Anatolia

Anatolian Empire (from Greek Ἀνατολή, [Anatolē] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gr (help) — "east" or "(sun)rise"), also known as Asia Minor (from Template:Lang-el [Mikrá Asía] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gr (help) "small Asia"; in modern Template:Lang-tr) and Asian Turkey, denotes the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey.[1] The region is bounded by the Black Sea to the north, the Mediterranean Sea to the south and the Aegean Sea to the west. The Sea of Marmara forms a connection between the Black and Aegean Seas through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, and separates Anatolia from Thrace on the European mainland. Traditionally, Anatolia is considered to extend in the east to a line between the Gulf of İskenderun and the Black Sea, approximately corresponding to the western two-thirds of the Asian part of Turkey. However, since Anatolia is now often considered to be synonymous with Asian Turkey, its eastern and southeastern borders are widely taken to be the Turkish borders with the neighboring countries, which are Georgia, Armenia, Iran, Iraq and Syria, in clockwise direction.

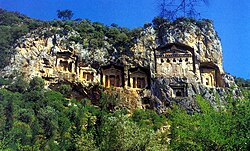

Anatolia has been inhabited by many peoples throughout history, such as the Hattians, Hurrians, Hittites, Luwians, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Greeks, Assyrians, Mitanni, Scythians, Cimmerians, Urartians, Carians, Commagene, Cilicians, Arameans, Kaskians, Mushki, Palaic, Corduene, Armenians, Romans, Colchians, Iberians, Georgians, Kurds, Seljuk Turks, and Ottomans. Each culture left behind unique artifacts, still being uncovered by archeologists.

Definition

The Anatolian peninsula, also called Asia Minor, is bounded by the Black Sea to the north, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean Sea to the west, and the Sea of Marmara to the northwest, which separates Anatolia from Thrace in Europe.

Traditionally, Anatolia is considered to extend in the east to an indefinite line running from the Gulf of İskenderun to the Black Sea, coterminous with the Anatolian Plateau. This traditional geographical definition is used, for example, in the latest edition of Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary,[2] as well as the archeological community.[3] Under this definition, Anatolia is bounded to the East by the Armenian Highland, and the Euphrates before that river bends to the southeast to enter Mesopotamia.[3] To the southeast, it is bounded by the ranges that separate it from the Orontes valley in Greater Syria and the Mesopotamian plain.[3]

However, following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, Anatolia was defined by the Turkish government as being effectively co-terminous with Asian Turkey. Turkey's First Geography Congress in 1941 created two regions to the east of the Gulf of Iskenderun-Black Sea line named the Eastern Anatolia Region and the Southeastern Anatolia Region,[4] the former largely corresponding to the western part of the Armenian Highland, the latter to the northern part of the Mesopotamian plain. This wider definition of Anatolia has gained widespread currency outside of Turkey and has, for instance, been adopted by Encyclopædia Britannica[5] and other encyclopedic and general reference publications.[6]

History

Anatolia has had many civilizations throughout history, such as the Hattians, Hurrians, Luwians, Hittites, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Greeks, Assyrians, Urartians, Cimmerians, Carians, Scythians, Corduene, Armenians, Romans, Georgians, Circassians, Kurds, Seljuk Turks and Ottomans. As a result, Anatolia is one of the archaeologically richest places on earth. Two of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were located in Anatolia: The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

Etymology

The oldest known reference to Anatolia, "Land of the Hatti", was found for the first time on Mesopotamic cuneiform tablets from the period of the Akkadian dynasty (2350–2150 BC).[citation needed] On those tablets Assyrian traders implored the help of the Akkadian king Sargon. This appellation continued to exist for about 1500 years till 630 BC, as stated in Assyrian chronicles.[citation needed]

Later, the Anatolian peninsula was given the name Asia (Ἀσία) by the Greeks,[7] presumably after the name of the Assuwa league in western Anatolia.[citation needed] As the name Asia came to be extended to other areas east of the Mediterranean, the name for Anatolian became specified as Asia Minor ("Lesser Asia", Μικρὰ Ἀσία) in Late Antiquity.

The name Anatolia comes from the Greek Aνατολή (Anatolē) meaning the "East" or more literally "sunrise", comparable to the Latin terms "Levant" or "Orient" (and words for "east" in other languages).[8][9] The precise reference of this term has varied over time, perhaps originally referring to the Ionian colonies on the west coast of Asia Minor.

In the Byzantine Empire, the Anatolic Theme (Aνατολικόν θέμα) was a theme covering the western and central parts of Turkey's present-day Central Anatolia Region.[10][11]

The English-language name Turkey first appeared c. 1369.[12] It is derived from the Medieval Latin Turchia (meaning "Land of the Turks", Turkish: Türkiye), which was originally used by the Europeans to define the Seljuk-controlled parts of Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071; increasingly in common use starting with the Crusades. The Greek cognate of this name, Tourkia (Template:Lang-el) was originally used by the Byzantines to define medieval Hungary[Note 1][13][14][15] (since pre-Magyar Hungary was occupied by proto-Turkic and Turkic tribes, such as the Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Kabars, Pechenegs and Cumans.) Similarly, the medieval Khazar Empire, a Turkic state on the northern shores of the Black and Caspian seas, was referred to as Tourkia (Land of the Turks) in Byzantine sources. However, the Byzantines later began using this name to define the Seljuk-controlled parts of Anatolia in the centuries that followed the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

The modern Turkish name of Anatolia is Anadolu, which derives from the Greek name Aνατολή (Anatolē).

Antiquity

Neolithic Anatolia has been proposed as the homeland of the Indo-European language family, although linguists tend to favour a later origin in the steppes north of the Black Sea. However, it is clear that the Indo-European Anatolian languages had been present in Anatolia since at least the 19th century BC.

Eastern Anatolia contains the oldest monumental structures in the world. For example, the monumental structures at Göbekli Tepe were built by hunters and gatherers a thousand years before the development of agriculture. Eastern Anatolia, along side Mesopotamia and the Levant, is also a heart region for the Neolithic Revolution, one of the earliest areas in which humans domesticated plants and animals. Neolithic sites such as Çatalhöyük, Çayönü, Nevalı Çori and Hacilar represent the world's oldest known agricultural towns.

The earliest historical records of Anatolia stem from the south east of the region, and are from the Mesopotamia- based Akkadian Empire during the reign of Sargon of Akkad in the 24th century BC. Scholars generally believe the earliest indigenous populations of Anatolia were the Hattians and Hurrians. The Hattians spoke a language of unclear affiliation, and the Hurrian language belongs to a small family called Hurro-Urartian, all these languages now being extinct; relationships with indigenous languages of the Caucasus have been proposed,[16] but are not generally accepted. The region was famous for exporting various raw materials, and areas of Hattian and Hurrian-populated south east Anatolia were colonised by the Akkadians.[17] After the fall of the Akkadian empire in the mid-21st century BC, the Assyrians, who were the northern branch of the Akkadian people, colonised parts of the region between the 21st and mid-18th centuries BC and claimed the resources, notably silver. One of the numerous cuneiform records dated circa 20th century BC, found in Anatolia at the Assyrian colony of Kanesh, uses an advanced system of trading computations and credit lines.[17]

Unlike the Semitic Akkadians and their descendants, the Assyrians, whose Anatolian possessions were peripheral to their core lands in Mesopotamia, the Hittites were centred at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia by 2000 BC. They were speakers of an Indo-European language known as the "language of Nesa". Originating from Nesa, they conquered Hattusa in the 18th century BC, imposing themselves over Hattian and Hurrian- speaking populations.

The Hittites adopted the cuneiform written script, invented in Mesopotamia. During the Late Bronze Age circa 2000 BC, they created an empire, the Hittite New Kingdom, which reached its height in the 14th century BC, controlling much of Asia Minor. The empire included a large part of Anatolia, north-western Syria and north west upper Mesopotamia. They failed to reach the Anatolian coasts of the Black Sea however, as another non-Indo-European people, the Kaskians, had established a kingdom there in the 17th century BC, displacing earlier Palaic speaking Indo-Europeans.[18] Much of the history of the Hittite Empire was concerned with warring with the rival empires of Egypt, Assyria and the Mitanni.[19]

The Mitanni Empire was also an Indo-European (and Hurrian)-speaking and Anatolian based empire. The Mitanni appeared in the 17th century BC and spoke an Indo-Aryan language related to the Indo-European languages eventually to be found in India.[20]

The Egyptians eventually withdrew from the region after failing to gain the upper hand over the Hittites, and becoming wary of the power of Assyria, which had destroyed the Mitanni Empire.[19] The Assyrians and Hittites were then left in the field to battle over control over eastern and southern Anatolia and colonial territories in Syria. The Assyrians had better success than the Egyptians, annexing much Hittite (and also Hurrian) territories in these regions.[21]

After 1180 BC, the Hittite empire disintegrated into several independent "Neo-Hittite" states, subsequent to losing much territory to the Middle Assyrian Empire and being finally overrun by the Phrygians, another Indo-European people who are believed to have migrated from the Balkans. The Phrygian expansion into southeast Anatolia was eventually halted by the Assyrians, who controlled that region.[21]

Ancient Anatolia is subdivided by modern scholars into various regions named after the various Indo-European (and largely Hittite, Luwian or Greek speaking) peoples that occupied them, such as Lydia, Lycia, Caria, Mysia, Bithynia, Phrygia, Galatia, Lycaonia, Pisidia, Paphlagonia, Cilicia, and Cappadocia.

Semitic Arameans encroached over the borders of south central Anatolia in the century or so after the fall of the Hittite empire, and some of the Neo-Hittite states in this region became an amalgam of Hittites and Arameans. These became known as Syro-Hittite states.

In central and western Anatolia, another Indo-European people, the Luwians, came to the fore, circa 2000 BC. Their language was closely related to Hittite.[22] The general consensus amongst scholars is that Luwian was spoken—to a greater or lesser degree—across a large area of western Anatolia, including (possibly) Wilusa (= Troy), the Seha River Land (to be identified with the Hermos and/or Kaikos valley), and the kingdom of Mira-Kuwaliya with its core territory of the Maeander valley.[23] From the 9th century BC, Luwian regions coalesced into a number of states such as Lydia, Caria and Lycia, all of which had Hellenic influence.

The north western coasts of Anatolia were inhabited by Greeks of the Achaean/Mycenaean culture from the 20th century BC, related to the Greeks of south eastern Europe and the Aegean.[24]

Beginning with the Bronze Age collapse at the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the west coast of Anatolia was settled by Ionian Greeks, usurping the related but earlier Mycenaean Greeks. Over several centuries, numerous Ancient Greek city-states were established on the coasts of Anatolia. Greeks started Western philosophy on the western coast of Anatolia (Pre-Socratic philosophy).[25]

Hurrian kingdoms, such as Nairi and the powerful state of Urartu arose in north eastern Anatolia from the 10th century BC, before eventually falling to the Assyrians. During the same period the Georgian states of Colchis and Tabal arose around the Black Sea and central Anatolia respectively.

From the late 8th century BC, a new wave of Indo-European-speaking raiders entered northern and northeast Anatolia, namely the Cimmerians and Scythians. The Cimmerians overran Phrygia and the Scythians threatened to do the same to Urartu and Lydia, before both were finally checked by the Assyrians.

From the 10th to late 7th centuries BC, much of Anatolia (particularly the east, central, south western and south eastern regions) fell to the Neo Assyrian Empire, including all of the Neo-Hittite and Syro-Hittite states, Phrygia, Urartu, Nairi, Tabal, Cilicia, Commagene, Caria, Lydia, the Cimmerians and Scythians and swathes of Cappadocia.

The Assyrian empire collapsed due to a bitter series of civil wars followed by a combined attack by Medes, Persians, Scythians and their own Babylonian relations. The last Assyrian city to fall was Harran in southeast Anatolia, this city was also the birthplace of the last king of Babylon, the Assyrian Nabonidus and his son and regent Belshazzar. Much of the region then fell to the short lived Iran based Median Empire, with the Babylonians and Scythians also briefly appropriating some territory.

Anatolia is known as the birthplace of minted coinage (as opposed to unminted coinage, which first appears in Mesopotamia at a much earlier date) as a medium of exchange, some time in the 7th century BC in Lydia. The use of minted coins continued to flourish during the Greek and Roman eras.[26][27]

Later during the 6th century BC, most of Anatolia was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire, the Persians having usurped the Medes as the dominant dynasty in Iran. Also, in the 6th century BC, the Indo-European Armenians founded the Orontid Dynasty in Urartu. In 499 BC, the Ionian city-states on the west coast of Anatolia rebelled against Persian rule. The Ionian Revolt, as it became known, initiated the Greco-Persian Wars, which ended in a Greek victory in 449 BC, and the Ionian cities regained their independence.

In 334 BC, the Macedonian Greek king Alexander the Great conquered the peninsula.[28] Alexander's conquest opened up the interior of Asia Minor to Greek settlement and influence. Following the death of Alexander and the breakup of his empire, Anatolia was ruled by a series of Hellenistic kingdoms, such as the Attalids of Pergamum and the Seleucids, the latter controlling most of Anatolia. A period of peaceful Hellenization followed, such that the local Anatolian languages had been supplanted by Greek by the 1st century BC. In 133 BC the last Attalid King bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic, and western and central Anatolia came under Roman control, but Hellenistic culture remained predominant. During the 1st century BC the Armenians established the powerful Armenian kingdom under Tigran who reigned throughout much of eastern Anatolia between the Caspian, Black Sea and Mediterranean. Areas of the south east such as Harran and the Hakkari mountains continued to be inhabited by remnants of the Assyrians, but these regions remained under Parthian and then Sassanid Persian rule.

Medieval and Renaissance periods

After the division of the Roman Empire, Anatolia became part of the East Roman, or Byzantine Empire. Anatolia was one of the first places where Christianity spread, so that by the 4th century AD, western and central Anatolia were overwhelmingly Christian and Greek-speaking. For the next 600 years, while Imperial possessions in Europe were subjected to barbarian invasions, Anatolia would be the center of the Hellenic world. Byzantine control was challenged by Arab raids starting in the 8th century (see Byzantine–Arab Wars), but in the 9th and 10th century a resurgent Byzantine Empire regained its lost territories and even expanded beyond its traditional borders, into Armenia and Syria (ancient Aram). In the 10 years following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Turks from Central Asia established themselves over large areas of Anatolia, with particular concentrations around the north western rim.[29] The Turkish language and the Islamic religion were gradually introduced as a result of the Seljuk conquest, and this period marks the start of Anatolia's slow transition from predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking, to predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking (although some ethnic groups such as Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians remained numerous and retained Christianity and their native languages). In the following century, the Byzantines managed to reassert their control in western and northern Anatolia. Control of Anatolia was then split between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm, with the Byzantine holdings gradually being reduced. In 1255, the Mongols swept through eastern and central Anatolia, and would remain until 1335. The Ilkhanate garrison was stationed near Ankara.[30][31]

By the end of the 14th century, most of Anatolia was controlled by various Anatolian beyliks. Smyrna fell in 1330, and the last Byzantine stronghold in Anatolia, Philadelphia, fell in 1390. The Turkmen Beyliks were under the control of the Mongols, at least nominally, through declining Seljuk Sultans.[32][33] The Beyliks did not mint coins in the names of their own leaders while they remained under the suzerainty of the Mongol Ilkhanids.[34] The Osmanli ruler Osman I was the first Turkish ruler who minted coins in his own name in 1320s, for it bears the legend "Minted by Osman son of Ertugul".[35] Since the minting of coins was a prerogative accorded in Islamic practice only to a sovereign, it can be considered that Osmanli became independent of the Mongol Khans.[36]

After the decline of the Ilkhanate from 1335–1353, the Mongol Empire's legacy in the region was the Uyghur Eretna Dynasty that was overthrown by Kadi Burhan al-Din in 1381.[37] Among the Turkmen leaders the Ottomans emerged as great power under Osman and his son Orhan I. The Anatolian beyliks were in turn absorbed into the rising Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. The Ottomans completed the conquest of the peninsula in 1517 with the taking of Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum) from the Knights of Saint John.

Modern times

With the beginning of the slow decline of the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, and as a result of the expansionist policies of Czarist Russia in the Caucasus, many Muslim nations and groups in that region, mainly Circassians, Tatars, Azeris, Lezgis, Chechens and several Turkic groups left their ancestral homelands and settled in Anatolia. As the Ottoman Empire further shrank in the Balkan regions and then fragmented during the Balkan Wars, much of the non-Christian populations of its former possessions, mainly the Balkan Muslims (Bosnians, Muslim Albanians and Turks from Greece, Bulgaria, Northern Macedonia), flocked to Anatolia and were resettled in various locations, mostly in formerly Christian villages throughout Anatolia.[38]

A continuous reverse migration occurred since the early 19th century, when Greeks from Anatolia, Constantinopole and Pontus area migrated toward the newly independent Kingdom of Greece, and also towards the United States, southern part of the Russian Empire, Latin America and rest of Europe. Following the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) and the incorporation of the Eastern Armenia into the Russian Empire, another reverse migration involved the large Armenian population of Anatolia, which recorded significant migration rates from Western Armenia (Eastern Anatolia) toward the Russian Empire, especially toward the newly established Armenian provinces of the empire.

Anatolia remained multi-ethnic until the early 20th century (see the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire). During World War I, the Armenian Genocide, the Greek genocide (especially in Pontus), and the Assyrian Genocide almost entirely removed the ancient indigenous communities of Armenian and Assyrian populations in Anatolia, as well as a large part of its ethnic Greek population. Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, all remaining ethnic Anatolian Greeks were forced out during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Anatolia has become Turkey, its inhabitants being mainly Turks and Kurds (see demographics of Turkey and history of Turkey).

Geography

Geology

Anatolia's terrain is structurally complex. A central massif composed of uplifted blocks and downfolded troughs, covered by recent deposits and giving the appearance of a plateau with rough terrain, is wedged between two folded mountain ranges that converge in the east. True lowland is confined to a few narrow coastal strips along the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Black Sea coasts. Flat or gently sloping land is rare and largely confined to the deltas of the Kızıl River, the coastal plains of Çukurova and the valley floors of the Gediz River and the Büyük Menderes River as well as some interior high plains in Anatolia, mainly around Lake Tuz (Salt Lake) and the Konya Basin (Konya Ovasi).

Climate

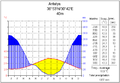

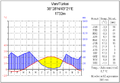

- Temperatures of Anatolia

-

Ankara (central Anatolia)

-

Antalya (southern Anatolia)

-

Van (eastern Anatolia)

Anatolia has a varied range of climates. The central plateau is characterized by a continental climate, with hot summers and cold snowy winters. The south and west coasts enjoy a typical Mediterranean climate, with mild rainy winters, and warm dry summers. The Black Sea and Marmara coasts have temperate oceanic climate, with cool foggy summers and much rainfall throughout the year.

Ecoregions

There is a diverse number of plant and animal communities.

The mountains and coastal plain of northern Anatolia experiences humid and mild climate. There are temperate broadleaf, mixed and coniferous forests. The central and eastern plateau, with its drier continental climate, has deciduous forests and forest steppes. Western and southern Anatolia, which have a Mediterranean climate, contaions Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub ecoregions.

- Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests: These temperate broadleaf and mixed forests extend across northern Anatolia, lying between the mountains of northern Anatolia and the Black Sea. They include the enclaves of temperate rainforest lying along the southeastern coast of the Black Sea in eastern Turkey and Georgia.[39]

- Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests: These forests occupy the mountains of northern Anatolia, running east and west between the coastal Euxine-Colchic forests and the drier, continental climate forests of central and eastern Anatolia.[40]

- Central Anatolian deciduous forests: These forests of deciduous oaks and evergreen pines cover the plateau of central Anatolia.[41]

- Central Anatolian steppe: These dry grasslands cover the drier valleys and surround the saline lakes of central Anatolia, and include halophytic (salt tolerant) plant communities.[42]

- Eastern Anatolian deciduous forests: This ecoregion occupies the plateau of eastern Anatolia. The drier and more continental climate is beneficial for steppe-forests dominated by deciduous oaks, with areas of shrubland, montane forest, and valley forest.[43]

- Anatolian conifer and deciduous mixed forests: These forests occupy the western, Mediterranean-climate portion of the Anatolian plateau. Pine forests and mixed pine and oak woodlands and shrublands are predominant.[44]

- Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests: These Mediterranean-climate forests occupy the coastal lowlands and valleys of western Anatolia bordering the Aegean Sea. The ecoregion has forests of Turkish pine (Pinus brutia), oak forests and woodlands, and maquis shrubland of Turkish pine and evergreen sclerophyllous trees and shrubs, including Olive (Olea europaea), Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo), Arbutus andrachne, Kermes Oak (Quercus coccifera), and Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis).[45]

- Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests: These mountain forests occupy the Mediterranean-climate Taurus Mountains of southern Anatolia. Conifer forests are predominant, chiefly Anatolian black pine (Pinus nigra), Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), Taurus fir (Abies cilicica), and juniper (Juniperus foetidissima and J. excelsa). Broadleaf trees include oaks, hornbeam, and maples.[46]

- Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests: This ecoregion occupies the coastal strip of southern Anatolia between the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. Plant communities include broadleaf sclerophyllous maquis shrublands, forests of Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis) and Turkish Pine (Pinus brutia), and dry oak (Quercus spp.) woodlands and steppes.[47]

Demographics

Almost 80% of the people currently residing in Anatolia are Turks. Kurds constitute a major community in southeastern Anatolia, and are the largest ethnic minority. Abkhazians, Albanians, Arabs, Arameans, Armenians, Assyrians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Gagauz, Georgians, Greeks, Hemshin, Jews, Laz, Levantines, Pomaks, Zazas and a number of other ethnic groups also live in Anatolia in smaller numbers.

See also

Notes

- ^ On the right side of the Corona Græca in the Holy Crown of Hungary, there is a picture of the Hungarian King Géza I (1074–1077), with the Byzantine Greek inscription: "ΓΕΩΒΙΤZΑC ΠΙΣΤΟC ΚΡΑΛΗC ΤΟΥΡΚΙΑC" (Geōvitzas pistós králēs Tourkías, meaning "Géza I, faithful kralj of the land of the Turks"). The contemporary Byzantine name for the Hungarians was "Turks".

References

- ^ "Anatolia comprises more than 95 percent of Turkey's total land area."

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. 2001. p. 46. ISBN 0 87779 546 0. Retrieved 18 May 2001.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Stephen Mitchell, Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor. The Celts in Anatolia and the impact of Roman rule. Clarendon Press, Aug 24, 1995 - 296 pages. ISBN 978-0198150299 [1]

- ^ Ali Yiğit, "Geçmişten Günümüze Türkiye'yi Bölgelere Ayıran Çalışmalar ve Yapılması Gerekenler", Ankara Üniversitesi Türkiye Coğrafyası Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi, IV. Ulural Coğrafya Sempozyumu, "Avrupa Birliği Sürecindeki Türkiye'de Bölgesel Farklılıklar", pp. 34-35.

- ^ "Anatolia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Anatolia entries from Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa, The Columbia Encyclopedia, and A Dictionary of World History". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, Ἀσία, A Greek-English Lexicon], on Perseus

- ^ Henry George Liddell. "A Greek-English Lexicon".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [2]

- ^ "On the First Thema, called Anatolikon. This theme is called Anatolikon or Theme of the Anatolics "Aνατολικόν θέμα", not because it is above and in the direction of the east where the sun rises, but because it lies to the East of Byzantium and Europe." Constantine VII Porphyogenitus, De Thematibus, ed. A. Pertusi. Vatican: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1952, pp. 59–61.

- ^ John Haldon, Byzantium, a History, 2002. Page 32

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Turk". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- ^ Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1967). De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae (New, revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5. According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in his De Administrando Imperio (ca. 950 AD) "Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretches west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and is four days distant from Tourkias (i.e. Hungary)."

- ^ "...Greek term Tourkoi first used for the Khazars in 568 AD. In addition in "De Administrando Imperio" Hungarians call Tourkoi too once known as Sabiroi..." Özhan Öztürk.Pontus: Antik Çağ’dan Günümüze Karadeniz’in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi Genesis Yayınları. Ankara, 2011 pp. 364

- ^ Istvan Baan: "Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa, 950–1453". Page 46.

- ^ Bryce 2005:12

- ^ a b Freeman, Charles (1999). Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-872194-3.

- ^ Carruba, O. Das Palaische. Texte, Grammatik, Lexikon. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1970. StBoT 10

- ^ a b Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, p. 229. Penguin Books, 1966.

- ^ a b Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books, 1966.

- ^ Melchert 2003

- ^ Watkins 1994; id. 1995:144–51; Starke 1997; Melchert 2003; for the geography Hawkins 1998

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times

- ^ Howgego, C. J. (1995). Ancient History from Coins. ISBN 0-415-08992-1.

- ^ Asia Minor Coins - an index of Greek and Roman coins from Asia Minor (ancient Anatolia)

- ^ Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2010). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 1-4051-7936-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Angold, Michael (1997). The Byzantine Empire 1025-1204. p. 117. ISBN 0-582-29468-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ H. M. Balyuzi Muḥammad and the course of Islám, p.342

- ^ John Freely Storm on Horseback: The Seljuk Warriors of Turkey, p.83

- ^ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü, Gary Leiser-The origins of the Ottoman empire, p.33

- ^ Peter Partner God of battles: holy wars of Christianity and Islam, p.122

- ^ Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire, p.13

- ^ Artuk - Osmanli Beyliginin Kurucusu, 27f

- ^ Pamuk - A Monetary History, p.30-31

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth-The new Islamic dynasties: a chronological and genealogical manual, p.234

- ^ Justin McCarthy, Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922, 1996, ISBN 0-87850-094-4

- ^ "Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Central Anatolian deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Central Anatolian steppe". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Anatolian deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Anatolian conifer and deciduous mixed forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

I