New Netherland

New Netherland Nieuw-Nederland | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1614–1667 | |||||||||||

The coastline of New Netherland and some settlements shown relative to modern borders | |||||||||||

| Status | Dutch colony | ||||||||||

| Capital | New Amsterdam | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, English, French, and others [1][2] | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1614 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1667 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

New Netherland (Dutch: Nieuw-Nederland) was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod while the settled areas are now part of the Mid-Atlantic States of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut, with small outposts in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. The provincial capital of New Amsterdam was located at the southern tip of the island of Manhattan on upper New York Bay.

The colony was conceived as a private business venture to exploit the North American fur trade. During its first decades, New Netherland was settled rather slowly, partially as a result of policy mismanagement by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and partially as a result of conflicts with Native Americans. The settlement of New Sweden encroached on its southern flank, while its northern border was re-drawn to accommodate an expanding New England. During the 1650s, the colony experienced dramatic growth and became a major port for trade in the North Atlantic. The surrender of Fort Amsterdam to England in 1664 was formalized in 1667, contributing to the Second Anglo–Dutch War. In 1673, the Dutch re-took the area but relinquished it under the Second Treaty of Westminster ending the Third Anglo-Dutch War the next year.

The inhabitants of New Netherland were Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans, the latter chiefly imported as enslaved laborers. Descendants of the original settlers played a prominent role in colonial America. For two centuries, New Netherland Dutch culture characterized the region (today's Capital District around Albany, the Hudson Valley, western Long Island, northeastern New Jersey, and New York City). The concepts of civil liberties and pluralism introduced in the province became mainstays of American political and social life.

Origins

In the 17th-century, Europe was undergoing expansive social, cultural, and economic growth. In the Netherlands this is known as the Dutch Golden Age. Nations vied for domination of lucrative trade routes across the globe, particularly those to Asia.[3] Simultaneously, philosophical and theological conflicts were manifested in military battles across the continent. The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands had become a home to many intellectuals, international businessmen, and religious refugees. In the Americas, the English had a settlement at Jamestown, the French had a small settlements at Port Royal and Quebec, and the Spanish were developing colonies to exploit trade in South America and the Caribbean.[4]

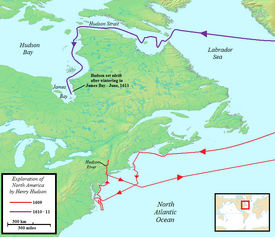

In 1609 Henry Hudson, an English sea captain and explorer, was hired by the Flemish Protestant emigres running the Dutch East India Company (VOC) located in Amsterdam,[5] to find a Northeast Passage to Asia sailing around Scandinavia and Russia. Turned back by the ice of the Arctic in his second attempt, he sailed west to seek a northwest passage rather than return home and ended up exploring the waters off the east coast of North America aboard the yacht Halve Maen. His first landfall was at Newfoundland and the second at Cape Cod. Believing the passage to the Pacific ocean was between the St. Lawrence River and Chesapeake Bay, Hudson sailed south to the Bay then turned northward, traveling close along the shore. He first discovered Delaware Bay and began to sail upriver looking for the passage. This effort was foiled by sandy shoals, and the Halve Maen continued north. After passing Sandy Hook, Hudson and his crew entered the narrows into the Upper New York Bay. (Unbeknownst to Hudson, the narrows had already been discovered in 1524 by explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano; today the bridge spanning them is named for him.[6]) Believing he may have found the continental water route, Hudson sailed up the major river which would later bear his name (the Hudson). Days later, at the site of present-day Albany, he found the water too shallow to proceed.[7]

Upon returning to the Netherlands, Hudson reported having found a fertile land and an amicable people willing to engage his crew in small-scale bartering of furs, trinkets, clothes, and small manufactured goods. His report, first published by the Antwerp emigre and Dutch Consul at London, Emanuel Van Meteren, in 1612,[5] stimulated interest[8] in exploiting this new trade resource, and was the catalyst for Dutch merchant-traders to fund more expeditions. Flemish Lutheran emigre merchants, such as Arnout Vogels, sent the first follow up voyages to exploit this discovery as early as July, 1610.[5]

In 1611–1612, the Admiralty of Amsterdam sent two covert expeditions to find a passage to China with the yachts Craen and Vos, captained by Jan Cornelisz Mey and Symon Willemsz Cat, respectively. In four voyages made between 1611 and 1614, the area between present-day Maryland and Massachusetts was explored, surveyed, and charted by Adriaen Block, Hendrick Christiaensen, and Cornelius Jacobsen Mey. The results of these explorations, surveys, and charts made from 1609 through 1614 were consolidated in Block’s map, which used the name New Netherland for the first time. On maps, it was also called Nova Belgica. During this period there was some trading with the native population. Dutch trader Jan Rodrigues (born in Santo Domingo of Portuguese and African descent) spent the winter of 1613–1614 trapping for pelts and trading with the local population. He was the first recorded non-Native American to do so.[9]

Development

Chartered trading companies

The immediate and intense competition between Dutch trading companies in the newly charted areas (especially in New York Bay and along the Hudson River) led to disputes and calls for regulation in Amsterdam. On March 17, 1614, the States General, the governing body of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, proclaimed it would grant an exclusive patent for trade between the 40th and 45th parallels. This monopoly would be valid for four voyages, all of which had to be undertaken within three years after it was awarded. Block's map, and the report which accompanied it, were used by the New Netherland Company (a newly formed alliance of trading companies) to win its patent, which would expire on January 1, 1618.[10]

The New Netherland Company also ordered a survey of the Delaware area. This was undertaken by skipper Cornelis Hendricksz of Monnickendam, who in 1616 explored the Zuyd Rivier (literally "South River," today known as the Delaware River) from its bay to its northernmost navigable reaches. His observations were preserved in a map drawn in 1616. Hendricksz's voyages were made aboard the IJseren Vercken (Iron Hog), a vessel built in America. Despite the survey, the company was unable to secure an exclusive patent from the States General for the area between the 38th and 40th parallels.[11]

The States General issued patents in 1614 for the development of New Netherland as a private, commercial venture. Soon thereafter traders built Fort Nassau on Castle Island in the area of present-day Albany up Hudson's river. The fort was to defend river traffic against interlopers and to conduct fur trading operations with the natives. The location of the fort proved to be impractical, due to repeated flooding of the island in the summers, and it was abandoned in 1618,[12] which coincided with the patent's expiration.

The Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compagnie, or Chartered West India Company (WIC), was granted a charter by the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on June 3, 1621.[13] It was given the exclusive right to operate in West Africa (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Cape of Good Hope) and the Americas.[13] In New Netherland, profit was originally to be made from the North American fur trade.

Among the founders of the WIC was Willem Usselincx. Between 1600 and 1606, he had promoted the concept that a main goal of the company should be establishing colonies in the New World. In 1620, Usselincx made a last appeal to the States General, which rejected his principal vision as a primary goal. The legislators preferred the formula of trading posts with small populations and a military presence to protect them, which was working in the East Indies, over encouraging mass immigration and establishing large colonies. Not until 1654, when forced to surrender Dutch Brazil and forfeit the richest sugar-producing area in the world, did the company belatedly focus on colonization in North America.

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

Pre-colonial population

The first trading partners of the New Netherlanders were the Algonquian who lived in the area.[14] The Dutch depended on the indigenous population to capture, skin and deliver pelts, especially beaver, to them. It is likely that Hudson's peaceful contact with the local Mahicans encouraged them to establish Fort Nassau in 1614, the first of many garrisoned trading stations to be built. In 1628, the Mohawks (members of the Iroquois Confederacy) conquered the Mahicans, who retreated to Connecticut. The Mohawks gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch, as they controlled the upstate Adirondacks and Mohawk Valley through the center of New York.[15]

The Algonquian Lenape population around New York Bay and along the Lower Hudson were seasonally migrational people. The Dutch called the numerous tribes collectively the River Indians.[15][16] known by their exonyms as the Wecquaesgeek, Hackensack, Raritan, Canarsee, Tappan. It was these groups who had most frequent contact with the New Netherlanders. The Munsee inhabited the Highlands, Hudson Valley, and northern New Jersey[15] while Minquas (called the Susquehannocks by the English) lived west of the Zuyd Rivier along and beyond the Susquehanna River that the Dutch regarded as their boundary with Virginia.

Company policy required land to be purchased from the indigenous peoples. The WIC would offer a land patent, the recipient of which would be responsible for negotiating a deal with representatives, usually the sachem, or high chief, of the local population. The Dutch (referred to by the natives as Swannekins, or salt water people) and the Wilden (as the Dutch called the natives) had vastly different conceptions of ownership and use of land, so much so that they did not understand each other at all.[15] The Dutch thought their proffer of gifts in the form of sewant or manufactured goods was a trade agreement and defense alliance, which gave them exclusive rights to farming, hunting, and fishing. Often, the Indians did not vacate the property, or reappeared seasonally, according to their migration patterns. They were willing to share the land with the Europeans, but the Indians did not intend to leave or give up access. This misunderstanding, and other differences, would later lead to violent conflict. At the same time, such differences marked the beginnings of a multicultural society.[17]

Early settlement

Like the French in the north, the first interest of the Dutch was the fur trade. To that end, they cultivated close relations with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, the access key to the central regions they from which the skins came.

Over time, to attract settlers to the region of the Hudson River, the Dutch encouraged a kind of feudal aristocracy in what became known as the system of the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions. Further south, a Swedish trading company that had ties with the Dutch tried to establish its first settlement along the Delaware River three years later. Without resources to consolidate its position, New Sweden was gradually absorbed by New Holland and later in Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The earliest Dutch settlement was built around 1613, and consisted of a number of small huts built by the crew of the "Tijger" (Tiger), a Dutch ship under the command of Captain Adriaen Block, which had caught fire while sailing on the Hudson.[18] Soon after, the first of two Fort Nassaus was built and small factorijen, or trading posts, where commerce could be conducted with Algonquian and Iroquois population, went up (possibly at Schenectady, Esopus, Quinnipiac, Communipaw and elsewhere).

In 1617 Dutch colonists built a fort at the confluence of the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, where Albany now stands. In 1624 New Netherland became a province of the Dutch Republic, which had lowered the northern border of its North American dominion to 42 degrees latitude in acknowledgment of the claim by the English north of Cape Cod.[nb 1] The Dutch named the three main rivers of the province the Zuyd Rivier (South River), the Noort Rivier (North River), and the Versche Rivier (Fresh River). Not only discovery and charting, but permanent settlement were needed to maintain a territorial claim. To this end, in May 1624, the WIC landed 30 families at Fort Orange and Noten Eylant (today's Governors Island) at the mouth of the North River. They disembarked from the ship New Netherland, under the command of Cornelis Jacobsz May, the first Director of the New Netherland. He was replaced the following year by Willem Verhulst.

In June 1625, 45 additional colonists disembarked on Noten Eylant from three ships named Horse, Cow, and Sheep, which also delivered 103 horses, steers, cows, pigs, and sheep. Some settlers were dispersed to the various garrisons built across the territory: upstream to Fort Orange, to Kievets Hoek on the Fresh River, and Fort Wilhelmus on the South River.[19][20] Many of the settlers were not Dutch, but Walloons, French Huguenots, or Africans (most as enslaved labor, some later gaining "half-free" status).[21][22]

North River and The Manhattans

Peter Minuit became Director of the New Netherland in 1626 and made a decision that would greatly affect the new colony. Originally, the capital of the province was to be located on the South River,[23] but it was soon realized that the location was susceptible to mosquito infestation in the summer and the freezing of its waterways in the winter. He chose instead the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the river explored by Hudson, at that time called the North River. In what is one of the most legendary real-estate deals ever made, Minuit traded some goods with the local population[24] and reported that he had purchased it from the natives, as was company policy. He ordered the construction of Fort Amsterdam at its southern tip, around which would grow the heart of the province, which, rather than New Netherland, would be called in the vernacular of the day The Manhattoes.[25][26] The port city outside the walls of the fort, New Amsterdam, would become a major hub for trade between North America, the Caribbean and Europe, and the place where raw materials such as pelts, lumber, and tobacco would be loaded. Sanctioned privateering would contribute to its growth. When given its municipal charter in 1653[27] the Commonality of New Amsterdam included the isle of Manhattan, Staaten Eylandt, Pavonia and the Lange Eylandt towns.[28]

In the hope of encouraging immigration, the Dutch West India Company, in 1629, established the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions, which gave it the power to offer vast land grants and the title of patroon to some of its invested members.[29] The vast tracts were called patroonships, and the title came with powerful manorial rights and privileges, such as the creation of civil and criminal courts and the appointing of local officials. In return, a patroon was required by the Company to establish a settlement of at least 50 families, who would live as tenant farmers, within four years. Of the original five patents given, the largest and only truly successful endeavour was Rensselaerswyck,[30] at the highest navigable point on the North River,[31] which became the main thoroughfare of the province. Beverwijck, grew from a trading post to a bustling, independent town in the midst of Rensselaerwyck, as would Wiltwyck, south of the patroonship in Esopus country.

Kieft's War and the Remonstrance of New Netherland

Willem Kieft was Director New Netherland from 1638 until 1647. Though the colony had grown somewhat before his arrival, it did not flourish, and Kieft was under pressure to cut costs. At this time a large number of Indian tribes who had signed mutual defense treaties with the Dutch were gathering near the colony due to widespread warfare and dislocation among the tribes to the north. At first he suggested collecting tribute from the Indians[32] (as was common among the various dominant tribes), but his demands to the Tappan and Wecquaesgeek were simply ignored. Subsequently, when a colonist was murdered in an act of revenge for some killings that had taken place years earlier and the Indians refused to turn over the perpetrator, Kieft suggested they be taught a lesson by ransacking their villages. In an attempt to gain public support he created a citizens commission, the Council of Twelve Men. They did not, as was expected, rubber-stamp his ideas, but took the opportunity to mention grievances that they had with company's mismanagement and its unresponsiveness to their suggestions. Kieft thanked and disbanded them, and against their advice ordered that groups of Tappan and Wecquaesgeek (who had sought refuge from their more powerful Mahican enemies, per their treaty understandings with the Dutch) be attacked at Pavonia and Corlear's Hook. The massacre left 130 dead. Within days the surrounding tribes, in a unique move, united and rampaged the countryside, forcing settlers who escaped to find safety at Fort Amsterdam. For two years, a series of raids and reprisals raged across the province, until 1645 when Kieft's War ended with a treaty, in a large part brokered by the Hackensack sagamore Oratam.[15] Disenchanted with the previous governor, his ignorance of indigenous peoples, the unresponsiveness of the WIC to their rights and requests, the colonists submitted to the States General the Remonstrance of New Netherland.[33] This document, penned by the Leiden-educated New Netherland lawyer Adriaen van der Donck, condemned the WIC for mismanagement and demanded full rights as citizens of province of the Netherlands.[17]

Director-General of New Netherland

Petrus Stuyvesant arrived in New Amsterdam in 1647, the only governor of the colony to be called Director-General. Some years earlier land ownership policy was liberalized and trading was somewhat deregulated, and many New Netherlanders considered themselves entrepreneurs in a free market.[17]

During the period of his governorship the province experienced exponential growth.[30] Demands were made upon Stuyvesant from all sides: the West India Company, the States General, and the New Netherlanders. Dutch territory was being nibbled at by the English to the north and the Swedes to the south, while in the heart of the province the Esopus were trying to contain further Dutch expansion. Discontent in New Amsterdam led locals to dispatch Adriaen van der Donck back to the United Provinces to seek redress. After nearly three years of legal and political wrangling, the Dutch Government came down against the WIC, granting the colony a measure of self-government and recalling Stuyvesant in April 1652. However, the orders were rescinded with the outbreak of the First Anglo-Dutch War a month later.[17] Military battles were occurring in the Caribbean and along the South Atlantic coast. In 1654, the Netherlands lost New Holland in Brazil to the Portuguese, encouraging some of its residents to emigrate north and making the North American colonies more appealing to some investors. The Esopus Wars are so named for the branch of Lenape that lived around Wiltwijck, which was the Dutch settlement on the west bank of Hudson River between Beverwyk and New Amsterdam. These conflicts were generally over settlement of land by New Netherlanders for which contracts had not been clarified, and were seen by the natives as an unwanted incursion into their territory. Previously, the Esopus, a clan of the Munsee Lenape, had much less contact with the River Indians and the Mohawks.[34]

Society

New Netherlanders were not necessarily Dutch, and New Netherland was never a homogeneous society.[2] An early governor, Pieter Minuit, was a German-born Walloon who spoke English and worked for a Dutch company.[35] The term New Netherland Dutch generally includes all the Europeans who came to live there,[1] but may also refer to Africans, Indo-Caribbeans, South Americans and even the Native Americans who were integral to the society. Though Dutch was the official language, and likely the lingua franca of the province, it was but one of many spoken there.[2] There were various Algonquian languages; Walloons and Huguenots tended to speak French, and Scandinavians brought their own tongues, as did the Germans. It is likely that the about 100 Africans (including both free men and slaves) on Manhattan spoke their mother tongues, but were taught Dutch from 1638 by Adam Roelantsz van Dokkum.[36] English was already on the rise to become the vehicular language in world trade, and settlement by individuals or groups of English-speakers started soon after the inception of the province. The arrival of refugees from New Holland in Brazil may have brought speakers of Portuguese, Spanish, and Ladino (with Hebrew as a liturgical language). Commercial activity in the harbor could have been transacted simultaneously in any of a number of tongues.[37]

The Dutch West India Company introduced slavery in 1625 with the importation of eleven black slaves who worked as farmers, fur traders, and builders. Although enslaved, the Africans had a few basic rights and families were usually kept intact. Admitted to the Dutch Reformed Church and married by its ministers, their children could be baptized. Slaves could testify in court, sign legal documents, and bring civil actions against whites. Some were permitted to work after hours earning wages equal to those paid to white workers. When the colony fell, the company freed all its slaves, establishing early on a nucleus of free negros.[38]

The Union of Utrecht, the founding document of the Dutch Republic, signed in 1579, stated "that everyone shall remain free in religion and that no one may be persecuted or investigated because of religion". The Dutch West India Company, however, established the Reformed Church as the official religious institution of New Netherland.[39] The colonists had to attract, "through attitude and by example", the natives and nonbelievers to God's word "without, on the other hand, to persecute someone by reason of his religion, and to leave everyone the freedom of his conscience." In addition, the laws and ordinances of the states of Holland were incorporated by reference in those first instructions to the Governors Island settlers in 1624. There were two test cases during Stuyvesant's governorship in which the rule prevailed: the official granting of full residency for both Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews in New Amsterdam in 1655, and the Flushing Remonstrance, involving Quakers, in 1657.[40][41] During the 1640s, two religious leaders, both women, took refuge in New Netherland: Anne Hutchinson and the Anabaptist Lady Deborah Moody.

Incursions

South River and New Sweden

Apart from the second Fort Nassau, and the small community that supported it, settlement along the Zuyd Rivier was limited. An attempt by patroons of Zwaanendael, Samuel Blommaert and Samuel Godijn was destroyed by the local population soon after its founding in 1631 during the absence of the their agent, David Pietersen de Vries.

Peter Minuit, who had construed a deed for Manhattan (and was soon after dismissed as director), knew that the Dutch would be unable to defend the southern flank of their North American territory and had not signed treaties with or purchased land from the Minquas. After gaining the support from the Queen of Sweden, he chose the southern banks of the Delaware Bay to establish a colony there, which he did in 1638, calling it Fort Christina, New Sweden. As expected, the government at New Amsterdam took no other action than to protest. Other settlements sprang up as colony grew, mostly populated by Swedes, Finns, Germans, and Dutch. In 1651, Fort Nassau was dismantled and relocated in an attempt to disrupt trade and reassert control, receiving the name Fort Casimir. Fort Beversreede was built in the same year, but was short-lived. In 1655, Stuyvesant led a military expedition and regained control of the region, calling its main town "New Amstel" (Nieuw-Amstel).[42] During this expedition, some villages and plantations at the Manhattans (Pavonia and Staten Island) were attacked in an incident that is known as the Peach Tree War.[17] These raids are sometimes considered revenge for the murder of an Indian girl attempting to pluck a peach, though it was likely that they were a retaliation for the attacks at New Sweden.[17][43] A new experimental settlement was begun in 1673, just before the British takeover in 1674. Franciscus van den Enden had drawn up charter for a utopian society that included equal education of all classes, joint ownership of property, and a democratically elected government.[17] Pieter Corneliszoon Plockhoy attempted such a settlement near the site of Zwaanendael, but it soon expired under English rule.[44]

Fresh River and New England

Few settlers to New Netherland made Fort Goede Hoop on the Fresh River their home. As early 1637 English settlers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony began to settle along its banks and on Lange Eylandt, some with the permission from the colonial government, and others with complete disregard for it. Developing simultaneously with that of New Netherland, the English colonies grew more rapidly since settlement by religious sects (rather than trade) was the impetus for their creation and growth. It was fear of an invasion by them that the wal, or rampart, at contemporary Wall Street was originally built. Initially there was limited contact between New Englanders and New Netherlanders, but with a swelling English population and territorial disputes the two provinces engaged in direct diplomatic relations. The New England Confederation was formed in 1643 as a political and military alliance of the English colonies of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven.[45] The latter two were actually on land claimed by the United Provinces, but the Dutch, unable to populate or militarily defend their territorial claim, could do nothing but protest the growing flood of English settlers. With the 1650 Treaty of Hartford, Stuyvesant provisionally ceded the Connecticut River region to New England, drawing New Netherland's eastern border 50 Dutch miles west of the Connecticut's mouth on the mainland and just west of Oyster Bay on Long Island. The Dutch West India Company refused to recognize the treaty, but since it failed to reach any agreement with the English, the Hartford Treaty set the de facto border. Although Connecticut mostly assimilated into New England the western part of the state maintains stronger ties with the Tri-State Region.

Capitulation, restitution, and concession

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

In March 1664, Charles II of England resolved to annex New Netherland and “bring all his Kingdoms under one form of government, both in church and state, and to install the Anglican government as in old England”. The directors of the Dutch West India Company concluded that the religious freedom of the colony made military defense against New England unnecessary. They wrote to Director-General Peter Stuyvesant:

. . . we are in hopes that as the English at the north (in New Netherland) have removed mostly from old England for the causes aforesaid, they will not give us henceforth so much trouble, but prefer to live free under us at peace with their consciences than to risk getting rid of our authority and then falling again under a government from which they had formerly fled.

On August 27, 1664, four English frigates, led by Richard Nicolls, sailed into New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded New Netherland’s surrender.[46] [47] They met no resistance because numerous citizens’ requests for protection by a suitable Dutch garrison against “the deplorable and tragic massacres” by the natives had gone unheeded. That lack of adequate fortification, ammunition, and manpower as well as the indifference from the West India Company to previous pleas for reinforcement of men and ships against “the continual troubles, threats, encroachments and invasions of the English neighbors” made New Amsterdam defenseless. Stuyvesant negotiated successfully for good terms from his “too powerful enemies.”[48] In the Articles of Transfer, he and his council secured the principle of religious tolerance in Article VIII, which assured that New Netherlanders “shall keep and enjoy the liberty of their consciences in religion” under English rule. Although largely observed in New Amsterdam and the Hudson River Valley, the Articles were immediately violated by the English along the Delaware River, where pillaging, looting, and arson were undertaken under the orders of English Colonel Richard Carr who had been dispatched to secure the valley. Many Dutch settlers were sold into slavery in Virginia on Carr's orders and an entire Mennonite settlement led by Pieter Corneliszoon Plockhoy near modern Lewes, Delaware was wiped out. In the 1667 Treaty of Breda ending the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch did not press their claims on New Netherland and the status quo, with the Dutch occupying Suriname and the nutmeg island of Run, was maintained.

Within six years the nations were again at war and in August 1673 the Dutch recaptured New Netherland with a fleet of 21 ships, then the largest ever seen in North America. They chose Anthony Colve as governor and renamed the city “New Orange”, reflecting the installation of William of Orange as Lord-Lieutenant (stadtholder) of Holland in 1672. (He would become King William III of England in 1689.) Nevertheless, after the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Dutch War in 1672–1674 — the historic “disaster years” in which the Dutch Republic was simultaneously attacked by the French under Louis XIV, the English, and the Bishops of Munster and Cologne — the republic was financially bankrupt. The States of Zeeland had tried to convince the States of Holland to take on the responsibility for the New Netherland province, but to no avail. In November 1674, the Treaty of Westminster concluded the war and ceded New Netherland to the English.[49]

Legacy

In addition to founding the largest metropolis on the North American continent, New Netherland has left a profoundly enduring legacy on both American cultural and political life, "a secular broadmindedness and mercantile pragmatism",[9] greatly influenced by social and political climate in the Dutch Republic at the time as well as by the character of those who immigrated to it.[50] It was during the early British colonial period that the New Netherlanders actually developed the land and society that would have an enduring impact on the Capital District, the Hudson Valley, North Jersey, western Long Island, New York City, and ultimately the United States.[9]

Political culture

Manifested, and occasionally embraced, as multiculturalism in late twentieth-century United States, the concept of tolerance was the mainstay of the province's mother country. The Dutch Republic was a haven for many religious and intellectual refugees fleeing oppression as well as home to the world's major ports in the newly developing global economy. Concepts of religious freedom and free-trade (including a stock market) were Netherlands imports. In 1682, the visiting Virginian William Byrd commented about New Amsterdam that "they have as many sects of religion there as at Amsterdam".

The Dutch Republic was one of the first nation-states of Europe where citizenship and civil liberties were extended to large segments of the population. The framers of the U.S. Constitution were influenced by the Constitution of the Republic of the United Provinces, though that influence was more as an example of things to avoid than of things to imitate.[51] In addition, the Act of Abjuration, essentially the declaration of independence of the United Provinces from the Spanish throne, is strikingly similar to the later American Declaration of Independence[52] though concrete evidence that the former directly influenced the latter is absent. John Adams went so far as to say that “the origins of the two Republics are so much alike that the history of one seems but a transcript from that of the other.”[53] The Articles of Capitulation (outlining the terms of transfer to the English) in 1664,[48] provided for the right to worship as one wished, and were incorporated into subsequent city, state, and national constitutions in the USA, and are the legal and cultural code that lies at the root of the New York Tri-State traditions.

Many prominent US citizens are Dutch American directly descended from the Dutch families of New Netherland.[54] The Roosevelt family, which produced two Presidents, are descended from Claes van Roosevelt, who emigrated around 1650.[55] The Van Buren family of President Martin Van Buren also originated in New Netherland.[3]

Lore

The colors of the flag of New York City, of Albany and of Nassau County are those of the old Dutch flag. The blue, white and orange are also seen in materials from New York's two World's Fairs and the uniforms of the New York Knicks basketball club, and New York Islanders hockey club. Hofstra University, founded in 1935, takes its flag from the original.

The seven arrows in the lion's left claw in the Republic's coat of arms, representing the seven provinces, was a precedent for the thirteen arrows in the eagle's left claw in the Great Seal of the United States.[56]

Any review of the legacy of New Netherland is complicated by the enormous impact of Washington Irving’s satirical A History of New York and its famous fictional author Diedrich Knickerbocker. Irving’s romantic vision of an enlightened, languid Dutch yeomanry dominated the popular imagination about the colony since its publication in 1809.[57] To this day, many mistakenly believe that Irving’s two most famous short stories "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" are based on actual folk tales of Dutch peasants in the Hudson Valley.[citation needed]

The tradition of Santa Claus is thought to have developed from a (gift-giving) celebration of the feast of Saint Nicholas on December 6 each year by the settlers of New Netherland.[17][58] The Dutch Sinterklaas was Americanized into "Santa Claus", a name first used in the American press in 1773,[59] when, in the early days of the revolt, Nicholas was used as a symbol of New York's non-British past.[58] However, many of the "traditions" of Santa Claus may have simply been invented by Irving in his 1809 Knickerbocker's History of New York from The Beginning of the World To the End of The Dutch Dynasty.[58]

Pinkster, the Dutch celebration of Spring is still celebrated in the Hudson Valley.

Language

Pidgin Delaware developed early in the province as a vehicular language to expedite trade. A dialect known as Jersey Dutch was spoken in and around rural Bergen and Passaic counties in New Jersey until the early 20th century.[60] Mohawk Dutch, spoken around Albany, is also now extinct.[61]

Many words of Dutch origin came into American vernacular directly from New Netherland.[62] For example, the quintessential American word Yankee may be a corruption of a Dutch name, Jan Kees. [nb 2][63] Knickerbocker, originally a surname, has been used to describe a number of things, including breeches, glasses, and a basketball team. Cookie is from the Dutch word koekje or (informally) koekie. Boss, from baas, evolved in New Netherland to the usage known today. [nb 3]

Placenames

Early settlers and their descendents gave many placenames still in use throughout the region that was New Netherland.[3] Using Dutch, and the Latin alphabet, they also "Batavianized"[17] names of Native American geographical locations such as Manhattan, Hackensack, Sing-Sing, and Canarsie. Peekskill, Catskill, and Cresskill all refer to the streams, or kils, around which they grew. Schuylkill River is somewhat redundant, since kil is already built into it. Among those that use hoek, meaning corner,[64] are: Red Hook, Sandy Hook, Constable Hook, and Kinderhook. Nearly pure Dutch forms name the bodies of water Spuyten Duyvil, Kill van Kull, and Hell Gate. Countless towns, streets, and parks bear names derived from Dutch places or from the surnames of the early Dutch settlers. Hudson and the House of Orange-Nassau lend their names to numerous places in the Northeast.

See also

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

- New Holland (Acadia)

- New Netherland 1614-1667 - Documentery

- New Netherland Project to translate and publish 17th century Dutch documents about the colony

- Congregation Shearith Israel, Jewish temple founded in the colony in 1655

- Dutch Occupation of Acadia, military action in Maine and New Brunswick in 1674

- Dutch American, an inhabitant of the United States of whole or partial Dutch ancestry

- Dutch Colonial, an architectural revival movement

- Holland Society of New York

- List of English words of Dutch origin

- List of place names of Dutch origin

References

- Explanatory notes

- ^ see John Smith's 1616 map as self-appointed Admiral of New England

- ^ Yankee : from Jan Kees, a personal name, originally used mockingly to describe pro-French revolutionary citizens, with allusion to the small keeshond dog, then for "colonials" in New Amsterdam. The Oxford English Dictionary, however, has quotations with the term from as early as 1765, quite some time before the French Revolution.

- ^ From Dutch baas, a term of respect originally used to address an older relative. Later, in New Amsterdam, it came to mean a person in charge who was not a master.

- Citations

- ^ a b "The New Netherland Dutch". The People of Colonial Albany live here. 2003-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Shorto, Russell (2003-11-27). "The Un-Pilgrims — The New York Times". The New York Times (New York edition ed.). p. 39. ISSN 0362–4331. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

{{cite news}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|issn=value (help) - ^ a b c "The Dutch in America, 1609–1664" (The Library of Congress Global Gateway). The Atlantic World (in English/Dutch).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Sandler, Corey (2007). Henry Hudson Dreams and Obsession. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0=8065-2739-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c "The Flemish Influence On Henry Hudson". The Brussels Journal. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ Wroth, Lawrence (1970). The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1524–1528. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01207-1.

- ^ Nieuwe Wereldt ofte Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien, uit veelerhande Schriften ende Aen-teekeningen van verscheyden Natien (Leiden, Bonaventure & Abraham Elseviers, 1625)p.84:"/tot by de 43 graden by noorden de linie/ alwaer de rivier heel nauw werdt ende ondiep/ soo dat sy terugghe keerden."("upto 43 degrees north by the line/ where the river got very narrow and shallow/ upon which they returned")

- ^ Nieuwe Wereldt ofte Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien, uit veelerhande Schriften ende Aen-teekeningen van verscheyden Natien (Leiden, Bonaventure & Abraham Elseviers, 1625) p.84: "Hendrick Hudson met dit raport wederghekeert zijnde 't Amsterdam/ zoo hebben eenighe koop-lieden in den jare 1610 weder een schip derwaerts gezonden/ te weten naer deze tweede rivier/ de welcke zij den naem gaven van Manhattes" ("As soon as Hudson returned with his report to Amsterdam, merchants sent another ship in 1610 specifically to this second river, to which they gave the name Manhattes")

- ^ a b c Paumgarten, Nick (2009-08-31). "Useless Beauty - What is to be done with Governors Island?". The New Yorker (LXXXV, No 26 ed.). p. 56. ISSN 00028792X.

{{cite news}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ "Grant of Exclusive Trade to New Netherland by the States-General of the United Netherlands; October 11, 1614". 2008.

- ^ Jaap Jacobs (2005), New Netherland: A Dutch Colony In Seventeenth-Century America. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12906-5, p. 35.

- ^ "A Virtual Tour of New Netherland: Fort Nassau". The New Netherland Institute. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ a b Charter of the Dutch West India Company : 1621, 2008

- ^ http://www.lowensteyn.com/iroquois/

- ^ a b c d e Ruttenber, E.M. (2001). Indian Tribes of Hudson's River (3rd ed.). Hope Farm Press. ISBN 0-910746-98-2. Cite error: The named reference "ruttenber910746" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Dutch Colonization". Kingston: A national register of historic places travel itinerary.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shorto, Russell (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-7867-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Welling, George M. (2004-11-24). "The United States of America and the Netherlands: The First Dutch Settlers". From Revolution to Reconstruction.

- ^ Bert van Steeg. "Walen in de Wildernis". De wereld van Peter Stuyvesant (in Dutch).

- ^ "1624 In the Unity (Eendracht)". Rootsweb Ancestry.com.

- ^ Slavery in New York

- ^ "Slavery in New Netherland / De slavernij in Nieuw Nederland" (The Library of Congress Global Gateway). The Atlantic World / De Atlantische Wereld (in English/Dutch).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Rink, Oliver (2009). "Seafarers ad Businessmen:". Dutch New York:The Roots of Hudson Valley Culture. Yonkers, NY: Fordham University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8232-3039-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|co-publisher=ignored (help) - ^ "New York: History — Islands Draw Native American, Dutch, and English Settlement". city-data.com.

- ^ van Rensselaer (1909). The History of the city of New York. Vol. 1. New York: Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Paul Gibson Burton (1937). The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. The New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. p. 6.Cornelis Meyln: "I was obliged to flee for the sake of saving my life, and to sojourn with wife and children at the Menatans till the year 1647."

- ^ http://www.council.nyc.gov/html/about/history.shtml

- ^ Map of Long Island Townshttp://www.bklyn-genealogy-info.com/Town/OldBklyn.html

- ^ Johan van Hartskamp. "De West-Indische Compagnie En Haar Belangen in Nieuw-Nederland Een Overzicht (1621–1664)". De wereld van Peter Stuyvesant.

- ^ a b Welling, George M. (2003-03-06). "The United States of America and the Netherlands: Nieuw Nederland — New Netherland". From Revolution to Reconstruction.

- ^ "The Patroon System / Het systeem van patroonschappen" (The Library of Congress Global Gateway). The Atlantic World / De Atlantische Wereld. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ Jacobs, Jaap (2005). New Netherland: A Dutch Colony In Seventeenth-Century America. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12906-5.

Both in the way it was set up and in the extent of its rights, the council of Twelve Men, as did the two later advisory bodies ...

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ de Koning, Joep M.J. (2000-08). "From Van der Donck to Visscher: A 1648 View of New Amsterdam". Mercator’s World. Vol. 5, no. 4. pp. 28–33. ISSN 1086-6728. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Otto, Paul (2006). The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-672-0.

- ^ Goodwin, Maud Wilder (1919). "Patroons and Lords of the Manor". In Allen Johnson (ed.). Dutch and English on the Hudson. The Chronicles of America. Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacobs, J. (2005) New Netherland: a Dutch colony in seventeenth-century America, p. 313. [1]

- ^ "A Brief Outline of the History of New Netherland". New Netherland History. 2003-02. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hodges, Russel Graham (1999). "Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863" (Document). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Wentz, Abel Ross (1955). "New Netherland and New York". A Basic History of Lutheranism in America. Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press. p. 6.

- ^ Glenn Collins (2007-12-05). "Precursor of the Constitution Goes on Display in Queens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^

Michael Peabody (November/December 2005). "The Flushing Remonstrance". Liberty Magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ *Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin.

- ^

Trelease, Allen, Starna, William (1997-06). Indian Affairs in Colonial New York: The Seventeenth Century. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Plantenga, Bart (2001-04). "The Mystery of the Plockhoy Settlement in the Valley of Swans". Historical Committee & Archives of the Mennonite Church: Mennonite Historical Bulletin.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Welling, George M. (2006-05-25). "New England Articles of Confederation (1643)". From Revolution to Reconstruction. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ "Articles about the Transfer of New Netherland on the 27th of August, Old Style, Anno 1664". World Digital Library. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Versteer (editor), Dingman (April and May 1911). "New Amsterdam Becomes New York". 1 (4 & 5). New Netherland Register: 49–64.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Articles of Capitulation on the Reduction of New Netherland". New Netherland Museum and the Half Moon.

- ^ Westdorp, Martina. "Behouden of opgeven ? Het lot van de nederlandse kolonie Nieuw-Nederland na de herovering op de Engelsen in 1673". De wereld van Peter Stuyvesant (in Dutch). Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^

Roberts, Sam (January 24, 2009). "Henry Hudson's View of New York: When Trees Tipped the Sky". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Alexander Hamilton, James Madison (1787-12-11). Federalist Papers no. 20. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ Barbara Wolff (1998-06-29). "Was Declaration of Independence inspired by Dutch?". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ^ Reagan, Ronald (1982-04-19). "Remarks at the Welcoming Ceremony for Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands". Public Papers of Ronald Reagan. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ *Welling, George M. (2003-03-06). "The United States of America and the Netherlands:". From Revolution to Reconstruction.

- ^ "Oud Vossemeer — The cradle of the U.S.A. Roosevelt presidents and family". Retrieved 2008-02-28. [dead link]

- ^ Velde, François (2003-12-08). "Official Heraldry of the United States".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Bradley, Elizabeth L. (2009). “Kinkerbocker: The Myth Behind New York”. Rutgers University Press.

- ^ a b c Jona Lendering (2008-11-20). "Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Santa Claus: New York 1776". livius.org.

- ^ "Last Monday, the anniversary of St. Nicholas, otherwise called Santa Claus, was celebrated at Protestant Hall, at Mr. Waldron’s; where a great number of sons of the ancient saint, the "Sons of Saint Nicholas", celebrated the day with great joy and festivity." Rivington’s Gazette (New York City), December 23, 1773.

- ^ Mencken, H.L. (2000) [1921]. "Dutch". The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States (2nd revised and enlarged ed.). New York: bartleby.com.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Pearson, Jonathan (1883). A History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times. Original from Harvard University, Digitized May 10, 2007. Schenectady (N.Y.): Munsell's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Van defr Sijs, Nicoline (2009), Cookies, Coleslaw and Stoops, University of Amsterdam Press, ISBN 9789089641243

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. 2001-11. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Voorhees, David William (2009). "The Dutch Legacy in America". Dutch New York:The Roots of Hudson Valley Culture. Yonkers, NY: Fordham University Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-8232-3039-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|co-publisher=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. New York City 1664–1710. Conquest and Change (1976).

- Bachman, V.C. Peltries or Plantations. The Economic Policies of the Dutch West India Company in New Netherland 1633–1639 (1969).

- Balmer, Randall H. "The Social Roots of Dutch Pietism in the Middle Colonies," Church History Volume: 53. Issue: 2. 1984. pp 187+ online edition

- Barnouw, A.J. "The Settlement of New Netherland," in A.C. Flick ed., History of the State of New York (10 vols., New York 1933), 1:215–258.

- Burrows, Edward G. and Michael Wallace. Gotham. A History of New York City to 1898 (1999).

- Condon, Thomas J. New York Beginnings. The Commercial Origins of New Netherland (1968).

- Jacobs, Jaap. The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (2nd ed. Cornell U.P. 2009) 320pp; scholarly history to 1674 online 1st edition

- McKinley, Albert E. The English and Dutch Towns of New Netherland.” American Historical Review (1900) 6#1 pp 1-18 in JSTOR

- McKinley, Albert E. “The Transition from Dutch to English Rule in New York: A Study in Political Imitation.” American Historical Review (1901) 6#4 pp: 693-724. in JSTOR

- Merwick, Donna. The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New Netherland (2006) 332 pages

- Rink, Oliver A. Holland on the Hudson. An Economic and Social History of Dutch New York (Cornell University Press, 1986)

- Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.), Exploring Historic Dutch New York. Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, New York (2011). ISBN 978-0-486-48637-6

- Schmidt, Benjamin, Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570-1670, Cambridge: University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-521-80408-0

- Venema, Janny, "Beverwijck: a Dutch village on the American frontier, 1652-1664.," Albany : State University of New York Press, 2003.

- Venema, Janny, "Kiliaen van Rensselaer (1586-1643) : designing a new world," Albany : State University of New York Press, 2010.

Primary sources

- Narratives of New Netherland, 1609–1664 (1909), edited by J.F. Jameson, at the Project Gutenberg

- Van Der Donck, Adriaen. A Description of New Netherland (1655; new ed. 2008) 208 pp. ISBN 978-0-8032-1088-2.

- Bayrd Still, ed. Mirror for Gotham: New York as Seen by Contemporaries from Dutch Days to the Present (1956)

- Several primary sources (both translated and in the original Dutch) can be found at the website of the New Netherland Institute. Also included on the NNI site is is a comprehensive list of scholarly, nonfiction publications broadly related to the seventeenth-century Dutch colony and its legacy in America.

External links

- The Mannahatta Project

- Slavery in New York

- 2009 Pinkster celebrations

- The New Netherland Museum and the Half Moon

- The New Netherland Institute

- Dutch Portuguese Colonial History

- New Netherland and Beyond

- A Brief Outline of the History of New Netherland at the University of Notre Dame

- AWAD: The Atlantic World and the Dutch, 1500–2000

- Old New York: Hear Dutch names of New York

- New Netherland

- Colonial United States (Dutch)

- Colonization history of the United States

- Colonization of the Americas

- States and territories established in 1609

- 1614 establishments

- 1674 disestablishments

- Colonial settlements in North America

- History of the Netherlands

- History of the Thirteen Colonies

- Former Dutch colonies

- Former English colonies

- Populated places established in the 17th century

- World Digital Library related