Homo heidelbergensis

| Homo heidelbergensis Temporal range: Pleistocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Subtribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. heidelbergensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo heidelbergensis Schoetensack, 1908

| |

Homo heidelbergensis ("Heidelberg Man", named after the University of Heidelberg) is an extinct species of the genus Homo which may be[1] the direct ancestor of both Homo neanderthalensis in Europe and Homo sapiens.[2] The best evidence found for these hominins dates them between 600,000 and 400,000 years ago. H. heidelbergensis stone tool technology was very close to that of the Acheulean tools used by Homo erectus.

Morphology and interpretations

Both H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis are likely to be descended from the morphologically very similar Homo ergaster from Africa. But because H. heidelbergensis had a larger brain-case — with a typical cranial volume of 1100–1400 cm³ overlapping the 1350 cm³ average of modern humans — and had more advanced tools and behavior, it has been given a separate species classification. Male heidelbergensis averaged about 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m) tall and 136 lb (62 kg). Females averaged 5 ft 2 in (1.57 m) and 112 lb (51 kg).[3] A reconstruction of 27 complete human limb bones found in Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain) has helped to determine the height of H. heidelbergensis compared to Homo neanderthalensis, the conclusion was that most H. heidelbergensis averaged about 170 cm (5ft 7in) in height and were only slightly taller than neanderthals.[4] According to Lee R. Berger of the University of Witwatersrand, numerous fossil bones indicate some populations of Heidelbergensis were "giants" routinely over 2.13 m (7 ft) tall and inhabited South Africa between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago.[5]

Social behavior

Recent findings in a pit in Atapuerca (Spain) of 28 human skeletons suggest that H. heidelbergensis may have been the first species of the Homo genus to bury their dead.[6]

Some experts[7] believe that H. heidelbergensis, like its descendant H. neanderthalensis, acquired a primitive form of language. No forms of art or sophisticated artifacts other than stone tools have been uncovered, although red ochre, a mineral that can be used to create a red pigment which is useful as a paint, has been found at Terra Amata excavations in the south of France.

Language

The morphology of the outer and middle ear suggests they had an auditory sensitivity similar to modern humans and very different from chimpanzees. They were probably able to differentiate between many different sounds.[8] Dental wear analysis suggests they were as likely to be right-handed as modern people.[9]

H. heidelbergensis was a close relative (most probably a migratory descendant) of Homo ergaster. H. ergaster is thought to be the first hominin to vocalize[7] and that as H. heidelbergensis developed more sophisticated culture proceeded from this point.

Evidence of hunting

500,000 year-old hafted stone points used for hunting are reported from Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa, tested by way of use-wear replication.[10] This find could mean that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals inherited the stone-tipped spear, rather than developing the technology independently.[10]

Divergent evolution

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2012) |

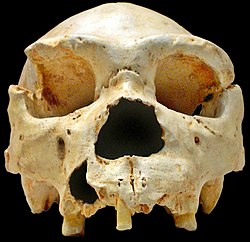

Because of the radiation of H. heidelbergensis out of Africa and into Europe, the two populations were mostly isolated during the Wolstonian Stage and Ipswichian Stage, the last of the prolonged Quaternary glacial periods. Neanderthals diverged from H. heidelbergensis probably some 300,000 years ago in Europe, during the Wolstonian Stage; H. sapiens probably diverged between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago in Africa. Such fossils as the Atapuerca skull and the Kabwe skull bear witness to the two branches of the H. heidelbergensis tree.[citation needed]

Homo neanderthalensis retained most of the features of H. heidelbergensis after its divergent evolution. Although shorter, Neanderthals were more robust, had large brow-ridges, a slightly protruding face, and lack of prominent chin. With the possible exception of Cro-Magnon Man, they also had a larger brain than all other hominins. Homo sapiens, on the other hand, have the smallest brows of any known hominin, are tall and lanky, and have a flat face with a protruding chin. H. sapiens have a larger brain than H. heidelbergensis, and a smaller brain than H. neanderthalensis, on average.[citation needed] To date, H. sapiens is the only known hominin with a high forehead, flat face, and thin, flat brows.[citation needed]

Some believe that H. heidelbergensis is a distinct species, and some that it is a cladistic ancestor to other Homo forms sometimes improperly linked to distinct species in terms of populational genetics.[citation needed]

Some scenarios of survival include:[citation needed]

- H. heidelbergensis > H. neanderthalensis

- H. heidelbergensis > H. rhodesiensis > H. sapiens idaltu > H. sapiens sapiens

Those supporting a multiregional origin of modern humans envision fertile reproduction between many evolutionary stages and homo walking,[11] or gene transfer between adjacent populations due to gene passage and spreading in successive generations.[citation needed]

Discovery

The first fossil discovery of this species was made on October 21, 1907, and came from Mauer where the workman Daniel Hartmann spotted a jaw in a sandpit. The jaw (Mauer 1) was in good condition except for the missing premolar teeth, which were eventually found near the jaw. The workman gave it to Professor Otto Schoetensack from the University of Heidelberg, who identified and named the fossil.

The next H. heidelbergensis remains were found in Steinheim an der Murr, Germany (the Steinheim Skull, 350kya); Arago, France (Arago 21); Petralona, Greece; Ciampate del Diavolo, Italy; Dali, Jinniushan and Maba, China.

Boxgrove Man

In 1994 British scientists unearthed a lower hominin tibia bone a few miles away from the English Channel, along with hundreds of ancient hand axes, at the Boxgrove Quarry site. This partial leg bone is dated to between 478,000 and 524,000 years old. Several H. heidelbergensis teeth were also found in subsequent seasons. H. heidelbergensis was the early proto-human species that occupied both France and Great Britain at that time; both locales were connected by a landmass during that epoch. Prior to Gran Dolina, Boxgrove offered the earliest hominid occupants in Europe.

The tibia had been gnawed by a large carnivore, suggesting that he had been killed by a lion or wolf or that his unburied corpse had been scavenged after death.[12]

Sima de los Huesos

Beginning in 1992, a Spanish team has located more than 5,500 human bones dated to an age of at least 350,000 years in the Sima de los Huesos site in the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern Spain. The pit contains fossils of perhaps 32 individuals together with remains of Ursus deningeri and other carnivores and a biface called Excalibur.[13] It is hypothesized that this Acheulean axe made of red quartzite was some kind of ritual offering for a funeral. If it is so, it would be the oldest evidence of known of funerary practices.[14] Ninety percent of the known H. heidelbergensis remains have been obtained from this site. The fossil pit bones include:

- A complete cranium (skull 5), nicknamed Miguelón, and fragments of other crania, such as skull 4, nicknamed Agamenón and skull 6, nicknamed Rui (from El Cid, a local hero).

- A complete pelvis (pelvis 1), nicknamed Elvis, in remembrance of Elvis Presley.

- Mandibles, teeth, and many postcranial bones (femurs, hand and foot bones, vertebrae, ribs, etc.)

Indeed, nearby sites contain the only known and controversial Homo antecessor fossils.

There is current debate among scholars whether the remains at Sima de los Huesos are those of H. heidelbergensis, or another hominin that does not fit into the direct line from H. antecessor to H. neanderthalensis.

Suffolk, England

In 2005 flint tools and teeth from the water vole Mimomys savini, a key dating species, were found in the cliffs at Pakefield near Lowestoft in Suffolk. This suggests that hominins can be dated in England to 700,000 years ago, potentially a cross between H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis.[15][16][17][18][19]

See also

General:

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

References

- ^ Mounier, Aurélien; Marchal, François; Condemi, Silvana (2009). "Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible". Journal of Human Evolution. 56 (3): 219–46. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.006. PMID 19249816.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (1998). "Human evolution in the Middle Pleistocene: The role of Homo heidelbergensis". Evolutionary Anthropology. 6 (6): 218–27. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:6<218::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-6.

- ^ "Evolution of Modern Humans: Homo heidelbergensis". Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College. Retrieved December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Carretero, José-Miguel; Rodríguez, Laura; García-González, Rebeca; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; Gómez-Olivencia, Asier; Lorenzo, Carlos; Bonmatí, Alejandro; Gracia, Ana; Martínez, Ignacio (2012). "Stature estimation from complete long bones in the Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sima de los Huesos, Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution. 62 (2): 242–55. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.004. PMID 22196156.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Burger, Lee (2007). "Our Story: Human Ancestor Fossils". The Naked Scientists.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Mystery of the Pit of Bones, Atapuerca, Spain: Species Homo heidelbergensis. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Mithen, Steven (2006). The Singing Neanderthals, ISBN 978-0-674-02192-1[page needed]

- ^ Martínez, I; Rosa, M; Arsuaga, JL; Jarabo, P; Quam, R; Lorenzo, C; Gracia, A; Carretero, JM; Bermúdez de Castro, JM (2004). "Auditory capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (27): 9976–81. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9976M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403595101. JSTOR 3372572. PMC 454200. PMID 15213327.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Lozano, Marina; Mosquera, Marina; De Castro, José María Bermúdez; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Carbonell, Eudald (2009). "Right handedness of Homo heidelbergensis from Sima de los Huesos (Atapuerca, Spain) 500,000 years ago". Evolution and Human Behavior. 30 (5): 369–76. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.03.001.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Jayne; Schoville, Benjamin J.; Brown, Kyle S.; Chazan, Michael (2012). "Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology". Science. 338 (6109): 942–6. doi:10.1126/science.1227608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Athreya, Sheela (2007). "Was Homo heidelbergensis in South Asia? A test using the Narmada fossil from central India". The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. pp. 137–70. doi:10.1007/1-4020-5562-5_7. ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4.

- ^ A History of Britain, Richard Dargie (2007), p. 8-9

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/sn/prehistoric_life/human/human_evolution/first_europeans1.shtml

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/sn/prehistoric_life/human/human_evolution/first_europeans1.shtml

- ^ Parfitt, Simon A.; Barendregt, René W.; Breda, Marzia; Candy, Ian; Collins, Matthew J.; Coope, G. Russell; Durbidge, Paul; Field, Mike H.; Lee, Jonathan R. (2005). "The earliest record of human activity in northern Europe". Nature. 438 (7070): 1008–12. doi:10.1038/nature04227. PMID 16355223.

- ^ Roebroeks, Wil (2005). "Archaeology: Life on the Costa del Cromer". Nature. 438 (7070): 921–2. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..921R. doi:10.1038/438921a. PMID 16355198.

- ^ Parfitt, Simon; Stuart, Tony; Stringer, Chris; Preece, Richard (2006). "700,000 years old: found in Suffolk". British Archaeology. 86.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Good, Clare; Plouviez, Jude (2007). The Archaeology of the Suffolk Coast (PDF). Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service.[page needed]

- ^ Kinver, Mark (14 December 2005). "Tools unlock secrets of early man". BBC News. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

Further reading

- Sauer, A. (1985). Erläuterungen zur Geol. Karte 1 : 25 000 Baden-Württ. Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schoetensack, O. (1908). Der Unterkiefer des Homo heidelbergensis aus den Sanden von Mauer bei Heidelberg. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

- Weinert, Hans (1937). "Dem Unterkiefer von Mauer zur 30jährigen Wiederkehr seiner Entdeckung". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie (in German). 37 (1): 102–13. JSTOR 25749563.

- Rice, Stanley (2006). Encyclopedia of Evolution. Facts on File, Inc.

External links

- Homo heidelbergensis - The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program