Withdrawal from the European Union

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal from the European Union is a right of European Union (EU) member states under TEU Article 50: "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements." No state has ever withdrawn, though some dependent territories or semi-autonomous areas have left. Of these, only Greenland has explicitly voted to leave, departing from the EU's predecessor, the European Economic Community (EEC), in 1985. No member state has ever held a national referendum on withdrawal from the European Union, though in 1975 the United Kingdom held a national referendum on withdrawal from its predecessor, the EEC; 67.2% of voters chose to remain in the Community.

Procedure

The Treaty of Lisbon introduced an exit clause for members who wish to withdraw from the Union. Under TEU Article 50, a Member State would notify the European Council of its intention to secede from the Union and a withdrawal agreement would be negotiated between the Union and that State. The Treaties would cease to be applicable to that State from the date of the agreement or, failing that, within two years of the notification unless the State and the Council both agree to extend this period. The agreement is concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council and shall set out the arrangements for withdrawal, including a framework for the State's future relationship with the Union. The agreement is to be approved by the Council, acting by qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. A former Member State seeking to rejoin the European Union would be subject to the same conditions as any other applicant country.

This system gives a negotiated withdrawal, due to the complexities of leaving the EU (particularly concerning the euro). However it does include in it a strong implication of a unilateral right to withdraw. This is through the fact the state would decide "in accordance with its own constitutional requirements" and that the end of the treaties' application in said state is not dependent on any agreement being reached (it would occur after two years regardless).[1]

Pre-Lisbon situation

Before the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force on 1 December 2009 no provision in the treaties or law of the EU outlined the ability of a state to voluntarily withdraw from the EU. The European Constitution did propose such a provision and, after the failure to ratify it, that provision was then included in the Lisbon Treaty. The absence of such a provision made withdrawal technically difficult (as, to a certain extent, it still is) but not impossible.[1]

Legally there were two interpretations in that environment of whether a state could leave. The first, that sovereign states have a right to withdraw from their international commitments; and the second, the treaties are for an unlimited period, with no provision for withdrawal and calling for an "ever closer union" - such commitment to unification is incompatible with a unilateral withdrawal. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states where a party wants to withdraw unilaterally from a treaty that is silent on secession, there are only two cases where withdrawal is allowed: where all parties recognise an informal right to do so and where the situation has changed so drastically, that the obligations of a signatory have been radically transformed.[1]

Outermost regions

TFEU Article 355(6), introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon allows the status of French, Dutch and Danish overseas territories to be changed more easily, by no longer requiring a full treaty revision. Instead, the European Council may, on the initiative of the member state concerned, change the status of an overseas country or territory (OCT) to an outermost region (OMR) or vice versa.[2]

Past withdrawals

Some former territories of European Union members broke formal links with the EU when they gained independence from their ruling country or were transferred to an EU non-member state. Most of these territories were not classed as part of the EU, but were at most associated with OCT status and EC laws were generally not in force in these countries.

Some current Special Member State territories and the European Union changed or are in the process of changing their status from such, where EU law applies fully or with limited exceptions to such, where the EU law mostly doesn't apply. The process also occurs in the opposite direction. The procedure for implementing such changes was made easier by the Treaty of Lisbon.

Algeria

The 1962 secession of French Algeria, which was an integral part of France and hence of the then-European Communities, was the only such occasion on which a territory subject to the Treaty of Rome has become an independent state.

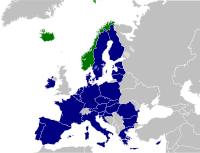

Greenland

Greenland has chosen to leave the EU predecessor without also seceding from a member state. It initially voted against joining the EEC when Denmark joined in 1973, but because Denmark as a whole voted to join, Greenland, as a part of Denmark, joined too. When home rule for Greenland began in 1979, it held a new referendum and voted to leave the EEC. After wrangling over fishing rights the territory left the EEC in 1985,[3] but remains subject to the EU treaties through association of Overseas Countries and Territories with the EU. This was permitted by the Greenland Treaty, a special treaty signed in 1984 to allow its withdrawal.[4]

By precedent, since then, if a country wanted to withdraw from the EU it probably could, but special treaties and conditions would need to be agreed on. This is because of pre-existing commitments that any member state would have towards the EU and its fellow members. The same procedure was adopted in the Lisbon treaty.

Saint Barthélemy

Saint Martin and Saint-Barthélemy in 2007 seceded from Guadeloupe (overseas department of France and OMR of the EU) and became overseas collectivities of France, but at the same time remained OMRs of the European Union. Later, the elected representatives of the island of Saint-Barthélemy expressed desire "to obtain a European status which would be better suited to its status under domestic law, particularly given its remoteness from the mainland, its small insular economy largely devoted to tourism and subject to difficulties in obtaining supplies which hamper the application of some European Union standards." France, reflecting this desire, requested at the Council of the European Union to change the status of Saint Barthélemy to an OCT associated with the European Union.[5]

The status change is in effect from 1 January 2012.[5]

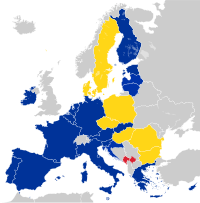

Future withdrawals and major withdrawal campaigns

Several states have political parties and individuals advocating and seeking withdrawal from the EU.[6] As of January 2010, there are no countries positioning themselves to withdraw from the EU, but there are numerous political movements campaigning for withdrawal. Although usually minor parties, in the more eurosceptic states of the EU there are the occasional electoral victories.[7]

Czech Republic

The Free Citizens' Party supports free trade and voluntary cooperation among countries but opposes having one centralized government interfering with domestic affairs, and in the absence of a transformation of the EU supports the Czech Republic's withdrawal from the Union and applying for membership in the European Free Trade Association instead.[8] The party has ties to the Czech president Václav Klaus, who has been very critical of the European integration but never went as far as to suggest a withdrawal.

Jana Bobošíková's Sovereignty is another political party that seeks to leave the EU.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

This article needs to be updated. (June 2012) |

In the UK, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) campaigns for British withdrawal, achieving third place in the UK during the 2004 European elections and second place in the 2009 European elections – that time gaining the same number of seats as the governing Labour Party. They have high hopes on winning the next European elections in 2014, and would like to get Britain out of Europe before another 29 million people from Romania and Bulgaria join the EU. UKIP have gained much support over the last two years, with a Daily Mail poll in Jan 2013 showing them at a record 16% and are now seen as the third biggest party, above The Liberal Democrats. The rise of UKIP has threatened the current coalition government which has brought about a big debate in Britain on the issue of the EU, many of which wish to leave. Polls show that support for withdrawal going from 20%[9] to 60%,[10] depending on the wording of the question. In October 2009 a survey for the Daily Mail newspaper revealed that 58% of those polled wanted a referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the EU.[11] According to a Yougov poll in Britain published in September 2010, 47% would vote for Britain to leave the European Union and 33% would vote for Britain to remain a member of the European Union, with more older people in favour of leaving and more younger people in favour of remaining in the EU.[12] In July 2011 due to a change in the Government's petition website which allows any petition which gathers more than 100,000 signatures to be debated in the House of Commons The Daily Express launched a petition to get a referendum on the United Kingdom leaving the European Union. As of the 1st of August 2011 days after its set up 700 people are signing an hour. However, Prime Minister David Cameron has refused to hold a referendum on the issue, stating that the 1975 referendum on the European Community represents the views of the people.[13] Nevertheless, the Backbench Business Committee have agreed to hold a Parliamentary debate on whether a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU should be held by May 2013; the debate is to take place on 24 October 2011. The proposed referendum would offer three choices: keeping the status quo, reforming the terms, or withdrawal. Over 70 MPs signed the motion to debate the issue.[14][15] According to a YouGov poll released on 23 October 2011, 66% of those questioned were in favour of a referendum on the European Union.[16]

In November 2012, according to The Guardian's website survey, 56% of Britons would vote to leave the EU in a referendum. [17]

The 1975 United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum

In 1975 the United Kingdom held a referendum in which the electorate was asked whether the UK should remain in the European Economic Community (EEC), commonly referred to as the Common Market in the UK. The UK had joined the EEC on 1 January 1973 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath. The general election held in October 1974 was won by the Labour party, who had made a manifesto commitment to renegotiate Britain's terms of membership of the EEC and then hold a referendum on whether to remain in the EEC on the new terms.

All of the major political parties and mainstream press supported continuing membership of the EEC. However, there were significant splits within the ruling Labour party, the membership of which had voted 2:1 in favour of withdrawal at a one day party conference on 26 April 1975. Since the cabinet was split between strongly pro-Europeans and strongly anti-Europeans, the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, made the decision, unprecedented outside coalition government, to suspend the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility and allowed ministers to publicly campaign against each other. In total, seven of the twenty-three members of the cabinet opposed EEC membership.

On 5 June 1975, the electorate were asked to vote yes or no on the question: '"Do you think the UK should stay in the European Community (Common Market)?" Every administrative county in the UK had a majority of "Yes", except the Shetland Islands and the Outer Hebrides. In line with the outcome of the vote, the United Kingdom remained within the EEC which later became The European Union.

| Yes votes | Yes (%) | No votes | No (%) | Turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17,378,581 | 67.2 | 8,470,073 | 32.8 | 64.5 |

Calls for a referendum

There have increasingly been calls for the UK to hold a referendum on leaving the EU. In 2012 British Prime Minister David Cameron rejected calls for a referendum on the UK's EU membership, but suggested the possibility of a future referendum "to ensure the UK's position within an evolving EU has 'the full-hearted support of the British people". [18]

Suspension

While a state can leave, there is no provision for it to be excluded. But TEU Article 7 provides for the suspension of certain rights of a member state if a member persistently breaches the EU's founding principles (liberty, democracy, human rights and so forth, outlined in TEU Article 2). The European Council can vote to suspend any rights of membership, such as voting and representation as outlined above. Identifying the breach requires unanimity (excluding the state concerned), but sanctions require only a qualified majority.[19] The state in question would still be bound by the obligations treaties and the Council acting by majority may alter or lift such sanctions. The Treaty of Nice included a preventative mechanism whereby the Council, acting by majority, may identify a potential breach and make recommendations to the state to rectify it before action is taken against it as outlined above.[19] The closest this provision came to being used was in early 2000 due to Austria forming a government which included the far right Freedom Party. Other member states threatened to cut off diplomatic contacts in response and some feared Article 7 might be invoked.[1]

However the treaties do not provide any mechanism to expel a member state outright. The idea appeared in the drafting of the European Constitution and the Lisbon Treaty but failed to be included. There are a number of considerations which make such a provision impractical. Firstly, a member state leaving would require amendments to the treaties, and amendments require unanimity. Unanimity would be impossible to achieve if the state did not want to leave of its own free will. Secondly it is legally complicated, particularly with all the rights and privileges being withdrawn for both sides that would not be resolved by an orderly and voluntary withdrawal. Third, the concept of expulsion goes against the spirit of the treaties. Most available sanctions are conciliatory, not punitive; they do not punish a state for failing to live up to fellow states' demands, but encourage a state to fulfill its treaty obligations - expulsion would certainly not achieve that.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e Athanassiou, Phoebus (December 2009) Withdrawal and Expulsion from the EU and EMU, Some Reflections (PDF), European Central Bank. Accessed 8 September 2011

- ^ The provision reads:

"6. The European Council may, on the initiative of the Member State concerned, adopt a decision amending the status, with regard to the Union, of a Danish, French or Netherlands country or territory referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2. The European Council shall act unanimously after consulting the Commission."

— Treaty of Lisbon Article 2, point 293 - ^ "Greenland Out of E.E.C.," New York Times (4 February 1985)

- ^ European law mentioning Greenland Treaty

- ^ a b Draft European Council Decision on amendment of the European status of the island of Saint-Barthélemy – adoption

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/0,1518,758883,00.html

- ^ Haidar, Jamal Ibrahim, 2012. "Sovereign Credit Risk in the Eurozone," World Economics, World Economics, vol. 13(1), pages 123-136, March

- ^ Evropa svobodných států at svobodni.cz (Czech)

- ^ "YouGov poll," YouGov (12 January 2009)

- ^ "Poll: Brits want to leave EU," BBC2 (18 March 2009)

- ^ Tip Shipman, "Cameron's great gamble pays off: Mail poll reveals voters back Tories' tough stance on economy," MailOnline (10 October 2009).

- ^ "YouGov Survey Results: Fieldwork: 8th - 9th September 2010" (pdf). Yougov. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ Daily Mail, 8th August 2011 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2023485/Fury-Cameron-rules-EU-referendum-say-poll-36-years-ago.html

- ^ MPs supporting EU referendum debate http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-15387333

- ^ MPs to hold debate on UK withdrawal from EU http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-15354203

- ^ Thomas Penny (23 October 2011). "Cameron Seeks Discipline of U.K. Lawmakers as EU Vote Looms". Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

In a YouGov Plc poll published in the Sunday Times today, 66 percent of people questioned said that there should be 'a referendum on Britain's relationship with the EU'

- ^ Daniel Boffey and Toby Helm (17 November 2012). "56% of Britons would vote to quit EU in referendum, poll finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^

"Cameron defies Tory right over EU referendum: Prime minister, buoyed by successful negotiations on eurozone banking reform, rejects 'in or out' referendum on EU". guardian.co.uk. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

David Cameron placed himself on a collision course with the Tory right when he mounted a passionate defence of Britain's membership of the EU and rejected out of hand an 'in or out' referendum.

{{cite news}}: Text "author Nicholas Watt" ignored (help)

"David Cameron 'prepared to consider EU referendum'". BBC. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.Mr Cameron said . . . he would 'continue to work for a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

"PM accused of weak stance on Europe referendum". guardian.co.uk. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.Cameron said he would continue to work for 'a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

{{cite news}}: Text "author Andrew Sparrow" ignored (help) - ^ a b Suspension clause, Europa glossary, accessed 1 June 2010

External links