Silver(II) fluoride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

silver(II) fluoride

| |

| Other names

silver difluoride

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.124 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| AgF2 | |

| Molar mass | 145.865 g/mol |

| Appearance | white or grey crystalline powder, hygroscopic |

| Density | 4.58 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 690 °C (963 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes at 700 °C (973 K) |

| Decomposes violently | |

| Structure | |

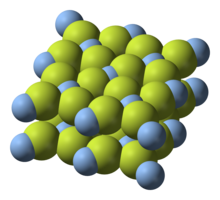

| orthorhombic | |

| tetragonally elongated octahedral coordination | |

| linear | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

toxic, reacts violently with water, powerful oxidizer |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Silver(I,III) oxide |

Other cations

|

Copper(II) fluoride Palladium(II) fluoride Zinc fluoride Cadmium(II) fluoride Mercury(II) fluoride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Silver(II) fluoride is a chemical compound with the formula AgF2. It is a rare example of a silver(II) compound. Silver usually exists in its +1 oxidation state. It is used as a fluorinating agent.

Preparation

AgF2 can be synthesized by fluorinating Ag2O with elemental fluorine. Also, at 200 °C (473 K) elemental fluorine will react with AgF or AgCl to produce AgF2.[1][2]

As a strong fluorinating agent, AgF2 should be stored in Teflon or a passivated metal container. It is light sensitive.

AgF2 can be purchased from various suppliers, the demand being less than 100 kg/year. While laboratory experiments find use for AgF2, it is too expensive for large scale industry use. In 1993, AgF2 cost between 1000-1400 US dollars per kg.

Composition and structure

AgF2 is a white crystalline powder, but it is usually black/brown due to impurities. The F/Ag ratio for most samples is < 2, typically approaching 1.75 due to contamination with Ag and oxides and carbon.[3]

For some time, it was doubted silver was actually in the +2 oxidation state rather in some combination of states such as AgI[AgIIIF4], which would be similar to silver(I,III) oxide. Neutron diffraction studies, however, confirmed its description as silver(II). The AgI[AgIIIF4] was found to be present at high temperatures, but it was unstable with respect to AgF2.[4]

In the gas phase, AgF2 is believed to have D∞h symmetry.

Approximately 14 kcal/mol (59 kJ/mol) separate the ground and first states. The compound is paramagnetic, but it becomes ferromagnetic at temperatures below −110 °C (163 K).

Uses

AgF2 is a strong fluorinating and oxidising agent. It is formed as an intermediate in the catalysis of gaseous reactions with fluorine by silver. With fluoride ions, it forms complex ions such as AgF−

3, the blue-violet AgF2−

4, and AgF4−

6.[5]

It is used in the fluorination and preparation of organic perfluorocompounds.[6] This type of reaction can occur in three different ways (here Z refers to any element or group attached to carbon, X is a halogen):

- CZ3H + 2 AgF2 → CZ3F +HF + 2 AgF

- CZ3X + 2AgF2 → CZ3F +X2 + 2 AgF

- Z2C=CZ2 + 2 AgF2 → Z2CFCFZ2 + 2 AgF

Similar transformations can also be effected using other high valence metallic fluorides such as CoF3, MnF3, CeF4, and PbF4.

AgF

2 is also used in the fluorination of aromatic compounds, although selective monofluorinations are more difficult:[7]

- C6H6 + 2 AgF2 → C6H5F + 2 AgF + HF

AgF

2 oxidises xenon to xenon difluoride in anhydrous HF solutions.[8]

- 2 AgF2 + Xe → 2 AgF + XeF2

It also oxidises carbon monoxide to carbonyl fluoride.

- 2 AgF2 + CO → 2 AgF + COF2

It reacts with water to form oxygen gas:[citation needed]

- 4 AgF2 + 4 H2O → 2 Ag2O + 8 HF + O2

Safety

AgF

2 is a very strong oxidizer that reacts violently with water,[9] reacts with dilute acids to produce ozone, oxidizes iodide to iodine,[9][10] and upon contact with acetylene forms the contact explosive silver acetylide.[11] It is light-sensitive,[9] very hygroscopic and corrosive. It decomposes violently on contact with hydrogen peroxide, releasing oxygen gas.[11] It also liberates HF, F

2, and elemental silver.[10]

References

- ^ Priest, H. F.; Swinehert, Carl F. (1950). "Anhydrous Metal Fluorides". Inorg. Synth. Inorganic Syntheses. 3: 171–183. doi:10.1002/9780470132340.ch47. ISBN 978-0-470-13234-0.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Kirk-Othermer. Vol.11, 4th Ed. (1991)

- ^ J.T. Wolan, G.B. Hoflund (1998). "Surface Characterization Study of AgF and AgF2 Powders Using XPS and ISS". Applied Surface Science. 125 (3–4): 251. doi:10.1016/S0169-4332(97)00498-4.

- ^ Hans-Christian Miller, Axel Schultz, and Magdolna Hargittai (2005). "Structure and Bonding in Silver Halides. A Quantum Chemical Study of the Monomers: Ag2X, AgX, AgX2, and AgX3(X = F, Cl, Br, I)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (22): 8133–45. doi:10.1021/ja051442j. PMID 15926841.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 83 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg; Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 1272–1273. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Rausch, D.; Davis, r.; Osborne, D. W. (1963). "The Addition of Fluorine to Halogenated Olefins by Means of Metal Fluorides". J. Org. Chem. 28 (2): 494–497. doi:10.1021/jo01037a055.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zweig, A.; Fischer, R. G.; Lancaster, J. (1980). "New Methods for Selective Monofluorination of Aromatics Using Silver Difluoride". J. Org. Chem. 45 (18): 3597. doi:10.1021/jo01306a011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levec, J.; Slivnik, J.; Zemva, B. (1974). "On the Reaction Between Xenon and Fluorine". Journal of Inorganic Nuclear Chemistry. 36 (5): 997. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(74)80203-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Dale L. Perry; Sidney L. Phillips (1995). Handbook of inorganic compounds. CRC Press. p. 352. ISBN 0-8493-8671-3.

- ^ a b W. L. F. Armarego; Christina Li Lin Chai (2009). Purification of Laboratory Chemicals (6th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 490. ISBN 1-85617-567-7.

- ^ a b Richard P. Pohanish; Stanley A. Greene (2009). Wiley Guide to Chemical Incompatibilities (3rd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 93. ISBN 0-470-38763-7.