Gutenberg

- United States Congress. "Jefferson Davis (id: D000113)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- 1808 births

- 1889 deaths

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- American people of English descent

- American people of Welsh descent

- American pro-slavery activists

- Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia)

- Burials at Metairie Cemetery

- Confederate States Army generals

- Confederate States of America political leaders

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- Heads of state of the United States

- Heads of state of unrecognized or largely unrecognized states

- Historians of the American Civil War

- Jefferson College (Mississippi) alumni

- Jefferson Davis family

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Mississippi

- Mississippi Democrats

- People from Christian County, Kentucky

- People of Mississippi in the American Civil War

- People of the Black Hawk War

- Recipients of American presidential pardons

- Transylvania University alumni

- United States Army officers

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States Secretaries of War

- United States Senators from Mississippi

- Zachary Taylor family

- Pierce administration cabinet members